CULT (ISS Experiment) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cult'' is a term, sometimes considered pejorative, for a relatively small group which is typically led by a

Sects and Cults

" Greenville Technical College. Retrieved 21 March 2013. Other researchers present a less-organized picture of cults, saying that they arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices. Groups labelled as "cults" range in size from local groups with a few members to international organizations with millions.

Defining Religion in American Law

(lecture). ''Conference On The Controversy Concerning Sects In French-Speaking Europe''. Sponsored by CESNUR and CLIMS. Archived from th

original

on 10 November 2005.

A ''new religious movement'' (NRM) is a religious community or spiritual group of modern origins (since the mid-1800s), which has a peripheral place within its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct from pre-existing denominations.Clarke, Peter B. 2006. ''New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World''. New York: Routledge. Siegler, Elijah. 2007. ''New Religious Movements''.

A ''new religious movement'' (NRM) is a religious community or spiritual group of modern origins (since the mid-1800s), which has a peripheral place within its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct from pre-existing denominations.Clarke, Peter B. 2006. ''New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World''. New York: Routledge. Siegler, Elijah. 2007. ''New Religious Movements''.

Sociologist

Sociologist

Stressed to Kill: The Defense of Brainwashing; Sniper Suspect's Claim Triggers More Debate

" ''Defence Brief'' 269. Toronto: Steven Skurka & Associates. Archived from th

on 1 May 2011. has defended some so-called cults, and in 1988 argued that involvement in such movements may often have beneficial, rather than harmful effects, saying that " ere's a large

Ten Years After Jonestown, the Battle Intensifies Over the Influence of 'Alternative' Religions

" '' Los Angeles Times.'' In their 1996 book ''Theory of Religion'', American sociologists Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge propose that the formation of cults can be explained through the

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action and

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action and

The Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult

" Retrieved 6 June 2020. Revised editions: '' Liberty'' magazine (1987), and Center for Libertarian Studies (1990). The core group around Rand was called the "Collective", which are now defunct; the chief group which is disseminating Rand's ideas today is the Ayn Rand Institute. Although the Collective advocated an individualist philosophy, Rothbard claimed that it was organized in the manner of a " Leninist" organization.

Give and Forget

/ref>

'' The New York Times'', 21 January 1992 In 1977, the

Sara Diamond, 1989, Pluto Press, Page 58 The committee also investigated possible KCIA influence on the Unification Church's campaign in support of Nixon. In 1980, members founded CAUSA International, an

''

'' The Washington Post'', 1984-09-17. "Another church political arm, Causa International, which preaches a philosophy it calls "God-ism," has been spending millions of dollars on expense-paid seminars and conferences for Senate staffers, Hispanic Americans and conservative activists. It also has contributed $500,000 to finance an anticommunist lobbying campaign headed by John T. (Terry) Dolan, chairman of the National Conservative Political Action Committee (NCPAC)." In 1986, CAUSA International sponsored the documentary film ''

'' The Washington Post'', 1984-09-17. In the same year, member

// Goliath Business News In April 1990, Moon visited the Soviet Union and met with President

from '' The New York Times'' In 1994, '' The New York Times'' recognized the movement's political influence, saying it was "a theocratic powerhouse that is pouring foreign fortunes into conservative causes in the United States." In 1998, the Egyptian newspaper ''

Aram Roston, '' The Daily Beast'', February 7, 2012 Joo was born in North Korea and is a citizen of the United States.Unification Church president on condolence visit to N. Korea

'' Yonhap News'', December 26, 2011 The Unification Church also owns several news outlets including '' The Washington Times'', '' Insight on the News'', United Press International and the News World Communications network.As U.S. Media Ownership Shrinks, Who Covers Islam?

'' Washington Report on Middle East Affairs'', December 1997 ''Washington Times''

'Cults, Sects and the Far Left'

(review). ''What Next?'' 17. .

Sociologist and historian

Sociologist and historian

p. 8

Martin examines a large number of new religious movements; included are major groups such as

In the early 1970s, a secular opposition movement to groups considered cults had taken shape. The organizations that formed the secular anti-cult movement (ACM) often acted on behalf of relatives of "cult"

In the early 1970s, a secular opposition movement to groups considered cults had taken shape. The organizations that formed the secular anti-cult movement (ACM) often acted on behalf of relatives of "cult"

Sekten und Psychogruppen – Leitstelle Berlin

While the official response to new religious groups has been mixed across the globe, some governments aligned more with the critics of these groups to the extent of distinguishing between "legitimate" religion and "dangerous", "unwanted" cults in public policy.

For centuries, governments in China have categorized certain religions as '' xiéjiào'' (), sometimes translated as "evil cults" or " heterodox teachings". In

For centuries, governments in China have categorized certain religions as '' xiéjiào'' (), sometimes translated as "evil cults" or " heterodox teachings". In

United States v. Fishman

', 743 F. Supp. 713 ( N.D. Cal. 1990). In the case's ruling, the court cited the Frye standard, which states that the

Full text online

* Esquerre, Arnaud: ''La manipulation mentale. Sociologie des sectes en France'', Fayard, Paris, 2009. * House, Wayne: ''Charts of Cults, Sects, and Religious Movements'', 2000, * Kramer, Joel and Alstad, Diane: ''The Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power'', 1993. * Lalich, Janja: ''Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults'', 2004, * Landau Tobias, Madeleine et al. : ''Captive Hearts, Captive Minds'', 1994, * Lewis, James R. ''Odd Gods: New Religions and the Cult Controversy'', Prometheus Books, 2001 * Martin, Walter et al.: ''

Questions and Answers

* Lifton, Robert Jay

"Cult Formation"

''The Harvard Mental Health Letter'', February 1991 * Robbins, T. and D. Anthony, 1982. "Deprogramming, brainwashing and the medicalization of deviant religious groups" ''Social Problems'' 29 pp. 283–297. * Rosedale, Herbert et al.

* Van Hoey, Sara

''The Los Angeles Lawyer'', February 1991 * Zimbardo, Philip

"What messages are behind today's cults?"

''American Psychological Association Monitor'', May 1997

charismatic

Charisma () is a personal quality of presence or charm that compels its subjects.

Scholars in sociology, political science, psychology, and management reserve the term for a type of leadership seen as extraordinary; in these fields, the term "ch ...

and self-appointed leader, who excessively controls its members, requiring unwavering devotion to a set of beliefs and practices which are considered deviant (outside the norms of society). This term is also used for a new religious movement or other social group which is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally com ...

in a particular personality, object, or goal. This sense of the term is weakly definedhaving divergent definitions both in popular culture and academiaand has also been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across several fields of study. Richardson, James T. 1993. "Definitions of Cult: From Sociological-Technical to Popular-Negative." ''Review of Religious Research

The ''Review of Religious Research'' is a quarterly journal that reviews the various methods, findings and uses of religious research. It contains a variety of articles, book reviews and reports on research projects. It is published by the Reli ...

'' 34(4):348–356. . .

An older sense of the word involves a set of religious devotional practices that is conventional within its culture, is related to a particular figure, and is frequently associated with a particular place. References to the imperial cult of ancient Rome, for example, use the word in this sense. A derived sense of "excessive devotion" arose in the 19th century.Compare the '' Oxford English Dictionary'' note for usage in 1875: "cult:…b. A relatively small group of people having (esp. religious) beliefs or practices regarded by others as strange or sinister, or as exercising excessive control over members.… 1875 ''Brit. Mail 30'' Jan. 13/1 Buffaloism is, it would seem, a cult, a creed, a secret community, the members of which are bound together by strange and weird vows, and listen in hidden conclave to mysterious lore."

Beginning in the 1930s, cults became an object of sociological study within the context of the study of religious behavior. Since the 1940s, the Christian countercult movement has opposed some sects and new religious movements, labeling them "cults" because of their unorthodox beliefs. Since the 1970s, the secular anti-cult movement has opposed certain groups and, as a reaction to acts of violence, frequently charged those cults with practicing mind control. Scholars and the media have disputed some of the claims and actions of anti-cult movements, leading to further public controversy.

Sociological classifications of religious movements may identify a cult as a social group with socially deviant or novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

beliefs and practices, although this is often unclear.Shaw, Chuck. 2005.Sects and Cults

" Greenville Technical College. Retrieved 21 March 2013. Other researchers present a less-organized picture of cults, saying that they arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices. Groups labelled as "cults" range in size from local groups with a few members to international organizations with millions.

Usage of the term 'cult'

In the English-speaking world, the term ''cult'' often carries derogatory connotations. In this sense, it has been considered asubjective

Subjective may refer to:

* Subjectivity, a subject's personal perspective, feelings, beliefs, desires or discovery, as opposed to those made from an independent, objective, point of view

** Subjective experience, the subjective quality of conscio ...

term, used as an ''ad hominem

''Ad hominem'' (), short for ''argumentum ad hominem'' (), refers to several types of arguments, most of which are fallacious.

Typically, this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some other ...

'' attack against groups with differing doctrines or practices. As such, religion scholar Megan Goodwin has defined the term ''cult'', when it is used by the layperson, as often being shorthand for a "religion I don't like".

In the 1970s, with the rise of secular anti-cult movements, scholars (though not the general public) began to abandon the use of the term ''cult''. According to ''The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements'', "by the end of the decade, the term 'new religions' would virtually replace the term 'cult' to describe all of those leftover groups that did not fit easily under the label of church or sect."

Sociologist Amy Ryan (2000) has argued for the need to differentiate those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign. Ryan notes the sharp differences between definitions offered by cult opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and those offered by sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. The movements themselves may have different definitions of religion as well. George Chryssides also cites a need to develop better definitions to allow for common ground in the debate. Casino (1999) presents the issue as crucial to international human rights laws. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with freedom of religion, while too broad a definition may give some dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all unwanted legal obligations."Casino. Bruce J. 15 March 1999.Defining Religion in American Law

(lecture). ''Conference On The Controversy Concerning Sects In French-Speaking Europe''. Sponsored by CESNUR and CLIMS. Archived from th

original

on 10 November 2005.

New religious movements

Prentice Hall

Prentice Hall was an American major educational publisher owned by Savvas Learning Company. Prentice Hall publishes print and digital content for the 6–12 and higher-education market, and distributes its technical titles through the Safari B ...

. . In 1999, Eileen Barker estimated that NRMs, of which some but not all have been labelled as cults, number in the tens of thousands worldwide, most of which originated in Asia or Africa; and that the great majority of which have only a few members, some have thousands and only very few have more than a million. Barker, Eileen. 1999. "New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance." ''New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response'', edited by B. Wilson and J. Cresswell. Routledge. . In 2007, religious scholar Elijah Siegler

Elijah Siegler is the chair of the Religious Studies department at the College of Charleston

The College of Charleston (CofC or Charleston) is a public university in Charleston, South Carolina. Founded in 1770 and chartered in 1785, it is the ...

commented that, although no NRM had become the dominant faith in any country, many of the concepts which they had first introduced (often referred to as " New Age" ideas) have become part of worldwide mainstream culture.

Scholarly studies

Sociologist

Sociologist Max Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas profo ...

(1864–1920) found that cults based on charismatic leadership often follow the routinization of charisma

Charismatic authority is a concept of leadership developed by the German Sociology, sociologist Max Weber. It involves a type of organization or a type of leadership in which authority derives from the charisma of the leader. This stands in contras ...

.

The concept of a ''cult'' as a sociological classification, however, was introduced in 1932 by American sociologist Howard P. Becker

Howard Paul Becker (December 9, 1899 – June 8, 1960) was a longtime professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Biography

Becker was born in New York in 1899, the son of Charles Becker, a New York police officer, and Let ...

as an expansion of German theologian Ernst Troeltsch's '' church–sect typology''. Troeltsch's aim was to distinguish between three main types of religious behaviour: churchly, sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

, and mystical.

Becker further bisected Troeltsch's first two categories: ''church'' was split into ''ecclesia'' and ''denomination''; and ''sect'' into '' sect'' and ''cult''. Like Troeltsch's "mystical religion", Becker's ''cult'' refers to small religious groups that lack in organization and emphasize the private nature of personal beliefs. Later sociological formulations built on such characteristics, placing an additional emphasis on cults as deviant religious groups, "deriving their inspiration from outside of the predominant religious culture." This is often thought to lead to a high degree of tension between the group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it, a characteristic shared with religious sects. According to this sociological terminology, ''sects'' are products of religious schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

and therefore maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices, whereas ''cults'' arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.

In the early 1960s, sociologist John Lofland, living with South Korean missionary Young Oon Kim

Young Oon Kim (1914–1989) was a leading theologian of the Unification Church and its first missionary to the United States.J. Isamu Yamamoto, 1994, ''Unification Church: Zondervan guide to cults & religious movements'', Zondervan, pages 8 and ...

and some of the first American Unification Church members in California, studied their activities in trying to promote their beliefs and win new members. Lofland noted that most of their efforts were ineffective and that most of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with other members, often family relationships. Lofland published his findings in 1964 as a doctoral thesis entitled "The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes", and in 1966 in book form by Prentice-Hall

Prentice Hall was an American major educational publisher owned by Savvas Learning Company. Prentice Hall publishes print and digital content for the 6–12 and higher-education market, and distributes its technical titles through the Safari B ...

as '' Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization and Maintenance of Faith''. It is considered to be one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion.

Sociologist Roy Wallis

Roy Wallis (1945–1990) was a sociologist and Dean of the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences at the Queen's University Belfast. He is mostly known for his creation of the seven signs that differentiate a religious congregation from a sect ...

(1945–1990) argued that a cult is characterized by "epistemological

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

individualism," meaning that "the cult has no clear locus of final authority beyond the individual member." Cults, according to Wallis, are generally described as "oriented towards the problems of individuals, loosely structured, tolerant ndnon-exclusive," making "few demands on members," without possessing a "clear distinction between members and non-members," having "a rapid turnover of membership" and as being transient collectives with vague boundaries and fluctuating belief systems. Wallis asserts that cults emerge from the "cultic milieu".

J. Gordon Melton

John Gordon Melton (born September 19, 1942) is an American religious scholar who was the founding director of the Institute for the Study of American Religion and is currently the Distinguished Professor of American Religious History with the Ins ...

stated that, in 1970, "one could count the number of active researchers on new religions on one's hands." However, James R. Lewis writes that the "meteoric growth" in this field of study can be attributed to the cult controversy of the early 1970s. Because of "a wave of nontraditional religiosity" in the late 1960s and early 1970s, academics perceived new religious movements as different phenomena from previous religious innovations.

In 1978, Bruce Campbell noted that cults are associated with beliefs in a divine element in the individual

An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own Maslow ...

; it is either '' soul'', '' self'', or ''true self''. Cults are inherently ephemeral and loosely organized. There is a major theme in many of the recent works that show the relationship between cults and mysticism. Campbell, describing ''cults'' as non-traditional religious groups based on belief in a divine element in the individual, brings two major types of such to attentionmystical and instrumentaldividing cults into either occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

or metaphysical assembly. There is also a third type, the service-oriented, as Campbell states that "the kinds of stable forms which evolve in the development of religious organization will bear a significant relationship to the content of the religious experience of the founder or founders."Campbell, Bruce. 1978. "A Typology of Cults." ''Sociology Analysis''. Santa Barbara.

Dick Anthony

Dick Anthony is a forensic psychologist noted for his writings on the validity of brainwashing as a determiner of behavior, a prolific researcher of the social and psychological aspects of involvement in new religious movements.

Academic career

...

, a forensic psychologist known for his criticism of brainwashing

Brainwashing (also known as mind control, menticide, coercive persuasion, thought control, thought reform, and forced re-education) is the concept that the human mind can be altered or controlled by certain psychological techniques. Brainwash ...

theory of conversion,Oldenburg, Don. 0032003.Stressed to Kill: The Defense of Brainwashing; Sniper Suspect's Claim Triggers More Debate

" ''Defence Brief'' 269. Toronto: Steven Skurka & Associates. Archived from th

on 1 May 2011. has defended some so-called cults, and in 1988 argued that involvement in such movements may often have beneficial, rather than harmful effects, saying that " ere's a large

research literature

: ''For a broader class of literature, see Academic publishing.''

Scientific literature comprises scholarly publications that report original Empirical evidence, empirical and theoretical work in the natural science, natural and social science ...

published in mainstream journals on the mental health effects of new religions. For the most part, the effects seem to be positive in any way that's measurable." Sipchen, Bob. 17 November 1988.Ten Years After Jonestown, the Battle Intensifies Over the Influence of 'Alternative' Religions

" '' Los Angeles Times.'' In their 1996 book ''Theory of Religion'', American sociologists Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge propose that the formation of cults can be explained through the

rational choice theory

Rational choice theory refers to a set of guidelines that help understand economic and social behaviour. The theory originated in the eighteenth century and can be traced back to political economist and philosopher, Adam Smith. The theory postula ...

. In ''The Future of Religion'' they comment that, "in the beginning, all religions are obscure, tiny, deviant cult movements." According to Marc Galanter, Professor of Psychiatry at NYU, typical reasons why people join cults include a search for community and a spiritual quest. Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which individuals join new religious groups, have even questioned the utility of the concept of '' conversion'', suggesting that '' affiliation'' is a more useful concept.

Subcategories

Destructive cults

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."

''Destructive cult'' generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public." Psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and interpretation of how indi ...

Michael Langone, executive director of the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association, defines a destructive cult as "a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits."

John Gordon Clark

John 'Jack' Gordon Clark (1926–1999) was a Harvard psychiatrist known for his research on the alleged damaging effects of cults.

He was the target of harassment from the Church of Scientology after he testified against it to the Vermont ...

argued that totalitarian systems of governance and an emphasis on money making are characteristics of a destructive cult. In ''Cults and the Family'', the authors cite Shapiro, who defines a ''destructive cultism'' as a sociopathic syndrome, whose distinctive qualities include: "behavioral and personality changes

Personality Changes: Originally thought to be concrete and unchanging, recent studies have found evidence that personality can change throughout a person's life.

An important idea to keep in mind is that differences in personality traits among ind ...

, loss of personal identity, cessation of scholastic activities, estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders."

In the opinion of sociology professor Benjamin Zablocki of Rutgers University, ''destructive cults'' are at high risk of becoming abusive to members, stating that such is in part due to members' adulation

Flattery (also called adulation or blandishment) is the act of giving excessive compliments, generally for the purpose of ingratiating oneself with the subject. It is also used in pick-up lines when attempting to initiate sexual or romantic cou ...

of charismatic leaders contributing to the leaders becoming corrupted by power. According to Barrett, the most common accusation made against destructive cults is sexual abuse. According to Kranenborg, some groups are risky when they advise their members not to use regular medical care. Kranenborg, Reender. 1996. "Sekten... gevaarlijk of niet? ults... dangerous or not? (in Dutch). ''Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland'' 31. Free University Amsterdam

The Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (abbreviated as ''VU Amsterdam'' or simply ''VU'' when in context) is a public research university in Amsterdam, Netherlands, being founded in 1880. The VU Amsterdam is one of two large, publicly funded research ...

. . . This may extend to physical and psychological harm.

Writing about Bruderhof communities in the book '' Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field'', Julius H. Rubin said that American religious innovation created an unending diversity of sects. These "new religious movements…gathered new converts and issued challenges to the wider society. Not infrequently, public controversy, contested narratives and litigation result." In his work ''Cults in Context'' author Lorne L. Dawson

Lorne L. Dawson is a Canadian scholar of the sociology of religion who has written about new religious movements, the brainwashing controversy, and religion and the Internet. His work is now focused on religious terrorism and the process of rad ...

writes that although the Unification Church "has not been shown to be violent or volatile," it has been described as a destructive cult by "anticult crusaders." In 2002, the German government was held by the Federal Constitutional Court to have defamed the Osho movement

The Rajneesh movement are people inspired by the Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (1931–1990), also known as Osho, particularly initiated disciples who are referred to as "neo-sannyasins". They used to be known as ''Rajneeshees'' or "Orang ...

by referring to it, among other things, as a "destructive cult" with no factual basis.

Some researchers have criticized the term ''destructive cult'', writing that it is used to describe groups which are not necessarily harmful in nature to themselves or others. In his book ''Understanding New Religious Movements'', John A. Saliba John A. Saliba is a Maltese-born Jesuit priest, a professor of religious studies at the University of Detroit Mercy and a noted writer and researcher in the field of new religious movements.

Saliba has advocated a conciliatory approach towards n ...

writes that the term is overgeneralized. Saliba sees the Peoples Temple as the "paradigm of a destructive cult", where those that use the term are implying that other groups will also commit mass suicide.

Doomsday cults

''Doomsday cult'' is an expression which is used to describe groups that believe in Apocalypticism andMillenarianism

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenariani ...

, and it can also be used to refer both to groups that predict disaster, and groups that attempt to bring it about. In the 1950s, American social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues observed members of a small UFO religion called the Seekers for several months, and recorded their conversations both prior to and after a failed prophecy from their charismatic leader. Their work was later published in the book '' When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World''. In the late 1980s, doomsday cults were a major topic of news reports, with some reporters and commentators considering them a serious threat to society. A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter found that people turned to a cataclysmic world view after they had repeatedly failed to find meaning in mainstream movements. People also strive to find meaning in global events such as the turn of the millennium when many predicted it prophetically marked the end of an age and thus the end of the world. An ancient Mayan calendar ended at the year 2012 and many anticipated catastrophic disasters would rock the Earth.

Aum Shinrikyo

In 1995, members of the Japanese doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo murdered a number of people during a sarin attack on the Tokyo subway. Aum Shrinrikyo has been involved in several violent incidents. In 1990, members of Aum Shrinrikyo murdered the family of a lawyer who was involved in a legal action against them. There were several other murders besides that brought the death toll associated with this group's acts to 27. Some were surprised by the group's ability to recruit educated young people. Scholars have attempted to explain the cause of this as feelings of social alienation that make young Japanese vulnerable to mind control techniques.Political cults

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action and

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action and ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

.Tourish, Dennis, and Tim Wohlforth. 2000. '' On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left''. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe

M. E. Sharpe, Inc., an academic publisher, was founded by Myron Sharpe in 1958 with the original purpose of publishing translations from Russian in the social sciences and humanities. These translations were published in a series of journals, the ...

. Groups that some have described as "political cults", mostly advocating far-left

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or the extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single definition. Some scholars consider ...

or far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

agendas, have received some attention from journalists and scholars. In their 2000 book '' On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left'', Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth discuss about a dozen organizations in the United States and Great Britain that they characterize as cults. In a separate article, Tourish says that in his usage:

In 1990, Lucy Patrick commented:

In Iran, a "cult of Khomeini" developed into a "secular religion". According to Iranian author Amir Taheri, Khomeini is called imam, making a "Twelver Shiism into a cult of Thirteen." Khomeini's image is engraved in giant rocks and mountain slopes, prayers begin and end with his name, and his fatwas remain valid beyond his death (something that goes against Shiite principles). Also slogans such as "God, Koran, Khomeini" or "God is One, Khomeini is the Leader" are used as war cries of the Hezballah in Iran. Even though Khomeini's photographs still hang in many government offices, it is said that by the late 1990s "Khomeini's cult had faded".

Ayn Rand Institute

Followers ofAyn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum;, . Most sources transliterate her given name as either ''Alisa'' or ''Alissa''. , 1905 – March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and p ...

have been characterized as a cult by economist Murray N. Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian m ...

during his lifetime, and later by Michael Shermer.Rothbard, Murray

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian ...

. 1972.The Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult

" Retrieved 6 June 2020. Revised editions: '' Liberty'' magazine (1987), and Center for Libertarian Studies (1990). The core group around Rand was called the "Collective", which are now defunct; the chief group which is disseminating Rand's ideas today is the Ayn Rand Institute. Although the Collective advocated an individualist philosophy, Rothbard claimed that it was organized in the manner of a " Leninist" organization.

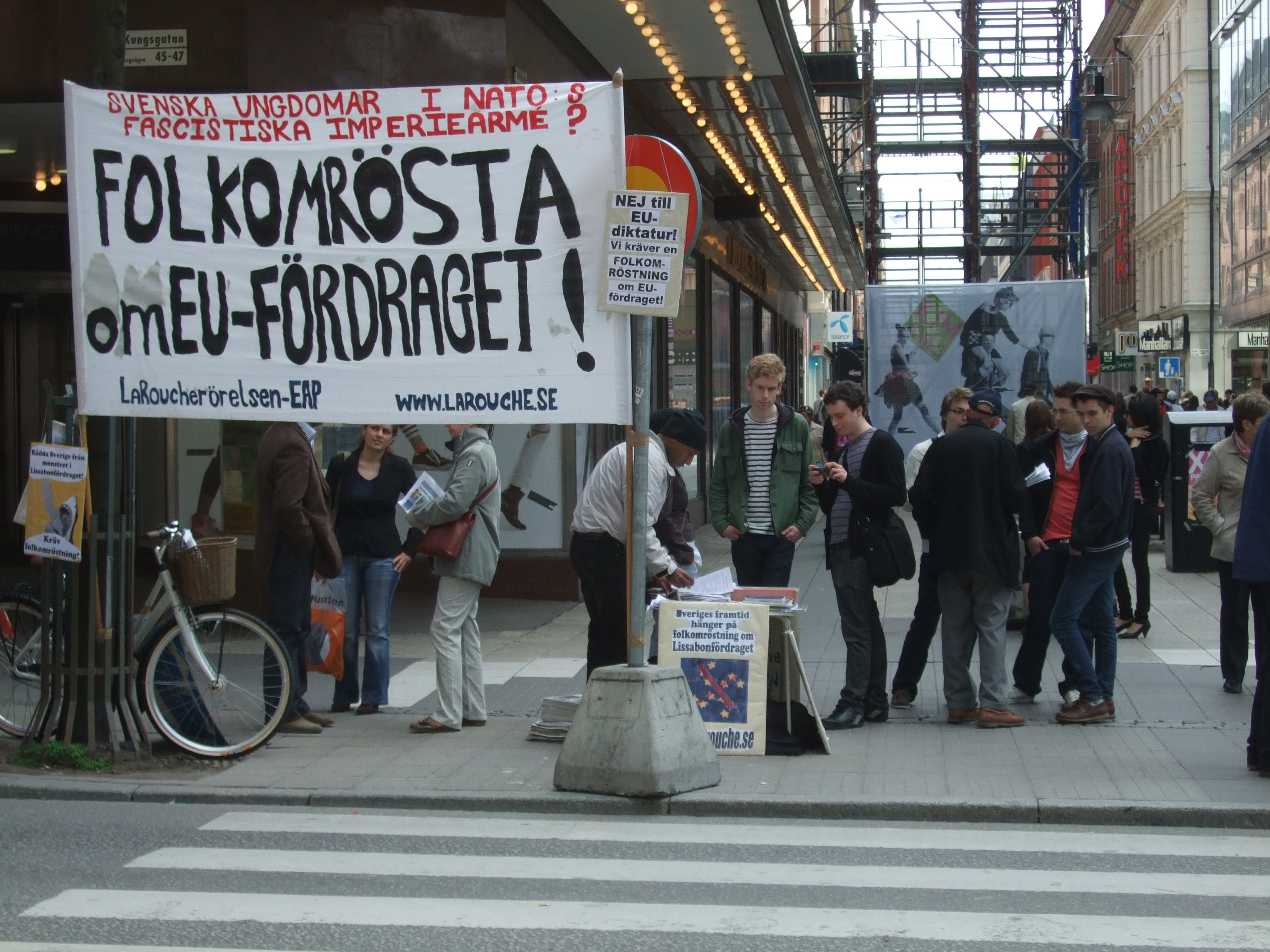

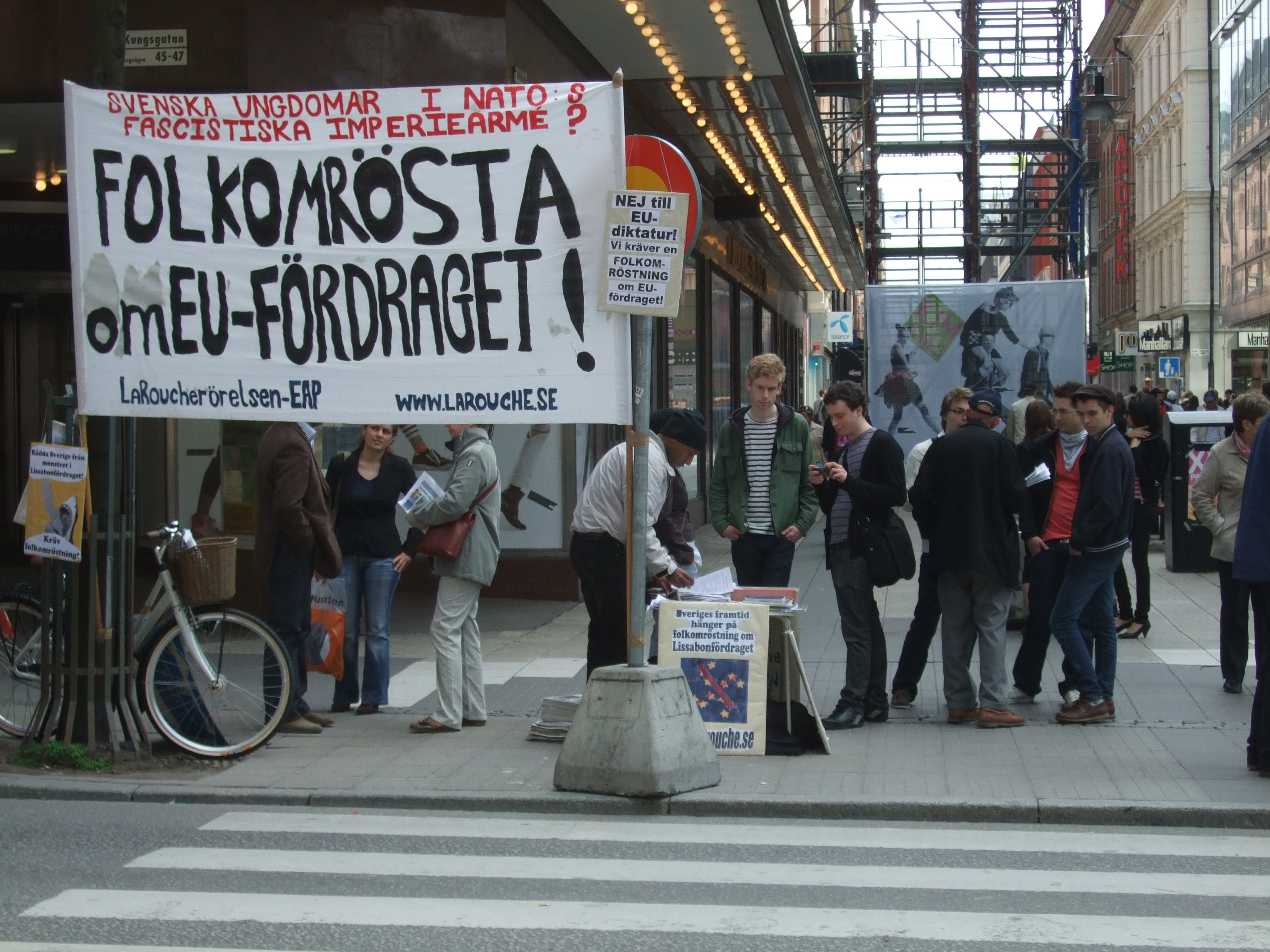

LaRouche movement

The LaRouche movement is a political and cultural network promoting the late Lyndon LaRouche and his ideas. It has included many organizations and companies around the world, which campaign, gather information and publish books and periodicals. It has been called "cult-like" by ''The New York Times''. The movement originated within the radical leftist student politics of the 1960s. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of candidates ran in stateDemocratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

primaries in the United States on the 'LaRouche platform', while Lyndon LaRouche repeatedly campaigned for presidential nomination

In United States politics and government, the term presidential nominee has two different meanings:

# A candidate for president of the United States who has been selected by the delegates of a political party at the party's national convention (al ...

. However, the LaRouche movement is often considered far-right.King 1989, pp. 132–133. During its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, the LaRouche movement developed a private intelligence agency and contacts with foreign governments.

New Acropolis

An Argentinian esoteric group founded in 1957 by former theosophistJorge Angel Livraga

Jorge is a Spanish and Portuguese given name. It is derived from the Greek name Γεώργιος (''Georgios'') via Latin ''Georgius''; the former is derived from (''georgos''), meaning "farmer" or "earth-worker".

The Latin form ''Georgius' ...

, the New Acropolis Cultural Association has been described by scholars as an ultra-conservative, neo-fascist and white supremacist paramilitary group

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

. The group itself denies such descriptions.

Unification Church

Founded by North Korea-bornSun Myung Moon

Sun Myung Moon (; born Yong Myung Moon; 6 January 1920 – 3 September 2012) was a Korean religious leader, also known for his business ventures and support for conservative political causes. A messiah claimant, he was the founder of the Unif ...

, the Unification Church (also known as the Unification movement) holds a strong anti-Communist position. In the 1940s, Moon cooperated with members of the Communist Party of Korea in the Korean independence movement against Imperial Japan. However, after the Korean War (1950–1953), he became an outspoken anti-communist. Moon viewed the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

between democracy and communism as the final conflict between God and Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

, with divided Korea as its primary front line

A front line (alternatively front-line or frontline) in military terminology is the position(s) closest to the area of conflict of an armed force's personnel and equipment, usually referring to land forces. When a front (an intentional or uninte ...

. Soon after its founding the Unification movement began supporting anti-communist organizations, including the World League for Freedom and Democracy founded in 1966 in Taipei, Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

(Taiwan), by Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, and the Korean Culture and Freedom Foundation

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or "Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 under the name Holy Spi ...

, an international public diplomacy

In international relations, public diplomacy or people's diplomacy, broadly speaking, is any of the various government-sponsored efforts aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics to establish a dialogue designed to inform and influen ...

organization which also sponsored Radio Free Asia.

In 1974 the Unification Church supported Republican President Richard Nixon and rallied in his favor after the Watergate scandal, with Nixon thanking personally for it. In 1975 Moon spoke at a government sponsored rally against potential North Korean military aggression on Yeouido Island

Yeouido (Hangul: 여의도, en, Yoi Island or Yeoui Island) is a large island (or eyot) on the Han River in Seoul, South Korea. It is Seoul's main finance and investment banking district. Its 8.4 square kilometers are home to some 30,988 people ...

in Seoul to an audience of around 1 million. The Unification movement was criticized by both the mainstream media

In journalism, mainstream media (MSM) is a term and abbreviation used to refer collectively to the various large mass news media that influence many people and both reflect and shape prevailing currents of thought.Chomsky, Noam, ''"What makes mai ...

and the alternative press for its anti-communist activism, which many said could lead to World War Three and a nuclear holocaust.Thomas Ward, 2006Give and Forget

/ref>

'' The New York Times'', 21 January 1992 In 1977, the

Subcommittee on International Organizations of the Committee on International Relations The Subcommittee on International Organizations of the Committee on International Relations (also known as the Fraser Committee) was a committee of the U.S. House of Representatives which met in 1976 and 1977 and conducted an investigation into the ...

, of the United States House of Representatives, found that the South Korean intelligence agency, the KCIA, had used the movement to gain political influence with the United States and that some members had worked as volunteers in Congressional offices. Together they founded the Korean Cultural Freedom Foundation, a nonprofit organization which acted as a public diplomacy

In international relations, public diplomacy or people's diplomacy, broadly speaking, is any of the various government-sponsored efforts aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics to establish a dialogue designed to inform and influen ...

campaign for the Republic of Korea.Spiritual warfare: the politics of the Christian rightSara Diamond, 1989, Pluto Press, Page 58 The committee also investigated possible KCIA influence on the Unification Church's campaign in support of Nixon. In 1980, members founded CAUSA International, an

anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

educational organization based in New York City."Moon's 'Cause' Takes Aim At Communism in Americas." '' The Washington Post''. August 28, 1983 In the 1980s, it was active in 21 countries. In the United States, it sponsored educational conferences for evangelical and fundamentalist Christian leadersSun Myung Moon's Followers Recruit Christians to Assist in Battle Against Communism''

Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "evange ...

'', June 15, 1985 as well as seminars and conferences for Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

staffers, Hispanic Americans and conservative activists.Church Spends Millions On Its Image'' The Washington Post'', 1984-09-17. "Another church political arm, Causa International, which preaches a philosophy it calls "God-ism," has been spending millions of dollars on expense-paid seminars and conferences for Senate staffers, Hispanic Americans and conservative activists. It also has contributed $500,000 to finance an anticommunist lobbying campaign headed by John T. (Terry) Dolan, chairman of the National Conservative Political Action Committee (NCPAC)." In 1986, CAUSA International sponsored the documentary film ''

Nicaragua Was Our Home

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

'', about the Miskito Indians of Nicaragua and their persecution at the hands of the Nicaraguan government. It was filmed and produced by USA-UWC member Lee Shapiro

Lee Shapiro (1949–1987) was an American documentary filmmaker. His one feature-length film, ''Nicaragua Was Our Home'', was released in 1986. It was filmed in Nicaragua among the Miskito people, Miskito Indians who were then fighting against Nica ...

, who later died while filming with anti-Soviet forces during the Soviet–Afghan War.

In 1983, some American members joined a public protest against the Soviet Union over its shooting down of Korean Airlines Flight 007

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (KE007/KAL007)The flight number KAL 007 was used by air traffic control, while the public flight booking system used KE 007 was a scheduled Korean Air, Korean Air Lines flight from New York City to Seoul via Anch ...

. In 1984, the HSA–UWC founded the Washington Institute for Values in Public Policy, a Washington D.C. think tank that underwrites conservative-oriented research and seminars at Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

, the University of Chicago, and other institutions.Church Spends Millions On Its Image'' The Washington Post'', 1984-09-17. In the same year, member

Dan Fefferman

Daniel G. Fefferman (known as Dan Fefferman) is a church leader and activist for the freedom of religion. He is a member of the Unification Church of the United States, a branch of the international Unification Church, founded by Sun Myung Mo ...

founded the International Coalition for Religious Freedom in Virginia, which is active in protesting what it considers to be threats to religious freedom by governmental agencies. In August 1985 the Professors World Peace Academy, an organization founded by Moon, sponsored a conference in Geneva to debate the theme "The situation in the world after the fall of the communist empire."Projections about a post-Soviet world-twenty-five years later.// Goliath Business News In April 1990, Moon visited the Soviet Union and met with President

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

. Moon expressed support for the political and economic transformations underway in the Soviet Union. At the same time, the movement was expanding into formerly communist nations.EVOLUTION IN EUROPE; New Flock for Moon Church: The Changing Soviet Studentfrom '' The New York Times'' In 1994, '' The New York Times'' recognized the movement's political influence, saying it was "a theocratic powerhouse that is pouring foreign fortunes into conservative causes in the United States." In 1998, the Egyptian newspaper ''

Al-Ahram

''Al-Ahram'' ( ar, الأهرام; ''The Pyramids''), founded on 5 August 1875, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second oldest after '' al-Waqa'i`al-Masriya'' (''The Egyptian Events'', founded 1828). It is majori ...

'' criticized Moon's "ultra-right leanings" and suggested a personal relationship with conservative Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

During the presidency of George W. Bush, Dong Moon Joo

Dong Moon Joo is a Korean American businessman. A member of the Unification Church, he is best known as the president of the church-affiliated newspaper ''The Washington Times''.

, a Unification movement member and then president of ''The Washington Times'', undertook unofficial diplomatic missions to North Korea in an effort to improve its relationship with the United States.The Bush Administration's Secret Link to North KoreaAram Roston, '' The Daily Beast'', February 7, 2012 Joo was born in North Korea and is a citizen of the United States.Unification Church president on condolence visit to N. Korea

'' Yonhap News'', December 26, 2011 The Unification Church also owns several news outlets including '' The Washington Times'', '' Insight on the News'', United Press International and the News World Communications network.As U.S. Media Ownership Shrinks, Who Covers Islam?

'' Washington Report on Middle East Affairs'', December 1997 ''Washington Times''

opinion editor

An opinion is a judgment, viewpoint, or statement that is not conclusive, rather than facts, which are true statements.

Definition

A given opinion may deal with subjective matters in which there is no conclusive finding, or it may deal with f ...

Charles Hurt

Charles Hurt (born 1971) is an American journalist and political commentator. He is currently the opinion editor of ''The Washington Times'', Fox News contributor, Breitbart News contributor, and a Drudge Report editor. Hurt's views have been con ...

was one of Donald Trump's earliest supporters in Washington, D.C. In 2018, he included Trump with Ronald Reagan, Martin Luther King Jr., Margaret Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II as "great champions of freedom." In 2016 ''The Washington Times'' did not endorse a candidate for United States president, but endorsed Trump for reelection in 2020.

Workers Revolutionary Party

In Britain, the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP), a Trotskyist group which was led by Gerry Healy and strongly supported by actress Vanessa Redgrave, has been described by others, who have been involved in the Trotskyist movement, as having been a cult or a group which displayed cult-like characteristics during the 1970s and 1980s. It is also described as such by Wohlforth and Tourish, to whom Bob Pitt, a former member of the WRP, concedes that it had a "cult-like character" though arguing that rather than being typical of the far left, this feature actually made the WRP atypical and "led to its being treated as a pariah within the revolutionary left itself."Pitt, Bob. 2000.'Cults, Sects and the Far Left'

(review). ''What Next?'' 17. .

Other groups

Gino Perente

Eugenio Mario Perente-Ramos (Gino Perente) (21 November 1937 – 18 March 1995) was the founder of the National Labor Federation (NATLFED), a collection of anti-poverty organizations in the United States. While canvassing door-to-door and operatin ...

's National Labor Federation The National Labor Federation (NATLFED) is a network of local community associations, run exclusively by volunteers, that organizes workers excluded from collective bargaining protections by U.S. labor law, specifically under the National Labor Rela ...

(NATLFED) and Marlene Dixon's now-defunct Democratic Workers Party

The Democratic Workers Party was a United States Marxist–Leninist party based in California headed by former professor Marlene Dixon, lasting from 1974–1987. One member, Janja Lalich, later became a widely cited researcher on cults. She charac ...

are an examples of political groups that have been described as "cults". A critical history of the DWP is given in ''Bounded Choice

''Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults'' is a 2004 psychology and sociology book on cults by Janja Lalich. It was published by University of California Press.

Lalich had previously studied Heaven's Gate and the Democratic Worke ...

'' by Janja Lalich, a sociologist and former DWP member. Lutte Ouvrière (LO; "Workers' Struggle") in France, publicly headed by Arlette Laguiller but revealed in the 1990s to be directed by Robert Barcia

Robert Barcia, also known as Hardy and Roger Girardot (22 July 1928 in Paris – 12 July 2009 in Créteil), was a French politician who was leader of the Internationalist Communist Union (UCI), a Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideol ...

, has often been criticized as a cult, for example, by Daniel Cohn-Bendit and his older brother Gabriel Cohn-Bendit, as well as by '' L'Humanité'' and ''Libération

''Libération'' (), popularly known as ''Libé'' (), is a daily newspaper in France, founded in Paris by Jean-Paul Sartre and Serge July in 1973 in the wake of the protest movements of May 1968. Initially positioned on the far-left of France's ...

''.

In his book ''Les Sectes Politiques: 1965–1995'' (''Political cults: 1965–1995''), French writer Cyril Le Tallec considers some religious groups that were involved in politics at that time. He included the Cultural Office of Cluny

The Cultural Office of Cluny, often named OCC (renamed Cultural Office of Cluny – National Federation of Total Animation CC – FNAGin 1978) is a Catholic-related association registered as a voluntary association, created in France by Olivier ...

, New Acropolis

New Acropolis (NA; es, Organización Internacional Nueva Acrópolis; OINA; french: Organisation Internationale Nouvelle Acropole, association internationale sans but lucratif) is a non-profit organisation originally founded in 1957 by Jorge Áng ...

, the Divine Light Mission, Tradition Family Property (TFP), Longo Maï

The Longo Maï Co-operatives are a network of agricultural co-operatives with an anti-capitalist ideological focus. Founded in 1973 in Limans, France, the network has spread in Europe and to Central America.

History

Following the events of Ma ...

, the Supermen Club, and the Association for Promotion of the Industrial Arts (Solazaref).

Several former leaders of the Groyper

Groypers, sometimes called the Groyper Army, are a group of white nationalist and far-right activists, provocateurs and internet trolls who are notable for their attempts to introduce far-right politics into mainstream conservatism in the U ...

movementan alt-right

The alt-right, an abbreviation of alternative right, is a far-right, white nationalist movement. A largely online phenomenon, the alt-right originated in the United States during the late 2000s before increasing in popularity during the mid-2 ...

faction that infuses white supremacy, Christian nationalism, and Incel ideologyhave accused Nick Fuentes of leading it like a cult, describing him as abusing and demanding absolute loyalty from his followers. Fuentes praised having a "cult-like... mentality" and admitted to "ironically" describing his own movement as a cult.

Polygamist cults

Cults that teach and practice polygamy, marriage between more than two people, most often polygyny, one man having multiple wives, have long been noted, although they are a minority. It has been estimated that there are around 50,000 members of polygamist cults in North America. Often, polygamist cults are viewed negatively by both legal authorities and mainstream society, and this view sometimes includes negative perceptions of related mainstream denominations, because of their perceived links to possibledomestic violence

Domestic violence (also known as domestic abuse or family violence) is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. ''Domestic violence'' is often used as a synonym for ''intimate partner ...

and child abuse

Child abuse (also called child endangerment or child maltreatment) is physical, sexual, and/or psychological maltreatment or neglect of a child or children, especially by a parent or a caregiver. Child abuse may include any act or failure to a ...

.

From the 1830s to 1904, members of Mormonism's largest denomination, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), performed polygamous marriages. These were called plural marriages by the church. In 1890, the president of the LDS Church, Wilford Woodruff, issued a public manifesto

A manifesto is a published declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party or government. A manifesto usually accepts a previously published opinion or public consensus or promotes a ...

announcing the cessation of new plural marriages. Anti-Mormon sentiment waned, as did opposition to statehood for Utah. The Smoot Hearings

The Reed Smoot hearings, also called Smoot hearings or the Smoot Case, were a series of Congressional hearings on whether the United States Senate should seat U.S. Senator Reed Smoot, who was elected by the Utah legislature in 1903. Smoot was an ...

in 1904, which documented that members of the LDS Church were still performing new polygamous marriages, spurred the church to issue a Second Manifesto

The "Second Manifesto" was a 1904 declaration made by Joseph F. Smith, the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), in which Smith stated the church was no longer sanctioning marriages that violated the laws of ...

, again claiming that it had ceased the practice. By 1910, the LDS Church excommunicated those who entered into or performed new polygamous marriages.Embry, Jessie L. 1994. "Polygamy." In ''Utah History Encyclopedia'', edited by A. K. Powell. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. . . Enforcement of the 1890 Manifesto caused various splinter groups to leave the LDS Church in order to continue the practice of religious polygamy. Such groups are known as Mormon fundamentalists. For example, the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

The Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church) is a religious sect of the fundamentalist Mormon denominations whose members practice polygamy. The fundamentalist Mormon movement emerged in the early 20th century, ...

is often described as a polygamist cult.

Racist cults

Sociologist and historian

Sociologist and historian Orlando Patterson

Horace Orlando Patterson (born 5 June 1940) is a Jamaican historical and cultural sociologist known for his work regarding issues of race and slavery in the United States and Jamaica, as well as the sociology of development. He is the John Cowl ...

has described the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, which arose in the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

after the Civil War, as a heretical Christian cult, and he has also described its persecution of African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

and others as a form of human sacrifice. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the existence of secret Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

cults in Germany and Austria strongly influenced the Völkisch movement

The ''Völkisch'' movement (german: Völkische Bewegung; alternative en, Folkist Movement) was a German ethno-nationalist movement active from the late 19th century through to the Nazi era, with remnants in the Federal Republic of Germany af ...

and the rise of Nazism. Modern-day white power skinhead groups in the United States tend to use the same recruitment techniques as groups which are characterized as destructive cults.

Vibert L. White, Jr., a former member of the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

and a former leading advisor to it, characterized the organization as a cult, accusing its leader Louis Farrakhan, along with other organizational leaders, of using black nationalism and religious dogma to exploit black people

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in s ...

for personal and political gain. The Nation of Islam preaches black supremacy, that its founder Wallace Fard Muhammad was a Messiah and his successor Elijah Muhammad was a divine messenger, and that white people were a race of devils to be overthrown apocalyptically.

Terrorist cults

In the book ''Jihad and Sacred Vengeance: Psychological Undercurrents of History'',psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry, the branch of medicine devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, study, and treatment of mental disorders. Psychiatrists are physicians and evaluate patients to determine whether their sy ...

Peter A. Olsson

Peter A. Olsson (born 1941, Brooklyn, New York) is an American psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and author. He is author of the book, ''Malignant Pied Pipers of Our Time: A Psychological Study of Destructive Cult Leaders from Rev. Jim Jones to Osama b ...

compares Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until Killing of Osama bin Laden, his death in 2011. Ideologically a Pan-Islamism ...

to certain cult leaders including Jim Jones, David Koresh, Shoko Asahara, Marshall Applewhite, Luc Jouret

Luc Jouret (; 18 October 1947 – 5 October 1994), born in Kikwit, Belgian Congo, was a Belgian religious group leader in Switzerland. He co-founded the ''Parti Communautaire Européen'' with Jean Thiriart, a leading member of the euro-nat ...

and Joseph Di Mambro

The Order of the Solar Temple (french: Ordre du Temple solaire, OTS) and the International Chivalric Organization of the Solar Tradition, or simply The Solar Temple, is a cult and religious sect that claims to be based upon the ideals of the ...

, and he also says that each of these individuals fit at least eight of the nine criteria for people with narcissistic personality disorder

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is a personality disorder characterized by a life-long pattern of exaggerated feelings of self-importance, an excessive need for admiration, a diminished ability or unwillingness to empathize with other ...

s. In the book ''Seeking the Compassionate Life: The Moral Crisis for Psychotherapy and Society'' authors Goldberg and Crespo also refer to Osama bin Laden as a "destructive cult leader."

At a 2002 meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA), anti-cultist Steven Hassan

Steven Alan Hassan (pronounced ; born 1953) is an American author, educator and mental health counselor specializing in destructive cults (sometimes called exit counseling). He has been described by media as "one of the world's foremost experts ...

said that Al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

fulfills the characteristics of a destructive cult, adding, in addition:

In an article on Al-Qaeda published in '' The Times'', journalist Mary Ann Sieghart

Mary Ann Corinna Howard Sieghart (born 6 August 1961) is an England, English author, journalist, radio presenter and former assistant editor of ''The Times'', where she wrote columns about politics, social affairs and life in general. She has al ...

wrote that al-Qaeda resembles a "classic cult:"

Similar to Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant adheres to an even more extremist and puritanical ideology, in which the goal is to create a state governed by '' shari'ah'' as interpreted by its religious leadership, who then brainwash and command their able-bodied male subjects to go on suicide missions

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and subs ...

, with such devices as car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roughly divided ...

s, against its enemies, including deliberately selected civilian targets, such as churches and Shi'ite mosques, among others. Subjects view this as a legitimate action; an obligation, even. The ultimate goal of this political-military

A stratocracy (from :wikt:στρατός, στρατός, ''stratos'', "army" and :wikt:κράτος, κράτος, ''kratos'', "dominion", "power", also ''stratiocracy'') is a form of government headed by military chiefs. The Separation of power ...

endeavour is to eventually usher in the end of the world in accordance with their Islamic beliefs and have the chance to participate in their version of the apocalyptic final battle, in which all of their enemies (i.e. anyone who is not on their side) would be annihilated. Such endeavour ultimately failed in 2017, though hardcore survivors have largely returned to insurgency terrorism (i.e., Iraqi insurgency, 2017–present).

The Shining Path guerrilla movement, active in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s, has variously been described as a "cult" and an intense "cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

". The Tamil Tigers have also been described as such by the French magazine .

Anti-cult movements

Christian countercult movement

In the 1940s, the long-held opposition by some establishedChristian denomination

A Christian denomination is a distinct religious body within Christianity that comprises all church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadership, theological doctrine, worsh ...

s to non-Christian religions and supposedly heretical or counterfeit Christian sects crystallized into a more organized Christian countercult movement in the United States. For those belonging to the movement, all religious groups claiming to be Christian, but deemed outside of Christian orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

, were considered cults. Christian cults are new religious movements that have a Christian background but are considered to be theologically deviant by members of other Christian churches.

The Christian countercult movement asserts that Christian sects whose beliefs are partially or wholly not in accordance with the Bible are erroneous. It also states that a religious sect can be considered a cult if its beliefs involve a denial of what they view as any of the essential Christian teachings such as salvation, the Trinity, Jesus himself as a person, the ministry of Jesus

The ministry of Jesus, in the canonical gospels, begins with his baptism in the countryside of Roman Judea and Transjordan, near the River Jordan by John the Baptist, and ends in Jerusalem, following the Last Supper with his disciples.''Chri ...

, the miracles of Jesus, the crucifixion, the resurrection of Christ, the Second Coming, and the rapture

The rapture is an Christian eschatology, eschatological position held by some Christians, particularly those of American evangelicalism, consisting of an Eschatology, end-time event when all Christian believers who are alive, along with resurre ...

.

Countercult literature usually expresses doctrinal or theological concerns and a missionary or apologetic purpose. It presents a rebuttal by emphasizing the teachings of the Bible against the beliefs of non-fundamental Christian sects. Christian countercult activist writers also emphasize the need for Christians to evangelize to followers of cults.

In his influential book ''The Kingdom of the Cults

''The Kingdom of the Cults'', first published in 1965, is a reference book of the Christian countercult movement in the United States, written by Baptist minister and counter-cultist Walter Ralston Martin.Michael J. McManus, "Eulogy for the god ...

'' (1965), Christian scholar Walter Ralston Martin defines Christian cults as groups that follow the personal interpretation of an individual, rather than the understanding of the Bible accepted by Nicene Christianity, providing the examples of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally know ...

, Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

, and the Unity Church. Martin, Walter Ralston. 965

Year 965 ( CMLXV) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Arab–Byzantine War: Emperor Nikephoros II conquers the fortress cities of Tar ...

2003. ''The Kingdom of the Cults

''The Kingdom of the Cults'', first published in 1965, is a reference book of the Christian countercult movement in the United States, written by Baptist minister and counter-cultist Walter Ralston Martin.Michael J. McManus, "Eulogy for the god ...

'' (revised ed.), edited by R. Zacharias. US: Bethany House. .Michael J. McManus, "Eulogy for the godfather of the anti-cult movement", obituary in '' The Free Lance-Star'', Fredericksburg, VA, 26 August 1989p. 8

Martin examines a large number of new religious movements; included are major groups such as

Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally know ...

, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

, Armstrongism, Theosophy, the Baháʼí Faith, Unitarian Universalism, Scientology, as well as minor groups including various New Age and groups based on Eastern religions. The beliefs of other world religions such as Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

and Buddhism are also discussed. He covers each group's history and teachings, and contrasts them with those of mainstream Christianity.

Secular anti-cult movement

converts

Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus "religious conversion" would describe the abandoning of adherence to one denomination and affiliatin ...

who did not believe their loved ones could have altered their lives so drastically by their own free will. A few psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and interpretation of how indi ...

s and sociologists working in this field suggested that brainwashing

Brainwashing (also known as mind control, menticide, coercive persuasion, thought control, thought reform, and forced re-education) is the concept that the human mind can be altered or controlled by certain psychological techniques. Brainwash ...

techniques were used to maintain the loyalty of cult members. The belief that cults brainwashed their members became a unifying theme among cult critics and in the more extreme corners of the anti-cult movement techniques like the sometimes forceful " deprogramming" of cult members was practised.

Secular cult opponents belonging to the anti-cult movement usually define a cult as a group that tends to manipulate, exploit, and control its members. Specific factors in cult behaviour are said to include manipulative and authoritarian mind control over members, communal

Communal may refer to:

*A commune or also intentional community

* Communalism (Bookchin)

* Communalism (South Asia), the South Asian sectarian ideologies

*Relating to an administrative division called comune

* Sociality in animals

*Community owne ...

and totalistic organization, aggressive proselytizing, systematic programs of indoctrination, and perpetuation in middle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Comm ...

communities. In the mass media, and among average citizens, "cult" gained an increasingly negative connotation, becoming associated with things like kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

, brainwashing, psychological abuse

Psychological abuse, often called emotional abuse, is a form of abuse characterized by a person subjecting or exposing another person to a behavior that may result in psychological trauma, including anxiety, chronic depression, or post-traumatic ...

, sexual abuse and other criminal activity, and mass suicide. While most of these negative qualities usually have real documented precedents in the activities of a very small minority of new religious groups, mass culture often extends them to any religious group viewed as culturally deviant, however peaceful or law abiding it may be.Hill, Harvey, John Hickman, and Joel McLendon. 2001. "Cults and Sects and Doomsday Groups, Oh My: Media Treatment of Religion on the Eve of the Millennium." ''Review of Religious Research