C. B. Fry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Burgess Fry (25 April 1872 – 7 September 1956) was an English sportsman, teacher, writer, editor and publisher, who is best remembered for his career as a

In his early career Fry was an enthusiastic and successful right-arm

In his early career Fry was an enthusiastic and successful right-arm  For both Sussex and England, he was closely associated with the outstanding cricketer Prince

For both Sussex and England, he was closely associated with the outstanding cricketer Prince

Fry played

Fry played

As far back as his time at Wadham College, Fry had been interested in politics, but admitted: "I take a great interest in heaps of things that I know nothing about ... politics for one".

In 1920 when his friend and former Sussex teammate Ranjitsinhji was offered and accepted the chance to become one of India's three representatives at the newly created

As far back as his time at Wadham College, Fry had been interested in politics, but admitted: "I take a great interest in heaps of things that I know nothing about ... politics for one".

In 1920 when his friend and former Sussex teammate Ranjitsinhji was offered and accepted the chance to become one of India's three representatives at the newly created

Charles Fry

– biography on the Oxford University Association Football Club web site

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Fry, C.B. 1872 births 1956 deaths Alumni of Wadham College, Oxford Association football fullbacks Barbarian F.C. players Blackheath F.C. players British magazine publishers (people) British male journalists British sportsperson-politicians Burials at St. Wystan's Church, Repton Corinthian F.C. players Cricket historians and writers Cricketers from Greater London England cricket team selectors England international footballers England Test cricket captains England Test cricketers English cricket commentators English cricketers of 1890 to 1918 English cricketers English footballers English male long jumpers English rugby union players Europeans cricketers FA Cup Final players Footballers from Croydon Gentlemen cricketers Gentlemen of England cricketers Gentlemen of the South cricketers Hampshire cricketers Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates London County cricketers Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers North v South cricketers Oxford University A.F.C. players Oxford University cricketers Oxford University Past and Present cricketers Oxford University RFC players People educated at Repton School People of the Victorian era Portsmouth F.C. players Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel Royal Navy officers Rugby union players from Croydon Southampton F.C. players Southern Football League players Sussex cricket captains Sussex cricketers Wisden Cricketers of the Year Wisden Leading Cricketers in the World Royal Naval Reserve personnel

cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by str ...

er. John Arlott

Leslie Thomas John Arlott, OBE (25 February 1914 – 14 December 1991) was an English journalist, author and cricket commentator for the BBC's ''Test Match Special''. He was also a poet and wine connoisseur. With his poetic phraseology, he be ...

described him with the words: "Charles Fry could be autocratic, angry and self-willed: he was also magnanimous, extravagant, generous, elegant, brilliant – and fun ... he was probably the most variously gifted Englishman of any age."

Fry's achievements on the sporting field included representing England at both cricket and football, an FA Cup Final

The FA Cup Final, commonly referred to in England as just the Cup Final, is the last match in the Football Association Challenge Cup. It has regularly been one of the most attended domestic football events in the world, with an official atten ...

appearance for Southampton F.C.

Southampton Football Club () is an English professional football club based in Southampton, Hampshire, which competes in the . Their home ground since 2001 has been St Mary's Stadium, before which they were based at The Dell. The club play i ...

and equalling the then-world record for the long jump

The long jump is a track and field event in which athletes combine speed, strength and agility in an attempt to leap as far as possible from a takeoff point. Along with the triple jump, the two events that measure jumping for distance as a ...

. He also reputedly turned down the throne of Albania. In later life, he suffered mental health problems, but even well into his seventies he claimed he was still able to perform his party trick: leaping from a stationary position backwards onto a mantelpiece

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and c ...

.

Education

C. B. Fry was born inCroydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensi ...

; the son of a civil servant. Both sides of his family had once been wealthy, but by 1872 were not as prosperous. After winning a scholarship, Fry was educated at Repton School

Repton School is a 13–18 co-educational, independent, day and boarding school in the English public school tradition, in Repton, Derbyshire, England.

Sir John Port of Etwall, on his death in 1557, left funds to create a grammar school whi ...

and then at Wadham College, Oxford

Wadham College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road.

Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy W ...

. His greatest strength academically was in the Classics. At Repton he won the school prizes for Latin Verse, Greek Verse, Latin Prose and French. He was also runner-up in German. His weakest subject was mathematics; he gained the headmaster's permission to study Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

instead and dispensed with maths for the rest of his academic career.

Repton has a strong tradition in football and Fry played for the under-16 Repton football side in his first term, aged thirteen. He went on to captain both the school's cricket and football teams, and also won prizes for athletics. At the age of sixteen he played for the Casuals in the F.A. Cup.

Having won a further scholarship to study at Wadham College, Oxford

Wadham College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road.

Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy W ...

, he won his university Blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when ...

in football, cricket and athletics, but narrowly failed to win a Blue in rugby union, because of an injury. Fry's status brought him into the orbit of people whose fame was already spreading far beyond Oxford, such as Max Beerbohm

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, parodist and caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the drama critic for the '' Saturd ...

, the writer and caricaturist. He gained a first in classical moderations

Honour Moderations (or ''Mods'') are a set of examinations at the University of Oxford at the end of the first part of some degree courses (e.g., Greats or '' Literae Humaniores'').

Honour Moderations candidates have a class awarded (hence the ' ...

.

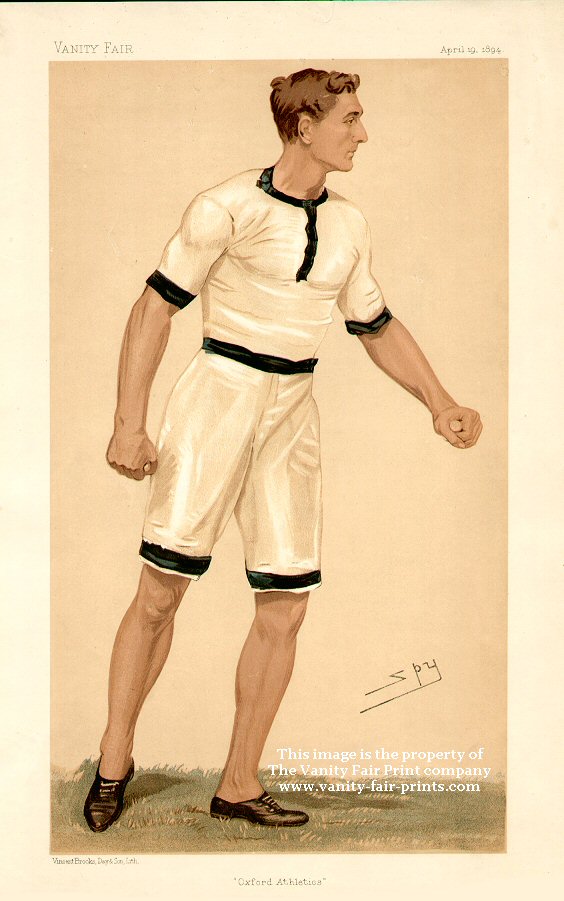

When Fry was only twenty-one, the magazine '' Vanity Fair'' published a caricature of him in its issue of 19 April 1894, with the comment: "He is sometimes known as "C.B."; but it has lately been suggested that he should be called 'Charles III'."

In his final term at Oxford Fry experienced his first (but not last) bout of mental illness, suffering a mental breakdown. There were a number of contributing factors to this. During his time at Oxford Fry had accumulated disturbingly large debts. In an attempt to alleviate his financial difficulties, Fry capitalised on his reputation to make some much-needed money. As well as writing articles (including one for ''Wisden

''Wisden Cricketers' Almanack'', or simply ''Wisden'', colloquially the Bible of Cricket, is a cricket reference book published annually in the United Kingdom. The description "bible of cricket" was first used in the 1930s by Alec Waugh in a ...

''), he did some private tutoring but although such activities reduced his debts they did not clear them and, further increased the intense pressure on his time. Fry's continuing indebtedness provides the most obvious explanation for his acceptance of an offer to do some nude modelling. These financial problems combined with his mother being seriously ill, placed an unbearable strain on him. Although he was able to sit his final exams, he was hardly in any fit state to do so, having hardly read a line for weeks. The result was Fry scraping a Fourth, bringing one of Oxford's most spectacular and successful careers to an inglorious end. So in the summer of 1895, only months after being the toast of Oxford, Fry found himself saddled with mounting debts and no way with which to repay them. In the short term, cricket came to his rescue. He was offered, and accepted, the chance to tour South Africa as a member of Lord Hawke

Martin Bladen Hawke, 7th Baron Hawke (16 August 1860 – 10 October 1938), generally known as Lord Hawke, was an English amateur cricketer active from 1881 to 1911 who played for Yorkshire and England. He was born in Willingham by Stow, near G ...

's 1895–96 England touring party.

Personal life

In 1898, Fry married Beatrice Holme Sumner (1862–1946), daughter of Arthur Holme Sumner, of Hatchlands Park, Guildford, Surrey; they had three children. Beatrice was ten years Fry's senior, and known for her 'fiery, strong-willed, aggressive' personality; she was reckoned to be 'a cruel and domineering woman', and Fry 'lived in fear of her for the duration of their marriage', as 'she made him thoroughly miserable and he tried to stay away from her as much as possible'. His unhappy marriage impacted Fry's mental health; his daughter-in-law observed: 'I should think anyone would have a breakdown married to her". At Beatrice's death, they had been married for 48 years; Fry 'adjusted to her death with great equanimity and even her children showed all the freedom of the newly liberated'. In 1984, their sonStephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

said: 'My mother ruined my father's life'. He and his son, Charles Fry, also played first-class cricket.

Sporting career

Apart from his other sporting achievements stated below, Fry was also a decentshot putter

The shot put is a track and field event involving "putting" (throwing) a heavy spherical ball—the ''shot''—as far as possible. The shot put competition for men has been a part of the modern Olympics since their revival in 1896, and women's c ...

, hammer thrower

The hammer throw is one of the four throwing events in regular track and field competitions, along with the discus throw, shot put and javelin.

The "hammer" used in this sport is not like any of the tools also called by that name. It consists ...

and ice skater

Ice skating is the self-propulsion and gliding of a person across an ice surface, using metal-bladed ice skates. People skate for various reasons, including recreation (fun), exercise, competitive sports, and commuting. Ice skating may be perf ...

, representing Wadham in the inter-College races on Blenheim lake in the winter of 1894–95 and coming close to an unofficial Blue as a member of the Oxford team who took on Cambridge on the Fens, as well as being a proficient golfer.

Cricket

Fry played for Surrey in 1891 (but not in any first-class fixtures),Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

1892–1895 (winning Blues in all four years and captaining the university in 1894, meaning that he was simultaneously not only captain of both the university cricket and football teams but president of the varsity athletics club as well) Sussex 1894–1908 (captain 1904–1908), and Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

, 1909–1921. First selected by England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

for the tour of South Africa in 1895–96, he captained England in his final six Test matches in 1912, winning four and drawing two. He twice scored Test centuries

A century is a period of 100 years. Centuries are numbered ordinally in English and many other languages. The word ''century'' comes from the Latin ''centum'', meaning ''one hundred''. ''Century'' is sometimes abbreviated as c.

A centennial or ...

: 144 v Australia in 1905 hitting 23 fours in just over hours, batting at number four, and 129 opening the batting against South Africa in 1907.

As a highly effective right-handed batsman who batted at, or near the top of the order, Fry scored 30,886 first-class runs at an average of 50.22, a particularly high figure for an era when scores were generally lower than today. At the end of his cricketing career in 1921–22, he had the second highest average of any retired player with over 10,000 runs: only his Sussex and England colleague Ranjitsinhji

Colonel H. H. Shri Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II, Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, (10 September 1872 – 2 April 1933), often known as Ranji or K. S. Ranjitsinhji, was the ruler of the Indian princely state of Nawanagar from 1907 to 1933, as Ma ...

had retired with a better career average. He headed the batting averages (qualification minimum 20 innings) for six English seasons (in 1901, 1903, 1905, 1907, 1911 and 1912). Against Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

, the strongest county bowling attack of Fry's time, he averaged a remarkable 63.60 over the course of his career, including back to back scores of 177 and 229 against them in 1904. GL Jessop said that calmness was at the heart of his batting and that he was a superb judge of a run as well as being fast between the wickets.

In his early career Fry was an enthusiastic and successful right-arm

In his early career Fry was an enthusiastic and successful right-arm fast-medium

Fast bowling (also referred to as pace bowling) is one of two main approaches to bowling in the sport of cricket, the other being spin bowling. Practitioners of pace bowling are usually known as ''fast'' bowlers, ''quicks'', or ''pacemen''. T ...

bowler. He returned his career best figures of 6–78 in the 1895 Varsity match

A varsity match is a fixture (especially of a sporting event or team) between two university teams, particularly Oxford and Cambridge. The Scottish Varsity rugby match between the University of St Andrews and the University of Edinburgh at Murrayf ...

, and he twice took ten wickets in a match

In cricket, a ten-wicket haul occurs when a bowler takes ten wickets in either a single innings or across both innings of a two-innings match. The phrase ten wickets in a match is also used.

Taking ten wickets in a match at Lord's earns the bo ...

: 5–75 and 5–102 for the Gentlemen of England

Cricket, and hence English amateur cricket, probably began in England during the medieval period but the earliest known reference concerns the game being played c.1550 by children on a plot of land at the Royal Grammar School, Guildford, Surrey ...

against I Zingari

I Zingari (from dialectalized Italian , meaning "the Gypsies"; corresponding to standard Italian ') are English and Australian amateur cricket clubs, founded in 1845 and 1888 respectively. It is the oldest and perhaps the most famous of the ' ...

in 1895, and 5–81 and 5–66 for Sussex against Nottinghamshire in 1896 (a match in which he also scored 89 and 65). The late 1890s saw a re-emergence of the throwing

Throwing is an action which consists in accelerating a projectile and then releasing it so that it follows a ballistic trajectory, usually with the aim of impacting a remote target. This action is best characterized for animals with prehensile ...

controversy in cricket. Several professional bowlers including Arthur Mold

Arthur Webb Mold (27 May 1863 – 29 April 1921) was an English professional cricketer who played first-class cricket for Lancashire as a fast bowler between 1889 and 1901. A ''Wisden'' Cricketer of the Year in 1892, he was selected for ...

and Ernie Jones were no-balled and forced to retire. Fry's bowling action was criticised by opponents and teammates, and it was only a matter of time before he too was no-balled by umpire Jim Phillips.

Fry scored 94 first-class centuries, including an unprecedented six consecutive centuries in 1901. No one else has scored more consecutive hundreds. On 12 September 1901, playing for the Rest of England against Yorkshire at Lord's, he scored 105, which was his sixth consecutive first-class century. He made his highest first-class score of 258 not out in 1911, a season which led to his recall to the England Test team as captain in 1912. In 1921 Fry was once again considered for the Test side. The Selection Committee asked him to play in the First Test match at Nottingham under the captaincy of Johnny Douglas

John William Henry Tyler Douglas (3 September 1882 – 19 December 1930) was an English cricketer who was active in the early decades of the twentieth century. Douglas was an all-rounder who played for Essex County Cricket Club from 1901 to 1 ...

, with a view to taking over the captaincy for the remainder of the series if, as they anticipated, things went wrong. Fry declined on the basis that there was no sense in recalling a forty-nine-year-old merely as a player, but stated that he would consider returning as captain. As England were badly beaten at Nottingham the Selection Committee again pressed Fry to return for the Second Test but once again he declined, due to poor form. Following another heavy defeat in the Second Test the Selection Committee made a further attempt to persuade Fry to return for the Third Test as captain, a job he was now keen to accept. He injured a finger taking a catch during Hampshire's match with the Australians. In the short term, the injury did not appear too serious: he scored a half-century in Hampshire's first innings and, when they followed on in reply to the Australians' massive total he top scored with 37. Furthermore, in his next match against Nottinghamshire he scored 61 in the first innings (but registered a duck in the second). It appears however that the injury was affecting his fielding more than his batting and, for last time, C.B. felt obliged to stand down from the side for the next Test. Fry later commentated on cricket matches, being called "one of the most eloquent cricket commentator

__NOTOC_is a list of notable media commentators and writers on the sport of cricket from around the world.

A number of famous players have had a second career as writers or commentators. However, many commentators never played the game at a prof ...

s of all time."

For both Sussex and England, he was closely associated with the outstanding cricketer Prince

For both Sussex and England, he was closely associated with the outstanding cricketer Prince Ranjitsinhji

Colonel H. H. Shri Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II, Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, (10 September 1872 – 2 April 1933), often known as Ranji or K. S. Ranjitsinhji, was the ruler of the Indian princely state of Nawanagar from 1907 to 1933, as Ma ...

, the future Jam Sahib

Jam Sahib ( gu, જામ સાહેબ), is the title of the ruling prince of Nawanagar, now known as Jamnagar in Gujarat, an Indian princely state.

Jam Sahibs of Nawanagar

References

External links

Nawanagar History and Genealogyat '' ...

of Nawanagar. Their contrasting batting styles complemented one another (Fry being an orthodox, technically correct batsman, and Ranji being noted for his innovation, particularly his use of the leg glance

In cricket, batting is the act or skill of hitting the ball with a bat to score runs and prevent the loss of one's wicket. Any player who is currently batting is, since September 2021, officially referred to as a batter (historically, the ...

). Their friendship lasted well into the 1920s, and when Ranjitsinhji became one of India's three representatives at the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, he took Fry with him as his assistant.

Athletics

In athletics, Fry won Blues in all four years at Oxford 1892–95, representing the university against Cambridge in the long jump in 1892, 1893, 1894 and 1895; the high jump in 1892 and the 100 yards in 1893 and 1894. In 1892 Fry broke the British long jump record with a jump of and a year later on 4 March 1893 equalled the worldlong jump

The long jump is a track and field event in which athletes combine speed, strength and agility in an attempt to leap as far as possible from a takeoff point. Along with the triple jump, the two events that measure jumping for distance as a ...

record of (tied with the American Charles Reber). This is often incorrectly claimed to have stood as a world record for 21 years, but this length of time actually only refers to how long he held the university record, Cambridge's H. S. O. Ashington adding three-quarters of an inch to Fry's distance in 1913. Fry's shared world record was broken on 5 September 1894 by Ireland's J. J. Mooney.

In the first contest between universities from different countries, Oxford v Yale at the Queen's Club, West Kensington, in 1894, Fry came third in the long jump and won the 100 yards. In addition to being an outstanding long jumper, sprinter and high jumper, Fry was also a talented hurdler

Hurdling is the act of jumping over an obstacle at a high speed or in a sprint. In the early 19th century, hurdlers ran at and jumped over each hurdle (sometimes known as 'burgles'), landing on both feet and checking their forward motion. Today, ...

, once competing against Godfrey Shaw the champion hurdler of the time, who beat him but told him, as Fry later recalled: "He was sure if I took up hurdling seriously I might win the championship." Fry was also president of the Oxford University athletics club in 1894.

Football

Fry's achievements extended to association football. A defender with exceptional pace, Fry learned his football atRepton School

Repton School is a 13–18 co-educational, independent, day and boarding school in the English public school tradition, in Repton, Derbyshire, England.

Sir John Port of Etwall, on his death in 1557, left funds to create a grammar school whi ...

, where he played for and captained the school team. While still at school he also played for the famous amateur club the Casuals, for whom he found himself turning out in an FA Cup tie at the age of sixteen. Fry went on to win Blues in each of his four years at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

captaining the side in his third year. In 1891, he joined another famous amateur club, the Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians ( grc, Α΄ ᾽Επιστολὴ πρὸς Κορινθίους) is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-aut ...

, going on to make a total of 74 appearances for them between 1891 and 1903 scoring four goals. Although extremely proud of his amateur status, he decided that entering the professional game would enhance his chance of international honours. He chose Southampton F.C. (''The Saints''), as the leading lights in the Southern League, and also because The Dell was conveniently close to his home. He made his debut for Southampton (as an amateur) on 26 December 1900,against Tottenham Hotspur

Tottenham Hotspur Football Club, commonly referred to as Tottenham () or Spurs, is a professional football club based in Tottenham, London, England. It competes in the Premier League, the top flight of English football. The team has playe ...

and went on to help them win the Southern League title during that 1900–01 season.

Fry's game was probably a little too refined for the hurly-burly of professional football

In professional sports, as opposed to amateur sports, participants receive payment for their performance. Professionalism in sport has come to the fore through a combination of developments. Mass media and increased leisure have brought larg ...

, he never relished the aerial challenges that were more prevalent in the professional game, but having worked tirelessly to improve his heading ability he achieved his aim of international honours when (along with Southampton's goalkeeper, Jack Robinson), he was picked to play as a full-back for England in the match against Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

on 9 March 1901 (played in Southampton).

The following season (1901–02), Southampton reached the FA Cup Final

The FA Cup Final, commonly referred to in England as just the Cup Final, is the last match in the Football Association Challenge Cup. It has regularly been one of the most attended domestic football events in the world, with an official atten ...

, playing against Sheffield United

Sheffield United Football Club is a professional football club in Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England, which compete in the . They are nicknamed "the Blades" due to Sheffield's history of cutlery production. The team have played home games at ...

, which was drawn 1–1, but Southampton lost the replay, 2–1. Although he had moments during the cup run in which he excelled, his positional play was sometimes questioned. Fry played in all eight of the FA Cup games for Southampton that season, but in only nine Southern League matches, with Bill Henderson being forced to give way whenever Fry was available. The following season, he played twice at centre forward, without success, but Southampton released him partly due to his lack of availability. Fry made 25 first-team appearances for Southampton. He then joined Southampton's local rivals Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, making his debut for them on 21 January 1903. Fry made three appearances for Portsmouth (as an amateur) before retiring from football due to injury.

Rugby union

Fry played

Fry played rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In it ...

for Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

, narrowly missing out on a Blue in his final year due to injury, Blackheath, for whom he made ten appearances, and the Barbarians

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be les ...

, for whom he made three appearances. Fry was also chosen, as he later recalled, as the "first reserve for the South against the North" – a match that was, in effect, an England trial. Unfortunately for Fry, no one pulled out before the match and, as there were no substitutions allowed in rugby at the time, he did not get to play.

Acrobatics

Fry's party trick was to leap from a stationary position on the floor backwards onto amantelpiece

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and c ...

; he would face the mantelpiece, crouch down, take a leap upwards, turn in the air, and bow to the gallery with his feet planted on the shelf. Persuasion would occasionally get him to perform this turn at country houses, much to the interest of the guests.

Career outside sport

Teaching

In 1896 Fry took up a teaching position atCharterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

. Two years later in 1898 he left the profession, moving on to a successful and much more lucrative and less time-consuming career in journalism. He later recalled: "I could earn by journalism three times the income for the expenditure of a tenth of the time." In December 1908 he became the Captain Superintendent of the Training Ship ''Mercury'', a nautical school primarily designed to prepare boys for service in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

; this was run by his wife Beatrice from 1885 to 1946, she having founded the school with her lover (and father of her illegitimate children), the rich banker Charles Hoare. She subjected the boys, 'hounded from morn to night', to 'barbarities' including ceremonial floggings of extreme violence and forced boxing matches inflicted as punishment. Fry held this position until he resigned to make way for a younger man in 1950. Eventually he was given the rank of captain in the Royal Naval Reserve

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) is one of the two volunteer reserve forces of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Together with the Royal Marines Reserve, they form the Maritime Reserve. The present RNR was formed by merging the original Ro ...

(RNR). Alan Gibson

Norman Alan Stewart Gibson (28 May 1923 – 10 April 1997) was an English journalist, writer and radio broadcaster, best known for his work in connection with cricket, though he also sometimes covered football and rugby union. At various times ...

wrote: "He ... would stride about in his uniform looking, as I think it was Robertson-Glasgow who said, every inch like six admirals." Interviewed about the ''Mercury'', and his role in its development, he was addressed as 'Commander C. B. Fry'.

Politics

As far back as his time at Wadham College, Fry had been interested in politics, but admitted: "I take a great interest in heaps of things that I know nothing about ... politics for one".

In 1920 when his friend and former Sussex teammate Ranjitsinhji was offered and accepted the chance to become one of India's three representatives at the newly created

As far back as his time at Wadham College, Fry had been interested in politics, but admitted: "I take a great interest in heaps of things that I know nothing about ... politics for one".

In 1920 when his friend and former Sussex teammate Ranjitsinhji was offered and accepted the chance to become one of India's three representatives at the newly created League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

he took Fry with him as his assistant. It was whilst working for Ranjitsinhji at the League of Nations, in Geneva, that Fry claimed to have been offered the throne of Albania. Whether this offer genuinely occurred has been questioned, but Fry was definitely approached about the vacant Albanian throne and therefore seems to have been considered a credible candidate for the post.

He stood (unsuccessfully) as a Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

candidate for parliament for the Brighton constituency in 1922. Fry's presence certainly brought some welcome glamour and excitement to the election, and his campaign was given extra colour by the appearance, at an election meeting, of Dame Clara Butt

Dame Clara Ellen Butt, (1 February 1872 – 23 January 1936) was an English contralto and one of the most popular singers from the 1890s through to the 1920s. She had an exceptionally fine contralto voice and an agile singing technique, and imp ...

, the opera singer (and a close personal friend of the Frys). He won 22,059 votes, 4,785 fewer than the Conservative victor.

He later fought the seat of Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshir ...

in 1923, losing by just 219 votes, and the Oxford by-election in 1924, where he was defeated by 1,842 votes.

Writing, editing, publishing and broadcasting

Books by Fry include: *''The Book of Cricket: A New Gallery of Famous Players'' (1899), editor, appeared in 14 weekly parts. *''Giants of the Game: Being Reminiscences of the Stars of Cricket from Daft Down to the Present Day'' (c. 1900), with R. H. Lyttleton, W. J. Ford &George Giffen

George Giffen (27 March 1859 – 29 November 1927) was a cricketer who played for South Australia and Australia. An all-rounder who batted in the middle order and often opened the bowling with medium-paced off-spin, Giffen captained Australia ...

.

*''Great Batsmen: Their Methods at a Glance'' (1905), with George W Beldam, who provided the photographs.

*''Great Bowlers and Fielders: Their Methods at a Glance'' (1907), with George W. Beldam

*''A Mother's Son'' (1907), a novel written in collaboration with his wife.

*''Cricket: Batsmanship'' (1912).

*''Key-Book of The League of Nations''.

*''Life Worth Living: Some Phases Of An Englishman'' (1939), his autobiography.

*''Cricket on the Green For Club And Village Cricketers And For Boys'' (1947), with R. S. Young.

He is also believed to have written much of '' The Jubilee Book of Cricket'' (1897), of which the nominal author was Ranji. He wrote prefaces and introductions for a number of other cricket books, and wrote articles on cricket and football for ''The Strand Magazine

''The Strand Magazine'' was a monthly British magazine founded by George Newnes, composed of short fiction and general interest articles. It was published in the United Kingdom from January 1891 to March 1950, running to 711 issues, though the ...

'' in the early years of the 20th century. In the 1930s, he wrote a column for the London ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'', which covered many topics. The column was credited with a considerable increase in the paper's circulation. He launched and edited ''C. B. Fry's Magazine.'' In his magazine he promoted toys such as the diabolo

The diabolo ( ; commonly misspelled ''diablo'') is a juggling or circus prop consisting of an axle () and two cups (hourglass/egg timer shaped) or discs derived from the Chinese yo-yo. This object is spun using a string attached to two hand ...

. A History and Bibliography of Fry's Magazine was published in December 2022 by Sports History Publishing.

His broadcasting career began in 1936 with commentary for the BBC on a match between Middlesex and Surrey. He declined to join the panel on ''Any Questions

''Any Questions?'' is a British topical discussion programme "in which a panel of personalities from the worlds of politics, media, and elsewhere are posed questions by the audience".

It is typically broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Fridays at 8 ...

'' but in 1945 began a successful stint on ''The Brains Trust

''The Brains Trust'' was an informational BBC radio and later television programme popular in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 1950s, on which a panel of experts tried to answer questions sent in by the audience.

History

The series was ...

''.

In 1946 he was one of the BBC radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

commentary team for the Tests between England and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. In 1953 he gave a 3-hour interview to the BBC which was edited down to 30 minutes for the programme ''Frankly Speaking''. In 1955, he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews

Eamonn Andrews, (19 December 1922 – 5 November 1987) was an Irish radio and television presenter, employed primarily in the United Kingdom from the 1950s to the 1980s. From 1960 to 1964 he chaired the Radio Éireann Authority (now the RTÉ ...

for the fifth episode of the new television show '' This Is Your Life''. Amongst the friends gathered to relive his best moments were Jack Hobbs

Sir John Berry Hobbs (16 December 1882– 21 December 1963), always known as Jack Hobbs, was an English professional cricketer who played for Surrey from 1905 to 1934 and for England in 61 Test matches between 1908 and 1930. Known as "The Mast ...

and Sydney Barnes

Sydney Francis Barnes (19 April 1873 – 26 December 1967) was an English professional cricketer who is regarded as one of the greatest bowlers of all time. He was right-handed and bowled at a pace that varied from medium to fast-medium wit ...

.

Later life

In the 1920s, Fry's mental health started to deteriorate severely. He had encountered mental health problems earlier in his life, experiencing a breakdown during his final year at Oxford, which meant that, although academically brilliant, he achieved a poor degree. In the late 1920s, he had a major breakdown and became deeply paranoid. He reached breaking point in 1928 during a visit to India, becoming convinced that an Indian had cast a spell on him. For the rest of his life, he dressed in bizarrely unconventional clothes. He did recover enough to become a popular writer on cricket and other sports, and even into his sixties he entertained hopes of becoming a Hollywood star. At one point when he was staying in Brighton he was supposed to have gone for a walk along the beach early in the morning and suddenly shed all his clothes, trotting around stark naked. In 1934, as reported in his 1939 autobiography, ''Life Worth Living'', he visited Germany with the idea of forging stronger links between the uniformed British youth organisations, such as theBoy Scouts

Boy Scouts may refer to:

* Boy Scout, a participant in the Boy Scout Movement.

* Scouting, also known as the Boy Scout Movement.

* An organisation in the Scouting Movement, although many of these organizations also have female members. There are ...

, and the Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

, so that both groups could learn from each other. Fry met Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

who greeted him with a Nazi salute

The Nazi salute, also known as the Hitler salute (german: link=no, Hitlergruß, , Hitler greeting, ; also called by the Nazi Party , 'German greeting', ), or the ''Sieg Heil'' salute, is a gesture that was used as a greeting in Nazi Germany. Th ...

which he returned with a Nazi salute of his own. He failed to persuade von Ribbentrop that Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

should take up cricket to Test level. Some members of the Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

were welcomed at TS ''Mercury'', and Fry was still enthusiastic about them in 1938, just prior to the outbreak of war. Fry's laudatory statements about Hitler persisted through his autobiography's third impression in July 1941 but appear to have been purged in the fourth impression (1947).

He retired from his position at TS ''Mercury'' in 1950, and died in 1956, in Hampstead, London. The English writer and critic Neville Cardus

Sir John Frederick Neville Cardus, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (2 April 188828 February 1975) was an English writer and critic. From an impoverished home background, and mainly self-educated, he became ''The Manchester Gua ...

wrote the following words for Fry's obituary: Fry must be counted among the most fully developed and representative Englishmen of his period; and the question arises whether, had fortune allowed him to concentrate on the things of the mind, not distracted by the lure of cricket, a lure intensified by his increasing mastery over the game, he would not have reached a high altitude in politics or critical literature. But he belonged – and it was his glory – to an age not obsessed by specialism; he was one of the last of the English tradition of the amateur, theHis ashes were buried in the graveyard of Repton Parish Church, next to Repton School's Priory. In 2008, his grandson, Jonathan Fry (chairman of the governors at Repton), was in attendance at the rededication of Fry's grave, which was inscribed with, "1872 C B Fry 1956. Cricketer, scholar, athlete, Author – The Ultimate All-rounder'.connoisseur A connoisseur (French traditional, pre-1835, spelling of , from Middle-French , then meaning 'to be acquainted with' or 'to know somebody/something') is a person who has a great deal of knowledge about the fine arts; who is a keen appreciator o ..., and, in the most delightful sense of the word, thedilettante Dilettante or dilettantes may refer to: * An amateur, someone with a non-professional interest * A layperson, the opposite of an expert * ''Dilettante'' (album), a 2005 album by Ali Project * ''Dilettantes'' (album), a 2008 album by You Am I * D ....

Honours

Southampton F.C. *FA Cup

The Football Association Challenge Cup, more commonly known as the FA Cup, is an annual knockout football competition in men's domestic English football. First played during the 1871–72 season, it is the oldest national football competi ...

finalist: 1902

Events

January

* January 1

** The Nurses Registration Act 1901 comes into effect in New Zealand, making it the first country in the world to require state registration of nurses. On January 10, Ellen Dougherty becomes the world' ...

Two Brighton & Hove

Brighton and Hove () is a city and unitary authority in East Sussex, England. It consists primarily of the settlements of Brighton and Hove, alongside neighbouring villages.

Often referred to synonymously as Brighton, the City of Brighton and ...

buses (429 and 829) were named "C B Fry" in his honour.

See also

* List of English cricket and football players *List of cricket and rugby union players

This is a list of sports people who have played both cricket and rugby union at a high level. First-class or List A cricket, provincial rugby and international cricket or rugby are considered to be high level for the purposes of this list. To be e ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Charles Fry

– biography on the Oxford University Association Football Club web site

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Fry, C.B. 1872 births 1956 deaths Alumni of Wadham College, Oxford Association football fullbacks Barbarian F.C. players Blackheath F.C. players British magazine publishers (people) British male journalists British sportsperson-politicians Burials at St. Wystan's Church, Repton Corinthian F.C. players Cricket historians and writers Cricketers from Greater London England cricket team selectors England international footballers England Test cricket captains England Test cricketers English cricket commentators English cricketers of 1890 to 1918 English cricketers English footballers English male long jumpers English rugby union players Europeans cricketers FA Cup Final players Footballers from Croydon Gentlemen cricketers Gentlemen of England cricketers Gentlemen of the South cricketers Hampshire cricketers Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates London County cricketers Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers North v South cricketers Oxford University A.F.C. players Oxford University cricketers Oxford University Past and Present cricketers Oxford University RFC players People educated at Repton School People of the Victorian era Portsmouth F.C. players Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel Royal Navy officers Rugby union players from Croydon Southampton F.C. players Southern Football League players Sussex cricket captains Sussex cricketers Wisden Cricketers of the Year Wisden Leading Cricketers in the World Royal Naval Reserve personnel