Byzantine–Bulgarian War Of 913–927 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ByzantineBulgarian war of 913927 ( bg, Българо–византийска война от 913–927) was fought between the

The Magyar devastation of the country's north-eastern regions during the War of 894–896 exposed the vulnerability of Bulgaria's borders to foreign intervention under the influence of

The Magyar devastation of the country's north-eastern regions during the War of 894–896 exposed the vulnerability of Bulgaria's borders to foreign intervention under the influence of

At the beginning of the 10th century, the

At the beginning of the 10th century, the

In 912 Leo VI died and was succeeded by his brother

In 912 Leo VI died and was succeeded by his brother  The first steps of the regency were to attempt to divert Simeon's attack. Nicholas Mystikos sent a letter which, while praising the wisdom of Simeon, accused him of attacking an "orphan child" (i.e., ConstantineVII) who had done nothing to insult him, but his efforts were in vain. Toward the end of July 913 the Bulgarian monarch launched a campaign at the head of a large army, and in August he reached Constantinople unopposed. The head of the Byzantine chancery,

The first steps of the regency were to attempt to divert Simeon's attack. Nicholas Mystikos sent a letter which, while praising the wisdom of Simeon, accused him of attacking an "orphan child" (i.e., ConstantineVII) who had done nothing to insult him, but his efforts were in vain. Toward the end of July 913 the Bulgarian monarch launched a campaign at the head of a large army, and in August he reached Constantinople unopposed. The head of the Byzantine chancery,

Following the victories in 917, the way to Constantinople lay open. However, Simeon had to deal with the Serbian prince Petar Gojniković, who had responded positively to the Byzantine proposal for an anti-Bulgarian coalition. An army was dispatched under the command of ''kavhan'' Theodore Sigritsa and general Marmais. The two persuaded Petar Gojniković to meet them, whereupon they seized him and sent him to Preslav, where he died in prison. The Bulgarians replaced Petar with Pavle Branović, a grandson of prince

Following the victories in 917, the way to Constantinople lay open. However, Simeon had to deal with the Serbian prince Petar Gojniković, who had responded positively to the Byzantine proposal for an anti-Bulgarian coalition. An army was dispatched under the command of ''kavhan'' Theodore Sigritsa and general Marmais. The two persuaded Petar Gojniković to meet them, whereupon they seized him and sent him to Preslav, where he died in prison. The Bulgarians replaced Petar with Pavle Branović, a grandson of prince

After the threat from Serbia was eliminated in 917, Simeon personally led a campaign in the Theme of Hellas and penetrated deep to the south, reaching the

After the threat from Serbia was eliminated in 917, Simeon personally led a campaign in the Theme of Hellas and penetrated deep to the south, reaching the  In the spring of 919, the military setbacks suffered by the Byzantines the previous two years triggered another change in Byzantine rule when Admiral Romanos Lekapenos forced Zoe Karbonopsina back to a monastery and quickly rose to prominence. In April, Lekapenos' daughter

In the spring of 919, the military setbacks suffered by the Byzantines the previous two years triggered another change in Byzantine rule when Admiral Romanos Lekapenos forced Zoe Karbonopsina back to a monastery and quickly rose to prominence. In April, Lekapenos' daughter

By 922, although the Bulgarians controlled almost the entire Balkan peninsula, Simeon's main objective remained out of his reach. The Bulgarian monarch was aware that he needed a navy to conquer Constantinople. Simeon decided to turn to

By 922, although the Bulgarians controlled almost the entire Balkan peninsula, Simeon's main objective remained out of his reach. The Bulgarian monarch was aware that he needed a navy to conquer Constantinople. Simeon decided to turn to

After the failure to secure an alliance with the Arabs, in September 923 or 924 SimeonI once again appeared in Byzantine Thrace. The Bulgarians pillaged the outskirts of Constantinople, burned the Church of St. Mary of the Spring and set up camp at the walls of Constantinople. SimeonI demanded a meeting with RomanosI in order to establish a temporary truce to deal with the Serbian threat. The Byzantines, eager to cease hostilities, agreed. Prior to the meeting at the suburb of Kosmidion, the Bulgarians took precautions and carefully inspected the specially prepared platformthey still remembered the failed Byzantine attempt to assassinate Khan

After the failure to secure an alliance with the Arabs, in September 923 or 924 SimeonI once again appeared in Byzantine Thrace. The Bulgarians pillaged the outskirts of Constantinople, burned the Church of St. Mary of the Spring and set up camp at the walls of Constantinople. SimeonI demanded a meeting with RomanosI in order to establish a temporary truce to deal with the Serbian threat. The Byzantines, eager to cease hostilities, agreed. Prior to the meeting at the suburb of Kosmidion, the Bulgarians took precautions and carefully inspected the specially prepared platformthey still remembered the failed Byzantine attempt to assassinate Khan

By the terms of the treaty, the Byzantines officially recognized the imperial title of the Bulgarian monarchs but insisted on the formula that the emperor of the Bulgarians be considered a "spiritual son" of the Byzantine emperor. Despite the wording, the title of the Bulgarian rulers equalled that of their Byzantine counterparts. The

By the terms of the treaty, the Byzantines officially recognized the imperial title of the Bulgarian monarchs but insisted on the formula that the emperor of the Bulgarians be considered a "spiritual son" of the Byzantine emperor. Despite the wording, the title of the Bulgarian rulers equalled that of their Byzantine counterparts. The

Bulgarian Empire

In the medieval history of Europe, Bulgaria's status as the Bulgarian Empire ( bg, Българско царство, ''Balgarsko tsarstvo'' ) occurred in two distinct periods: between the seventh and the eleventh centuries and again between th ...

and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

for more than a decade. Although the war was provoked by the Byzantine emperor Alexander's

Alexander's is a real estate investment trust that owns 7 properties in New York metropolitan area, including 731 Lexington Avenue, the headquarters of Bloomberg L.P. It is controlled by Vornado Realty Trust. It was founded by George Farkas an ...

decision to discontinue paying an annual tribute to Bulgaria, the military and ideological initiative was held by Simeon I of Bulgaria, who demanded to be recognized as Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

and made it clear that he aimed to conquer not only Constantinople but the rest of the Byzantine Empire, as well.

In 917, the Bulgarian army

The Bulgarian Land Forces ( bg, Сухопътни войски на България, Sukhopŭtni voĭski na Bŭlgariya, lit=Ground Forces of Bulgaria) are the ground warfare branch of the Bulgarian Armed Forces. The Land Forces were established ...

dealt a crushing defeat to the Byzantines at the Battle of Achelous, resulting in Bulgaria's total military supremacy in the Balkans. The Bulgarians again defeated the Byzantines at Katasyrtai in 917, Pegae

Karabiga (Karabuga) is a town in Biga District, Çanakkale Province, in the Marmara region of Turkey. It is located at the mouth of the Biga River, on a small east-facing bay, known as Karabiga Bay. Its ancient name was Priapus or Priapos ( g ...

in 921 and Constantinople in 922. The Bulgarians also captured the important city of Adrianople

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to th ...

and seized the capital of the Theme of Hellas, Thebes, deep in southern Greece. Following the disaster at Achelous, Byzantine diplomacy

Byzantine diplomacy concerns the principles, methods, mechanisms, ideals, and techniques that the Byzantine Empire espoused and used in order to negotiate with other states and to promote the goals of its foreign policy. Dimitri Obolensky asserts ...

incited the Principality of Serbia

The Principality of Serbia ( sr-Cyrl, Књажество Србија, Knjažestvo Srbija) was an autonomous state in the Balkans that came into existence as a result of the Serbian Revolution, which lasted between 1804 and 1817. Its creation wa ...

to attack Bulgaria from the west, but this assault was easily contained. In 924, the Serbs ambushed and defeated a small Bulgarian army on its way to Serbia, provoking a major retaliatory campaign that ended with Bulgaria's annexation of Serbia at the end of that year.

Simeon was aware that he needed naval support to conquer Constantinople and in 922 sent envoys to the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyn ...

caliph Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh/ʿUbayd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn (), 873 – 4 March 934, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdi Billah, was the founder of the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate, the only major Shi'a caliphate in Islamic history, and the ...

in Mahdia to negotiate the assistance of the powerful Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, No ...

navy. The caliph agreed to send his own representatives to Bulgaria to arrange an alliance but his envoys were captured en route by the Byzantines near the Calabrian coast. Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos

Romanos I Lekapenos ( el, Ρωμανός Λεκαπηνός; 870 – 15 June 948), Latinized as Romanus I Lecapenus, was Byzantine emperor from 920 until his deposition in 944, serving as regent for the infant Constantine VII.

Origin

Romanos ...

managed to avert a Bulgarian–Arab alliance by showering the Arabs with generous gifts. By the time of his death in May 927, Simeon controlled almost all Byzantine possessions in the Balkans, but Constantinople remained out of his reach.

In 927, both countries were exhausted by the huge military efforts that had taken a heavy toll on the population and economy. Simeon's successor Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a s ...

negotiated a favourable peace treaty. The Byzantines agreed to recognize him as Emperor of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church ( bg, Българска православна църква, translit=Balgarska pravoslavna tsarkva), legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria ( bg, Българска патриаршия, links=no, translit=Balgarsk ...

as an independent Patriarchate, as well as to pay an annual tribute. The peace was reinforced with a marriage between Peter and Romanos's granddaughter Irene Lekapene

Irene Lekapene (born Maria; bg, Ирина Лакапина, el, Μαρία/Ειρήνη Λεκαπηνή, died ca. 966) was the Empress consort of Peter I of Bulgaria. She was а daughter of Christopher Lekapenos, son and co-emperor of Romanos ...

. This agreement ushered in a period of 40 years of peaceful relations between the two powers, a time of stability and prosperity for both Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire.

Prelude

Political background

In the first years after his accession to the throne in 893, Simeon successfully defended Bulgaria's commercial interests, acquired territory between the Black Sea and theStrandzha

Strandzha ( bg, Странджа, also transliterated as ''Strandja'', ; tr, Istranca , or ) is a mountain massif in southeastern Bulgaria and the European part of Turkey. It is in the southeastern part of the Balkans between the plains of T ...

mountains, and imposed an annual tribute on the Byzantine Empire as a result of the Byzantine–Bulgarian war of 894–896

The Byzantine–Bulgarian war of 894–896 ( bg, Българо–византийска война от 894–896) was fought between the Bulgarian Empire and the Byzantine Empire as a result of the decision of the Byzantine emperor Leo VI t ...

. The outcome of the war confirmed Bulgarian domination in the Balkans, but Simeon knew that he needed to consolidate his political, cultural and ideological base in order to fulfil his ultimate goal of claiming an imperial title for himself and eventually assuming the throne in Constantinople. He implemented an ambitious construction programme in Bulgaria's new capital, Preslav

The modern Veliki Preslav or Great Preslav ( bg, Велики Преслав, ), former Preslav ( bg, link=no, Преслав; until 1993), is a city and the seat of government of the Veliki Preslav Municipality (Great Preslav Municipality, new B ...

, so that the city would rival the splendour of the Byzantine capital. Simeon continued the policy of his father Boris I (r.852–889) of establishing and disseminating Bulgarian culture, turning the country into the literary and spiritual centre of Slavic Europe

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Sla ...

. The Preslav

The modern Veliki Preslav or Great Preslav ( bg, Велики Преслав, ), former Preslav ( bg, link=no, Преслав; until 1993), is a city and the seat of government of the Veliki Preslav Municipality (Great Preslav Municipality, new B ...

and literary schools, founded under BorisI, reached their apogee during the reign of his successor. It was at this time that the Cyrillic alphabet

, bg, кирилица , mk, кирилица , russian: кириллица , sr, ћирилица, uk, кирилиця

, fam1 = Egyptian hieroglyphs

, fam2 = Proto-Sinaitic

, fam3 = Phoenician

, fam4 = Gr ...

was invented, most likely by the Bulgarian scholar Clement of Ohrid.

The Magyar devastation of the country's north-eastern regions during the War of 894–896 exposed the vulnerability of Bulgaria's borders to foreign intervention under the influence of

The Magyar devastation of the country's north-eastern regions during the War of 894–896 exposed the vulnerability of Bulgaria's borders to foreign intervention under the influence of Byzantine diplomacy

Byzantine diplomacy concerns the principles, methods, mechanisms, ideals, and techniques that the Byzantine Empire espoused and used in order to negotiate with other states and to promote the goals of its foreign policy. Dimitri Obolensky asserts ...

. As soon as the peace with Byzantium had been signed, Simeon sought to secure the Bulgarian positions in the western Balkans. After the death of the Serb prince Mutimir

Mutimir ( sr, Мутимир, el, Μουντιμῆρος) was prince of Serbia from ca. 850 until 891. He defeated the Bulgar army, allied himself with the Byzantine emperor and ruled the first Serbian Principality when the Christianization o ...

(r.850–891), several members of the ruling dynasty fought over the throne of the Principality of Serbia

The Principality of Serbia ( sr-Cyrl, Књажество Србија, Knjažestvo Srbija) was an autonomous state in the Balkans that came into existence as a result of the Serbian Revolution, which lasted between 1804 and 1817. Its creation wa ...

until Petar Gojniković

Petar Gojniković or Peter of Serbia ( sr-cyr, Петар Гојниковић, gr, Πέτρος; ca. 870 – 917) was Prince of the Serbs from 892 to 917. He ruled and expanded the First Serbian Principality and won several wars against ...

established himself as a prince in 892. In 897 Simeon agreed to recognize Petar and put him under his protection, resulting in a twenty-year period of peace and stability to the west. However, Petar was not content with his subordinate position and sought ways to achieve independence.

The internal situation of the Byzantine Empire at the beginning of the 10th century was seen by Simeon as a sign of weakness. There was an attempt to murder emperor Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI, called the Wise ( gr, Λέων ὁ Σοφός, Léōn ho Sophós, 19 September 866 – 11 May 912), was Byzantine Emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty (although his parentage is unclear), he was very well r ...

(r.886–912) in 903 and a rebellion of the commander of the Eastern army Andronikos Doukas in 905. The situation further deteriorated as the emperor entered into a feud with the Ecumenical Patriarch

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), New Rome and ''primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of th ...

Nicholas Mystikos

Nicholas I Mystikos or Nicholas I Mysticus ( el, Νικόλαος Α΄ Μυστικός, ''Nikolaos I Mystikos''; 852 – 11 May 925) was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from March 901 to February 907 and from May 912 to his death ...

over his fourth marriage, to his mistress Zoe Karbonopsina

Zoe Karbonopsina, also Karvounopsina or Carbonopsina, ( el, Ζωὴ Καρβωνοψίνα, translit=Zōē Karbōnopsina), was an empress and regent of the Byzantine empire. She was the fourth spouse of the Byzantine Emperor Leo VI the Wise and th ...

. In 907, LeoVI had the patriarch deposed.

Crisis of 904

At the beginning of the 10th century, the

At the beginning of the 10th century, the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, No ...

completed the conquest of Sicily

Sicily ( it, Sicilia , ) is the list of islands in the Mediterranean, largest island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. The Strait of Messina divides it from the region of Calabria in Southern Italy. I ...

and from 902 began attacking Byzantine shipping and towns in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

. In 904, they sacked the empire's second-largest city, Thessalonica, taking 22,000 captives and leaving the city virtually empty. Simeon decided to exploit that opportunity, and the Bulgarian army appeared in the vicinity of the deserted city. By securing and settling Thessalonica, the Bulgarians would have gained an important port on the Aegean Sea and would have cemented their hold on the western Balkans, creating a permanent threat to Constantinople. Aware of the danger, the Byzantines sent the experienced diplomat Leo Choirosphaktes Leo Choirosphaktes, sometimes Latinized as Choerosphactes ( el, Λέων Χοιροσφάκτης) and also known as Leo Magistros or Leo Magister, was a Byzantine official who rose to high office under Emperor Basil I the Macedonian () and served ...

to negotiate a solution. The course of the negotiations is unknownin a surviving letter to emperor LeoVI the Wise, Choirosphaktes boasted that he had "convinced" the Bulgarians not to take the city but did not mention more details. However, an inscription found near the village of Narash testifies that since 904 the border between the two countries ran only to the north of Thessalonica. As a result of the negotiations, Bulgaria secured the territorial gains acquired in Macedonia during the reign of Khan Presian I (r.836–852) and expanded its territory further south, taking possession of most of the region. The western section of the Byzantine–Bulgarian border ran from the Falakro mountain through the town of Serres

Sérres ( el, Σέρρες ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of North ...

, which lay on the Byzantine side, then turned south-west to Narash, crossed the Vardar

The Vardar (; mk, , , ) or Axios () is the longest river in North Macedonia and the second longest river in Greece, in which it reaches the Aegean Sea at Thessaloniki. It is long, out of which are in Greece, and drains an area of around . Th ...

river at the modern village of Axiohori, ran through Mount Paiko

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, C ...

, passed east of Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city ('' polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroen ...

through the Vermio and Askio mountains, crossed the river Haliacmon

The Haliacmon ( el, Αλιάκμονας, ''Aliákmonas''; formerly: , ''Aliákmon'' or ''Haliákmōn'') is the longest river flowing entirely in Greece, with a total length of . In Greece there are three rivers longer than Haliakmon, Maritsa ( el ...

south of the town of Kostur, which lay in Bulgaria, ran through the Gramos

Gramos ( sq, Gramoz, Mali i Gramozit; rup, Gramosta, Gramusta; el, Γράμος or Γράμμος) is a mountain range on the border of Albania and Greece. The mountain is part of the northern Pindus mountain range. Its highest peak, at the ...

mountains, then followed the river Aoös until its confluence with the river Drino

The Drino or Drinos ( sq, Drino, el, Δρίνος) is a river in southern Albania and northwestern Greece, tributary of the Vjosë. Its source is in the northwestern part of the Ioannina regional unit, near the village Delvinaki. It flows init ...

, and finally turned west, reaching the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

at the town of Himarë

Himarë ( sq-definite, Himara; el, Χειμάρρα, ''Cheimarra'' or Χιμάρα, ''Chimara'') is a municipality and region in Vlorë County, southern Albania. The municipality has a total area of and consists of the administrative units of H ...

.

Beginning of the war and Simeon I's coronation

In 912 Leo VI died and was succeeded by his brother

In 912 Leo VI died and was succeeded by his brother Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, who set about reversing many of LeoVI's policies and reinstated Nicholas Mystikos as patriarch. As the diplomatic protocol of the time prescribed, Simeon sent emissaries to confirm the peace in late 912 or early 913. According to the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes Continuatus

''Theophanes Continuatus'' ( el, συνεχισταί Θεοφάνους) or ''Scriptores post Theophanem'' (, "those after Theophanes") is the Latin name commonly applied to a collection of historical writings preserved in the 11th-century Vat. g ...

, Simeon informed him that "he would honour the peace if he was to be treated with kindness and respect, as it was under emperor Leo. However, Alexander, overwhelmed by madness and folly, ignominiously dismissed the envoys, made threats to Simeon and thought he would intimidate him. The peace was broken and Simeon decided to raise arms against the Christians he Byzantines" The Bulgarian ruler, who was seeking a ''casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one b ...

'' to claim the imperial title, took the opportunity to wage war. Unlike his predecessors, Simeon's ultimate ambition was to assume the throne of Constantinople as a Roman emperor, creating a joint Bulgarian–Roman state. The historian John Fine argues that the provocative policy of Alexander did little to influence Simeon's decision, as he had already planned an invasion, having taken into account that on the Byzantine throne sat a man who was unpopular, inexperienced and possibly alcoholic and whose successor, Constantine VII

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe K ...

, was a sickly little boy, considered by many to be illegitimate. While Bulgaria was preparing for war, on 6June 913 Alexander died, leaving Constantinople in chaos with an under-aged emperor under the regency of patriarch Mystikos.

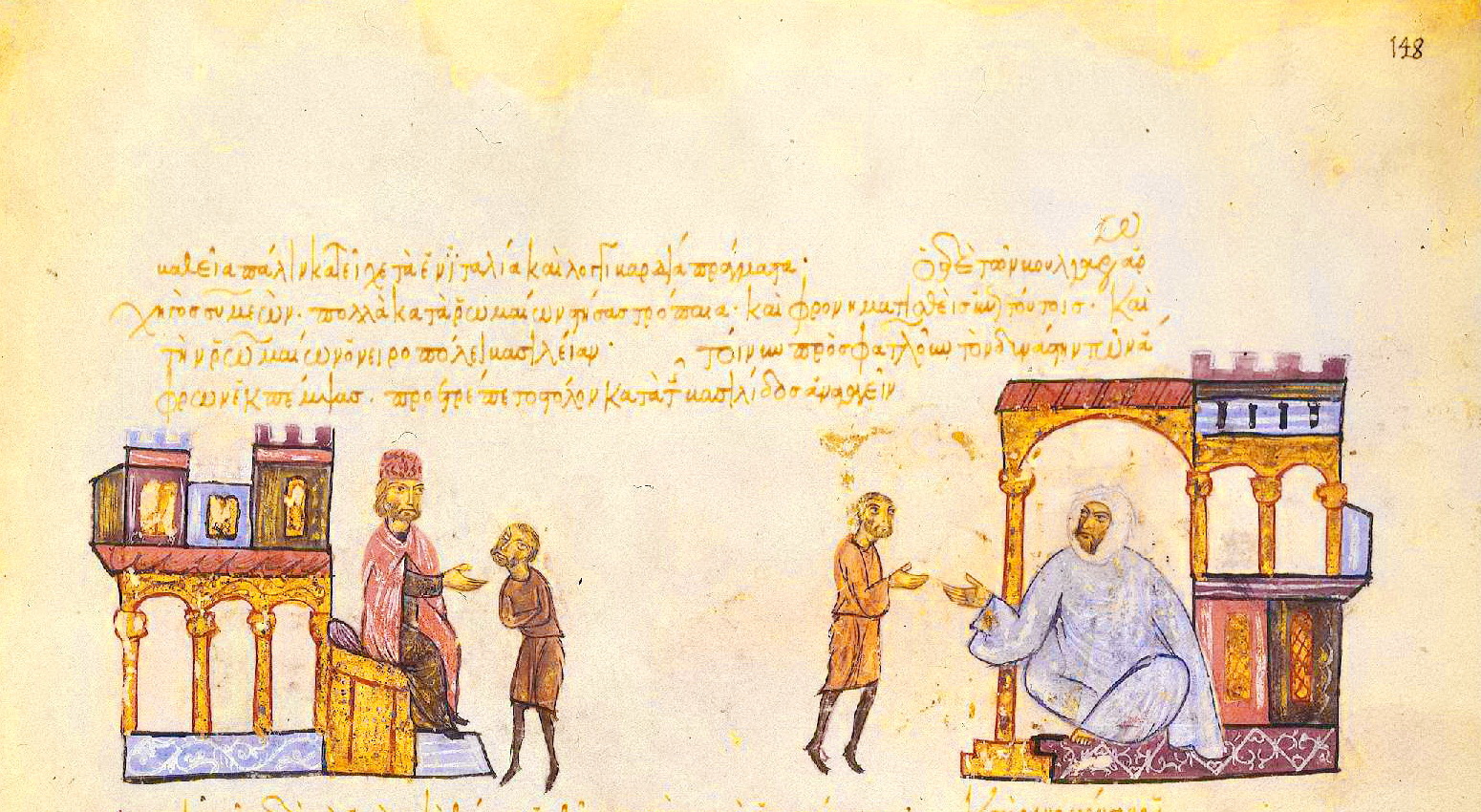

The first steps of the regency were to attempt to divert Simeon's attack. Nicholas Mystikos sent a letter which, while praising the wisdom of Simeon, accused him of attacking an "orphan child" (i.e., ConstantineVII) who had done nothing to insult him, but his efforts were in vain. Toward the end of July 913 the Bulgarian monarch launched a campaign at the head of a large army, and in August he reached Constantinople unopposed. The head of the Byzantine chancery,

The first steps of the regency were to attempt to divert Simeon's attack. Nicholas Mystikos sent a letter which, while praising the wisdom of Simeon, accused him of attacking an "orphan child" (i.e., ConstantineVII) who had done nothing to insult him, but his efforts were in vain. Toward the end of July 913 the Bulgarian monarch launched a campaign at the head of a large army, and in August he reached Constantinople unopposed. The head of the Byzantine chancery, Theodore Daphnopates Theodore Daphnopates ( el, Θεόδωρος Δαφνοπάτης) was a senior Byzantine official and author. He served as imperial secretary, and possibly ''protasekretis'', under three emperors, Romanos I Lekapenos, Constantine VII Porphyrogenneto ...

, wrote about the campaign fifteen years later: "There was an earthquake, felt even by those who lived beyond the Pillars of Hercules

The Pillars of Hercules ( la, Columnae Herculis, grc, Ἡράκλειαι Στῆλαι, , ar, أعمدة هرقل, Aʿmidat Hiraql, es, Columnas de Hércules) was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank t ...

." The Bulgarians besieged the city and constructed ditches from the Golden Horn

The Golden Horn ( tr, Altın Boynuz or ''Haliç''; grc, Χρυσόκερας, ''Chrysókeras''; la, Sinus Ceratinus) is a major urban waterway and the primary inlet of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey. As a natural estuary that connects with ...

to the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by th ...

at the Marmara Sea

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

. Since Simeon had studied at the University of Constantinople

The Imperial University of Constantinople, sometimes known as the University of the Palace Hall of Magnaura ( el, Πανδιδακτήριον τῆς Μαγναύρας), was an Eastern Roman educational institution that could trace its corpor ...

and was aware that the city was impregnable to a land attack without maritime support, those actions were a demonstration of power, not an attempt to assault the city. Soon, the siege was lifted and ''kavhan

The ''kavkhan'' ( grc-x-byzant, καυχάνος; bg, кавха̀н) was one of the most important officials in the First Bulgarian Empire.

Role and status

According to the generally accepted opinion, he was the second most important person ...

'' (first minister) Theodore Sigritsa was sent to offer peace. Simeon had two demandsto be crowned Emperor of the Bulgarians and to betroth his daughter to ConstantineVII, thus becoming father-in-law and guardian of the infant emperor.

After negotiations between Theodore Sigritsa and the regency, a feast was organised in honour of Simeon's two sons in the Palace of Blachernae

The Palace of Blachernae ( el, ). was an imperial Byzantine residence in the suburb of Blachernae, located in the northwestern section of Constantinople (today located in the quarter of Ayvansaray in Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey). The area of the pal ...

presided over personally by ConstantineVII. Patriarch Nicholas Mystikos went to the Bulgarian camp to meet the Bulgarian ruler in the midst of his entourage. Simeon prostrated himself before the Patriarch, who instead of an imperial crown placed upon Simeon's head his own patriarchal crown. The Byzantine chronicles, who were hostile to Simeon, had presented the ceremony as a sham, but modern historians, such as John Fine, Mark Whittow and George Ostrogorsky

Georgiy Aleksandrovich Ostrogorskiy (russian: Георгий Александрович Острогорский; 19 January 1902 – 24 October 1976), known in Serbian as Georgije Aleksandrovič Ostrogorski ( sr-Cyrl, Георгије Алекс ...

, argue that Simeon was too experienced to be fooled and that he was indeed crowned Emperor of the Bulgarians (in Bulgarian, Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

). The sources suggest that Nicholas Mystikos also agreed to Simeon's second condition, which could have paved Simeon's route to become co-emperor and eventually emperor of the Romans. Having achieved his goal, Simeon returned to Preslav in triumph, after he and his sons were honoured with many gifts. To mark this achievement, Simeon changed his seals to read "Simeon, peacemaking emperor, ay you reign formany years".

Battle of Achelous

The agreement concluded in August 913 proved to be short-lived. Two months later, ConstantineVII's mother, Zoe Karbonopsina, was allowed to return to Constantinople from exile. In February 914 she overthrew the regency of Nicholas Mystikos in a palace coup. She was reluctantly proclaimed empress by Mystikos, who retained his post as a Patriarch. Her first order was to revoke all concessions given to the Bulgarian monarch by the regency, provoking military retaliation. In the summer of 914 theBulgarian army

The Bulgarian Land Forces ( bg, Сухопътни войски на България, Sukhopŭtni voĭski na Bŭlgariya, lit=Ground Forces of Bulgaria) are the ground warfare branch of the Bulgarian Armed Forces. The Land Forces were established ...

invaded the themes of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to th ...

and Macedonia. Simultaneously, the Bulgarian troops penetrated into the regions of Dyrrhachium and Thessalonica to the west. Thrace's largest and most important city, Adrianople

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

, was besieged and captured in September and the local population recognized Simeon as its ruler. However, the Byzantines promptly regained the city in exchange for a huge ransom.

To deal with the Bulgarian threat for good, the Byzantines took measures to end the conflict with the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

in the east and attempted to create a wide anti-Bulgarian coalition. Two envoys were sent to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, where they secured peace with caliph al-Muqtadir

Abu’l-Faḍl Jaʿfar ibn Ahmad al-Muʿtaḍid ( ar, أبو الفضل جعفر بن أحمد المعتضد) (895 – 31 October 932 AD), better known by his regnal name Al-Muqtadir bi-llāh ( ar, المقتدر بالله, "Mighty in God"), wa ...

in June 917. The ''strategos'' of Dyrrhachium, Leo Rhabdouchos, was instructed to negotiate with the Serbian prince Petar Gojniković, who was a Bulgarian vassal but was willing to renounce Bulgarian suzerainty. However, the court in Preslav was warned about the negotiations by prince Michael of Zahumlje

Michael of Zahumlje (reign usually dated c. 910–935), also known as Michael Višević (Serbo-Croatian: ''Mihailo Višević'', Serbian Cyrillic: Михаило Вишевић) or rarely as Michael Vuševukčić,Mihanovich, ''The Croatian nation i ...

, a loyal ally of Bulgaria, and Simeon was able to prevent an immediate Serb attack. The Byzantine attempts to approach the Magyars were also successfully countered by the Bulgarian diplomacy. The general John Bogas was sent with rich gifts to the Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks tr, Peçenek(ler), Middle Turkic: , ro, Pecenegi, russian: Печенег(и), uk, Печеніг(и), hu, Besenyő(k), gr, Πατζινάκοι, Πετσενέγοι, Πατζινακίται, ka, პა� ...

, who inhabited the steppes to the north-east of Bulgaria. The Bulgarians had already established strong connections with the Pechenegs, including through marriages, and Bogas' mission proved to be a hard one. He did manage to convince some tribes to send aid, but eventually the Byzantine navy

The Byzantine navy was the naval force of the East Roman or Byzantine Empire. Like the empire it served, it was a direct continuation from its Imperial Roman predecessor, but played a far greater role in the defence and survival of the state tha ...

refused to transport them to the south of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

river, probably as a result of the jealousy that existed between Bogas and the ambitious admiral Romanos Lekapenos

Romanos I Lekapenos ( el, Ρωμανός Λεκαπηνός; 870 – 15 June 948), Latinized as Romanus I Lecapenus, was Byzantine emperor from 920 until his deposition in 944, serving as regent for the infant Constantine VII.

Origin

Romanos ...

.

The Byzantines were forced to fight alone, but the peace with the Arabs allowed them to amass their whole army, including the troops stationed in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. These forces were placed under the command of the Domestic of the Schools

The office of the Domestic of the Schools ( gr, δομέστικος τῶν σχολῶν, domestikos tōn scholōn) was a senior military post of the Byzantine Empire, extant from the 8th century until at least the early 14th century. Originally ...

Leo Phokas the Elder

Leo Phokas ( el, , ) was an early 10th-century Byzantine general of the noble Phokas clan. As Domestic of the Schools, the Byzantine army's commander-in-chief, he led a large-scale campaign against the Bulgarians in 917, but was heavily defeated ...

. Before marching to battle the soldiers bowed to "the life-giving True Cross and vowed to die for one another". With his western and northern borders secure, Simeon was also able to muster a large host. The two armies clashed on 20August 917 near the Achelous river

The Achelous ( el, Αχελώος, grc, Ἀχελῷος ''Akhelôios''), also Acheloos, is a river in western Greece. It is long. It formed the boundary between Acarnania and Aetolia of antiquity. It empties into the Ionian Sea. In ancient ...

in the vicinity of Anchialus. Initially, the Byzantines were successful, and the Bulgarians began an orderly retreat, but when Leo Phokas lost his horse, confusion spread among the Byzantine troops, who according to the chronicler John Skylitzes

John Skylitzes, commonly Latinized as Ioannes, la, Johannes, label=none, la, Iōannēs, label=none Scylitzes ( el, Ἰωάννης Σκυλίτζης, ''Iōánnēs Skylítzēs'', or el, Σκυλίτση, ''Skylítsē'', label=none ; la, ...

had low morale. Simeon, who was monitoring the battlefield from the nearby heights, ordered a counter-attack and personally led the Bulgarian cavalry. The Byzantine ranks broke and in the words of Theophanes Continuatus "a bloodshed occurred, that had not happened in centuries". Almost the whole Byzantine army was annihilated and only a few, including Leo Phokas, managed to reach the port of Messembria and flee to safety on ships.

Once again, Nicholas Mystikos was summoned in an attempt to stop the Bulgarian onslaught. In a letter to Simeon, the patriarch insisted that the purpose of the Byzantine attack had been not to destroy Bulgaria but to force Simeon to evacuate his troops from the regions of Thessalonica and Dyrrhachium. Yet he admitted that this was not an excuse for the Byzantine invasion and pleaded that as a good Christian Simeon should forgive his fellow Christians. The efforts of Nicholas Mystikos were in vain, and the Bulgarian army penetrated deep into Byzantine territory. Leo Phokas gathered another host but the Byzantines were heavily defeated in the battle of Katasyrtai }

The battle of Katasyrtai (Kατασυρται) occurred in the fall of 917, shortly after the striking Bulgarian triumph at Achelous near the village of the same name close to the Byzantine capital Constantinople, (now Istanbul). The result was a ...

just outside Constantinople in a night combat.

Campaigns against the Serbs

Following the victories in 917, the way to Constantinople lay open. However, Simeon had to deal with the Serbian prince Petar Gojniković, who had responded positively to the Byzantine proposal for an anti-Bulgarian coalition. An army was dispatched under the command of ''kavhan'' Theodore Sigritsa and general Marmais. The two persuaded Petar Gojniković to meet them, whereupon they seized him and sent him to Preslav, where he died in prison. The Bulgarians replaced Petar with Pavle Branović, a grandson of prince

Following the victories in 917, the way to Constantinople lay open. However, Simeon had to deal with the Serbian prince Petar Gojniković, who had responded positively to the Byzantine proposal for an anti-Bulgarian coalition. An army was dispatched under the command of ''kavhan'' Theodore Sigritsa and general Marmais. The two persuaded Petar Gojniković to meet them, whereupon they seized him and sent him to Preslav, where he died in prison. The Bulgarians replaced Petar with Pavle Branović, a grandson of prince Mutimir

Mutimir ( sr, Мутимир, el, Μουντιμῆρος) was prince of Serbia from ca. 850 until 891. He defeated the Bulgar army, allied himself with the Byzantine emperor and ruled the first Serbian Principality when the Christianization o ...

, who had long lived in Preslav. Thus, Serbia was turned into a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sovere ...

until 921.

In an attempt to bring Serbia under their control, in 920 the Byzantines sent Zaharija Pribislavljević, another of Mutimir's grandsons, to challenge the rule of Pavle. Zaharija was either captured by the Bulgarians en route or by Pavle, who had him duly delivered to Simeon. Either way, Zaharija ended up in Preslav. Despite the setback, the Byzantines persisted and eventually bribed Pavle to switch sides after lavishing much gold on him. In response, in 921 Simeon sent a Bulgarian army headed by Zaharija. The Bulgarian intervention was successful, Pavle was easily deposed, and once again a Bulgarian candidate was placed on the Serbian throne. This did not last long because Zaharija was raised in Constantinople where he was heavily influenced by the Byzantines. Soon, Zaharija openly declared his loyalty to the Byzantine Empire and commenced hostilities against Bulgaria. In 923 or 924 Simeon sent a small army led by Theodore Sigritsa and Marmais, but they were ambushed and killed. Zaharija sent their heads to Constantinople.

This action provoked a major retaliatory campaign in 924. A large Bulgarian force was dispatched, accompanied by a new candidate, Časlav, who was born in Preslav to a Bulgarian mother. The Bulgarians ravaged the countryside and forced Zaharija to flee to the Kingdom of Croatia. This time, however, the Bulgarians had decided to change their approach to the Serbs. They summoned all Serbian ''župans'' to pay homage to Časlav, then had them arrested and taken to Preslav. Serbia was annexed as a Bulgarian province, expanding the country's border to Croatia, which was at its apogee and proved to be a dangerous neighbour. The annexation was a necessary move since the Serbs had proven to be unreliable allies and Simeon had grown wary of the inevitable pattern of war, bribery and defection.

Campaigns against the Byzantines (918–922)

After the threat from Serbia was eliminated in 917, Simeon personally led a campaign in the Theme of Hellas and penetrated deep to the south, reaching the

After the threat from Serbia was eliminated in 917, Simeon personally led a campaign in the Theme of Hellas and penetrated deep to the south, reaching the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth (Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word "isthmus" comes from the Ancie ...

. Although many people fled to the island of Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poi ...

and the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

peninsula, the Bulgarians took many captives and forced the population to pay taxes to the Bulgarian state. The capital of Hellas, Thebes, was seized and its fortifications destroyed. A noteworthy episode of that campaign was described in the manual on warfare '' Strategikon'' by the 11th-century writer Kekaumenos Kekaumenos ( el, Κεκαυμένος) is the family name of the otherwise unidentified Byzantine author of the '' Strategikon'', a manual on military and household affairs composed c. 1078. He was apparently of Georgian-Armenian origin and the gra ...

. After fruitlessly besieging a populous city in Hellas, Simeon employed a ''ruse de guerre

The French , sometimes literally translated as ruse of war, is a non-uniform term; generally what is understood by "ruse of war" can be separated into two groups. The first classifies the phrase purely as an act of military deception against one' ...

'' by sending brave and resourceful men into the city to discover weaknesses in its defences. They discovered that the gates were held high above the ground on hinges. After receiving their report, Simeon sent five men into the city with axes to eliminate the guards, break the hinges, and open the gates for the Bulgarian army. After the gates were opened, the Bulgarian army moved in and occupied the city without bloodshed.

In the spring of 919, the military setbacks suffered by the Byzantines the previous two years triggered another change in Byzantine rule when Admiral Romanos Lekapenos forced Zoe Karbonopsina back to a monastery and quickly rose to prominence. In April, Lekapenos' daughter

In the spring of 919, the military setbacks suffered by the Byzantines the previous two years triggered another change in Byzantine rule when Admiral Romanos Lekapenos forced Zoe Karbonopsina back to a monastery and quickly rose to prominence. In April, Lekapenos' daughter Helena Lekapene

Helena Lekapene ( grc-x-byzant, Ἑλένη Λεκαπηνή, translit=Lecapena) (c. 910 – 19 September 961) was the empress consort of Constantine VII, known to have acted as his political adviser and ''de facto'' co-regent. She was a daughter ...

married ConstantineVII, and Lekapenos assumed the title ''basileopator

( el, βασιλεοπάτωρ, , father of the mperor}) was one of the highest secular titles of the Byzantine Empire. It was an exceptional post (the 899 ''Kletorologion'' of Philotheos lists it as one of the 'special dignities', ), and con ...

''. In September, Lekapenos was named ''Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

'', and in December he was crowned senior emperor. This new development infuriated Simeon as he considered Romanos a usurper and felt insulted that a son of an Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

peasant had taken his own desired position. As so, Simeon rebuffed offers to become related with Romanos through a dynastic marriage and refused to negotiate for peace until Lekapenos stepped down.

In the autumn of 920, the Bulgarian army campaigned deep into Thrace, reaching the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

and setting up camp on the shore of the Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles s ...

Peninsula just across from the city of Lampsacus

Lampsacus (; grc, Λάμψακος, translit=Lampsakos) was an ancient Greek city strategically located on the eastern side of the Hellespont in the northern Troad. An inhabitant of Lampsacus was called a Lampsacene. The name has been transmit ...

in Asia Minor. These actions caused great concern to the Byzantine court because the Bulgarians could cut Constantinople off from the Aegean Sea if they were successful in securing Gallipoli and Lampsacus. Patriarch Mystikos attempted to sue for peace and proposed a meeting with Simeon in Mesembria but to no avail.

The following year, the Bulgarians marched to Katasyrtai near Constantinople. The Byzantines attempted to lure the Bulgarians to the north away from their capital by conducting a campaign to the town of Aquae Calidae, near modern Burgas

Burgas ( bg, Бургас, ), sometimes transliterated as ''Bourgas'', is the second largest city on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast in the region of Northern Thrace and the fourth-largest in Bulgaria after Sofia, Plovdiv, and Varna, with a popu ...

. The Byzantine commander Pothos Argyros sent a detachment under Michael, son of Moroleon, to monitor the movements of the Bulgarians. Michael's troops ultimately were discovered and ambushed by the Bulgarians. Although the Byzantines inflicted significant casualties on the Bulgarians, they were defeated. Michael was wounded and fled back to Constantinople where he died.

After the conflict at Aquae Calidae, additional Bulgarians forces led by Menikos and Kaukanos were sent south. They crossed the Strandzha mountains and ravaged the countryside around Constantinople, threatening the palaces around the Golden Horn. The Byzantines summoned a large army, including troops from the city garrison, the imperial guard, and sailors from the navy, commanded by Pothos Argyros and Admiral Alexios Mosele. In March 921, the opposing forces clashed in the battle of Pegae where the Byzantines were routed. Pothos Argyros barely escaped, and Alexios Mosele drowned while attempting to board a ship. In 922, the Bulgarians captured the town of Vizye and burned the palaces of Empress Theodora

Theodora is a given name of Greek origin, meaning "God's gift".

Theodora may also refer to:

Historical figures known as Theodora

Byzantine empresses

* Theodora (wife of Justinian I) ( 500 – 548), saint by the Orthodox Church

* Theodora o ...

near the Byzantine capital. Romanos tried to oppose them by dispatching troops under Saktikios. Saktikios attacked the Bulgarian camp while most soldiers were scattered to gather supplies. When the Bulgarian forces were reassembled and informed about the attack, they counter-attacked and defeated the Byzantines mortally wounding their commander.

Attempts for a Bulgarian–Arab alliance

By 922, although the Bulgarians controlled almost the entire Balkan peninsula, Simeon's main objective remained out of his reach. The Bulgarian monarch was aware that he needed a navy to conquer Constantinople. Simeon decided to turn to

By 922, although the Bulgarians controlled almost the entire Balkan peninsula, Simeon's main objective remained out of his reach. The Bulgarian monarch was aware that he needed a navy to conquer Constantinople. Simeon decided to turn to Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh/ʿUbayd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn (), 873 – 4 March 934, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdi Billah, was the founder of the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate, the only major Shi'a caliphate in Islamic history, and the ...

(r.909–934), founder and caliph of the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

. He ruled most of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and posed a constant threat to the Byzantine possessions in Southern Italy. Although in 914 both sides had concluded a peace treaty, since 918 the Fatimids had renewed attacks on the Italian coast. In 922, the Bulgarians clandestinely sent envoys via Zachlumia

Zachlumia or Zachumlia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Zahumlje, Захумље, ), also Hum, was a medieval principality located in the modern-day regions of Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia (today parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia ...

, the state of their ally Michael, to the caliph's capital al-Mahdiyyah

Mahdia ( ar, المهدية ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 62,189 inhabitants, south of Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

on the Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

n coast. SimeonI suggested a joint attack on Constantinople with the Bulgarians providing a large land army and the Arabs a navy. It was proposed that all spoils would be divided equally, the Bulgarians would keep Constantinople and the Fatimids would gain the Byzantine territories in Sicily and Southern Italy.

Al-Mahdi Billah accepted the proposal and sent back his own emissaries to conclude the agreement. On the way home the ship was captured by the Byzantines near the Calabrian coast, and the envoys of both countries were sent to Constantinople. When RomanosI learned about the secret negotiations, the Bulgarians were imprisoned, while the Arab envoys were allowed to return to Al-Mahdiyyah with rich gifts for the caliph. The Byzantines then sent their own embassy to North Africa to outbid SimeonI, and eventually the Fatimids agreed not to aid Bulgaria. Another attempt of SimeonI to ally with the Arabs was recorded by the historian al-Masudi

Al-Mas'udi ( ar, أَبُو ٱلْحَسَن عَلِيّ ٱبْن ٱلْحُسَيْن ٱبْن عَلِيّ ٱلْمَسْعُودِيّ, '; –956) was an Arab historian, geographer and traveler. He is sometimes referred to as the "Herodotu ...

in his book '' Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems''. An Arab expedition from the Abbasid Caliphate under Thamal al-Dulafi landed on the Aegean coast of Thrace, and the Bulgarians established contact with them and sent envoys in Tarsus. However, this attempt also failed to produce tangible results.

Later years

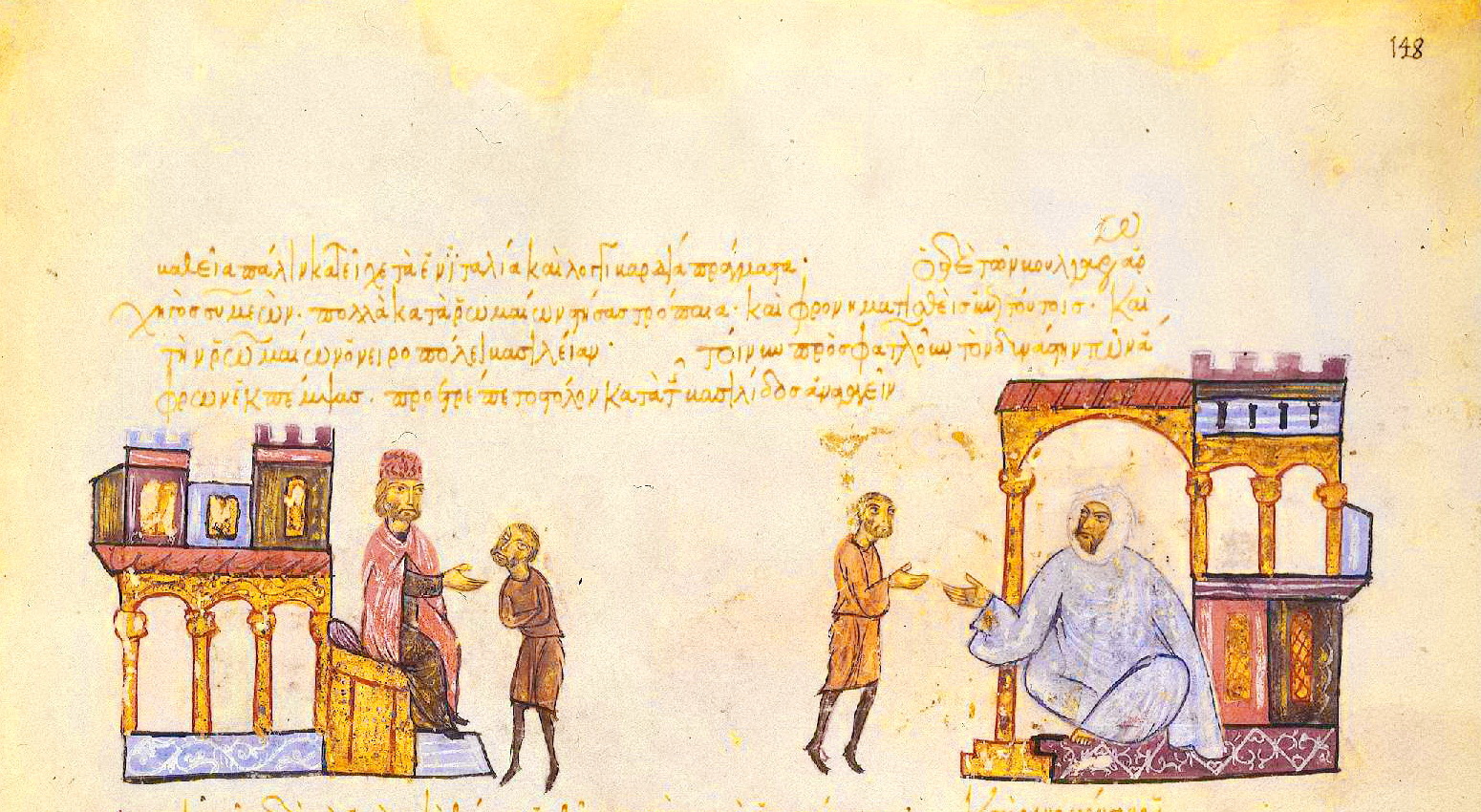

After the failure to secure an alliance with the Arabs, in September 923 or 924 SimeonI once again appeared in Byzantine Thrace. The Bulgarians pillaged the outskirts of Constantinople, burned the Church of St. Mary of the Spring and set up camp at the walls of Constantinople. SimeonI demanded a meeting with RomanosI in order to establish a temporary truce to deal with the Serbian threat. The Byzantines, eager to cease hostilities, agreed. Prior to the meeting at the suburb of Kosmidion, the Bulgarians took precautions and carefully inspected the specially prepared platformthey still remembered the failed Byzantine attempt to assassinate Khan

After the failure to secure an alliance with the Arabs, in September 923 or 924 SimeonI once again appeared in Byzantine Thrace. The Bulgarians pillaged the outskirts of Constantinople, burned the Church of St. Mary of the Spring and set up camp at the walls of Constantinople. SimeonI demanded a meeting with RomanosI in order to establish a temporary truce to deal with the Serbian threat. The Byzantines, eager to cease hostilities, agreed. Prior to the meeting at the suburb of Kosmidion, the Bulgarians took precautions and carefully inspected the specially prepared platformthey still remembered the failed Byzantine attempt to assassinate Khan Krum

Krum ( bg, Крум, el, Κροῦμος/Kroumos), often referred to as Krum the Fearsome ( bg, Крум Страшни) was the Khan of Bulgaria from sometime between 796 and 803 until his death in 814. During his reign the Bulgarian territo ...

(r.803–814) during negotiations at the same place a century earlier, in 813.

Romanos I arrived first; Simeon I appeared on a horse surrounded by elite soldiers who shouted in Greek "Glory to Simeon, the Emperor". According to the Byzantine chronicles, after the two monarchs had kissed, RomanosI demanded that SimeonI stop spilling Christian blood in an unnecessary war and delivered a small sermon to the ageing Bulgarian ruler asking how he could face God with all that blood on his hands. SimeonI had nothing to respond. However, historian Mark Whittow notes that those accounts were nothing but official Byzantine wishful thinking, composed after the event. The only hint of what really happened was an allegoric story that at the moment the meeting concluded, two eagles were seen flying high in the sky, then they engaged and immediately separated, one headed northwards to Thrace, the other flying to Constantinople. This was seen as a bad omen representing the fates of the two rulers. The portent of two eagles is a rhetorical implication that in the meeting RomanosI recognized SimeonI's imperial title and his equal status to the emperor in Constantinople. However, RomanosI never ratified the agreement in SimeonI's lifetime, and the contradictions between the two sides remained unresolved. In a correspondence dated from 925, the Byzantine emperor criticized SimeonI for calling himself "Emperor of the Bulgarians and the Romans" and demanded the return of the conquered fortresses in Thrace.

In 926 the Bulgarians sent an army to invade the Kingdom of Croatia in order to secure their rear for a new offensive on Constantinople. SimeonI saw the Croatian state as a threat because king Tomislav (r.910–928) was a Byzantine ally and harboured his enemies. The Bulgarians marched into Croatian territory but suffered a complete defeat at the hands of the Croats. Though peace was quickly restored through Papal

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

mediation, SimeonI continued to prepare for an assault on the Byzantine capital. It was evident that the Bulgarian losses had not been significant because only a small portion of the whole army had been sent to fight the Croats. The Bulgarian monarch seemed secure in the belief that king Tomislav would honour the peace. However, like his predecessor Krum, SimeonI died in the midst of the preparations for an attack on Constantinople on 27May 927, aged sixty–three.

Peace treaty

Simeon I was succeeded by his second sonPeter I Peter I may refer to:

Religious hierarchs

* Saint Peter (c. 1 AD – c. 64–88 AD), a.k.a. Simon Peter, Simeon, or Simon, apostle of Jesus

* Pope Peter I of Alexandria (died 311), revered as a saint

* Peter I of Armenia (died 1058), Catholico ...

(r.927–969). At the beginning of PeterI's reign, the most influential person in the court was his maternal uncle, George Sursuvul, who served at first as a regent of the young monarch. Upon acceding to the throne, PeterI and George Sursuvul launched a campaign in Byzantine Thrace, razing the fortresses in the region that had been held until then by the Bulgarians. The raid was meant as a demonstration of power, and from a position of strength the Bulgarians proposed peace. Both sides sent delegations to Mesembria to discuss the preliminary terms. The negotiations continued in Constantinople until the final provisions were agreed upon. In November 927 PeterI himself arrived in the Byzantine capital and was received personally by RomanosI. In the Palace of Blachernae the two sides signed a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surre ...

, sealed by a marriage between the Bulgarian monarch and the granddaughter of RomanosI, Maria Lekapene

Irene Lekapene (born Maria; bg, Ирина Лакапина, el, Μαρία/Ειρήνη Λεκαπηνή, died ca. 966) was the Empress consort of Peter I of Bulgaria. She was а daughter of Christopher Lekapenos, son and co-emperor of Romanos ...

. On that occasion Maria was renamed Irene, meaning "peace". On 8October 927 PeterI and Irene married in a solemn ceremony in the Church of St.Mary of the Springthe same church that SimeonI had destroyed a few years earlier and that had been rebuilt.

By the terms of the treaty, the Byzantines officially recognized the imperial title of the Bulgarian monarchs but insisted on the formula that the emperor of the Bulgarians be considered a "spiritual son" of the Byzantine emperor. Despite the wording, the title of the Bulgarian rulers equalled that of their Byzantine counterparts. The

By the terms of the treaty, the Byzantines officially recognized the imperial title of the Bulgarian monarchs but insisted on the formula that the emperor of the Bulgarians be considered a "spiritual son" of the Byzantine emperor. Despite the wording, the title of the Bulgarian rulers equalled that of their Byzantine counterparts. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church ( bg, Българска православна църква, translit=Balgarska pravoslavna tsarkva), legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria ( bg, Българска патриаршия, links=no, translit=Balgarsk ...

was also recognized as an independent Patriarchate

Patriarchate ( grc, πατριαρχεῖον, ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, designating the office and jurisdiction of an ecclesiastical patriarch.

According to Christian tradition three patriarchates were est ...

, thus becoming the fifth autocephalous

Autocephaly (; from el, αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Ort ...

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

after the patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, and the first national Orthodox Church. The treaty further stipulated an exchange of prisoners and an annual tribute to be paid by the Byzantines to the Bulgarian Empire. The treaty restored the border approximately along the lines agreed in 904the Bulgarians returned most of SimeonI's conquests in Thrace, Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thess ...

and Hellas and retained firm control over most of Macedonia and the larger part of Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinric ...

. Thus, PeterI succeeded in obtaining all of his father's goals, except for Constantinople.

Aftermath

During the first years of his reign, PeterI faced revolts by two of his three brothers, John in 928 and Michael in 930, but both were quelled. During most of his subsequent rule until 965, PeterI presided over a Golden Age of the Bulgarian state in a period of political consolidation, economic expansion and cultural activity. A treatise of the contemporary Bulgarian priest and writer Cosmas the Priest describes a wealthy, book-owning and monastery-building Bulgarian elite, and the preserved material evidence from Preslav, Kostur and other locations suggests a wealthy and settled picture of 10th-century Bulgaria. The influence of the landed nobility and the higher clergy increased significantly at the expense of the personal privileges of the peasantry, causing friction in the society. Cosmas the Priest accused the Bulgarian abbots and bishops of greed, gluttony and neglect towards their flock. In that setting during the reign of PeterI aroseBogomilism

Bogomilism ( Bulgarian and Macedonian: ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic or dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Pe ...

a dualistic heretic sect

A sect is a subgroup of a religious, political, or philosophical belief system, usually an offshoot of a larger group. Although the term was originally a classification for religious separated groups, it can now refer to any organization that b ...

that in the subsequent decades and centuries spread to the Byzantine Empire, northern Italy and southern France (cf. Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Follo ...

). The strategic position of the Bulgarian Empire remained difficult. The country was ringed by aggressive neighboursthe Magyars to the north-west, the Pechenegs and the growing power of Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

to the north-east, and the Byzantine Empire to the south, which despite the peace proved to be an unreliable neighbour.

The peace treaty allowed the Byzantine Empire to concentrate its resources on the declining Abbasid Caliphate to the east. Under the talented general John Kourkouas

John Kourkouas ( gr, Ἰωάννης Κουρκούας, Ioannes Kourkouas, ), also transliterated as Kurkuas or Curcuas, was one of the most important generals of the Byzantine Empire. His success in battles against the Muslim states in the Ea ...

, the Byzantines reversed the course of the Byzantine–Arab wars winning impressive victories over the Muslims. By 944 they had raided the cities of Amida, Dara

Dara is a given name used for both males and females, with more than one origin. Dara is found in the Bible's Old Testament Books of Chronicles. Dara �רעwas a descendant of Judah (son of Jacob). (The Bible. 1 Chronicles 2:6). Dara (also know ...

and Nisibis

Nusaybin (; '; ar, نُصَيْبِيْن, translit=Nuṣaybīn; syr, ܢܨܝܒܝܢ, translit=Nṣībīn), historically known as Nisibis () or Nesbin, is a city in Mardin Province, Turkey. The population of the city is 83,832 as of 2009 and is ...

in the middle Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers''). Originating in Turkey, the Euph ...

and besieged Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city ('' polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroen ...

. The remarkable Byzantine successes continued under Nikephoros Phokas, who ruled as emperor between 963 and 969, with the reconquest of Crete in 961 and the recovery of some territories in Asia Minor. The growing Byzantine confidence and power spurred Nikephoros Phokas to refuse the payment of the annual tribute to Bulgaria in 965. This resulted in a Rus' invasion of Bulgaria in 968–971, which led to a temporary collapse of the Bulgarian state and a bitter 50-year Byzantine–Bulgarian war until the conquest of the Bulgarian Empire by the Byzantines in 1018.

See also

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Byzantine-Bulgarian war of 913-927 10th century in Bulgaria 910s in the Byzantine Empire 920s in the Byzantine Empire 910s conflicts 920s conflicts Byzantine–Bulgarian Wars Wars involving the First Bulgarian Empire Constantine VII