Burning Of Women In England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In England, burning was a legal punishment inflicted on women found guilty of

In England, burning was a legal punishment inflicted on women found guilty of

By the end of the 13th century, several offences against either one's lord, or one's king, were

By the end of the 13th century, several offences against either one's lord, or one's king, were

Public executions were normally attended by large crowds. For the killing in 1546 of Anne Askew, charged with heresy and tortured at the

Public executions were normally attended by large crowds. For the killing in 1546 of Anne Askew, charged with heresy and tortured at the  A pamphlet detailing the burning in April 1652 of Joan Peterson, the so-called Witch of Wapping, also describes the execution of Prudence Lee, found guilty of

A pamphlet detailing the burning in April 1652 of Joan Peterson, the so-called Witch of Wapping, also describes the execution of Prudence Lee, found guilty of

The burning in 1789 of Catherine Murphy, for coining, received practically no attention from the newspapers (perhaps owing to practical limitations on how much news they could publish across only four pages), but it may have been enacted by Sir Benjamin Hammett, a former sheriff of London. Hammett was also an MP, and in 1790 he introduced to Parliament a ''Bill for Altering the Sentence of Burning Women''. He denounced the punishment as "the savage remains of Norman policy" which "disgraced our statutes", as "the practice did the common law". He also highlighted how a sheriff who refused to carry out the sentence was liable to prosecution. William Wilberforce and Hammett were not the first men to attempt to end the burning of women. Almost 140 years earlier, during the

The burning in 1789 of Catherine Murphy, for coining, received practically no attention from the newspapers (perhaps owing to practical limitations on how much news they could publish across only four pages), but it may have been enacted by Sir Benjamin Hammett, a former sheriff of London. Hammett was also an MP, and in 1790 he introduced to Parliament a ''Bill for Altering the Sentence of Burning Women''. He denounced the punishment as "the savage remains of Norman policy" which "disgraced our statutes", as "the practice did the common law". He also highlighted how a sheriff who refused to carry out the sentence was liable to prosecution. William Wilberforce and Hammett were not the first men to attempt to end the burning of women. Almost 140 years earlier, during the

In England, burning was a legal punishment inflicted on women found guilty of

In England, burning was a legal punishment inflicted on women found guilty of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, petty treason

Petty treason or petit treason was an offence under the common law of England in which a person killed or otherwise violated the authority of a social superior, other than the king. In England and Wales, petty treason ceased to be a distinct offen ...

, and heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

. Over a period of several centuries, female convicts were publicly burnt at the stake, sometimes alive, for a range of activities including coining and mariticide

Mariticide (from Latin ''maritus'' "husband" + ''-cide'', from ''caedere'' "to cut, to kill") literally means the killing of one's own husband. It can refer to the act itself or the person who carries it out. It can also be used in the context o ...

.

While men guilty of heresy were also burned at the stake, those who committed high treason were instead hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

. The English jurist William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family in ...

supposed that the difference in sentencing, although "full as terrible to the sensation as the other", could be explained by the desire not to publicly expose a woman's body. Public executions were well-attended affairs, and contemporary reports detail the cries of women on the pyre as they were burned alive. It later became commonplace for the executioner to strangle the convict, and for the body to be burned post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, changing attitudes to such public displays prompted Sir Benjamin Hammett MP to denounce the practice in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

. His bill, by no means the first such attempt to end the public burning of women, led to the Treason Act 1790

The Treason Act 1790 (30 Geo 3 c 48) was an Act of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain which abolished burning at the stake as the penalty for women convicted of high treason, petty treason and abetting, procuring or counselling pet ...

, which abolished the sentence.

Crimes punishable by burning

Treason

By the end of the 13th century, several offences against either one's lord, or one's king, were

By the end of the 13th century, several offences against either one's lord, or one's king, were treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

able. High treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, defined as transgressions against the sovereign, was first codified during King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

's reign by the Treason Act 1351

The Treason Act 1351 is an Act of the Parliament of England which codified and curtailed the common law offence of treason. No new offences were created by the statute. It is one of the earliest English statutes still in force, although it ha ...

. It clarified exactly what crimes constituted treason, following earlier, somewhat "over zealous" interpretations of England's legal codes. For instance, high treason could be committed by anyone found to be compassing the king's death or counterfeiting his coin. High treason remained distinct though, from what became known as petty treason

Petty treason or petit treason was an offence under the common law of England in which a person killed or otherwise violated the authority of a social superior, other than the king. In England and Wales, petty treason ceased to be a distinct offen ...

: the killing of a lawful superior, such as a husband by his wife. Though 12th century contemporary authors made few attempts to differentiate between high treason and petty treason, enhanced punishments may indicate that the latter was treated more seriously than an ordinary felony.

As the most egregious offence an individual could commit, viewed as seriously as though the accused had personally attacked the monarch, high treason demanded the ultimate punishment. But whereas men guilty of this crime were hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

, women were drawn and burned. In his ''Commentaries on the Laws of England

The ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'' are an influential 18th-century treatise on the common law of England by Sir William Blackstone, originally published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford, 1765–1770. The work is divided into four volu ...

'' the 18th-century English jurist William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family in ...

noted that the sentence, "to be drawn to the gallows, and there to be burned alive", was "full as terrible to the sensation as the other". Blackstone wrote that women were burned rather than quartered as "the decency due to the sex forbids the exposing and publicly mangling their bodies". However, an observation by historian Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and an author on other topics whose major work was a history of France and its culture. His aphoristic style emphasized his anti-clerical republicanism.

In Michelet ...

, that "the first flame to rise consumed the clothes, revealing poor trembling nakedness", may, in the opinion of historian Vic Gatrell, suggest that this solution is "misconceived". In ''The Hanging Tree'', Gatrell concludes that the occasional live burial of women in Europe gave tacit acknowledgement to the possibility that a struggling, kicking female hanging from a noose could "elicit obscene fantasies" from watching males.

Heresy

Another law enforceable by public burning was '' De heretico comburendo'', introduced in 1401 during the reign of Henry IV. It allowed for the execution of persons of both sexes found guilty ofheresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

, thought to be "sacrilegious and dangerous to souls, but also seditious and treasonable." Bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or offic ...

s were empowered to arrest and imprison anyone suspected of offences related to heresy and, once convicted, send them to be burned "in the presence of the people in a lofty place". Although the act was repealed in 1533/34, it was revived over 20 years later at the request of Queen Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. ...

who, during the Marian persecutions

Protestants were executed in England under heresy laws during the reigns of Henry VIII (1509–1547) and Mary I (1553–1558). Radical Christians also were executed, though in much smaller numbers, during the reigns of Edward VI (1547–1553) ...

, made frequent use of the punishment it allowed.

''De heretico comburendo'' was repealed by the Act of Supremacy 1558, although that act allowed ecclesiastical commissions to deal with occasional instances of heresy. Persons declared guilty, such as Bartholomew Legate and Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman (1566 – 11 April 1612) was an English radical Anabaptist minister, executed at Lichfield on charges of heresy. He was the last person to be burned at the stake in England for heresy.

Life

Edward Wightman was born in 1566. He ...

, could still be burned under a writ of ''de heretico comburendo'' issued by the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the Common law#History, common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over ...

. The burning of heretics was finally ended by the Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Act 1677 which, although it allowed ecclesiastical courts to charge people with "atheism, blasphemy, heresy, schism, or other damnable doctrine or opinion", limited their power to excommunication.

Execution of the sentence

Public executions were normally attended by large crowds. For the killing in 1546 of Anne Askew, charged with heresy and tortured at the

Public executions were normally attended by large crowds. For the killing in 1546 of Anne Askew, charged with heresy and tortured at the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, a "Substantial Stage" was built to seat the various officials who presided over her burning. A witness to proceedings reported that Askew was so badly injured by her torture that she was unable to stand. Instead, "the dounge carte was holden up between ij sarjantes, perhaps sitting there in a cheare".

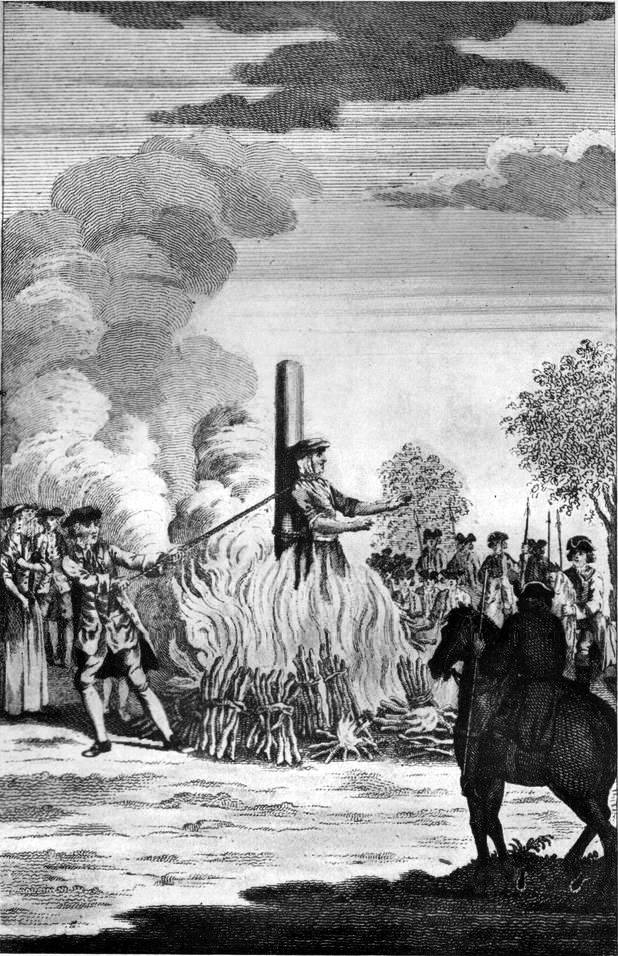

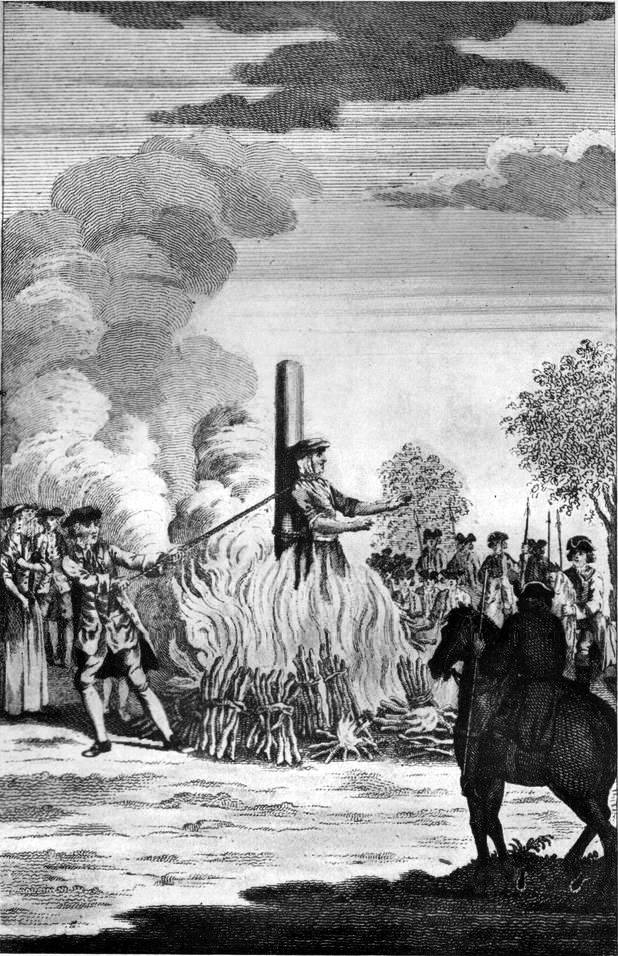

A pamphlet detailing the burning in April 1652 of Joan Peterson, the so-called Witch of Wapping, also describes the execution of Prudence Lee, found guilty of

A pamphlet detailing the burning in April 1652 of Joan Peterson, the so-called Witch of Wapping, also describes the execution of Prudence Lee, found guilty of mariticide

Mariticide (from Latin ''maritus'' "husband" + ''-cide'', from ''caedere'' "to cut, to kill") literally means the killing of one's own husband. It can refer to the act itself or the person who carries it out. It can also be used in the context o ...

. Lee was apparently brought on foot, between two sheriff's officers and dressed in a red waistcoat, to the place of execution in Smithfield. There she confessed to having "been a very lewd liver, and much given to cursing and swearing, for which the Lord being offended with her, had suffered her to be brought to that untimely end". She admitted to being jealous of and arguing with her husband, and stabbing him with a knife. The executioner put her in a pitch barrel, tied her to the stake, placed the fuel and faggots around her and set them alight. Lee was reported to have "desired all that were present to pray for her" and, feeling the flames, "shrike out terribly some five or six several times." Burning alive for murder was abolished in 1656, although burning for adultery remained. Thereafter, out of mercy, the condemned were often strangled before the flames took hold. Notable exceptions to this practice were the burnings in 1685 and 1726 of Elizabeth Gaunt, found guilty of high treason for her part in the Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and heir to the throne) James, Duke of York. The royal party went from Westminster to Newmarket to see horse races and were expected to make the r ...

, and Catherine Hayes, for petty treason. Hayes apparently "rent the air with her cries and lamentations" when the fire was lit too early, preventing the executioner from strangling her in time. She became the last woman in England to be burned alive.

The law also allowed for the hanging of children aged seven years or more. Mary Troke, "but sixteen years of age", was burned at Winchester

Winchester is a cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, at the western end of the South Downs National Park, on the River Itchen. It is south-west of Lon ...

in 1738 for poisoning her mistress. An unidentified 14-year-old girl imprisoned at Newgate was more fortunate. Found guilty in 1777 of being an accomplice to treason, for concealing whitewashed farthings on her person (at her master's request), she had been sentenced to burn. She was saved by the intervention of Thomas Thynne, 1st Marquess of Bath, who happened to be passing.

Changing attitudes

In 1786, Phoebe Harris and her accomplices were "indicted, for that they, on the 11th of February last, one piece of false, feigned, and counterfeit money and coin, to the likeness and similitude of the good, legal, and silver coin of this realm, called a shilling, falsely, deceitfully, feloniously, and traiterously did counterfeit and coin". Watched by a reported 20,000 people, she was led to the stake and stood on a stool, where a noose, attached to an iron bolt driven into the top of the stake, was placed around her neck. As prayers were read, the stool was taken away and over the course of several minutes, her feet kicking as her body convulsed, Harris choked to death. About 30 minutes later, faggots were placed around the stake, her body was chained into position, and subsequently burned for over two hours. Executions like this had once passed with little to no comment in the press. Historically, while fewer women than men were subjected to capital punishment, proportionately more were acquitted, found guilty of lesser charges, or pardoned if condemned. In centuries past, these women were judged by publications such as ''The Newgate Calendar

''The Newgate Calendar'', subtitled ''The Malefactors' Bloody Register'', was a popular work of improving literature in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Originally a monthly bulletin of executions, produced by the Keeper of Newgate Prison in Lo ...

'' to have succumbed to their own perversions, or to have been led astray. But while 18th and 19th-century women guilty of treasonable crimes were still seen as villains, increasingly, the cause of their descent was ascribed to villainous men. Those people concerned about the brutality inflicted on condemned women were, in Gatrell's opinion, "activated by the sense that even at their worst women were creatures to be pitied and protected from themselves, and perhaps revered, like all women from whom men were born." Commenting on Harris's execution, '' The Daily Universal Register'' claimed that the act reflected "a scandal upon the law", "a disgrace to the police" and "was not only inhuman, but shamefully indelicate and shocking". The newspaper asked "why should the law in this species of offence inflict a severer punishment upon a woman, than upon a man"?

Harris's fate prompted William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

to sponsor a bill which, if passed, would have abolished the practice. But as one of its proposals would have allowed the anatomical dissection of criminals other than murderers, the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

rejected it. Though sympathetic to reform of England's Bloody Code

The "Bloody Code" was a series of laws in England, Wales and Ireland in the 18th and early 19th centuries which mandated the death penalty for a wide range of crimes. It was not referred to as such in its own time, but the name was given later ...

, Lord Chief Justice Loughborough saw no need to change the law: "Although the punishment, as a spectacle, was rather attended with circumstances of horror, likely to make a more strong impression on the beholders than mere hanging, the effect was much the same, as in fact, no greater degree of personal pain was sustained, the criminal being always strangled before the flames were suffered to approach the body".

When on 25 June 1788 Margaret Sullivan was hanged and burned for coining, the same newspaper (by then called ''The Times'') wrote:

''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine' ...

'' addressed the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ir ...

:

Although in his objections to Wilberforce's 1786 bill Loughborough had noted that these women were dead long before they suffered the flames, many newspapers of the day made no such distinction. ''The Times'' incorrectly stated that Sullivan was burned alive, rhetoric which, in Dr Simon Devereaux's opinion, could be "rooted in the growing reverence for domesticated womanhood" that might have been expected at the time. As many objections may also have been raised by the perceived inequity of drawing and burning women for coining, whereas until 1783, when the halting of executions at Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

removed ritualistic dragging from public view, men were simply drawn and hanged. A widening gulf between the numbers of men and women whipped in London (during the 1790s, 393 men versus 47 women), which mirrors a similar decline in the sending of women to the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stocks ...

, may also indicate an imposition of commonly-held gender ideals on English penal practices.

Abolition

The burning in 1789 of Catherine Murphy, for coining, received practically no attention from the newspapers (perhaps owing to practical limitations on how much news they could publish across only four pages), but it may have been enacted by Sir Benjamin Hammett, a former sheriff of London. Hammett was also an MP, and in 1790 he introduced to Parliament a ''Bill for Altering the Sentence of Burning Women''. He denounced the punishment as "the savage remains of Norman policy" which "disgraced our statutes", as "the practice did the common law". He also highlighted how a sheriff who refused to carry out the sentence was liable to prosecution. William Wilberforce and Hammett were not the first men to attempt to end the burning of women. Almost 140 years earlier, during the

The burning in 1789 of Catherine Murphy, for coining, received practically no attention from the newspapers (perhaps owing to practical limitations on how much news they could publish across only four pages), but it may have been enacted by Sir Benjamin Hammett, a former sheriff of London. Hammett was also an MP, and in 1790 he introduced to Parliament a ''Bill for Altering the Sentence of Burning Women''. He denounced the punishment as "the savage remains of Norman policy" which "disgraced our statutes", as "the practice did the common law". He also highlighted how a sheriff who refused to carry out the sentence was liable to prosecution. William Wilberforce and Hammett were not the first men to attempt to end the burning of women. Almost 140 years earlier, during the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, a group of lawyers and laymen known as the Hale Commission

The Hale Commission was established by the Commonwealth of England on 30 January 1652 and led by Sir Matthew Hale to investigate law reform. Consisting of eight lawyers and thirteen laymen, the Commission met approximately three times a week and ...

(after its chairman Matthew Hale), was tasked by the House of Commons to take "into consideration what inconveniences there are in the law". Among the proposed reforms was the replacement of burning at the stake with hanging, but, mainly through the objections of various interested parties, none of the commission's proposals made it into law during the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rum ...

. Hammett was confident though. He believed that public opinion was on his side and that "the House would go with him in the cause of humanity". The change in execution venues, from Tyburn to Newgate

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to M ...

, also attracted criticism. Following Phoebe Harris's burning in 1786, as well as questioning the inequality of English law ''The Times'' complained about the location of the punishment and its effect on locals:

Another factor was the fate of Sophia Girton, found guilty of coining. Hammett's bill was introduced only four days before Girton's fate was to be decided, but a petition for her respite from burning, supported by another sheriff of London (either Thomas Baker or William Newman) and brought to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Bri ...

's notice by William Grenville

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, (25 October 175912 January 1834) was a British Pittite Tory politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1806 to 1807, but was a supporter of the Whigs for the duration of ...

, proved successful. Devereaux suggests that her impending fate lent weight to the eventual outcome of Hammett's bill, which was to abolish the burning of women for treason through the Treason Act 1790

The Treason Act 1790 (30 Geo 3 c 48) was an Act of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain which abolished burning at the stake as the penalty for women convicted of high treason, petty treason and abetting, procuring or counselling pet ...

. Catherine Murphy, who at her execution in 1789 was "drest in a clean striped gown, a white ribbon, and a black ribbon round her cap", was the last woman in England to be burned.

See also

*Arden of Faversham

''Arden of Faversham'' (original spelling: ''Arden of Feversham'') is an Elizabethan play, entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 3 April 1592, and printed later that same year by Edward White. It depicts the real-life murder ...

* Coventry Martyrs

* Pleading the belly

Pleading the belly was a process available at English common law, which permitted a woman in the later stages of pregnancy to receive a reprieve of her death sentence until after she bore her child. The plea was available at least as early as 138 ...

References

Footnotes Notes Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refend Death of women Execution methods English criminal law Medieval English law Women in England