British Fascists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The British Fascists was the first political organisation in the

The organisation was formed on 6 May 1923 by Rotha Lintorn-Orman in the aftermath of

The organisation was formed on 6 May 1923 by Rotha Lintorn-Orman in the aftermath of

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

to claim the label of fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

, although the group had little ideological unity apart from anti-socialism

Criticism of socialism (also known as anti-socialism) is any critique of socialist models of economic organization and their feasibility as well as the political and social implications of adopting such a system. Some critiques are not directe ...

for much of its existence, and was strongly associated with conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

. William Joyce, Neil Francis Hawkins, Maxwell Knight

Charles Henry Maxwell Knight OBE, known as Maxwell Knight, (9 July 1900 – 27 January 1968) was a British spymaster, naturalist and broadcaster, reputedly a model for the James Bond character "M". He played major roles in surveillance of an e ...

and Arnold Leese

Arnold Spencer Leese (16 November 1878 – 18 January 1956) was a British fascist politician. Leese was initially prominent as a veterinary expert on camels. A virulent anti-Semite, he led his own fascist movement, the Imperial Fascist League, ...

were amongst those to have passed through the movement as members and activists.

Structure and membership

The organisation was formed on 6 May 1923 by Rotha Lintorn-Orman in the aftermath of

The organisation was formed on 6 May 1923 by Rotha Lintorn-Orman in the aftermath of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 192 ...

, and originally operated under the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

-sounding name British Fascisti. Despite its name, the group had a poorly defined ideological basis at its beginning, being brought into being more by a fear of left-wing politics than a devotion to fascism. The ideals of the Boy Scout

A Scout (in some countries a Boy Scout, Girl Scout, or Pathfinder) is a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement. Because of the large age and development span, many Scouting associations have split ...

movement, with which many early members had also been involved in their younger days, also played a role, for the British Fascisti wished, according to General R. B. D. Blakeney, who was the BF President from 1924 to 1926, to "uphold the same lofty ideas of brotherhood, service and duty". At its formation, at least, the British Fascisti was positioned in the same right-wing conservative camp as the British Empire Union

The British Empire Union (BEU) was created in the United Kingdom during the First World War, in 1916, after changing its name from the Anti-German Union, which had been founded in April 1915. From December 1922 to summer 1952, it published a regula ...

and the Middle Class Union The Middle Classes Union was founded in February 1919 to safeguard property after the Reform Act 1918 had increased the number of working-class people eligible to vote. Sir George Ranken Askwith and Conservative MP and Irish landowner J. R. Pr ...

, and shared some members with these groups. The group had a complex structure, being presided over by both an Executive Council and Fascist Grand Council of nine men, with County and Area Commanders controlling districts below this. Districts contained a number of companies, which in turn were divided into troops with each troop made of three units and unit containing seven members under a Leader. A separate structure existed along similar lines for the group's sizeable female membership. The group became notorious for its inflated claims of membership (including the ridiculous claim that it had 200,000 members in 1926), although at its peak from 1925 to 1926 it had a membership of several thousand. It mustered 5,000 people for a London march on Empire Day in London in 1925.

Early membership largely came from high society, and included a number of women amongst its ranks, such as Dorothy, Viscountess Downe, Lady Sydenham of Combe, Baroness Zouche and Nesta Webster. Men from the aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

also joined, including Lord Glasgow, The Marquess of Ailesbury, Lord Ernest Hamilton, The Baron de Clifford, The Earl Temple of Stowe, Sir Arthur Henry Hardinge

Sir Arthur Henry Hardinge, (12 October 1859 – 27 December 1933), was a senior British diplomat.

Early life

Hardinge was born in London, the son of General Hon. Sir Arthur Edward Hardinge, (1828–1892), KCB, Commander of the Bombay Army and ...

and Leopold Canning, Lord Garvagh, who served as first President of the movement. High-ranking members of the armed forces also occupied leading roles in the group, with General Blakeney joined by the likes of General Sir Ormonde Winter

Brigadier-General Sir Ormonde de l'Épée Winter, KBE, CB, CMG, DSO (15 January 1875 – 13 February 1962), was a British Army officer and author who, after service in the First World War, was responsible for intelligence operations in Ire ...

, Rear-Admiral John Armstrong (the BF Vice President 1924–1926) and Colonel Sir Charles Rosdew Burn, who combined a role on the Grand Council of the British Fascisti with that of Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

MP for Torquay

Torquay ( ) is a seaside town in Devon, England, part of the unitary authority area of Torbay. It lies south of the county town of Exeter and east-north-east of Plymouth, on the north of Tor Bay, adjoining the neighbouring town of Paig ...

. Admirals Sir Edmund Fremantle

Admiral The Honourable Sir Edmund Robert Fremantle (16 June 1836 – 10 February 1929) was a Royal Navy officer who served as Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth (at the time, and from 1845 to 1900, formally known as Commander-in-Chief, Devonport).

Na ...

and Sir Reginald Tupper

Admiral Sir Reginald Godfrey Otway Tupper, (16 October 1859 – 5 March 1945) was a Royal Navy officer active during the late Victorian period and the First World War.

Early life and career

Reginald Tupper was born on 16 October 1859, the son o ...

, Brigadier-Generals Julian Tyndale-Biscoe and Roland Erskine-Tulloch, Rear Admiral William Ernest Russell Martin (BF's paymaster), Major-Generals James Spens, Thomas Pilcher and Colonel Daniel Burges

Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Burges, Victoria Cross, VC, Distinguished Service Order, DSO (1 July 1873 – 24 October 1946) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy ...

were also members. Serving military personnel were eventually banned from joining the group by the Army Council however.

At a more rank-and-file level, the group attracted a membership of middle- and working-class young men who spent much of their time in violent confrontations with similar men involved in the Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

; William Joyce was typical of this sort of low-level member. This domination by disgruntled members of the peerage and high-ranking officers meant that certain concerns not normally associated with the demands of fascism, such as anger at the decline of the large landowning agricultural sector, high levels of estate taxation and death duties, and the dearth of high-ranking civilian occupations considered suitable for the status of officers, were a central feature of the political concerns advanced by the British Fascisti. Other officials included Sir Michael Bruce, Arnold Leese

Arnold Spencer Leese (16 November 1878 – 18 January 1956) was a British fascist politician. Leese was initially prominent as a veterinary expert on camels. A virulent anti-Semite, he led his own fascist movement, the Imperial Fascist League, ...

, England cricket manager Sir Frederick Toone

Sir Frederick Charles Toone (25 June 1868 - ) was a cricket administrator, who in 1929 became the second man ever to be knighted for cricket-related activities. Unusually for a man who achieved such eminence in the game, he never played cricket ...

, England cricket captain Arthur Gilligan

Arthur Edward Robert Gilligan (23 December 1894 – 5 September 1976) was an English first-class cricketer who captained the England cricket team nine times in 1924 and 1925, winning four Test matches, losing four and drawing one. In fi ...

, John Baker White MP and Patrick Hannon

Sir Patrick Joseph Henry Hannon FRGS FRSA (1874 - 10 January 1963) was an Irish-born Conservative and Unionist Party politician, industrialist and agriculturalist. “one of parliaments most colourful characters”. He served as Member of Parl ...

MP.

Early development

The party confined itself to stewarding Conservative Party meetings andcanvassing

Canvassing is the systematic initiation of direct contact with individuals, commonly used during political campaigns. Canvassing can be done for many reasons: political campaigning, grassroots fundraising, community awareness, membership driv ...

for the party. In particular it campaigned vigorously on behalf of Oliver Locker-Lampson, whose "Keep Out the Reds" campaign slogan struck a chord with the group's strong anti-communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

. The group also indulged in a series of high-profile stunts, many of which were more in the vein of elaborate practical jokes than genuine subversion. In one such example, five British Fascisti forcibly removed Harry Pollitt from a train to Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, where he was due to address a National Minority Movement event, and attempted to bundle him on to a different train. The five members arrested for the event insisted that they had intended to send Pollitt on a weekend break and even claimed that he had taken £5 in expenses they offered him for that purpose. One of the group's few policies was a call for a reduction in income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Ta ...

so that the well-off could hire more servants and so reduce unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refe ...

.

The group changed its name in 1924 from ''British Fascisti'' to ''British Fascists'', in an attempt to distance itself from the Italian associations, although this move helped to bring about a split in the group with a more ideologically fascist group, the National Fascisti

The National Fascisti (NF), renamed British National Fascists (BNF) in July 1926, were a splinter group from the British Fascisti formed in 1924. In the early days of the British Fascisti the movement lacked any real policy or direction and so th ...

, going its own way. The group's patriotism had been questioned because of the Italian spelling of the name, while accusations were also made that it was in the pay of the Italian government. Placing emphasis on its support for the establishment, it even wrote to Labour Party Home Secretary Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of t ...

in 1924 telling him that the group was at his disposal if he wished to deploy them against picket lines during industrial unrest, an offer to which Henderson did not respond. Blakeney had replaced Canning as President that same year, with Canning claiming that he lived too far from London to be politically influential enough. London was the group's major base of operation. In December 1925 an attempt to organise a meeting in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

was broken up by communists, and the BF abandoned its attempts to set up in the city as a result.

Despite its close association with elements of the Conservative Party, the British Fascists did occasionally put up candidates in local elections. In 1924 two of its candidates in the municipal elections in Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven District of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed ...

, Arnold Leese

Arnold Spencer Leese (16 November 1878 – 18 January 1956) was a British fascist politician. Leese was initially prominent as a veterinary expert on camels. A virulent anti-Semite, he led his own fascist movement, the Imperial Fascist League, ...

and Henry Simpson, managed to secure election to the local council. Simpson would retain his seat in 1927 although by that stage both he and Leese had broken from the British Fascists.

General Strike

The British Fascists began to take on a more prominent role in the run-up to the General Strike of 1926, as it became clear that their propaganda predicting such an outcome was about to come true. They were, however, not permitted to join theOrganisation for the Maintenance of Supplies

The Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies was a British right-wing movement, established in 1925 to provide volunteers in the event of a general strike. During the General Strike of 1926, it was taken over by the government to provide vital ...

(OMS), a group established by the government and chaired by Lord Hardinge to mobilise a non-striking workforce in the event of general strike, without first relinquishing any explicit attachment to fascism, as the government insisted for the group to remain non-ideological. The structure of the OMS was actually based on that of the British Fascists, but the government was unwilling to rely on the British Fascists because of what they saw as the group's unorthodox nature and its reliance on funding from Rotha Lintorn-Orman (who had garnered a reputation for high living) and so excluded it as a group from the OMS. As a result, a further split occurred, as a number of members, calling themselves Loyalists and led by former BF President Brigadier-General Blakeney, did just that. In the event, the British Fascists formed their own Q Divisions, which took on much of the same work as the OMS during the strike, albeit without having any official government recognition.

The strike severely damaged the party as it failed to precipitate the "Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

Revolution", which Lintorn-Orman had set the party up to fight. In fact, the strike was largely peaceful and restrained, and fears of future outbreaks were quelled somewhat by the passing of the Trades Disputes Act. Many of its most prominent members and supporters also drifted away from the group in the aftermath of the strike. The party journal, initially called ''Fascist Bulletin'' before changing its name to ''British Lion'', went from a weekly to a monthly, and the loss of a number of key leaders and the erratic leadership of Lintorn-Orman, who was battling alcoholism, brought about a decline of activity. The group also became ravaged by factionalism, with one group following Lady Downe and the old ways of the British Fascists, and another centred around James Strachey Barnes and Sir Harold Elsdale Goad advocating full commitment to a proper fascist ideology.

Decline

Having been hit hard by the split from the General Strike, the British Fascists attempted to move gradually towards a more defined fascism, starting in 1927 by adopting a blue shirt and beret uniform in the style of similar movements in Europe. That same year they attempted to organise aRemembrance Day

Remembrance Day (also known as Poppy Day owing to the tradition of wearing a remembrance poppy) is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth member states since the end of the First World War to honour armed forces members who have died in ...

parade past Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

where they requested the King should salute them from the balcony but the requests were rejected and the parade did not take place. The progress towards fascism did not however come quickly enough for Arnold Leese who in 1928 split from the group, which he denounced as "conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

with knobs on", to establish his own Imperial Fascist League

The Imperial Fascist League (IFL) was a British fascist political movement founded by Arnold Leese in 1929 after he broke away from the British Fascists. It included a blackshirted paramilitary arm called the Fascists Legion, modelled after the ...

(IFL), a much more hard-line group which emphasised anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Before long, however, the British Fascists began to advocate a more authoritarian government in which the monarch would take a leading role in government, as well as advocating the establishment of a Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

-style corporate state. These policy changes were made possible by the departure of Blakeney, who was committed to representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represe ...

and whose main economic opinion was opposition to the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

. Even without Blakeney they retained some of their earlier Conservative-linked views, such as loyalty to the king, anti-trade union legislation, free trade within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and a general preference for the rural, although these were bolstered by fascist-influenced policies such as limiting the franchise, gradual purification of the "English race" and stringent restrictions on immigration and the activities of immigrants admitted to Britain. However, as Martin Pugh has pointed out the British Fascists actively encouraged comparisons with the Conservative Party, feeling that it would add a sense of legitimacy and Britishness to their activities, particularly as they faced harsh criticism from not only the left but also some Tories for their increasingly paramilitary structure. Nonetheless some Tories were close to the group, with Charles Burn sitting on the Grand Council and support being lent by the likes of Patrick Hannon

Sir Patrick Joseph Henry Hannon FRGS FRSA (1874 - 10 January 1963) was an Irish-born Conservative and Unionist Party politician, industrialist and agriculturalist. “one of parliaments most colourful characters”. He served as Member of Parl ...

, Robert Tatton Bower

Commander Robert Tatton Bower (9 June 1894 – 5 July 1975) was a Royal Navy officer and a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom.

Early life

Bower was the only son- with two sisters- of Major Sir Robert Lister Bower, KBE, CMG, o ...

, Robert Burton-Chadwick and Alan Lennox-Boyd

Alan Tindal Lennox-Boyd, 1st Viscount Boyd of Merton, CH, PC, DL (18 November 1904 – 8 March 1983), was a British Conservative politician.

Background, education and military service

Lennox-Boyd was the son of Alan Walter Lennox-Boyd by his ...

. Indeed, in May 1925 Hannon even booked a room in the House of Commons to host an event for the British Fascists.

After 1931 the BF abandoned its attempts to form a distinctly British version of Fascism, and instead adopted the full programme of Mussolini and his National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

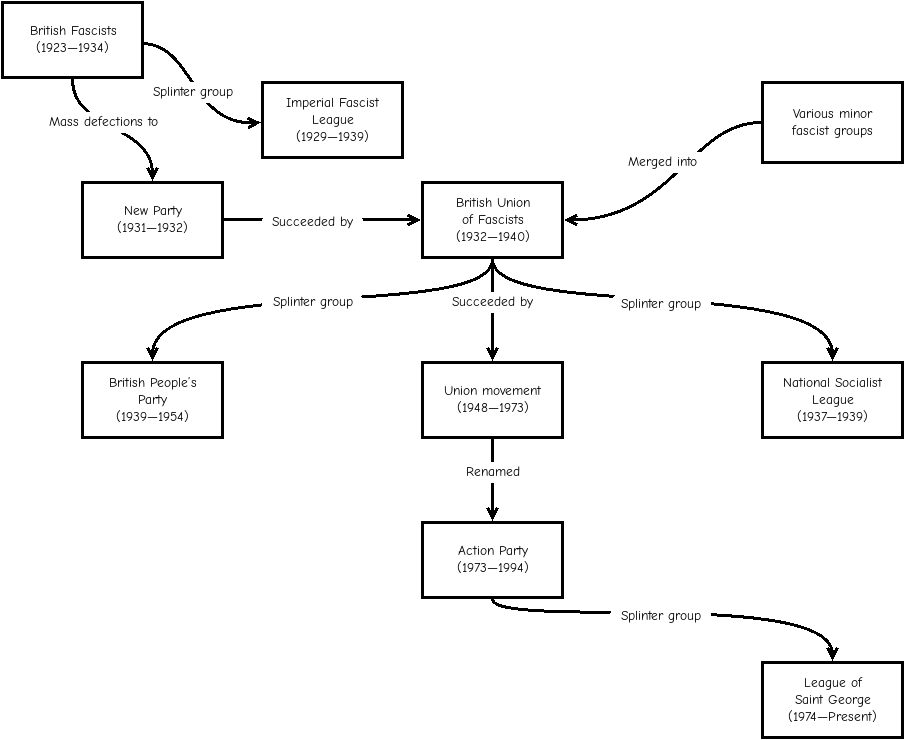

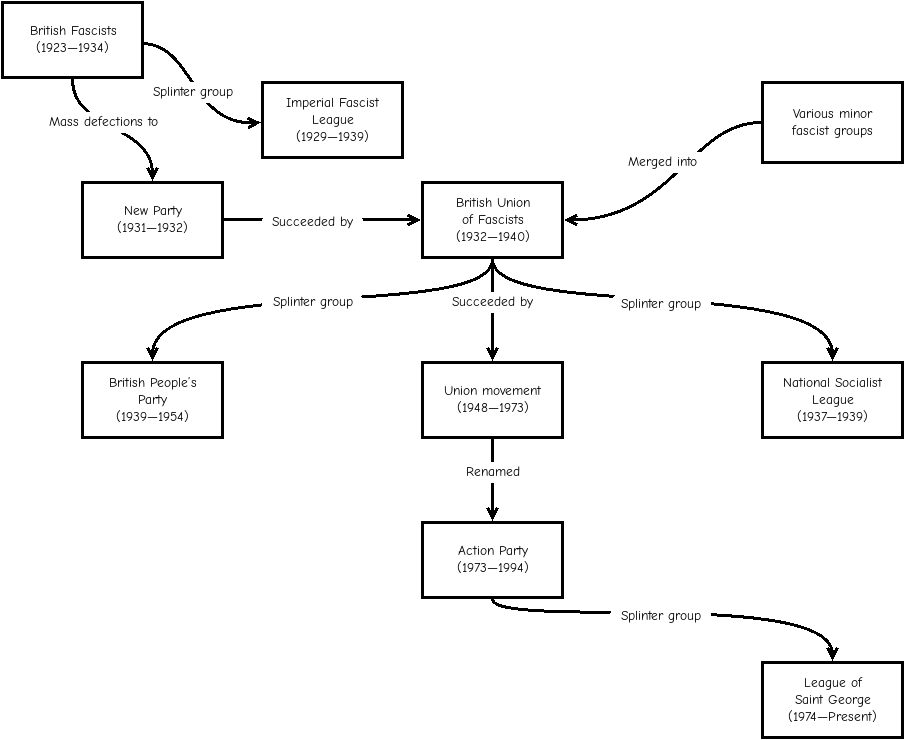

. The already weakened group split further in 1932 over the issue of a merger with Oswald Mosley's New Party. The proposal was accepted by Neil Francis Hawkins of the Headquarters Committee and his allies Lieutenant-Colonel H. W. Johnson and E. G. Mandeville Roe, although the female leadership turned the proposal down due to objections over serving under Mosley. Indeed, the British Fascists had protested against public meetings being addressed by Mosley as early as 1927, when they denounced the then Labour MP as a dangerous socialist. As a consequence Hawkins broke away and took much of the male membership of the BF with him; soon afterward, the New Party became the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

(BUF). Relations with the BUF were as a result frosty for the remainder of the group's life, and although Mosley dismissed the BF as "three old ladies and a couple of office boys", in 1933 a BUF fighting squad wrecked the BF's London offices after British Fascists members had heckled the BUF headquarters.

By this stage the BF membership had plummeted, with only a hardcore of members left. Various schemes were floated in an attempt to reinvigorate the movement, although none succeeded. Archibald Whitmore announced a plan to turn the British Fascists into an Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a u ...

group and successor to the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

, although after claiming that he was preparing to begin recruitment in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

, nothing came of this. The scheme had been led by Mrs D. G. Harnett, a close friend of Lintorn-Orman, who hoped the BF could profit from the emergence of prominent Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

as President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State

The president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State ( ga, Uachtarán ar Ard-Chomhairle Shaorstát Éireann) was the head of government or prime minister of the Irish Free State which existed from 1922 to 1937. He was the chairman of t ...

but the plan was scuppered when the policies of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

towards Northern Ireland largely remained the same under de Valera. A small group did exist in the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

, claiming to have a thousand members, although in fact having no more than 25 active in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

under H. R. Ledbeater. Favouring reunification with the UK, the group was involved in sending anti-Semitic leaflets to prominent Jews such as Robert Briscoe. It sought a merger with the right-wing Army Comrades Association, but this was rejected by Eoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish military commander, police commissioner and politician. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a prominent figure i ...

due to its pro-British stance.John M. Regan, ''The Irish Counter-Revolution 1921-1936'', Gill & Macmillan, 1999, pp. 334-335 Plans for a merger with the IFL did not get off the ground and plans for a merger with Graham Seton Hutchison's National Workers Party were also abandoned when it became clear that, far from having the 20,000 members in Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market to ...

alone that Seton Hutchison claimed, the party was little more than a one-man show.

In a bid to reverse its decline the party adopted a strongly anti-semitic platform. Thurlow notes: "it was noticeable that the BF became increasingly anti-semitic in its death throes." In 1933 Lord and Lady Downe, as representatives of the British Fascists, entertained Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

envoy Gunther Schmidt-Lorenzen at their country estate and suggested to him that the Nazis should avoid any links with Mosley, whom Lady Downe accused of being in the pay of Jewish figures such as Baron Rothschild

Baron Rothschild, of Tring in the County of Hertfordshire, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1885 for Sir Nathan Rothschild, 2nd Baronet, a member of the Rothschild banking family. He was the first Jewish memb ...

and Sir Philip Sassoon. Fellow member Madame Arnaud repeated similar allegations about Mosley to another German official, Dr Margarete Gartner of the Economic Policy Association. However, by this stage Lintorn-Orman's mother had cut her off financially after hearing lurid tales of debauchery involving the female fascist leader, and so the group fell into debt until being declared bankrupt in 1934 when a Colonel Wilson called in a £500 loan. This effectively brought the British Fascists to a conclusion; Rotha Lintorn-Orman died the following year.

See also

*List of British fascist parties

Although Fascism in the United Kingdom never reached the heights of many of its historical European counterparts, British politics after the First World War saw the emergence of a number of fascist movements, none of which ever came to power.

Pr ...

References

* * * * * * Stocker, Paul. "Importing fascism: reappraising the British fascisti, 1923–1926" ''Contemporary British History'', September 2016, Vol. 30 No. 3, pp. 326–348 *Footnotes

{{Authority control Political parties established in 1923 Fascist parties in the United Kingdom Defunct political parties in the United Kingdom Political parties disestablished in 1934 1923 establishments in the United Kingdom Clothing in politics Anti-communist organizations Anti-communism in the United Kingdom