British Administration of Heligoland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small

Online ''Heiliges Land – Helgoland und seine früheren Namen''.

In: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.): ''Nomen et fraternitas. Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag'' (Supplementary volumes to the ''Reallexikon des Germanischen Altertums''). De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020238-0, p. 480. The discussion is complicated by a disagreement as to which of the listed names really refers to the island of Helgoland, and by a desire for the island to still been seen as holy today.

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times.

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times.

On 11 September 1807, during the

On 11 September 1807, during the  As related in ''

As related in ''

Under the

Under the

auf spurensuche-kreis-pinneberg.de On 3 December 1939, Heligoland was directly bombed by the

''1939 Dezember''

(Württemberg State Library, Stuttgart). Retrieved 4 July 2015. In three days in 1940, the

''Unter den Wellen Teil 3 – Britische U-Boote vor Helgoland''

. February 2013. Early in the war, the island was generally unaffected by bombing raids. Through the development of the

''Im Schutz der roten Felsen – Bunker auf Helgoland''

vom 19. April 2005, auf fr-online.de The bomb attacks rendered the island unsafe, and it was totally evacuated.

From 1945 to 1952 the uninhabited islands fell within the

From 1945 to 1952 the uninhabited islands fell within the

Heligoland, like the small exclave

Heligoland, like the small exclave

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. A part of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

state of Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sch ...

since 1890, the islands were historically possessions of Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, then became the possessions of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

from 1807 to 1890, and briefly managed as a war prize from 1945 to 1952.

The islands are located in the Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (german: Helgoländer Bucht) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends fro ...

(part of the German Bight

The German Bight (german: Deutsche Bucht; da, tyske bugt; nl, Duitse bocht; fry, Dútske bocht; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and ...

) in the southeastern corner of the North Sea and had a population of 1,127 at the end of 2016. They are the only German islands not in the vicinity of the mainland. They lie approximately by sea from Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is an independent town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven has ...

at the mouth of the River Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

. During a visit to the islands, August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann (, calling himself von Fallersleben, after his hometown; 2 April 179819 January 1874) was a German poet. He is best known for writing "Das Lied der Deutschen", whose third stanza is now the national anthem of Germany, an ...

wrote the lyrics to "", which became the national anthem of Germany.

In addition to German, the local population, who are ethnic Frisians

The Frisians are a Germanic ethnic group native to the coastal regions of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany, ...

, speak the Heligolandic

Heligolandic (''Halunder'') is the dialect of the North Frisian language spoken on the German island of Heligoland in the North Sea. It is spoken today by some 500 of the island's 1,650 inhabitants and is also taught in schools. Heligolandic is cl ...

dialect of the North Frisian language

North Frisian (''nordfriisk'') is a minority language of Germany, spoken by about 10,000 people in North Frisia. The language is part of the larger group of the West Germanic Frisian languages. The language comprises 10 dialects which are thems ...

called .

Name

The island had no distinct name before the 19th century. It was often referred to by variants of the High German ''Heiligland'' ('holy land') and once even as the island of the Holy Virgin Ursula.Theodor Siebs

Theodor Siebs (; 26 August 1862 – 28 May 1941) was a German linguist most remembered today as the author of '' Deutsche Bühnenaussprache'' ("German stage pronunciation"), published in 1898. The work was largely responsible for setting the stan ...

summarized the critical discussion of the name in the 19th century in 1909 with the thesis that, based on the Frisian self-designation of the Heligolanders as ''Halunder'', the island name meant 'high land' ( similar to Hallig

The ''Halligen'' (German, singular ''Hallig'', ) or the ''halliger'' (Danish, singular ''hallig'') are small islands without protective levee, dikes. They are variously pluralized in English as the Halligen, Halligs, Hallig islands, or Halligen isl ...

). In the following discussion by Jürgen Spanuth, Wolfgang Laur again proposed the original name of ''Heiligland''. The variant ''Helgoland'', which has appeared since the 16th century, is said to have been created by scholars who Latinized a North Frisian form ''Helgeland'', using it to refer to a legendary hero, Helgi

Helge or Helgi is a Scandinavian, German, and Dutch mostly male name.

The name is derived from Proto-Norse ''Hailaga'' with its original meaning being ''dedicated to the gods''. For its Slavic version, see Oleg. Its feminine equivalent is Olga. ...

.

''Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde,'' Vol. 14, Artikel ''Helgoland.'' Berlin 1999.

For example, in Heike Grahn-HoekOnline ''Heiliges Land – Helgoland und seine früheren Namen''.

In: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.): ''Nomen et fraternitas. Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag'' (Supplementary volumes to the ''Reallexikon des Germanischen Altertums''). De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020238-0, p. 480. The discussion is complicated by a disagreement as to which of the listed names really refers to the island of Helgoland, and by a desire for the island to still been seen as holy today.

Geography

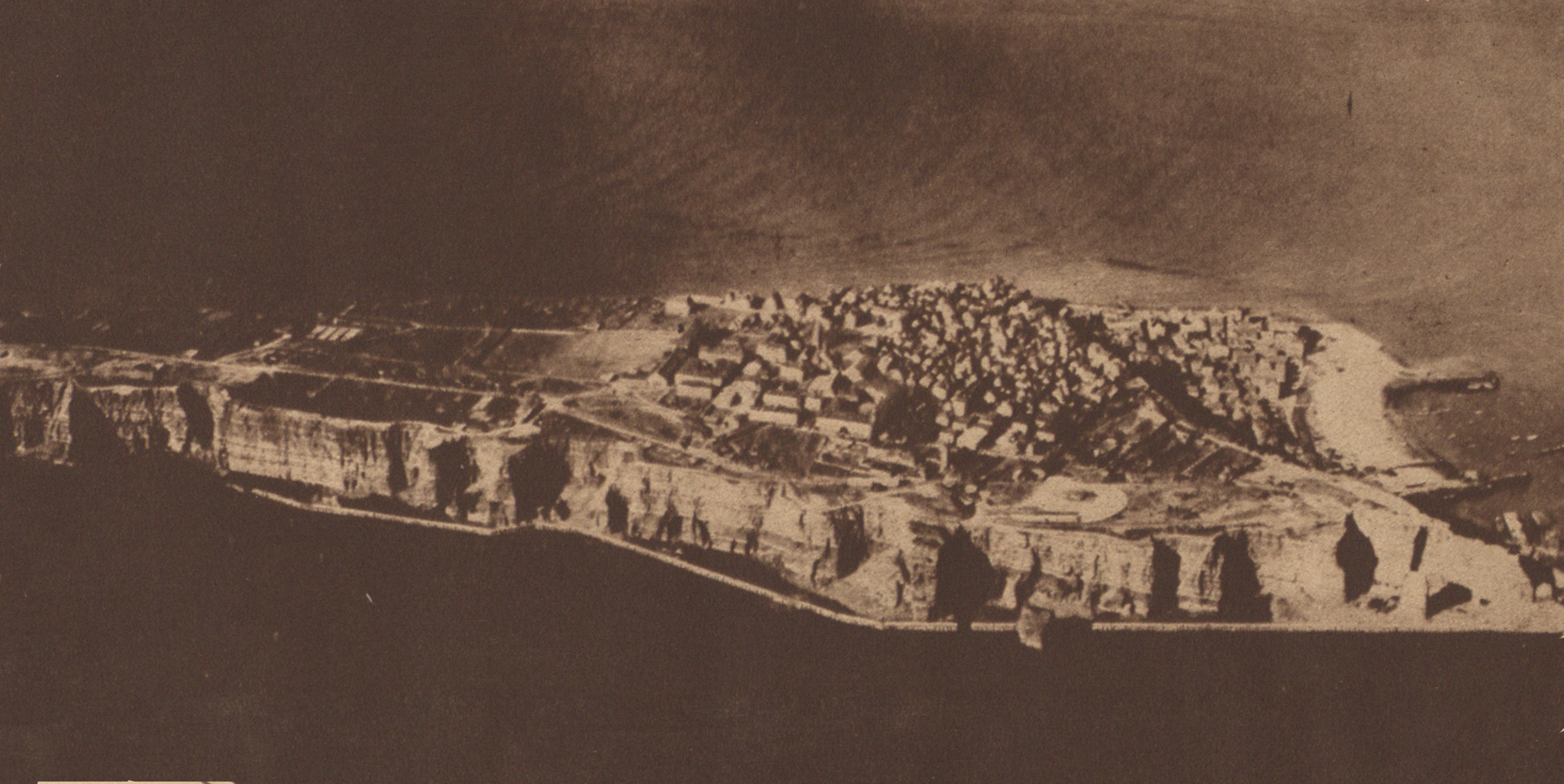

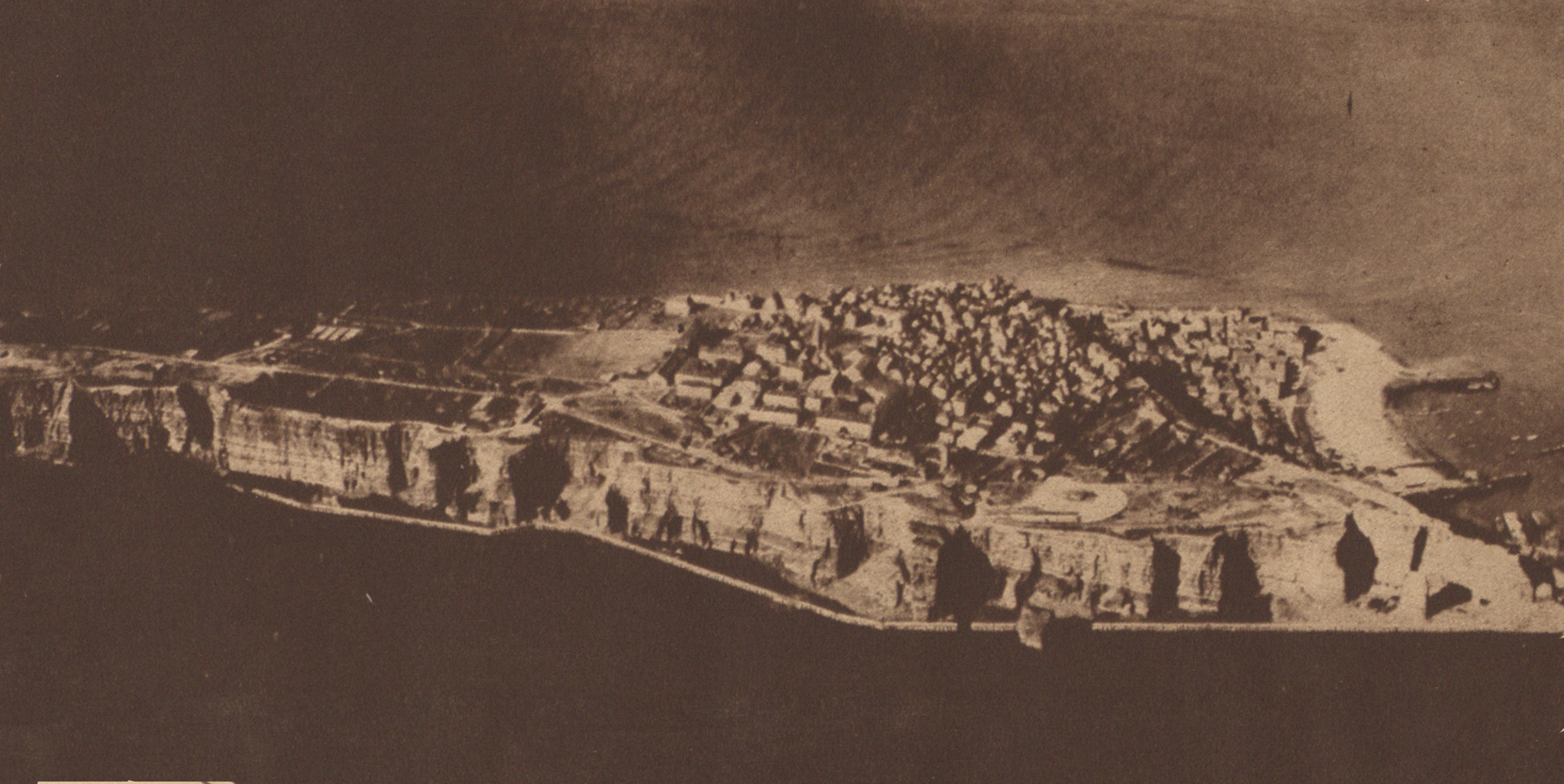

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's airfield

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publ ...

.

The main island is commonly divided into the ('Lower Land', Heligolandic: ) at sea level (to the right on the photograph, where the harbour is located), the ('Upper Land', Heligolandic: ) consisting of the plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ha ...

visible in the photographs, and the ('Middle Land') between them on one side of the island. The came into being in 1947 as a result of explosions detonated by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

(the so-called "Big Bang"; see below).

The main island also features small beaches in the north and the south and drops to the sea high in the north, west and southwest. In the latter, the ground continues to drop underwater to a depth of below sea level. Heligoland's most famous landmark is the ('Long Anna' or 'Tall Anna'), a free-standing rock column (or stack

Stack may refer to:

Places

* Stack Island, an island game reserve in Bass Strait, south-eastern Australia, in Tasmania’s Hunter Island Group

* Blue Stack Mountains, in Co. Donegal, Ireland

People

* Stack (surname) (including a list of people ...

), high, found northwest of the island proper.

The two islands were connected until 1720 when the natural connection was destroyed by a storm flood

A storm surge, storm flood, tidal surge, or storm tide is a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as cyclones. It is measured as the rise in water level above the no ...

. The highest point is on the main island, reaching above sea level.

Although culturally and geographically closer to North Frisia

North Frisia (; ; ) is the northernmost portion of Frisia, located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany between the rivers Eider and Wiedau. It also includes the North Frisian Islands and Heligoland. The region is traditionally inhabited by the North ...

in the German district of , the two islands are part of the district of Pinneberg

Pinneberg (; Northern Low Saxon: ''Pinnbarg'') is a town in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany. It is the capital of the Pinneberg (district), district of Pinneberg and has a population of about 43,500 inhabitants. Pinneb ...

in the state of Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sch ...

. The main island has a good harbour and is frequented mostly by sailing yachts.

History

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times.

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times. Flint tools

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

have been recovered from the bottom of the sea surrounding Heligoland. On the ''Oberland'', prehistoric burial mounds

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of Soil, earth and Rock (geology), stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a ...

were visible until the late 19th century, and excavations showed skeletons and artifacts. Moreover, prehistoric copper plates have been found underwater near the island; those plates were almost certainly made on the ''Oberland''.

In 697, Radbod, the last Frisian king, retreated to the then-single island after his defeat by the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

—or so it is written in the ''Life of Willebrord'' by Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

. By 1231, the island was listed as the property of the Danish king Valdemar II

Valdemar (28 June 1170 – 28 March 1241), later remembered as Valdemar the Victorious (), was the King of Denmark (being Valdemar II) from 1202 until his death in 1241.

Background

He was the second son of King Valdemar I of Denmark and Sophi ...

. Archaeological findings from the 12th to 14th centuries suggest that copper ore was processed on the island.

There is a general understanding that the name "Heligoland" means "Holy Land" (compare modern Dutch and German ''heilig Heilig may refer to:

*Heilig-Geist-Gymnasium, several schools

*Heilig (surname)

*Morton Heilig Morton Leonard Heilig (December 22, 1926 – May 14, 1997) was an American pioneer in virtual reality (VR) technology and a filmmaker. He applied his cin ...

'', "holy"). In the course of the centuries several alternative theories have been proposed to explain the name, from a Danish king Heligo to a Frisian word, ''hallig'', meaning "salt marsh island". The 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' suggests ''Hallaglun'', or ''Halligland'', i.e. "land of banks, which cover and uncover".

Traditional economic activities included fishing, hunting birds and seals, wrecking and—very important for many overseas powers—piloting overseas ships into the harbours of Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

cities such as Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

and Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

. In some periods Heligoland was an excellent base point for huge herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans, i ...

catches. Until 1714 ownership switched several times between Denmark-Norway and the Duchy of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

, with one period of control by Hamburg. In August 1714, it was conquered by Denmark-Norway, and it remained Danish until 1807.

19th century

On 11 September 1807, during the

On 11 September 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, brought to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

the despatches from Admiral Thomas Macnamara Russell

Thomas McNamara Russell (died 22 July 1824) was an admiral in the Royal Navy. Russell's naval career spanned the American Revolutionary War, French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic War.

Admiral Russell is best remembered for his command of a squ ...

announcing Heligoland's capitulation to the British. Heligoland became a centre of resistance and intrigue against Napoleon. Denmark then ceded Heligoland to George III of the United Kingdom

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until Acts of Union 1800, the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was ...

by the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel ( da, Kieltraktaten) or Peace of Kiel (Swedish and no, Kielfreden or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the ...

(14 January 1814). Thousands of Germans came to Britain and joined the King's German Legion

The King's German Legion (KGL; german: Des Königs Deutsche Legion, semantically erroneous obsolete German variations are , , ) was a British Army unit of mostly expatriated German personnel during the period 1803–16. The legion achieved th ...

via Heligoland.

The British annexation of Heligoland was ratified by the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

signed on 30 May 1814, as part of a number of territorial reallocations following the abdication of Napoleon as Emperor of the French.

The prime reason at the time for Britain's retention of a small and seemingly worthless acquisition was to restrict any future French naval aggression against the Scandinavian or German states. In the event, no effort was made during the period of British administration to make use of the islands for military purposes, partly for financial reasons but principally because the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

considered Heligoland to be too exposed as a forward base.

In 1826, Heligoland became a seaside spa and soon turned into a popular tourist resort for the European upper class. The island attracted artists and writers, especially from Germany and Austria who apparently enjoyed the comparatively liberal atmosphere, including Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, writer and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of '' Lied ...

and August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann (, calling himself von Fallersleben, after his hometown; 2 April 179819 January 1874) was a German poet. He is best known for writing "Das Lied der Deutschen", whose third stanza is now the national anthem of Germany, an ...

. More vitally it was a refuge for revolutionaries of the 1830s and the 1848 German revolution.

The Leisure Hour

''The Leisure Hour'' was a British general-interest periodical of the Victorian era which ran weekly from 1852 to 1905. It was the most successful of several popular magazines published by the Religious Tract Society, which produced Christian lite ...

'', it was "a land where there are no bankers, no lawyers, and no crime; where all gratuities are strictly forbidden, the landladies are all honest and the boatmen take no tips", while ''The English Illustrated Magazine

''The English Illustrated Magazine'' was a monthly publication that ran for 359 issues between October 1883 and August 1913. Features included travel, topography, and a large amount of fiction and were contributed by writers such as Thomas Hardy, ...

'' provided a description in the most glowing terms: "No one should go there who cannot be content with the charms of brilliant light, of ever-changing atmospheric effects, of a land free from the countless discomforts of a large and busy population, and of an air that tastes like draughts of life itself."

Britain ceded the islands to Germany in 1890 in the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty

The Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty (german: Helgoland-Sansibar-Vertrag; also known as the Anglo-German Agreement of 1890) was an agreement signed on 1 July 1890 between the German Empire and the United Kingdom.

The accord gave Germany control of ...

. The newly unified Germany was concerned about a foreign power controlling land from which it could command the western entrance to the militarily-important Kiel Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the N ...

, then under construction along with other naval installations in the area and thus traded for it. A "grandfathering

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

"/ optant approach prevented the inhabitants of the islands from forfeiting advantages because of this imposed change of status.

Heligoland has an important place in the history of the study of ornithology, and especially the understanding of migration. The book ''Heligoland, an Ornithological Observatory'' by Heinrich Gätke

Heinrich Gätke (born 19 May or 19 March 1814 in Pritzwalk – died 1 January 1897 in Heligoland) was a German ornithologist and artist.

Biography

The son of a baker, he was sent to study commerce in Berlin but became a painter. In 1837 he tra ...

, published in German in 1890 and in English in 1895, described an astonishing array of migrant birds on the island and was a major influence on future studies of bird migration

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a flyway, between breeding and wintering grounds. Many species of bird migrate. Migration carries high costs in predation and mortality, including from hunting by ...

.

In 1892, the Biological Station of Helgoland was founded by phycologist Paul Kuckuck, a student of Johannes Reinke

Johannes Reinke (February 3, 1849 – February 25, 1931) was a German botanist and philosopher who was a native of Ziethen, Lauenburg. He is remembered for his research of benthic marine algae.

Academic background

Reinke studied botany with h ...

(leading marine phycologist).

20th century

Under the

Under the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, the islands became a major naval base, and during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

the civilian population was evacuated to the mainland. The island was fortified with concrete gun emplacements along its cliffs similar to the Rock of Gibraltar

The Rock of Gibraltar (from the Arabic name Jabel-al-Tariq) is a monolithic limestone promontory located in the British territory of Gibraltar, near the southwestern tip of Europe on the Iberian Peninsula, and near the entrance to the Mediterr ...

. Island defences included 364 mounted guns including 142 disappearing gun

A disappearing gun, a gun mounted on a ''disappearing carriage'', is an obsolete type of artillery which enabled a gun to hide from direct fire and observation. The overwhelming majority of carriage designs enabled the gun to rotate back ...

s overlooking shipping channels defended with ten rows of naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

s. The first naval engagement of the war, the Battle of Heligoland Bight, was fought nearby in the first month of the war. The islanders returned in 1918, but during the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

era the naval base was reactivated.

Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a breakthrough paper. In the subsequent series ...

(1901–1976) first formulated the equation underlying his picture of quantum mechanics while on Heligoland in the 1920s. While a student of Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld, (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in atomic and quantum physics, and also educated and mentored many students for the new era of theoretica ...

at Munich in the early 1920s, Heisenberg first met the Danish physicist Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. B ...

. He and Bohr went for long hikes in the mountains and discussed the failure of existing theories to account for the new experimental results on the quantum structure of matter. Following these discussions, Heisenberg plunged into several months of intensive theoretical research but met with continual frustration. Finally, suffering from a severe attack of hay fever that his aspirin and cocaine treatment was failing to alleviate, he retreated to the treeless (and pollenless) island of Heligoland in the summer of 1925. There he conceived the basis of the quantum theory.

In 1937, construction began on a major reclamation project () intended to expand existing naval facilities and restore the island to its pre-1629 dimensions, restoring large areas which had been eroded by the sea. The project was largely abandoned after the start of World War II and was never completed.

World War II

The area was the setting of the aerial Battle of the Heligoland Bight in 1939, a result ofRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

bombing raids on Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

warships in the area. The waters surrounding the island were frequently mined by Allied aircraft.

Heligoland also had a military function as a sea fortress in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Completed and ready for use were the submarine bunker North Sea III, the coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of c ...

, an air-raid shelter system with extensive bunker tunnels and the airfield with the air force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

– (April to October 1943). Forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

of, among others, citizens of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

were used during the construction of military installations during World War II.''Lager russischer Offiziere und Soldaten, Helgoland Nordost''auf spurensuche-kreis-pinneberg.de On 3 December 1939, Heligoland was directly bombed by the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

for the first time. The attack, by twenty four Wellington bombers of 38, 115 and 149 squadrons of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

failed to destroy the German warships at anchor.Seekrieg''1939 Dezember''

(Württemberg State Library, Stuttgart). Retrieved 4 July 2015. In three days in 1940, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

lost three submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s in Heligoland: on 6 January, on 7 January and on 9 January.bremerhaven.de''Unter den Wellen Teil 3 – Britische U-Boote vor Helgoland''

. February 2013. Early in the war, the island was generally unaffected by bombing raids. Through the development of the

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

, the island had largely lost its strategic importance. The , temporarily used for defense against Allied bombing raids, was equipped with a rare variant of the Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the ''Luftwaffe's'' fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War ...

fighter originally designed for use on aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s.

Shortly before the war ended in 1945, Georg Braun and Erich Friedrichs succeeded in forming a resistance group. Shortly before they were to execute the plans, however, they were betrayed by two members of the group. About twenty men were arrested on 18 April 1945; fourteen of them were transported to Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is an independent town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven has ...

. After a short trial, five resisters were executed by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are us ...

at Cuxhaven-Sahlenburg on 21 April 1945 by the German authorities.Wolfgang Stelljes. ''Verräter kam aus den eigenen Reihen.'' In: ''Journal'' (weekend edition of ''Nordwest Zeitung''), Volume 70, No. 84 (1112 April 2015), s. 1.

To honour them, in April 2010 the Helgoland Museum installed six stumbling blocks on the roads of Heligoland. Their names are Erich P. J. Friedrichs, Georg E. Braun, Karl Fnouka, Kurt A. Pester, Martin O. Wachtel, and Heinrich Prüß.

With two waves of bombing raids on 18 and 19 April 1945, 1,000 Allied aircraft dropped about 7,000 bombs on the islands. The populace took shelter in air raid shelters. The German military suffered heavy casualties during the raids.Imke Zimmermann''Im Schutz der roten Felsen – Bunker auf Helgoland''

vom 19. April 2005, auf fr-online.de The bomb attacks rendered the island unsafe, and it was totally evacuated.

Explosion

British Occupation zone

The British occupation zone in Germany (German: ''Britische Besatzungszone Deutschlands'') was one of the Allied-occupied areas in Germany after World War II. The United Kingdom along with her Commonwealth were one of the three major Allied pow ...

and were used as a bombing range. On 18 April 1947, the Royal Navy detonated 6,700 tonnes of explosives ("Operation Big Bang

Operation Big Bang or British Bang was the explosive destruction of bunkers and other military installations on the island of Heligoland. The explosion used 7400 tons (6700 metric tons) of surplus World War II ammunition, which was placed in va ...

" or "British Bang") in an attempt to destroy the island entirely and remove it as a fleet base location for Germany. This resulted in one of the biggest single non-nuclear detonations in history. The blow shook the main island several miles down to its base, changing its shape (the was created).

Return of sovereignty to Germany

On 20 December 1950, two students and a professor fromHeidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

– René Leudesdorff, Georg von Hatzfeld and Hubertus zu Löwenstein – occupied the off-limits island and raised various German, European and local flags. The students were arrested by the soldiers present and brought back to Germany. The event started a movement to restore the islands to West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, which gained the support of the West German parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. On 1 March 1952, Heligoland was returned to German control, and the former inhabitants were allowed to return. The first of March is an official holiday on the island. The German authorities cleared a significant quantity of unexploded ordnance and rebuilt the houses before allowing its citizens to resettle there.

21st century

Heligoland, like the small exclave

Heligoland, like the small exclave Büsingen am Hochrhein

Büsingen am Hochrhein (, "Büsingen on the Upper Rhine"; Alemannic: ''Büesinge am Hochrhi''), commonly known as Büsingen, is a German municipality () in the south of Baden-Württemberg and an enclave entirely surrounded by the Swiss cantons ...

, is now a holiday resort and enjoys a tax-exempt status

Tax exemption is the reduction or removal of a liability to make a compulsory payment that would otherwise be imposed by a ruling power upon persons, property, income, or transactions. Tax-exempt status may provide complete relief from taxes, redu ...

, being part of Germany and the EU but excluded

{{Short pages monitor