Boyars of Wallachia and Moldavia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia were the

The boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia were the

After the Phanariote regime was instated in Moldavia (1711) and Wallachia (1716), many of the boyar class was made out of

After the Phanariote regime was instated in Moldavia (1711) and Wallachia (1716), many of the boyar class was made out of

Women in the Ottoman Balkans: Gender, Culture and History

2007 page 210-213 Many boyars used large sums of money for

The boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia were the

The boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia were the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

of the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

. The title was either inherited or granted by the Hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or " master".

Etymology and Slavic usage

In the Slavonic language, ''hospodar'' is usually applied to the master/owner of a house or other properties and also the head of a family. ...

, often together with an administrative function.Djuvara, p.131 The boyars held much of the political power in the principalities and, until the Phanariote era, they elected the Hospodar.

As such, until the 19th century, the system oscillated between an oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

and an autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

with the power concentrated in the hospodar's hands.Djuvara, p.135

Origins

During the Middle Ages, Romanians lived in autonomous communities called obște which mixed private andcommon ownership

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property.

Forms of common ownership exist in every econom ...

, employing an open field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

. The private ownership of land gained ground In the 14th and 15th centuries, leading to differences within the obște towards a stratification of the members of the community.Costăchel et al., p. 111

The name of the "boyars" (''boier'' in Romanian; the institution being called ''boierie'') was patented from the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, which had significant power and influence over Moldavia.

The creation of the feudal domain in which the landlords were known as boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

s, was mostly through ''danii'' ("donations") system: the hospodars gave away whole villages to military servants, usurping the right of property of the obște.Costăchel et al., p. 112 By the 16th century, the few remaining still-free villages were forcefully taken over by boyars,Costăchel et al., p. 113 while some people were forced to agree to become serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s (see Serfdom in Moldavia and Wallachia) due to hunger, invasions, high taxes, debts, which further deteriorated the economic standing of the free peasants.Costăchel et al., p. 114

Apart from the court boyars and the military elite, some boyars ("countryside boyars") arose from within the villages, when a leader of the obște (usually called ''knyaz

, or ( Old Church Slavonic: Кнѧзь) is a historical Slavic title, used both as a royal and noble title in different times of history and different ancient Slavic lands. It is usually translated into English as prince or duke, dependi ...

'') swore fidelity to the hospodar and becoming the landlord of the village.Costăchel et al., p. 177

Feudal era

The hospodar was considered the supreme ruler of the land and he received aland rent

In economics, economic rent is any payment (in the context of a market transaction) to the owner of a factor of production in excess of the cost needed to bring that factor into production. In classical economics, economic rent is any payment m ...

from the peasants, who also had to pay a rent to the boyar who owned the land.Costăchel et al., p. 174 The boyars were generally excepted from any taxes and rents to be paid to the hospodar. The boyars were entitled to a rent that was a percentage of the peasants' produce (initially one-tenth, hence its name, ''dijmă'') in addition to a number of days of unpaid labour (corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

, locally known as ''clacă'' or ''robotă'').

However, not all landlords who owned villages were boyars, a different class existed of landlords without a boyar title, called ''cneji'' or ''judeci'' in Wallachia and ''nemeși'' in Moldavia. They were however not tax-exempt like the boyars.Costăchel et al., p. 179 The upper boyars (known as ''vlastelin'' in Wallachia) had to supply the hospodar with a number of warriors proportional to the number of villages they owned.Costăchel et al., p. 189

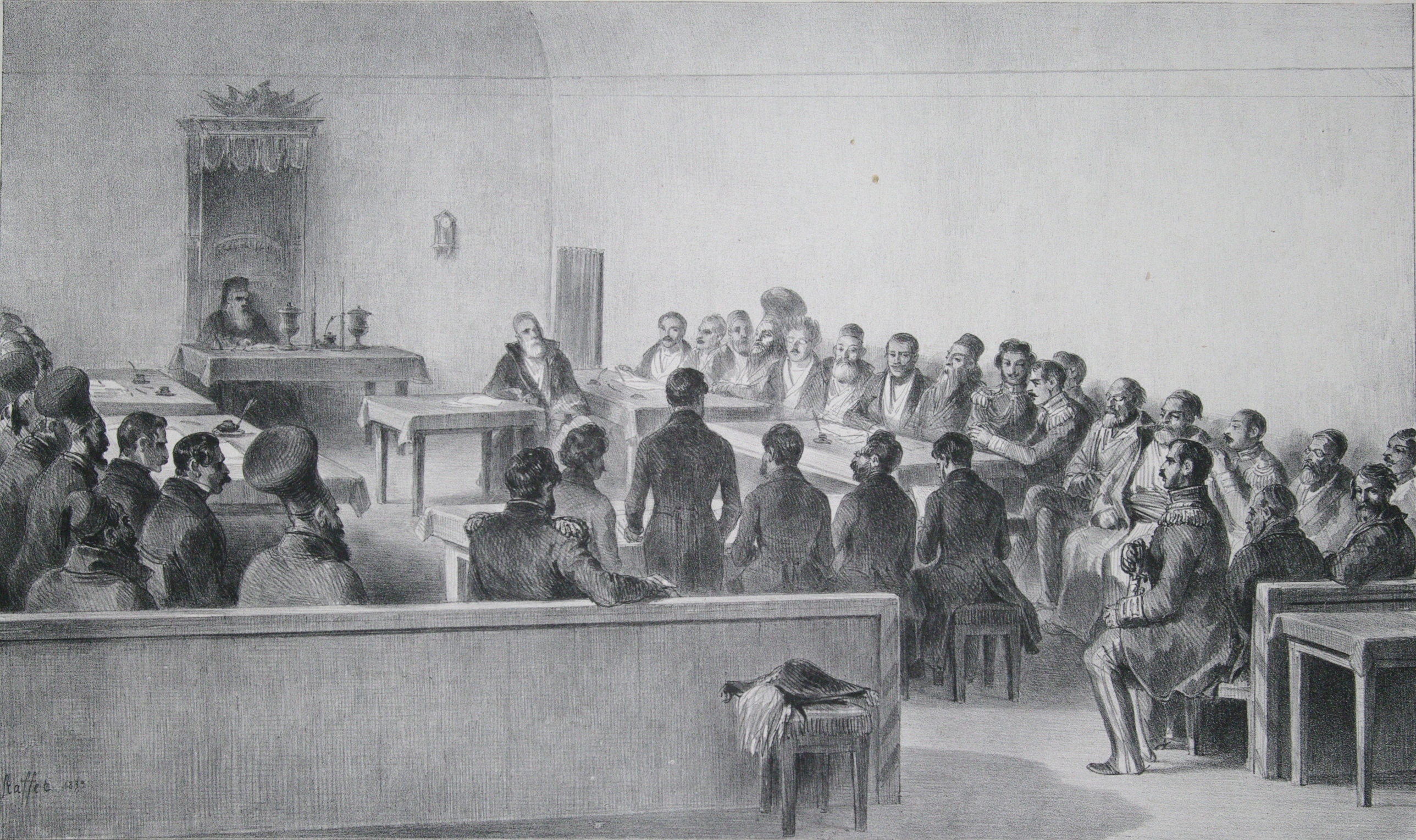

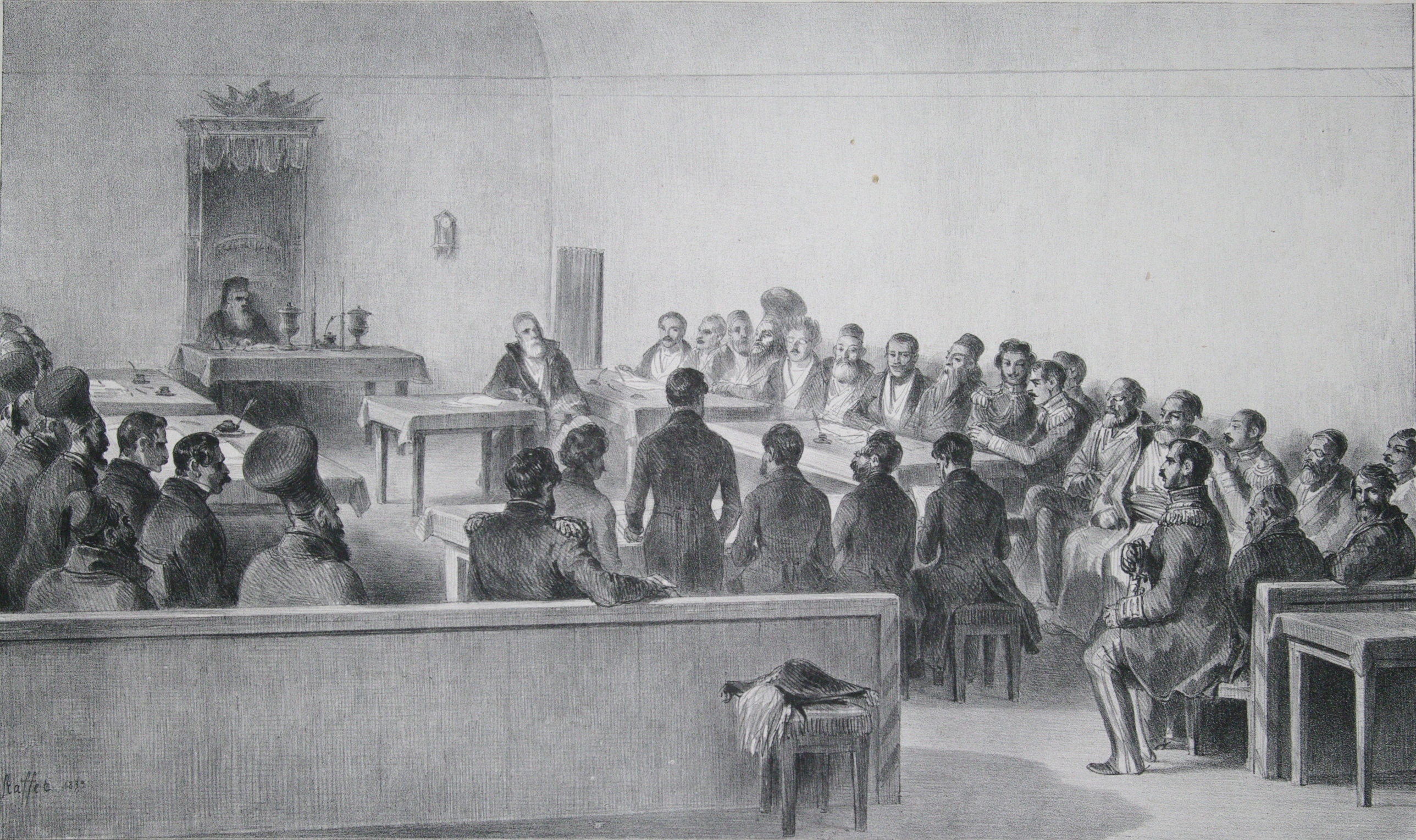

Some boyars were court officials, the office being called ''dregătorie'', while others were boyars without a function. Important offices at the court that were held by boyars included ''vistier'' (treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

), ''stolnic

''Stolnic'' was a ''boier'' (Romanian nobility) rank and the position at the court in the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. The title approximately corresponds to seneschal and is borrowed from the Slavic title ''stolnik'' (from ...

'' (pantler), ''vornic'' (concierge

A concierge () is an employee of a multi-tenant building, such as a hotel or apartment building, who receives guests. The concept has been applied more generally to other hospitality settings and to personal concierges who manage the errands of ...

) and ''logofăt'' (chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

).Costăchel et al., p. 184-185 While early the court officials were not important and often they were not even boyars, with time, boyars started to desire the functions, in order to participate in the government of the country, but also to get the incomes that were afferent to each function.Costăchel et al., p. 193

While the era is often called "feudal" in the Romanian historiography, there were some major differences between the status of the Western feudal lords and the status of the Romanian boyars.Djuvara, p.133 While a hierarchy existed in Wallachia and Moldavia just like in the West, the power balance was titled towards the hospodar, who had everyone as subjects and who had the power to demote even the richest boyar, to confiscate his wealth or even behead him. However, the power for the election of the hospodar was held by the great boyar families, who would form groups and alliances, often leading to disorder and instability.

Phanariote era

After the Phanariote regime was instated in Moldavia (1711) and Wallachia (1716), many of the boyar class was made out of

After the Phanariote regime was instated in Moldavia (1711) and Wallachia (1716), many of the boyar class was made out of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

Greeks who belonged to the Phanariote clients, who became officials and were assimilated to the boyar class or locals who bought their titles. When coming to Bucharest or Iași, the new Phanariote hospodars came with a Greek retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble, royal personage, or dignitary; a ''suite'' (French "what follows") of retainers.

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since circa 1375, stems from Old French ''retenue'', ...

who were given the most important official jobs; many of these Greeks married into local boyar families. In order to consolidate their position within the Wallachian and Moldavian boyar class, the officials were allowed to keep their boyar title after the end of their term.

The official functions, which traditionally were given for a year, were often bought with money as an investment, since the function would often give large incomes in return. While the official functions were often given to both Romanians and Greeks, there was an exception: throughout the Phanariote era, the treasurers were mostly local boyars because they were more competent in collecting taxes.Ionescu, p.64 When the descendants of a boyar were not able to obtain even the lowest function, they became "fallen boyars" (''mazili''), who nevertheless, kept some fiscal privileges.Djuvara, p.136

Many of the newly bestowed local boyars were wealthy merchants who paid in order to become boyars, in some cases they were even forced by the hospodar to become boyars (and thus pay the hospodar a sum).Ionescu, p.65 The princely courts of Bucharest and Iași kept title registers, which included a list of all the boyars (known as '' Arhondologia''). Since the hospodar wanted to maximize his income, it was in his interest to create as many boyars as possible (and receive money from each), leading to an inflation in the number of boyars.

The economic basis of the boyar's class was land ownership: by the 18th century, more than half of the land of Wallachia and Moldavia being owned by them. For instance, according to the 1803 Moldavian census, out of the 1711 villages and market towns, the boyars owned 927 of them. The process that began during the feudal era, of boyars seizing properties from the free peasants, continued and accelerated during this period.

The boyars wore costumes similar to those of the Turkish nobility, with the difference that instead of the turban

A turban (from Persian دولبند, ''dulband''; via Middle French ''turbant'') is a type of headwear based on cloth winding. Featuring many variations, it is worn as customary headwear by people of various cultures. Communities with promin ...

, most of them wore a very large Kalpak. Female members of the boyar class also wore Turkish inspired costume.Amila Buturovic & Irvin Cemil SchickWomen in the Ottoman Balkans: Gender, Culture and History

2007 page 210-213 Many boyars used large sums of money for

conspicuous consumption

In sociology and in economics, the term conspicuous consumption describes and explains the consumer practice of buying and using goods of a higher quality, price, or in greater quantity than practical. In 1899, the sociologist Thorstein Veblen c ...

, particularly luxurious clothing, but also carriages, jewelry and furniture. The luxury of the boyars' lives contrasted strongly not only with the squalor of the Romanian villages, but also with the general appearance of the capitals, this contrast striking the foreigners who visited the Principalities. In the first decade of the 19th-century, female members of the boyar class started to adopt Western fashion: in July 1806, the wife of the hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or " master".

Etymology and Slavic usage

In the Slavonic language, ''hospodar'' is usually applied to the master/owner of a house or other properties and also the head of a family. ...

in Iași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the second largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, it has traditionally ...

, Safta Ipsilanti, received the wife of the French consul dressed according to the French fashion. Male boyars, however, did not reform their costume to Western fashion until around the 1840s.

The opening towards Western Europe meant that the boyars adopted the Western mores and the luxury expenses increased. While the greater boyars were able to afford these expenses through the intensification of the exploitation of their domains (and the peasants working on them), many smaller boyars were ruined by them.Djuvara, p.146

Early modern

1848 Revolution

Modern Romania

Starting with the middle of the 19th century, the word "boyar" began to lose its meaning as a "noble" and to mean simply "large landowner". Cuza's Constitution (known as the ''Statut'') of 1864 deprived the boyars from the legal privileges and the ranks officially disappeared, but, through their wealth, they retained their economic and political influence,Hitchins, p.9 particularly through the electoral system ofcensus suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to ...

. Some of the lower boyars joined the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

involved in commerce and industry.

A number of 2000 large landowners held over 3 million hectares or about 38% of all arable land.Hitchins, p.158 Most of these boyars no longer took any part in managing their estates, but rather lived in Bucharest or in Western Europe (particularly France, Italy and Switzerland). They leased their estates for a fixed sum to ''arendași'' (leaseholders). Many of the boyars found themselves in financial difficulties; many of their estates had been mortgaged. The lack of interest in agriculture and their domains led to a dissolution of the boyar class.

Legacy

The movement surrounding the ''Sămănătorul

''Sămănătorul'' or ''Semănătorul'' (, Romanian for "The Sower") was a literary and political magazine published in Romania between 1901 and 1910. Founded by poets Alexandru Vlahuță and George Coșbuc, it is primarily remembered as a tribun ...

'' magazine lamented the disappearance of the boyar class, while not arguing for their return.Hitchins, p.68 Historian Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

saw the system not as a selfish exploitation of the peasants by the boyars, but rather as a rudimentary democracy.Hitchins, p.69 On the other side of the political spectrum, Marxist thinker Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea (born Solomon Katz; 1855, village of Slavyanka near Yekaterinoslav (modern Dnipro), then in Imperial Russia – 1920, Bucharest) was a Romanian Marxist theorist, politician, sociologist, literary critic, and ...

thought that the reforms didn't go far enough, arguing that the condition of the peasants was a ''neo-serfdom''.Hitchins, p.77

Notes

References

*V. Costăchel,P. P. Panaitescu

Petre P. Panaitescu (March 11, 1900 – November 14, 1967) was a Romanian literary historian. A native of Iași, he spent most of his adult life in the national capital Bucharest, where he rose to become a professor at University of Bucharest, ...

, A. Cazacu. (1957) ''Viața feudală în Țara Românească și Moldova (secolele XIV–XVI)'' ("Feudal life in the Romanian and Moldovan Land (14th–16th centuries)", Bucharest, Editura Științifică

*Ștefan Ionescu, ''Bucureștii în vremea fanarioților'' ("Bucharest in the Time of the Phanariotes"), Editura Dacia, Cluj, 1974.

*Neagu Djuvara

Neagu Bunea Djuvara (; 18 August 1916 – 25 January 2018) was a Romanian historian, essayist, philosopher, journalist, novelist, and diplomat.

Biography

Early life

A native of Bucharest, he was descended from an aristocratic Aromanian family ...

, ''Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne'', Humanitas, Bucharest, 2009.

*Keith Hitchins

Keith Arnold Hitchins (April 2, 1931 – November 1, 2020) was an American historian and a professor of Eastern European history at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, specializing in Romania and its history.

He was born in Schenect ...

, ''Rumania: 1866–1947'', Oxford University Press, 1994

External links

{{Nobility by nation BoyarsBoyars

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars wer ...

Boyars

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars wer ...