Bow (music) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

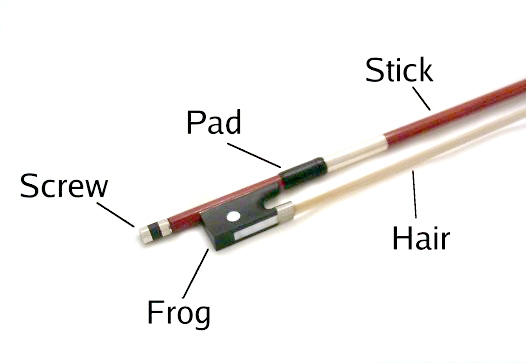

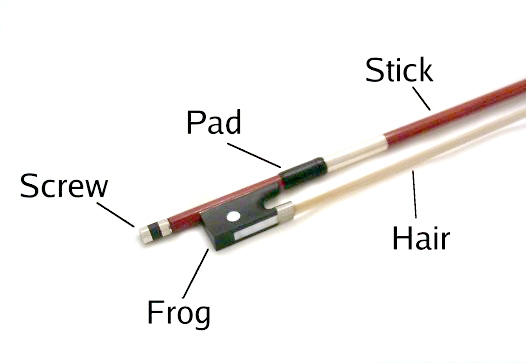

A bow consists of a specially shaped stick with other material forming a ribbon stretched between its ends, which is used to stroke the string and create sound. Different musical cultures have adopted various designs for the bow. For instance, in some bows a single cord is stretched between the ends of the stick. In the Western tradition of bow making—bows for the instruments of the

A bow consists of a specially shaped stick with other material forming a ribbon stretched between its ends, which is used to stroke the string and create sound. Different musical cultures have adopted various designs for the bow. For instance, in some bows a single cord is stretched between the ends of the stick. In the Western tradition of bow making—bows for the instruments of the

Slightly different bows, varying in weight and length, are used for the violin, viola, cello, and double bass.

These are generally variations on the same basic design. However, bassists use two distinct forms of the double bass bow. The "French" overhand bow is constructed like the bow used with other bowed orchestral instruments, and the bassist holds the stick from opposite the frog. The "German" underhand bow is broader and longer than the French bow, with a larger frog curved to fit the palm of the hand. The bassist holds the German stick with the hand loosely encompassing the frog. The German bow is the older of the two designs, having superseded the earlier arched bow. The French bow became popular with its adoption in the 19th century by virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. Both are found in the orchestra, though typically an individual bass player prefers to perform using one or the other type of bow.

Slightly different bows, varying in weight and length, are used for the violin, viola, cello, and double bass.

These are generally variations on the same basic design. However, bassists use two distinct forms of the double bass bow. The "French" overhand bow is constructed like the bow used with other bowed orchestral instruments, and the bassist holds the stick from opposite the frog. The "German" underhand bow is broader and longer than the French bow, with a larger frog curved to fit the palm of the hand. The bassist holds the German stick with the hand loosely encompassing the frog. The German bow is the older of the two designs, having superseded the earlier arched bow. The French bow became popular with its adoption in the 19th century by virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. Both are found in the orchestra, though typically an individual bass player prefers to perform using one or the other type of bow.

The kind of bow in use today was brought into its modern form largely by the bow maker François Tourte in 19th-century France. Pernambuco wood, which was imported into France to make textile dye, was found by the early French bow masters to have just the right combination of strength, resiliency, weight, and beauty. According to James McKean, Tourte's bows, "like the instruments of

The kind of bow in use today was brought into its modern form largely by the bow maker François Tourte in 19th-century France. Pernambuco wood, which was imported into France to make textile dye, was found by the early French bow masters to have just the right combination of strength, resiliency, weight, and beauty. According to James McKean, Tourte's bows, "like the instruments of

In the early bow (the Baroque bow), the natural bow stroke is a non-legato norm, producing what Leopold Mozart called a "small softness" at the beginning and end of each stroke.

A lighter, clearer sound is produced, and quick notes are cleanly articulated without the hair leaving the string.

A truly great example of such a bow, described by David Boyden, is part of the Ansley Salz Collection at the University of California at Berkeley. It was made around 1700, and is attributed to Stradivari.

Towards the middle of the century (18th century), there was a move into the Transitional period, the separation of hair from stick became greater, particularly at the head. This greater separation is necessary because the stick becomes longer and straighter, approaching a concave shape.

Up until the advent of the bow by Tourte, there was absolutely no standardization of bow features during this Transitional period, and every bow was different in weight, length and balance.

In particular, the heads varied enormously by any given maker.

Another transitional type of bow may be called the Cramer bow, after the violinist Wilhelm Cramer (1746–99) who lived the early part of his life in Mannheim (Germany) and, after 1772, in London. This bow and models comparable to it in Paris, generally prevailed between the gradual demise of the Corelli-Tartini model and the birth of the Tourte—that is, roughly 1750 until 1785.

In the view of top experts, the Cramer bow represents a decisive step towards the modern bow.

The Cramer bow and others like it were gradually rendered obsolete by the advent of François Tourte's standardized bow. The hair (on the Cramer bow) is wider than the Corelli model but still narrower than a Tourte, the screw mechanism becomes standard, and more sticks are made from pernambuco, rather than the earlier snakewood, ironwood, and china wood, which were often fluted for a portion of the length of the stick.

Fine makers of these Transitional models were Duchaîne, La Fleur, Meauchand, Tourte ''père'', and Edward Dodd.

The underlying reasons for the change from the old Corelli-Tartini model to the Cramer and, finally, to the Tourte were naturally related to musical demands on the part of composers and violinists.

Undoubtedly the emphasis on

In the early bow (the Baroque bow), the natural bow stroke is a non-legato norm, producing what Leopold Mozart called a "small softness" at the beginning and end of each stroke.

A lighter, clearer sound is produced, and quick notes are cleanly articulated without the hair leaving the string.

A truly great example of such a bow, described by David Boyden, is part of the Ansley Salz Collection at the University of California at Berkeley. It was made around 1700, and is attributed to Stradivari.

Towards the middle of the century (18th century), there was a move into the Transitional period, the separation of hair from stick became greater, particularly at the head. This greater separation is necessary because the stick becomes longer and straighter, approaching a concave shape.

Up until the advent of the bow by Tourte, there was absolutely no standardization of bow features during this Transitional period, and every bow was different in weight, length and balance.

In particular, the heads varied enormously by any given maker.

Another transitional type of bow may be called the Cramer bow, after the violinist Wilhelm Cramer (1746–99) who lived the early part of his life in Mannheim (Germany) and, after 1772, in London. This bow and models comparable to it in Paris, generally prevailed between the gradual demise of the Corelli-Tartini model and the birth of the Tourte—that is, roughly 1750 until 1785.

In the view of top experts, the Cramer bow represents a decisive step towards the modern bow.

The Cramer bow and others like it were gradually rendered obsolete by the advent of François Tourte's standardized bow. The hair (on the Cramer bow) is wider than the Corelli model but still narrower than a Tourte, the screw mechanism becomes standard, and more sticks are made from pernambuco, rather than the earlier snakewood, ironwood, and china wood, which were often fluted for a portion of the length of the stick.

Fine makers of these Transitional models were Duchaîne, La Fleur, Meauchand, Tourte ''père'', and Edward Dodd.

The underlying reasons for the change from the old Corelli-Tartini model to the Cramer and, finally, to the Tourte were naturally related to musical demands on the part of composers and violinists.

Undoubtedly the emphasis on

''The Bow, Its History, Manufacture and Use''

* Templeton, David

''Strings'' no. 105 (October 2002). * Young, Diana

''A Methodology for Investigation of Bowed String Performance Through Measurement of Violin Bowing Technique''

PhD Thesis. M.I.T., 2007.

eNotes

article on the history and making of bows.

The violin bow: a brief depiction of its history

Bows used in traditional music (''Polish folk musical instruments'')

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bow (Music) Musical instrument parts and accessories Arab inventions Mongolian inventions Turkish inventions

In

In music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, a bow is a tensioned stick which has hair (usually horse-tail hair) coated in rosin

Rosin (), also called colophony or Greek pitch ( la, links=no, pix graeca), is a solid form of resin obtained from pines and some other plants, mostly conifers, produced by heating fresh liquid resin to vaporize the volatile liquid terpene comp ...

(to facilitate friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

) affixed to it. It is moved across some part (generally some type of strings) of a musical instrument to cause vibration, which the instrument emits as sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' b ...

. The vast majority of bows are used with string instruments, such as the violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

, viola, cello, and bass, although some bows are used with musical saws and other bowed idiophones.

Materials and manufacture

A bow consists of a specially shaped stick with other material forming a ribbon stretched between its ends, which is used to stroke the string and create sound. Different musical cultures have adopted various designs for the bow. For instance, in some bows a single cord is stretched between the ends of the stick. In the Western tradition of bow making—bows for the instruments of the

A bow consists of a specially shaped stick with other material forming a ribbon stretched between its ends, which is used to stroke the string and create sound. Different musical cultures have adopted various designs for the bow. For instance, in some bows a single cord is stretched between the ends of the stick. In the Western tradition of bow making—bows for the instruments of the violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

and viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

families—a hank

Hank is a male given name. It may have been inspired by the Dutch name Henk,The Origins of 10 Nicknam ...

of horsehair

Horsehair is the long hair growing on the manes and tails of horses. It is used for various purposes, including upholstery, brushes, the bows of musical instruments, a hard-wearing fabric called haircloth, and for horsehair plaster, a wallc ...

is normally employed.

The manufacture of bows is considered a demanding craft, and well-made bows command high prices. Part of the bow maker's skill is the ability to choose high quality material for the stick. Historically, Western bows have been made of pernambuco

Pernambuco () is a States of Brazil, state of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast region of the country. With an estimated population of 9.6 million people as of 2020, making it List of Brazilian states by population, sev ...

wood from Brazil. However, pernambuco is now an endangered species whose export is regulated by international treaty, so makers are currently adopting other materials: woods such as Ipê (Tabebuia

''Tabebuia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the family Bignoniaceae.Eberhard Fischer, Inge Theisen, and Lúcia G. Lohmann. 2004. "Bignoniaceae". pages 9-38. In: Klaus Kubitzki (editor) and Joachim W. Kadereit (volume editor). ''The Families ...

) and synthetic materials, such as carbon fiber epoxy composite and fiberglass

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass ( Commonwealth English) is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass clo ...

.

For the frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek). The oldest fossil "proto-frog" ''Triadobatrachus'' is ...

, which holds and adjusts the near end of the horsehair, ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when ...

is most often used, but other materials, often decorative, were used as well, such as ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

and tortoiseshell. Materials such as mother of pearl or abalone shell are often used on the slide that covers the mortise, as well as in round decorative "eyes" inlaid on the side surfaces. Sometimes "Parisian eyes" are used, with the circle of shell surrounded by a metal ring. The metal parts of the frog, or mountings, may be used by the maker to mark various grades of bow, ordinary bows being mounted with nickel silver

Nickel silver, Maillechort, German silver, Argentan, new silver, nickel brass, albata, alpacca, is a copper alloy with nickel and often zinc. The usual formulation is 60% copper, 20% nickel and 20% zinc. Nickel silver does not contain the eleme ...

, better bows with silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, and the finest being gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

-mounted. (Not all makers adhere uniformly to this practice.) Near the frog is the ''grip'', which is made of a wire, silk, or " whalebone" wrap and a thumb cushion made of leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hog ...

or snakeskin

Snakeskin may either refer to the skin of a live snake, the shed skin of a snake after molting, or to a type of leather that is made from the hide of a dead snake. Snakeskin and scales can have varying patterns and color formations, providing prot ...

. The tip plate of the bow may be made of bone, ivory, mammoth ivory, or metal, such as silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

.

A bow maker or ' typically uses between 150 and 200 hairs from the tail of a horse for a violin bow. Bows for other members of the violin family typically have a wider ribbon, using more hairs. There is a widely held belief among string players, neither proven nor disproven scientifically, that white hair produces a "smoother" sound and black hair (used mainly for double bass bows) is coarser and thus produces a "rougher" sound. Lower quality (inexpensive) bows often use nylon or synthetic hair, and some use bleached horse hair to give the appearance of higher quality. Rosin

Rosin (), also called colophony or Greek pitch ( la, links=no, pix graeca), is a solid form of resin obtained from pines and some other plants, mostly conifers, produced by heating fresh liquid resin to vaporize the volatile liquid terpene comp ...

, or colophony

Rosin (), also called colophony or Greek pitch ( la, links=no, pix graeca), is a solid form of resin obtained from pines and some other plants, mostly conifers, produced by heating fresh liquid resin to vaporize the volatile liquid terpene comp ...

, a hard, sticky substance made from resin

In polymer chemistry and materials science, resin is a solid or highly viscous substance of plant or synthetic origin that is typically convertible into polymers. Resins are usually mixtures of organic compounds. This article focuses on n ...

(sometimes mixed with wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

), is regularly applied to the bow hair to increase friction.

In making a wooden bow, the greater part of the woodworking is done on a straight stick. According to James McKean,McKean, James N. (1996) ''Commonsense Instrument Care''. San Anselmo, California: String Letter Publishing. "the bow maker graduates the stick in precise gradations so that it is evenly flexible throughout". These gradations were originally calculated by François Tourte, discussed below. To shape the curve or "camber" of the bow stick, the maker carefully heats the stick in an alcohol flame, a few inches at a time, bending the heated stick gradually—using a metal or wooden template to get the model's exact curve and shape.

The art of making wooden bows has changed little since the 19th century. Most modern composite sticks roughly resemble the Tourte design. Various inventors have explored new ways of bow-making. The Incredibow, for example, has a straight stick cambered only by the fixed tension of the synthetic hair.

Types

Slightly different bows, varying in weight and length, are used for the violin, viola, cello, and double bass.

These are generally variations on the same basic design. However, bassists use two distinct forms of the double bass bow. The "French" overhand bow is constructed like the bow used with other bowed orchestral instruments, and the bassist holds the stick from opposite the frog. The "German" underhand bow is broader and longer than the French bow, with a larger frog curved to fit the palm of the hand. The bassist holds the German stick with the hand loosely encompassing the frog. The German bow is the older of the two designs, having superseded the earlier arched bow. The French bow became popular with its adoption in the 19th century by virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. Both are found in the orchestra, though typically an individual bass player prefers to perform using one or the other type of bow.

Slightly different bows, varying in weight and length, are used for the violin, viola, cello, and double bass.

These are generally variations on the same basic design. However, bassists use two distinct forms of the double bass bow. The "French" overhand bow is constructed like the bow used with other bowed orchestral instruments, and the bassist holds the stick from opposite the frog. The "German" underhand bow is broader and longer than the French bow, with a larger frog curved to fit the palm of the hand. The bassist holds the German stick with the hand loosely encompassing the frog. The German bow is the older of the two designs, having superseded the earlier arched bow. The French bow became popular with its adoption in the 19th century by virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. Both are found in the orchestra, though typically an individual bass player prefers to perform using one or the other type of bow.

Bowing

The characteristic long, sustained, and singing sound produced by the violin, viola, violoncello, and double bass is due to the drawing of the bow against their strings. This sustaining of musical sound with a bow is comparable to a singer using breath to sustain sounds and sing long, smooth, or ''legato'' melodies. In modern practice, the bow is almost always held in the right hand while the left is used for fingering. When the player pulls the bow across the strings (such that the frog moves away from the instrument), it is called a ''down-bow''; pushing the bow so the frog moves toward the instrument is an ''up-bow'' (the directions "down" and "up" are literally descriptive for violins and violas and are employed in analogous fashion for the cello and double bass). Two consecutive notes played in the same bow direction are referred to as a hooked bow; a down-bow following a whole down-bow is called a retake. Generally, the player uses down-bow for strong musical beats and up-bow for weak beats. However, this is reversed in theviola da gamba

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitch ...

—players of violin family instruments look like they are "pulling" on the strong beats, where gamba players look like they are "stabbing" on the strong beats. The difference may result from the different ways player hold the bow in these instrument families: violin/viola/cello players hold the wood part of the bow closer to the palm, whereas gamba players use the opposite orientation, with the horsehair closer. The orientation appropriate to each instrument family permits the stronger wrist muscles (flexors) to reinforce the strong beat.

String players control their tone quality by touching the bow to the strings at varying distances from the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

, emphasizing the higher harmonics by playing sul ponticello

A variety of musical terms are likely to be encountered in Sheet music, printed scores, music reviews, and program notes. Most of the terms Italian musical terms used in English, are Italian, in accordance with the Italian origins of many Europea ...

("on the bridge"), or reducing them, and so emphasizing the fundamental frequency, by playing sul tasto

A variety of musical terms are likely to be encountered in printed scores, music reviews, and program notes. Most of the terms are Italian, in accordance with the Italian origins of many European musical conventions. Sometimes, the special mus ...

("on the fingerboard").

Occasionally, composers ask the player to use the bow by touching the strings with the wood rather than the hair; this is known by the Italian phrase ''col legno

In music for bowed string instrument

Bowed string instruments are a subcategory of string instruments that are played by a bow rubbing the strings. The bow rubbing the string causes vibration which the instrument emits as sound.

Despite th ...

'' ("with the wood"). ''Coll'arco'' ("with the bow") is the indication to use the bow hair to create the sound in the normal way.

History

Origin

The question of when and where the bow was invented is of interest because the technique of using it to produce sound on a stringed instrument has led to many important historical and regional developments in music, as well as the variety of instruments used. Pictorial and sculptural evidence from early Egyptian, Indian, Hellenic, and Anatolian civilizations indicate that plucked stringed instruments existed long before the technique of bowing developed. In spite of the ancient origins of the bow and arrow, it would appear that bowed string instruments only developed during a comparatively recent period. Eric Halfpenny, writing in the 1988 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', says, "bowing can be traced as far back as the Islamic civilization of the 10th century ... it seems likely that the principle of bowing originated among the nomadic horse riding cultures of Central Asia, whence it spread quickly through Islam and the East, so that by 1000 it had almost simultaneously reached China, Java, North Africa, the Near East and Balkans, and Europe." Halfpenny notes that in many Eurasian languages the word for "bridge" etymologically means "horse," and that the Chinese regarded their own bowed instruments ''(huqin

''Huqin'' () is a family of bowed string instruments, more specifically, a spike fiddle popularly used in Chinese music. The instruments consist of a round, hexagonal, or octagonal sound box at the bottom with a neck attached that protrudes u ...

)'' as having originated with the "barbarians" of Central Asia.

The Central Asian theory is endorsed by Werner Bachmann, writing in '' The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians''. Bachmann notes evidence from a 10th-century Central Asian wall painting for bowed instruments in what is now the city of Kurbanshaid in Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

.

Circumstantial evidence also supports the Central Asian theory. All the elements that were necessary for the invention of the bow were probably present among the Central Asian horse riding peoples at the same time:

*In a society of horse-mounted warriors (the horse peoples included the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

and the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

), horsehair obviously would have been available.

*Central Asian horse warriors specialized in the military bow, which could easily have served the inventor as a temporary way to hold horsehair at high tension.

*To this day, horsehair for bows is taken from places with harsh cold climates, including Mongolia, as such hair offers a better grip on the strings.

*Rosin

Rosin (), also called colophony or Greek pitch ( la, links=no, pix graeca), is a solid form of resin obtained from pines and some other plants, mostly conifers, produced by heating fresh liquid resin to vaporize the volatile liquid terpene comp ...

, crucial for creating sound even with coarse horsehair, is used by traditional archers

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In mo ...

to maintain the integrity of the string and (mixed with beeswax) to protect the finish of the bow.

(From this information it can be seen that the invention of the bow originates from a Mongol warrior, having just used rosin on his equipment, idly stroking his harp or lyre with a rosin-dusted finger, producing a brief continuous sound, thus inspiring them to restring their bow with horsehair, leading to the earliest example of the bow)

However the bow was invented, it spread quickly and widely. The Central Asian horse peoples occupied a territory that included the Silk Road, along which merchants and travelers transported goods and innovations rapidly for thousands of miles (including, via India, by sea to Java). This would account for the near-simultaneous appearance of the musical bow in the many locations cited by Halfpenny.

Arabic ''rabāb''

The Arabicrabāb

The ''rebab'' ( ar, ربابة, ''rabāba'', variously spelled ''rebap'', ''rubob'', ''rebeb'', ''rababa'', ''rabeba'', ''robab'', ''rubab'', ''rebob'', etc) is the name of several related string instruments that independently spread via I ...

is a type of a bowed string instrument so named no later than the 8th century and spread via Islamic trading routes over much of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, parts of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, and the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. It is the earliest known bowed instrument, and the ancestor of all European bowed instruments, including the rebec

The rebec (sometimes rebecha, rebeckha, and other spellings, pronounced or ) is a bowed stringed instrument of the Medieval era and the early Renaissance. In its most common form, it has a narrow boat-shaped body and one to five strings.

Origi ...

, lyra and violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

.

Modern Western bow

The kind of bow in use today was brought into its modern form largely by the bow maker François Tourte in 19th-century France. Pernambuco wood, which was imported into France to make textile dye, was found by the early French bow masters to have just the right combination of strength, resiliency, weight, and beauty. According to James McKean, Tourte's bows, "like the instruments of

The kind of bow in use today was brought into its modern form largely by the bow maker François Tourte in 19th-century France. Pernambuco wood, which was imported into France to make textile dye, was found by the early French bow masters to have just the right combination of strength, resiliency, weight, and beauty. According to James McKean, Tourte's bows, "like the instruments of Stradivari

Antonio Stradivari (, also , ; – 18 December 1737) was an Italian luthier and a craftsman of string instruments such as violins, cellos, guitars, violas and harps. The Latinized form of his surname, '' Stradivarius'', as well as the collo ...

, are still considered to be without equal."

Historical bows

The early 18th-century bow referred to as the Corelli-Tartini model is also referred to as the Italian 'sonata' bow. This basic Baroque bow supplanted by 1725 an earlier French dance bow that was short with a little point. The French dance bow was held with the thumb under the hair and played with short, quick strokes for rhythmic dance music. The Italian sonata bow was longer, from 24 to 28 inches (61–71 cm.), with a straight or slightly convex stick. The head is described as a pike's head, and the frog is either fixed (the clip-in bow) or has a screw mechanism. The screw is an early improvement, indicative of further changes to come. As compared to a modern Tourte-style bow, the Corelli-Tartini model is shorter and lighter, especially at the tip, the balance point is lower down on the stick, the hair more yielding, and the ribbon of hair narrower—about 6 mm wide. In the early bow (the Baroque bow), the natural bow stroke is a non-legato norm, producing what Leopold Mozart called a "small softness" at the beginning and end of each stroke.

A lighter, clearer sound is produced, and quick notes are cleanly articulated without the hair leaving the string.

A truly great example of such a bow, described by David Boyden, is part of the Ansley Salz Collection at the University of California at Berkeley. It was made around 1700, and is attributed to Stradivari.

Towards the middle of the century (18th century), there was a move into the Transitional period, the separation of hair from stick became greater, particularly at the head. This greater separation is necessary because the stick becomes longer and straighter, approaching a concave shape.

Up until the advent of the bow by Tourte, there was absolutely no standardization of bow features during this Transitional period, and every bow was different in weight, length and balance.

In particular, the heads varied enormously by any given maker.

Another transitional type of bow may be called the Cramer bow, after the violinist Wilhelm Cramer (1746–99) who lived the early part of his life in Mannheim (Germany) and, after 1772, in London. This bow and models comparable to it in Paris, generally prevailed between the gradual demise of the Corelli-Tartini model and the birth of the Tourte—that is, roughly 1750 until 1785.

In the view of top experts, the Cramer bow represents a decisive step towards the modern bow.

The Cramer bow and others like it were gradually rendered obsolete by the advent of François Tourte's standardized bow. The hair (on the Cramer bow) is wider than the Corelli model but still narrower than a Tourte, the screw mechanism becomes standard, and more sticks are made from pernambuco, rather than the earlier snakewood, ironwood, and china wood, which were often fluted for a portion of the length of the stick.

Fine makers of these Transitional models were Duchaîne, La Fleur, Meauchand, Tourte ''père'', and Edward Dodd.

The underlying reasons for the change from the old Corelli-Tartini model to the Cramer and, finally, to the Tourte were naturally related to musical demands on the part of composers and violinists.

Undoubtedly the emphasis on

In the early bow (the Baroque bow), the natural bow stroke is a non-legato norm, producing what Leopold Mozart called a "small softness" at the beginning and end of each stroke.

A lighter, clearer sound is produced, and quick notes are cleanly articulated without the hair leaving the string.

A truly great example of such a bow, described by David Boyden, is part of the Ansley Salz Collection at the University of California at Berkeley. It was made around 1700, and is attributed to Stradivari.

Towards the middle of the century (18th century), there was a move into the Transitional period, the separation of hair from stick became greater, particularly at the head. This greater separation is necessary because the stick becomes longer and straighter, approaching a concave shape.

Up until the advent of the bow by Tourte, there was absolutely no standardization of bow features during this Transitional period, and every bow was different in weight, length and balance.

In particular, the heads varied enormously by any given maker.

Another transitional type of bow may be called the Cramer bow, after the violinist Wilhelm Cramer (1746–99) who lived the early part of his life in Mannheim (Germany) and, after 1772, in London. This bow and models comparable to it in Paris, generally prevailed between the gradual demise of the Corelli-Tartini model and the birth of the Tourte—that is, roughly 1750 until 1785.

In the view of top experts, the Cramer bow represents a decisive step towards the modern bow.

The Cramer bow and others like it were gradually rendered obsolete by the advent of François Tourte's standardized bow. The hair (on the Cramer bow) is wider than the Corelli model but still narrower than a Tourte, the screw mechanism becomes standard, and more sticks are made from pernambuco, rather than the earlier snakewood, ironwood, and china wood, which were often fluted for a portion of the length of the stick.

Fine makers of these Transitional models were Duchaîne, La Fleur, Meauchand, Tourte ''père'', and Edward Dodd.

The underlying reasons for the change from the old Corelli-Tartini model to the Cramer and, finally, to the Tourte were naturally related to musical demands on the part of composers and violinists.

Undoubtedly the emphasis on cantabile

In music, ''cantabile'' , an Italian word, means literally "singable" or "songlike". In instrumental music, it is a particular style of playing designed to imitate the human voice.

For 18th-century composers, ''cantabile'' is often synonymous wit ...

, especially the long drawn out and evenly sustained phrase, required a generally longer bow and also a somewhat wider ribbon of hair. These new bows were ideal to fill the new, very large concert halls with sound and worked great with the late classical and the new romantic repertoire.

Today, with the rise of the historically informed performance movement, string players have developed a revived interest in the lighter, pre-Tourte bow, as more suitable for playing stringed instruments made in pre-19th-century style.

Stradivarius bows

A Stradivari bow, The King Charles IV Violin Bow attributed to the Stradivari Workshop, is currently in the collection of theNational Music Museum

The National Music Museum: America's Shrine to Music & Center for Study of the History of Musical Instruments (NMM) is a musical instrument museum in Vermillion, South Dakota, United States. It was founded in 1973 on the campus of the Universit ...

Object number: 04882, at the University of South Dakota

The University of South Dakota (USD) is a public research university in Vermillion, South Dakota. Established by the Dakota Territory legislature in 1862, 27 years before the establishment of the state of South Dakota, USD is the flagship uni ...

in Vermillion, South Dakota

Vermillion ( lkt, Waséoyuze; "The Place Where Vermilion is Obtained") is a city in and the county seat of Clay County. It is in the southeastern corner of South Dakota, United States, and is the state's 12th-largest city. According to the 2020 ...

. The Rawlins Gallery violin bow, NMM 4882, is attributed to the workshop of Antonio Stradivari

Antonio Stradivari (, also , ; – 18 December 1737) was an Italian luthier and a craftsman of string instruments such as violins, cellos, guitars, violas and harps. The Latinized form of his surname, '' Stradivarius'', as well as the collo ...

, Cremona, 1700.

This bow is one of two bows (the other in a private collection in London) attributed to the workshop of Antonio Stradivari.

Other types of bow

The Chinese yazheng and ''yaqin'', and Korean ajaeng zithers are generally played by "bowing" with a rosined stick, which creates friction against the strings without any horsehair. Thehurdy-gurdy

The hurdy-gurdy is a string instrument that produces sound by a hand-crank-turned, rosined wheel rubbing against the strings. The wheel functions much like a violin bow, and single notes played on the instrument sound similar to those of a vi ...

's strings are similarly set into vibration by means of a "rosin wheel," a wooden wheel that contacts the strings as it is rotated by means of a crank handle, creating a "bowed" tone.

Maintenance

Careful owners always loosen the hair on a bow before putting it away. James McKean recommends that the owner "loosen the hair completely, then bring it back just a single turn of the button." The goal is to "keep the hair even but allow the bow to relax." Over-tightening the bow, however, can also be damaging to the stick and cause it to break. Since hairs may break in service, bows must be periodically rehaired, an operation usually performed by professional bow makers rather than by the instrument owner. Bows sometimes lose their correct camber (see above), and are recambered using the same heating method as is used in the original manufacture. Lastly, the grip or winding of the bow must occasionally be replaced to maintain a good grip and protect the wood. These repairs are usually left to professionals, as the head of the bow is extremely fragile, and a poor rehair, or a broken ivory plate on the tip, can lead to ruining the bow.Nomenclature

In vernacular speech, the bow is occasionally called a ''fiddlestick''. Bows for particular instruments are often designated as such: ''violin bow'', ''cello bow'', and so on.See also

* Bariolage * Bowed guitar * Curved bowReferences

Sources * Harnoncourt, Nikolaus. ''Baroque music today: music as speech.'' Amadeus Press, c. 1988. *Saint-George, Henry (1866–1917). ''The Bow'' (London, 1896; 2: 1909). *Seletsky, Robert E., "New Light on the Old Bow," Part 1: ''Early Music'' 5/2004, pp. 286–96; Part 2: ''Early Music'' 8/2004, pp. 415–26. * * * NotesFurther reading

* Bachmann, Werner. ''The Origins of Bowing and the Development of Bowed Instruments Up to the Thirteenth Century''. London, Oxford U.P., 1969. * Saint-George, Henry''The Bow, Its History, Manufacture and Use''

* Templeton, David

''Strings'' no. 105 (October 2002). * Young, Diana

''A Methodology for Investigation of Bowed String Performance Through Measurement of Violin Bowing Technique''

PhD Thesis. M.I.T., 2007.

External links

eNotes

article on the history and making of bows.

The violin bow: a brief depiction of its history

Bows used in traditional music (''Polish folk musical instruments'')

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bow (Music) Musical instrument parts and accessories Arab inventions Mongolian inventions Turkish inventions