Bouvet Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

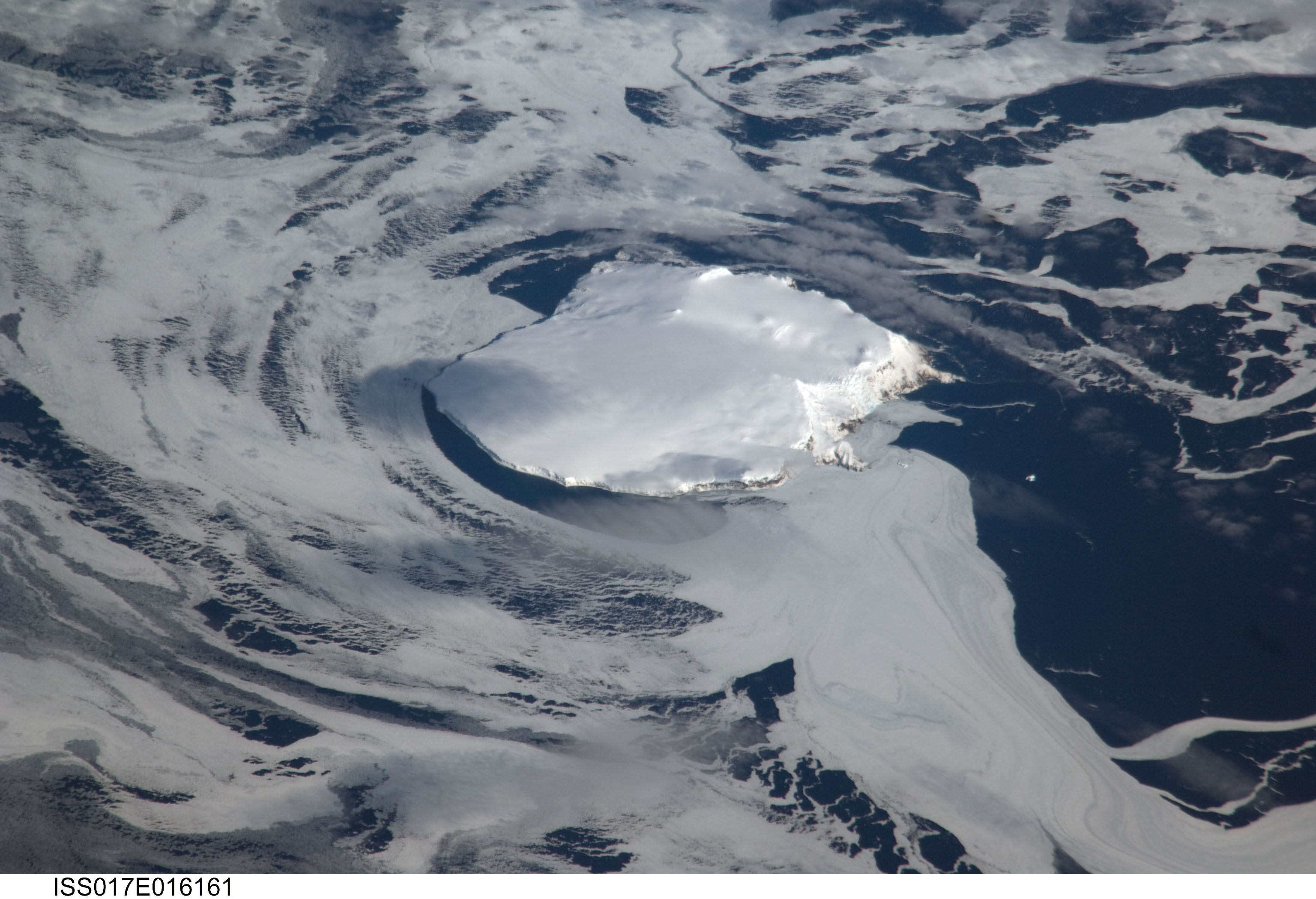

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a

The island was discovered on by

The island was discovered on by

In 1927, the First ''Norvegia'' Expedition, led by Harald Horntvedt and financed by

In 1927, the First ''Norvegia'' Expedition, led by Harald Horntvedt and financed by

Bouvetøya is a volcanic island constituting the top of a shield volcano just off the

Bouvetøya is a volcanic island constituting the top of a shield volcano just off the

The harsh climate and ice-bound terrain limits non-animal life to

The harsh climate and ice-bound terrain limits non-animal life to  The island has been designated as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of its importance as a breeding ground for

The island has been designated as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of its importance as a breeding ground for

Bouvetøya is one of three dependencies of Norway. Unlike Peter I Island and

Bouvetøya is one of three dependencies of Norway. Unlike Peter I Island and

The Most Remote Island in the World

��''Sometimes Interesting'', 11 November 2012

Amateur Radio DX Pedition to Bouvet Island 3Y0Z

Bouvet Island, the most remote island in the World

��Random-Times.com, June 2018' {{Authority control Antarctic region 1920s establishments in Antarctica Dependencies of Norway Important Bird Areas of Antarctica Important Bird Areas of Norwegian overseas territories Important Bird Areas of subantarctic islands Inactive volcanoes Islands of the South Atlantic Ocean Mid-Atlantic Ridge Nature reserves in Norway Penguin colonies Polygenetic shield volcanoes Ridge volcanoes Seabird colonies Seal hunting States and territories established in 1928 Uninhabited islands of Norway Volcanoes of Norway Volcanoes of the Southern Ocean

subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands ...

volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North ...

, making it the world's most remote island. It is not part of the southern region covered by the Antarctic Treaty System.

The island lies north of the Princess Astrid Coast of Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addi ...

, Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, east of the South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

, south of Gough Island, and south-southwest of the coast of South Africa. It has an area of , 93 percent of which is covered by a glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

. The centre of the island is the ice-filled crater of an inactive volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the Crust (geology), crust of a Planet#Planetary-mass objects, planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and volcanic gas, gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Ear ...

. Some skerries and one smaller island, Larsøya

Larsøya, sometimes anglicized as Lars Island, is a rocky island, less than long, which lies just off the southwestern extremity of the island of Bouvetøya in the South Atlantic Ocean. It was first roughly charted in 1898 by a German expeditio ...

, lie along its coast. Nyrøysa, created by a rock slide in the late 1950s, is the only easy place to land and is the location of a weather station

A weather station is a facility, either on land or sea, with instruments and equipment for measuring atmospheric conditions to provide information for weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate. The measurements taken include tempera ...

.

The island was first spotted on 1 January 1739 by the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier

Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier (14 January 1705 – 1786) was a French sailor, explorer, and governor of the Mascarene Islands.

He was orphaned at the age of seven and after being educated in Paris, he was sent to Saint Malo to study n ...

, during a French exploration mission in the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

with the ships ''Aigle'' and ''Marie''. They did not make landfall. He mislabeled the coordinates for the island, and it was not sighted again until 1808, when the British whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

James Lindsay encountered it and named it Lindsay Island. The first claim to have landed on the island was made by the American sailor Benjamin Morrell

Benjamin Morrell (July 5, 1795 – 1838 or 1839?) was an American sea captain, explorer and trader who made a number of voyages, mainly to the Atlantic, the Southern Ocean and the Pacific Islands. In a ghost-written memoir, ''A Narrative of Four ...

, although this claim is disputed. In 1825, the island was claimed for the British Crown by George Norris, who named it Liverpool Island. He also reported having sighted another island nearby, which he named Thompson Island, but this was later shown to be a phantom island.

In 1927, the first ''Norvegia'' expedition landed on the island, and claimed it for Norway. At that point, the island was given its current name of ''Bouvet Island'' ("Bouvetøya" in Norwegian). In 1930, following resolution of a dispute with the United Kingdom over claiming rights, it was declared a Norwegian dependency. In 1971, it was designated a nature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

.

History

Discovery and early sightings

The island was discovered on by

The island was discovered on by Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier

Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier (14 January 1705 – 1786) was a French sailor, explorer, and governor of the Mascarene Islands.

He was orphaned at the age of seven and after being educated in Paris, he was sent to Saint Malo to study n ...

, commander of the French ships ''Aigle'' and ''Marie''. Bouvet, who was searching for a presumed large southern continent, spotted the island through the fog and named the cape he saw Cap de la Circoncision. He was not able to land and did not circumnavigate

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magel ...

his discovery, thus not clarifying if it was an island or part of a continent.

His plotting of its position was inaccurate, leading several expeditions to fail to find the island. James Cook's second voyage set off from Cape Verde on 22 November 1772 and attempted to find the island, but also failed.

The next expedition to spot the island was in 1808 by James Lindsay, captain of the Samuel Enderby & Sons' (SE&S) snow

Snow comprises individual ice crystals that grow while suspended in the atmosphere—usually within clouds—and then fall, accumulating on the ground where they undergo further changes.

It consists of frozen crystalline water throughout ...

whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

''Swan''. ''Swan'' and another Enderby whaler, were in company when they reached the island and recorded its position, though they were unable to land. Lindsay could confirm that the "cape" was indeed an island. The next expedition to arrive at the island was American Benjamin Morrell

Benjamin Morrell (July 5, 1795 – 1838 or 1839?) was an American sea captain, explorer and trader who made a number of voyages, mainly to the Atlantic, the Southern Ocean and the Pacific Islands. In a ghost-written memoir, ''A Narrative of Four ...

and his seal hunting ship ''Wasp''. Morrell, by his own account, found the island without difficulty (with "improbable ease", in the words of historian William Mills) before landing and hunting 196 seals. In his subsequent lengthy description, Morrell does not mention the island's most obvious physical feature: Its permanent ice cover.

This has caused some commentators to doubt whether he actually visited the island.

On 10 December 1825, SE&S's George Norris, master of the ''Sprightly'', landed on the island, named it Liverpool Island and claimed it for the British Crown and George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

on 16 December. The next expedition to spot the island was Joseph Fuller and his ship ''Francis Allyn'' in 1893, but he was not able to land on the island. German Carl Chun's Valdivia Expedition

The ''Valdivia'' Expedition, or ''Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition'' (German Deep Sea Expedition), was a scientific expedition organised and funded by the German Empire under Kaiser Wilhelm II and was named after the ship which was bought and outfitt ...

arrived at the island in 1898. They were not able to land, but dredged the seabed for geological samples. They were also the first to accurately fix the island's position. At least three sealing vessels visited the island between 1822–1895. A voyage of exploration in 1927–1928 also took seal pelts.

Norris also spotted a second island in 1825, which he named Thompson Island, which he placed north-northeast of Liverpool Island. Thompson Island was also reported in 1893 by Fuller, but in 1898 Chun did not report seeing such an island, nor has anyone since. However, Thompson Island continued to appear on maps as late as 1943. A 1967 paper suggested that the island might have disappeared in an undetected volcanic eruption, but in 1997 it was discovered that the ocean is more than deep in the area.

Norwegian annexation

In 1927, the First ''Norvegia'' Expedition, led by Harald Horntvedt and financed by

In 1927, the First ''Norvegia'' Expedition, led by Harald Horntvedt and financed by Lars Christensen

Lars Christensen (6 April 1884 – 10 December 1965) was a Norwegian shipowner and whaling magnate. He was also a philanthropist with a keen interest in the exploration of Antarctica.

Career

Lars Christensen was born at Sandar in Vestfold, No ...

, was the first to make an extended stay on the island. Observations and surveying were conducted on the islands and oceanographic

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamic ...

measurements performed in the sea around it. At Ny Sandefjord, a small hut was erected and, on 1 December, the Norwegian flag

The national flag of Norway ( nb, Norges flagg; nn, Noregs flagg; ) is red with a navy blue Scandinavian cross fimbriated in white that extends to the edges of the flag; the vertical part of the cross is shifted to the hoist side in the style ...

was hoisted and the island claimed for Norway. The annexation was established by a royal decree on 23 January 1928.

The claim was initially protested by the United Kingdom, on the basis of Norris's landing and annexation. However, the British position was weakened by Norris's sighting of two islands and the uncertainty as to whether he had been on Thompson or Liverpool (i.e. Bouvet) Island. Norris's positioning deviating from the correct location combined with the island's small size and lack of a natural harbour

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

made the UK accept the Norwegian claim. This resulted in diplomatic negotiations between the two countries, and in November 1929, Britain renounced its claim to the island.

The Second ''Norvegia'' Expedition arrived in 1928 with the intent of establishing a staffed meteorological radio station, but a suitable location could not be found. By then both the flagpole and hut from the previous year had been washed away. The Third ''Norvegia'' Expedition, led by Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen

Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen (7 June 1890 – 3 June 1965) was a Norwegian aviation pioneer, military officer, polar explorer and businessman. Among his achievements, he is generally regarded a founder of the Royal Norwegian Air Force.

Background

Ri ...

, arrived the following year and built a new hut at Kapp Circoncision and on Larsøya. The expedition carried out aerial photography

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing airc ...

of the island and was the first Antarctic expedition to use aircraft. The ''Dependency Act'', passed by the Parliament of Norway on 27 February 1930, established Bouvet Island as a dependency, along with Peter I Island and Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addi ...

. The eared seal

An eared seal or otariid or otary is any member of the marine mammal family Otariidae, one of three groupings of pinnipeds. They comprise 15 extant species in seven genera (another species became extinct in the 1950s) and are commonly known eith ...

was protected on and around the island in 1929 and in 1935 all seals around the island were protected.

Recent history

In 1955, the South African frigate SAS ''Transvaal'' visited the island. Nyrøysa, a rock-strewn ice-free area, the largest such on Bouvet, was created sometime between 1955 and 1958, probably by a landslide. In 1964 the island was visited by the British naval ship HMS ''Protector''. One of ''Protectors two Westland Whirlwind helicopters landed a small survey team on the island led byLieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

Alan Crawford at Nyrøysa for a brief visit. Shortly after landing the survey team discovered an abandoned lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

in a small lagoon formed by the eruption. With very little time a brief search was made but no other signs of human activity were found and the identity of the lifeboat remained a mystery for many years. On 17 December 1971, the entire island and its territorial waters were protected as a nature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

. A scientific landing was made in 1978, during which the underground temperature was measured to be . In addition to scientific surveys, the lifeboat found by the ''Protector'' team was recovered from Nyrøysa, although no other signs of people were found. The lifeboat was believed to belong to a Soviet scientific reconnaissance vessel.

The Vela Incident

The Vela incident was an unidentified double flash of light detected by an American Vela Hotel satellite on 22 September 1979 near the South African territory of Prince Edward Islands in the Indian Ocean, roughly midway between Africa and Antar ...

took place on 22 September 1979, on or above the sea between Bouvetøya and Prince Edward Islands

The Prince Edward Islands are two small uninhabited islands in the sub-Antarctic Indian Ocean that are part of South Africa. The islands are named Marion Island (named after Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, 1724–1772) and Prince Edward Island ...

, when the American Vela Hotel satellite 6911 registered an unexplained double flash. This observation has been variously interpreted as a meteor, or instrumentation glitch, but most independent assessments conclude it was an undeclared joint nuclear test carried out by South Africa and Israel.

Since the 1970s, the island has been visited frequently by Norwegian Antarctic expeditions. In 1977, an automated weather station

A weather station is a facility, either on land or sea, with instruments and equipment for measuring atmospheric conditions to provide information for weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate. The measurements taken include tempera ...

was constructed, and for two months in 1978 and 1979 a staffed weather station was operated. In March 1985, a Norwegian expedition experienced sufficiently clear weather to allow the entire island to be photographed from the air, resulting in the first accurate map of the whole island, 247 years after its discovery. The Norwegian Polar Institute established a research station, made of shipping container

A shipping container is a container with strength suitable to withstand shipment, storage, and handling. Shipping containers range from large reusable steel boxes used for intermodal shipments to the ubiquitous corrugated boxes. In the context of ...

s, at Nyrøysa in 1996. On 23 February 2006, the island experienced a magnitude 6.2 earthquake whose epicentre was about away, weakening the station's foundation and causing it to be blown to sea during a winter storm. In 2014, a new research station was sent from Tromsø

Tromsø (, , ; se, Romsa ; fkv, Tromssa; sv, Tromsö) is a municipality in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Tromsø.

Tromsø lies in Northern Norway. The municipality is the ...

in Norway, via Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, to Bouvet. The new station is designed to house six people for periods of two to four months.

In the mid-1980s, Bouvetøya, Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger ...

, and Svalbard were considered as locations for the new Norwegian International Ship Register Norwegian International Ship Register or NIS is a separate Norwegian ship register for Norwegian vessels aimed at competing with flags of convenience registers such as Panama and Liberia. Originally proposed by Erling Dekke Næss in 1984, it was ...

, but the flag of convenience

Flag of convenience (FOC) is a business practice whereby a ship's owners register a merchant ship in a ship register of a country other than that of the ship's owners, and the ship flies the civil ensign of that country, called the flag state ...

registry was ultimately established in Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula o ...

, Norway, in 1987.

In 2007, the island was added to Norway's tentative list of nominations as a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

as part of the transnational nomination of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

Krill fishing in the Southern Ocean is subject to the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, also known as the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, and CCAMLR, is part of the Antarctic Treaty System.

The convention was opened for s ...

, which defines maximum catch quotas for a sustainable exploitation of Antarctic krill. Surveys conducted in 2000 showed high concentration of krill around Bouvetøya. In 2004, Aker BioMarine

Aker BioMarine is a Norwegian fishing and biotech company providing krill products through a fully documented and secured catch and process chain. Based in Oslo, Aker BioMarine is part of the Aker Group and the company also created Eco-Harvestin ...

was awarded a concession to fish krill, and additional quotas were awarded from 2008 for a total catch of . There is a controversy as to whether the fisheries are sustainable, particularly in relation to krill being important food for whales. In 2009, Norway filed with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to extend the outer limit of the continental shelf past surrounding the island.

The ''Hanse Explorer'' expedition ship visited Bouvet Island on 20 and 21 February 2012 as part of "Expédition pour le Futur". The expedition's goal was to land and climb the highest point on the island.

Bouvet Island is assigned the amateur radio callsign prefix 3Y0, and several amateur radio DX-pedition

A DX-pedition is an expedition to what is considered an exotic place by amateur radio operators and DX listeners, typically because of its remoteness, access restrictions, or simply because there are very few radio amateurs active from that pl ...

s have been conducted to the island. the 3Y0J DX-pedition to Bouvet Island is planned for January 2023.

Geography and geology

Bouvetøya is a volcanic island constituting the top of a shield volcano just off the

Bouvetøya is a volcanic island constituting the top of a shield volcano just off the Southwest Indian Ridge

The Southwest Indian Ridge (SWIR) is a mid-ocean ridge located along the floors of the south-west Indian Ocean and south-east Atlantic Ocean. A divergent tectonic plate boundary separating the Somali Plate to the north from the Antarctic Plate t ...

in the South Atlantic Ocean. The island measures and covers an area of , including a number of small rocks and skerries and one sizable island, Larsøya

Larsøya, sometimes anglicized as Lars Island, is a rocky island, less than long, which lies just off the southwestern extremity of the island of Bouvetøya in the South Atlantic Ocean. It was first roughly charted in 1898 by a German expeditio ...

.

It is located in the Subantarctic, south of the Antarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. Antarctic waters pr ...

, which, by some definitions, would place the island in the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

.

Bouvet Island is the most remote island in the world.

The closest land is Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addi ...

of Antarctica, which is to the south, and Gough Island, to the north. The closest inhabited location is Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying approximately from Cape Town in South Africa, from Saint Helena a ...

island, to the northwest. To its west, the South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

lie about away, and to its east are the Prince Edward Islands

The Prince Edward Islands are two small uninhabited islands in the sub-Antarctic Indian Ocean that are part of South Africa. The islands are named Marion Island (named after Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, 1724–1772) and Prince Edward Island ...

, about away.

Nyrøysa is a terrace located on the north-west coast of the island. Created by a rock slide sometime between 1955 and 1957, it is the island's easiest access point. It is the site of the automatic weather station. The north-west corner is the peninsula of Kapp Circoncision. From there, east to Kapp Valdivia, the coast is known as Morgenstiernekysten.

Store Kari is an islet located east of the cape. From Kapp Valdivia, southeast to Kapp Lollo, on the east side of the island, the coast is known as Victoria Terrasse. From there to Kapp Fie at the southeastern corner, the coast is known as Mowinckelkysten. Svartstranda is a section of black sand

Black sand is sand that is black in color. One type of black sand is a heavy, glossy, partly magnetic mixture of usually fine sands containing minerals such as magnetite, found as part of a placer deposit. Another type of black sand, found on ...

which runs along the section from Kapp Meteor Kapp or KAPP may refer to:

*Kapp (headcovering), a headcovering worn by many Anabaptist Christian women

*Kapp, Norway, a village in Østre Toten municipality in Innlandet county, Norway

*Kapp Records, a record label

*KAPP (TV), the ABC affiliate (ch ...

, south to Kapp Fie.

After rounding Kapp Fie, the coast along the south side is known as Vogtkysten. The westernmost part of it is the long shore of Sjøelefantstranda.

Off Catoodden, on the south-western corner, lies Larsøya

Larsøya, sometimes anglicized as Lars Island, is a rocky island, less than long, which lies just off the southwestern extremity of the island of Bouvetøya in the South Atlantic Ocean. It was first roughly charted in 1898 by a German expeditio ...

, the only island of any size off Bouvetøya. The western coast from Catoodden north to Nyrøysa, is known as Esmarchkysten. Midway up the coast lies Norvegiaodden ( Kapp Norvegia) and off it the skerries of Bennskjæra.

Ninety-three percent of the island is covered by glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

s, giving it a domed shape. The summit region of the island is Wilhelmplatået, slightly to the west of the island's center. The plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ...

is across and surrounded by several peaks. The tallest is Olavtoppen, above mean sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance ( height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as '' orthometric heights''.

Th ...

(AMSL), followed by Lykketoppen ( AMSL) and Mosbytoppane ( AMSL). Below Wilhelmplatået is the main caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

responsible for creating the island. The last eruption

Several types of volcanic eruptions—during which lava, tephra (ash, lapilli, volcanic bombs and volcanic blocks), and assorted gases are expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure—have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often ...

took place 2000 BCE, producing a lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or un ...

flow at Kapp Meteor. The volcano is presumed to be in a declining state. The temperature below the surface is .

The island's total coastline is . Landing on the island is very difficult, as it normally experiences high seas and features a steep coast. During the winter, it is surrounded by pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fasten ...

. The Bouvet Triple Junction is located west of Bouvet Island. It is a triple junction

A triple junction is the point where the boundaries of three tectonic plates meet. At the triple junction each of the three boundaries will be one of three types – a ridge (R), trench (T) or transform fault (F) – and triple junctions can ...

between the South American Plate, the African Plate

The African Plate is a major tectonic plate that includes much of the continent of Africa (except for its easternmost part) and the adjacent oceanic crust to the west and south. It is bounded by the North American Plate and South American Plate ...

and the Antarctic Plate

The Antarctic Plate is a tectonic plate containing the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau, and some remote islands in the Southern Ocean and other surrounding oceans. After breakup from Gondwana (the southern part of the superconti ...

, and of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the Southwest Indian Ridge and the American–Antarctic Ridge.

Climate

The island is located south of theAntarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. Antarctic waters pr ...

, giving it a marine Antarctic climate

The climate of Antarctica is the coldest on Earth. The continent is also extremely dry (it is a desert), averaging of precipitation per year. Snow rarely melts on most parts of the continent, and, after being compressed, becomes the glacier ic ...

dominated by heavy clouds and fog. It experiences a mean temperature of , with January average of and September average of . The monthly high mean temperatures fluctuate little through the year. The peak temperature of was recorded in March 1980, caused by intense sun radiation. Spot temperatures as high as have been recorded in sunny weather on rock faces. The island predominantly experiences a weak west wind

A west wind is a wind that originates in the west and blows in an eastward direction.

Mythology and Literature

In European tradition, it has usually been considered the mildest and most favorable of the directional winds.

In Greek mythology, ...

. In spite of these severe climate conditions, Bouvet Island actually is located four degrees of latitude closer to the equator than the southernmost tip of Norway, which is located at 58°N. Its latitude – by analogy to Scandinavia – is instead similar to southern Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

.

Nature

The harsh climate and ice-bound terrain limits non-animal life to

The harsh climate and ice-bound terrain limits non-animal life to fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

( ascomycetes including symbiotic lichens

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.non-vascular plant

Non-vascular plants are plants without a vascular system consisting of xylem and phloem. Instead, they may possess simpler tissues that have specialized functions for the internal transport of water.

Non-vascular plants include two distantly rel ...

s ( mosses and liverworts). The flora are representative for the maritime Antarctic and are phytogeographically

Phytogeography (from Greek φυτόν, ''phytón'' = "plant" and γεωγραφία, ''geographía'' = "geography" meaning also distribution) or botanical geography is the branch of biogeography that is concerned with the geographic distribution o ...

similar to those of the South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

and South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of Antarctic islands with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the nearest point of the South Orkney Islands. By the Antarctic Treaty of 1 ...

. Vegetation is limited because of the ice cover, although snow algae

Snow algae are a group of freshwater micro-algae which grow in the alpine and polar regions of the earth. These algae have been observed to come in a variety of colors associated with both the individual species, stage of life or topography/geogra ...

are recorded. The remaining vegetation is located in snow-free areas such as nunatak ridges and other parts of the summit plateau, the coastal cliffs, capes and beaches. At Nyrøysa, five species of moss, six ascomycetes (including five lichens), and twenty algae have been recorded. Most snow-free areas are so steep and subject to frequent avalanche

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down a slope, such as a hill or mountain.

Avalanches can be set off spontaneously, by such factors as increased precipitation or snowpack weakening, or by external means such as humans, animals, and eart ...

s that only crustose

Crustose is a habit of some types of algae and lichens in which the organism grows tightly appressed to a substrate, forming a biological layer. ''Crustose'' adheres very closely to the substrates at all points. ''Crustose'' is found on rocks ...

lichens and algal formations are sustainable. There are six endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

ascomycetes, three of which are lichenized.

The island has been designated as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of its importance as a breeding ground for

The island has been designated as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of its importance as a breeding ground for seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s. In 1978–1979 there were an estimated 117,000 breeding penguins

Penguins (order Sphenisciformes , family Spheniscidae ) are a group of aquatic flightless birds. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is found north of the Equator. Highly adapt ...

on the island, consisting of macaroni penguin

The macaroni penguin (''Eudyptes chrysolophus'') is a species of penguin found from the Subantarctic to the Antarctic Peninsula. One of six species of crested penguin, it is very closely related to the royal penguin, and some authorities consid ...

and, to a lesser extent, chinstrap penguin and Adélie penguin, although these were only estimated to be 62,000 in 1989–1990. Nyrøysa is the most important colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state' ...

for penguins, supplemented by Posadowskybreen, Kapp Circoncision, Norvegiaodden and across from Larsøya. Southern fulmar

The southern fulmar (''Fulmarus glacialoides'') is a seabird of the Southern Hemisphere. Along with the northern fulmar, ''F. glacialis'', it belongs to the fulmar genus ''Fulmarus'' in the family Procellariidae, the true petrels. It is also kno ...

is by far the most common non-penguin bird with 100,000 individuals. Other breeding seabirds consist of Cape petrel, Antarctic prion

The Antarctic prion (''Pachyptila desolata'') also known as the dove prion, or totorore in Māori, is the largest of the prions, a genus of small petrels of the Southern Ocean.

Taxonomy

The Antarctic prion was formally described in 1789 by ...

, Wilson's storm petrel

Wilson's storm petrel (''Oceanites oceanicus''), also known as Wilson's petrel, is a small seabird of the austral storm petrel family Oceanitidae. It is one of the most abundant bird species in the world and has a circumpolar distribution mainly ...

, black-bellied storm petrel, subantarctic skua, southern giant petrel, snow petrel

The snow petrel (''Pagodroma nivea'') is the only member of the genus ''Pagodroma.'' It is one of only three birds that has been seen at the Geographic South Pole, along with the Antarctic petrel and the south polar skua, which have the most s ...

, slender-billed prion

The slender-billed prion (''Pachyptila belcheri'') or thin-billed prion, is a species of petrel, a seabird in the family Procellariidae. It is found in the southern oceans.

Taxonomy

The slender-billed prion was species description, formally ...

and Antarctic tern

The Antarctic tern (''Sterna vittata'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. It ranges throughout the southern oceans and is found on small islands around Antarctica as well as on the shores of the mainland. Its diet consists primarily of small fis ...

. Kelp gull

The kelp gull (''Larus dominicanus''), also known as the Dominican gull, is a gull that breeds on coasts and islands through much of the Southern Hemisphere. The nominate ''L. d. dominicanus'' is the subspecies found around South America, part ...

is thought to have bred on the island earlier. Non-breeding birds which can be found on the island include the king penguin

The king penguin (''Aptenodytes patagonicus'') is the second largest species of penguin, smaller, but somewhat similar in appearance to the emperor penguin. There are two subspecies: ''A. p. patagonicus'' and ''A. p. halli''; ''patagonicus'' ...

, wandering albatross

The wandering albatross, snowy albatross, white-winged albatross or goonie (''Diomedea exulans'') is a large seabird from the family Diomedeidae, which has a circumpolar range in the Southern Ocean. It was the last species of albatross to be desc ...

, black-browed albatross

The black-browed albatross (''Thalassarche melanophris''), also known as the black-browed mollymawk,Robertson, C. J. R. (2003) is a large seabird of the albatross family Diomedeidae; it is the most widespread and common member of its family.

T ...

, Campbell albatross

The Campbell albatross (''Thalassarche impavida'') or Campbell mollymawk, is a medium-sized mollymawk in the albatross family. It breeds only on Campbell Island and the associated islet of Jeanette Marie, in a small New Zealand island group in t ...

, Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross

The Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross (''Thalassarche chlororhynchos'') is a large seabird in the albatross family Diomedeidae.

This small mollymawk was once considered conspecific with the Indian yellow-nosed albatross and known as the yellow-no ...

, sooty albatross, light-mantled albatross

The light-mantled albatross (''Phoebetria palpebrata'') also known as the grey-mantled albatross or the light-mantled sooty albatross, is a small albatross in the genus ''Phoebetria'', which it shares with the sooty albatross. The light-mantled a ...

, northern giant petrel

The northern giant petrel (''Macronectes halli''), also known as Hall's giant petrel, is a large predatory seabird of the southern oceans. Its distribution overlaps broadly, but is slightly north of, the similar southern giant petrel (''Macrone ...

, Antarctic petrel, blue petrel

The blue petrel (''Halobaena caerulea'') is a small seabird in the shearwater and petrel family, Procellariidae. This small petrel is the only member of the genus ''Halobaena'', but is closely allied to the prions. It is distributed across the So ...

, soft-plumaged petrel, Kerguelen petrel, white-headed petrel, fairy prion

The fairy prion (''Pachyptila turtur'') is a small seabird with the standard prion plumage of blue-grey upperparts with a prominent dark "M" marking and white underneath. The sexes are alike. This is a small prion of the low subantarctic and sub ...

, white-chinned petrel, great shearwater

The great shearwater (''Ardenna gravis'') is a large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. It breeds colonially on rocky islands in the south Atlantic. Outside the breeding season it ranges widely in the Atlantic.

Taxonomy

The great s ...

, common diving petrel, south polar skua

The south polar skua (''Stercorarius maccormicki'') is a large seabird in the skua family, Stercorariidae. An older name for the bird is MacCormick's skua, after explorer and naval surgeon Robert McCormick, who first collected the type specimen. ...

and parasitic jaeger.

The only non-bird vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with c ...

s on the island are seals, specifically the southern elephant seal

The southern elephant seal (''Mirounga leonina'') is one of two species of elephant seals. It is the largest member of the clade Pinnipedia and the order Carnivora, as well as the largest extant marine mammal that is not a cetacean. It gets its ...

and Antarctic fur seal

The Antarctic fur seal (''Arctocephalus gazella''), is one of eight seals in the genus ''Arctocephalus'', and one of nine fur seals in the subfamily Arctocephalinae. Despite what its name suggests, the Antarctic fur seal is mostly distributed i ...

, which both breed on the island. In 1998–1999, there were 88 elephant seal pups and 13,000 fur seal pups at Nyrøysa. Southern right whale, humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hu ...

, fin whale

The fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus''), also known as finback whale or common rorqual and formerly known as herring whale or razorback whale, is a cetacean belonging to the parvorder of baleen whales. It is the second-longest species of ce ...

, southern right whale dolphin

The southern right whale dolphin (''Lissodelphis peronii'') is a small and slender species of cetacean, found in cool waters of the Southern Hemisphere. It is one of two species of right whale dolphin (genus ''Lissodelphis''). This genus is char ...

, hourglass dolphin

The hourglass dolphin (''Lagenorhynchus cruciger'') is a small dolphin in the family Delphinidae that inhabits offshore Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters. It is commonly seen from ships crossing the Drake Passage, but has a circumpolar dis ...

, and killer whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white ...

are seen in the surrounding waters.

Politics and government

Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addi ...

, which are subject to the Antarctic Treaty System, Bouvetøya is not disputed. The dependency status entails that the island is not part of the Kingdom of Norway, but is still under Norwegian sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

. This implies that the island can be ceded without violating the first article of the Constitution of Norway. Norwegian administration of the island is handled by the Polar Affairs Department of the Ministry of Justice and the Police, located in Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population ...

.

The annexation of the island is regulated by the Dependency Act of 24 March 1933. It establishes that Norwegian criminal law, private law and procedural law

Procedural law, adjective law, in some jurisdictions referred to as remedial law, or rules of court, comprises the rules by which a court hears and determines what happens in civil, lawsuit, criminal or administrative proceedings. The rules a ...

apply to the island, in addition to other laws that explicitly state they are valid on the island. It further establishes that all land belongs to the state, and prohibits the storage and detonation of nuclear products.

Bouvet Island has been designated with the ISO 3166-2

ISO 3166-2 is part of the ISO 3166 standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and defines codes for identifying the principal subdivisions (e.g., provinces or states) of all countries coded in ISO 3166-1. The ...

code BV and was subsequently awarded the country code

Country codes are short alphabetic or numeric geographical codes (geocodes) developed to represent countries and dependent areas, for use in data processing and communications. Several different systems have been developed to do this. The term ...

top-level domain

A top-level domain (TLD) is one of the domains at the highest level in the hierarchical Domain Name System of the Internet after the root domain. The top-level domain names are installed in the root zone of the name space. For all domains in ...

.bv

.bv is the Internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) reserved for the uninhabited Norwegian dependent territory of Bouvet Island. The domain name registry and sponsor is Norid, but is not open for registration. was designated on 21 Augus ...

on 21 August 1997. The domain is managed by Norid but is not in use.

The exclusive economic zone surrounding the island covers an area of .In fiction

* The island figures prominently in the book ''A Grue of Ice'' (1962), an adventure novel byGeoffrey Jenkins

Geoffrey Ernest Jenkins (16 June 1920 – 7 November 2001) was a South African journalist, novelist and screenwriter. His wife Eve Palmer, with whom he collaborated on several works, wrote numerous non-fiction works about Southern Africa.

Earl ...

, based on Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying approximately from Cape Town in South Africa, from Saint Helena a ...

, Bouvet, and the mythical Thompson Island.

* Bouvet is the setting of the 2004 film ''Alien vs. Predator

''Alien vs. Predator'' (also known as ''Aliens versus Predator'' and ''AVP'') is a science-fiction action horror

media franchise created by comic book writers Randy Stradley and Chris Warner. The series is a crossover between, and part of, th ...

'', in which it is referred to using its Norwegian name "Bouvetøya".

See also

* Bolle Bay *List of islands of Norway

This is a list of islands of Norway sorted by name. For a list sorted by area, see List of islands of Norway by area.

A

* Alden

* Aldra

* Algrøy

* Alsta

* Altra

* Anda

* Andabeløya

* Andørja

* Andøya, Vesterålen

* Andøya, Agder

* ...

* List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

* Morrell Reef

Morrell Reef () is a reef reported to lie close off the southeast coast of Bouvetøya, about northward of Cape Fie. It was first charted in 1898 by a German expedition under Carl Chun, and was recharted in December 1927 by a Norwegian expediti ...

* Norris Reef

* Norvegia Rock

* Røver Anchorage Røver Anchorage () is an open anchorage along the southwest coast of Bouvetøya, approximately midway between Norvegia Point and Lars Island. The anchorage was used in December 1927 by the ''Norvegia'', the vessel of the Norwegian expedition und ...

* Spiess Rocks

Explanatory notes

References

External links

The Most Remote Island in the World

��''Sometimes Interesting'', 11 November 2012

Amateur Radio DX Pedition to Bouvet Island 3Y0Z

Bouvet Island, the most remote island in the World

��Random-Times.com, June 2018' {{Authority control Antarctic region 1920s establishments in Antarctica Dependencies of Norway Important Bird Areas of Antarctica Important Bird Areas of Norwegian overseas territories Important Bird Areas of subantarctic islands Inactive volcanoes Islands of the South Atlantic Ocean Mid-Atlantic Ridge Nature reserves in Norway Penguin colonies Polygenetic shield volcanoes Ridge volcanoes Seabird colonies Seal hunting States and territories established in 1928 Uninhabited islands of Norway Volcanoes of Norway Volcanoes of the Southern Ocean