Bonar Law on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British

James Law was the minister for several isolated townships, and had to travel between them by horse, boat and on foot. To supplement the family income, he bought a small farm on the

James Law was the minister for several isolated townships, and had to travel between them by horse, boat and on foot. To supplement the family income, he bought a small farm on the

Law's chance to make his mark came with the issue of

Law's chance to make his mark came with the issue of  The speech and its ideas split the

The speech and its ideas split the

However, the crisis over the Budget had highlighted a long-standing constitutional question: should the House of Lords be able to overturn bills passed by the House of Commons? The Liberal government introduced a bill in February 1910 which would prevent the House of Lords vetoing finance bills, and would force them to pass any bill which had been passed by the Commons in three sessions of Parliament.

This was immediately opposed by the Unionists, and both parties spent the next several months in a running battle over the bill. The Conservatives were led by

However, the crisis over the Budget had highlighted a long-standing constitutional question: should the House of Lords be able to overturn bills passed by the House of Commons? The Liberal government introduced a bill in February 1910 which would prevent the House of Lords vetoing finance bills, and would force them to pass any bill which had been passed by the Commons in three sessions of Parliament.

This was immediately opposed by the Unionists, and both parties spent the next several months in a running battle over the bill. The Conservatives were led by

On the coronation of

On the coronation of

During his early time as Conservative leader, the party's social policy was the most complicated and difficult to agree. In his opening speech as leader he said that the party would be one of principle, and would not be reactionary, instead sticking to their guns and holding firm policies. Despite this he left

During his early time as Conservative leader, the party's social policy was the most complicated and difficult to agree. In his opening speech as leader he said that the party would be one of principle, and would not be reactionary, instead sticking to their guns and holding firm policies. Despite this he left

Law again wrote to Strachey saying that he continued to feel this policy was the correct one, and only regretted that the issue was splitting the party at a time when unity was needed to fight the

Law again wrote to Strachey saying that he continued to feel this policy was the correct one, and only regretted that the issue was splitting the party at a time when unity was needed to fight the

In July 1912

In July 1912

Asquith responded with two notes, the first countering the Unionist claim that it would be acceptable for the King to dismiss Parliament or withhold assent of the Bill to force an election, and the second arguing that a Home Rule election would not prove anything, since a Unionist victory would only be due to other problems and scandals and would not assure supporters of the current government that Home Rule was truly opposed.

King George pressed for a compromise, summoning various political leaders to Balmoral Castle individually for talks. Law arrived on 13 September and again pointed out to the King his belief that if the Government continued to refuse an election fought over Home Rule and instead forced it on Ulster, the Ulstermen would not accept it and any attempts to enforce it would not be obeyed by the British Army.

By early October the King was pressuring the British political world for an all-party conference. Fending this off, Law instead met with senior party members to discuss developments. Law, Balfour,

Asquith responded with two notes, the first countering the Unionist claim that it would be acceptable for the King to dismiss Parliament or withhold assent of the Bill to force an election, and the second arguing that a Home Rule election would not prove anything, since a Unionist victory would only be due to other problems and scandals and would not assure supporters of the current government that Home Rule was truly opposed.

King George pressed for a compromise, summoning various political leaders to Balmoral Castle individually for talks. Law arrived on 13 September and again pointed out to the King his belief that if the Government continued to refuse an election fought over Home Rule and instead forced it on Ulster, the Ulstermen would not accept it and any attempts to enforce it would not be obeyed by the British Army.

By early October the King was pressuring the British political world for an all-party conference. Fending this off, Law instead met with senior party members to discuss developments. Law, Balfour,

At war's end, Law gave up the Exchequer for the less demanding

At war's end, Law gave up the Exchequer for the less demanding

online

* * * Blake, Robert. ''The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858–1923'' (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1955

online

* Charmley, John. ''A History of Conservative Politics, 1900–1996'' London: Macmillan, 1996) * Clark, Alan. ''The Tories: Conservatives and the Nation State, 1922–1997,'' (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1998) *

online free to borrow

* * * * *

online free to borrow

* * * * * * *

More about Andrew Bonar Law

on the Downing Street website.

The Bonar Law Papers

at the UK Parliamentary Archives

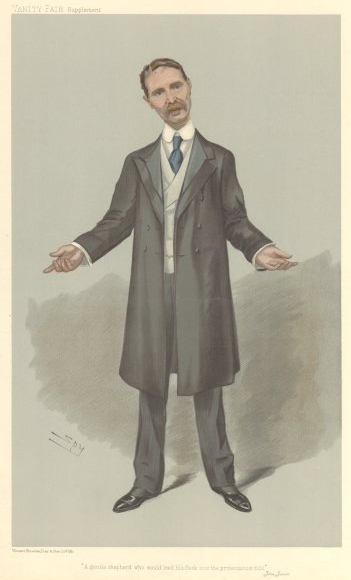

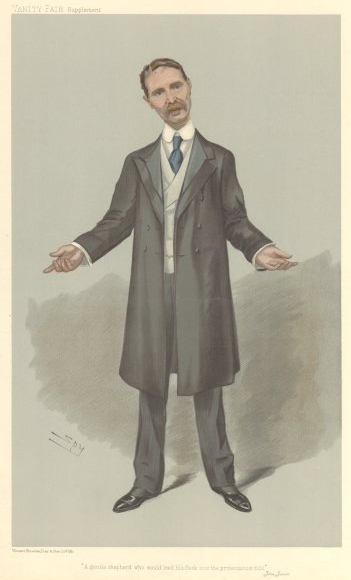

1903 illustrated article with photo of Bonar Law

* Stuart Ball

Bonar Law, Andrew

in

* * * ttps://archives.parliament.uk/collections/getrecord/GB61_BL Parliamentary Archives, The Bonar Law Papers {{DEFAULTSORT:Law, Bonar 1858 births 1923 deaths 20th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom British chess players British Presbyterians British Secretaries of State Deaths from cancer in England Canadian emigrants to the United Kingdom Chancellors of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom Scottish Tory MPs (pre-1912) Unionist Party (Scotland) MPs Deaths from esophageal cancer People educated at the High School of Glasgow Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK) Leaders of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Lords Privy Seal Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Glasgow constituencies People from Kent County, New Brunswick People from Helensburgh Politics of the London Borough of Southwark Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Rectors of the University of Glasgow UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 Conservative Party prime ministers of the United Kingdom Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Canadian people of Scottish descent Canadian people of Ulster-Scottish descent Secretaries of State for the Colonies Parliamentary Secretaries to the Board of Trade Burials at Westminster Abbey

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

(now a Canadian province). He was of Scottish and Ulster Scots descent and moved to Scotland in 1870. He left school aged sixteen to work in the iron industry, becoming a wealthy man by the age of thirty. He entered the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

at the 1900 general election, relatively late in life for a front-rank politician; he was made a junior minister, Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade The Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade in the United Kingdom was a member of Parliament assigned to assist the Board of Trade and its President with administration and liaison with Parliament. It replaced the Vice-President of the Board ...

, in 1902. Law joined the Shadow Cabinet in opposition after the 1906 general election. In 1911, he was appointed a Privy Councillor, before standing for the vacant party leadership. Despite never having served in the Cabinet and despite trailing third after Walter Long and Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

, Law became leader when the two front-runners withdrew rather than risk a draw splitting the party.

As Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, Law focused his attentions in favour of tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

and against Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

. His campaigning helped turn Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

attempts to pass the Third Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act of Parliament, Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home ...

into a three-year struggle eventually halted by the start of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, with much argument over the status of the six counties in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

which would later become Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, four of which were predominantly Protestant.

Law first held Cabinet office as Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, British Cabinet government minister, minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various British Empire, colonial dependencies.

Histor ...

in H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

's Coalition Government (May 1915 – December 1916). Upon Asquith's fall from power he declined to form a government, instead serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

in David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

's Coalition Government. He resigned on grounds of ill health early in 1921. In October 1922, with Lloyd George's Coalition having become unpopular with the Conservatives, he wrote a letter to the press giving only lukewarm support to the Government's actions over Chanak. After Conservative MPs voted to end the Coalition, he again became party leader and, this time, prime minister. Bonar Law won a clear majority at the 1922 general election, and his brief premiership saw negotiation with the United States over Britain's war loans. Seriously ill with throat cancer, Law resigned in May 1923, and died later that year. He was the fourth shortest-serving prime minister of the United Kingdom (211 days in office).

Early life and education

Andrew Bonar Law was born on 16 September 1858 in Kingston (now Rexton),New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

, to the Reverend James Law, a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, and his wife Eliza Kidston Law. He was of Scottish and Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

(mainly Ulster Scots) ancestry.R. J. Q. Adams

Ralph James Quincy Adams (born September 22, 1943) is an author and historian. He is professor of European and British history at Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public, land-grant, research univer ...

(1999) p. 3 At the time of his birth, New Brunswick was still a separate colony, as the Canadian confederation

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Canada, Dom ...

was not formed until 1867.

His mother originally wanted to name him after Robert Murray M'Cheyne

Robert Murray M'Cheyne (21 May 1813 – 25 March 1843) was a minister in the Church of Scotland from 1835 to 1843. He was born at Edinburgh on 21 May 1813, was educated at the university and at the Divinity Hall of his native city, and was ...

, a preacher she greatly admired, but as his older brother was already called Robert, he was instead named after Andrew Bonar

Andrew Alexander Bonar (29 May 1810 in Edinburgh – 30 December 1892 in Glasgow) was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, a contemporary and acquaintance of Robert Murray M'Cheyne and youngest brother of Horatius Bonar.

Life

He was b ...

, a biographer of M'Cheyne. Throughout his life he was always called Bonar by his family and close friends, never Andrew. He originally signed his name as A. B. Law, changing to A. Bonar Law in his thirties, and he was referred to as Bonar Law by the public as well.

James Law was the minister for several isolated townships, and had to travel between them by horse, boat and on foot. To supplement the family income, he bought a small farm on the

James Law was the minister for several isolated townships, and had to travel between them by horse, boat and on foot. To supplement the family income, he bought a small farm on the Richibucto River

The Richibucto River is a river in eastern New Brunswick, Canada which empties into the Northumberland Strait north of Richibucto. It is 80 kilometres long.Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

to look after the Law children. When James Law remarried in 1870, his new wife took over Janet's duties, and Janet decided to return home to Scotland. She suggested that Bonar Law should go with her, as the Kidston family were wealthier and better connected than the Laws, and Bonar would have a more privileged upbringing.Adams (1999) p. 6 Both James and Bonar accepted this, Bonar's father then accompanied him on his move to his aunt's. Bonar would never return to Kingston.

Law went to live at Janet's house in Helensburgh

Helensburgh (; gd, Baile Eilidh) is an affluent coastal town on the north side of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland, situated at the mouth of the Gareloch. Historically in Dunbartonshire, it became part of Argyll and Bute following local governm ...

, near Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. Her brothers Charles, Richard and William were partners in the family merchant bank Kidston & Sons, and as only one of them had married (and produced no heir) it was generally accepted that Law would inherit the firm, or at least play a role in its management when he was older.Adams (1999) p. 7 Immediately upon arriving from Kingston, Law began attending Gilbertfield House School, a preparatory school in Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

. In 1873, aged fourteen, he transferred to the High School of Glasgow

The High School of Glasgow is an independent, co-educational day school in Glasgow, Scotland. The original High School of Glasgow was founded as the choir school of Glasgow Cathedral in around 1124, and is the oldest school in Scotland, and the ...

, where with his good memory he showed a talent for languages, excelling in Greek, German and French. During this period, he first began to play chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to disti ...

– he would carry a board on the train between Helensburgh and Glasgow, challenging other commuters to matches. He eventually became a very good amateur player, and competed with internationally renowned chess masters.Adams (1999) p. 9 Despite his good academic record, it became obvious at Glasgow that he was better suited to business than to university, and when he was sixteen, Law left school to become a clerk at Kidston & Sons.

Business career

At Kidston & Sons, Law received a nominal salary, on the understanding that he would gain a "commercial education" from working there that would serve him well as a businessman. In 1885 the Kidston brothers decided to retire, and agreed to merge the firm with theClydesdale Bank

Clydesdale Bank ( gd, Banca Dhail Chluaidh) is a trading name used by Clydesdale Bank plc for its retail banking operations in Scotland.

In June 2018, it was announced that Clydesdale Bank's holding company CYBG would acquire Virgin Money for ...

.Adams (1999) p. 12

The merger would have left Law without a job and with poor career-prospects, but the retiring brothers found him a job with William Jacks

William Jacks (18 March 1841 – 9 August 1907) was a British ironmaster, author and Liberal politician.

Early life

Jacks was born at Cornhill-on-Tweed, near Coldstream, Northumberland the son Richard Jacks, a farmer and land steward, and his ...

, an iron merchant who had started pursuing a parliamentary career. The Kidston brothers lent Law the money to buy a partnership in Jacks' firm, and with Jacks himself no longer playing an active part in the company, Law effectively became the managing partner. Working long hours (and insisting that his employees did likewise), Law turned the firm into one of the most profitable iron merchants in the Glaswegian and Scottish markets.Adams (1999) p. 13

During this period Law became a "self-improver"; despite his lack of formal university education he sought to test his intellect, attending lectures given at Glasgow University

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

and joining the Glasgow Parliamentary Debating Association,Adams (1999) p.10 which adhered as closely as possible to the layout of the real Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

and undoubtedly helped Law hone the skills that served him so well in the political arena.Adams (1999) p. 11

By the time he was thirty Law had established himself as a successful businessman, and had time to devote to more leisurely pursuits. He remained an avid chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to disti ...

player, whom Andrew Harley called "a strong player, touching first-class amateur level, which he had attained by practice at the Glasgow Club in earlier days". Law also worked with the Parliamentary Debating Association and took up golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping wi ...

, tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball ...

and walking.Adams (1999) p. 16 In 1888 he moved out of the Kidston household and set up his own home at Seabank, with his sister Mary (who had earlier come over from Canada) acting as the housekeeper.

In 1890, Law met Annie Pitcairn Robley, the 24-year-old daughter of a Glaswegian merchant, Harrington Robley.Adams (1999) p. 17 They quickly fell in love, and married on 24 March 1891. Little is known of Law's wife, as most of her letters have been lost. It is known that she was much liked in both Glasgow and London, and that her death in 1909 hit Law hard; despite his relatively young age and prosperous career, he never remarried. The couple had six children: James Kidston (1893–1917), Isabel Harrington (1895–1969), Charles John (1897–1917), Harrington (1899–1958), Richard Kidston (1901–1980), and Catherine Edith (1905–1992).

The second son, Charlie, who was a lieutenant in the King's Own Scottish Borderers

The King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSBs) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Scottish Division. On 28 March 2006 the regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Scots, the Royal Highland Fusiliers (Princess Margaret's O ...

, was killed at the Second Battle of Gaza

The Second Battle of Gaza was fought on 17-19 April 1917, following the defeat of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) at the First Battle of Gaza in March, during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War. Gaza was defended by ...

in April 1917.Taylor (2007) p. 11 The eldest son, James, who was a captain in the Royal Fusiliers, was shot down and killed on 21 September 1917, and the deaths made Law even more melancholy and depressed than before.Taylor (2007) p.12 The youngest son, Richard, later served as a Conservative MP and minister. Isabel married Sir Frederick Sykes (in the early years of World War I she had been engaged for a time to the Australian war correspondent Keith Murdoch

Sir Keith Arthur Murdoch (12 August 1885 – 4 October 1952) was an Australian journalist, businessman and the father of Rupert Murdoch, the current Executive chairman for News Corporation and the chairman of Fox Corporation.

Early life

Murdoc ...

) and Catherine married, firstly, Kent Colwell and, much later, in 1961, The 1st Baron Archibald.Adams (1999) p. 293

Entry into politics

In 1897, Law was asked to become theConservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

candidate for the parliamentary seat of Glasgow Bridgeton. Soon after he was offered another seat, this one in Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown

Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown, representing parts of the city of Glasgow, Scotland, was a burgh constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1885 U ...

, which he took instead of Glasgow Bridgeton.Adams (1999) p. 18 Blackfriars was not a seat with high prospects attached; a working-class area, it had returned Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

MPs since it was created in 1884, and the incumbent, Andrew Provand

Andrew Dryburgh Provand (23 March 1838 – 18 July 1915) was a Scottish merchant strongly linked to Manchester; he was also a Liberal Party politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown from 1886 ...

, was highly popular. Although the election was not due until 1902, the events of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

forced the Conservative government to call a general election in 1900, later known as the khaki election

In Westminster systems of government, a khaki election is any national election which is heavily influenced by wartime or postwar sentiment. In the British general election of 1900, the Conservative Party government of Lord Salisbury was return ...

.Adams (1999) p.19 The campaign was unpleasant for both sides, with anti- and pro-war campaigners fighting vociferously, but Law distinguished himself with his oratory and wit. When the results came in on 4 October, Law was returned to Parliament with a majority of 1,000, overturning Provand's majority of 381. He immediately ended his active work at Jacks and Company (although he retained his directorship) and moved to London.Adams (1999) p. 20

Law initially became frustrated with the slow speed of Parliament compared to the rapid pace of the Glasgow iron market, and Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

recalled him saying to Chamberlain that "it was very well for men who, like myself had been able to enter the House of Commons young to adapt to a Parliamentary career, but if he had known what the House of Commons was he would never had entered at this stage".Taylor (2007) p. 8 He soon learnt to be patient, however, and on 18 February 1901 made his maiden speech. Replying to anti-Boer War MPs including David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, Law used his excellent memory to quote sections of Hansard

''Hansard'' is the traditional name of the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official print ...

back to the opposition which contained their previous speeches supporting and commending the policies they now denounced. Although lasting only fifteen minutes and not a crowd- or press-pleaser like the maiden speeches of F. E. Smith

Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, (12 July 1872 – 30 September 1930), known as F. E. Smith, was a British Conservative politician and barrister who attained high office in the early 20th century, in particular as Lord High Chan ...

or Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, it attracted the attention of the Conservative Party leaders.Adams (1999) p.21

Tariff reform

Law's chance to make his mark came with the issue of

Law's chance to make his mark came with the issue of tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

. To cover the costs of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

's Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

( Michael Hicks Beach) suggested introducing import taxes or tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s on foreign metal, flour and grain coming into Britain. Such tariffs had previously existed in Britain, but the last of these had been abolished in the 1870s because of the free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

movement. A duty was now introduced on imported corn.Adams (1999) p.22 The issue became "explosive", dividing the British political world, and continued even after Salisbury retired and was replaced as prime minister by his nephew, Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

.

Law took advantage of this, making his first major speech on 22 April 1902, in which he argued that while he felt a general tariff was unnecessary, an imperial customs union (which would put tariffs on items from outside the British Empire, instead of on every nation but Britain) was a good idea, particularly since other nations such as (Germany) and the United States had increasingly high tariffs.Adams (1999) p.23 Using his business experience, he made a "plausible case" that there was no proof that tariffs led to increases in the cost of living, as the Liberals had argued. Again his memory came into good use – when William Harcourt accused Law of misquoting him, Law was able to precisely give the place in Hansard

''Hansard'' is the traditional name of the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official print ...

where Harcourt's speech was to be found.

As a result of Law's proven experience in business matters and his skill as an economic spokesman for the government, Balfour offered him the position of Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade The Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade in the United Kingdom was a member of Parliament assigned to assist the Board of Trade and its President with administration and liaison with Parliament. It replaced the Vice-President of the Board ...

when he formed his government, which Law accepted,Adams (1999) p.24 and he was formally appointed on 11 August 1902.Taylor (2007) p. 9

As Parliamentary Secretary his job was to assist the President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

, Gerald Balfour. At the time the tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

controversy was brewing, led by the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

, an ardent tariff reformer who "declared war" on free trade, and who persuaded the Cabinet that the Empire should be exempted from the new corn duty. After returning from a speaking tour of South Africa in 1903, Chamberlain found that the new Chancellor of the Exchequer ( C. T. Ritchie) had instead abolished Hicks Beach's corn duty altogether in his budget. Angered by this, Chamberlain spoke at the Birmingham Town Hall on 15 May without the government's permission, arguing for an Empire-wide system of tariffs which would protect Imperial economies, forge the British Empire into one political entity and allow them to compete with other world powers.Adams (1999) p.25

The speech and its ideas split the

The speech and its ideas split the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

and its coalition ally the Liberal Unionist Party into two wings – the Free Fooders, who supported free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

, and the Tariff Reformers, who supported Chamberlain's tariff reforms. Law was a dedicated Tariff Reformer, but whereas Chamberlain dreamed of a new golden age for Britain, Law focused on more mundane and practical goals, such as a reduction in unemployment. L. S. Amery said that to Law, the tariff reform programme was "a question of trade figures and not national and Imperial policy of expansion and consolidation of which trade was merely the economic factor". Keith Laybourn

Keith Laybourn (born 13 March 1946) is Diamond Jubilee Professor of the University of Huddersfield and Professor of History. He is a British historian of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century specialising in labour history and the work ...

attributes Law's interest in tariff reform not only to the sound business practice that it represented but also that because of his place of birth "he was attracted by the Imperial tariff preference arrangements advocated by Joseph Chamberlain". Law's constituents in Blackfriars were not overly enthusiastic about tariff reform – Glasgow was a poor area at the time that had benefited from free trade.

In parliament, Law worked exceedingly hard at pushing for tariff reform, regularly speaking in the House of Commons and defeating legendary debaters such as Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, Charles Dilke and H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, former home secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

and later prime minister.Adams (1999) p.26 His speeches at the time were known for their clarity and common sense; Sir Ian Malcolm said that he made "the involved seem intelligible", and L. S. Amery said his arguments were "like the hammering of a skilled riveter, every blow hitting the nail on the head". Despite Law's efforts to forge consensus within the Conservatives, Balfour was unable to hold the two sides of his party together, and resigned as prime minister in December 1905, allowing the Liberals to form a government.

In opposition

The new prime minister, theLiberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1 ...

, immediately dissolved Parliament. Despite strong campaigning and a visit by Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

, Law lost his seat in the ensuing general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. In total the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

and Liberal Unionists lost 245 seats, leaving them with only 157 members of parliament, the majority of them tariff reformers.Adams (1999) p.28 Despite his loss, Law was at this stage such an asset to the Conservatives that an immediate effort was made to get him back into Parliament. The retirement of Frederick Rutherfoord Harris

Frederick Rutherfoord Harris (1 May 1856 – 1 September 1920) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) between 1900 and 1906.

Harris was born in Madras, India, where his father, George Anstruth ...

, MP for the safe Conservative seat of Dulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half of ...

, offered him a chance. Law was returned to Parliament in the ensuing by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

, increasing the Conservative majority to 1,279.

The party was struck a blow in July 1906, when two days after a celebration of his seventieth birthday, Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

suffered a stroke and was forced to retire from public life. He was succeeded as leader of the tariff reformers by his son Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

, who despite previous experience as Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

and enthusiasm for tariff reform was not as skilled a speaker as Law. As a result, Law joined Balfour's Shadow Cabinet as the principal spokesman for tariff reform.Adams (1999) p.31 The death of Law's wife on 31 October 1909 led him to work even harder, treating his political career not only as a job but as a coping strategy for his loneliness.

The People's Budget and the House of Lords

Campbell-Bannerman resigned as prime minister in April 1908 and was replaced byH. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

. In 1909, he and his Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

introduced the People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

, which sought through increased direct and indirect taxes to redistribute wealth and fund social reform programmes.Adams (1999) p.38 By parliamentary convention financial and budget bills are not challenged by the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, but in this case the predominantly Conservative and Liberal Unionist Lords rejected the bill on 30 April, setting off a constitutional crisis.

The Liberals called a general election for January 1910, and Law spent most of the preceding months campaigning up and down the country for other Unionist candidates and MPs, sure that his Dulwich seat was safe. He obtained an increased majority of 2,418.Adams (1999) p.39 The overall result was more confused: the Conservatives gained 116 seats, bringing their total to 273, but this was still less than the Liberal caucus, and produced a hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

, as neither had a majority of the seats (the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

, the Labour Party and the All-for-Ireland League took more than 120 seats in total). The Liberals remained in office with the support of the Irish Parliamentary Party. The Budget passed through the House of Commons a second time, and – as it now had an electoral mandate – was then approved by the House of Lords without a division.

However, the crisis over the Budget had highlighted a long-standing constitutional question: should the House of Lords be able to overturn bills passed by the House of Commons? The Liberal government introduced a bill in February 1910 which would prevent the House of Lords vetoing finance bills, and would force them to pass any bill which had been passed by the Commons in three sessions of Parliament.

This was immediately opposed by the Unionists, and both parties spent the next several months in a running battle over the bill. The Conservatives were led by

However, the crisis over the Budget had highlighted a long-standing constitutional question: should the House of Lords be able to overturn bills passed by the House of Commons? The Liberal government introduced a bill in February 1910 which would prevent the House of Lords vetoing finance bills, and would force them to pass any bill which had been passed by the Commons in three sessions of Parliament.

This was immediately opposed by the Unionists, and both parties spent the next several months in a running battle over the bill. The Conservatives were led by Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

and Lord Lansdowne, who headed the Conservatives in the House of Lords, while Law spent the time concentrating on the continuing problem of tariff reform. The lack of progress had convinced some senior Unionists that it would be a good idea to scrap tariff reform altogether. Law disagreed, successfully arguing that tariff reform "was the first constructive work of the onservative Party and that to scrap it would "split the Party from top to bottom".Adams (1999) p.40

With this success, Law returned to the constitutional crisis surrounding the House of Lords. The death of Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

on 6 May 1910 prompted the leaders of the major political parties to meet secretly in a "Truce of God" to discuss the Lords. The meetings were kept almost entirely secret: apart from the party representatives, the only people aware were F. E. Smith

Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, (12 July 1872 – 30 September 1930), known as F. E. Smith, was a British Conservative politician and barrister who attained high office in the early 20th century, in particular as Lord High Chan ...

, J. L. Garvin

James Louis Garvin CH (12 April 1868 – 23 January 1947) was a British journalist, editor, and author. In 1908, Garvin agreed to take over the editorship of the Sunday newspaper ''The Observer'', revolutionising Sunday journalism and restori ...

, Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Unionism in Ireland, Irish u ...

and Law.Adams (1999) p.41 The group met about twenty times at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

between June and November 1910, with the Unionists represented by Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

, Lord Cawdor, Lord Lansdowne and Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

. The proposal presented at the conference by David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

was a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

with members of both major parties in the Cabinet and a programme involving Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

, Poor Law reforms, imperial reorganisation and possibly tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

s. The Home Rule proposal would have made the United Kingdom a federation, with "Home Rule All Round" for Scotland, Ireland, and England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

. In the end the plans fell through: Balfour told Lloyd George on 2 November that the proposal would not work, and the conference was dissolved a few days later.

December 1910 general election

With the failure to establish a political consensus after the January 1910 general election, the Liberals called a second general election in December. The Conservative leadership decided that a good test of the popularity of thetariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

programme would be to have a prominent tariff reformer stand for election in a disputed seat. They considered Law a prime candidate, and after debating it for a month he guardedly agreed, enthusiastic about the idea but worried about the effect of a defeat on the Party.Adams (1999) p. 42 Law was selected as the candidate for Manchester North West, and became drawn into party debates about how strong a tariff reform policy should be put in their manifesto. Law personally felt that duties on foodstuffs should be excluded, something agreed to by Alexander Acland-Hood, Edward Carson and others at a meeting of the Constitutional Club

The Constitutional Club was a London gentlemen's club, now dissolved, which was established in 1883 and disbanded in 1979. Between 1886 and 1959 it had a distinctive red and yellow Victorian terracotta building, designed by Robert William Edis ...

on 8 November 1910, but they failed to reach a consensus and the idea of including or excluding food duties continued to be something that divided the party.Adams (1999) p.43

During the constitutional talks the Conservatives had demanded that, if the Lords' veto were removed, Irish Home Rule should only be permitted if approved by a UK-wide referendum. In response Lord Crewe, Liberal Leader in the Lords, had suggested sarcastically that tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

– a policy of questionable popularity because of the likelihood of increased prices on imported food – should also be submitted to a referendum. Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

now announced to a crowd of 10,000 at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

that after the coming election, a Conservative Government would indeed submit tariff reform to a referendum, something he described as "Bonar Law's proposal" or the "Referendum Pledge".Adams (1999) p.43–44 The suggestion was no more Law's than it was any of the dozens of Conservatives who had suggested this to Balfour, and his comment was simply an attempt to "pass the buck" and avoid the anger of Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

, who was furious that such an announcement had been made without consulting him or the party. While Law had written a letter to Balfour suggesting that a referendum would attract wealthy Conservatives, he said that "declaration would do no good with he working classand might damp enthusiasm of best workers".Adams (1999) p.45

Parliament was dissolved on 28 November, with the election to take place and polling to end by 19 December. The Conservative and Liberal parties were equal in strength, and with the continued support of the Irish Nationalists the Liberal Party remained in government. Law called his campaign in Manchester North West the hardest of his career; his opponent, George Kemp, was a war hero who had fought in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

and a former Conservative who had joined the Liberal party because of his disagreement with tariff reform.

In the end Law narrowly lost, with 5,114 votes to Kemp's 5,559, but the election turned him into a "genuine onservativehero", and he later said that the defeat did "more for him in the party than a hundred victories". In 1911, with the Conservative Party unable to afford him being out of Parliament, Law was elected in a March 1911 by-election for the safe Conservative seat of Bootle

Bootle (pronounced ) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton, Merseyside, England, which had a population of 51,394 in 2011; the wider Bootle (UK Parliament constituency), Parliamentary constituency had a population of 98,449.

Histo ...

. The Liberal attempt to curb the veto power of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

was now backed by a threat, if necessary, to create hundreds of Liberal peers. Law favoured surrender on pragmatic grounds, as a Unionist-dominated House of Lords would retain some ability to delay Liberal attempts to introduce Irish Home Rule, Welsh Disestablishment or electoral reforms gerrymandered to help the Liberal Party. In August 1911 enough Unionist peers abstained or voted in favour of the Liberal bill for it to pass as the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

, ending that particular dispute.

Leader of the Conservative Party

On the coronation of

On the coronation of George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

on 22 June 1911, Law was appointed as a Privy Councillor on the recommendation of the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

and Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

.Adams (1999) p.49 This was evidence of his seniority and importance within the Conservative Party. Balfour had become increasingly unpopular as Leader of the Conservative Party since the 1906 general election; tariff reformers saw his leadership as the reason for their electoral losses, and the "free fooders" had been alienated by Balfour's attempts to tame the zeal of the tariff reform faction. Balfour refused all suggestions of party reorganisation until a meeting of senior Conservatives led by Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

after the December 1910 electoral defeat issued an ultimatum demanding a review of party structure.

The defeat on the House of Lords issue turned a wing of the Conservative Party led by Henry Page Croft

Henry Page Croft, 1st Baron Croft (22 June 1881 – 7 December 1947) was a decorated British soldier and Conservative Party politician.

Early life and family

He was born at Fanhams Hall in Ware, Hertfordshire, England. He was the son of Ric ...

and his Reveille Movement, against Balfour. Leo Maxse

Leopold "Leo" James Maxse (11 November 1864 – 22 January 1932) was an English amateur tennis player and journalist and editor of the conservative British publication, ''National Review'', between August 1893 and his death in January 1932; he ...

began a Balfour Must Go campaign in his newspaper, the ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief i ...

'', and by July 1911 Balfour was contemplating resignation. Law himself had no problem with Balfour's leadership, and along with Edward Carson attempted to regain support for him.Adams (1999) p.57 By November 1911 it was accepted that Balfour was likely to resign, with the main competitors for the leadership being Law, Carson, Walter Long and Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

. When the elections began, Long and Chamberlain were the frontrunners; Chamberlain commanded the support of many tariff reformers, and Long that of the Irish Unionists. Carson immediately announced that he would not stand, and Law eventually announced that he would run for Leader, the day before Balfour resigned on 7 November.Adams (1999) p.59

At the beginning of the election Law held the support of no more than 40 of the 270 members of parliament; the remaining 230 were divided between Long and Chamberlain. Although Long believed he had the most MPs, his support was largely amongst backbencher

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of the " ...

s, and most of the whips and frontbenchers preferred Chamberlain.

With Long and Chamberlain almost neck-and-neck they called a meeting on 9 November to discuss the possibility of a deadlock. Chamberlain suggested that he would withdraw if this became a strong possibility, assuming Long did the same. Long, now concerned that his weak health would not allow him to survive the stress of party leadership, agreed. Both withdrew on 10 November, and on 13 November 232 MPs assembled at the Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a private members' club in St James's, London. It was the original home of the Conservative Party before the creation of Conservative Central Office. Membership of the club is by nomination and election only.

History

The ...

, and Law was nominated as leader by Long and Chamberlain. With the unanimous support of the MPs, Law became Leader of the Conservative Party despite never having sat in Cabinet. Law's biographer, Robert Blake, wrote that he was an unusual choice to lead the Conservatives as a Presbyterian Canadian-Scots businessman had just become the leader of "the Party of Old England, the Party of the Anglican Church and the country squire, the party of broad acres and hereditary titles".

As leader, Law first "rejuvenated the party machine", selecting newer, younger and more popular whips and secretaries, elevating F. E. Smith

Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, (12 July 1872 – 30 September 1930), known as F. E. Smith, was a British Conservative politician and barrister who attained high office in the early 20th century, in particular as Lord High Chan ...

and Lord Robert Cecil

Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, (14 September 1864 – 24 November 1958), known as Lord Robert Cecil from 1868 to 1923,As the younger son of a Marquess, Cecil held the courtesy title of "Lord". However, he ...

to the Shadow Cabinet and using his business acumen to reorganise the party, resulting in better relations with the press and local branches, along with the raising of a £671,000 "war chest" for the next general election: almost double that available at the previous one.

On 12 February 1912, he finally unified the two Unionist parties (Conservatives and Liberal Unionists) into the awkwardly named National Unionist Association of Conservative and Liberal-Unionist Organisations. From then on all were referred to as "Unionists" until the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

in 1922, after which they became Conservatives again (though the name "Unionist" continued in use in Scotland and Northern Ireland).

In Parliament, Law introduced the so-called "new style" of speaking, with harsh, accusatory rhetoric, which dominates British politics to this day.Adams (1999) p. 61 This was as a counter to Arthur Balfour, known for his "masterly witticisms", because the party felt they needed a warrior-like figure. Law did not particularly enjoy his tougher manner, and at the State Opening of Parliament in February 1912 apologised directly to Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

for his coming speech, saying, "I am afraid I shall have to show myself very vicious, Mr Asquith, this session. I hope you will understand." Law's "warrior king" figure helped unify the divided Conservatives into a single body, with him as the leader.

Social policy

During his early time as Conservative leader, the party's social policy was the most complicated and difficult to agree. In his opening speech as leader he said that the party would be one of principle, and would not be reactionary, instead sticking to their guns and holding firm policies. Despite this he left

During his early time as Conservative leader, the party's social policy was the most complicated and difficult to agree. In his opening speech as leader he said that the party would be one of principle, and would not be reactionary, instead sticking to their guns and holding firm policies. Despite this he left women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

alone, leaving the party unwhipped and saying that "the less part we take in this question the better".Adams (1999) p. 74 In terms of social reform (legislation to improve the conditions of the poor and working classes) Law was similarly unenthusiastic, believing that the area was a Liberal one, in which they could not successfully compete. His response to a request by Lord Balcarres

Earl of Balcarres is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in 1651 for Alexander Lindsay, 2nd Lord Balcarres. Since 1848, the title has been held jointly with the Earldom of Crawford, and the holder is also the hereditary clan chief

...

for a social programme was simply "As the iberal Partyrefuse to formulate their policy in advance we should be equally absolved".Adams (1999) p.75 His refusal to get drawn in may have actually strengthened his hold over Conservative MPs, many of whom were similarly uninterested in social reform.

In his first public speech as leader at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

on 26 January 1912 he listed his three biggest concerns: an attack on the Liberal government for failing to submit Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

to a referendum; tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

; and the Conservative refusal to let the Ulster Unionists be "trampled upon" by an unfair Home Rule bill.Adams (1999) p. 76 Both tariff reform and Ulster dominated his political work, with Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

saying that Law "once said to me that he cared intensely for only two things: Tariff Reform and Ulster; all the rest was only part of the game".

More tariff reform

After further review with members of his party, Law changed his initial beliefs ontariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

and accepted the full package, including duties on foodstuffs. On 29 February 1912 the entire Conservative parliamentary body (i.e. both MPs and peers) met at Lansdowne House, with Lord Lansdowne chairing.Adams (1999) p.79 Lansdowne argued that although the electorate might prefer the Conservative Party if they dropped food duties from their tariff reform plan, it would open them to accusations of bad faith and " poltroonery". Law endorsed Lansdowne's argument, pointing out that any attempt to avoid food duties would cause an internal party struggle and could only aid the Liberals, and that Canada, the most economically important colony and a major exporter of foodstuffs, would never agree to tariffs without British support of food duties.

Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, who opposed food duties, wrote to Law several weeks later suggesting they separate foodstuffs from tariff reform for the referendum. If the electorate liked food duties, they would vote for the entire package; if not, they did not have to.Adams (1999) p.80 Law replied arguing that it would be impossible to do so effectively, and that with the increasing costs of defence and social programmes it would be impossible to raise the necessary capital except by comprehensive tariff reform. He argued that a failure to offer the entire tariff reform package would split the Conservative Party down the middle, offending the tariff reform faction, and that if such a split took place "I could not possibly continue as leader".

Law postponed withdrawing the tariff reform "Referendum Pledge" because of the visit of Robert Borden

Sir Robert Laird Borden (June 26, 1854 – June 10, 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Canada from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during World War I.

Borde ...

, the newly elected Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority the elected Hou ...

, to London planned for July 1912. Meeting with Borden on his arrival, Law got him to agree to make a statement about the necessity of Imperial tariff reform, promising reciprocal agreements and saying that failure by London to agree tariff reform would result in an "irresistible pressure" for Canada to make a treaty with another nation, most obviously the United States.

Law decided that the November party conference was the perfect time to announce the withdrawal of the Referendum Pledge, and that Lord Lansdowne should do it, because he had been leader in the House of Lords when the pledge was made and because of his relatively low profile during the original tariff reform dispute.Adams (1999) p. 82 When the conference opened the British political world was febrile; on 12 November the opposition had narrowly defeated the government on an amendment to the Home Rule Bill, and the next evening, amidst hysterical shouting from the opposition, Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

attempted to introduce a motion reversing the previous vote. As the MPs filed out at the end of the day Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

began taunting the opposition, and in his anger Ronald McNeil hurled a copy of ''Standing Orders of the House'' at Churchill, hitting him on the head. Law refused to condemn the events, and it seems apparent that while he had played no part in organising them they ''had'' been planned by the party whips. As party leader, he was most likely aware of the plans even if he did not actively participate.

The conference was opened on 14 November 1912 by Lord Farquhar, who immediately introduced Lord Lansdowne.Adams (1999) p.83 Lansdowne revoked the Referendum Pledge, saying that as the government had failed to submit Home Rule to a referendum, the offer that tariff reform would also be submitted was null and void. Lansdowne promised that when the Unionists took office they would "do so with a free hand to deal with tariffs as they saw fit". Law then rose to speak, and in line with his agreement to let Lansdowne speak for tariff reform mentioned it only briefly when he said "I concur in every word which has fallen from Lord Lansdowne". He instead promised a reversal of several Liberal policies when the Unionists came to power, including the disestablishment of the Welsh Church, land taxes, and Irish Home Rule. The crowd "cheered themselves hoarse" at Law's speech.

However, the reaction from the party outside the conference hall was not a positive one. Law had not consulted the local constituency branches about his plan, and several important constituency leaders led by Archibald Salvidge

Sir Archibald Tutton James Salvidge (5 August 1863 – 11 December 1928) was an English politician, most notable for securing the political dominance of the Conservative Party in Liverpool through the use of the Working Men's Conservative ...

and Lord Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, (29 March 1799 – 23 October 1869, known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley) was a British statesman, three-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...