Bolesław I the Brave on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bolesław I the Brave ; cs, Boleslav Chrabrý; la, Boleslaus I rex Poloniae (17 June 1025), less often known as Bolesław the Great, was

Mieszko I died on 25 May 992. The contemporaneous

Mieszko I died on 25 May 992. The contemporaneous

Gallus Anonymus claimed that Bolesław was "gloriously raised to kingship by the emperor"''The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles'' (ch. 6.), p. 39. through these acts, but the Emperor's acts in Gniezno only symbolised that Bolesław received royal prerogatives, including the control of the Church in his realm. Radim Gaudentius was installed as the archbishop of the newly established

Gallus Anonymus claimed that Bolesław was "gloriously raised to kingship by the emperor"''The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles'' (ch. 6.), p. 39. through these acts, but the Emperor's acts in Gniezno only symbolised that Bolesław received royal prerogatives, including the control of the Church in his realm. Radim Gaudentius was installed as the archbishop of the newly established

Three candidates were competing with each other for the German crown after Otto III's death. One of them, Duke Henry IV of Bavaria, promised the

Three candidates were competing with each other for the German crown after Otto III's death. One of them, Duke Henry IV of Bavaria, promised the  Duke

Duke  In 1007, after learning about Bolesław's efforts to gain allies among Saxon nobles and giving refuge to the deposed duke of Bohemia, Oldřich, King Henry denounced the Peace of Poznań, which caused Bolesław's attack on the

In 1007, after learning about Bolesław's efforts to gain allies among Saxon nobles and giving refuge to the deposed duke of Bohemia, Oldřich, King Henry denounced the Peace of Poznań, which caused Bolesław's attack on the

Historians dispute the exact date of Bolesław's

Historians dispute the exact date of Bolesław's

According to

According to

The contemporaneous

The contemporaneous

Duke of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

from 992 to 1025, and the first King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

in 1025. He was also Duke of Bohemia between 1003 and 1004 as Boleslaus IV. A member of the ancient Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branch ...

, Bolesław was a capable monarch and a strong mediator in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

an affairs. He continued to proselytise Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholi ...

among his subjects and raised Poland to the rank of a kingdom, thus becoming the first Polish ruler to hold the title of ''rex'', Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for king.

The son of Mieszko I of Poland by his first wife Dobrawa of Bohemia, Bolesław ruled Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

already during the final years of Mieszko's reign. When the country became divided in 992, he banished his father's last consort, Oda of Haldensleben Oda of Haldensleben (c. 955/60 – 1023) was Duchess of the Polans by marriage to Mieszko I of Poland.

Life

Oda was the eldest child of Dietrich of Haldensleben, Margrave of the North March. She grew up in the monastery of Kalbe, near to Milde ...

, purged his half-brothers along with their adherents and successfully reunified Poland by 995. As a devout Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

, Bolesław supported the missionary endeavours of Adalbert of Prague

Adalbert of Prague ( la, Sanctus Adalbertus, cs, svatý Vojtěch, sk, svätý Vojtech, pl, święty Wojciech, hu, Szent Adalbert (Béla); 95623 April 997), known in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia by his birth name Vojtěch ( la, ...

and Bruno of Querfurt

Bruno of Querfurt ( 974 – 14 February or 9/14 March 1009), also known as ''Brun'' and ''Boniface'', was a Christian missionary bishop and martyr, who was beheaded near the border of Kievan Rus and Lithuania for trying to spread Christianity. H ...

. The martyrdom of Adalbert in 997 and Bolesław's successful attempt to ransom the bishop's remains, paying for their weight in gold, consolidated Poland's autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

.

At the Congress of Gniezno

The Congress of Gniezno ( pl, Zjazd gnieźnieński, german: Akt von Gnesen or ''Gnesener Übereinkunft'') was an amicable meeting between the Polish Duke Bolesław I the Brave and Emperor Otto III, which took place at Gniezno in Poland on 11 Ma ...

(11 March 1000), Emperor Otto III

Otto III (June/July 980 – 23 January 1002) was Holy Roman Emperor from 996 until his death in 1002. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto III was the only son of the Emperor Otto II and his wife Theophanu.

Otto III was crowned as King of ...

permitted the establishment of a Polish church structure with a Metropolitan See

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a t ...

at Gniezno

Gniezno (; german: Gnesen; la, Gnesna) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. One of the Piast dynasty's chief cities, ...

, independent from the Archbishopric of Magdeburg

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was a Roman Catholic archdiocese (969–1552) and Prince-Archbishopric (1180–1680) of the Holy Roman Empire centered on the city of Magdeburg on the Elbe River.

Planned since 955 and established in 968, the R ...

. Bishoprics

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

were also established in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

, Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, r ...

, and Kołobrzeg

Kołobrzeg ( ; csb, Kòlbrzég; german: Kolberg, ), ; csb, Kòlbrzég , is a port city in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in north-western Poland with about 47,000 inhabitants (). Kołobrzeg is located on the Parsęta River on the south coast ...

, and Bolesław formally repudiated paying tribute to the Empire. Following Otto's death in 1002, Bolesław fought a series of wars against Otto's cousin and heir, Henry II, ending in the Peace of Bautzen

The Peace of Bautzen (; ; ) was a treaty concluded on 30 January 1018, between Holy Roman Emperor Henry II and Bolesław I of Poland which ended a series of Polish-German wars over the control of Lusatia and Upper Lusatia (''Milzenerland'' or ...

(1018). In the summer of 1018, in one of his expeditions, Bolesław I captured Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, where he installed his son-in-law Sviatopolk I

Sviatopolk I Vladimirovich (''Sviatopolk the Accursed'', the ''Accursed Prince''; orv, Свѧтоплъкъ, translit=Svętoplŭkŭ; russian: Святополк Окаянный; uk, Святополк Окаянний; c. 980 – 1019) was the ...

as ruler. According to legend, Bolesław chipped his blade when striking Kiev's Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by t ...

. In honour of this legend, the ''Szczerbiec

Szczerbiec () is the ceremonial sword used in the coronations of most Polish monarchs from 1320 to 1764. It now is displayed in the treasure vault of the royal Wawel Castle in Kraków, as the only preserved part of the medieval Polish crown jewe ...

'' ("Jagged Sword") would later become the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

sword of Polish kings.

Bolesław is widely considered one of Poland's most accomplished Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branche ...

monarchs; he was an able strategist

A strategist is a person with responsibility for the formulation and implementation of a strategy. Strategy generally involves setting goals, determining actions to achieve the goals, and mobilizing resources to execute the actions. A strategy ...

and statesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political career at the national or international level.

Statesman or Statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

* ''The Statesman'' (Oregon), a ...

, who transformed Poland into an entity comparable to older Western monarchies and arguably raised it to the front rank of European states. Bolesław conducted successful military campaigns to the west, south and east of his realm, and conquered territories in modern-day Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

, Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

, Red Ruthenia

Red Ruthenia or Red Rus' ( la, Ruthenia Rubra; '; uk, Червона Русь, Chervona Rus'; pl, Ruś Czerwona, Ruś Halicka; russian: Червонная Русь, Chervonnaya Rus'; ro, Rutenia Roșie), is a term used since the Middle Ages fo ...

, Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''Meißen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

, Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

, and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

. He established the "Prince's Law" and sponsored the construction of churches, monasteries, military forts as well as waterway infrastructure. He also introduced the first Polish monetary unit

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general def ...

, the '' grzywna'', divided into 240 denarii

The denarius (, dēnāriī ) was the standard Roman silver coin from its introduction in the Second Punic War to the reign of Gordian III (AD 238–244), when it was gradually replaced by the antoninianus. It continued to be minted in very ...

,A. Czubinski, J. Topolski, ''Historia Polski'', Ossolineum, 1989. and minted his own coinage.

Early life

Bolesław was born in 966 or 967,Tymieniecki Kazimierz, ''Bolesław Chrobry''. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): ''Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja.'' Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. . Page 248 the first child of Mieszko I of Poland and his wife, theBohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n princess Dobrawa

Doubravka of Bohemia, Dobrawa ( cs, Doubravka Přemyslovna, pl, Dobrawa, Dąbrówka; ca. 940/45 – 977) was a Bohemian princess of the Přemyslid dynasty and by marriage Duchess of the Polans.

She was the daughter of Boleslaus I the Cruel, ...

. His ''Epitaph'', which was written in the middle of the , emphasised that Bolesław had been born to a "faithless" father and a "true-believing" mother, suggesting that he was born before his father's baptism. Bolesław was baptised shortly after his birth. He was named after his maternal grandfather, Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia

Boleslaus I ( cs, Boleslav I. Ukrutný) (915 – 972), a member of the Přemyslid dynasty, was ruler ('' kníže'', "duke") of the Duchy of Bohemia from 935 to his death. He is notorious for the murder of his elder brother Wenceslaus, through ...

. Not much is known about Bolesław's childhood. His ''Epitaph'' recorded that he underwent the traditional hair-cutting ceremony at the age of seven and a lock of his hair was sent to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. The latter act suggests that Mieszko wanted to place his son under the protection of the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

. Historian Tadeusz Manteuffel

Tadeusz Manteuffel or Tadeusz Manteuffel-Szoege (1902–1970) was a Polish historian, specializing in the medieval history of Europe.

Manteuffel was born in Rēzekne, Vitebsk Governorate, Russian Empire (now Latvia). His brothers were Leon ...

says that Bolesław needed that protection because his father had sent him to the court of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

in token of his allegiance to the emperor. However, historian Marek Kazimierz Barański notes that the claim that Bolesław was sent as a hostage to the imperial court is disputed.

Bolesław's mother, Dobrawa, died in 977; his widowed father married Oda of Haldensleben Oda of Haldensleben (c. 955/60 – 1023) was Duchess of the Polans by marriage to Mieszko I of Poland.

Life

Oda was the eldest child of Dietrich of Haldensleben, Margrave of the North March. She grew up in the monastery of Kalbe, near to Milde ...

who had already been a nun. Around that time, Bolesław became the ruler of Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

, through it is not exactly clear in what circumstances. Jerzy Strzelczyk

Prof. Dr. Hab. Jerzy Strzelczyk (born 24 December 1941 in Poznań) is Polish historian, professor at the Adam Mickiewicz University.

Works

* ''Po tamtej stronie Odry. Dzieje i upadek Słowian połabskich'', Warszawa 1968,

* ''Drzewianie poła ...

says that Bolesław received Lesser Poland from his father; Tadeusz Manteuffel states that he seized the province from his father with the local lords' support; and Henryk Łowmiański

Henryk Łowmiański (August 22, 1898 near Ukmergė - September 4, 1984 in Poznań) was a Polish historian and academic who was an authority on the early history of the Slavic and Baltic people. A researcher of the ancient history of Poland, Lithu ...

writes that his uncle, Boleslav II of Bohemia

Boleslaus II the Pious ( cs, Boleslav II. Pobožný pl, Bolesław II. Pobożny; c. 940 – 7 February 999), a member of the Přemyslid dynasty, was Duke of Bohemia from 972 until his death.

Life and reign

Boleslaus was an elder son of Duke B ...

, granted the region to him.

Accession and consolidation

Thietmar of Merseburg

Thietmar (also Dietmar or Dithmar; 25 July 9751 December 1018), Prince-Bishop of Merseburg from 1009 until his death, was an important chronicler recording the reigns of German kings and Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (Saxon) dynasty. Two ...

recorded that Mieszko left "his kingdom to be divided among many claimants", but Bolesław unified the country "with fox-like cunning"''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 4.58.), p. 192. and expelled his stepmother and half-brothers from Poland. Two Polish lords Odilien and Przibiwoj,''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 4.58.), p. 193. who had supported her and her sons, were blinded on Bolesław's order. Historian Przemysław Wiszewski says that Bolesław had already taken control of the whole of Poland by 992; Pleszczyński writes that this only happened in the last months of 995.

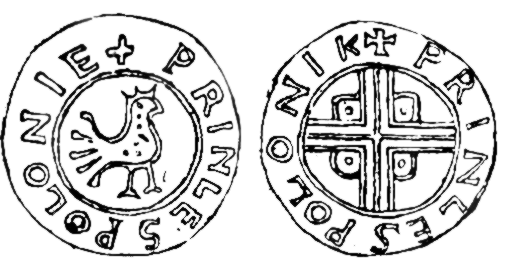

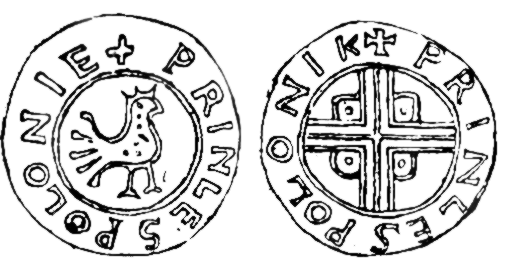

Bolesław's first coins were issued around 995. One of them bore the inscription Vencievlavus, showing that he regarded his mother's uncle Duke Wenceslaus I of Bohemia

Wenceslaus I ( cs, Václav I.; c. 1205 – 23 September 1253), called One-Eyed, was King of Bohemia from 1230 to 1253.

Wenceslaus was a son of Ottokar I of Bohemia and his second wife Constance of Hungary.

Marriage and children

In 1224, Wencesl ...

as the patron saint of Poland. Bolesław sent reinforcements to the Holy Roman Empire to fight against the Polabian Slavs

Polabian Slavs ( dsb, Połobske słowjany, pl, Słowianie połabscy, cz, Polabští slované) is a collective term applied to a number of Lechitic ( West Slavic) tribes who lived scattered along the Elbe river in what is today eastern Ger ...

in summer 992. Bolesław personally led a Polish army to assist the imperial troops in invading the land of the Abodrites

The Obotrites ( la, Obotriti, Abodritorum, Abodritos…) or Obodrites, also spelled Abodrites (german: Abodriten), were a confederation of medieval West Slavic tribes within the territory of modern Mecklenburg and Holstein in northern Germany ( ...

or Veleti

The Veleti, also known as Wilzi, Wielzians, and Wiltzes, were a group of medieval Lechitic tribes within the territory of Hither Pomerania, related to Polabian Slavs. They had formed together the Confederation of the Veleti, a loose monarchic c ...

in 995. During the campaign, he met the young German monarch, Otto III

Otto III (June/July 980 – 23 January 1002) was Holy Roman Emperor from 996 until his death in 1002. A member of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto III was the only son of the Emperor Otto II and his wife Theophanu.

Otto III was crowned as King of ...

.

Soběslav, the head of the Bohemian Slavník dynasty

The Slavniks/Slavníks or Slavnikids ( cs, Slavníkovci; german: Slawnikiden; pl, Sławnikowice) was a dynasty in the White Croatia during the 10th century. It is considered to be of White Croats origin. The center of the semi-independent princi ...

, also participated in the 995 campaign. Taking advantage of Soběslav's absence, Boleslav II of Bohemia invaded the Slavníks' domains and had most members of the family murdered. After learning of his kinsmen's fate, Soběslav settled in Poland. Bolesław gave shelter to him "for the sake of oběslav'sholy brother",''Life of Saint Adalbert Bishop of Prague and Martyr'' (ch. 25.), p. 165. Bishop Adalbert of Prague

Adalbert of Prague ( la, Sanctus Adalbertus, cs, svatý Vojtěch, sk, svätý Vojtech, pl, święty Wojciech, hu, Szent Adalbert (Béla); 95623 April 997), known in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia by his birth name Vojtěch ( la, ...

, according to the latter's hagiographies. Adalbert (known as Wojciech before his consecration) also came to Poland in 996, because Bolesław "was quite amicably disposed towards him".''Life of Saint Adalbert Bishop of Prague and Martyr'' (ch. 26.), p. 167. Adalbert's hagiographies suggest that the bishop and Bolesław closely cooperated. In early 997 Adalbert left Poland to proselytise among the Prussians, who had been invading the eastern borderlands of Bolesław's realm. However, the pagans murdered him on 23 April 997. Bolesław ransomed Adalbert's remains, paying its weight in gold, and buried it in Gniezno

Gniezno (; german: Gnesen; la, Gnesna) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. One of the Piast dynasty's chief cities, ...

. He sent parts of the martyr bishop's corpse to Emperor Otto III who had been Adalbert's friend.

Congress of Gniezno and its aftermath (999–1002)

Emperor Otto III held a synod in Rome where Adalbert was canonised on the emperor's request on 29 June 999. Before 2 December 999, Adalbert's brother, Radim Gaudentius, was consecrated "Saint Adalbert's archbishop". Otto III made a pilgrimage to Saint Adalbert's tomb in Gniezno, accompanied by Pope Sylvester II'slegate

Legate may refer to:

* Legatus, a higher ranking general officer of the Roman army drawn from among the senatorial class

:*Legatus Augusti pro praetore, a provincial governor in the Roman Imperial period

*A member of a legation

*A representative, ...

, Robert, in early 1000. Thietmar of Merseburg mentioned that it "would be impossible to believe or describe"''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 4.45.), p. 183. how Bolesław received the emperor and conducted him to Gniezno. A century later, Gallus Anonymus

''Gallus Anonymus'' ( Polonized variant: ''Gall '') is the name traditionally given to the anonymous author of ''Gesta principum Polonorum'' (Deeds of the Princes of the Poles), composed in Latin between 1112 and 1118.

''Gallus'' is generally rega ...

added that " rvelous and wonderful sights Bolesław set before the emperor when he arrived: the ranks first of the knights in all their variety, and then of the princes, lined up on a spacious plain like choirs, each separate unit set apart by the distinct and varied colors of its apparel, and no garment there was of inferior quality, but of the most precious stuff that might anywhere be found."''The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles'' (ch. 6.), p. 35.

Bolesław took advantage of the emperor's pilgrimage. After the Emperor's visit in Gniezno, Poland started to develop into a sovereign state, in contrast with Bohemia, which remained a vassal state, incorporated in the Kingdom of Germany

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom ( la, regnum Teutonicorum "kingdom of the Germans", "German kingdom", "kingdom of Germany") was the mostly Germanic-speaking East Frankish kingdom, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, espec ...

. Thietmar of Merseburg condemned Otto III for "making a lord out of a tributary"''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 5.10.), p. 212. in reference to the relationship between the Emperor and Bolesław. Gallus Anonymus emphasised that Otto III declared Bolesław "his brother and partner" in the Holy Roman Empire, also calling Bolesław "a friend and ally of the Roman people". The same chronicler mentioned that Otto III "took the imperial diadem from his own head and laid it upon the head of Bolesław in pledge of friendship"''The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles'' (ch. 6.), p. 37. in Gniezno. Bolesław also received "one of the nails from the cross of our Lord with the lance of St. Maurice

Saint Maurice (also Moritz, Morris, or Mauritius; ) was an Egyptian military leader who headed the legendary Theban Legion of Rome in the 3rd century, and is one of the favorite and most widely venerated saints of that martyred group. He is the ...

" from the Emperor.

Gallus Anonymus claimed that Bolesław was "gloriously raised to kingship by the emperor"''The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles'' (ch. 6.), p. 39. through these acts, but the Emperor's acts in Gniezno only symbolised that Bolesław received royal prerogatives, including the control of the Church in his realm. Radim Gaudentius was installed as the archbishop of the newly established

Gallus Anonymus claimed that Bolesław was "gloriously raised to kingship by the emperor"''The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles'' (ch. 6.), p. 39. through these acts, but the Emperor's acts in Gniezno only symbolised that Bolesław received royal prerogatives, including the control of the Church in his realm. Radim Gaudentius was installed as the archbishop of the newly established Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Gniezno

The Archdiocese of Gniezno ( la, Archidioecesis Gnesnensis, pl, Archidiecezja Gnieźnieńska) is the oldest Latin Catholic archdiocese in Poland, located in the city of Gniezno.Kołobrzeg

Kołobrzeg ( ; csb, Kòlbrzég; german: Kolberg, ), ; csb, Kòlbrzég , is a port city in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in north-western Poland with about 47,000 inhabitants (). Kołobrzeg is located on the Parsęta River on the south coast ...

, Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

and Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, r ...

—were set up. Bolesław had promised that Poland would pay Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence (or ''Denarii Sancti Petri'' and "Alms of St Peter") are donations or payments made directly to the Holy See of the Catholic Church. The practice began under the Saxons in England and spread through Europe. Both before and after the ...

to the Holy See to obtain the pope's sanction to the establishment of the new archdiocese. Unger, who had been the only prelate in Poland and was opposed to the creation of the archdiocese of Gniezno, was made bishop of Poznań

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, directly subordinated to the Holy See. However, Polish commoners only slowly adopted Christianity: Thietmar of Merseburg recorded that Bolesław forced his subjects with severe punishments to observe fasts and to refrain from adultery:

During the time the Emperor spent in Poland, Bolesław also showed off his affluence. At the end of the banquets, he "ordered the waiters and the cupbearers to gather the gold and silver vessels ... from all three days' coursis, that is, the cups and goblets, the bowls and plates and the drinking-horn

A drinking horn is the horn of a bovid used as a drinking vessel. Drinking horns are known from Classical Antiquity, especially the Balkans, and remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period i ...

s, and he presented them to the emperor as a toke of honor ... s servants were likewise told to collect the wall-hangings and the coverlets, the carpets and tablecloths and napkins and everything that had been provided for their needs and take them to the emperor's quarters", according to Gallus Anonymus. Thietmar of Merseburg recorded that Bolesław presented Otto III with a troop of "three hundred armoured warriors".''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 4.46.), p. 184. Bolesław also gave Saint Adalbert's arm to the Emperor.

After the meeting, Bolesław escorted Otto III to Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

in Germany where "they celebrated Palm Sunday with great festivity"''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 4.46.), p. 185. on 25 March 1000. A continuator of the chronicle of Adémar de Chabannes

Adémar de Chabannes (988/989 – 1034; also Adhémar de Chabannes) was a French/Frankish monk, active as a composer, scribe, historian, poet, grammarian and literary forger. He was associated with the Abbey of Saint Martial, Limoges, where he ...

recorded, decades after the events, that Bolesław also accompanied Emperor Otto from Magdeburg to Aachen where Otto III had Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

's tomb reopened and gave Charlemagne's golden throne to Bolesław.

An illustrated Gospel, made for Otto III around 1000, depicted four women symbolising Roma, Gallia, Germania and Sclavinia as doing homage to the Emperor who sat on his throne. Historian Alexis P. Vlasto writes that "Sclavinia" referred to Poland, proving that it was regarded as one of the Christian realms subjected to the Holy Roman Empire in accordance with Otto III's idea of ''Renovatio imperii''—the renewal of the Roman Empire based on a federal concept. Within that framework, Poland, along with Hungary, was upgraded to an eastern ''foederatus

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the '' socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign sta ...

'' of the Holy Roman Empire, according to historian Jerzy Strzelczyk

Prof. Dr. Hab. Jerzy Strzelczyk (born 24 December 1941 in Poznań) is Polish historian, professor at the Adam Mickiewicz University.

Works

* ''Po tamtej stronie Odry. Dzieje i upadek Słowian połabskich'', Warszawa 1968,

* ''Drzewianie poła ...

.

Coins struck for Bolesław shortly after his meeting with the emperor bore the inscription Gnezdun Civitas, showing that he regarded Gniezno as his capital. The name of Poland was also recorded on the same coins referring to the Princes Polonie . The title ''princeps'' was almost exclusively used in Italy around that time, suggesting that it also represented the Emperor's idea of the renewal of the Roman Empire. However, Otto's premature death on 23 January 1002 put an end to his ambitious plans. The contemporaneous Bruno of Querfurt

Bruno of Querfurt ( 974 – 14 February or 9/14 March 1009), also known as ''Brun'' and ''Boniface'', was a Christian missionary bishop and martyr, who was beheaded near the border of Kievan Rus and Lithuania for trying to spread Christianity. H ...

stated that "nobody lamented" the 22-year-old emperor's "death with greater grief than Bolesław".

In 1000 Bolesław issued a law prohibiting hunting beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers a ...

s and created a office called "Bobrowniczy" whose task was to enforce prince's ordinances.

Expansion (1002–1018)

Three candidates were competing with each other for the German crown after Otto III's death. One of them, Duke Henry IV of Bavaria, promised the

Three candidates were competing with each other for the German crown after Otto III's death. One of them, Duke Henry IV of Bavaria, promised the Margraviate of Meissen

The Margravate of Meissen (german: Markgrafschaft Meißen) was a medieval principality in the area of the modern German state of Saxony. It originally was a frontier march of the Holy Roman Empire, created out of the vast '' Marca Geronis'' ( Sax ...

to Bolesław in exchange for his assistance against Eckard I, Margrave of Meissen

Eckard I (''Ekkehard'';Rarely ''Ekkard'' or ''Eckhard''. Contemporary Latin variants to his name include ''Ekkihardus'', ''Eggihardus'', ''Eggihartus'', ''Heckihardus'', ''Egihhartus'', and ''Ekgihardus''. – 30 April 1002) was Margrave of Meiss ...

who was the most powerful contender. However, Eckard was murdered on 30 April 1002, which enabled Henry of Bavaria to defeat his last opponent, Herman II, Duke of Swabia. Fearing that Henry II would side with elements in the German Church hierarchy which were unfavorable towards Poland,Tymieniecki Kazimierz, ''Bolesław Chrobry''. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): ''Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja.'' Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. . Page 250 and taking advantage of the chaos that followed Margrave Eckard's death and Henry of Bavaria's conflict with Henry of Schweinfurt

Henry of Schweinfurt (''de Suinvorde''; – 18 September 1017) was the Margrave of the Nordgau from 994 until 1004. He was called the "glory of eastern Franconia" by his own cousin, the chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg.

Henry was the son of ...

, Bolesław invaded Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

and Meissen. He "seized Margrave Gero's march as far as the river Elbe",''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 5.9.), p. 211. and also Bautzen

Bautzen () or Budyšin () is a hill-top town in eastern Saxony, Germany, and the administrative centre of the district of Bautzen. It is located on the Spree river. In 2018 the town's population was 39,087. Until 1868, its German name was ''Budi ...

, Strehla

Strehla ( hsb, Strjela) is a small town in the district of Meißen, Saxony, Germany. It is located on the river Elbe, north of Riesa. This place name means ''arrow'' in Sorbian. Strehla includes the following subdivisions:

*Forberge

*Görzig/ ...

and Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''Meißen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

. At the end of July, he participated at a meeting of the Saxon lords where Henry of Bavaria, who had meanwhile been crowned king of Germany, only confirmed Bolesław's possession of Lusatia, and granted Meissen to Margrave Eckard's brother, Gunzelin, and Strehla to Eckard's oldest son, Herman

Herman may refer to:

People

* Herman (name), list of people with this name

* Saint Herman (disambiguation)

* Peter Noone (born 1947), known by the mononym Herman

Places in the United States

* Herman, Arkansas

* Herman, Michigan

* Herman, Min ...

. The relationship between King Henry and Bolesław became tense after assassins tried to murder Bolesław in Merseburg, because he accused the king of conspiracy against him. In retaliation, he seized and burned Strehla and took the inhabitants of the town into captivity.

Duke

Duke Boleslaus III of Bohemia

Boleslaus III ( – 1037), called the Red ( cs, Boleslav III. Ryšavý; to denote a "red-haired" individual) or the Blind, a member of the Přemyslid dynasty, was duke of Bohemia from 999 until 1002 and briefly again during the year 1003. He wa ...

was dethroned and the Bohemian lords made Vladivoj, who had earlier fled to Poland, duke in 1002. The Czech historian Dušan Třeštík

Dušan Třeštík (1 August 1933 – 23 August 2007) was a Czech historian. He specialized in medieval history ( Dark Ages (500–1000)) of the Czech lands and theory of history.

Třeštík was born in 1933 in Sobědruhy, now a part of the city ...

writes that Vladivoj seized the Bohemian throne with Bolesław's assistance. After Vladivoj died in 1003, Bolesław invaded Bohemia and restored Boleslaus III who had many Bohemian noblemen murdered. The Bohemian lords who survived the massacre "secretly sent representatives" to Bolesław, asking "him to rescue them from fear of the future",''The'' Chronicon ''of Thietmar of Merseburg'' (ch. 5.30.), p. 225. according to Thietmar of Merseburg. Bolesław invaded Bohemia and had Boleslaus III blinded. He entered Prague in March 1003 where the Bohemian lords proclaimed him duke.Tymieniecki Kazimierz, ''Bolesław Chrobry''. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): ''Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja.'' Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. . Page 251 King Henry sent his envoys to Prague, demanding that Bolesław take an oath of loyalty and pay tribute to him, but Bolesław refused to obey. He also allied himself with the king's opponents, including Henry of Schweinfurt to whom he sent reinforcements. King Henry defeated Henry of Schweinfurt, forcing him to flee to Bohemia in August 1003. Bolesław invaded the Margraviate of Meissen, but Margrave Gunzelin refused to surrender his capital. It is also likely that Polish forces took control of Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

and the northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

(present-day mostly Slovakia) in 1003 as well. The proper conquest date of the Hungarian territories is 1003 or 1015 and this area stayed a part of Poland until 1018.

King Henry allied himself with the pagan Lutici

The Lutici or Liutizi (known by various spelling variants) were a federation of West Slavic Polabian tribes, who between the 10th and 12th centuries lived in what is now northeastern Germany. Four tribes made up the core of the federation: th ...

, and broke into Lusatia in February 1004, but heavy snows forced him to withdraw. He invaded Bohemia in August 1004, taking the oldest brother of the blinded Boleslaus III of Bohemia, Jaromír Jaromír, Jaromir, Jaroměr is a Slavic male given name.

Origin and meaning

Jaromír is a West Slavic given name composed of two stems ''jaro'' and ''mír''.

The meaning is not definite:

*Polish ''jary'' (archaic) = „spry, young, strong“; ''m ...

, with him. The Bohemians rose up in open rebellion and murdered the Polish garrisons in the major towns. Bolesław left Prague without resistance, and King Henry made Jaromír duke of Bohemia on 8 September. Bolesław's ally Soběslav died in this campaign.

During the next part of the offensive King Henry retook Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''Meißen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

and in 1005, his army advanced as far into Poland as the city of Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

where a peace treaty was signed.Thietmar of Merseburg, Thietmari merseburgiensis episcopi chronicon, 1018 According to the peace treaty Bolesław lost Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

and Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''Meißen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

and likely gave up his claim to the Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the mon ...

. Also in 1005, a pagan rebellion in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

overturned Bolesław's rule and resulted in the destruction of the newly established local bishopric.

In 1007, after learning about Bolesław's efforts to gain allies among Saxon nobles and giving refuge to the deposed duke of Bohemia, Oldřich, King Henry denounced the Peace of Poznań, which caused Bolesław's attack on the

In 1007, after learning about Bolesław's efforts to gain allies among Saxon nobles and giving refuge to the deposed duke of Bohemia, Oldřich, King Henry denounced the Peace of Poznań, which caused Bolesław's attack on the Archbishopric of Magdeburg

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was a Roman Catholic archdiocese (969–1552) and Prince-Archbishopric (1180–1680) of the Holy Roman Empire centered on the city of Magdeburg on the Elbe River.

Planned since 955 and established in 968, the R ...

as well as the re-occupation of the marches of Lusatia, though he stopped short of retaking Meissen. The German counter-offensive

In the study of military tactics, a counter-offensive is a large-scale strategic offensive military operation, usually by forces that had successfully halted the enemy's offensive, while occupying defensive positions.

The counter-offensive ...

began three years later (previously, Henry was occupied with rebellion in Flanders), in 1010, but it was of no significant consequence. In 1012, another ineffective campaign by archbishop Walthard

Walthard (or Waltaro) (died 12 August 1012) was the Archbishop of Magdeburg very briefly from June to August in 1012.

Walthard was the initial archiepiscopal candidate of the cathedral chapter on the death of Archbishop Giseler in 1004, but Kin ...

of Magdeburg was launched, as he died during that campaign and, consequently, his forces returned home. Later that year, Bolesław once again invaded Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

. Bolesław's forces pillaged and burned the city of Lubusz

Lebus ( pl, Lubusz) is a historic town in the Märkisch-Oderland District of Brandenburg, Germany. It is the administrative seat of '' Amt'' ("collective municipality") Lebus. The town, located on the west bank of the Oder river at the border wit ...

(Lebus). In 1013, a peace accord was signed at Merseburg

Merseburg () is a town in central Germany in southern Saxony-Anhalt, situated on the river Saale, and approximately 14 km south of Halle (Saale) and 30 km west of Leipzig. It is the capital of the Saalekreis district. It had a dioces ...

. As part of the treaty, Bolesław paid homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to King Henry for the March of Lusatia

The March or Margraviate of Lusatia (german: Mark(grafschaft) Lausitz) was as an eastern border march of the Holy Roman Empire in the lands settled by Polabian Slavs. It arose in 965 in the course of the partition of the vast '' Marca Geronis''. ...

(including the town of Bautzen) and Sorbian Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''Meißen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

as fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

s. A marriage of Bolesław's son Mieszko with Richeza of Lotharingia

Richeza of Lotharingia (also called ''Richenza'', ''Rixa'', ''Ryksa''; born about 995/1000 – 21 March 1063) was a member of the Ezzonen dynasty who became queen of Poland as the wife of Mieszko II Lambert. Her Polish marriage was arranged to s ...

, daughter of the Count Palatine

A count palatine (Latin ''comes palatinus''), also count of the palace or palsgrave (from German ''Pfalzgraf''), was originally an official attached to a royal or imperial palace or household and later a nobleman of a rank above that of an ord ...

Ezzo of Lotharingia

Lotharingia ( la, regnum Lotharii regnum Lothariense Lotharingia; french: Lotharingie; german: Reich des Lothar Lotharingien Mittelreich; nl, Lotharingen) was a short-lived medieval successor kingdom of the Carolingian Empire. As a more durable ...

and granddaughter of Emperor Otto II

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother (empr ...

, was also performed. During the brief period of peace on the western frontier that followed, Bolesław took part in a short campaign in the east, towards the Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

territories.

In 1014, Bolesław sent his son Mieszko to Bohemia in order to form an alliance with Duke Oldrich against Henry, by then crowned emperor. Oldrich imprisoned Mieszko and turned him over to Henry, who, however, released him in a gesture of good will after being pressured by Saxon nobles. Bolesław nonetheless refused to aid the emperor militarily in his Italian expedition. This led to imperial intervention in Poland and so in 1015 a war erupted once again. The war started out well for the emperor, as he was able to defeat the Polish forces at the Battle of Ciani. Once the imperial forces crossed the river Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

, Bolesław sent a detachment of Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

n knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

in a diversionary attack against the Eastern March of the empire. Soon after, the imperial army, having suffered a defeat near the Bóbr marshes, retreated from Poland without any permanent gains. After this event, Bolesław's forces took the initiative. Margrave Gero II of Meissen was defeated and killed during a clash with the Polish forces in late 1015. In 1015 and 1017, Bolesław I attacked the Eastern March and was defeated twice by Henry the Strong and his forces.Thietmar 2001, VIII, pp. 19, 61.Thietmar 2001, VIII, p. 9.

Later that year, Bolesław's son Mieszko was sent to plunder Meissen

Meissen (in German orthography: ''Meißen'', ) is a town of approximately 30,000 about northwest of Dresden on both banks of the Elbe river in the Free State of Saxony, in eastern Germany. Meissen is the home of Meissen porcelain, the Albre ...

. His attempt at conquering the city, however, failed. In 1017, Bolesław defeated Duke Henry V of Bavaria. In that same year, supported by his Slavic allies, Emperor Henry once again invaded Poland, albeit once again to very little effect. He did besiege the cities of Głogów

Głogów (; german: Glogau, links=no, rarely , cs, Hlohov, szl, Głogōw) is a city in western Poland. It is the county seat of Głogów County, in Lower Silesian Voivodeship (since 1999), and was previously in Legnica Voivodeship (1975–199 ...

and Niemcza

Niemcza (german: Nimptsch) is a town in Dzierżoniów County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in south-western Poland. It is the seat of the administrative district (gmina) called Gmina Niemcza.

The town lies on the Ślęza River, approximately e ...

, but was unable to conquer them. The imperial forces once again were forced to retreat, suffering significant losses. Taking advantage of the involvement of Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

troops, Bolesław ordered his son to invade Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, where Mieszko met very little resistance. On 30 January 1018, the Peace of Bautzen

The Peace of Bautzen (; ; ) was a treaty concluded on 30 January 1018, between Holy Roman Emperor Henry II and Bolesław I of Poland which ended a series of Polish-German wars over the control of Lusatia and Upper Lusatia (''Milzenerland'' or ...

was signed. The Polish ruler was able to keep the contested marches of Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

and Sorbian Meissen not as fiefs

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

, but as a part of Polish territory, and also received military aid in his expedition against Rus'. Also, Bolesław (then a widower) strengthened his dynastic bonds with the German nobility through his marriage with Oda, daughter of Margrave Eckard I of Meissen

Eckard I (''Ekkehard'';Rarely ''Ekkard'' or ''Eckhard''. Contemporary Latin variants to his name include ''Ekkihardus'', ''Eggihardus'', ''Eggihartus'', ''Heckihardus'', ''Egihhartus'', and ''Ekgihardus''. – 30 April 1002) was Margrave of Meiss ...

. The wedding took place four days later, on 3 February in the castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

of ''Cziczani'' (also ''Sciciani'', at the site of either modern Groß-Seitschen or Zützen).

War in Kiev (1018)

Bolesław organised his first expedition east, to support his son-in-lawSviatopolk I

Sviatopolk I Vladimirovich (''Sviatopolk the Accursed'', the ''Accursed Prince''; orv, Свѧтоплъкъ, translit=Svętoplŭkŭ; russian: Святополк Окаянный; uk, Святополк Окаянний; c. 980 – 1019) was the ...

of Kiev, in 1013, but the decisive engagements were to take place in 1018 after the Peace of Bautzen

The Peace of Bautzen (; ; ) was a treaty concluded on 30 January 1018, between Holy Roman Emperor Henry II and Bolesław I of Poland which ended a series of Polish-German wars over the control of Lusatia and Upper Lusatia (''Milzenerland'' or ...

was already signed.Tymieniecki Kazimierz, ''Bolesław Chrobry''. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): ''Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja.'' Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. . Page 252 At the request of Sviatopolk I, in what became known as the Kiev Expedition of 1018, the Polish duke sent an expedition to Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

with an army of 2,000–5,000 Polish warriors, in addition to Thietmar's reported 1,000 Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks tr, Peçenek(ler), Middle Turkic: , ro, Pecenegi, russian: Печенег(и), uk, Печеніг(и), hu, Besenyő(k), gr, Πατζινάκοι, Πετσενέγοι, Πατζινακίται, ka, პა� ...

, 300 German knights, and 500 Hungarian mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes Pseudonym, also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a memb ...

. After collecting his forces during June, Bolesław led his troops to the border in July and on 23 July at the banks of the Bug River

uk, Західний Буг be, Захо́дні Буг

, name_etymology =

, image = Wyszkow_Bug.jpg

, image_size = 250

, image_caption = Bug River in the vicinity of Wyszków, Poland

, map = Vi ...

, near Wołyń, he defeated the forces of Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav the Wise or Yaroslav I Vladimirovich; russian: Ярослав Мудрый, ; uk, Ярослав Мудрий; non, Jarizleifr Valdamarsson; la, Iaroslaus Sapiens () was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death. He was al ...

, Prince of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, in what became known as the Battle of the River Bug

The Battle of the River Bug, sometimes known as the Battle of Volhynia, was a battle that took place on 22–23 July 1018, in Red Ruthenia, near the Bug River and near Volhynia (Wołyń), between the forces of Bolesław I the Brave of Poland and Y ...

. All primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called an original source) is an artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was created at the time under ...

s agree that the Polish prince was victorious in battle. Yaroslav retreated north to Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

, opening the road to Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

. The city, which suffered from fires caused by the Pecheneg

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks tr, Peçenek(ler), Middle Turkic: , ro, Pecenegi, russian: Печенег(и), uk, Печеніг(и), hu, Besenyő(k), gr, Πατζινάκοι, Πετσενέγοι, Πατζινακίται, ka, პაჭ ...

siege, surrendered upon seeing the main Polish force on 14 August.''Wyprawa Kijowska Chrobrego'' Chwała Oręża Polskiego Nr 2. Rzeczpospolita and Mówią Wieki. Primary author Rafał Jaworski. 5 August 2006. P. 10 The entering army, led by Bolesław, was ceremonially welcomed by the local archbishop and the family of Vladimir I of Kiev

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

. According to popular legend Bolesław notched his sword (Szczerbiec

Szczerbiec () is the ceremonial sword used in the coronations of most Polish monarchs from 1320 to 1764. It now is displayed in the treasure vault of the royal Wawel Castle in Kraków, as the only preserved part of the medieval Polish crown jewe ...

) hitting the Golden Gate of Kiev.''Wyprawa Kijowska Chrobrego'' Chwała Oręża Polskiego Nr 2. ''Rzeczpospolita'' and Mówią Wieki. Primary author Rafał Jaworski. 5 August 2006. P. 11 Although Sviatopolk lost the throne soon afterwards and lost his life the following year, during this campaign Poland re-annexed the Red Strongholds, later called Red Ruthenia

Red Ruthenia or Red Rus' ( la, Ruthenia Rubra; '; uk, Червона Русь, Chervona Rus'; pl, Ruś Czerwona, Ruś Halicka; russian: Червонная Русь, Chervonnaya Rus'; ro, Rutenia Roșie), is a term used since the Middle Ages fo ...

, lost by Bolesław's father in 981.

Last years (1019–1025)

Historians dispute the exact date of Bolesław's

Historians dispute the exact date of Bolesław's coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

. The year 1025 is most widely accepted by scholars, though the year 1000 is also likely. According to an epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

, the crowning took place when Otto bestowed upon Bolesław royal regalia at the Congress of Gniezno

The Congress of Gniezno ( pl, Zjazd gnieźnieński, german: Akt von Gnesen or ''Gnesener Übereinkunft'') was an amicable meeting between the Polish Duke Bolesław I the Brave and Emperor Otto III, which took place at Gniezno in Poland on 11 Ma ...

. However, independent German sources confirmed that after Henry II's death in 1024, Bolesław took advantage of the interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

in Germany and crowned himself king in 1025. It is generally assumed that the coronation took place on Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel P ...

although Tadeusz Wojciechowski

Tadeusz Wojciechowski (b. 13 June 1838 in Kraków, d. 21 November 1919 in Lwów) was a Polish historian, professor, and rector of the University of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine; then in the Austro-Hungary). One of the founders of the Polish Historic ...

believes that the coronation took place prior to this, on 24 December 1024. The basis for this assertion is that the coronations of kings were usually held during religious festivities. The exact place of the coronation is also highly debated, with the cathedrals of Gniezno

Gniezno (; german: Gnesen; la, Gnesna) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. One of the Piast dynasty's chief cities, ...

or Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

being the most probable locations. Poland was thereafter raised to the rank of a kingdom before its neighbour, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

.

Wipo of Burgundy in his Chronicle describes this event:

It is widely believed that Bolesław had to receive permission for his coronation from the newly-elected Pope John XIX

Pope John XIX ( la, Ioannes XIX; died October 1032), born Romanus, was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 1024 to his death. He belonged to the family of the powerful counts of Tusculum, succeeding his brother, Benedict VIII ...

. John was known to be corrupt and it's likely that consent was or could have been obtained through bribes

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corru ...

. However, Rome also hoped for a potential alliance to defend itself from Byzantine Emperor Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

, who launched a military expedition to recover the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and who could subsequently threaten the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

from the south. Stanisław Zakrzewski put forward the theory that the coronation had the tacit consent of Conrad II

Conrad II ( – 4 June 1039), also known as and , was the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 1027 until his death in 1039. The first of a succession of four Salian emperors, who reigned for one century until 1125, Conrad ruled the kingdoms ...

and that the pope only confirmed this fact. This is corroborated by Conrad's confirmation of the royal title to Mieszko II, his agreement with the counts of Tusculum

The counts of Tusculum, also known as the Theophylacti, were a family of secular noblemen from Latium that maintained a powerful position in Rome between the 10th and 12th centuries. Several popes and an antipope during the 11th century came from ...

, and the papal interactions with Conrad and Bolesław.

Death and burial

According to

According to Cosmas of Prague

Cosmas of Prague ( cs, Kosmas Pražský; la, Cosmas Decanus; – October 21, 1125) was a priest, writer and historian.

Life

Between 1075 and 1081, he studied in Liège. After his return to Bohemia, he married Božetěcha, with whom he had a so ...

, Bolesław I died shortly after his coronation on 17 June 1025. Already in advanced age for the time, the true cause of death is unknown and remains a matter of speculation. Chronicler Jan Długosz

Jan Długosz (; 1 December 1415 – 19 May 1480), also known in Latin as Johannes Longinus, was a Polish priest, chronicler, diplomat, soldier, and secretary to Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki of Kraków. He is considered Poland's first histo ...

(and followed by modern historians and archaeologists) writes that Bolesław was laid to rest at the Archcathedral Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul in Poznań. In the 14th century, Casimir III the Great

Casimir III the Great ( pl, Kazimierz III Wielki; 30 April 1310 – 5 November 1370) reigned as the King of Poland from 1333 to 1370. He also later became King of Ruthenia in 1340, and fought to retain the title in the Galicia-Volhynia Wars. He ...

reportedly ordered the construction of a new, presumably Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

, sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

to which he transferred Bolesław's remains.

The medieval sarcophagus was partially damaged on 30 September 1772 during a fire, and completely destroyed in 1790 due to the collapse of the southern tower. Bolesław's remains were subsequently excavated from the rubble and moved to the cathedral's chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole commun ...

. Three bone fragments were donated to Tadeusz Czacki

Tadeusz Czacki (28 August 1765 in Poryck, Volhynia – 8 February 1813 in Dubno) was a Polish historian, pedagogue and numismatist. Czacki played an important part in the Enlightenment in Poland.

Biography

Czacki was born in Poryck in Volhynia ...

in 1801, at his request. Czacki, a notable Polish historian, pedagogue, and numismatist, placed one of the bone fragments in his ancestral mausoleum in Poryck (now Pavlivka) in the Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

region; the other two were given to Princess Izabela Flemming Czartoryska, who placed them in her recently founded Czartoryski Museum

The Princes Czartoryski Museum ( pl, Muzeum Książąt Czartoryskich ) – often abbreviated to Czartoryski Museum – is a historic museum in Kraków, Poland, and one of the country's oldest museums. The initial collection was formed in 1796 i ...

in Puławy

Puławy (, also written Pulawy) is a city in eastern Poland, in Lesser Poland's Lublin Voivodeship, at the confluence of the Vistula and Kurówka Rivers. Puławy is the capital of Puławy County. The city's 2019 population was estimated at 47,4 ...

.

After many historical twists, the burial place of Bolesław I ultimately remained at Poznań Cathedral, in the Golden Chapel. The content of his epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

is known to historians. It is Bolesław's epitaph, which, in part, came from the original tombstone, that is one of the first sources (dated to the period immediately after Bolesław's death, probably during the reign of Mieszko IIPrzemysław Wiszewski: ''Domus Bolezlai. W poszukiwaniu tradycji dynastycznej Piastów (do około 1138 roku)'', Wrocław 2008, p. 62.) that gave the King his widely known nickname of "Brave" (Polish: ''Chrobry''). Later, Gallus Anonymus

''Gallus Anonymus'' ( Polonized variant: ''Gall '') is the name traditionally given to the anonymous author of ''Gesta principum Polonorum'' (Deeds of the Princes of the Poles), composed in Latin between 1112 and 1118.

''Gallus'' is generally rega ...

, in Chapter 6 of his ''Gesta principum Polonorum

The ''Gesta principum Polonorum'' (; "''Deeds of the Princes of the Poles''") is the oldest known medieval chronicle documenting the history of Poland from the legendary times until 1113. Written in Latin by an anonymous author, it was most lik ...

'', named the Polish ruler as ''Bolezlavus qui dicebatur Gloriosus seu Chrabri''.

Family

The contemporaneous

The contemporaneous Thietmar of Merseburg

Thietmar (also Dietmar or Dithmar; 25 July 9751 December 1018), Prince-Bishop of Merseburg from 1009 until his death, was an important chronicler recording the reigns of German kings and Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (Saxon) dynasty. Two ...

recorded Bolesław's marriages, also mentioning his children. Bolesław's first wife was a daughter of Rikdag, Margrave of Meissen

This article lists the margraves of Meissen, a march and territorial state on the eastern border of the Holy Roman Empire.

History

King Henry the Fowler, on his 928-29 campaign against the Slavic Glomacze tribes, had a fortress erected on a ...

. Historian Manteuffel says that the marriage was arranged in the early 980s by Mieszko I who wanted to strengthen his links with the Saxon lords and to enable his son to succeed Rikdag in Meissen. Bolesław "later sent her away", according to Thietmar's ''Chronicon''. Historian Marek Kazimierz Barański writes that Bolesław repudiated his first wife after her father's death in 985 which left the marriage without any political value.

Bolesław "took a Hungarian woman" as his second wife. Most historians identify her as a daughter of the Hungarian ruler Géza, but this theory has not been universally accepted. She gave birth to a son, Bezprym

Bezprym ( hu, Veszprém; 986–1032) was the duke of Poland from 1031 until his death. He was the eldest son of King Bolesław the Brave, but was deprived of the succession by his father, who around 1001 sent him to Italy in order to become a mon ...

, but Bolesław repudiated her.

Bolesław's third wife, Emnilda, was "a daughter of the venerable lord, Dobromir". Her father was a West Slavic or Lechitic prince, either a local ruler from present-day Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

who was closely related to the imperial Liudolfing

The Ottonian dynasty (german: Ottonen) was a Saxon dynasty of German monarchs (919–1024), named after three of its kings and Holy Roman Emperors named Otto, especially its first Emperor Otto I. It is also known as the Saxon dynasty after th ...

dynasty, or the last independent prince of the Vistulans, before their incorporation into Poland. Wiszewski dates the marriage of Bolesław and Emnilda to 988. Emnilda exerted a beneficial influence on Bolesław, reforming "her husband's unstable character", according to Thietmar of Merseburg's report. Bolesław's and Emnilda's oldest (unnamed) daughter "was an abbess" of an unidentified abbey. Their second daughter Regelinda

Regelinda (german: Reg(e)lindis; - 21 March aft. 1014), a member of the Polish Piast dynasty, was Margravine of Meissen from 1009 until her death by her marriage with Margrave Herman I.

Life

She was the daughter of the Polish King Bolesław th ...

, who was born in 989, was given in marriage to Herman I, Margrave of Meissen

Herman I (german: Hermann; – 1 November 1038) was Margrave of Meissen from 1009 until his death.

Life

He was the eldest son of Margrave Eckard I of Meissen and his wife Swanehilde, a daughter of Margrave Hermann Billung. On 30 April 1002 his ...

in 1002 or 1003. Mieszko II Lambert

Mieszko II Lambert (; c. 990 – 10/11 May 1034) was King of Poland from 1025 to 1031, and Duke from 1032 until his death.

He was the second son of Bolesław I the Brave, but the eldest born from his third wife Emnilda of Lusatia. He was pro ...

who was born in 990 was Bolesław's favorite son and successor. The name of Bolesław's and Emnilda's third daughter, who was born in 995, is unknown; she married Sviatopolk I of Kiev

Sviatopolk I Vladimirovich (''Sviatopolk the Accursed'', the ''Accursed Prince''; orv, Свѧтоплъкъ, translit=Svętoplŭkŭ; russian: Святополк Окаянный; uk, Святополк Окаянний; c. 980 – 1019) was the ...

between 1005 and 1012. Bolesław's youngest son, Otto, was born in 1000.

Bolesław's fourth marriage, from 1018 until his death, was to Oda ( 995 – 1025), daughter of Margrave Eckard I of Meissen

Eckard I (''Ekkehard'';Rarely ''Ekkard'' or ''Eckhard''. Contemporary Latin variants to his name include ''Ekkihardus'', ''Eggihardus'', ''Eggihartus'', ''Heckihardus'', ''Egihhartus'', and ''Ekgihardus''. – 30 April 1002) was Margrave of Meiss ...

. They had a daughter, Matilda ( 1018 – 1036), betrothed (or married) on 18 May 1035 to Otto of Schweinfurt.

Marriages and Issue:

Oda/Hunilda?, daughter of Rikdag

Unknown Hungarian woman (sometimes identified as Judith of Hungary):

# Bezprym

Bezprym ( hu, Veszprém; 986–1032) was the duke of Poland from 1031 until his death. He was the eldest son of King Bolesław the Brave, but was deprived of the succession by his father, who around 1001 sent him to Italy in order to become a mon ...

(c. 986 – 1032) – became Duke of Poland

Emnilda, daughter of Dobromir:

# Unknown abbess of an unidentified abbey

# Regelinda (c. 989 – 21 March aft. 1014), married Herman I, Margrave of Meissen

Herman I (german: Hermann; – 1 November 1038) was Margrave of Meissen from 1009 until his death.

Life

He was the eldest son of Margrave Eckard I of Meissen and his wife Swanehilde, a daughter of Margrave Hermann Billung. On 30 April 1002 his ...

becoming Margravine of Meissen

# Mieszko II Lambert

Mieszko II Lambert (; c. 990 – 10/11 May 1034) was King of Poland from 1025 to 1031, and Duke from 1032 until his death.

He was the second son of Bolesław I the Brave, but the eldest born from his third wife Emnilda of Lusatia. He was pro ...

(c. 990 – 10/11 May 1034), became king and subsequently duke of Poland

# Unknown daughter, married Grand Prince Sviatopolk I of Kiev

Sviatopolk I Vladimirovich (''Sviatopolk the Accursed'', the ''Accursed Prince''; orv, Свѧтоплъкъ, translit=Svętoplŭkŭ; russian: Святополк Окаянный; uk, Святополк Окаянний; c. 980 – 1019) was the ...

and became Grand Princess of Kiev

# Otto Bolesławowic (c.1000 – 1033)

Oda of Meissen

Oda of Meissen, also named Ode, Old High German form for ''Uta'' or ''Ute'' ( pl, Oda Miśnieńska, german: Oda von Meißen; born c. 996 – died 31 October or 13 November after 1025), was a Saxon countess member of the Ekkehardiner dynasty. She ...