Black September on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Black September ( ar, أيلول الأسود; ''

After Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950, it conferred its citizenship on the West Bank Palestinians. The combined population of the West Bank and Jordan consisted of two-thirds Palestinians (one-third in the West Bank and one-third in the East Bank) and one-third Jordanians. Jordan provided Palestinians with seats amounting to half the parliament and Palestinians enjoyed equal opportunities in all sectors of the state. This demographic change influenced Jordanian politics.

After Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950, it conferred its citizenship on the West Bank Palestinians. The combined population of the West Bank and Jordan consisted of two-thirds Palestinians (one-third in the West Bank and one-third in the East Bank) and one-third Jordanians. Jordan provided Palestinians with seats amounting to half the parliament and Palestinians enjoyed equal opportunities in all sectors of the state. This demographic change influenced Jordanian politics.

Both sides declared victory: Israel had fulfilled its objective of destroying the Karameh camp, but failed to capture Arafat, while Jordan and the PLO had exacted relatively heavy Israeli casualties. Although the Palestinians had limited success in inflicting Israeli casualties, King Hussein let them take the credit. The fedayeen used the battle's wide acclaim and recognition in the Arab world to establish their national claims. The Karameh operation also highlighted the vulnerability of bases close to the Jordan River, so the PLO moved them farther into the mountains. Further Israeli attacks targeted Palestinian militants residing among the Jordanian civilian population, giving rise to friction between Jordanians and guerrillas.

Palestinians and Arabs generally considered the battle a psychological victory over the IDF, which had been seen as "invincible" until then, and recruitment into guerilla units soared. Fatah reported that 5,000 volunteers had applied to join within 48 hours of the events at Karameh. By late March, there were nearly 20,000 fedayeen in Jordan. Iraq and Syria offered training programs for several thousand guerrillas. The

Both sides declared victory: Israel had fulfilled its objective of destroying the Karameh camp, but failed to capture Arafat, while Jordan and the PLO had exacted relatively heavy Israeli casualties. Although the Palestinians had limited success in inflicting Israeli casualties, King Hussein let them take the credit. The fedayeen used the battle's wide acclaim and recognition in the Arab world to establish their national claims. The Karameh operation also highlighted the vulnerability of bases close to the Jordan River, so the PLO moved them farther into the mountains. Further Israeli attacks targeted Palestinian militants residing among the Jordanian civilian population, giving rise to friction between Jordanians and guerrillas.

Palestinians and Arabs generally considered the battle a psychological victory over the IDF, which had been seen as "invincible" until then, and recruitment into guerilla units soared. Fatah reported that 5,000 volunteers had applied to join within 48 hours of the events at Karameh. By late March, there were nearly 20,000 fedayeen in Jordan. Iraq and Syria offered training programs for several thousand guerrillas. The

The PLO would not live up to the agreement, and came to be seen more and more as a state within a state in Jordan. Fatah's Yasser Arafat replaced

The PLO would not live up to the agreement, and came to be seen more and more as a state within a state in Jordan. Fatah's Yasser Arafat replaced  According to Shlaim, their growing power was accompanied by growing arrogance and insolence. He quotes an observer describing the PLO in Jordan,

:

Palestinians claimed there were numerous

According to Shlaim, their growing power was accompanied by growing arrogance and insolence. He quotes an observer describing the PLO in Jordan,

:

Palestinians claimed there were numerous

Libya, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, who were openly supporting the fedayeen, sent Jordan financial subsidies, placing Hussein in a difficult position. Hussein saw no external forces to support him other than the United States and Israel, but that would act as fuel for fedayeen propaganda against him. On 17 February 1970, the American embassy in Tel Aviv relayed three questions from Hussein to Israel asking about Israel's stance if Jordan chose to confront the fedayeen. Israel replied positively to Hussein, and committed that they would not take advantage if Jordan withdrew its troops from the borders for a potential confrontation.

Israeli artillery and airforce attacked Irbid on 3 June as reprisal for a fedayeen attack on

Libya, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, who were openly supporting the fedayeen, sent Jordan financial subsidies, placing Hussein in a difficult position. Hussein saw no external forces to support him other than the United States and Israel, but that would act as fuel for fedayeen propaganda against him. On 17 February 1970, the American embassy in Tel Aviv relayed three questions from Hussein to Israel asking about Israel's stance if Jordan chose to confront the fedayeen. Israel replied positively to Hussein, and committed that they would not take advantage if Jordan withdrew its troops from the borders for a potential confrontation.

Israeli artillery and airforce attacked Irbid on 3 June as reprisal for a fedayeen attack on

Hussein's motorcade came under fire on 1 September for the second time in three months, triggering clashes between the army and the fedayeen in Amman up until 6 September. On 6 September, three planes were hijacked by the PFLP:

Hussein's motorcade came under fire on 1 September for the second time in three months, triggering clashes between the army and the fedayeen in Amman up until 6 September. On 6 September, three planes were hijacked by the PFLP:  Al-Jazy, the perceived pro-Palestinian newly appointed army chief of staff, resigned on 9 September in the midst of the hijacking crisis, and was replaced by

Al-Jazy, the perceived pro-Palestinian newly appointed army chief of staff, resigned on 9 September in the midst of the hijacking crisis, and was replaced by

On the evening of 15 September, Hussein called in his advisors for an emergency meeting at his Al-Hummar residence on the western outskirts of Amman.

On the evening of 15 September, Hussein called in his advisors for an emergency meeting at his Al-Hummar residence on the western outskirts of Amman.

There were also concerns of Iraqi interference. A 17,000-man 3rd Armoured Division of the Iraqi Army had remained in eastern Jordan since after the 1967 Six-Day War. The Iraqi government sympathized with the Palestinians, but it was unclear whether the division would get involved in the conflict in favor of the fedayeen. Thus, the Jordanian 99th Brigade had to be detailed to monitor the Iraqis.

David Raab, one of the plane hijacking hostages, described the initial military actions of Black September:

Hussein arranged a cabinet meeting on the evening of the Syrian incursion, leaving them to decide if Jordan should seek foreign intervention. Two sides emerged from the meeting; one group of ministers favored military intervention from the United Kingdom or the United States, while the other group argued that it was an Arab affair that ought to be dealt with internally. The former group prevailed as Jordan was facing an existential threat. Britain refused to interfere militarily for fear of getting involved in a region-wide conflict; arguments such as "Jordan as it is is not a viable country" emerged. The British cabinet then decided to relay the Hussein's request to the Americans. Nixon and Kissinger were receptive to Hussein's request. Nixon ordered the

There were also concerns of Iraqi interference. A 17,000-man 3rd Armoured Division of the Iraqi Army had remained in eastern Jordan since after the 1967 Six-Day War. The Iraqi government sympathized with the Palestinians, but it was unclear whether the division would get involved in the conflict in favor of the fedayeen. Thus, the Jordanian 99th Brigade had to be detailed to monitor the Iraqis.

David Raab, one of the plane hijacking hostages, described the initial military actions of Black September:

Hussein arranged a cabinet meeting on the evening of the Syrian incursion, leaving them to decide if Jordan should seek foreign intervention. Two sides emerged from the meeting; one group of ministers favored military intervention from the United Kingdom or the United States, while the other group argued that it was an Arab affair that ought to be dealt with internally. The former group prevailed as Jordan was facing an existential threat. Britain refused to interfere militarily for fear of getting involved in a region-wide conflict; arguments such as "Jordan as it is is not a viable country" emerged. The British cabinet then decided to relay the Hussein's request to the Americans. Nixon and Kissinger were receptive to Hussein's request. Nixon ordered the  On 22 September, Hussein ordered the Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF) to attack the Syrian forces. A joint air-ground offensive proved successful, contributing to the success was the

On 22 September, Hussein ordered the Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF) to attack the Syrian forces. A joint air-ground offensive proved successful, contributing to the success was the

The Jordanian army regained control of key cities and intersections in the country before accepting the ceasefire agreement brokered by Egypt's Nasser. Hussein appointed a Palestinian, Ahmad Toukan, as prime minister, instructing him to "bandage the wounds". In the period following the ceasefire, Hussein publicly revealed that the Jordanian army had uncovered around 360 underground PLO bases in Amman, and that Jordan held 20,000 detainees, among whom were "Chinese advisors".

The Jordanian army regained control of key cities and intersections in the country before accepting the ceasefire agreement brokered by Egypt's Nasser. Hussein appointed a Palestinian, Ahmad Toukan, as prime minister, instructing him to "bandage the wounds". In the period following the ceasefire, Hussein publicly revealed that the Jordanian army had uncovered around 360 underground PLO bases in Amman, and that Jordan held 20,000 detainees, among whom were "Chinese advisors".

Another agreement, called the Amman agreement, was signed between Hussein and Arafat on 13 October. It mandated that the fedayeen respect Jordanian sovereignty and desist from wearing uniforms or bearing arms in public. However it contained a clause requiring that Jordan recognize the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinians; Wasfi Tal rejected this clause. Habash and Hawatmeh continued their attacks on the monarchy in spite of the Amman agreement. Hussein appointed Tal to form a government. Tal was seen as anti-Palestinian, however he had made pro-Palestinian gestures during his previous two tenures as prime minister. Tal viewed Arafat with suspicion as he considered that the PLO concentrated its efforts against the Jordanian state rather than against Israel. On one occasion, Tal lost his temper and shouted at Arafat "You are a liar; you don't want to fight Israel!". Shlaim describes Tal as a more uncompromising figure than Hussein, and very popular with the army.

Clashes between the army, and the PFLP and DFLP, ensued after Tal was instated. Tal launched an offensive against fedayeen bases along the Amman-Jerash road in January 1971, and the army drove them out of Irbid in March. In April, Tal ordered the PLO to relocate all its bases from Amman to the forests between Ajloun and Jerash. The fedayeen initially resisted, but they were hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. In July, the army surrounded the last remaining 2,000 fedayeen from the Ajloun-Jerash area. The fedayeen finally surrendered and were allowed to leave to Syria, some 200 fighters preferred to cross the

Another agreement, called the Amman agreement, was signed between Hussein and Arafat on 13 October. It mandated that the fedayeen respect Jordanian sovereignty and desist from wearing uniforms or bearing arms in public. However it contained a clause requiring that Jordan recognize the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinians; Wasfi Tal rejected this clause. Habash and Hawatmeh continued their attacks on the monarchy in spite of the Amman agreement. Hussein appointed Tal to form a government. Tal was seen as anti-Palestinian, however he had made pro-Palestinian gestures during his previous two tenures as prime minister. Tal viewed Arafat with suspicion as he considered that the PLO concentrated its efforts against the Jordanian state rather than against Israel. On one occasion, Tal lost his temper and shouted at Arafat "You are a liar; you don't want to fight Israel!". Shlaim describes Tal as a more uncompromising figure than Hussein, and very popular with the army.

Clashes between the army, and the PFLP and DFLP, ensued after Tal was instated. Tal launched an offensive against fedayeen bases along the Amman-Jerash road in January 1971, and the army drove them out of Irbid in March. In April, Tal ordered the PLO to relocate all its bases from Amman to the forests between Ajloun and Jerash. The fedayeen initially resisted, but they were hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. In July, the army surrounded the last remaining 2,000 fedayeen from the Ajloun-Jerash area. The fedayeen finally surrendered and were allowed to leave to Syria, some 200 fighters preferred to cross the

The Black September Organization was established by Fatah members in 1971 for reprisal operations and international strikes after the September events. On 28 November 1971, four of the group's members assassinated Prime Minister

The Black September Organization was established by Fatah members in 1971 for reprisal operations and international strikes after the September events. On 28 November 1971, four of the group's members assassinated Prime Minister

Footage of events of Black September

1976 documentary about the fedayeen

{{Middle East conflicts 1970 in international relations 1970 in Jordan 1971 in international relations 1971 in Jordan Articles containing video clips Civil wars post-1945 Cold War conflicts Conflicts in 1970 Conflicts in 1971 Conflicts involving the People's Mujahedin of Iran Foreign relations of the Soviet Union Jordan–State of Palestine relations Jordan–Syria relations Pakistan military presence in other countries Palestine Liberation Organization Wars involving Jordan Wars involving Palestinians Wars involving Syria

Aylūl

The Arabic names of the months of the Gregorian calendar are usually phonetic Arabic pronunciations of the corresponding month names used in European languages. An exception is the Syriac calendar used in Iraq and the Levant, whose month name ...

Al-Aswad''), also known as the Jordanian Civil War, was a conflict fought in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Riv ...

between the Jordanian Armed Forces

The Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) ( ar, الْقُوَّاتُ الْمُسَلَّحَةُ الأرْدُنِية, romanized: ''Al-Quwwat Al-Musallaha Al-Urduniyya''), also referred to as the Arab Army ( ar, الْجَيْشُ الْعَرَب� ...

(JAF), under the leadership of King Hussein

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family o ...

, and the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

(PLO), under the leadership of Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

, primarily between 16 and 27 September 1970, with certain aspects of the conflict continuing until 17 July 1971.

After Jordan lost control

Control may refer to:

Basic meanings Economics and business

* Control (management), an element of management

* Control, an element of management accounting

* Comptroller (or controller), a senior financial officer in an organization

* Controllin ...

of the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

to Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in 1967, Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

fighters known as fedayeen moved their bases to Jordan and stepped up their attacks on Israel and Israeli-occupied territories

Israeli-occupied territories are the lands that were captured and occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967. While the term is currently applied to the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights, it has also been used to refer to a ...

. One Israeli retaliation on a PLO camp based in Karameh

Al-Karameh ( ar, الكرامة), or simply Karameh, is a town in west-central Jordan, near the Allenby Bridge which spans the Jordan River. Karameh sits on the eastern bank of the river, along the border between Jordan, Israel, as well as the Isr ...

, a Jordanian town along the border with the West Bank, developed into a full-scale battle. The perceived joint Jordanian-Palestinian victory against Israel during the 1968 Battle of Karameh

The Battle of Karameh ( ar, معركة الكرامة) was a 15-hour military engagement between the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and combined forces of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) in the Jor ...

led to an upsurge in Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

support for the fedayeen in Jordan, in both new recruits and financial aid. The PLO's strength in Jordan grew, and by the beginning of 1970, groups within the PLO had begun openly calling for the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

.

Acting as a state within a state, the fedayeen disregarded local laws and regulations, and even attempted to assassinate King Hussein twice—leading to violent confrontations between them and the Jordanian Army

The Royal Jordanian Army (Arabic: القوّات البرية الاردنيّة; ) is the Army, ground force branch of the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF). It draws its origins from units such as the Arab Legion, formed in the Emirate of Transjord ...

in June 1970. Hussein wanted to oust them from the country, but hesitated to strike because he did not want his enemies to use it against him by equating Palestinian fighters with civilians. PLO actions in Jordan culminated in the Dawson's Field hijackings

In September 1970, members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked four airliners bound for New York City and one for London. Three aircraft were forced to land at Dawson's Field, a remote desert airstrip near Zarqa ...

incident of 6 September, in which the PFLP

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine ( ar, الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, translit=al-Jabhah al-Sha`biyyah li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, PFLP) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary so ...

hijacked three civilian aircraft and forced their landing in Zarqa

Zarqa ( ar, الزرقاء) is the capital of Zarqa Governorate in Jordan. Its name means "the blue (city)". It had a population of 635,160 inhabitants in 2015, and is the most populous city in Jordan after Amman.

Geography

Zarqa is located in t ...

, taking foreign nationals as hostages, and later blowing up the planes in front of international press. Hussein saw this as the last straw, and ordered the army to take action.

On 17 September, the Jordanian Army surrounded cities with significant PLO presence including Amman

Amman (; ar, عَمَّان, ' ; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''Rabat ʻAmān'') is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of 4,061,150 a ...

and Irbid, and began shelling Palestinian refugee camps where the fedayeen were established. The next day, forces from the Syrian Army

" (''Guardians of the Homeland'')

, colors = * Service uniform: Khaki, Olive

* Combat uniform: Green, Black, Khaki

, anniversaries = August 1st

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

, battles = 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Six ...

, with Palestine Liberation Army

The Palestine Liberation Army (PLA, ar, جيش التحرير الفلسطيني, ''Jaysh at-Tahrir al-Filastini'') is ostensibly the military wing of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), set up at the 1964 Arab League summit held in A ...

markings, intervened in support of the fedayeen and advanced towards Irbid which the fedayeen had occupied and declared to be a "liberated" city. On 22 September, the Syrians withdrew from Irbid after the Jordanians launched an air-ground offensive that inflicted heavy losses on the Syrians. Mounting pressure by Arab countries (such as Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

) led Hussein to halt the fighting. On 13 October he signed an agreement with Arafat to regulate the fedayeen's presence in Jordan. However, the Jordanian military attacked again in January 1971 and the fedayeen were driven out of the cities, one by one, until 2,000 fedayeen surrendered after being surrounded in a forest near Ajloun on 17 July, marking the end of the conflict.

Jordan allowed the fedayeen to leave for Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

via Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and the fedayeen later participated in the 1975 Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ar, الحرب الأهلية اللبنانية, translit=Al-Ḥarb al-Ahliyyah al-Libnāniyyah) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 120,000 fatalities a ...

. The Black September Organization

The Black September Organization (BSO) ( ar, منظمة أيلول الأسود, translit=Munaẓẓamat Aylūl al-Aswad) was a Palestinian militant organization founded in 1970. Besides other actions, the group was responsible for the assass ...

was founded after the conflict to carry out reprisals against Jordanian authorities, and the organization's first noted attack was the assassination of Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi Tal

Wasfi Tal ( ar, وصفي التل; also known as Wasfi Tell; 19 January 1919 – 28 November 1971) was a Jordanian politician, statesman and general. He served as the 15th Prime Minister of Jordan for three separate terms, 1962–63, 1965–67 a ...

in 1971 who had commanded parts of the operations that expelled the fedayeen. The organization then shifted to attacking Israeli targets, including the highly publicized Munich massacre

The Munich massacre was a terrorist attack carried out during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, West Germany, by eight members of the Palestinian militant organization Black September, who infiltrated the Olympic Village, killed two member ...

of Israeli athletes. Even though Black September did not reflect a Jordanian-Palestinian divide, as there were Palestinians and Jordanians on both sides of the conflict, it paved the way for such a divide subsequently.

Background

Palestinians in Jordan

After Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950, it conferred its citizenship on the West Bank Palestinians. The combined population of the West Bank and Jordan consisted of two-thirds Palestinians (one-third in the West Bank and one-third in the East Bank) and one-third Jordanians. Jordan provided Palestinians with seats amounting to half the parliament and Palestinians enjoyed equal opportunities in all sectors of the state. This demographic change influenced Jordanian politics.

After Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950, it conferred its citizenship on the West Bank Palestinians. The combined population of the West Bank and Jordan consisted of two-thirds Palestinians (one-third in the West Bank and one-third in the East Bank) and one-third Jordanians. Jordan provided Palestinians with seats amounting to half the parliament and Palestinians enjoyed equal opportunities in all sectors of the state. This demographic change influenced Jordanian politics.

King Hussein

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family o ...

considered that the Palestinian problem would remain the country's overriding national security issue; he feared an independent West Bank under PLO administration would threaten the autonomy of his Hashemite kingdom. The Palestinian factions were supported variously by many Arab governments, most notably Egypt's President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

, who gave them political support.

The Palestinian nationalist organization Fatah

Fatah ( ar, فتح '), formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist social democratic political party and the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and ...

started organizing cross-border attacks against Israel in January 1965, often drawing severe Israeli reprisals upon Jordan. The Samu Incident launched by Israel on 13 November 1966 was one such reprisal, after three Israeli soldiers were killed by a Fatah landmine. The Israeli assault on the Jordanian controlled West Bank town of As-Samu

As Samu' or es-Samu' ( ar, السموع) () is a town in the Hebron Governorate of the West Bank, Palestine, 12 kilometers south of the city of Hebron and 60 kilometers southwest of Jerusalem.

Geography

The area is a hilly, rocky area cut by ...

inflicted heavy casualties on Jordan. Israeli writer Avi Shlaim

Avraham "Avi" Shlaim (born 31 October 1945) is an Israeli-British historian, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Oxford and fellow of the British Academy. He is one of Israel's New Historians, a group of Israeli ...

argued that Israel's disproportionate retaliation exacted revenge on the wrong party, as Israeli leaders knew from their interaction with Hussein that he was doing everything he could to prevent such attacks. Hussein, who felt he had been betrayed by the Israelis, drew fierce local criticism because of this incident. It is thought that this contributed to his decision to join Egypt and Syria's war against Israel in 1967. In June 1967 Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan during the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

.

PLO's growing strength after the Battle of Karameh

After Jordan lost the West Bank, Fatah under the PLO stepped up their guerrilla attacks against Israel from Jordanian soil, making the border town of Karameh their headquarters. On 18 March 1968, an Israeli school bus was blown up by a mine near Be'er Ora in the Arava, killing two adults and wounding ten children—the 38th Fatah operation in little more than three months. On 21 March,Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

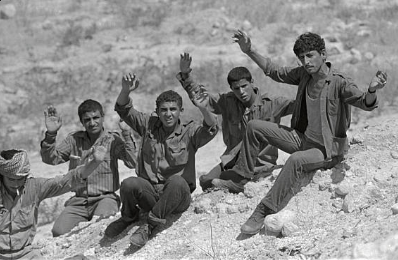

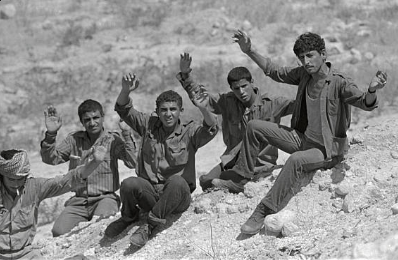

(IDF) units entered Jordan and launched a reprisal attack on Karameh that developed into a full-scale battle that lasted a day. The PLO suffered some 200 casualties and another 150 taken prisoner; 40–84 Jordanian soldiers were also killed. Israeli losses stood at around 30 killed and 69–161 wounded, and they also left behind several vehicles.

Both sides declared victory: Israel had fulfilled its objective of destroying the Karameh camp, but failed to capture Arafat, while Jordan and the PLO had exacted relatively heavy Israeli casualties. Although the Palestinians had limited success in inflicting Israeli casualties, King Hussein let them take the credit. The fedayeen used the battle's wide acclaim and recognition in the Arab world to establish their national claims. The Karameh operation also highlighted the vulnerability of bases close to the Jordan River, so the PLO moved them farther into the mountains. Further Israeli attacks targeted Palestinian militants residing among the Jordanian civilian population, giving rise to friction between Jordanians and guerrillas.

Palestinians and Arabs generally considered the battle a psychological victory over the IDF, which had been seen as "invincible" until then, and recruitment into guerilla units soared. Fatah reported that 5,000 volunteers had applied to join within 48 hours of the events at Karameh. By late March, there were nearly 20,000 fedayeen in Jordan. Iraq and Syria offered training programs for several thousand guerrillas. The

Both sides declared victory: Israel had fulfilled its objective of destroying the Karameh camp, but failed to capture Arafat, while Jordan and the PLO had exacted relatively heavy Israeli casualties. Although the Palestinians had limited success in inflicting Israeli casualties, King Hussein let them take the credit. The fedayeen used the battle's wide acclaim and recognition in the Arab world to establish their national claims. The Karameh operation also highlighted the vulnerability of bases close to the Jordan River, so the PLO moved them farther into the mountains. Further Israeli attacks targeted Palestinian militants residing among the Jordanian civilian population, giving rise to friction between Jordanians and guerrillas.

Palestinians and Arabs generally considered the battle a psychological victory over the IDF, which had been seen as "invincible" until then, and recruitment into guerilla units soared. Fatah reported that 5,000 volunteers had applied to join within 48 hours of the events at Karameh. By late March, there were nearly 20,000 fedayeen in Jordan. Iraq and Syria offered training programs for several thousand guerrillas. The Persian Gulf states

The Arab states of the Persian Gulf refers to a group of Arab states which border the Persian Gulf. There are seven member states of the Arab League in the region: Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. ...

, led by Kuwait, raised money for them through a 5% tax on the salaries of their tens of thousands of resident Palestinian workers, and a fund drive in Lebanon raised $500,000 from Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

alone. The Palestinian organizations also began to guarantee a lifetime support for the families of all guerrillas killed in action. Within a year after the battle, Fatah had branches in about eighty countries. After the battle, Fatah gained control of the PLO in Egypt.

Palestinian fedayeen from Syria and Lebanon started to converge on Jordan, mostly in Amman. In Palestinian enclaves and refugee camps in Jordan, the police and army were losing their authority. The Wehdat and Al-Hussein refugee camps came to be referred as "independent republics" and the fedayeen established administrative autonomy by establishing local government under the control of uniformed PLO militants—setting up checkpoints and attempting to extort "taxes" from civilians.

Seven-point agreement

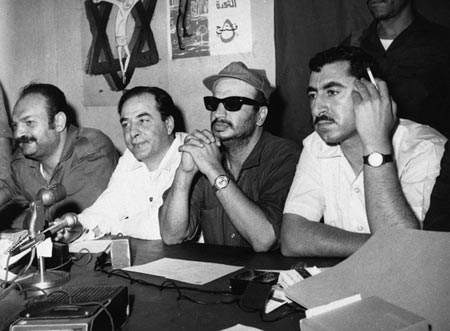

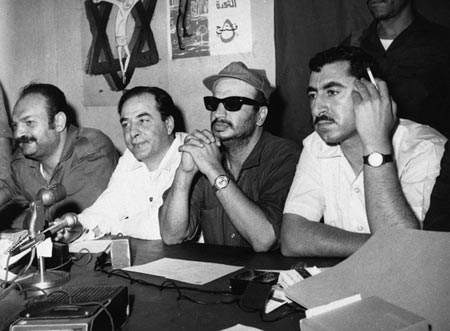

In early November 1968, the Jordanian army attacked a fedayeen group named "Al-Nasr" (meaning victory) after the group had attacked Jordanian police. Not all Palestinians were supportive of Al-Nasr's actions, but the Jordanian response was meant to send a message that there would be consequences for challenging the government's authority. Immediately after the incident, a seven-point agreement was reached between King Hussein and Palestinian organizations, that restrained unlawful and illegal fedayeen behavior against the Jordanian government. The PLO would not live up to the agreement, and came to be seen more and more as a state within a state in Jordan. Fatah's Yasser Arafat replaced

The PLO would not live up to the agreement, and came to be seen more and more as a state within a state in Jordan. Fatah's Yasser Arafat replaced Ahmad Shukeiri

Ahmad al-Shukeiri ( ar, أحمد الشقيري, also transliterated al-Shuqayri, Shuqairi, Shuqeiri, Shukeiry; 1 January 1908 – 26 February 1980) was the first Chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, serving from 1964–1967. ...

as the PLO's leader in February 1969. Discipline in the different Palestinian groups was poor, and the PLO had no central power to control the different groups. A situation developed of fedayeen groups rapidly spawning, merging, and splintering, sometimes trying to behave radically in order to attract recruits. Hussein went to the United States in March 1969 for talks with Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, the new American president. He argued for Israel's adherence to United Nations Security Council Resolution 242

United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 (S/RES/242) was adopted unanimously by the UN Security Council on November 22, 1967, in the aftermath of the Six-Day War. It was adopted under Chapter VI of the UN Charter. The resolution was spons ...

, in which it was required to return territories it had occupied in 1967 in return for peace. Palestinian factions were suspicious of Hussein, as this meant the withdrawal of his policy of forceful resistance towards Israel, and these suspicions were further heightened by Washington's claim that Hussein would be able to liquidate the fedayeen movement in his country upon resolution of the conflict.

Fatah favored not intervening in the internal affairs of other Arab countries. However, although it assumed the leadership of the PLO, more radical left-wing Palestinian movements refused to abide by that policy. By 1970, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine ( ar, الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, translit=al-Jabhah al-Sha`biyyah li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, PFLP) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary so ...

(PFLP) led by George Habash and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP; ar, الجبهة الديموقراطية لتحرير فلسطين, ''al-Jabha al-Dīmūqrāṭiyya li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn'') is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist organi ...

(DFLP) led by Nayef Hawatmeh, began to openly question the legitimacy of the Hashemite monarchy, and called for its overthrow and replacement with a revolutionary regime. Other radical groups included the Syrian Ba'ath's As-Sa'iqa

As-Sa'iqa ( ar, صاعقة, lit=Thunderbolt, translit=Saiqa) officially known as Vanguard for the Popular Liberation War - Lightning Forces, ( ar, طلائع حرب التحرير الشعبية - قوات الصاعقة ) is a Palestinian Ba' ...

, and the Iraqi Ba'ath's Arab Liberation Front

Arab Liberation Front ( ar, جبهة التحرير العربية ''Jabhet Al-Tahrir Al-'Arabiyah'') is a minor Palestinian political party, previously controlled by the Iraqi-led Ba'ath Party, formed in 1969 by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and then hea ...

: these saw Hussein as "a puppet of Western imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

", " a reactionary", and "a Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

tool". They claimed that the road to Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

passed through Amman, which they sought to transform into the Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi is ...

of Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

. They also stirred up conservative and religious feelings with provocative anti-religious statements and actions, such as putting up Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

and Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishme ...

slogans on mosque walls.

According to Shlaim, their growing power was accompanied by growing arrogance and insolence. He quotes an observer describing the PLO in Jordan,

:

Palestinians claimed there were numerous

According to Shlaim, their growing power was accompanied by growing arrogance and insolence. He quotes an observer describing the PLO in Jordan,

:

Palestinians claimed there were numerous agents provocateurs

An agent provocateur () is a person who commits, or who acts to entice another person to commit, an illegal or rash act or falsely implicate them in partaking in an illegal act, so as to ruin the reputation of, or entice legal action against, the ...

from Jordanian or other security services present among the fedayeen, deliberately trying to upset political relations and provide justification for a crackdown. There were frequent kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

s and acts of violence against civilians: Chief of the Jordanian Royal Court

A royal court, often called simply a court when the royal context is clear, is an extended royal household in a monarchy, including all those who regularly attend on a monarch, or another central figure. Hence, the word "court" may also be appl ...

(and subsequently Prime Minister) Zaid al-Rifai

Zaid al-Rifai ( ar, زيد الرفاعي) (born 27 November 1936 in Amman, Jordan) is a Jordanian politician that served as the 22nd Prime Minister of Jordan from April 1984 to April 1989.

Biography

He served as Prime Minister of Jordan and ...

claimed that in one extreme instance "the fedayeen killed a soldier, beheaded him, and played football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

with his head in the area where he used to live".''Arafat's War'' by Efraim Karsh

Efraim Karsh ( he, אפרים קארש; born 1953) is an Israeli–British historian who is the founding director and emeritus professor of Middle East and Mediterranean Studies at King's College London. Since 2013, he has served as professor of p ...

, p. 28

Ten-point edict and June confrontations

The situation placed Hussein in a severe dilemma: if he used force to oust the fedayeen, he would alienate himself from the Palestinians in the country and the Arab World. However, if he refused to act to strike back at the fedayeen, he would lose the respect of Jordanians, and more seriously, that of the army, the backbone of the regime, which already started to pressure Hussein to act against them. In February 1970, King Hussein visited Egyptian President Nasser in Cairo, and won his support for taking a tougher stance against the fedayeen. Nasser also agreed to influence the fedayeen to desist from undermining Hussein's regime. Upon his return, he published a ten-point edict restricting activities of the Palestinian organizations, which included prohibition of the following: carrying arms publicly, storing ammunitions in villages, and holding demonstrations and meetings without prior governmental consent. The fedayeen reacted violently to these efforts aimed at curbing their power, which led Hussein to freeze the new regulation; he also acquiesced to fedayeen demands of dismissing the perceived anti-Palestinian interior minister Muhammad Al-Kailani. Hussein's policy of giving concessions to the fedayeen was to gain time, but Western newspapers started floating sensationalized stories that Hussein was losing control over Jordan and that he might abdicate soon. Libya, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, who were openly supporting the fedayeen, sent Jordan financial subsidies, placing Hussein in a difficult position. Hussein saw no external forces to support him other than the United States and Israel, but that would act as fuel for fedayeen propaganda against him. On 17 February 1970, the American embassy in Tel Aviv relayed three questions from Hussein to Israel asking about Israel's stance if Jordan chose to confront the fedayeen. Israel replied positively to Hussein, and committed that they would not take advantage if Jordan withdrew its troops from the borders for a potential confrontation.

Israeli artillery and airforce attacked Irbid on 3 June as reprisal for a fedayeen attack on

Libya, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, who were openly supporting the fedayeen, sent Jordan financial subsidies, placing Hussein in a difficult position. Hussein saw no external forces to support him other than the United States and Israel, but that would act as fuel for fedayeen propaganda against him. On 17 February 1970, the American embassy in Tel Aviv relayed three questions from Hussein to Israel asking about Israel's stance if Jordan chose to confront the fedayeen. Israel replied positively to Hussein, and committed that they would not take advantage if Jordan withdrew its troops from the borders for a potential confrontation.

Israeli artillery and airforce attacked Irbid on 3 June as reprisal for a fedayeen attack on Beit Shean

Beit She'an ( he, בֵּית שְׁאָן '), also Beth-shean, formerly Beisan ( ar, بيسان ), is a town in the Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is be ...

, killing one soldier, as well as killing seven and injuring twenty-six civilians. The Jordanian army retaliated and shelled Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Fo ...

for the first time in 22 years; Hussein ordered the shelling but realized it was the start of a dangerous cycle of violence. Consequently, he requested, through the American embassy in Amman, a ceasefire with the Israelis to buy time so that he could take strong measures against the fedayeen. The message to Israel stated that "the Jordanian government was doing everything it could to prevent fedayeen rocket attacks on Israel. King deeply regrets the rocket attacks. Jordan Army under orders to shoot to kill any fedayeen attempting to fire rockets and fedayeen leaders had been told again evening of 3 June that violators would be shot on sight". Israel accepted Hussein's request following pressure from the Americans.

In the summer of 1970, the Jordanian army was on the verge of losing its patience with the fedayeen. After a provocation from the fedayeen, a tank battalion moved from the Jordan Valley

The Jordan Valley ( ar, غور الأردن, ''Ghor al-Urdun''; he, עֵמֶק הַיַרְדֵּן, ''Emek HaYarden'') forms part of the larger Jordan Rift Valley. Unlike most other river valleys, the term "Jordan Valley" often applies just to ...

without orders from Amman, intending to retaliate against them. It took the personal intervention of the King and that of the 3rd Armored Division commander Sharif

Sharīf ( ar, شريف, 'noble', 'highborn'), also spelled shareef or sherif, feminine sharīfa (), plural ashrāf (), shurafāʾ (), or (in the Maghreb) shurfāʾ, is a title used to designate a person descended, or claiming to be descended, fr ...

Shaker, who blocked the road with their cars, to stop its onslaught.

Fighting broke out again between the fedayeen and the army in Zarqa on 7 June. Two days later, the fedayeen opened fire on the General Intelligence Directorate's (''mukhabarat'') headquarters. Hussein went to visit the ''mukhabarat'' headquarters after the incident, but his motorcade came under heavy fedayeen fire, killing one of his guards. Bedouin units of the army retaliated for the assassination attempt against their king by shelling Al-Wehdat and Al-Hussein camps, which escalated into a conflict that lasted three days. An Israeli army meeting deliberated on events in Jordan; according to the director of Israel's Military Intelligence, there were around 2,000 fedayeen in Amman armed with mortars and Katyusha rockets

The Katyusha ( rus, Катю́ша, p=kɐˈtʲuʂə, a=Ru-Катюша.ogg) is a type of rocket artillery first built and fielded by the Soviet Union in World War II. Multiple rocket launchers such as these deliver explosives to a target area ...

. Hussein's advisors were divided: some were urging him to finish the job, while others were calling for restraint as victory could only be accomplished at the cost of thousands of lives, which to them was unacceptable. Hussein halted the fighting, and the three-day conflict's toll was around 300 dead and 700 wounded, including civilians.

A ceasefire was announced by Hussein and Arafat, but the PFLP did not abide by it. It immediately held around 68 foreign nationals hostage in two Amman hotels, threatening to blow them up with the buildings if Sharif Shaker and Sharif Nasser were not dismissed and the Special Forces

Special forces and special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equip ...

unit disbanded. Arafat did not agree with the PFLP, but had to play along as he feared public opinion. Hussein compromised and reduced tensions by appointing Mashour Haditha Al-Jazy

Mashour Haditha al-Jazy (1928-2001) was a Jordanian Lieutenant General, mostly known for participating in the Six-Day War and the Battle of Karameh

The Battle of Karameh ( ar, معركة الكرامة) was a 15-hour military engagement betw ...

, who was considered a moderate general, as army chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

, and Abdelmunim Al-Rifai

Abdul-Monem Rifai (ʻAbd al-Munʻim Rifāʻī) (23 February 1917 – 17 October 1985) was a Jordanian diplomat and political figure of Palestinian descent, who served two non-consecutive terms as the 18th Prime Minister of Jordan in 1969 and 19 ...

as prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, who in turn included six Palestinians as ministers in his government. Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, President Nixon's security advisor, gave the following assessment of the events in Jordan:

June 1970 became one of the most uncertain periods for the Hashemite monarchy in Jordan, as most foreign diplomats believed that events favored the fedayeen, and that the downfall of the monarchy was just a matter of time. Although Hussein was confident, members of his family started to wonder for how long the situation would last. 72-year-old Prince Zeid bin Hussein

Zaid bin Hussein, GCVO, GBE ( ar, زيد بن الحسين; February 28, 1898 – October 18, 1970) was an Iraqi prince who was a member of the Hashemite dynasty and the head of the Royal House of Iraq from 1958 until his death, after the roya ...

– the only son of Hussein bin Ali (Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, شريف مكة, Sharīf Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, شريف الحجاز, Sharīf al-Ḥijāz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

) that did not become a king – was visiting Amman in June and stayed with Hussein in the royal palace. He saw Hussein's management of the affair, and before he left, told his son that he thought Hussein to be the "most genuine, able and courageous Hashemite he had ever met", as well as "the greatest leader among all the Hashemite kings".

Another ceasefire agreement was signed between Hussein and Arafat on 10 July. It recognized and legitimized fedayeen presence in Jordan, and established a committee to monitor fedayeen conduct. The American-sponsored Rogers Plan

The Rogers Plan (also known as Deep Strike) was a framework proposed by United States Secretary of State William P. Rogers to achieve an end to belligerence in the Arab–Israeli conflict following the Six-Day War and the continuing War of Attr ...

for the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, beginning in the mid-20th century. Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, alongside other ef ...

was publicized in July—based on Security Council Resolution 242. Nasser and Hussein accepted the plan, but Arafat rejected it on 26 July, claiming that it was a device to liquidate his movement. The PFLP and DFLP were more uncompromising, vehemently rejecting the plan and denouncing Nasser and Hussein. Meanwhile, a ceasefire was reached between Egypt and Israel on 7 August, formally ending the War of Attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

. On 15 August, Arafat was alleged to have said that "we have decided to convert Jordan into a cemetery for all conspirators—Amman shall be the Hanoi of the revolution." Paradoxically, Arafat had cautioned Habash and Hawatmeh, the respective leaders of the PFLP and the DFLP, from provoking the regime, as it enjoyed military superiority and could terminate their existence in Jordan at any time. But his calls went unheeded, and they started to call more openly for the overthrow of the Hashemites as a "prelude to the launching of a popular war for the liberation of Palestine". Another engagement between the army and the fedayeen occurred at the end of August, after the fedayeen ambushed army vehicles and staged an armed attack on the capital's post office.

Black September

Aircraft hijackings

Hussein's motorcade came under fire on 1 September for the second time in three months, triggering clashes between the army and the fedayeen in Amman up until 6 September. On 6 September, three planes were hijacked by the PFLP:

Hussein's motorcade came under fire on 1 September for the second time in three months, triggering clashes between the army and the fedayeen in Amman up until 6 September. On 6 September, three planes were hijacked by the PFLP: SwissAir

Swissair AG/ S.A. (German: Schweizerische Luftverkehr-AG; French: S.A. Suisse pour la Navigation Aérienne) was the national airline of Switzerland between its founding in 1931 and bankruptcy in 2002.

It was formed from a merger between Bal ...

and TWA

Trans World Airlines (TWA) was a major American airline which operated from 1930 until 2001. It was formed as Transcontinental & Western Air to operate a route from New York City to Los Angeles via St. Louis, Kansas City, and other stops, with ...

jets that landed at Azraq

Azraq ( ar, الأزرق meaning "blue") is a small town in Zarqa Governorate in central-eastern Jordan, east of Amman. The population of Azraq was 9,021 in 2004. The Muwaffaq Salti Air Base is located in Azraq.

History

Prehistory

Archaeolo ...

, Jordan, and a Pan Am

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

jet that was flown to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

and immediately blown up after passengers were deplaned. The two jets that landed in Jordan had 310 passengers; the PFLP threatened to blow them up if fedayeen from European and Israeli prisons were not released. On 9 September, a third plane was hijacked to Jordan: a BOAC

British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the British state-owned airline created in 1939 by the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd. It continued operating overseas services throughout World War II. After the passi ...

flight from Bahrain with 115 passengers was diverted to Zarqa. The PFLP announced that the hijackings were intended "to bring special attention to the Palestinian problem". After 371 hostages were removed, the planes were dramatically blown up in front of international press on 12 September. However, 54 hostages were kept by the organization for around two weeks. Arab regimes and Arafat were not pleased with the hijackings; the latter considered them to have caused more harm to the Palestinian issue. But Arafat could not dissociate himself from the hijackings, again because of Arab public opinion.

Al-Jazy, the perceived pro-Palestinian newly appointed army chief of staff, resigned on 9 September in the midst of the hijacking crisis, and was replaced by

Al-Jazy, the perceived pro-Palestinian newly appointed army chief of staff, resigned on 9 September in the midst of the hijacking crisis, and was replaced by Habis Majali

Habis Majali ( ar, حابس المجالي; 1914 – April 22, 2001) was a Jordanian soldier. Majali served as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the Jordanian Armed Forces from 1958 to 1975, as Minister of Defense from 1967 to 1968, ...

, who was brought in from retirement. Natheer Rasheed, the intelligence director who had been appointed a month earlier, claimed that Al-Jazy was paid 200,000 Jordanian dinar

The Jordanian dinar ( ar, دينار أردني; ISO 4217, code: JOD; unofficially abbreviated as JD) has been the currency of Jordan since 1950. The dinar is divided into 10 dirhams, 100 qirsh (also called piastres) or 1000 fils (currency), fulu ...

s, and that his resignation letter was written by the PLO. Shlaim claims that the prelude consisted of three stages: "conciliation, containment and confrontation". He argues that Hussein was patient so that he could demonstrate that he had done everything he could to avoid bloodshed, and that confrontation only came after all other options had been exhausted, and after public opinion (both international and local) had tipped against the fedayeen.

Jordanian army attacks

On the evening of 15 September, Hussein called in his advisors for an emergency meeting at his Al-Hummar residence on the western outskirts of Amman.

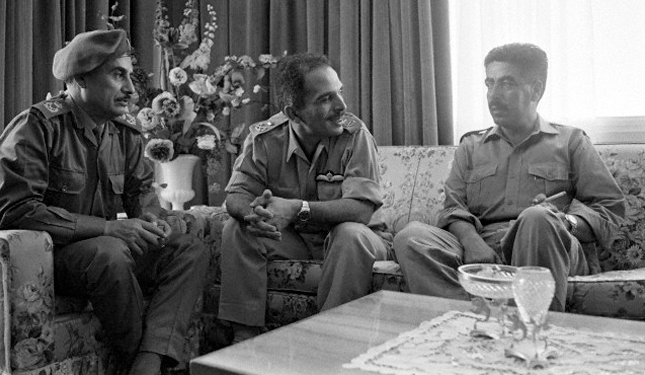

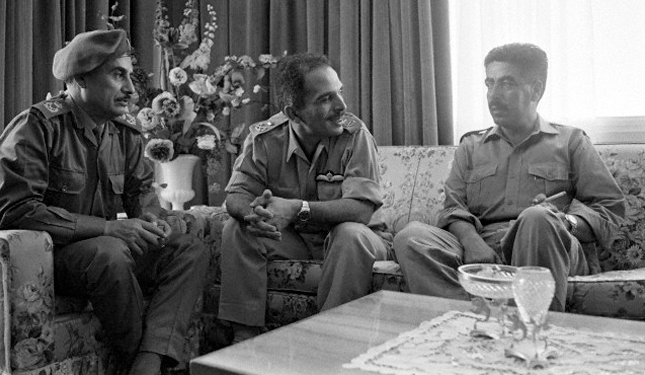

On the evening of 15 September, Hussein called in his advisors for an emergency meeting at his Al-Hummar residence on the western outskirts of Amman. Amer Khammash

Amer Khammash, (born 14 November 1924, in Al-Salt, Transjordan) was a Jordanian Lieutenant General, political and personal adviser to King Hussein of Jordan as well as being His Majesty's Special representative, and being the Chief of The Roya ...

, Habis Majali, Sharif Shaker, Wasfi Tal

Wasfi Tal ( ar, وصفي التل; also known as Wasfi Tell; 19 January 1919 – 28 November 1971) was a Jordanian politician, statesman and general. He served as the 15th Prime Minister of Jordan for three separate terms, 1962–63, 1965–67 a ...

, and Zaid al-Rifai were among those who were present; for some time they had been urging Hussein to sort out the fedayeen. The army generals estimated that it would take two or three days for the army to push the fedayeen out of major cities. Hussein dismissed the civilian government the following day and appointed Muhammad Daoud, a Palestinian loyalist to head a military government, thereby declaring martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. Other Palestinians in the military government included figures like Adnan Abu Oudeh, an officer in the ''mukhabarat''. Abu Oudeh later asked Hussein what the most difficult decision was that he had to make, to which the king replied: "The decision to recapture my capital."

On 17 September, the 60th Armoured Brigade entered the capital Amman from different directions and shelled the Wehdat and Hussein refugee camps where the fedayeen were based with tanks, artillery and mortars. The fedayeen put up a stiff resistance as they were well prepared, and the fighting lasted the next ten days without break. Simultaneously, the army surrounded and attacked other fedayeen-controlled cities including: Irbid, Jerash

Jerash ( ar, جرش ''Ǧaraš''; grc, Γέρασα ''Gérasa'') is a city in northern Jordan. The city is the administrative center of the Jerash Governorate, and has a population of 50,745 as of 2015. It is located north of the capital city ...

, Al-Salt

Al-Salt ( ar, السلط ''As-Salt'') is an ancient salt trading city and administrative centre in west-central Jordan. It is on the old main highway leading from Amman to Jerusalem. Situated in the Balqa (region), Balqa highland, about 790–1, ...

and Zarqa. The three days estimated by Hussein's generals could not be achieved, and the ensuing stalemate led Arab countries to step up pressure on Hussein to halt the fighting.

Foreign intervention

Jordan feared foreign intervention in the events in support of the fedayeen; this soon materialized on 18 September after a force from Syria withPalestine Liberation Army

The Palestine Liberation Army (PLA, ar, جيش التحرير الفلسطيني, ''Jaysh at-Tahrir al-Filastini'') is ostensibly the military wing of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), set up at the 1964 Arab League summit held in A ...

(PLA) markings marched towards Irbid, which the fedayeen had declared a "liberated" city. The 40th Armoured Brigade managed to block the Syrian forces' advance after heavy fighting. A second, much larger, Syrian incursion occurred on the same day: it consisted of two armored and one mechanized infantry brigades of the 5th Infantry Division, and around 300 tanks. Although the Syrian tanks had PLA markings, the troops were Syrian Army regulars. Syria issued no statement regarding the situation, but it is believed that the purpose of its intervention was to help the fedayeen overthrow the monarchy. Another tentative explanation is that the Syrians wanted to create a haven for the fedayeen in northern Jordan, from where they could negotiate with Hussein.

There were also concerns of Iraqi interference. A 17,000-man 3rd Armoured Division of the Iraqi Army had remained in eastern Jordan since after the 1967 Six-Day War. The Iraqi government sympathized with the Palestinians, but it was unclear whether the division would get involved in the conflict in favor of the fedayeen. Thus, the Jordanian 99th Brigade had to be detailed to monitor the Iraqis.

David Raab, one of the plane hijacking hostages, described the initial military actions of Black September:

Hussein arranged a cabinet meeting on the evening of the Syrian incursion, leaving them to decide if Jordan should seek foreign intervention. Two sides emerged from the meeting; one group of ministers favored military intervention from the United Kingdom or the United States, while the other group argued that it was an Arab affair that ought to be dealt with internally. The former group prevailed as Jordan was facing an existential threat. Britain refused to interfere militarily for fear of getting involved in a region-wide conflict; arguments such as "Jordan as it is is not a viable country" emerged. The British cabinet then decided to relay the Hussein's request to the Americans. Nixon and Kissinger were receptive to Hussein's request. Nixon ordered the

There were also concerns of Iraqi interference. A 17,000-man 3rd Armoured Division of the Iraqi Army had remained in eastern Jordan since after the 1967 Six-Day War. The Iraqi government sympathized with the Palestinians, but it was unclear whether the division would get involved in the conflict in favor of the fedayeen. Thus, the Jordanian 99th Brigade had to be detailed to monitor the Iraqis.

David Raab, one of the plane hijacking hostages, described the initial military actions of Black September:

Hussein arranged a cabinet meeting on the evening of the Syrian incursion, leaving them to decide if Jordan should seek foreign intervention. Two sides emerged from the meeting; one group of ministers favored military intervention from the United Kingdom or the United States, while the other group argued that it was an Arab affair that ought to be dealt with internally. The former group prevailed as Jordan was facing an existential threat. Britain refused to interfere militarily for fear of getting involved in a region-wide conflict; arguments such as "Jordan as it is is not a viable country" emerged. The British cabinet then decided to relay the Hussein's request to the Americans. Nixon and Kissinger were receptive to Hussein's request. Nixon ordered the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

's 6th Fleet to be positioned off the coast of Israel, near Jordan. By 19–20 September, the U.S. Navy had concentrated a powerful force in the Eastern Mediterranean. Its official mission was to protect American interests in the region and to respond to the capture of about 54 British, German, and U.S. citizens in Jordan by PLO forces. Later, declassified documents showed that Hussein called an American official at 3 a.m. to request American intervention. "Situation deteriorating dangerously following Syrian massive invasion", Hussein was quoted. "I request immediate physical intervention both land and air... to safeguard sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence of Jordan. Immediate air strikes on invading forces from any quarter plus air cover are imperative." On 22 September, Hussein ordered the Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF) to attack the Syrian forces. A joint air-ground offensive proved successful, contributing to the success was the

On 22 September, Hussein ordered the Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF) to attack the Syrian forces. A joint air-ground offensive proved successful, contributing to the success was the Syrian Air Force

)

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 16 October

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

, battles = * 1948 Arab-Israeli War

* Six-Day War

* Yom Kippur War

* ...

's abstention from joining. This has been attributed to power struggles within the Syrian Ba'athist government between Syrian Assistant Regional Secretary Salah Jadid

Salah Jadid (1926 – 19 August 1993, ar, صلاح جديد, Ṣalāḥ Jadīd) was a Syrian general, a leader of the left-wing of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party in Syria, and the country's ''de facto'' leader from 1966 until 1970, when h ...

and Syrian Air Force commander Hafez Al-Assad. Al-Assad claimed power after a coup on 13 November. Iraqi impartiality was attributed to Iraqi general Hardan Al-Tikriti

Hardan ’Abdul Ghaffar al-Tikriti ( ar, حردان عبدالغفار التكريتي) (1925 – 30 March 1971) was a senior Iraqi Air Force commander, Iraqi politician and ambassador who was assassinated on the orders of Saddam Hussein. Add ...

's commitment to Hussein not to interfere—he was assassinated a year later for this. It is thought that the rivalry between the Iraqi and Syrian Ba'ath Party was the real reason for Iraqi non-involvement.

The airstrikes inflicted heavy losses on the Syrians, and on the late afternoon of 22 September, the Syrian 5th Division began to retreat. A meeting of the Israeli Cabinet on that day was divided on whether or not to intervene in Jordan. King Hussein requested Israeli air support against Syrian forces via the British Embassy in Amman. Israel reluctantly intervened by sending fighter jets to overfly the already retreating Syrian units in a show of support to King Hussein but without engaging. Israeli military commanders had prepared a contingency plan to occupy Jordanian territory–including the Gilead Heights, Karak and Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, العقبة, al-ʿAqaba, al-ʿAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Govern ...

–in case the country disintegrated and there was a land-grab by its Iraqi, Syrian and Saudi Arabian neighbors.

Egyptian brokered agreement

After successes against the Syrian forces, the Jordanian Army steadily shelled the fedayeen's headquarters in Amman, and threatened to also attack them in other regions of the country. The Palestinians suffered heavy losses, and some of their commanders were captured. On the other hand, in the Jordanian army there were around 300 defections, including ranking officers such asMahmoud Da'as

Mahmoud Da'as ( ar, مَحمود دَعّاس, also known by his '' kunya'' Abu Khalid; 1934 – 2009) was a high-ranking commander of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), serving as long-time member of Fatah's Revolutionary Council and Su ...

. Hussein agreed to a cease-fire after Arab media started accusing him of massacring the Palestinians. Jordanian Prime Minister Muhammad Daoud defected to Libya after being pressured by President Muammar Al-Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

, while the former was in Egypt representing Jordan at an emergency Arab League summit. Hussein himself decided to fly to Cairo on 26 September, where he was met with hostility from Arab leaders. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser led the first emergency Arab League summit in Cairo on 21 September. Arafat's speech drew sympathy from attending Arab leaders. Other heads of state took sides against Hussein, among them Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

, who mocked him and his schizophrenic father King Talal

Talal bin Abdullah ( ar, طلال بن عبد الله, ; 26 February 1909 – 7 July 1972) was King of Jordan from the assassination of his father, King Abdullah I, on 20 July 1951 until his forced abdication on 11 August 1952. As a member of ...

. On 27 September, Hussein and Arafat signed an agreement brokered by Egyptian President Nasser. Nasser died the following day of a heart attack. The Jordanian army regained control of key cities and intersections in the country before accepting the ceasefire agreement brokered by Egypt's Nasser. Hussein appointed a Palestinian, Ahmad Toukan, as prime minister, instructing him to "bandage the wounds". In the period following the ceasefire, Hussein publicly revealed that the Jordanian army had uncovered around 360 underground PLO bases in Amman, and that Jordan held 20,000 detainees, among whom were "Chinese advisors".

The Jordanian army regained control of key cities and intersections in the country before accepting the ceasefire agreement brokered by Egypt's Nasser. Hussein appointed a Palestinian, Ahmad Toukan, as prime minister, instructing him to "bandage the wounds". In the period following the ceasefire, Hussein publicly revealed that the Jordanian army had uncovered around 360 underground PLO bases in Amman, and that Jordan held 20,000 detainees, among whom were "Chinese advisors".

Role of Pakistani Zia-ul-Haq and Iranian leftist guerillas

The head of a Pakistani training mission to Jordan, BrigadierMuhammad Zia-ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, (Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial law in ...

(later Chief of Army Staff and President of Pakistan), was involved on the Jordanian side. Zia had been stationed in Amman for three years prior to Black September. During the events, according to CIA official Jack O'Connell Jack O'Connell may refer to:

* Jack O'Connell (actor) (born 1990), English actor

* Jack O'Connell (Australian politician) (1903–1972), member of the Victorian Legislative Council

* Jack O'Connell (diplomat) (1921–2010), American diplomat and C ...

, Zia was dispatched by Hussein north to assess Syria's military capabilities. The Pakistani commander reported back to Hussein, recommending the deployment of a RJAF squadron to the region. O'Connell also said that Zia personally led Jordanian troops during the battles.

Two Iranian leftist guerilla organizations, the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas

The Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG; fa, سازمان چريکهای فدايی خلق ايران, Sāzmān-e čerikhā-ye Fadāʾi-e ḵalq-e Irān), simply known as Fadaiyan-e-Khalq ( fa, فداییان خلق, Fad ...

(OIPFG) and the People's Mujahedin of Iran

The People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI), also known as Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) or Mojahedin-e-Khalq Organization (MKO) ( fa, سازمان مجاهدين خلق ايران, sâzmân-e mojâhedīn-e khalq-e īrân), is an Iranian pol ...

(PMOI), were involved in the conflict against Jordan. Their "collaboration with the PLO was particularly close, and members of both movements even fought side by side in Jordan during the events of Black September and trained together in Fatah camps in Lebanon". On 3 August 1972, PMOI operatives bombed the Jordanian embassy in Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

during King Hussein's state visit as an act of "revenge" for the events of Black September.

Casualties

Arafat claimed that the Jordanian army killed 25,000 Palestinians—other estimates put the number at between 2,000 and 3,400. The Syrian invasion attempt ended with 120 tanks lost, and around 600 Syrian casualties. Jordanian soldiers suffered around 537 dead.Post-September 1970

Another agreement, called the Amman agreement, was signed between Hussein and Arafat on 13 October. It mandated that the fedayeen respect Jordanian sovereignty and desist from wearing uniforms or bearing arms in public. However it contained a clause requiring that Jordan recognize the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinians; Wasfi Tal rejected this clause. Habash and Hawatmeh continued their attacks on the monarchy in spite of the Amman agreement. Hussein appointed Tal to form a government. Tal was seen as anti-Palestinian, however he had made pro-Palestinian gestures during his previous two tenures as prime minister. Tal viewed Arafat with suspicion as he considered that the PLO concentrated its efforts against the Jordanian state rather than against Israel. On one occasion, Tal lost his temper and shouted at Arafat "You are a liar; you don't want to fight Israel!". Shlaim describes Tal as a more uncompromising figure than Hussein, and very popular with the army.

Clashes between the army, and the PFLP and DFLP, ensued after Tal was instated. Tal launched an offensive against fedayeen bases along the Amman-Jerash road in January 1971, and the army drove them out of Irbid in March. In April, Tal ordered the PLO to relocate all its bases from Amman to the forests between Ajloun and Jerash. The fedayeen initially resisted, but they were hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. In July, the army surrounded the last remaining 2,000 fedayeen from the Ajloun-Jerash area. The fedayeen finally surrendered and were allowed to leave to Syria, some 200 fighters preferred to cross the

Another agreement, called the Amman agreement, was signed between Hussein and Arafat on 13 October. It mandated that the fedayeen respect Jordanian sovereignty and desist from wearing uniforms or bearing arms in public. However it contained a clause requiring that Jordan recognize the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinians; Wasfi Tal rejected this clause. Habash and Hawatmeh continued their attacks on the monarchy in spite of the Amman agreement. Hussein appointed Tal to form a government. Tal was seen as anti-Palestinian, however he had made pro-Palestinian gestures during his previous two tenures as prime minister. Tal viewed Arafat with suspicion as he considered that the PLO concentrated its efforts against the Jordanian state rather than against Israel. On one occasion, Tal lost his temper and shouted at Arafat "You are a liar; you don't want to fight Israel!". Shlaim describes Tal as a more uncompromising figure than Hussein, and very popular with the army.

Clashes between the army, and the PFLP and DFLP, ensued after Tal was instated. Tal launched an offensive against fedayeen bases along the Amman-Jerash road in January 1971, and the army drove them out of Irbid in March. In April, Tal ordered the PLO to relocate all its bases from Amman to the forests between Ajloun and Jerash. The fedayeen initially resisted, but they were hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. In July, the army surrounded the last remaining 2,000 fedayeen from the Ajloun-Jerash area. The fedayeen finally surrendered and were allowed to leave to Syria, some 200 fighters preferred to cross the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

to surrender to Israeli forces rather than to the Jordanians. At a 17 July press conference, Hussein declared that Jordanian sovereignty had been completely restored, and that there "was no problem now".

Aftermath

Jordan