Bill Haywood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

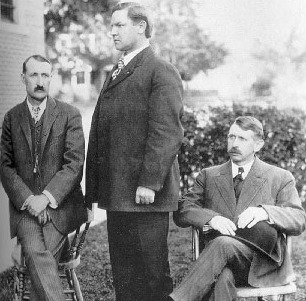

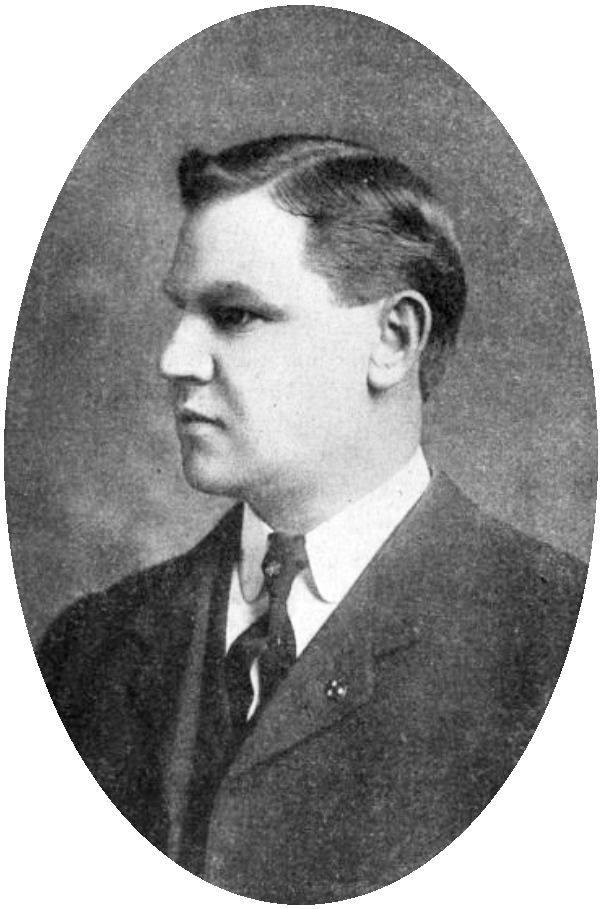

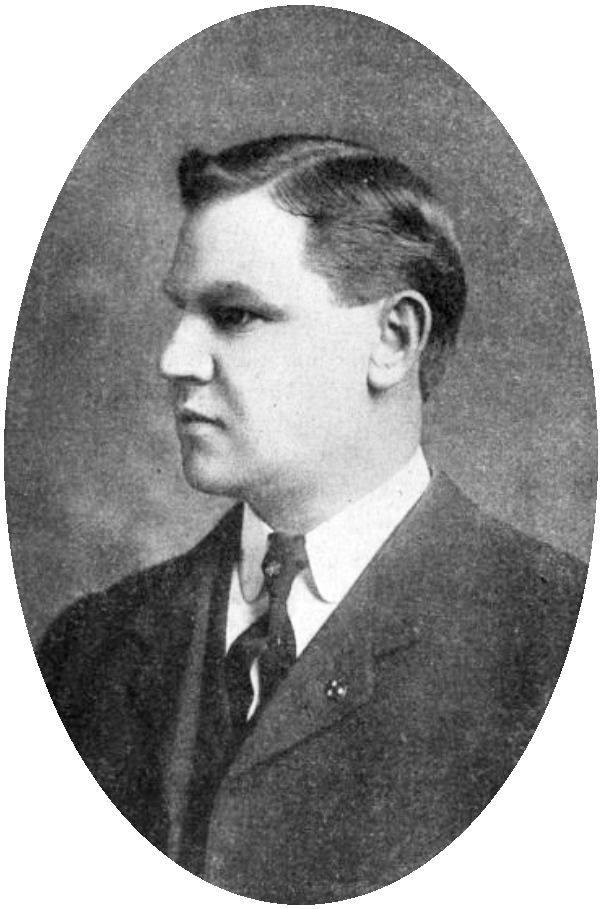

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the

PBS.org; retrieved March 20, 2006. a labor philosophy that favors organizing all workers in an industry under one union, regardless of the specific trade or skill level; this was in contrast to the

"The Trial of Bill Haywood"

His mother Elizabeth was an Episcopalian. At age nine, Haywood injured his right eye while

''The IWW: its History, Structure and Methods.''

Chicago: IWW Publishing Bureau, 1917. A At 10 a.m. on June 27, 1905, Haywood addressed the crowd assembled at Brand's Hall in Chicago.Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States,'' pp. 329–330. In the audience were two hundred delegates from organizations all over the country representing

At 10 a.m. on June 27, 1905, Haywood addressed the crowd assembled at Brand's Hall in Chicago.Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States,'' pp. 329–330. In the audience were two hundred delegates from organizations all over the country representing

On December 30, 1905, Frank Steunenberg was killed by an explosion in front of his house in

On December 30, 1905, Frank Steunenberg was killed by an explosion in front of his house in

Haywood had left the WFM by the time the

Haywood had left the WFM by the time the

"The IWW: Its First 100 Years,"

Industrial Workers of the World, March 2005. When Haywood was quoted speaking at public meetings in New York City to the effect that he had never advocated the use of the ballot by the workers but had instead favored the tactics of direct action, an initiative recalling Haywood from the NEC was launched by the State Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of New York."Result of Referendum D, 1912: Vote Closed February 26

In 1913, Haywood was involved in the Paterson silk strike. He and approximately 1,850 strikers were arrested during the course of the strike. Despite the long holdout and fundraising efforts, the strike ended in failure on July 28, 1913.

In 1913, Haywood was involved in the Paterson silk strike. He and approximately 1,850 strikers were arrested during the course of the strike. Despite the long holdout and fundraising efforts, the strike ended in failure on July 28, 1913.

In January 1915, Haywood replaced Vincent St. John as General Secretary-Treasurer of the IWW, which he held until October 1917. He returned to the position of GST from February 1918 until December of the same year when he was replaced by Peter Stone.

In January 1915, Haywood replaced Vincent St. John as General Secretary-Treasurer of the IWW, which he held until October 1917. He returned to the position of GST from February 1918 until December of the same year when he was replaced by Peter Stone.

''New York Times,'' April 22, 1921, pg. 14. IWW officials were taken by surprise that Haywood had jumped bail, with his own attorney declaring that, "Haywood has committed

In Soviet Russia, Haywood became a labor advisor to

In Soviet Russia, Haywood became a labor advisor to

''New York Times,'' January 14, 1927.

On May 18, 1928, Haywood died in a Moscow hospital from a

On May 18, 1928, Haywood died in a Moscow hospital from a

Debs had been head of the locomotive firemen's union, but he resigned to create the

Debs had been head of the locomotive firemen's union, but he resigned to create the

General Bell had been the manager of one of the coal mines in Cripple Creek where the strike was taking place. It wasn't any surprise to Haywood that soldiers seemed to be working in the interests of the employers; he had seen that situation before. But when the Colorado legislature acknowledged the complaints of organized labor and passed an eight hour law, the Colorado supreme court declared it unconstitutional. So the WFM took the issue to the voters, and 72 percent of the state's voters approved the referendum. But the Colorado government ignored the results of the referendum.

To members of the WFM, it became clear that government favored the companies, and only direct action by organized workers could secure the eight-hour day for themselves. When miners in

General Bell had been the manager of one of the coal mines in Cripple Creek where the strike was taking place. It wasn't any surprise to Haywood that soldiers seemed to be working in the interests of the employers; he had seen that situation before. But when the Colorado legislature acknowledged the complaints of organized labor and passed an eight hour law, the Colorado supreme court declared it unconstitutional. So the WFM took the issue to the voters, and 72 percent of the state's voters approved the referendum. But the Colorado government ignored the results of the referendum.

To members of the WFM, it became clear that government favored the companies, and only direct action by organized workers could secure the eight-hour day for themselves. When miners in

''The Armies of Labor: A Chronicle of the Organized Wage-Earners.''

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1919. Haywood criticized the U.S. government's attempts to turn whites against blacks during the 1899 Coeur d'Alene labor confrontation. Haywood wrote: "it was a deliberate attempt to add race prejudice ... race prejudice had been unknown among the miners."Bill Haywood's Book. 1929, International Publishers. Chapter 5. In 1912, Haywood spoke at a convention for

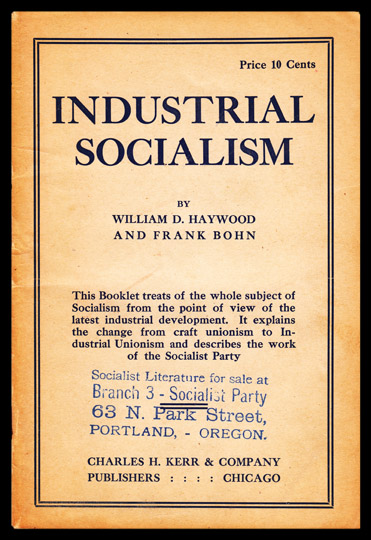

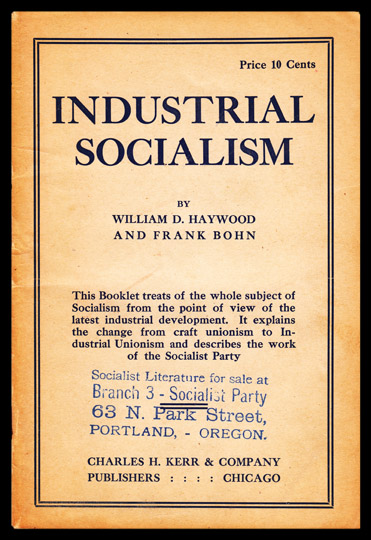

Industrial Socialism

' With Frank Bohn. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1911.

''The General Strike.''

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., n.d.

Speech of William D. Haywood on the Case of Ettor and Giovannitti, 1912.

Bill Haywood Remembers the 1913 Paterson Strike

''With Drops of Blood the History of the Industrial Workers of the World Has Been Written.''

n.c. (Chicago): Industrial Workers of the World, n.d. (1919).

''Raids! Raids!! Raids!!!''

n.c. (Chicago): Industrial Workers of the World, n.d. (Dec. 1919). * ''Bill Haywood's Book: The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood.'' New York: International Publishers, 1929. Reissued as ''The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood.''

"Revolutionary Tendencies in American Labor – Part 2,"

''The American Labor Movement: A New Beginning.'' Resurgence. * * Beverly Gage, ''The Day Wall Street Exploded: The Story of America in its First Age of Terror.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. * Elizabeth Jameson, ''All That Glitters: Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek.'' Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998. * J. Anthony Lukas, '' Big Trouble: A Murder in a Small Western Town Sets Off a Struggle for the Soul of America.'' New York:

"The IWW: Its First 100 Years,"

Industrial Workers of the World, March 2005. * Vincent St. John

''The IWW: its History, Structure and Methods.''

Chicago: IWW Publishing Bureau, 1917. * Fred W. Thompson, ''The IWW: Its First Seventy Years 1905–1975.'' Industrial Workers of the World, 1976. * Bruce Watson, ''Bread and Roses: Mills, Migrants, and The Struggle for the American Dream.'' New York: Viking-Penguin, 2005. * Howard Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States.'' Revised and Updated. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

at

Max Eastman "Bill Haywood, Communist"

David Karsner "William D. Haywood, Communist Ambassador to Russia"

Lewis Gannett "Bill Haywood in Moscow"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Haywood, Bill 1869 births 1928 deaths American communists American defectors to the Soviet Union American trade union leaders American Marxists American miners American people of South African descent American revolutionaries American socialists American syndicalists Burials at Forest Home Cemetery, Chicago Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis 20th-century American people Industrial Workers of the World leaders Industrial Workers of the World members Members of the Socialist Party of America People acquitted of murder People from Salt Lake City People convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917 American anti–World War I activists Progressive Era in the United States People granted political asylum in the Soviet Union Western Federation of Miners people

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

. During the first two decades of the 20th century, Haywood was involved in several important labor battles, including the Colorado Labor Wars, the Lawrence Textile Strike

The Lawrence Textile Strike, also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a ne ...

, and other textile strikes in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

.

Haywood was an advocate of industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a trade union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in ...

,"New Perspectives on the West – William 'Big Bill' Haywood"PBS.org; retrieved March 20, 2006. a labor philosophy that favors organizing all workers in an industry under one union, regardless of the specific trade or skill level; this was in contrast to the

craft union

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

s that were prevalent at the time, such as the AFL

AFL may refer to:

Sports

* American Football League (AFL), a name shared by several separate and unrelated professional American football leagues:

** American Football League (1926) (a.k.a. "AFL I"), first rival of the National Football Leagu ...

.William Cahn, ''A Pictorial History of American Labor.'' New York: Crown Publishers, 1972; pp. 137, 169. He believed that workers of all ethnicities should be united,Howard Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States.'' Revised and Updated. New York: HarperCollins, 2009; pp. 337–39. and favored direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

over political action.

Haywood was often targeted by prosecutors due to his support for violence. An attempt to prosecute him in 1907 for his alleged involvement in the murder of Frank Steunenberg failed, but in 1918 he was one of 101 IWW members jailed for anti-war activity during the First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the R ...

. He was sentenced to twenty years. In 1921, while out of prison during an appeal of his conviction, Haywood fled to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, where he spent the remaining years of his life.

Biography

Early life

Bill Haywood was born in 1869 inSalt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

, Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

. His father, a former Pony Express

The Pony Express was an American express mail service that used relays of horse-mounted riders. It operated from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861, between Missouri and California. It was operated by the Central Overland California and Pike ...

rider, died of pneumonia when Haywood was three years old.Douglas Linder"The Trial of Bill Haywood"

His mother Elizabeth was an Episcopalian. At age nine, Haywood injured his right eye while

whittling

Whittling may refer either to the art of carving shapes out of raw wood using a knife or a time-occupying, non-artistic (contrast wood carving for artistic process) process of repeatedly shaving slivers from a piece of wood. It is used by many as ...

a slingshot with a knife, permanently blinding that eye. He never had his damaged eye replaced with a glass eye; when photographed, he would turn his head to show his left profile. After his uncle Richard arranged for Haywood to work as an indentured laborer on a farm, a job Haywood disliked, he changed his name from William Richard to William Dudley after his father. At age 15, with very little formal education, Haywood began working in the mines. After brief stints as a cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the '' vaqu ...

and a homesteader, he returned to mining in 1896. High-profile events such as the Haymarket Massacre in 1886 and the Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

in 1894 fostered Haywood's interest in the labor movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

.Willam D. Haywood, ''The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood'' (pg. 59). New York: International Publishers, 1966.

Western Federation of Miners involvement

In 1896, Ed Boyce, president of theWestern Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

(WFM), spoke at the Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

silver mine where Haywood was working. Inspired by his speech, Haywood signed up as a WFM member, thus formally beginning his involvement in America's labor movement. He immediately became active in the WFM, and by 1900 he had become a member of the union's General Executive Board. In 1902, he became secretary-treasurer of the WFM, the number two position after President Charles Moyer

Charles H. "Charlie" Moyer (1866 – June 2, 1929) was an American labor leader and president of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) from 1902 to 1926. He led the union through the Colorado Labor Wars, was accused of murdering an ex-govern ...

.

The following year, the WFM became involved in the Colorado Labor Wars, a struggle centered in the Cripple Creek mining district in 1903 and 1904, and took the lives of 33 union and non-union workers. The WFM initiated a series of strikes designed to extend the benefits of the union to other workers. The defeat of these strikes led to Haywood's belief in " One Big Union" organized along industrial lines to bring broader working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

support for labor struggles.

Foundation of the Industrial Workers of the World

Late in 1904, several prominent labor radicals met inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

to lay down plans for a new revolutionary union.For an official account, see: Vincent St. John''The IWW: its History, Structure and Methods.''

Chicago: IWW Publishing Bureau, 1917. A

manifesto

A manifesto is a published declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party or government. A manifesto usually accepts a previously published opinion or public consensus or promotes a ...

was written and sent around the country. Unionists who agreed with the manifesto were invited to attend a convention to found the new union which was to become the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW).

At 10 a.m. on June 27, 1905, Haywood addressed the crowd assembled at Brand's Hall in Chicago.Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States,'' pp. 329–330. In the audience were two hundred delegates from organizations all over the country representing

At 10 a.m. on June 27, 1905, Haywood addressed the crowd assembled at Brand's Hall in Chicago.Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States,'' pp. 329–330. In the audience were two hundred delegates from organizations all over the country representing socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the econ ...

, anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, miners, industrial unionists and rebel workers. Haywood opened the IWW's first convention with the following speech:

Fellow Workers, this is theOther speakers at the convention includedContinental Congress The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...of the working-class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working-class from the slave bondage of capitalism. The aims and objects of this organization shall be to put the working-class in possession of the economic power, the means of life, in control of the machinery of production and distribution, without regard to capitalist masters.

Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

, leader of the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

; Mary Harris "Mother" Jones

Mary G. Harris Jones (1837 (baptized) – November 30, 1930), known as Mother Jones from 1897 onwards, was an Irish-born American schoolteacher and dressmaker who became a prominent union organizer, community organizer, and activist. She h ...

, an organizer for the United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

; and Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marria ...

, a major labor organizer whose husband was hanged in relation to the Haymarket affair. After its foundation, the IWW would become aggressively involved in the labor movement.

Murder trial

On December 30, 1905, Frank Steunenberg was killed by an explosion in front of his house in

On December 30, 1905, Frank Steunenberg was killed by an explosion in front of his house in Caldwell, Idaho

Caldwell (locally CALL-dwel) is a city in and the county seat of Canyon County, Idaho. The population was 59,996 at the time of the 2020 United States census.

Caldwell is considered part of the Boise metropolitan area. Caldwell is the location ...

. A former governor of Idaho

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political r ...

, Steunenberg had clashed with the WFM in previous strikes. Harry Orchard, a former WFM member who had once acted as WFM President Charles Moyer's bodyguardHaywood, ''The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood,'' pg. 158. was arrested for the crime, and evidence was found in his hotel room. Famed Pinkerton detective James McParland, who had infiltrated and helped to destroy the Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires were an Irish people, Irish 19th-century secret society active in Ireland, Liverpool and parts of the Eastern United States, best known for their activism among Irish-American and Irish diaspora, Irish immigrant coal miners i ...

, was placed in charge of the investigation.

Before the trial, McParland ordered that Orchard be placed on death row in the Boise

Boise (, , ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Idaho and is the county seat of Ada County. On the Boise River in southwestern Idaho, it is east of the Oregon border and north of the Nevada border. The downtown area' ...

penitentiary, with restricted food rations and under constant surveillance. After McParland had prepared his investigation, he met with Orchard over a "sumptuous lunch" followed by cigars. The detective reportedly told Orchard that he could escape hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

only if he implicated the leaders of the WFM. In addition to using the threat of hanging, McParland promised food, cigars, better treatment, possible freedom, and even a possible financial reward if Orchard cooperated. The detective obtained a 64-page confession from Orchard in which the suspect took responsibility for a string of crimes and at least seventeen murders.

Extradition

Of the four men named by Orchard as having a part in Steunenberg's murder, Jack Simpkins had fled, and the other three were known to be inDenver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

. The prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the Civil law (legal system), civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the ...

feared that if they knew that Orchard was cooperating with the prosecution, the other three would also flee. At McParland's urging, the three were arrested in Denver on February 17, 1906.

Although none of the three had set foot in Idaho while Orchard was stalking

Stalking is unwanted and/or repeated surveillance by an individual or group toward another person. Stalking behaviors are interrelated to harassment and intimidation and may include following the victim in person or monitoring them. The term ...

Steunenberg and planning his murder, under Idaho law, conspirators were considered to be legally present at the scene of the crime. Using this provision, the local county prosecutor in Idaho drew up extradition

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdi ...

papers for Haywood, Moyer, and George Pettibone

George A. Pettibone (May 1862 – August 3, 1908) was an Idaho miner. Pettibone was best known as a defendant in trial of three leaders of the Western Federation of Miners for the 1905 assassination by bombing of Frank Steunenberg, former governo ...

, which falsely alleged that they had been physically present in Idaho at the time of the murder.

McParland arrived in Denver on Thursday, February 15, and presented the extradition papers to Colorado Governor

The governor of Colorado is the head of government of the U.S. state of Colorado. The governor is the head of the executive branch of Colorado's state government and is charged with enforcing state laws. The governor has the power to either appr ...

Jesse Fuller McDonald, who, by prior arrangement with Idaho Governor Frank R. Gooding

Frank Robert Gooding (September 16, 1859June 24, 1928) was a Republican United States Senator and the seventh governor of Idaho. The city of Gooding and Gooding County, both in southern Idaho, are named for him.

Life and career

Born in the c ...

, accepted them immediately. McParland had planned the arrests for early Sunday morning, when a special train would be ready to take the prisoners to Idaho. The prosecution plans were upset when Moyer went to the Denver train station on Saturday evening carrying a satchel, evidently to leave town. The police arrested him before he could board a train. Moyer's arrest caused the police to move up the arrests of Haywood and Pettibone. The train would not be ready until Sunday morning and so the prisoners were taken to the Denver city jail, but were forbidden from communicating to lawyers or families. Since reporters began nosing around the jail anyway, the prisoners were secretly taken to the Oxford Hotel, near the train station, where they were again held ''incommunicado''. On Sunday morning, the three men were put on the special train, guarded by Colorado militia, which sped out of Denver through Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

, and by nightfall they were in Idaho. To thwart any attempts to free the prisoners, the train sped through the principal towns, and stopped for water and to change engines and crew only at out-of-the-way stations.

Trade union members regarded the incident as a kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

that occurred to extradite them to Idaho before the courts in Denver could intervene. The extradition was so extraordinary that the president of the AFL, Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, directed his union to raise funds for the defense

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indus ...

. However, the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

denied a ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

'' appeal, ruling that the arrest and extradition were legal, with only Justice Joseph McKenna dissenting.

While in jail in Idaho, Haywood was put forth by the Socialist Party of Colorado as their candidate in the 1906 Colorado gubernatorial election. He finished with over 16,000 votes, just under eight percent.

Trial

Haywood's trial began on May 9, 1907, with famed Chicago defense attorneyClarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

defending him. The government had only the testimony of Orchard, the confessed bomber, to implicate Haywood and the other defendants, and Orchard's checkered past and admitted violent history were skillfully exploited by Darrow during the trial, though he did not lead Orchard's cross-examination

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and ...

. During the trial, Orchard admitted that he had acted as a paid informant of the Mine Owners' Association In the United States, a Mine Owners' Association (MOA), also sometimes referred to as a Mine Operators' Association or a Mine Owners' Protective Association, is the combination of individual mining companies, or groups of mining companies, into an ...

, in effect working for both sides. He also admitted to accepting money from Pinkerton detectives, and had caused explosions during mining disputes before he had met Moyer or Haywood.

After Darrow's final summation, the jury retired on July 28, 1907. After deliberating nine hours, the jury returned on July 29 and acquitted Haywood. During the subsequent trial of Pettibone, Darrow conducted a powerful cross-examination against Orchard before falling ill and withdrawing from the trial, leaving Orrin N. Hilton of Denver to head the defense. After a second jury acquitted Pettibone, the charges against Moyer were dropped.

Despite his radical views, Haywood emerged from the trial with a national reputation. Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

called him "the Lincoln of Labor." Along with his colorful background and appearance, Haywood was known for his blunt statements about capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

. "The capitalist has no heart," he often said, "but harpoon him in the pocketbook and you will draw blood." Another time, he began a speech by noting, "Tonight I am going to speak on the class struggle and I am going to make it so plain that even a lawyer can understand it." Yet Haywood also had a flair for dangerous hyperbole that, when quoted in newspapers, was used to justify wholesale arrests of IWW strikers. "Confiscate! That's good!" he often said. "I like that word. It suggests stripping the capitalist, taking something away from him. But there has got to be a good deal of force to this thing of taking."

When the WFM withdrew from the IWW in 1907, Haywood remained a member of both organizations. His murder trial had made Haywood a celebrity, and he was in demand as a speaker for the WFM. But his increasingly radical speeches became more at odds with the WFM, and in April 1908, the union announced that they had ended Haywood's role as a WFM representative. Haywood left the WFM and devoted all his time to organizing for the IWW.

Lawrence Textile Strike

Haywood had left the WFM by the time the

Haywood had left the WFM by the time the Lawrence Textile Strike

The Lawrence Textile Strike, also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a ne ...

in Lawrence, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, garnered national attention. On January 11, 1912, textile mill workers in Lawrence left their jobs in protest of lowered wages. Within a week, twenty thousand workers were on strike. Authorities responded by calling out police, and the strike quickly escalated into violence. Local IWW leaders Joseph Ettor

Joseph James "Smiling Joe" Ettor (1885–1948) was an Italian-American trade union organizer who, in the middle-1910s, was one of the leading public faces of the Industrial Workers of the World. Ettor is best remembered as a defendant in a contr ...

and Arturo Giovannitti

Arturo M. Giovannitti (; 1884–1959) was an Italian-American union leader, socialist political activist, and poet. He is best remembered as one of the principal organizers of the 1912 Lawrence textile strike and as a defendant in a celebrated tr ...

were jailed on charges of murdering Anna LoPizzo Anna LoPizzo was an Italian immigrant striker killed during the Lawrence Textile Strike (also known as the Bread and Roses Strike), considered one of the most significant struggles in U.S. labor history. Eugene Debs said of the strike, "The Victor ...

, a striker whom nineteen witnesses later said was killed by police gunfire, and martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

was declared. In response, Haywood and other organizers arrived to take charge of the strike.

Over the next several weeks, Haywood personally masterminded or approved many of the strike's tactical innovations. Chief among these was his decision to send strikers' hungry children to sympathetic families in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, and Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

. After hearing from immigrants how European strikers had used this tactic during prolonged strikes, Haywood decided to take the gamble in Lawrence, a first in American labor history. He and the IWW used announcements in socialist newspapers to solicit host families, then screened strikers to see who might be willing to send their children into the care of strangers. On February 10, 1912, the first group of "Lawrence Strike Children" bid tearful goodbyes to their parents and, with chaperones to guide them, boarded a train for New York. The children arrived safely in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

that evening where they were taken to a meeting hall. They were soon lavished with food and clothes and would stay in New York another seven weeks. Despite their excellent treatment, officials in Lawrence and elsewhere were shocked by the move. "I could scarcely believe that the strike leaders would do such a thing as this," Lawrence mayor Michael Scanlon said. "Lawrence could have very easily cared for these children."

On February 24, when strikers attempted to send still more children away, police were ready. During a melée, women and children were forcibly separated, police lashed out with clubs, and dozens of strikers and their children were jailed. A national outrage resulted. The ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'' wrote, "The Lawrence authorities must be blind and the mill owners mad."Watson, ''Bread and Roses,'' pg. 175. The ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' called the police response "as chuckle-headed an exhibition of incompetence to deal with a strike situation as it is possible to recall." The incident led to a congressional hearing and the attention of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. Nationwide publicity pressured the mill owners into cooperating with the strikers; on March 12, the owners agreed to all the demands of the strikers, officially ending the strike.

However, Haywood and the IWW were not yet finished in Lawrence; despite the success of the strike, Ettor and Giovannitti remained in prison. Haywood threatened the authorities with another strike, saying, "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates." Legal efforts and a one-day strike on September 30 did not prompt the authorities to drop the charges. Haywood was indicted

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of ...

in Lawrence for misuse of strike funds, a move that kept him from returning to the city and eventually led to his arrest on the Boston Common

The Boston Common (also known as the Common) is a public park in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest city park in the United States. Boston Common consists of of land bounded by Tremont Street (139 Tremont St.), Park Street, Beac ...

. However, on November 26, Ettor and Giovannitti were acquitted, and upon their release were treated to a massive demonstration of public support.

Socialist Party of America involvement

For many years, Haywood was an active member of theSocialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

. Haywood had always been largely Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

in his political views, and campaigned for Debs during the 1908 presidential election, traveling by train with Debs around the country.Sam Dolgoff, "Revolutionary Tendencies in American Labor – Part 2," ''The American Labor Movement: A New Beginning.'' Resurgence. Haywood also represented the Socialist Party as a delegate to the 1910 congress of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

, an organization working towards international socialism. In 1912, he was elected to the Socialist Party National Executive Committee.

However, the aggressive tactics of Haywood and the IWW, along with their call for abolition of the wage system and the overthrow of capitalism, created tension with moderate, electorally-oriented leaders of the Socialist Party. Haywood and the IWW focused on direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

and strikes, which often led to violence, and were less concerned with political tactics.Harry Siitonen"The IWW: Its First 100 Years,"

Industrial Workers of the World, March 2005. When Haywood was quoted speaking at public meetings in New York City to the effect that he had never advocated the use of the ballot by the workers but had instead favored the tactics of direct action, an initiative recalling Haywood from the NEC was launched by the State Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of New York."Result of Referendum D, 1912: Vote Closed February 26

913

__NOTOC__

Year 913 ( CMXIII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* June 6 – Emperor Alexander III dies of exhaustion while playing ...

" ''Cleveland Socialist,'' vol. 2, whole no. 73 (March 15, 1913), pg. 4. In February 1913 the recall of Haywood was approved by a margin of more than 2-to-1. Following his defeat, Haywood left the ranks of the Socialist Party, joined by thousands of other IWW members and their sympathizers.

Other labor involvement

In 1913, Haywood was involved in the Paterson silk strike. He and approximately 1,850 strikers were arrested during the course of the strike. Despite the long holdout and fundraising efforts, the strike ended in failure on July 28, 1913.

In 1913, Haywood was involved in the Paterson silk strike. He and approximately 1,850 strikers were arrested during the course of the strike. Despite the long holdout and fundraising efforts, the strike ended in failure on July 28, 1913.

In January 1915, Haywood replaced Vincent St. John as General Secretary-Treasurer of the IWW, which he held until October 1917. He returned to the position of GST from February 1918 until December of the same year when he was replaced by Peter Stone.

In January 1915, Haywood replaced Vincent St. John as General Secretary-Treasurer of the IWW, which he held until October 1917. He returned to the position of GST from February 1918 until December of the same year when he was replaced by Peter Stone.

Espionage trial

Haywood and the IWW frequently clashed with the government during their labor actions. The onset ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

gave the federal government the opportunity to take action against Haywood and the IWW.Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States,'' pp. 372–373. Using the newly passed Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

as justification, the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

raided forty-eight IWW meeting halls on September 5, 1917. The Department of Justice, with the approval of President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, then proceeded to arrest 165 IWW members for "conspiring to hinder the draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes."

In April 1918, Haywood and 100 of the arrested IWW members began their trial, presided over by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball from 1920 until his death. He is remembered for his ...

. The trial lasted five months, the longest criminal trial up to that time; Haywood himself testified for three days. All 101 defendants were found guilty, and Haywood (along with fourteen others) was sentenced to twenty years in prison.

Despite the efforts of his supporters, Haywood was unable to overturn the conviction. In 1921, he skipped bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

while out on appeal and fled to the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. "Haywood in Russia as Sentence Begins,"''New York Times,'' April 22, 1921, pg. 14. IWW officials were taken by surprise that Haywood had jumped bail, with his own attorney declaring that, "Haywood has committed

hara-kiri

, sometimes referred to as hara-kiri (, , a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honour but was also practised by other Japanese people ...

so far as the labor movement is concerned if he has really run away. He will be disowned by the IWW and all sympathizers." A bond in the amount of $15,000 posted by millionaire supporter William Bross Lloyd was forfeited as a result of Haywood's flight.

Life in Soviet Russia

In Soviet Russia, Haywood became a labor advisor to

In Soviet Russia, Haywood became a labor advisor to Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

's Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

government, and served in that position until 1923. Haywood also participated in the founding of the Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony

The Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony was an experiment in workers' control in the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1926 during the New Economic Policy. It was based in Shcheglovsk, Kuzbass, Siberia.

History Creation of the Autonomous Industrial C ...

. Various visitors to Haywood's small Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

apartment in later years recalled that he felt lonely and depressed, and expressed a desire to return to the U.S. In 1926 he took a Russian wife, though the two had to communicate in sign language

Sign languages (also known as signed languages) are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning, instead of spoken words. Sign languages are expressed through manual articulation in combination with non-manual markers. Sign ...

, as neither spoke the other's language."Big Bill Haywood Weds. Can't Speak Russian and Russian Wife Can't Speak English,"''New York Times,'' January 14, 1927.

Death

On May 18, 1928, Haywood died in a Moscow hospital from a

On May 18, 1928, Haywood died in a Moscow hospital from a stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

brought on by alcoholism and diabetes. Half of his ashes were buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis was the national cemetery for the Soviet Union. Burials in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolshevik individuals who died during the Moscow Bolshevik Uprising were buried in ma ...

; an urn containing the other half of his ashes was sent to Chicago and buried near the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument

The ''Haymarket Martyrs' Monument'' is a funeral monument and sculpture located at Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Dedicated in 1893, it commemorates the defendants involved in labor unrest who were blamed, con ...

.

Haywood's labor philosophy

Industrial unionism

Even before Haywood first became an official with the WFM, he was convinced that the system under which working people toiled was unjust. He described the execution of the Haymarket leaders in 1887 as a turning point in his life, predisposing him toward membership in the largest organization of the day, theKnights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

. Haywood had watched men die in unsafe mine tunnels, and had marched with Coxey's Army

Coxey's Army was a protest march by unemployed workers from the United States, led by Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey. They marched on Washington, D.C. in 1894, the second year of a four-year economic depression that was the worst in United Sta ...

. Haywood had suffered a serious hand injury in the mines, and found that his only support came from other miners. When Haywood listened to Ed Boyce of the WFM addressing a group of miners in 1896, he discovered radical unionism and welcomed it.

Haywood also shared Boyce's skepticism of the role played by the AFL. He criticized labor officials who were, in his view, insufficiently supportive of labor militants. For example, Haywood recalled with disdain the opening remarks of Samuel Gompers when the AFL leader appeared before Illinois Governor

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

Richard Oglesby

Richard James Oglesby (July 25, 1824April 24, 1899) was an American soldier and Republican politician from Illinois, The town of Oglesby, Illinois, is named in his honor, as is an elementary school situated in the Auburn Gresham neighborho ...

on behalf of the Haymarket prisoners:

I have differed all my life with the principles and methods of the condemned.Gompers was an advocate of

craft unionism

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

, the idea that workers should be separated into unions according to their skills. The AFL disdained to organize workers who were not skilled. Furthermore, in 1900, Gompers became the first vice-president of the National Civic Federation

The National Civic Federation (NCF) was an American economic organization founded in 1900 which brought together chosen representatives of big business and organized labor, as well as consumer advocates in an attempt to ameliorate labor disputes. I ...

, which was "dedicated to the fostering of harmony and collaboration between capital and organized labor." But Haywood had become convinced by the experiences of striking railroad workers that a different union philosophy, some form of industrial unionism, was necessary for workers to obtain justice. This had become apparent in 1888 when the craft-organized locomotive firemen kept their engines running, helping their employers to break a strike called by the railroad engineers.

Debs had been head of the locomotive firemen's union, but he resigned to create the

Debs had been head of the locomotive firemen's union, but he resigned to create the American Railway Union

The American Railway Union (ARU) was briefly among the largest labor unions of its time and one of the first industrial unions in the United States. Launched at a meeting held in Chicago in February 1893, the ARU won an early victory in a strike ...

(ARU), organized industrially to include all railroad workers. In June 1894, the ARU voted to join in solidarity with the ongoing Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

. Railroad traffic throughout the nation was "largely paralyzed. The effectiveness of the industrial form of unionism was evident from the start." The strike was eventually crushed by massive government intervention that included 2600 Deputy U.S. Marshals, and 14,000 state and federal troops in Chicago alone. Debs attempted to seek help from the AFL, asking that AFL railroad brotherhood affiliates present the following proposition to the Railway Managers' Association:

...that the strikers return to work at once as a body, upon the condition that they be restored to their former positions, or, in the event of failure, to call a general strike.The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929, pp. 77–78.Observing that the ARU was defenseless, AFL officials viewed the plight of the rival organization as an opportunity to bolster the railway brotherhoods, which the AFL was courting, and instructed all AFL affiliates to withhold help. In spite of what Haywood perceived as "treachery" and "double-cross" by the AFL leadership — the ARU members had put their own organization at risk for others, but the AFL refused to even help them try to end the strike in a draw — the power of workers crossing their trade lines and jurisdictional boundaries to join together in a fight against capital greatly impressed him. He described the revelation of such power as "a great rift of light." For Haywood, industrial union principles were later confirmed by the defeat of the WFM in the 1903–05 Cripple Creek strike due — he believed — to insufficient labor solidarity. The WFM miners had sought to extend the benefits of union to the mill workers who processed their ore. Since the government had crushed the ARU, the railroad workers were again organized along craft lines, similar to the AFL. Those same railroad unions continued to haul the ore ''from mines'' that were run by strike breakers, ''to mills'' that were run by strike breakers. "The railroaders form the connecting link in the proposition that is scabby at both ends," Haywood complained. "This fight, which is entering its third year, could have been won in three weeks if it were not for the fact that the trade unions are lending assistance to the mine operators." The obvious solution, it seemed to Haywood, was for all of the workers to join the same union, and to take collective action in concert against the employers. The militants of the WFM referred to the AFL as the "American ''Separation'' of Labor," a criticism that was later echoed by the IWW.

Haywood's revolutionary imperative

Haywood's industrial unionism was much broader than formulating a more effective method of conducting strikes. Haywood grew up a part of theworking class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

, and his respect for working people was genuine. He was quickly angered by the arrogance of employers "who had never ... spoken to a workingman except to give orders." Having met Debs during his WFM days, Haywood had also become interested in the former railway leader's new passion, socialism. Haywood subscribed to the belief, and with Boyce, formulated as a new motto for the WFM, that:

Labor produces all wealth; all wealth belongs to the producer thereof.Haywood observed how the government frequently took the side of business to defeat the tactics and the aspirations of the miners. During an 1899 organizing drive in

Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

Coeur d'Alene ( ; french: Cœur d'Alène, lit=Heart of an Awl ) is a city and the county seat of Kootenai County, Idaho, United States. It is the largest city in North Idaho and the principal city of the Coeur d'Alene Metropolitan Statistica ...

, with pay cuts as a motivating issue, the company hired spies and then fired organizers and pro-union miners. Some frustrated miners responded with violence and when two men were killed, martial law was declared. As they had done in a strike in Coeur d'Alene seven years earlier, soldiers acted as strike breakers. They rounded up hundreds of union members without formal charges and put them in a filthy, vermin-infested warehouse without sanitation services for a year. They were so crowded that the soldiers locked the overflow of prisoners in boxcar

A boxcar is the North American (AAR) term for a railroad car that is enclosed and generally used to carry freight. The boxcar, while not the simplest freight car design, is considered one of the most versatile since it can carry most ...

s. One local union leader was imprisoned for 17 years.

Haywood considered the brutal conditions in Coeur d'Alene a manifestation of class warfare

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The for ...

. In 1901 the miners agreed at the WFM convention that a "complete revolution of social and economic conditions" was "the only salvation of the working classes."

In the WFM's 1903–1904 struggle in Colorado, with martial law once again in force, two declarations uttered by the National Guard and recorded for posterity further clarified the relationship of the mine operator's enforcement army—provided courtesy of the Colorado governor—to the workers. When union attorneys asked the courts to free illegally imprisoned strikers, Adjutant General Sherman Bell

Adjutant General Sherman M. Bell was a controversial leader of the Colorado Army National Guard, Colorado National Guard during the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903–04. While Bell received high praise from Theodore Roosevelt and others, he was vilif ...

declared, "Habeas corpus be damned, we'll give 'em post mortems." Reminded of the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, one of Bell's junior officers declared coolly, "To hell with the Constitution. We're not going by the Constitution."

General Bell had been the manager of one of the coal mines in Cripple Creek where the strike was taking place. It wasn't any surprise to Haywood that soldiers seemed to be working in the interests of the employers; he had seen that situation before. But when the Colorado legislature acknowledged the complaints of organized labor and passed an eight hour law, the Colorado supreme court declared it unconstitutional. So the WFM took the issue to the voters, and 72 percent of the state's voters approved the referendum. But the Colorado government ignored the results of the referendum.

To members of the WFM, it became clear that government favored the companies, and only direct action by organized workers could secure the eight-hour day for themselves. When miners in

General Bell had been the manager of one of the coal mines in Cripple Creek where the strike was taking place. It wasn't any surprise to Haywood that soldiers seemed to be working in the interests of the employers; he had seen that situation before. But when the Colorado legislature acknowledged the complaints of organized labor and passed an eight hour law, the Colorado supreme court declared it unconstitutional. So the WFM took the issue to the voters, and 72 percent of the state's voters approved the referendum. But the Colorado government ignored the results of the referendum.

To members of the WFM, it became clear that government favored the companies, and only direct action by organized workers could secure the eight-hour day for themselves. When miners in Idaho Springs

The City of Idaho Springs is the Statutory City that is the most populous municipality in Clear Creek County, Colorado, United States. Idaho Springs is a part of the Denver–Aurora–Lakewood, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 201 ...

and Telluride decided to strike for the eight-hour day, they were rounded up at gunpoint by vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

groups and expelled from their communities. Warrants were issued for the arrest of the law-breaking vigilantes, but they were not acted upon.

Haywood complained that John D. Rockefeller was "wielding more power with his golf sticks than could the people of Colorado with their ballots." It appeared to Haywood that the deck was stacked, and no enduring gains could be won for the workers short of changing the rules of the game. Increasingly, his industrial unionism took on a revolutionary flavor. In 1905 Haywood joined the more left-leaning socialists, labor anarchists in the Haymarket tradition, and other militant unionists to formulate the concept of revolutionary industrial unionism that animated the IWW. Haywood called this philosophy "socialism with its working clothes on."

Haywood favored direct action. The socialist philosophy — which WFM supporter the Rev. Fr. Thomas J. Hagerty

Thomas Joseph Hagerty (ca. 1862–1920s?) was an American Roman Catholic priest and trade union activist. Hagerty is remembered as one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), as author of the influential Preamble to t ...

called ''"slowcialism"'' — did not seem hard-nosed enough for Haywood's labor instincts. After the Boise murder trial, he had come to believe,

It is to the ignominy of the Socialist Party and theWhile Haywood continued to champion direct action, he advocated the political action favored by the socialists as just one more mechanism for change, and only when it seemed relevant. At an October 1913 meeting of the Socialist Party, Haywood stated:Socialist Labor Party The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...that they have so seldom joined forces with the I.W.W. in these desperate political struggles.

I advocate the industrial ballot alone when I address the workers in the textile industries of the East where a great majority are foreigners without political representation. But when I speak to American workingmen in the West I advocate both the industrial and the political ballot.Helen MarotThe "industrial ballot" referred to the direct action methods (strikes, slowdowns, etc.) of the IWW. Haywood seemed most comfortable with a philosophy arrived at through the hard-scrabble experiences of the workers. He had the ability to translate complex economic theories into simple ideas that resonated with working people. He distilled the voluminous work of

''American Labor Unions: By a Member.''

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1914; Chapter 4.

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

into a simple observation, "If one man has a dollar he didn't work for, some other man worked for a dollar he didn't get." While Haywood respected the work of Marx, he referred to it with irreverent humor. Acknowledging his scars from dangerous mining work, and from numerous fistfights with police and militia, he liked to say, "I've never read Marx's Capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

, but I have the marks of capital all over me."

Haywood demonstrated his Marxist roots when, confronted by the Commission on Industrial Relations

The Commission on Industrial Relations (also known as the Walsh Commission) p. 12. was a commission created by the U.S. Congress on August 23, 1912, to scrutinize US labor law. The commission studied work conditions throughout the industrial Uni ...

with an argument about the sanctity of private property, he responded that a capitalist's property merely represented "unpaid labor, surplus value

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to the owner of that product to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cos ...

." But the forum also gave Haywood an opportunity to compare the philosophy of the IWW with that of Marx and the socialist parties. Reminded by the Commission that socialists advocated ownership of the industries by the state, Haywood remembered in his autobiography that he had drawn a clear distinction. All of industry should be owned "by the workers," he observed.

Racial unity in the labor movement

Much of Haywood's philosophy relating to socialism, preferring industrial unionism, his perception of the evils of the wage system, and his attitude about corporations, militias, and politicians seems to have been held in common with his WFM mentor Ed Boyce. Boyce also called for legislation to forbid employment of aliens. Unlike Boyce and many other labor leaders and organizations of the time, Haywood believed that workers of all ethnicities should organize into the same union. According to Haywood, the IWW was "big enough to take in the black man, the white man; big enough to take in all nationalities – an organization that will be strong enough to obliterate state boundaries; to obliterate national boundaries."Quoted in Samuel Orth''The Armies of Labor: A Chronicle of the Organized Wage-Earners.''

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1919. Haywood criticized the U.S. government's attempts to turn whites against blacks during the 1899 Coeur d'Alene labor confrontation. Haywood wrote: "it was a deliberate attempt to add race prejudice ... race prejudice had been unknown among the miners."Bill Haywood's Book. 1929, International Publishers. Chapter 5. In 1912, Haywood spoke at a convention for

The Brotherhood of Timber Workers

The Brotherhood of Timber Workers (BTW) (1910-1916) was a union of sawmill workers, farmers, and small business people primarily located in East Texas and West Louisiana, but also had locals in Arkansas (7) and Mississippi (1). The BTW was organiz ...

in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

; at the time, interracial meetings in the state were illegal. Haywood insisted that the white workers invite the African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

workers to their convention, declaring:

You work in the same mills together. Sometimes a black man and a white man chop down the same tree together. You are meeting in a convention now to discuss the conditions under which you labor. Why not be sensible about this and call the Negroes into the Convention? If it is against the law, this is one time when the law should be broken.Ignoring the law against interracial meetings, the convention invited the African American workers. The convention would eventually vote to affiliate with the IWW.

Works

*Industrial Socialism

' With Frank Bohn. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1911.

''The General Strike.''

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., n.d.

911

911 or 9/11 may refer to:

Dates

* AD 911

* 911 BC

* September 11

** 9/11, the September 11 attacks of 2001

** 11 de Septiembre, Chilean coup d'état in 1973 that outed the democratically elected Salvador Allende

* November 9

Numbers

* 911 ...

Speech of March 16, 1911.

Speech of William D. Haywood on the Case of Ettor and Giovannitti, 1912.

Bill Haywood Remembers the 1913 Paterson Strike

''With Drops of Blood the History of the Industrial Workers of the World Has Been Written.''

n.c. (Chicago): Industrial Workers of the World, n.d. (1919).

''Raids! Raids!! Raids!!!''

n.c. (Chicago): Industrial Workers of the World, n.d. (Dec. 1919). * ''Bill Haywood's Book: The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood.'' New York: International Publishers, 1929. Reissued as ''The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood.''

See also

*Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

*Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

*1913 Paterson Silk Strike

The 1913 Paterson silk strike was a work stoppage involving silk mill workers in Paterson, New Jersey. The strike involved demands for establishment of an eight-hour day and improved working conditions. The strike began in February 1913, and ende ...

*International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was activ ...

* Are You Going To Hang My Papa?

Footnotes

Further reading

* * Joseph R. Conlin, ''Big Bill Haywood and the Radical Union Movement.'' Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969. * Sam Dolgoff"Revolutionary Tendencies in American Labor – Part 2,"

''The American Labor Movement: A New Beginning.'' Resurgence. * * Beverly Gage, ''The Day Wall Street Exploded: The Story of America in its First Age of Terror.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. * Elizabeth Jameson, ''All That Glitters: Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek.'' Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998. * J. Anthony Lukas, '' Big Trouble: A Murder in a Small Western Town Sets Off a Struggle for the Soul of America.'' New York:

Simon and Schuster

Simon & Schuster () is an American publishing company and a subsidiary of Paramount Global. It was founded in New York City on January 2, 1924 by Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. As of 2016, Simon & Schuster was the third largest pub ...

, 1997.

* Harry Siitonen"The IWW: Its First 100 Years,"

Industrial Workers of the World, March 2005. * Vincent St. John

''The IWW: its History, Structure and Methods.''

Chicago: IWW Publishing Bureau, 1917. * Fred W. Thompson, ''The IWW: Its First Seventy Years 1905–1975.'' Industrial Workers of the World, 1976. * Bruce Watson, ''Bread and Roses: Mills, Migrants, and The Struggle for the American Dream.'' New York: Viking-Penguin, 2005. * Howard Zinn, ''A People's History of the United States.'' Revised and Updated. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

External links

at

marxists.org

Marxists Internet Archive (also known as MIA or Marxists.org) is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich En ...

*

Max Eastman "Bill Haywood, Communist"

David Karsner "William D. Haywood, Communist Ambassador to Russia"

Lewis Gannett "Bill Haywood in Moscow"