Bessemer converter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive

The Japanese may have made use of a Bessemer-type process, which was observed by European travellers in the 17th century. The adventurer Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo describes the process in a book published in English in 1669. He writes, "They have, among others, particular invention for the melting of iron, without the using of fire, casting it into a tun done about on the inside without about half a foot of earth, where they keep it with continual blowing, take it out by ladles full, to give it what form they please." According to historian Donald Wagner, Mandelslo did not personally visit Japan, so his description of the process is likely derived from accounts of other Europeans who had traveled to Japan. Wagner believes that the Japanese process may have been similar to the Bessemer process, but cautions that alternative explanations are also plausible.

The Japanese may have made use of a Bessemer-type process, which was observed by European travellers in the 17th century. The adventurer Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo describes the process in a book published in English in 1669. He writes, "They have, among others, particular invention for the melting of iron, without the using of fire, casting it into a tun done about on the inside without about half a foot of earth, where they keep it with continual blowing, take it out by ladles full, to give it what form they please." According to historian Donald Wagner, Mandelslo did not personally visit Japan, so his description of the process is likely derived from accounts of other Europeans who had traveled to Japan. Wagner believes that the Japanese process may have been similar to the Bessemer process, but cautions that alternative explanations are also plausible.

In the early to mid-1850s, the American inventor William Kelly experimented with a method similar to the Bessemer process. Wagner

writes that Kelly may have been inspired by techniques introduced by Chinese ironworkers hired by Kelly in 1854. The claim that both Kelly and Bessemer invented the same process remains controversial. When Bessemer's patent for the process was reported by '' Scientific American'', Kelly responded by writing a letter to the magazine. In the letter, Kelly states that he had previously experimented with the process and claimed that Bessemer knew of Kelly's discovery. He wrote that "I have reason to believe my discovery was known in England three or four years ago, as a number of English puddlers visited this place to see my new process. Several of them have since returned to England and may have spoken of my invention there." It is suggested Kelly's process was less developed and less successful than Bessemer's process.

In the early to mid-1850s, the American inventor William Kelly experimented with a method similar to the Bessemer process. Wagner

writes that Kelly may have been inspired by techniques introduced by Chinese ironworkers hired by Kelly in 1854. The claim that both Kelly and Bessemer invented the same process remains controversial. When Bessemer's patent for the process was reported by '' Scientific American'', Kelly responded by writing a letter to the magazine. In the letter, Kelly states that he had previously experimented with the process and claimed that Bessemer knew of Kelly's discovery. He wrote that "I have reason to believe my discovery was known in England three or four years ago, as a number of English puddlers visited this place to see my new process. Several of them have since returned to England and may have spoken of my invention there." It is suggested Kelly's process was less developed and less successful than Bessemer's process.

Bessemer licensed the patent for his process to four

Bessemer licensed the patent for his process to four

''The Times-Tribune,'' 11 July 2010, accessed 23 May 2016 Bessemer steel was used in the United States primarily for railroad rails. During the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, a major dispute arose over whether

Using the Bessemer process, it took between 10 and 20 minutes to convert three to five tons of iron into steel — it would previously take at least a full day of heating, stirring and reheating to achieve this.

Using the Bessemer process, it took between 10 and 20 minutes to convert three to five tons of iron into steel — it would previously take at least a full day of heating, stirring and reheating to achieve this.

By the early 19th century the puddling process was widespread. Until technological advances made it possible to work at higher heats,

By the early 19th century the puddling process was widespread. Until technological advances made it possible to work at higher heats,

In 1898, '' Scientific American'' published an article called ''Bessemer Steel and its Effect on the World'' explaining the significant economic effects of the increased

In 1898, '' Scientific American'' published an article called ''Bessemer Steel and its Effect on the World'' explaining the significant economic effects of the increased

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process

Industrial processes are procedures involving chemical, physical, electrical or mechanical steps to aid in the manufacturing of an item or items, usually carried out on a very large scale. Industrial processes are the key components of heavy ind ...

for the mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batc ...

of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation with air being blown through the molten iron. The oxidation also raises the temperature of the iron mass and keeps it molten.

Related decarburizing with air processes had been used outside Europe for hundreds of years, but not on an industrial scale. One such process (similar to puddling) was known in the 11th century in East Asia, where the scholar Shen Kuo of that era described its use in the Chinese iron and steel industry. In the 17th century, accounts by European travelers detailed its possible use by the Japanese.

The modern process is named after its inventor, the Englishman Henry Bessemer, who took out a patent on the process in 1856. The process was said to be independently discovered in 1851 by the American inventor William Kelly though the claim is controversial.

The process using a basic refractory

In materials science, a refractory material or refractory is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat, pressure, or chemical attack, and retains strength and form at high temperatures. Refractories are polycrystalline, polyphase, ...

lining is known as the "basic Bessemer process" or Gilchrist–Thomas process

The Gilchrist–Thomas process or Thomas process is a historical process for refining pig iron, derived from the Bessemer converter. It is named after its inventors who patented it in 1877: Percy Carlyle Gilchrist and his cousin Sidney Gilchrist ...

after the English discoverers Percy Gilchrist

Percy Carlyle Gilchrist FRS (27 December 1851 – 16 December 1935) was a British chemist and metallurgist.

Life

Gilchrist was born in Lyme Regis, Dorset, the son of Alexander and Anne Gilchrist and studied at Felsted and the Royal School o ...

and Sidney Gilchrist Thomas.

History

Early history

A system akin to the Bessemer process has existed since the 11th century in East Asia. Economic historian Robert Hartwell writes that the Chinese of the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) innovated a "partial decarbonization" method of repeated forging ofcast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

under a cold blast. Sinologist Joseph Needham and historian of metallurgy Theodore A. Wertime have described the method as a predecessor to the Bessemer process of making steel. This process was first described by the prolific scholar and polymath government official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) in 1075, when he visited Cizhou. Hartwell states that perhaps the earliest center where this was practiced was the great iron-production district along the Henan– Hebei border during the 11th century.

In the 15th century, the finery process, another process which shares the air-blowing principle with the Bessemer process, was developed in Europe. In 1740, Benjamin Huntsman

Benjamin Huntsman (4 June 170420 June 1776) was an English inventor and manufacturer of cast or crucible steel.

Biography

Huntsman was born the fourth child of William and Mary (née Nainby) Huntsman, a Quaker farming couple, in Epworth, Linc ...

developed the crucible technique

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

for steel manufacture, at his workshop in the district of Handsworth in Sheffield. This process had an enormous impact on the quantity and quality of steel production, but it was unrelated to the Bessemer-type process employing decarburization.

Bessemer's patent

In the early to mid-1850s, the American inventor William Kelly experimented with a method similar to the Bessemer process. Wagner

writes that Kelly may have been inspired by techniques introduced by Chinese ironworkers hired by Kelly in 1854. The claim that both Kelly and Bessemer invented the same process remains controversial. When Bessemer's patent for the process was reported by '' Scientific American'', Kelly responded by writing a letter to the magazine. In the letter, Kelly states that he had previously experimented with the process and claimed that Bessemer knew of Kelly's discovery. He wrote that "I have reason to believe my discovery was known in England three or four years ago, as a number of English puddlers visited this place to see my new process. Several of them have since returned to England and may have spoken of my invention there." It is suggested Kelly's process was less developed and less successful than Bessemer's process.

In the early to mid-1850s, the American inventor William Kelly experimented with a method similar to the Bessemer process. Wagner

writes that Kelly may have been inspired by techniques introduced by Chinese ironworkers hired by Kelly in 1854. The claim that both Kelly and Bessemer invented the same process remains controversial. When Bessemer's patent for the process was reported by '' Scientific American'', Kelly responded by writing a letter to the magazine. In the letter, Kelly states that he had previously experimented with the process and claimed that Bessemer knew of Kelly's discovery. He wrote that "I have reason to believe my discovery was known in England three or four years ago, as a number of English puddlers visited this place to see my new process. Several of them have since returned to England and may have spoken of my invention there." It is suggested Kelly's process was less developed and less successful than Bessemer's process.

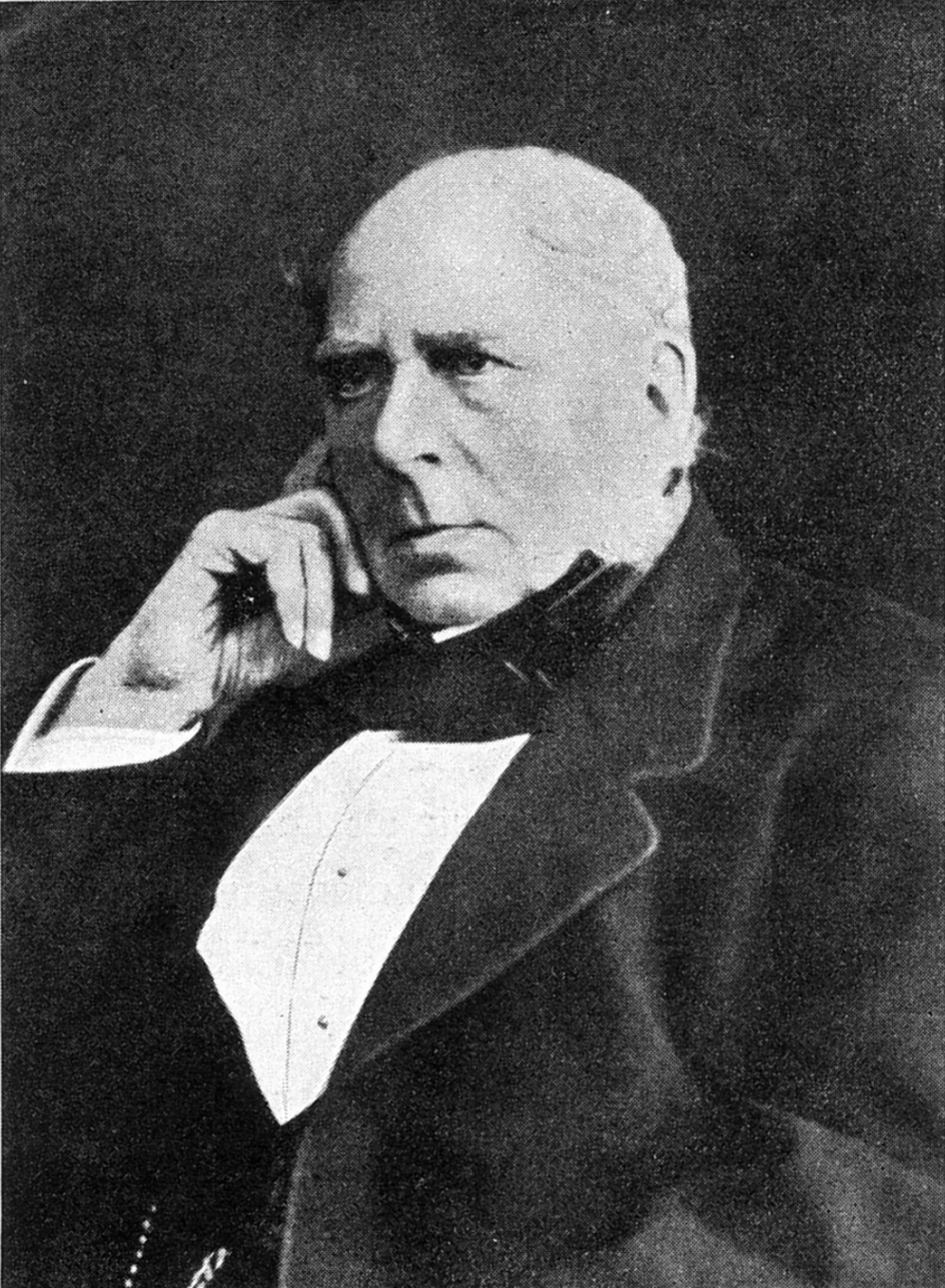

Sir Henry Bessemer

Sir Henry Bessemer (19 January 1813 – 15 March 1898) was an English inventor, whose steel-making process would become the most important technique for making steel in the nineteenth century for almost one hundred years from 1856 to 1950. He ...

described the origin of his invention in his autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

written in 1890. During the outbreak of the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, many English industrialists and inventors became interested in military technology. According to Bessemer, his invention was inspired by a conversation with Napoleon III in 1854 pertaining to the steel required for better artillery. Bessemer claimed that it "was the spark which kindled one of the greatest revolutions that the present century had to record, for during my solitary ride in a cab that night from Vincennes to Paris, I made up my mind to try what I could to improve the quality of iron in the manufacture of guns." At the time, steel was used to make only small items like cutlery and tools, but was too expensive for cannons. Starting in January 1855, he began working on a way to produce steel in the massive quantities required for artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, ...

and by October he filed his first patent related to the Bessemer process. He patented the method a year later in 1856.

Bessemer licensed the patent for his process to four

Bessemer licensed the patent for his process to four ironmaster

An ironmaster is the manager, and usually owner, of a forge or blast furnace for the processing of iron. It is a term mainly associated with the period of the Industrial Revolution, especially in Great Britain.

The ironmaster was usually a large ...

s, for a total of £27,000, but the licensees failed to produce the quality of steel he had promised—it was "rotten hot and rotten cold", according to his friend, William Clay—and he later bought them back for £32,500. His plan had been to offer the licenses to one company in each of several geographic areas, at a royalty price per ton that included a lower rate on a proportion of their output in order to encourage production, but not so large a proportion that they might decide to reduce their selling prices. By this method he hoped to cause the new process to gain in standing and market share.

He realised that the technical problem was due to impurities in the iron and concluded that the solution lay in knowing when to turn off the flow of air in his process so that the impurities were burned off but just the right amount of carbon remained. However, despite spending tens of thousands of pounds on experiments, he could not find the answer. Certain grades of steel are sensitive to the 78% nitrogen which was part of the air blast passing through the steel.

The solution was first discovered by English metallurgist Robert Forester Mushet

Robert Forester Mushet (8 April 1811 – 29 January 1891) was a British metallurgist and businessman, born on 8 April 1811, in Coleford, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. He was the youngest son of Scottish parents, Agnes Wilson ...

, who had carried out thousands of experiments in the Forest of Dean. His method was to first burn off, as far as possible, ''all'' the impurities and carbon, then reintroduce carbon and manganese by adding an exact amount of spiegeleisen, an alloy of iron and manganese with trace amounts of carbon and silicon. This had the effect of improving the quality of the finished product, increasing its malleability—its ability to withstand rolling and forging at high temperatures and making it more suitable for a vast array of uses. Mushet's patent ultimately lapsed due to Mushet's inability to pay the patent fees and was acquired by Bessemer. Bessemer earned over 5 million dollars in royalties from the patents.

The first company to license the process was the Manchester firm of W & J Galloway, and they did so before Bessemer announced it at Cheltenham in 1856. They are not included in his list of the four to whom he refunded the license fees. However, they subsequently rescinded their license in 1858 in return for the opportunity to invest in a partnership with Bessemer and others. This partnership began to manufacture steel in Sheffield from 1858, initially using imported charcoal pig iron from Sweden. This was the first commercial production.

A 20% share in the Bessemer patent was also purchased for use in Sweden and Norway by Swedish trader and Consul Göran Fredrik Göransson

Göran Fredrik Göransson (20 January 1819 – 12 May 1900) was a Swedish merchant, ironmaster and industrialist. He was the founder of the company ''Sandvikens Jernverks AB'' (now called Sandvik AB) and was the first person to implement the Bes ...

during a visit to London in 1857. During the first half of 1858, Göransson, together with a small group of engineers, experimented with the Bessemer process at Edsken near Hofors

Hofors () is a locality and the seat of Hofors Municipality, Gävleborg County, Sweden with 6,681 inhabitants in 2010.

Districts

*Born

*Böle

*Bönhusberget

*Centrum

*Göklund

*Hammaren

*Lillån

*Muntebo

*Rönningen

*Silverda ...

, Sweden before he finally succeeded. Later in 1858 he again met with Henry Bessemer in London, managed to convince him of his success with the process, and negotiated the right to sell his steel in England. Production continued in Edsken, but it was far too small for the industrial-scale production needed. In 1862 Göransson built a new factory for his Högbo Iron and Steel Works company on the shore of Lake Storsjön, where the town of Sandviken was founded. The company was renamed Sandviken's Ironworks, continued to grow and eventually became Sandvik

Sandvik AB is a Swedish multinational engineering company specializing in metal cutting, digital and additive manufacturing, mining and construction, stainless and special steel alloys, and industrial heating. The company was founded in Swe ...

in the 1970s.

Industrial revolution in the United States

Alexander Lyman Holley

Alexander Lyman Holley (Lakeville, Connecticut, July 20, 1832 – Brooklyn, New York, January 29, 1882) was an American mechanical engineer, inventor, and founding member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). He was consider ...

contributed significantly to the success of Bessemer steel in the United States. His ''A Treatise on Ordnance and Armor

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes'' ...

'' is an important work on contemporary weapons manufacturing and steel-making practices. In 1862, he visited Bessemer's Sheffield works, and became interested in licensing the process for use in the US. Upon returning to the US, Holley met with two iron producers from Troy, New York, John F. Winslow

John Flack Winslow (November 10, 1810 – March 10, 1892) was an American businessman and iron manufacturer who was the fifth president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Life

He was born on November 10, 1810, in Bennington, Vermont, and wa ...

and John Augustus Griswold

John Augustus Griswold (November 11, 1818 – October 31, 1872) was an American businessman and politician from New York. He served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1869.

Early life

Griswold was born on November ...

, who asked him to return to the United Kingdom and negotiate with the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

on their behalf. Holley secured a license for Griswold and Winslow to use Bessemer's patented processes and returned to the United States in late 1863.

The trio began setting up a mill in Troy, New York in 1865. The factory contained a number of Holley's innovations that greatly improved productivity over Bessemer's factory in Sheffield, and the owners gave a successful public exhibition in 1867. The Troy factory attracted the attention of the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

, which wanted to use the new process to manufacture steel rail. It funded Holley's second mill as part of its Pennsylvania Steel subsidiary. Between 1866 and 1877, the partners were able to license a total of 11 Bessemer steel mills.

One of the investors they attracted was Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

, who saw great promise in the new steel technology after a visit to Bessemer in 1872, and saw it as a useful adjunct to his existing businesses, the Keystone Bridge Company

Keystone or key-stone or ''variation'', may refer to:

* Keystone (architecture), a central stone or other piece at the apex of an arch or vault

* Keystone (cask), a fitting used in ale casks

Business

* Keystone Law, a full-service law firm

* ...

and the Union Iron Works. Holley built the new steel mill for Carnegie, and continued to improve and refine the process. The new mill, known as the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, opened in 1875, and started the growth of the United States as a major world steel producer. Using the Bessemer process, Carnegie Steel

Carnegie Steel Company was a steel-producing company primarily created by Andrew Carnegie and several close associates to manage businesses at steel mills in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area in the late 19th century. The company was formed ...

was able to reduce the costs of steel railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

rails from $100 per ton to $50 per ton between 1873 and 1875. The price of steel continued to fall until Carnegie was selling rails for $18 per ton by the 1890s. Prior to the opening of Carnegie's Thomson Works, steel output in the United States totaled around 157,000 tons per year. By 1910, American companies were producing 26 million tons of steel annually.

William Walker Scranton

William Walker Scranton (April 4, 1844 – December 3, 1916) was an American businessman based in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He became president and manager of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company after his father's death in 1872. The company ...

, manager and owner of the Lackawanna Iron & Coal Company in Scranton, Pennsylvania

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the largest city in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming Va ...

, had also investigated the process in Europe. He built a mill in 1876 using the Bessemer process for steel rails and quadrupled his production.Cheryl A. Kashuba, "William Walker led industry in the city"''The Times-Tribune,'' 11 July 2010, accessed 23 May 2016 Bessemer steel was used in the United States primarily for railroad rails. During the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, a major dispute arose over whether

crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fir ...

should be used instead of the cheaper Bessemer steel. In 1877, Abram Hewitt

Abram Stevens Hewitt (July 31, 1822January 18, 1903) was an American politician, educator, ironmaking industrialist, and lawyer who was mayor of New York City for two years from 1887–1888. He also twice served as a U.S. Congressman from and ...

wrote a letter urging against the use of Bessemer steel in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is a hybrid cable-stayed/suspension bridge in New York City, spanning the East River between the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Opened on May 24, 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first fixed crossing of the East River ...

. Bids had been submitted for both crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fir ...

and Bessemer steel; John A. Roebling's Sons submitted the lowest bid for Bessemer steel, but at Hewitt's direction, the contract was awarded to J. Lloyd Haigh Co.

''J. The Jewish News of Northern California'', formerly known as ''Jweekly'', is a weekly print newspaper in Northern California, with its online edition updated daily. It is owned and operated by San Francisco Jewish Community Publications In ...

Technical details

Using the Bessemer process, it took between 10 and 20 minutes to convert three to five tons of iron into steel — it would previously take at least a full day of heating, stirring and reheating to achieve this.

Using the Bessemer process, it took between 10 and 20 minutes to convert three to five tons of iron into steel — it would previously take at least a full day of heating, stirring and reheating to achieve this.

Oxidation

The blowing of air through the molten pig iron introduces oxygen into the melt which results in oxidation, removing impurities found in the pig iron, such as silicon, manganese, and carbon in the form of oxides. These oxides either escape as gas or form a solidslag

Slag is a by-product of smelting ( pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-pr ...

. The refractory lining of the converter also plays a role in the conversion — clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay parti ...

linings may be used when there is little phosphorus in the raw material, and Bessemer himself used ganister

A ganister (or sometimes gannister ) is hard, fine-grained quartzose sandstone, or orthoquartzite,Jackson, J. A., 1997, ''Glossary of geology'', 4th ed. American Geological Institute, Alexandria. used in the manufacture of silica brick typically ...

sandstone – this is known as the ''acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

Bessemer'' process. When the phosphorus content is high, dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

, or sometimes magnesite, linings are required in the basic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College i ...

Bessemer limestone process, see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

* Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

*Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

*Fred Below ...

. In order to produce steel with desired properties, additives such as spiegeleisen (a ferromanganese alloy), can be added to the molten steel once the impurities have been removed.

Managing the process

When the required steel had been formed, it was poured into ladles and then transferred into moulds while the lighter slag was left behind. The conversion process, called the "blow", was completed in approximately 20 minutes. During this period, the progress of the oxidation of the impurities was judged by the appearance of the flame issuing from the mouth of the converter. The modern use of photoelectric methods of recording the characteristics of the flame greatly aided the blower in controlling final product quality. After the blow, the liquid metal was recarburized to the desired point and other alloying materials were added, depending on the desired product. A Bessemer converter could treat a "heat" (batch of hot metal) of 5 to 30 tons at a time. They were usually operated in pairs, one being blown while another was being filled or tapped.Predecessor processes

By the early 19th century the puddling process was widespread. Until technological advances made it possible to work at higher heats,

By the early 19th century the puddling process was widespread. Until technological advances made it possible to work at higher heats, slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting ( pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-pr ...

impurities could not be removed entirely, but the reverberatory furnace made it possible to heat iron without placing it directly in the fire, offering some degree of protection from the impurity of the fuel source. Thus, with the advent of this technology, coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dead ...

began to replace charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

fuel. The Bessemer process allowed steel to be produced without fuel, using the impurities of the iron to create the necessary heat. This drastically reduced the costs of steel production, but raw material

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feedst ...

s with the required characteristics could be difficult to find.

High-quality steel was made by the reverse process of adding carbon to carbon-free wrought iron, usually imported from Sweden. The manufacturing process, called the cementation process

The cementation process is an obsolete technology for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcote Steel F ...

, consisted of heating bars of wrought iron together with charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

for periods of up to a week in a long stone box. This produced blister steel

The cementation process is an obsolete technology for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcote Steel F ...

. The blister steel was put in a crucible with wrought iron and melted, producing crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fir ...

. Up to 3 tons of expensive coke was burnt for each ton of steel produced. Such steel when rolled into bars was sold at £50 to £60 (approximately £3,390 to £4,070 in 2008) a long ton. The most difficult and work-intensive part of the process, however, was the production of wrought iron done in finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery ...

s in Sweden.

This process was refined in the 18th century with the introduction of Benjamin Huntsman

Benjamin Huntsman (4 June 170420 June 1776) was an English inventor and manufacturer of cast or crucible steel.

Biography

Huntsman was born the fourth child of William and Mary (née Nainby) Huntsman, a Quaker farming couple, in Epworth, Linc ...

's crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fir ...

-making techniques, which added an additional three hours firing time and required additional large quantities of coke. In making crucible steel, the blister steel bars were broken into pieces and melted in small crucibles, each containing 20 kg or so. This produced higher quality crucible steel but increased the cost. The Bessemer process reduced the time needed to make steel of this quality to about half an hour while requiring only the coke needed initially to melt the pig iron. The earliest Bessemer converters produced steel for £7 a long ton, although it initially sold for around £40 a ton.

"Basic" vs. acidic Bessemer process

Sidney Gilchrist Thomas, a Londoner with a Welsh father, was an industrial chemist who decided to tackle the problem of phosphorus in iron, which resulted in the production of low grade steel. Believing that he had discovered a solution, he contacted his cousin,Percy Gilchrist

Percy Carlyle Gilchrist FRS (27 December 1851 – 16 December 1935) was a British chemist and metallurgist.

Life

Gilchrist was born in Lyme Regis, Dorset, the son of Alexander and Anne Gilchrist and studied at Felsted and the Royal School o ...

, who was a chemist at the Blaenavon Ironworks. The manager at the time, Edward Martin, offered Sidney equipment for large-scale testing and helped him draw up a patent that was taken out in May 1878. Sidney Gilchrist Thomas's invention consisted of using dolomite or sometimes limestone linings for the Bessemer converter rather than clay, and it became known as the 'basic' Bessemer rather than the 'acid' Bessemer process. An additional advantage was that the processes formed more slag in the converter, and this could be recovered and used very profitably as a phosphate fertilizer.

Importance

supply

Supply may refer to:

*The amount of a resource that is available

**Supply (economics), the amount of a product which is available to customers

**Materiel, the goods and equipment for a military unit to fulfill its mission

*Supply, as in confidenc ...

in cheap steel. They noted that the expansion of railroads into previously sparsely inhabited regions of the country had led to settlement in those regions, and had made the trade of certain goods profitable, which had previously been too costly to transport.

The Bessemer process revolutionized steel manufacture by decreasing its cost, from £40 per long ton to £6–7 per long ton, along with greatly increasing the scale and speed of production of this vital raw material. The process also decreased the labor requirements for steel-making. Before it was introduced, steel was far too expensive to make bridges or the framework for buildings and thus wrought iron had been used throughout the Industrial Revolution. After the introduction of the Bessemer process, steel and wrought iron became similarly priced, and some users, primarily railroads, turned to steel. Quality problems, such as brittleness caused by nitrogen in the blowing air, prevented Bessemer steel from being used for many structural applications. Open-hearth steel was suitable for structural applications.

Steel greatly improved the productivity of railroads. Steel rails lasted ten times longer than iron rails. Steel rails, which became heavier as prices fell, could carry heavier locomotives, which could pull longer trains. Steel rail cars were longer and were able to increase the freight to car weight from 1:1 to 2:1.

As early as 1895 in the UK it was being noted that the heyday of the Bessemer process was over and that the open hearth

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to produce steel. Because steel is difficult to manufacture owing to its high me ...

method predominated. The ''Iron and Coal Trades Review'' said that it was "in a semi-moribund condition. Year after year, it has not only ceased to make progress, but it has absolutely declined." It has been suggested, both at that time and more recently, that the cause of this was the lack of trained personnel and investment in technology rather than anything intrinsic to the process itself. For example, one of the major causes of the decline of the giant ironmaking company Bolckow Vaughan

Bolckow, Vaughan & Co., Ltd was an English steelmaking, ironmaking and mining company founded in 1864, based on the partnership since 1840 of its two founders, Henry Bolckow and John Vaughan (ironmaster), John Vaughan. The firm drove the dramat ...

of Middlesbrough was its failure to upgrade its technology. The basic process, the Thomas-Gilchrist process, remained in use longer, especially in Continental Europe, where iron ores were of high phosphorus content and the open-hearth process was not able to remove all phosphorus; almost all inexpensive construction steel in Germany was produced with this method in the 1950s and 1960s. It was eventually superseded by basic oxygen steelmaking.

Obsolescence

In the U.S., commercial steel production using this method stopped in 1968. It was replaced by processes such as the basic oxygen (Linz–Donawitz) process, which offered better control of final chemistry. The Bessemer process was so fast (10–20 minutes for a heat) that it allowed little time for chemical analysis or adjustment of the alloying elements in the steel. Bessemer converters did not remove phosphorus efficiently from the molten steel; as low-phosphorus ores became more expensive, conversion costs increased. The process permitted only limited amount of scrap steel to be charged, further increasing costs, especially when scrap was inexpensive. Use of electric arc furnace technology competed favourably with the Bessemer process resulting in its obsolescence. Basic oxygen steelmaking is essentially an improved version of the Bessemer process (decarburization by blowing oxygen as gas into the heat rather than burning the excess carbon away by adding oxygen carrying substances into the heat). The advantages of pure oxygen blast over air blast were known to Henry Bessemer, but 19th-century technology was not advanced enough to allow for the production of the large quantities of pure oxygen necessary to make it economical.See also

* Cementation (metallurgy) process * Methods of crucible steel productionReferences

Bibliography

*External links

* * * {{Iron and steel production English inventions Steelmaking Metallurgical processes Economic history of the United States