Berlin Conference on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European

Prior to the conference, European diplomats approached governments in Africa in the same manner as they did in the Western Hemisphere by establishing a connection to local trade networks. In the early 1800s, the European demand for

Prior to the conference, European diplomats approached governments in Africa in the same manner as they did in the Western Hemisphere by establishing a connection to local trade networks. In the early 1800s, the European demand for

here

origina

here

but these 14 countries sent representatives to attend the Berlin Conference and sign the subsequent Berlin Act: /a> 26 February 1885. Uniquely, the United States reserved the right to decline or to accept the conclusions of the conference.

Discovering Collection

The first name of this Society had been the " International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa". * The properties occupied by Belgian King Leopold's

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

period and coincided with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

's sudden emergence as an imperial power. The conference was organized by Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of Germany. Its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, can be seen as the formalisation of the Scramble for Africa, but some historians warn against an overemphasis of its role in the colonial partitioning of Africa, and draw attention to bilateral agreements concluded before and after the conference. The conference contributed to ushering in a period of heightened colonial activity by European powers, which eliminated or overrode most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance. Of the fourteen countries being represented, six of them – Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Sweden–Norway, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

– came home without any formal possessions in Africa.

Background

Prior to the conference, European diplomats approached governments in Africa in the same manner as they did in the Western Hemisphere by establishing a connection to local trade networks. In the early 1800s, the European demand for

Prior to the conference, European diplomats approached governments in Africa in the same manner as they did in the Western Hemisphere by establishing a connection to local trade networks. In the early 1800s, the European demand for ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

, which was then often used in the production of luxury goods, led many European merchants into the interior markets of Africa. European spheres of power and influence were limited to coastal Africa at this time as Europeans had only established trading posts (protected by gunboats) up to this point.

In 1876, King Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

, who had founded and controlled the International African Association

The International African Association (in full, "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa"; in French ''Association Internationale Africaine,'' and in full ''Association Internationale pour l'Exploration et ...

the same year, invited Henry Morton Stanley to join him in researching and "civilizing" the continent. In 1878, the International Congo Society

The International Association of the Congo (french: Association internationale du Congo), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Con ...

was also formed, with more economic goals but still closely related to the former society. Leopold secretly bought off the foreign investors in the Congo Society, which was turned to imperialistic

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic

...

goals, with the "African Society" serving primarily as a philanthropic front.

From 1878 to 1885, Stanley returned to the Congo not as a reporter but as Leopold's agent, with the secret mission to organise what would become known as the Congo Free State soon after the closure of the Berlin Conference in August 1885. French agents discovered Leopold's plans, and in response France sent its own explorers to Africa. In 1881, French naval officer Pierre de Brazza was dispatched to central Africa, travelled into the western Congo basin, and raised the French flag over the newly founded Brazzaville in what is now the Republic of Congo. Finally, Portugal, which had essentially abandoned a colonial empire in the area, long held through the mostly defunct proxy Kingdom of Kongo, also claimed the area, based on old treaties with Restoration-era Spain and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. It quickly made a treaty on 26 February 1884 with its former ally, Great Britain, to block off the Congo Society's access to the Atlantic.

By the early 1880s, many factors including diplomatic successes, greater European local knowledge, and the demand for resources such as gold, timber, and rubber, triggered dramatically increased European involvement in the continent of Africa. Stanley's charting of the Congo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharge ...

Basin (1874–1877) removed the last from European maps of the continent, delineating the areas of British, Portuguese, French and Belgian control. These European nations raced to annex territory that might be claimed by rivals.

France moved to take over Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, one of the last of the Barbary states, using a claim of another piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

incident. French claims by Pierre de Brazza were quickly acted on by the French military, which took control of what is now the Republic of the Congo in 1881 and Guinea in 1884. Italy became part of the Triple Alliance, an event that upset Bismarck's carefully laid plans and led Germany to join the European invasion of Africa.

In 1882, realizing the geopolitical extent of Portuguese control on the coasts, but seeing penetration by France eastward across Central Africa toward Ethiopia, the Nile, and the Suez Canal, Britain saw its vital trade route through Egypt to India threatened. Under the pretext of the collapsed Egyptian financing and a subsequent mutiny in which hundreds of British subjects were murdered or injured, Britain intervened in the nominally Ottoman Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, which it controlled for decades.

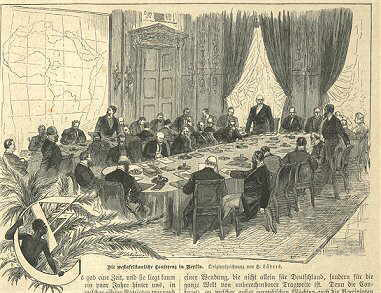

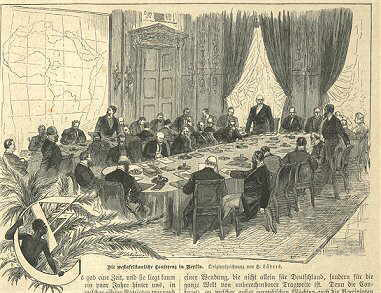

Conference

The European race for colonialism made Germany start launching expeditions of its own, which frightened both British and French statesmen. Hoping to quickly soothe the brewing conflict, Belgian King Leopold II convinced France and Germany that common trade in Africa was in the best interests of all three countries. Under support from the British and the initiative of Portugal, Otto von Bismarck, the Chancellor of Germany, called on representatives of 13 nations in Europe as well as the United States to take part in the Berlin Conference in 1884 to work out a joint policy on the African continent. The conference was opened on 15 November 1884, and continued until it closed on 26 February 1885. The number ofplenipotentiaries

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word ' ...

varied per nation, Also availablhere

origina

here

but these 14 countries sent representatives to attend the Berlin Conference and sign the subsequent Berlin Act: /a> 26 February 1885. Uniquely, the United States reserved the right to decline or to accept the conclusions of the conference.

General Act

The General Act fixed the following points: * Partly to gain public acceptance, the conference resolved to end slavery by African and Islamic powers. Thus, an international prohibition of the slave trade throughout their respected spheres was signed by the European members. In his novella '' Heart of Darkness'', Joseph Conrad sarcastically referred to one of the participants at the conference, theInternational Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (french: Association internationale du Congo), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Con ...

(also called "International Congo Society"), as "the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs"."Historical Context: ''Heart of Darkness''." EXPLORING Novels, Online Edition. Gale, 2003Discovering Collection

The first name of this Society had been the " International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa". * The properties occupied by Belgian King Leopold's

International Congo Society

The International Association of the Congo (french: Association internationale du Congo), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Con ...

, the name used in the General Act, were confirmed as the Society's. On 1 August 1885, a few months after the closure of the Berlin Conference, Leopold's Vice-Administrator General in the Congo, Francis de Winton, announced that the territory was henceforth called "the Congo Free State", a name that in fact was not in use at the time of the conference and does not appear in the General Act. The Belgian official ''Law Gazette'' later stated that from that same 1 August 1885 onwards, Leopold II was to be considered "Sovereign" of the new state, again an issue never discussed, let alone decided, at the Berlin Conference.

* The 14 signatory powers would have free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

throughout the Congo Basin as well as Lake Malawi

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, is an African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

It is the fifth largest fr ...

and east of it in an area south of 5° N.

* The Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesCongo rivers were made free for ship traffic.

* The Principle of Effective Occupation (based on "effective occupation", see below) was introduced to prevent powers from setting up colonies in name only.

* Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a

The conference provided an opportunity to channel latent European hostilities towards one another outward; provide new areas for helping the European powers expand in the face of rising American, Russian and Japanese interests; and form constructive dialogue to limit future hostilities. In Africa, colonialism was introduced across nearly all the continent. When African independence was regained after World War II, it was in the form of fragmented states.

The Scramble for Africa sped up after the Conference since even within areas designated as their sphere of influence, the European powers had to take effective possession by the principle of effectivity. In central Africa in particular, expeditions were dispatched to coerce traditional rulers into signing treaties, using force if necessary, such as was the case for Msiri, King of Katanga, in 1891. Bedouin- and Berber-ruled states in the Sahara and the Sahel were overrun by the French in several wars by the beginning of

The conference provided an opportunity to channel latent European hostilities towards one another outward; provide new areas for helping the European powers expand in the face of rising American, Russian and Japanese interests; and form constructive dialogue to limit future hostilities. In Africa, colonialism was introduced across nearly all the continent. When African independence was regained after World War II, it was in the form of fragmented states.

The Scramble for Africa sped up after the Conference since even within areas designated as their sphere of influence, the European powers had to take effective possession by the principle of effectivity. In central Africa in particular, expeditions were dispatched to coerce traditional rulers into signing treaties, using force if necessary, such as was the case for Msiri, King of Katanga, in 1891. Bedouin- and Berber-ruled states in the Sahara and the Sahel were overrun by the French in several wars by the beginning of

online

30 topical chapters by experts. * Hochschild, Adam (1999). ''

The Conference at Berlin on the West-African Question

. ''Political Science Quarterly'' 1(1). * Förster, Susanne, et al. "Negotiating German colonial heritage in Berlin's Afrikanisches Viertel." ''International Journal of Heritage Studies'' 22.7 (2016): 515–529. * Frankema, Ewout, Jeffrey G. Williamson, and P. J. Woltjer. "An economic rationale for the West African scramble? The commercial transition and the commodity price boom of 1835–1885." ''Journal of Economic History'' (2018): 231–267

online

* Harlow, Barbara, and Mia Carter, eds. ''Archives of Empire: Volume 2. The Scramble for Africa'' (Duke University Press, 2020). * Mulligan, William. "The Anti-slave Trade Campaign in Europe, 1888–90." in ''A Global History of Anti-slavery Politics in the Nineteenth Century'' (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2013). 149–17

online

* Nuzzo, Luigi (2012)

Colonial LawEGO – European History Online

Mainz

Institute of European History

Retrieved 25 March 2021

pdf

. * Rodney, Walter. ''

online

* Vanthemsche, Guy. ''Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980'' (Cambridge University Press, 2012). 289 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-19421-1 * Waller, Bruce. ''Bismarck at the crossroads: the reorientation of German foreign policy after the Congress of Berlin, 1878–1880'' (1974

online

* Yao, Joanne (2022). " The Power of Geographical Imaginaries in the European International Order: Colonialism, the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, and Model International Organizations". ''International Organization.''

Geography.about.com – Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 to Divide Africa

"The Berlin Conference"

BBC ''In Our Time''

General Act of the Berlin Conference

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

, to the other signatory powers.

* Definition of regions in which each European power had an exclusive right to pursue the legal ownership of land

The first reference in an international act to the obligations attaching to "spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

" is contained in the Berlin Act.

Principle of effective occupation

The principle of effective occupation stated that powers could acquire rights over colonial lands only if they possessed them or had "effective occupation": if they had treaties with local leaders, flew their flag there and established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force to keep order. The colonial power could also make use of the colony economically. That principle became important not only as a basis for the European powers to acquire territorialsovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

in Africa but also for determining the limits of their respective overseas possessions, as effective occupation served in some instances as a criterion for settling disputes over the boundaries between colonies. However, as the Berlin Act was limited in its scope to the lands that fronted on the African coast, European powers in numerous instances later claimed rights over lands in the interior without demonstrating the requirement of effective occupation, as articulated in Article 35 of the Final Act.

At the Berlin Conference, the scope of the Principle of Effective Occupation was heavily contested between Germany and France. The Germans, who were new to the continent, essentially believed that as far as the extension of power in Africa was concerned, no colonial power should have any legal right to a territory unless the state exercised strong and effective political control and, if so, only for a limited period of time, essentially an occupational force only. However, Britain's view was that Germany was a latecomer to the continent and was assumptively unlikely to gain any new possessions, apart from territories that were already occupied, which were swiftly proving to be more valuable than those occupied by Britain. That logic caused it to be generally assumed by Britain and France that Germany had an interest in embarrassing the other European powers on the continent and forcing them to give up their possessions if they could not muster a strong political presence. On the other side, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

had large territorial holdings there and wanted to keep them while it minimised its responsibilities and administrative costs. In the end, the British view prevailed.

The disinclination to rule what the Europeans had conquered is apparent throughout the protocols of the Berlin Conference but especially in the Principle of Effective Occupation. In line with Germany and Britain's opposing views, the powers finally agreed that it could be established by a European power establishing some kind of base on the coast from which it was free to expand into the interior. The Europeans did not believe that the rules of occupation demanded European hegemony on the ground. The Belgians originally wanted to include that "effective occupation" required provisions that "cause peace to be administered", but Britain and France were the powers that had that amendment struck out of the final document.

That principle, along with others that were written at the conference, allowed the Europeans to conquer Africa but to do as little as possible to administer or control it. The principle did not apply so much to the hinterlands of Africa at the time of the conference. This gave rise to "hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning "the land behind" (a city, a port, or similar). Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associated ...

theory", which basically gave any colonial power with coastal territory the right to claim political influence over an indefinite amount of inland territory. Since Africa was irregularly shaped, that theory caused problems and was later rejected.

Agenda

* Portugal–Britain: The Portuguese government presented a project, known as the " Pink Map", or the "Rose-Coloured Map", in which the colonies of Angola and Mozambique were united by co-option of the intervening territory (the land later becameZambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

, Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and ...

, and Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeas ...

). All of the countries attending the conference, except for Britain, endorsed Portugal's ambitions, and just over five years later, in 1890, the British government issued an ultimatum

An ultimatum (; ) is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance (open loop). An ultimatum is generally the final demand in a series ...

that demanded for the Portuguese to withdraw from the disputed area.

* France–Britain: A line running from Say

Say may refer to:

Music

*''Say'' (album), 2008 album by J-pop singer Misono

* "Say" (John Mayer song), 2007

*"Say (All I Need)", 2007 song by American pop rock band OneRepublic

* "Say" (Method Man song), 2006 single by rapper Method Man

* "Say" ( ...

in Niger to Maroua

Maroua (Fula: Marwa 𞤥𞤢𞤪𞤱𞤢) is the capital of the Far North Region of Cameroon, stretching along the banks of the Ferngo and Kaliao Rivers, in the foothills of the Mandara Mountains. The city had 301,371 inhabitants at the 2005 ...

, on the northeastern coast of Lake Chad, determined which part belonged to whom. France would own territory to the north of the line, and Britain would own territory to the south of it. The basin of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

would be British, with the French taking the basin of Lake Chad. Furthermore, between the 11th

11 (eleven) is the natural number following 10 and preceding 12. It is the first repdigit. In English, it is the smallest positive integer whose name has three syllables.

Name

"Eleven" derives from the Old English ', which is first atteste ...

and 15th degrees north in latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

, the border would pass between Ouaddaï, which would be French, and Darfur in Sudan, which would be British. In reality, a no man's land 200 km wide was put in place between the 21st and 23rd meridians east.

* France–Germany: The area to the north of a line, formed by the intersection of the 14th meridian east and Miltou, was designated to be French, and the area to the south would be German, later called German Cameroon

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

.

* Britain–Germany: The separation came in the form of a line passing through Yola, on the Benue, Dekoa

Dekoa (Dékoua) is a sub-prefecture and town in the Kémo Prefecture of the south-eastern Central African Republic.

History

In the nineteenth century freebooter Rabih az-Zubayr brought Dekoa under his sway and made it a part of the Bornu Empire. ...

, going up to the extremity of Lake Chad.

* France–Italy: Italy was to own what lies north of a line from the intersection of the Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, which is also referred to as the Northern Tropic, is the most northerly circle of latitude on Earth at which the Sun can be directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted tow ...

and the 17th meridian east to the intersection of the 15th parallel north

The 15th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 15 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Saharan fringe (the Sahel) in Africa, three key peninsulars of Asia (between which parts of the Indian Ocean), the Pacific ...

and the 21st meridian east

The meridian 21° east of Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, Europe, Africa, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole.

The 21st meridian e ...

.

Aftermath

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The British moved up from South Africa and down from Egypt and conquered states such as the Mahdist State

The Mahdist State, also known as Mahdist Sudan or the Sudanese Mahdiyya, was a state based on a religious and political movement launched in 1881 by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah (later Muhammad al-Mahdi) against the Khedivate of Egypt, which had ...

and the Sultanate of Zanzibar

The Sultanate of Zanzibar ( sw, Usultani wa Zanzibar, ar, سلطنة زنجبار , translit=Sulṭanat Zanjībār), also known as the Zanzibar Sultanate, was a state controlled by the Sultan of Zanzibar, in place between 1856 and 1964. The Su ...

and, having already defeated the Zulu Kingdom in South Africa in 1879, moved on to subdue and dismantle the independent Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

republics of Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

.

Within a few years, Africa was at least nominally divided up south of the Sahara. By 1895, the only independent states were:

* , involved in colonial conflicts with Spain and France, which conquered the nation in the early 20th century.

* , founded with the support of the United States for freed slaves to return to Africa.

* , which fended off Italian invasion from Eritrea in the First Italo-Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, lit. ''Abyssinian War'' was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disputed Treaty of Wuchale, which the Italians claimed turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. Full-sc ...

of 1895–1896 but fell to Italian colonialism in 1936 defeat during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

*

Majeerteen Sultanate

The Majeerteen Sultanate ( so, Suldanadda Majeerteen 𐒈𐒚𐒐𐒆𐒖𐒒𐒖𐒆𐒆𐒖 𐒑𐒖𐒃𐒜𐒇𐒂𐒜𐒒, lit=Boqortooyada Majerteen, ar, سلطنة مجرتين), also known as Majeerteen Kingdom or Majeerteenia and Migiu ...

, founded in the early 18th century, it was annexed by Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

in the 20th century.

*

Sultanate of Hobyo

The Sultanate of Hobyo ( so, Saldanadda Hobyo, ar, سلطنة هوبيو), also known as the Sultanate of Obbia,''New International Encyclopedia'', Volume 21, (Dodd, Mead: 1916), p.283. was a 19th-century Somali kingdom in present-day northeaste ...

, carved out of the former Majeerteen Sultanate, which ruled northern Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

until the 20th century, when it was incorporated by Italy.

The following states lost their independence to the British Empire roughly a decade after (see below for more information):

* , a Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

republic founded by Dutch settlers, an entirely white-dominated state

* (Transvaal), also a Boer republic

By 1902, 90% of all the land that makes up Africa was under European control. Most of the Sahara was French, but after the quelling of the Mahdi rebellion and the ending of the Fashoda crisis, the Sudan remained firmly under joint British–Egyptian rulership, with Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

being under British occupation before becoming a British protectorate in 1914.

The Boer republics were conquered by the British in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

from 1899 to 1902. Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

was conquered by Italy in 1911, and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

was divided between the French and Spanish in 1912.

Motives and David Livingstone's Crusade

One of the chief stated justifications "was a desire to stamp out slavery once and for all". Before his death in 1873, Christian missionary, David Livingstone, called for a ''worldwide'' crusade to defeat the Arab-controlled slave trade in East Africa. The way to do it was to "liberate Africa" by introduction of "commerce, Christianity" and civilization. Crowe, Craven and Katzenellenbogen are authors who have attempted to soften the language and therefore the intent of the conference. They warn against an overemphasis of its role in the colonial partitioning of Africa, extensively justifying it by ignoring the motivations and outcomes of the conference by only drawing attention to bilateral agreements concluded before and after the conference, regardless of whether they were finalized and followed in practice. For example, Craven has questioned the legal and economic impact of the conference. However, the countries that ultimately participated in the Final Act ignored requirements set forth within it to establish their satellite governments, rights to the land and trade in the benefit of their national, domestic economies.Analysis by historians

Historians have long marked the Berlin Conference as the formalisation of the Scramble for Africa but recently, scholars have questioned the legal and economic impact of the conference. Some have argued the conference central to imperialism.African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

historian W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in 1948 that alongside the Atlantic slave trade in Africans a great world movement of modern times is "the partitioning of Africa after the Franco-Prussian War which, with the Berlin Conference of 1884, brought colonial imperialism to flower" and that " e primary reality of imperialism in Africa today is economic," going on to expound on the extraction of wealth from the continent.

Other historians focus on the legal implications in international law and argue that the conference was only one of many (mostly bilateral) agreements between prospective colonists, which took place after the conference.

See also

* Brussels Conference Act of 1890 *Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation

European colonialism and colonization was the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over other societies and territories, founding a colony, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically. For example, colo ...

References

Sources

* Chamberlain, Muriel E. (2014). ''The Scramble for Africa''. London: Longman, 1974, 4th edn. . *Craven, M. 2015. "Between law and history: the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 and the logic of free trade." '' London Review of International Law'' 3, 31–59. * Crowe, Sybil E. (1942). ''The Berlin West African Conference, 1884–1885''. New York: Longmans, Green. (1981, New ed. edition). * Förster, Stig, Wolfgang Justin Mommsen, and Ronald Edward Robinson, eds. ''Bismarck, Europe and Africa: The Berlin Africa conference 1884–1885 and the onset of partition'' (Oxford University Press, 1988online

30 topical chapters by experts. * Hochschild, Adam (1999). ''

King Leopold's Ghost

''King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa'' (1998) is a best-selling popular history book by Adam Hochschild that explores the exploitation of the Congo Free State by King Leopold II of Belgium between 1885 ...

''. .

*Katzenellenbogen, S. 1996. It didn't happen at Berlin: Politics, economics and ignorance in the setting of Africa's colonial boundaries. In Nugent, P. and Asiwaju, A. I. (Eds.), ''African boundaries: Barriers, conduits and opportunities''. pp. 21–34. London: Pinter.

* Petringa, Maria (2006). ''Brazza, A Life for Africa''. .

* Lorin, Amaury, and de Gemeaux, Christine, eds., ''L'Europe coloniale et le grand tournant de la Conférence de Berlin (1884–1885)'', Paris, Le Manuscrit, coll. "Carrefours d'empires", 2013, 380 p.

Further reading

* Craven, Matthew. ''The invention of a tradition: Westlake, the Berlin Conference and the historicisation of international law'' (Klosterman, 2012). * Leon, Daniel De (1886).The Conference at Berlin on the West-African Question

. ''Political Science Quarterly'' 1(1). * Förster, Susanne, et al. "Negotiating German colonial heritage in Berlin's Afrikanisches Viertel." ''International Journal of Heritage Studies'' 22.7 (2016): 515–529. * Frankema, Ewout, Jeffrey G. Williamson, and P. J. Woltjer. "An economic rationale for the West African scramble? The commercial transition and the commodity price boom of 1835–1885." ''Journal of Economic History'' (2018): 231–267

online

* Harlow, Barbara, and Mia Carter, eds. ''Archives of Empire: Volume 2. The Scramble for Africa'' (Duke University Press, 2020). * Mulligan, William. "The Anti-slave Trade Campaign in Europe, 1888–90." in ''A Global History of Anti-slavery Politics in the Nineteenth Century'' (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2013). 149–17

online

* Nuzzo, Luigi (2012)

Colonial Law

Mainz

Institute of European History

Retrieved 25 March 2021

. * Rodney, Walter. ''

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

''How Europe Underdeveloped Africa'' is a 1972 book written by Walter Rodney that describes how Africa was deliberately exploited and underdeveloped by European colonial regimes. One of his main arguments throughout the book is that Africa develop ...

'' (1972) –

* Shepperson, George. "The Centennial of the West African Conference of Berlin, 1884–1885." ''Phylon'' 46#1 (1985), pp. 37–48online

* Vanthemsche, Guy. ''Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980'' (Cambridge University Press, 2012). 289 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-19421-1 * Waller, Bruce. ''Bismarck at the crossroads: the reorientation of German foreign policy after the Congress of Berlin, 1878–1880'' (1974

online

* Yao, Joanne (2022). " The Power of Geographical Imaginaries in the European International Order: Colonialism, the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, and Model International Organizations". ''International Organization.''

External links

Geography.about.com – Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 to Divide Africa

"The Berlin Conference"

BBC ''In Our Time''

General Act of the Berlin Conference

South African History Online

The South African History Project (2001-2004) was established and initiated by Professor Kader Asmal, former Minister of Education in South Africa. This initiative followed after the publication of the Manifesto on Values, Education and Democra ...

.

{{Authority control

European colonisation in Africa

1884 in Germany

1885 in Germany

Diplomatic conferences in Germany

19th-century diplomatic conferences

1884 in international relations

1885 in international relations

1884 conferences

1885 conferences

1885 in Africa

1884 in Africa

19th century in Berlin

1880s in Prussia