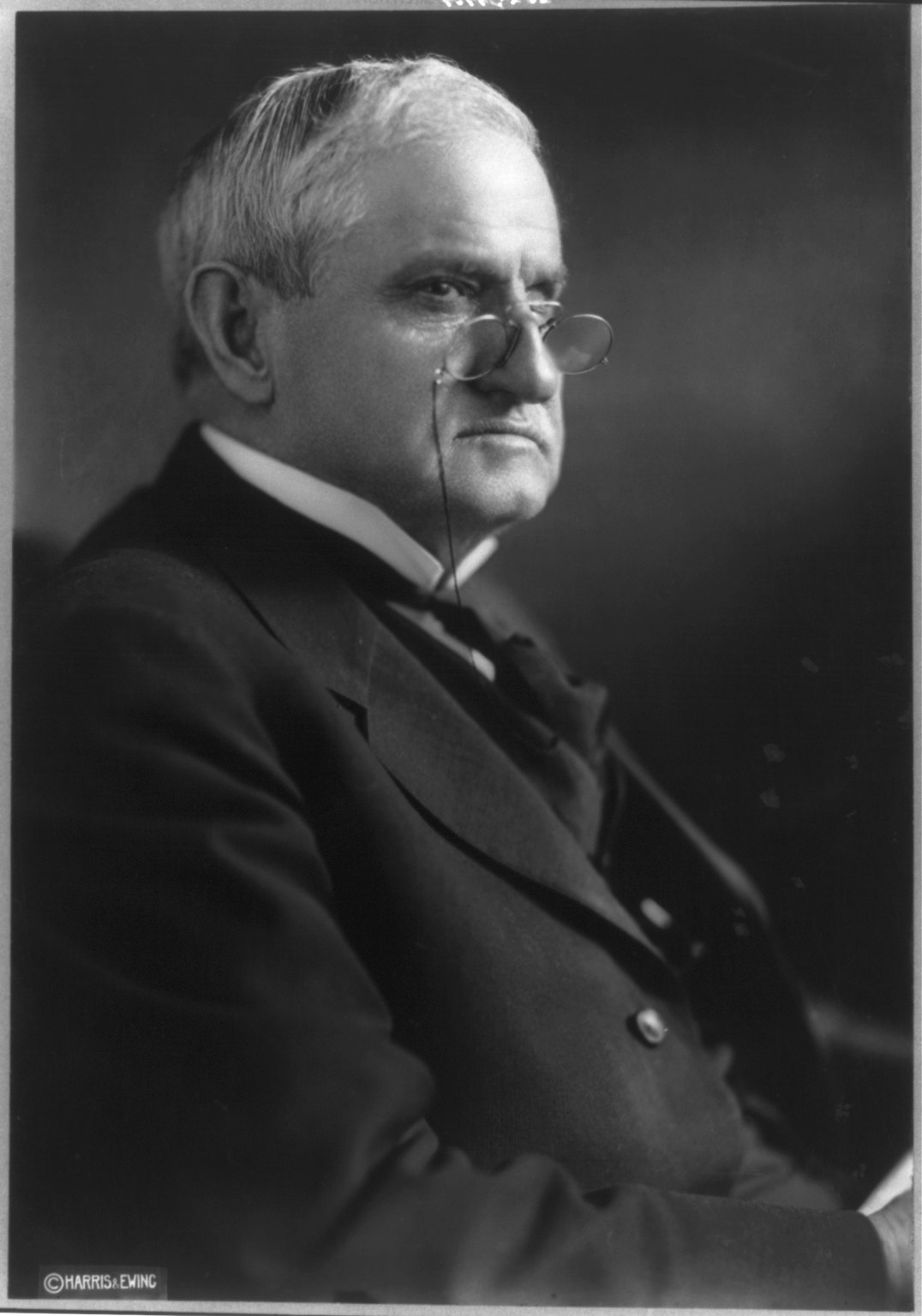

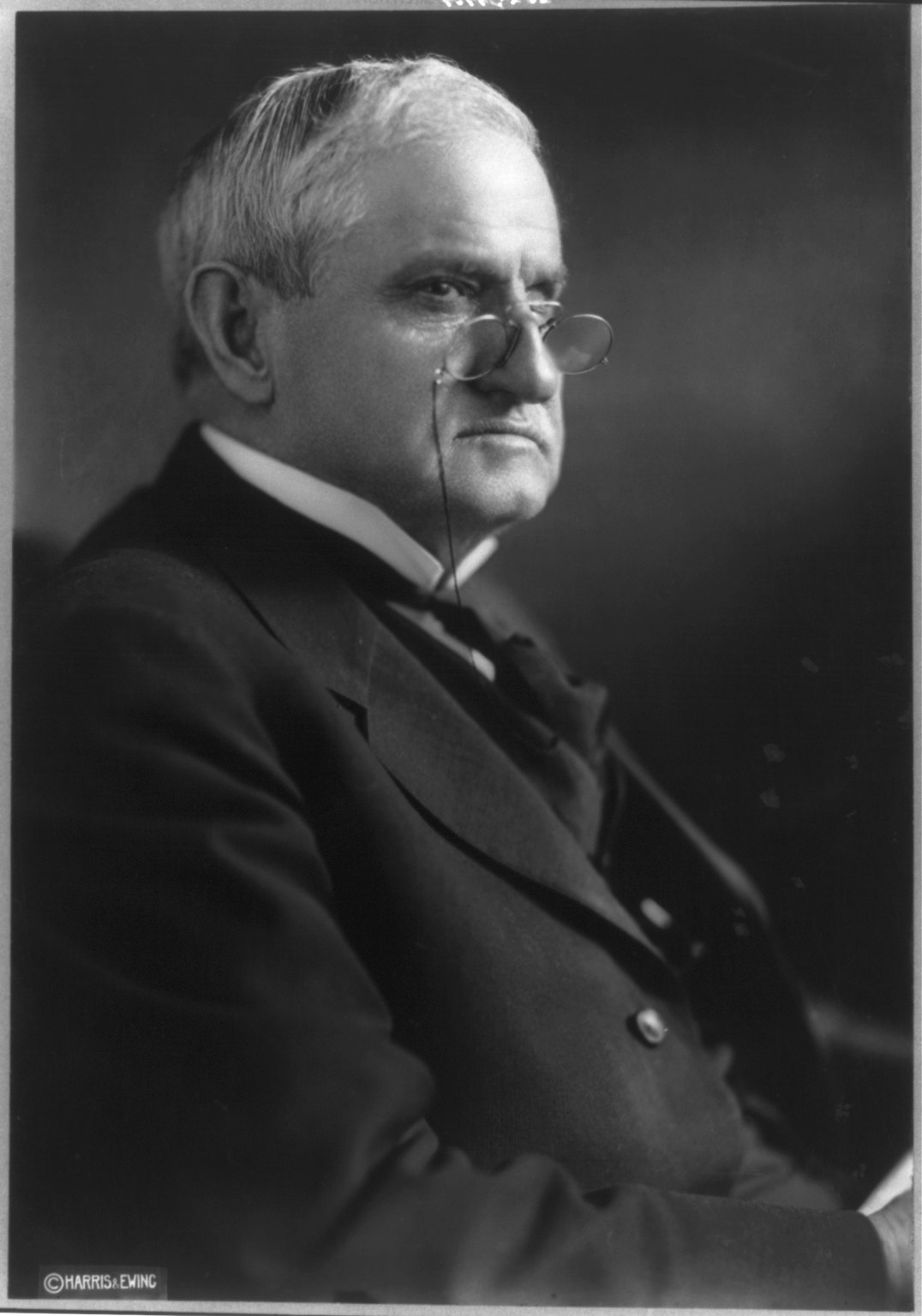

Benjamin Ryan Tillman (August 11, 1847 – July 3, 1918) was an American politician of the

Democratic Party who served as

governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a

United States Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from 1895 until his death in 1918. A

white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

who opposed

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

for

black Americans, Tillman led a paramilitary group of

Red Shirts during

South Carolina's violent 1876 election. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, he defended

lynching, and frequently ridiculed black Americans in his speeches, boasting of having helped kill them during that campaign.

In the 1880s, Tillman, a wealthy landowner, became dissatisfied with the Democratic leadership and led a movement of white farmers calling for reform. He was initially unsuccessful, though he was instrumental in the founding of

Clemson University

Clemson University () is a public land-grant research university in Clemson, South Carolina. Founded in 1889, Clemson is the second-largest university in the student population in South Carolina. For the fall 2019 semester, the university enr ...

as an agricultural

land-grant college

A land-grant university (also called land-grant college or land-grant institution) is an institution of higher education in the United States designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890.

Signed by Abraha ...

. In 1890, Tillman took control of the state Democratic Party, and was elected governor. During his four years in office, 18 black Americans were

lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

in South Carolina; in the 1890s, the state had its highest number of lynchings of any decade. Tillman tried to prevent lynchings as governor but also spoke in support of the lynch mobs, alleging his own willingness to lead one. In 1894, at the end of his second two-year term, he was elected to the U.S. Senate by vote of the state legislature, who elected senators at the time.

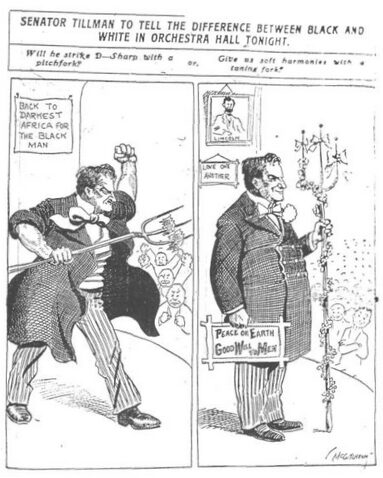

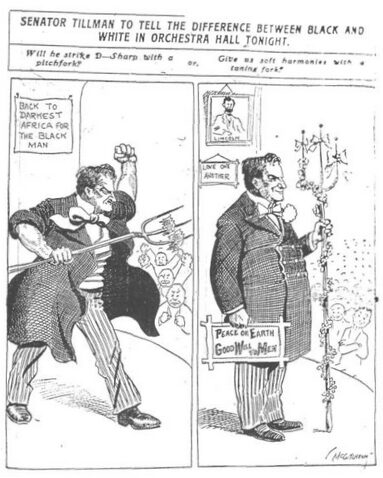

Tillman was known as "Pitchfork Ben" because of his aggressive language, as when he threatened to use a

pitchfork

A pitchfork (also a hay fork) is an agricultural tool with a long handle and two to five tines used to lift and pitch or throw loose material, such as hay, straw, manure, or leaves.

The term is also applied colloquially, but inaccurately, to ...

to prod that "bag of beef", President

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

. Considered a possible candidate for the Democratic nomination for president in

1896

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The Jameson Raid comes to an end, as Jameson surrenders to the Boers.

* January 4 – Utah is admitted as the 45th U.S. state.

* January 5 – An Austrian newspaper reports that ...

, Tillman lost any chance after giving a disastrous speech at

the convention. He became known for his virulent oratoryespecially against black Americansbut also for his effectiveness as a legislator. The first federal

campaign finance

Campaign finance, also known as election finance or political donations, refers to the funds raised to promote candidates, political parties, or policy initiatives and referendums. Political parties, charitable organizations, and political a ...

law, banning corporate contributions, is commonly called the

Tillman Act

The Tillman Act of 1907 (34 Stat. 864) was the first campaign finance law in the United States. The Act prohibited monetary contributions to federal candidates by corporations and nationally chartered (interstate) banks.

The Act was signed int ...

. Tillman was repeatedly re-elected, serving in the Senate for the rest of his life. One of his legacies was

South Carolina's 1895 constitution, which

disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

most of the black majority and many poor whites, and ensured white Democratic Party rule for more than six decades into the 20th century.

Early life and education

Benjamin Ryan Tillman Jr. was born on August 11, 1847, on the family plantation "Chester", near

Trenton, in the Edgefield District, sometimes considered part of

upcountry South Carolina. His parents, Benjamin Ryan Tillman Sr. and the former Sophia Hancock, were of English descent.

In addition to being planters with 86 slaves, the Tillmans operated an inn. They owned 2500 acres of land and were among the largest slaveholders in the district. Benjamin Jr. was the last-born of seven sons and four daughters.

The Edgefield District was known as a violent place, even by the standards of

antebellum South Carolina

Antebellum South Carolina is typically defined by historians as South Carolina during the period between the War of 1812, which ended in 1815, and the American Civil War, which began in 1861.

After the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, the ec ...

, where matters of personal honor might be addressed with a killing or duel. Before Tillman Sr.'s death from

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

in 1849, he had killed a man and been convicted of rioting by an Edgefield jury. One of his sons died in a duel; another was killed in a domestic dispute. A third died in the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

; a fourth at the age of 15 from disease.

Of Benjamin Jr.'s two surviving brothers, one died of

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

wounds after returning home, and the other,

George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

, killed a man who accused him of cheating at gambling. Convicted of manslaughter, George continued to practice law from his jail cell during his two-year sentence, and was elected to the

state senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

while still incarcerated. He later served several terms in Congress.

From an early age, Ben showed a developed vocabulary. In 1860, he was sent to Bethany, a boarding school in Edgefield where he became a star student, and he remained there after the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

began. In 1863, he came home for a year to help his mother pay off debts. He returned to Bethany in 1864, intending a final year of study prior to entering the South Carolina College (today, the

University of South Carolina). The South's desperate need for soldiers ended this plan. In June 1864, not yet 17, Tillman withdrew from the academy, making arrangements to join a

coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

unit. These plans were scuttled as well when he fell ill at home. A cranial tumor required the removal of his left eye. It was not until 1866, months after Confederate forces had disbanded, that Ben Tillman was again healthy.

After the war, Ben Tillman, his mother, and his wounded brother James (who died in 1866) worked to rebuild Chester plantation. They signed the plantation's

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

as workers. They were confronted with the circumstance of several men refusing to work for them and legally leaving the plantation. From 1866 to 1868, Ben Tillman went with several workers from the plantation to Florida, where a new cotton cultivation belt had been established. The Tillmans purchased land there. Tillman was unsuccessful in Florida: after two marginal years, the 1868 crop was destroyed by caterpillars.

During his convalescence, Tillman had met Sallie Starke, a refugee from

Fairfield District. They married in January 1868

and she joined him in Florida. The Tillmans returned to South Carolina, where the following year they settled on of Tillman family land, given to him by his mother.

They would have seven children together: Adeline, Benjamin Ryan, Henry Cummings, Margaret Malona, Sophia Oliver, Samuel Starke, and Sallie Mae.

Though he was not very religious, Tillman was a frequent churchgoer as a young adult. He was a Christian, but did not identify with a particular sect; as a result, he never formally joined a church. His religious skepticism also led to his avoidance of any further churchgoing almost immediately following his becoming a politician.

Tillman proved an adept farmer, who experimented with

crop diversification and took his crops to market each Saturday in nearby

Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Georgi ...

. In 1878, Tillman inherited from Sophia Tillman, and purchased at

Ninety Six, some from his Edgefield holdings. Having inherited a large library from his uncle John Tillman, he spent part of his days reading.

Although his workers were no longer slaves, Tillman continued to apply the whip to them. By 1876, Tillman was the largest landowner in Edgefield County. He rode through his fields on horseback like an antebellum

overseer, and stated at the time that it was necessary that he do so to "drive the slovenly Negroes to work".

Red Shirts and Reconstruction

Resistance to Republican rule

With the Confederacy defeated, South Carolina ratified a new constitution in 1865 that recognized the end of slavery, but basically left the pre-war elites in charge. African-American freedmen, who were the majority of South Carolina's population, were given no vote, and their new freedom was soon restricted by

Black Codes that limited their civil rights and required black farm laborers to bind themselves with annual labor contracts. Congress was dissatisfied with this minimal change and required a new constitutional convention and elections with universal male suffrage. As African Americans generally favored the Republican Party at the time, their votes resulted in that party controlling the biracial state legislature beginning with the 1868 elections. That campaign was marked by violence; 19 Republican and

Union League

The Union Leagues were quasi-secretive men’s clubs established separately, starting in 1862, and continuing throughout the Civil War (1861–1865). The oldest Union League of America council member, an organization originally called "The Leag ...

activists were killed in

South Carolina's 3rd congressional district

The 3rd congressional district of South Carolina is a congressional district in western South Carolina bordering both Georgia and North Carolina. It includes all of Abbeville, Anderson, Edgefield, Greenwood, Laurens, McCormick, Oconee, P ...

alone.

In 1873, two Edgefield lawyers and former Confederate generals,

Martin Gary and

Matthew C. Butler, began to advocate what became known as the "Edgefield Plan" or "Straightout Plan". They believed that the previous five years had shown it was not possible to outvote African Americans. Gary and Butler deemed compromises with black leaders to be misguided; they believed that white men must be restored to their antebellum position of preeminent political power in the state. They proposed that white men form clandestine paramilitary organizations—known as "rifle clubs"—and use force and intimidation to drive African Americans from power. Members of the new white groups became known as

Red Shirts. Tillman was an early and enthusiastic recruit for his local organization, dubbed the Sweetwater Sabre Club.

He became a devoted protégé of Gary.

From 1873 to 1876, Tillman served as a member of the Sweetwater club, members of which assaulted and intimidated black would-be voters, killed black political figures, and skirmished with the African-American-dominated state militia.

Economic coercion was used as well as physical force: most Edgefield planters would not employ black militiamen or allow them to rent land, and ostracized whites who did.

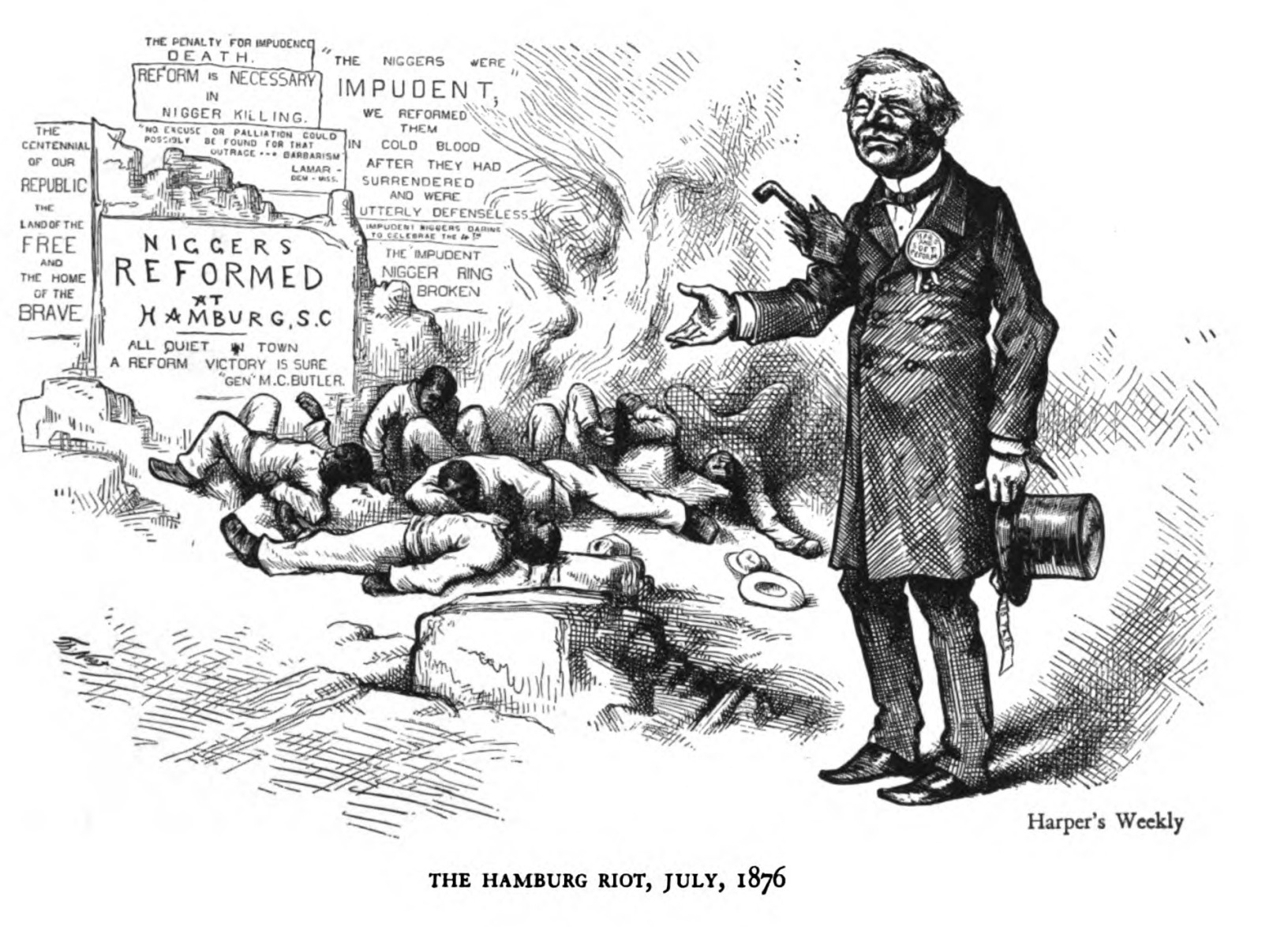

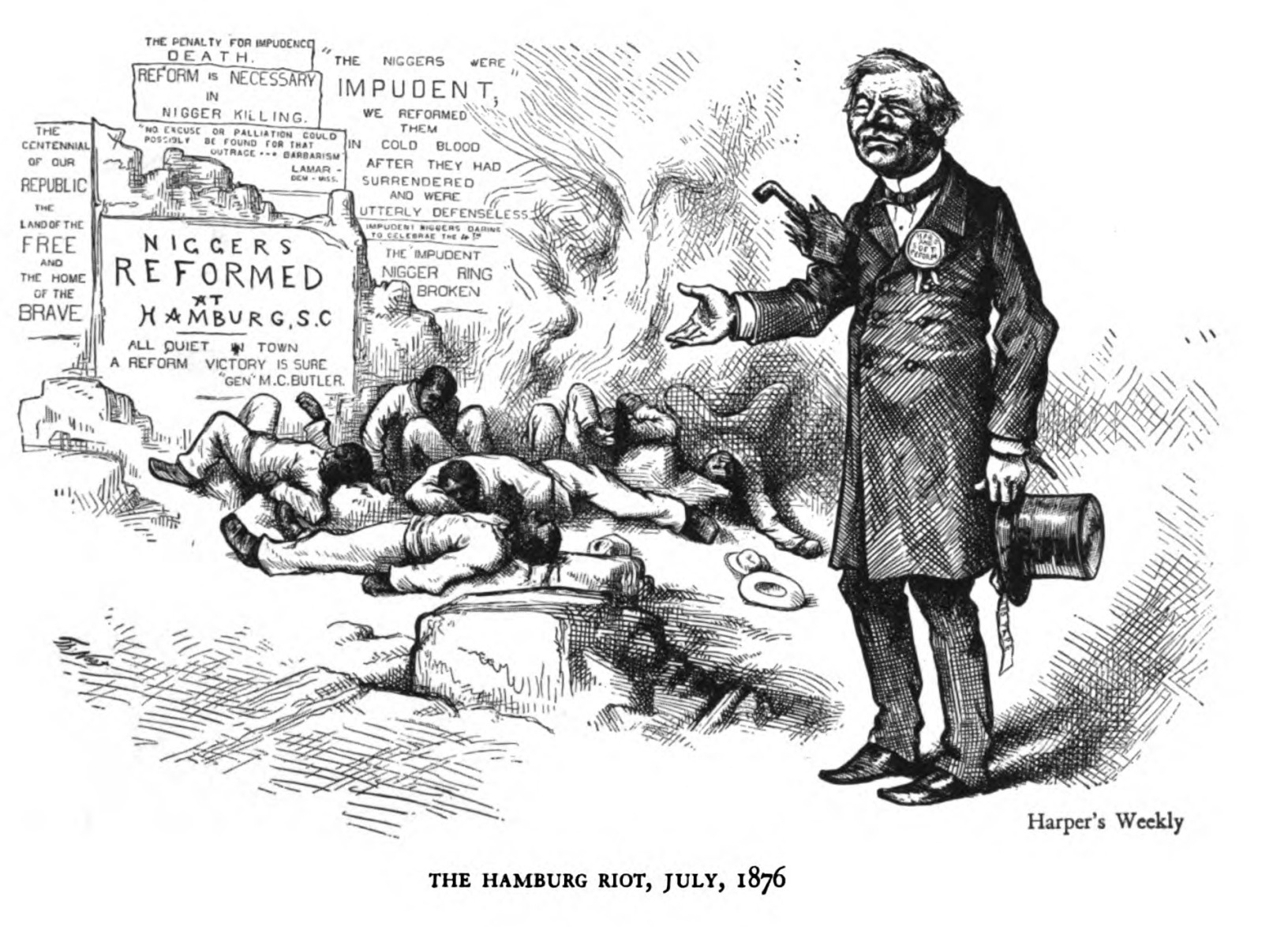

Hamburg massacre; campaign of 1876

In 1874, a moderate Republican,

Daniel Henry Chamberlain, was elected South Carolina's governor, attracting even some Democratic votes. When Chamberlain sought re-election in 1876, Gary recruited

Wade Hampton III, a Confederate war hero who had moved out of state, to return and run for governor as a Democrat.

That election

campaign of 1876 was marked by violence, of which the most notorious occurrence was what became known as the

Hamburg massacre

The Hamburg Massacre (or Red Shirt Massacre or Hamburg riot) was a riot in the American town of Hamburg, South Carolina, in July 1876, leading up to the last election season of the Reconstruction Era. It was the first of a series of civil dis ...

. It occurred in

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, a mostly black town across the

Savannah River from Augusta, in

Aiken County, bordering Edgefield County. The incident grew out of a confrontation on July 4 when a black militia marched in Hamburg and two white farmers in a buggy tried to ride through its ranks. Both sides filed criminal charges against the other, and dozens of armed out-of-uniform Red Shirts, led by Butler, traveled to Hamburg on the day of the hearing, July 8. Tillman was present, and the subsequent events were among his proudest memories.

The hearing never occurred, as the black militiamen, outnumbered and outgunned, refused to attend court. This upset the white mob, which expected an apology. Butler demanded that the militiamen give one, and as part of the apology, surrender their arms. Those who attempted to mediate found that neither Butler nor the armed men who backed him were interested in compromise. If the militiamen surrendered their arms, they would be helpless before the mob; if they did not, Butler and his men would use force. Butler brought additional men in from Georgia, and the augmented armed mob, including Tillman, went to confront the militiamen, who were barricaded in their drill room, above a local store. Shots were fired, and after one white man was killed, the rest stormed the room and captured about thirty of the militia. Five were murdered as having white enemies; among the dead was a town constable who had arrested white men. The rest were allowed to flee, with shots fired after them. At least seven black militiamen were killed in the incident. On the way home to Edgefield, Tillman and others had a meal to celebrate the events at the home of the man who had pointed out which African Americans should be shot.

Tillman later recalled that "the leading white men of Edgefield" had decided "to seize the first opportunity that the Negroes might offer them to provoke a riot and teach the Negroes a lesson" by "having the whites demonstrate their superiority by killing as many of them as was justifiable".

Hamburg was their first such opportunity. Ninety-four white men, including Tillman, were indicted by a coroner's jury, but none was prosecuted for the killings. Butler blamed the deaths on intoxicated factory workers and Irish-Americans who had come across the bridge from Augusta, and over whom he had no control.

Tillman raised his profile in state politics by attending the 1876 state Democratic convention, which nominated Hampton as the party's candidate for governor. While Hampton presented a fatherly image, urging support from South Carolinians, black and white, Tillman led fifty men to

Ellenton, intending to join more than one thousand rifle club members who

slaughtered thirty militiamen, with the survivors saved only by the arrival of federal authorities. Although Tillman and his men arrived too late to participate in those killings, two of his men murdered Simon Coker, a black state senator who had come to investigate reports of violence. They shot him as he knelt in final prayer.

On Election Day in November 1876, Tillman served as an election official at a local poll, as did two black Republicans. One arrived late and was scared off by Tillman. As there was as yet no secret ballot in South Carolina, Tillman threatened to remember any votes cast for the Republicans. That precinct gave 211 votes for the Democrats and 2 for the Republicans. Although almost two-thirds of those eligible to vote in Edgefield were African Americans, the Democrats were able to suppress the (Republican) African-American vote, reporting a win for Hampton in Edgefield County with over 60 percent of the vote. Bolstered by this result, Hampton gained a narrow victory statewide, at least according to the official returns. The Red Shirts used violence and fraud to create Democratic majorities that did not exist, and give Hampton the election.

Tillman biographer Stephen Kantrowitz wrote that the unrest in 1876 "marked a turning point in Ben Tillman's life, establishing him as a member of the political and military leadership". Historian

Orville Vernon Burton stated that the violence "secured his prominence among the state's white political elite and proved to be the deathblow to South Carolina's Republican Reconstruction government."

The takeover, by fraud and terror, of South Carolina's government became known to whites as the state's "

Redemption".

In 1909, Tillman addressed a reunion of Red Shirts in

Anderson, South Carolina

Anderson is a city in and the county seat of Anderson County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 28,106 at the 2020 census, and the city was the center of an urbanized area of 75,702. It is one of the principal cities in the Green ...

, and recounted the events of 1876:

"Agricultural Moses"

Starting with the election of Hampton as governor in 1876, South Carolina was ruled primarily by the wealthy "

Bourbon" or "Conservative" planter class that had controlled the state before the Civil War. In the 1880s, though, the Bourbon class was neither as strong nor as populous as before. The agenda of the Conservatives had little to offer the farmer, and in the hard economic times of the early 1880s, there was discontent in South Carolina that led to some electoral success for the short-lived

Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

.

Having risen to the rank of captain in the rifle club before the end of the 1876 campaign, Tillman spent the next several years managing his plantations. He played a modest role in Edgefield's political and social life, and in 1881 was elected second in command of the Edgefield Hussars, a rifle club that had been made part of the state militia. He supported Gary's unsuccessful candidacy for the Democratic nomination for governor in 1880, and after Gary's death in 1881,

as a delegate to the 1882 Democratic state convention Tillman backed former Confederate general

John Bratton

John Bratton (March 7, 1831 – January 12, 1898) was a U.S. Representative from South Carolina, as well as a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He rose from private to brigadier general and led a regimen ...

for the nomination, again unsuccessfully. By then, Tillman was dissatisfied with the Conservative leaders he had helped gain power; he believed they were ignoring the interests of farmers and of poor mill workers, and had been responsible for denying office to Gary

—the former Red Shirt leader had twice sought to be senator, and once governor, and was each time denied.

Tillman never forgot what he deemed the "betrayal" of Gary.

Struggle for the farmer

In an attempt to better conditions for the farmer (by which Tillman always meant white males only), in 1884 he founded the Edgefield Agricultural Club. It died for lack of members. Undeterred, Tillman tried again in January 1885, beginning the Edgefield County Agricultural Society. Its membership also dwindled, but Tillman was elected one of three delegates to the August joint meeting of the state

Grange and the state Agricultural and Mechanical Society at

Bennettsville, and was invited to be one of the speakers.

When Tillman spoke at Bennettsville, he was not widely known except as the brother of Congressman George Tillman. Ben Tillman called for the state government to do more for farmers, and blamed politicians and lawyers in the pay of financial interests for agricultural problems, including the

crop lien system that left many farmers struggling to pay bills. He assailed his listeners for letting themselves be duped by hostile interests, and told of the farmer who was elected to the legislature, only to be dazzled and seduced by the elite. According to an account the next day in the ''Columbia Daily Register'', Tillman's speech "electrified the assembly and was the sensation of the meeting". Lindsey Perkins, in his journal article on Tillman's oratory, wrote that "Tillman's losses in the agricultural depression of 1883–1898 forced him to begin thinking and planning economic reforms. The result was Bennettsville." Tillman later stated that he began his advocacy after a few bad years in the early 1880s forced him to sell some of his land. The speech was printed in several newspapers, and Tillman began to receive more invitations to speak. According to Zach McGhee in his 1906 article on Tillman, "from that day to this he has been the most conspicuous figure in South Carolina".

Within two months of the Bennettsville speech, Tillman was being talked of as a candidate for governor in 1886. He continued to speak to audiences, and was dubbed the "Agricultural Moses". He made political demands, such as primary elections to determine who would get the Democratic nomination (then

tantamount to election

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinati ...

) rather than the leaving the decision to the Bourbon-dominated state nominating convention. He principally promoted the establishment of a state college for the education of farmers, where young men could learn the latest techniques. Kantrowitz pointed out that the term "farmer" is flexible in meaning, allowing Tillman to overlook distinctions of class and unite most white men in predominantly rural South Carolina under a single banner. During these years, cartoonists began depicting Tillman with pitchfork in hand, symbolizing his agriculture-based roots and tendency to take jabs at opponents. This was a source of his nickname, "Pitchfork Ben".

Historian H. Wayne Morgan noted that "Ben Tillman's venom was not typical, but his general feeling represented that of southern dirt farmers." According to E. Culpepper Clark in his journal article on Tillman,

Tillman spoke widely in the state in 1885 and after, and soon attracted allies, including a number of Red Shirt comrades, such as Martin Gary's nephews

Eugene B. Gary and

John Gary Evans

John Gary Evans (October 15, 1863June 26, 1942) was the 85th governor of South Carolina from 1894 to 1897.

Early life

Evans was born in Cokesbury, South Carolina to an aristocratic and well-connected family. His father was Nathan George E ...

. He sought to mold local farmers' groups into a statewide organization to be a voice for agriculturalists. In April 1886, a convention called by Tillman met in

Columbia, the state capital. The goal of what became known as the Farmer's Association or Farmer's Movement was to control the state Democratic Party from within, and to gain reforms such as the agricultural college. He initially was unsuccessful, though he came within thirty votes of controlling the 1886 state Democratic convention. The lack of success caused Tillman, in late 1887, to announce his retirement from politics, though there was widespread speculation he would soon be back.

Tillman had met, in 1886, with

Thomas G. Clemson, son-in-law of the late

John C. Calhoun, to discuss a bequest to underwrite the cost of the new agricultural school. Clemson died in 1888, and his will not only left money and land for the college, but made Tillman one of seven trustees for life, who had the power to appoint their successors. Tillman stated that this provision, which made the lifetime trustees a majority of the board, was intended to forestall any attempt by a future Republican government to admit African Americans. Clemson College (later

Clemson University

Clemson University () is a public land-grant research university in Clemson, South Carolina. Founded in 1889, Clemson is the second-largest university in the student population in South Carolina. For the fall 2019 semester, the university enr ...

) was authorized by the legislature in December 1888.

The Clemson bequest helped revitalize Tillman's movement. The targets of Tillman's oratory were again politicians in Columbia and the Conservative elements based in

Charleston and elsewhere in the

lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

of South Carolina. Through letters to newspapers and stump speeches, he decried the state government as a pit of corruption,

stating that officials displayed "ignorance, extravagance and laziness" and that Charleston's

The Citadel

The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina, commonly known simply as The Citadel, is a public senior military college in Charleston, South Carolina. Established in 1842, it is one of six senior military colleges in the United States. ...

was a "military dude factory" that might profitably be repurposed as a school for women.

Governor

John P. Richardson had been elected in 1886; in 1888 he sought re-nomination, to be met with opposition from Tillman's farmers. As had been done to Republican rallies in 1876, Tillman and his followers attended campaign events and demanded that he be allowed equal time to speak. Tillman was a highly talented stump speaker, and when given the opportunity to debate, accused Richardson of being irreligious, a gambler and a drunkard. Even so, Richardson was easily re-nominated by the state Democratic convention, which turned down Tillman's demand for a primary election. Tillman proposed the customary gracious motion that Richardson's nomination be made unanimous.

1890 gubernatorial campaign

One factor that helped Tillman and his movement in the 1890 campaign was the organization of many South Carolina farmers under the auspices of the

Farmers' Alliance

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and ...

. The Alliance, which had spread through much of the agricultural South and West since its origin in Texas, sought to get farmers to work together cooperatively and seek reform. From that organization would come the

People's Party (better known as the Populists). Although the Populist Party played a significant role in the politics of the 1890s, it did not do so in South Carolina, where Tillman had already channeled agricultural discontent into an attempt to take over the Democratic Party. The Alliance in South Carolina generally backed Tillman, and its many local farmers' organizations gave Tillman new venues for his speeches.

In January 1890, Tillmanite leader

George Washington Shell published what came to be known as the "Shell Manifesto" in a Charleston newspaper, setting forth the woes of farmers under the Conservative government, and calling for them to elect delegates to meet in March to recommend a candidate for governor. Both Tillman supporters and Conservatives realized the purpose was to pre-empt the Democratic convention's choice, and fresh, acrimonious debate over the merits of Tillman and his methods began. He and his supporters were often attacked in the newspapers by the Conservatives, but such invective by the hated elites only tended to endear Tillman the more to the farmers who saw him as their champion. Conservatives were certain that once Tillman's voters understood how wealthy he was while speaking for debt-ridden farmers, they would abandon him; they did not.

At the "Shell Convention", state Representative

John L. M. Irby nominated Tillman, stating "shame on the

emocraticparty for stabbing Gary, a man who had saved us in '76 ... we could now make the amends honorable and choose B. R. Tillman". Although many delegates voted to make no endorsement, Tillman gained a narrow victory for the convention's recommendation. Tillman spent the summer of 1890 making speeches and debating two rivals (former general Bratton and

state Attorney General

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the federal district, or of any of the territories is the chief legal advisor to the state government and the state's chief law enforcement officer. In some states, the attorney gener ...

Joseph H. Earle

Joseph Haynsworth Earle (April 30, 1847May 20, 1897) was a United States Senator from South Carolina.

Biography

Born in Greenville, he attended private schools in Sumter. He was a first year cadet at the South Carolina Military Academy (now T ...

) for the nomination, as the Democratic leadership watched with increasing consternation. Given Tillman's strength at the

grassroots level, he was likely to be the choice of the Democratic convention in September. Accordingly, the party's Bourbon-controlled state executive committee tried to use the brief August convention (called to set the rules for the September one) to change the nomination method to a primary, in which the anti-Tillman forces would unite behind a single candidate. When the August convention was held, the Tillmanites had a large majority, which they used to oust the executive committee and install one loyal to Tillman. The convention also passed a new party constitution calling for a primary, beginning in 1892. Tillman was duly nominated in September as the Democratic candidate for governor, with Eugene Gary as his running mate for lieutenant governor.

After the convention many Conservative Democrats, though not happy at Tillman's victory, acknowledged him as head of the state party. Those who submitted to Tillman's rule included Hampton and Butler, the state's two U.S. senators. In his campaign, Tillman promoted support for Clemson, establishment of a state women's college, reapportionment of the state legislature (then dominated by the lowcountry counties), and ending the influence of corporation lawyers in that body.

Those Democrats who could not abide Tillman's candidacy held an October meeting with 20 of South Carolina's 35 counties represented, and nominated

Alexander Haskell for governor. The announcement that Haskell would run caused a closing of Democratic ranks against him, lest white unity be sundered. The ''

Charleston News and Courier'', not always a friend to Tillman, urged, "stand by the ticket, not for the ticket's sake, but for the party and the State". Even most Conservatives would not support a bolt from the party, and Kantrowitz suggested that Haskell and his supporters hated Tillman so much that his nomination caused them to commit political suicide. The Haskell campaign reached out to black voters, pledging that he would not disturb the limited political role played by African Americans in the state, a promise Tillman was unlikely to make.

During Tillman's five years of agricultural advocacy, he had rarely discussed the question of the African American. With blacks given control of one of South Carolina's seven congressional districts, the question of black influence in state politics seemed settled and did not play a significant role in the campaign for the Democratic nomination for governor. Haskell's appeals for support, added to speculation that Tillman was trying to form a biracial coalition through the Farmers' Alliance (which, though segregated, had a parallel organization for black farmers) made race an issue. Tillman boasted of his deeds at Hamburg and Ellenton, but it was Gary who made race the focus of his campaign. Urging segregation of railroad cars, Gary asked, "what white man wants his wife or sister sandwiched between a big bully buck and a saucy wench"?

Although Tillman fully expected to win, he warned that should he be defeated by ballot-box stuffing, there would be war. On Election Day, November 4, 1890, Tillman was elected governor with 59,159 votes to 14,828 for Haskell. With no Republican to support (none had run for governor since 1878), black leaders had been divided as to whether to endorse Haskell; in the end the only two counties won by him were in the lowcountry and heavily African-American. The losing candidate and his white supporters were quickly consigned to political oblivion, with some mocking them as "white Negroes".

Governor (1890–1894)

Inauguration and legislative control

Tillman was sworn in as governor in Columbia on December 4, 1890, before a crowd of jubilant supporters, the largest to see South Carolina's governor inaugurated since Hampton's swearing-in. In his inaugural address, Tillman celebrated his victory, "the citizens of this great commonwealth have for the first time in its history demanded and obtained for themselves the right to choose her Governor; and I, as the exponent and leader of the revolution which brought about the change, am here to take the solemn oath of office ... the triumph of democracy and white supremacy over mongrelism and anarchy, of civilization over barbarism, has been most complete."

Tillman made it clear he was not content that African Americans were allowed even a limited role in the political life of South Carolina:

The legislature, at Tillman's recommendation, reapportioned itself, costing

Charleston County four of its twelve seats, and other lowcountry counties one each, with the seats going to the upcountry. Although Tillman sought to reduce public expenditures, he was not successful in doing so as his reform program required spending, and the legislature could find few savings to make. Construction of Clemson College was slowed, and subsidies for fairs were cut.

Among the matters before the new, Tillman-controlled legislature was who should fill the Senate seat held by Hampton, whose term expired in March 1891—until 1913, state legislatures elected senators. There was a call from many in the South Carolina Democratic Party to re-elect Hampton, who had played a major role in the state for the past thirty years, in war and peace. Tillman was embittered against Hampton for a number of slights, including the senator's neutrality in the race against Haskell. The legislature retired Hampton, who received only 43 of 157 votes, and sent Irby to Washington in his place. The ouster of Hampton was controversial, and remained so for decades afterwards; according to Simkins (writing in 1944), "to future generations of South Carolinians, Tillman's act was a ruthless violation of cherished traditions of which Hampton was a living symbol".

Policies and events as governor

Lynching and race

Tillman as governor initially took a strong stand against lynching. The Shell Manifesto, in reciting the ills of Conservative government, had blamed the Bourbons for encouraging lynching through bad laws and poor administration. Although Governor Richardson, Tillman's predecessor, had taken action to prevent such murders, they still occurred, with no one being prosecuted for them. In about half of the lynchings in South Carolina between 1881 and 1895, there were claims that the black victim had raped or tried to rape a white woman, though studies have shown that lynchings were tied instead to economic and social issues. More lynchings took place in South Carolina in the 1890s than in any other decade, and in Edgefield and several other counties, such killings outnumbered lawful executions.

During Tillman's first year in office there were no lynchings, compared with 12 in Richardson's last year, which Simkins attributed to Tillman's "vigorous attitude towards law enforcement". Tillman called out the militia multiple times to prevent lynchings, and corresponded with sheriffs, passing along information and rumors of contemplated lynchings. The governor pressed for a law requiring the segregation of railroad cars: opposed by railroad companies and the few black legislators, the bill passed the state

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

but failed in the Senate. Tillman's calls to redistrict away the one congressional district dominated by African Americans, and for a constitutional convention to disenfranchise them also fell in the Senate, where the convention proposal failed to attract the necessary two-thirds majority. The only enactment that struck at the African American in Tillman's first term imposed a prohibitive tax on labor agents, who were recruiting local farm hands to move out of state.

In December 1891, soon after the first anniversary of Tillman's taking office, a black Edgefield man named Dick Lundy was charged with murdering the sheriff's son, and was taken from the jail and lynched. Tillman sent the state solicitor to Edgefield to investigate the matter, and ridiculed the coroner's jury verdict. As usual in cases of lynching, it stated the deceased had been killed by persons unknown. Tillman said, "the law received a wound for every bullet shot into Dick Lundy's body." The ''News and Courier'' opined that had he been present "with true Edgefield instinct,

illmanwould probably have been hanging around on the edge of the mob".

In April 1893, Mamie Baxter, a fourteen-year-old girl in

Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

,

Barnwell County, alleged that an African American unknown to her had attempted to attack her. About twenty black men were detained and paraded before her; she stated that Henry Williams looked something like the man she had seen. Placed on what passed for a trial by the mob that took him from the jail, Williams produced several respected white men to support his alibi. A majority of the mob voted against killing him, and Williams was returned to jail. More searches were made for Baxter's attacker. A suspect in the case, John Peterson, appealed to Tillman for protection, fearing he would be lynched if taken to Denmark, and stating he could prove his innocence. Tillman sent Peterson to Denmark with a single guard. He was taken by the mob, put on "trial", and after the mob found him guilty, was murdered. There was widespread outrage among both races across the country, both at the actions of the lynchers and at what Tillman had done. The governor said, in response, that he had assumed that, as the mob had been convinced by Williams' defense, it would allow Peterson to prove his innocence as well. He thereafter ignored the issue of the Denmark lynching.

There were five lynchings in South Carolina during Tillman's first term, and thirteen during his second. Tillman had to walk a narrow line in the debates over lynching, since most of his supporters believed in the collective right of white men in a community to dispense mob justice, especially in cases of alleged rape. Yet as governor, he was sworn to uphold the rule of law. He attempted to finesse the matter by seeking to appeal to both sides, demanding that the law be followed, but that he would, as he stated in 1892, "willingly lead a mob in lynching a Negro who had committed an assault on a white woman". Under criticism, he amended this to a willingness to lead the lynching of "a man of any color who assaults a virtuous woman of any color"—the adjective "virtuous" limiting the commitment, in Tillman's view, to assaults on white women.

During Tillman's second term, he had the legislature pass a bill to abolish elected local government, in favor of gubernatorial appointment of municipal and county officials. Tillman used this law to oust black officials even where that race held a voting majority.

In September 1893, South Carolina was hit by storms. Tillman discouraged northerners from sending aid to African Americans, fearing it would result in "lazy, idle crowds

anting todraw rations, as in the days of the

Freedmen's Bureau ... They cannot be treated as we would white people."

During the 1895 South Carolina state constitutional convention, however, Tillman supported a provision that permitted the removal from office of sheriffs who through negligence or connivance permitted a lynching. He also supported a provision that held the county where the lynching occurred liable for damages of $2,000 or more to be paid to the heirs of the victim.

Alcohol and the dispensary

The question of

prohibition of alcohol

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic be ...

was a major issue in South Carolina during Tillman's governorship. Tillman opposed banning alcohol, but was careful to speak well of temperance advocates, many of whom were women. The concern Tillman had with alcohol issues was that they divided the white community, leaving openings for black Republicans to exploit.

In the 1892 election, South Carolinians passed a non-binding referendum calling for prohibition. Bills were introduced into both houses of the state legislature that December to accomplish this, and passed the House of Representatives. Before the House bill could be passed by the Senate, Tillman sent a proposal in the form of an amendment, with instructions to pass the amended bill, and enact nothing else on the subject. Based on a system that had been successful in

Athens, Georgia

Athens, officially Athens–Clarke County, is a consolidated city-county and college town in the U.S. state of Georgia. Athens lies about northeast of downtown Atlanta, and is a satellite city of the capital. The University of Georgia, the sta ...

, the bill banned the private sale of alcohol, setting up a system of

dispensaries

A dispensary is an office in a school, hospital, industrial plant, or other organization that dispenses medications, medical supplies, and in some cases even medical and dental treatment. In a traditional dispensary set-up, a pharmacist dispense ...

that would sell alcohol in sealed containers—sale by the drink, and consumption on the premises, would not be permitted. Both houses passed Tillman's amendment, though there was opposition both within and outside the legislature. The dispensary system went into effect on July 1, 1893.

The new law was met with considerable resistance, especially in the towns and cities, where Tillman had less support. Dozens of clandestine saloons opened, fueled by barrels of illicit liquor, often transported by railroad. Tillman appointed dispensary constables, who tried to seize such shipments, to be frustrated by the fact that the

South Carolina Railroad was in federal receivership, and state authorities could not confiscate goods entrusted to it. All of Tillman's constables were white, placing him at a disadvantage in dealing with the alcohol trade among African Americans. Some of the constables tried going

undercover

To go "undercover" (that is, to go on an undercover operation) is to avoid detection by the object of one's observation, and especially to disguise one's own identity (or use an assumed identity) for the purposes of gaining the trust of an ind ...

by

blacking their faces like

minstrels

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in Middle Ages, medieval Europe. It originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobatics, acrobat, singer or jester, fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to ...

; later, Tillman hired an African-American detective from Georgia.

The small city of

Darlington became a center of the

bootlegging trade, with many illegal saloons. Tillman repeatedly warned the local mayor to crack down; when this did not occur, in April 1894, Tillman sent a train full of constables and other enforcement personnel to Darlington. They were repelled by gunfire, with dead on both sides. Tillman called out the state militia, which put down the unrest, though some units refused to serve. After the incident, Tillman disbanded the units of the militia that had refused his orders, and organized new companies to serve in their place. The Darlington riot divided the state politically as Tillman prepared to seek Butler's seat in the Senate, which would be filled by the legislature in December 1894.

Only weeks after the Darlington affair, the

South Carolina Supreme Court

The South Carolina Supreme Court is the highest court in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The court is composed of a Chief Justice and four Associate Justices. declared the act creating the dispensary system in violation of the state constitution on the grounds that the government had no right to run a profit-making business. The vote was 2–1, with Justice Samuel McGowan in the majority. McGowan was a

lame duck in office; Lieutenant Governor Gary had been elected to fill his seat effective August 1, 1894. Tillman closed the dispensaries temporarily, resulting in prohibition in South Carolina, and fired the constables. He had taken the precaution, once the court agreed to take the dispensary case, of having the 1893 legislature pass a revised dispensary law. When Gary took the bench, the Tillmanites would have a majority on the state Supreme Court, and Tillman instructed trial justices not to hear challenges to the 1893 law until after August 1. Tillman kept the law suspended until then, afterwards reopening the dispensaries under that statute. The high court declared the 1893 act constitutional on October 8, 1894, 2–1, with Gary voting in the majority.

Agriculture and higher education

Elected with support from the Farmers' Alliance and as a result of agricultural protest, Tillman was thought likely to join the Populists in their challenge to the established parties. Tillman refused, and generally opposed Populist positions that went beyond his program of increasing access to higher education and reform of the Democratic Party (white supremacy was not a Populist position). The Alliance (and Populists) demanded a system of subtreasuries under the federal government, that could accept farmers' crops and advance them 80 percent of the value interest-free. Tillman, not wanting more federal officeholders in the state (that in Republican administrations might be filled by African Americans), initially opposed the proposal. Many farmers felt strongly about this issue, and in 1891, Tillman was censured by the state Alliance for his opposition. Attuned to political necessities, Tillman gradually came to support the subtreasuries in time for his re-election campaign in 1892, though he was never an active proponent.

Tillman spoke at the opening of Clemson College on July 6, 1893. He fulfilled his campaign promise to start a women's college. In 1891, the legislature passed a bill creating the South Carolina Industrial and Winthrop Normal College (today

Winthrop University

Winthrop University is a public university in Rock Hill, South Carolina. It was founded in 1886 by David Bancroft Johnson, who served as the superintendent of Columbia, South Carolina, schools. He received a grant from Robert Charles Winthrop, ...

). He took a personal interest in the bidding by various towns around the state for the new school, and supported the successful candidate, the progressive town of

Rock Hill, on the state's northern border. Rock Hill officials had offered land, cash, and building materials. The school, then admitting only white women, opened in October 1895, after Tillman had become a senator.

Re-election in 1892

Tillman sought election to a second two-year term in 1892, presenting himself as a reforming alternative to the Conservatives. In the campaign, Tillman was a strong supporter of

free silver or

bimetallism, making silver

legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in ...

at the historic ratio to gold of 16:1. Such a policy would inflate the currency, and Tillman felt that would make it easier for the farmer to repay debts. The rhetoric of free silver suited Tillman as well, as he could make himself appear the champion of the farmer against the powerful interests that had committed the "

Crime of '73" (as silver supporters termed the act ending bimetallism in the United States).

Announcing that a primary for 1892, as had been prescribed two years before, was anti-reform, Tillman put off the first Democratic gubernatorial primary in the state until 1894. Thus, the nominee would be chosen by a convention, and mid-1892 saw a lengthy series of debates between Tillman and his challenger, former governor

John C. Sheppard. The bitter campaign was marked by violence, often set off by provocative language from the candidates. According to Kantrowitz, Tillman "sought to prolong the confrontation, to take the crowd up to the edge of violence, demonstrating his identification with his farmers without quite provoking them to murder". When former senator Hampton attempted to speak on Sheppard's behalf, he was shouted down by Tillman partisans; opponents complained that Tillman's supporters had formed a mob, and that the governor was a true son of violent Edgefield.

As the likely Democratic presidential candidate for 1892, former president

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, was a staunch opponent of free silver, Tillman attacked Cleveland. Most of the South Carolina delegation, including Tillman, voted against Cleveland at

the convention, but when the former president was nominated, the governor worked to deliver South Carolina for Cleveland by an overwhelming margin. Cleveland was elected, but the new president was offended by Tillman's earlier attacks, and denied the governor any role in patronage in South Carolina, entrusting it to Senator Matthew Butler and other remaining Conservatives. Tillman's inability to provide federal jobs for supporters made it more difficult for him to hold his coalition together. Tillman continued his verbal assaults, stating that Cleveland "is an old bag of beef and I am going to Washington with a pitchfork and prod him in his old fat ribs"—thus popularizing Tillman as "Pitchfork Ben".

During the 1892 campaign, Tillman called for the defeat in the Democratic primary for the legislature of most of the men elected as his supporters, urging the selection of more loyal men. Tillman urged the voters, "turn out this cattle, these driftwood legislators, and send me a legislature that will do what I say, and I'll show you reform." South Carolinians dutifully voted out their representatives as Tillman requested. Although no primary for governor was permitted, the delegates to the nominating convention were elected by the Democratic voters, and Tillman won an overwhelming victory over Sheppard, who took only 4 of 35 counties. The convention was mostly Tillmanite, and gave the governor an easy triumph. The Conservatives had agreed not to bolt the party, and Tillman won uncontested re-election.

Senate election of 1894

Tillman had long seen a Senate seat as a logical next step once he concluded his time as governor. Senator Butler, whose term expired in March 1895, had soon after the 1890 election begun to shift his positions towards Tillman's, hoping to retain Conservative backing while appealing to the governor's supporters. The senator signed on to most demands of the Farmers' Alliance, and did not support the forces trying to prevent Tillman's re-nomination in 1892. Butler's seeming apostasy disheartened Conservatives, who did not bother to run candidates for the legislature in many counties in 1894, abandoning the field (and Butler's Senate seat) to the Tillmanites. The governor took nothing for granted, seeing to it that popular candidates, loyal to him, ran for the legislature. In addition to electing Tillman to the Senate, these legislators could help preserve his gubernatorial legacy, including the dispensary.

Butler was aware of the uphill struggle he faced, and called for a primary for senator, with all Democratic legislators committed to vote to elect the winner. Tillman, who had already finalized his plans to win in the legislature, refused. The series of debates that marked a campaign summer in South Carolina began on June 18, 1894. Butler believed he could still win by appealing to the electorate in the same manner as Tillman; the senator thought he understood the lessons of 1876 as well as anyone. In the debates, Butler and Tillman matched slander for slander, with Butler claiming that at Hamburg, when the shooting started, Tillman was "nowhere to be found". Tillman shot back that when Butler had testified before Congress about Hamburg, he had downplayed his role in the events. According to Kantrowitz, "their struggle over the legacy of 1876 was in part over who could more legitimately claim to have murdered" African Americans. Tillman's partisans shouted down Butler when he tried to speak at some debates. Although this tactic had been used by Butler and other Democrats against the Republicans in 1876, Butler now decried it as "not Christian civilization to howl anyone down".

Balked again, Butler attempted to turn the campaign personal, calling Tillman a liar and trying to strike him. Tillman warned that Butler's tactics risked sundering white unity, stating to a questioner who asked why he did not meet Butler's insults with violence, "Yes, I tell you, you cowardly hound, why I took them

he insults and I'll meet you wherever you want to. I took them because I, as governor of the State, could not afford to create a row at a public meeting and have our people murder each other like dogs."

By early July, Butler had realized the futility of his race, and took to ignoring Tillman in his speeches, which the governor reciprocated, taking much of the drama from the debates. The two men even rode in the same carriage on July 4. Nevertheless, Butler refused to surrender, even after the primary for the legislature was overwhelmingly won by the Tillmanites, threatening action in the courts and an election contest before the Senate. On December 11, 1894, Benjamin Tillman was elected to the Senate by the new legislature with 131 votes. Butler received 21 and three votes were scattered.

Senator (1895–1918)

Disenfranchising the African American: 1895 state constitutional convention

Throughout his time as governor, Tillman had sought a convention to rewrite South Carolina's Reconstruction-era constitution. His main purpose in doing so was to

disenfranchise African Americans. They opposed Tillman's proposal, as did others, who had seen previous efforts to restrict the franchise rebound against white voters. Tillman was successful in getting the legislature to place a referendum for a constitutional convention on the November 1894 general election ballot. It passed by 2,000 votes statewide, the narrow margin gained, according to Kantrowitz, most likely through fraud.

John Gary Evans

John Gary Evans (October 15, 1863June 26, 1942) was the 85th governor of South Carolina from 1894 to 1897.

Early life

Evans was born in Cokesbury, South Carolina to an aristocratic and well-connected family. His father was Nathan George E ...

was elected Tillman's successor as governor.

Opponents sued in the courts to overturn the referendum result; they were unsuccessful. During the convention, Tillman hailed it as "a fitting capstone to the triumphal arch which the common people have erected to liberty, progress, and Anglo-Saxon civilization since 1890". To assure white unity, Tillman allowed the election of Conservatives as about a third of delegates. The convention assembled in Columbia in September 1895, consisting of 112 Tillmanites, 42 Conservatives, and six African Americans. Tillman called black disenfranchisement "the sole cause of our being here".

Tillman was the dominant figure of the convention, chairing the Committee on the Rights of Suffrage, which was to craft language to accomplish the disenfranchisement. Constrained by the requirement of the federal

Fifteenth Amendment that men of all races be allowed to vote, the committee sought language that though superficially nondiscriminatory would operate or could be used to take the vote from most African Americans.

Tillman spoke to the convention on October 31. In addition to supporting the provisions of the draft document, he recalled 1876:

The adopted provisions, which came into force after the new constitution was ratified by the convention in December 1895, set a maze of obstacles before prospective voters. Voters had to be a resident of the state two years, the county one year, and the precinct for four months. Many African Americans were itinerant laborers, and this provision disproportionately affected them. A

poll tax had to be paid six months in advance of the election, in May when laborers had the least cash. Each registrant had to prove to the satisfaction of the county board of elections that he could read or write a section of the state constitution (in a literacy or comprehension test), or that he paid taxes on property valued at $300 or more. This allowed white registrars ample discretion to disenfranchise African Americans. Illiterate whites were shielded by the "understanding" clause, that allowed, until 1898, permanent registration to citizens who could "understand" the constitution when read to them. This also allowed officials great leeway to discriminate. Even if an African American maneuvered past all of these blocks, he still faced the manager of the polling place, who could demand proof he had paid all taxes owed—something difficult to show conclusively. Conviction of any of a long list of crimes that whites believed prevalent among African Americans was made the cause of permanent disenfranchisement, including bigamy, adultery, burglary, and arson. Convicted murderers not in prison had their franchise undisturbed.

Tillman defended this on the floor of the Senate:

In my State there were 135,000 negro voters, or negroes of voting age, and some 90,000 or 95,000 white voters.... Now, I want to ask you, with a free vote and a fair count, how are you going to beat 135,000 by 95,000? How are you going to do it? You had set us an impossible task.

We did not disfranchise the negroes until 1895. Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took the matter up calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disfranchising as many of them as we could under the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. We adopted the educational qualification as the only means left to us, and the negro is as contented and as prosperous and as well protected in South Carolina to-day as in any State of the Union south of the Potomac. He is not meddling with politics, for he found that the more he meddled with them the worse off he got. As to his "rights"—I will not discuss them now. We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will.... I would to God the last one of them was in Africa and that none of them had ever been brought to our shores.

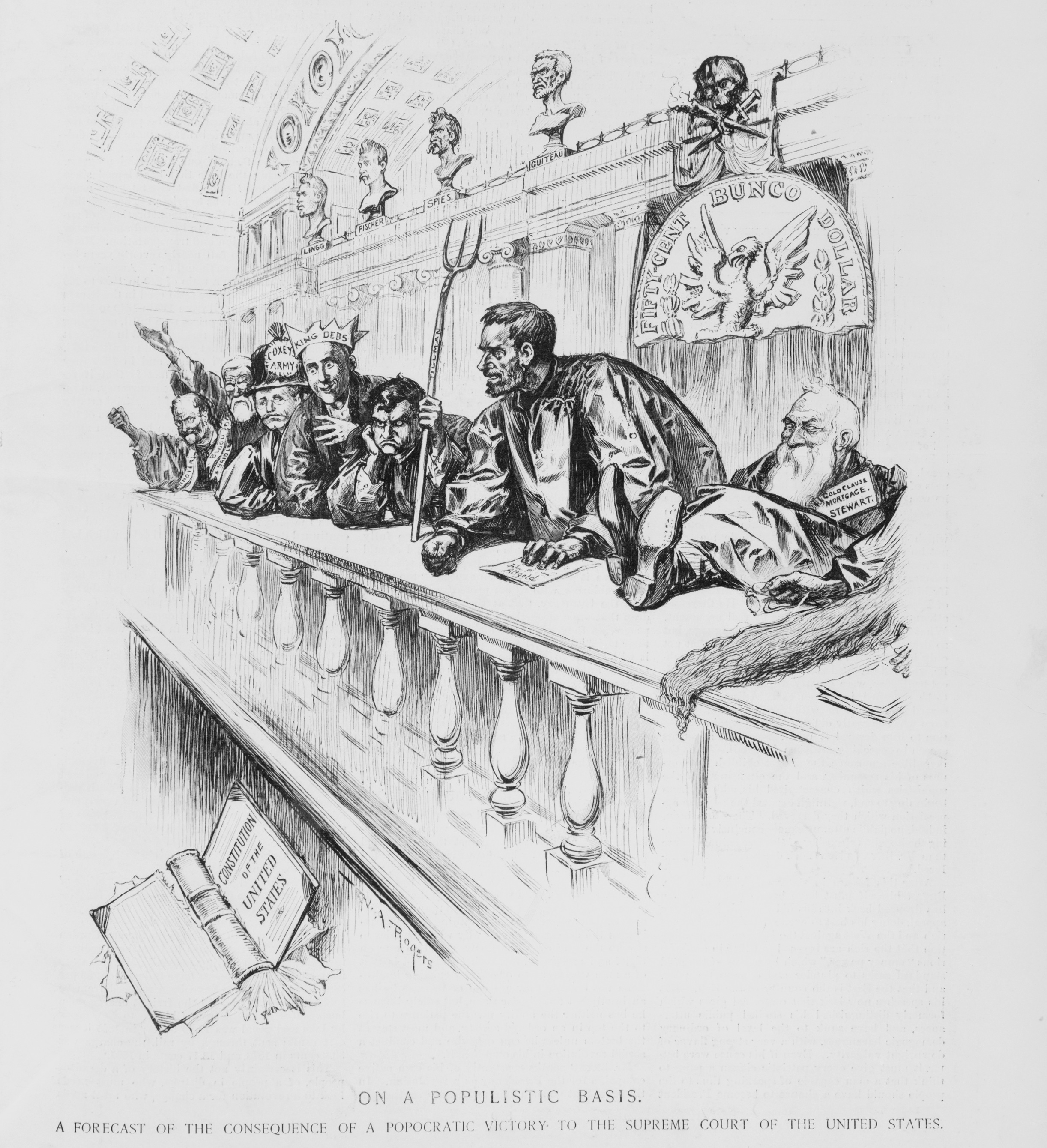

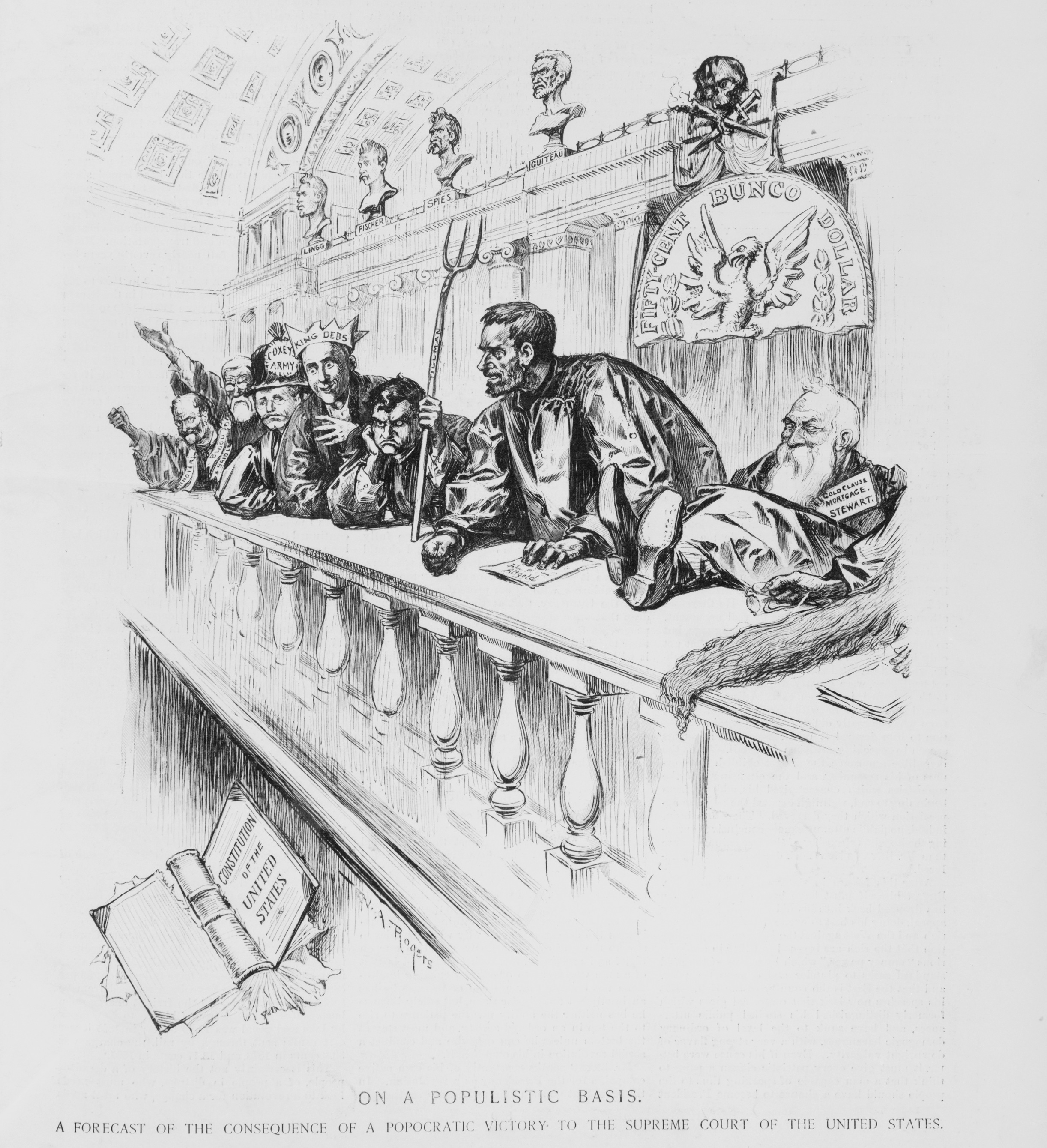

1896 presidential bid

By early 1896, many in the Democratic Party were bitterly opposed to President Cleveland and his policies. The United States was by then in the third year of a deep recession, the

Panic of 1893. Cleveland was a firm supporter of the gold standard, and soon after the recession began forced through repeal of the

Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

, which he believed had helped cause it.

Sherman's act, although not restoring bimetallism, had required the government to purchase and coin large quantities of silver bullion, and its repeal outraged supporters of free silver. Other Cleveland policies, such as his forcible suppression of the

Pullman strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

, led to the Democrats losing control of both houses of Congress in the 1894 midterm elections, and to a revolt against him by silver supporters within his party.

From the time of his swearing-in in December 1895 (when Congress began its annual session), Tillman was seen as the voice of the dissatisfied in the nation; the ''

New York Press

''New York Press'' was a free alternative weekly in New York City, which was published from 1988 to 2011.

The ''Press'' strove to create a rivalry with the ''Village Voice''. ''Press'' editors claimed to have tried to hire away writer Nat Hent ...

'' stated Tillman would voice the concerns of "the masses of the people of South Carolina far more faithfully than did the Bourbon politician Butler". He shocked the Senate with dramatic attacks on Cleveland, calling the president "the most gigantic failure of any man who ever occupied the White House, all because of his vanity and obstinacy". ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' deemed Tillman "a filthy baboon, accidentally seated in the Senate chamber".

Tillman believed that the nation was on the verge of major political change, and that he could be elected president in 1896, uniting the silver supporters of the South and West. He was willing to consider a third party bid if Cleveland kept control of the Democratic Party, but felt the Populists, by allowing African Americans to seek office, had destroyed their credibility among southern whites. The stinging oratory of the South Carolina senator brought him national prominence, and with the

1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36, B ...

in Chicago likely to be controlled by silver supporters, Tillman was spoken of as a possible presidential candidate along with others, such as former Missouri representative

Richard P. Bland, Texas Governor

Jim Hogg, and former Nebraska congressman

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

.

Tillman was his state's

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

candidate, and its representative on the Committee on Resolutions (often called "the Platform Committee"). The platform had the support of the pro-silver majority of the committee, but the gold minority, led by New York Senator

David B. Hill

David Bennett Hill (August 29, 1843October 20, 1910) was an American politician from New York who was the 29th Governor of New York from 1885 to 1891 and represented New York in the United States Senate from 1892 to 1897.

In 1892, he made an u ...

, opposed its support of free silver, and wanted to take the disagreement to the convention floor. With one hour and fifteen minutes allocated to each side, Tillman and Bryan were selected as the speakers in favor of the draft platform. Bryan asked Tillman if he wanted to open or close the debate; the senator wanted to close, but sought fifty minutes to do so. The Nebraskan replied that Hill would oppose such a long closing address, and Tillman agreed to open the debate, with Bryan to close it.

When the platform debate began in the

Chicago Coliseum on the morning of July 9, 1896, Tillman was the opening speaker. Although met with applause and shouts of his name, he "spoke in the same manner that had won him success in South Carolina, cursing, haranguing his enemies, and raising the specter of sectionalism. He, however, thoroughly alienated the national audience".

According to Richard Bensel in his study of the 1896 convention, Tillman gave "by far, the most divisive speech of the convention, an address that embarrassed the silver wing of the party as much as it enraged the hard-money faction". He deemed silver a sectional issue, pitting the wealthy East against the oppressed South and West. This upset delegates, who wished to view silver as a patriotic, national issue, and some voiced their dissent, disagreeing with Tillman. The senator alternately offended, confused, and bored the delegates, who shouted for Tillman to stop even though less than half of his time had expired. Beset by shouting delegates and one of the convention bands, which unexpectedly appeared and began to play, Tillman nevertheless pressed on, "the audience might just as well understand that I am going to have my say if I stand here until sundown." By the time he had his say, he had "effectively destroyed his chances to become a national candidate". With Tillman's candidacy stillborn (only his home state voted for him), Bryan seized the opportunity to deliver an address in support of silver that did not rely on sectionalism. His

Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported " free silver" (i.e. bim ...

won him the presidential nomination.

After Tillman returned from Chicago to South Carolina, he suggested he had delivered an intentionally radical speech so as to allow Bryan to look statesmanlike by comparison. This interpretation was mocked by his enemies. Tillman is not known to have otherwise discussed his feelings at the failure of his presidential bid, and the political grief was likely overwhelmed by personal sadness a week after the convention when his beloved daughter Addie died, struck by lightning on a North Carolina mountain. Tillman campaigned for Bryan, but was a favorite target of cartoonists denigrating the Democratic candidate and supporting the Republican, former Ohio governor

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

. Bryan had also been nominated by the Populists, who selected their own vice presidential candidate, Georgia's

Thomas E. Watson. Tillman was active in efforts to get Watson to withdraw, having a 12-hour meeting with the candidate, apparently without result. Tillman traveled widely to speak on Bryan's behalf, and drew large crowds, but his speeches were of little significance. Despite undertaking

an arduous campaign, Bryan lost the election. Simkins suggested that Tillman, by helping forge an image of the Democratic Party as anarchic, contributed to Bryan's defeat.

Wild man of the Senate: Tillman-McLaurin fistfight

Kantrowitz deemed Tillman "the Senate's wild man", who applied the same techniques of accusation and insinuation that had served him well in South Carolina. In 1897, Tillman accused the Republicans, "I certainly do not want to attack any member of the committee who does not deserve to be attacked

utnobody denies that there have been rooms occupied for two months by the Republicans on the Senate Finance Committee at the Arlington Hotel ... in easy reach of the sugar trust". Simkins, though, opined that Tillman's speeches in the Senate were only inflammatory because of his injection of personalities, and if that is disregarded, his speeches, when read, come across as well-reasoned and even conservative.

In 1902, Tillman accused his junior colleague from South Carolina,

John L. McLaurin, of corruption in a speech to the Senate. McLaurin, who had been a Tillmanite before breaking from him after being elected to the Senate, called him a liar, whereupon Tillman rushed across the Senate floor and punched McLaurin in the face; McLaurin responded by punching Tillman in the nose before the

Sergeant at Arms

Sergeant ( abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other un ...

and other Senators intervened. The body immediately went into closed session, and held both men in contempt.

The Senate considered suspending them, but Tillman argued that it was unfair to deprive South Carolina of her representation, though the body could have also expelled the two men, knowing he had enough Democratic votes to prevent this. In the end, both men were censured, and later that year, Tillman arranged for McLaurin, whose term ended in 1903, to not be re-elected.

The fracas with McLaurin caused President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, who had succeeded the

assassinated McKinley in 1901, to withdraw an invitation to dinner at the White House. Tillman never forgave this slight, and became a bitter enemy of Roosevelt.

Tillman was inclined to oppose Roosevelt anyway, who soon after becoming president,

dined at the White House with

Booker T. Washington, an African American. Tillman responded by saying "the action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they learn their place again."

Race relations

Tillman believed, and often stated as senator, that blacks must submit to either white domination or extermination. He was reluctant to undertake the latter, fearing hundreds of whites would die accomplishing it. He campaigned in the violent 1898 North Carolina elections, in which white Democrats were determined to take back control from a biracial Populist-Republican coalition elected in 1894 and 1896 on a fusion ticket. He spoke widely in North Carolina in late 1898, often to crowds wearing red shirts, disheartening his Populist supporters. On October 20, 1898, Tillman was the featured speaker at the Democratic Party's Great White Man's Rally and Basket Picnic in Fayetteville. Tillman spoke furiously to the crowd of white men, asking them why North Carolina had not rid itself of black office holders as South Carolina had in 1876. He chastized the audience for not lynching

Alex Manly, the black editor of the Wilmington ''Daily Record''. Tillman was one of many prominent Democrats advocating use of violence to win the 1898 election.

The resulting coup expelled opposition black and white political leaders from Wilmington, destroyed the property and businesses of black citizens built up since the Civil War, including the only black newspaper in the city, and killed an estimated 60 to more than 300 people.

Terror and intimidation again won the day for the Democrats, who were elected statewide. South Carolina saw violence as well: an effort to register black voters in

Phoenix led whites to provoke a confrontation, after which a number of African Americans were murdered. Tillman warned African Americans and those who might combine with them that black political activism would provoke a murderous response from whites.

Beginning in 1901, Tillman joined the

Chautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua br ...

circuit, giving well-paid speeches throughout the nation. Tillman's reputation, both for his views and his oratory, attracted large crowds. Tillman informed them that African Americans were inferior to the white man, but were not baboons, though some were "so near akin to the monkey that scientists are yet looking for the missing link". Given that in Africa, they were an "ignorant and debased and debauched race" with a record of "barbarism, savagery, cannibalism and everything that is low and degrading", it was the "quintessence of folly" to believe that the black man should be placed on an equal footing with his white counterpart. Tillman "embraced segregation as divinely imperative".

Tillman told the Senate, "as governor of South Carolina, I proclaimed that, although I had taken the oath of office to support the law and enforce it, I would lead a mob to lynch any man, black or white, who ravished a woman, black or white." He told his colleagues, "I have three daughters, but, so help me God, I had rather find either one of them killed by a tiger or a bear

nd die a virginthan to have her crawl to me and tell me the horrid story that she had been robbed of the jewel of her womanhood by a black fiend." In 1907, he told the senators about the