Battle of the Crater on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

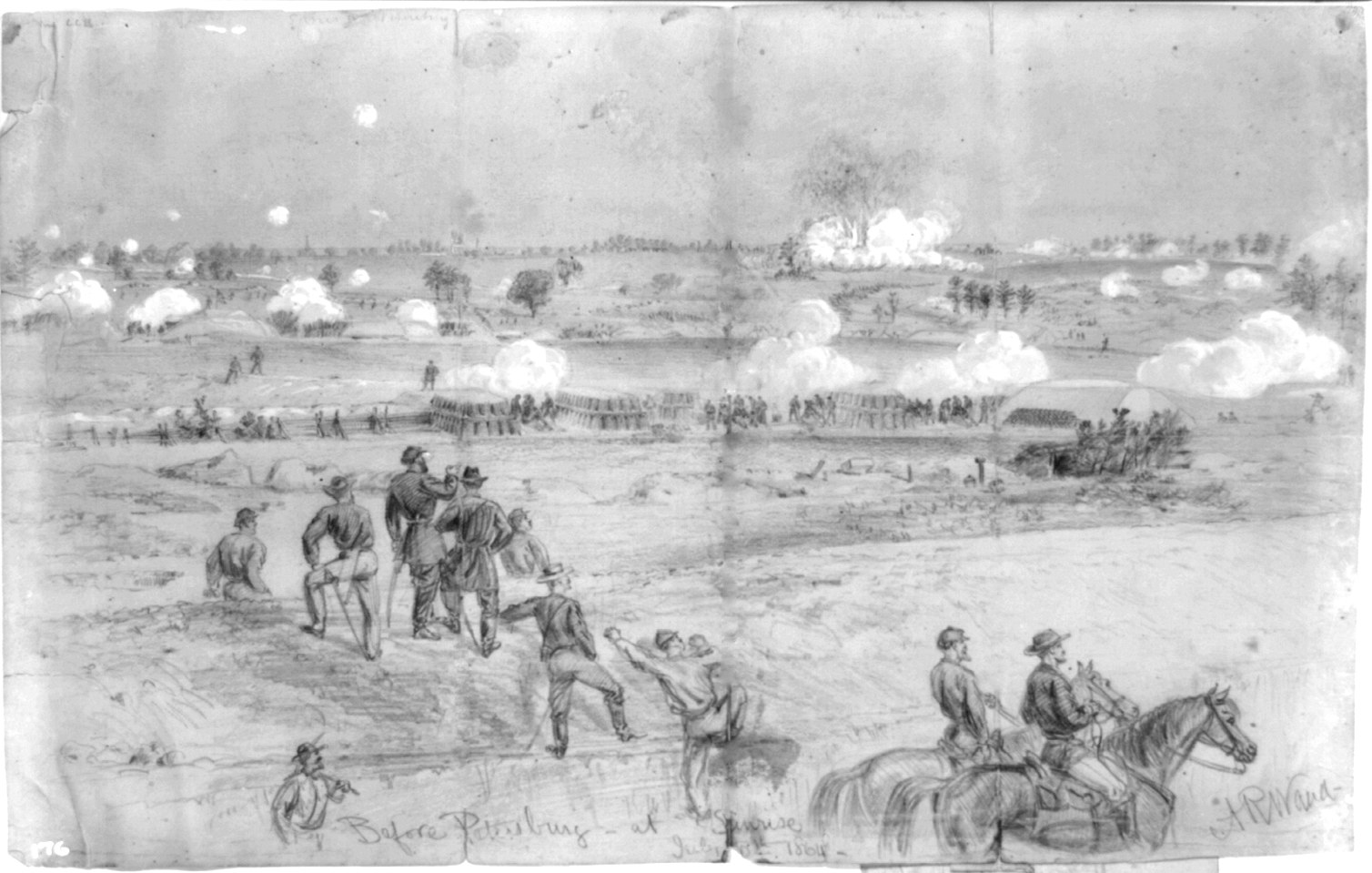

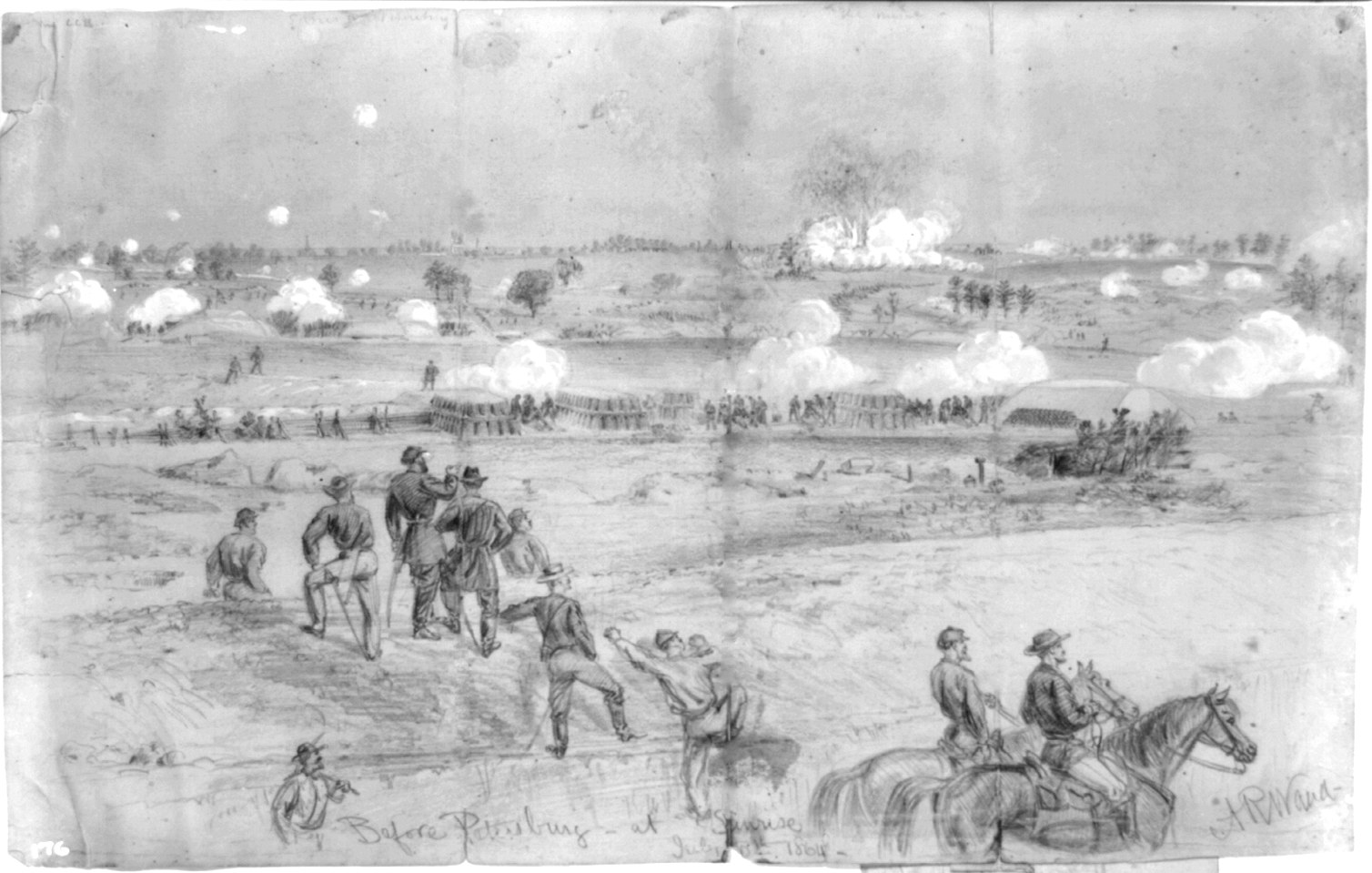

The Battle of the Crater was a battle of the

Digging began in late June, but even Grant and Meade saw the operation as a "mere way to keep the men occupied" and doubted it of any actual tactical value. They quickly lost interest, and Pleasants soon found himself with few materials for his project, and his men even had to forage for wood to support the structure.

Work progressed steadily, however. Earth was removed by hand and packed into improvised sledges made from cracker boxes fitted with handles, and the floor, wall, and ceiling of the mine were shored up with timbers from an abandoned wood mill and even from tearing down an old bridge.

The shaft was elevated as it moved toward the Confederate lines to make sure moisture did not clog up the mine, and fresh air was drawn in by an ingenious air-exchange mechanism near the entrance. A canvas partition isolated the miners' air supply from outside air and allowed miners to enter and exit the work area easily. The miners had constructed a vertical exhaust shaft located well behind Union lines. At the vertical shaft's base, a fire was kept continuously burning. A wooden duct ran the entire length of the tunnel and protruded into the outside air. The fire heated stale air inside of the tunnel, drawing it up the exhaust shaft and out of the mine by the

Digging began in late June, but even Grant and Meade saw the operation as a "mere way to keep the men occupied" and doubted it of any actual tactical value. They quickly lost interest, and Pleasants soon found himself with few materials for his project, and his men even had to forage for wood to support the structure.

Work progressed steadily, however. Earth was removed by hand and packed into improvised sledges made from cracker boxes fitted with handles, and the floor, wall, and ceiling of the mine were shored up with timbers from an abandoned wood mill and even from tearing down an old bridge.

The shaft was elevated as it moved toward the Confederate lines to make sure moisture did not clog up the mine, and fresh air was drawn in by an ingenious air-exchange mechanism near the entrance. A canvas partition isolated the miners' air supply from outside air and allowed miners to enter and exit the work area easily. The miners had constructed a vertical exhaust shaft located well behind Union lines. At the vertical shaft's base, a fire was kept continuously burning. A wooden duct ran the entire length of the tunnel and protruded into the outside air. The fire heated stale air inside of the tunnel, drawing it up the exhaust shaft and out of the mine by the

The plan called for the mine to be detonated between 3:30 and 3:45 a.m. on the morning of July 30. Pleasants lit the fuse accordingly, but as with the rest of the mine's provisions, they had been given poor-quality fuses, which his men were forced to splice themselves. After more and more time passed and no explosion occurred (the impending dawn creating a threat to the men at the staging points, who were in view of the Confederate lines), two volunteers from the 48th Regiment (Lt. Jacob Douty and Sgt. Harry Reese) crawled into the tunnel. After discovering the fuse had burned out at a splice, they spliced on a length of new fuse and relit it. Finally, at 4:44 a.m., the charges exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns. A crater (still visible today) was created, long, wide, and at least deep.

The explosion immediately killed 278 Confederate soldiers of the 18th and 22nd South Carolina and the stunned Confederate troops did not direct any significant rifle or artillery fire at the enemy for at least 15 minutes. However, Ledlie's untrained division was not prepared for the explosion, and reports indicate they waited 10 minutes before leaving their own entrenchments. Footbridges were supposed to have been placed to allow them to cross their own trenches quickly. Because they were missing, however, the men had to climb into and out of their own trenches just to reach no-man's land. Once they had wandered to the crater, instead of moving around it, as the troops had been trained, they thought that it would make an excellent rifle pit in which to take cover. They therefore moved down into the crater itself, wasting valuable time and realizing too late that the crater was much too deep and exposed to function as a rifle pit and quickly becoming overcrowded while the Confederates, under Brigadier General

The plan called for the mine to be detonated between 3:30 and 3:45 a.m. on the morning of July 30. Pleasants lit the fuse accordingly, but as with the rest of the mine's provisions, they had been given poor-quality fuses, which his men were forced to splice themselves. After more and more time passed and no explosion occurred (the impending dawn creating a threat to the men at the staging points, who were in view of the Confederate lines), two volunteers from the 48th Regiment (Lt. Jacob Douty and Sgt. Harry Reese) crawled into the tunnel. After discovering the fuse had burned out at a splice, they spliced on a length of new fuse and relit it. Finally, at 4:44 a.m., the charges exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns. A crater (still visible today) was created, long, wide, and at least deep.

The explosion immediately killed 278 Confederate soldiers of the 18th and 22nd South Carolina and the stunned Confederate troops did not direct any significant rifle or artillery fire at the enemy for at least 15 minutes. However, Ledlie's untrained division was not prepared for the explosion, and reports indicate they waited 10 minutes before leaving their own entrenchments. Footbridges were supposed to have been placed to allow them to cross their own trenches quickly. Because they were missing, however, the men had to climb into and out of their own trenches just to reach no-man's land. Once they had wandered to the crater, instead of moving around it, as the troops had been trained, they thought that it would make an excellent rifle pit in which to take cover. They therefore moved down into the crater itself, wasting valuable time and realizing too late that the crater was much too deep and exposed to function as a rifle pit and quickly becoming overcrowded while the Confederates, under Brigadier General

''Battles and Leaders of the Civil War''

4 vols. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. . * Kennedy, Frances H., ed. ''The Civil War Battlefield Guide''. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Robertson, James I., Jr., and William Pegram. '"The Boy Artillerist": Letters of Colonel William Pegram, C.S.A.' '' The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' 98, no. 2 (The Trumpet Unblown: The Old Dominion in the Civil War), (1990), pp. 221–260.

* Lykes, Richard Wayne

''Campaign for Petersburg'', Ch. 6 "Battle of the Crater"

for the National Park Service, 1970 * Salmon, John S. ''The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. . * * Trudeau, Noah Andre. ''The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864 – April 1865''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991. .

CWSAC Report Update

Battle of the Crater in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

* ttp://www.beyondthecrater.com/siege-of-petersburg-resources/maps/petersburg-campaign-maps/third-offensive-maps/the-battle-of-the-crater-maps/ Battle of the Crater Maps {{authority control Crater Crater Crater Crater Petersburg, Virginia the Crater 1864 in Virginia July 1864 events Confederate war crimes

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, part of the siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

. It took place on Saturday, July 30, 1864, between the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

, commanded by General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Robert E. Lee, and the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

, commanded by Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

(under the direct supervision of the general-in-chief, Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

).

After weeks of preparation, on July 30 Union forces exploded a mine in Major General Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

's IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

sector, blowing a gap in the Confederate defenses of Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Econ ...

. At that point, everything deteriorated rapidly for the Union attackers. Unit after unit charged into and around the crater, where most of them milled in confusion in the bottom of the crater. Grant considered this failed assault as "the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war."

The Confederates quickly recovered, and launched several counterattacks led by Brigadier General William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was an American civil engineer, railroad executive, Confederate States Army general, and Virginia politician.

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in the building of Virginia's roads and railroa ...

. The breach was sealed off, and the Union forces were repulsed with severe casualties, while Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Edward Ferrero

Edward Ferrero (January 18, 1831 – December 11, 1899) was one of the leading dance instructors, choreographers, and ballroom operators in the United States. He also served as a Union Army general in the American Civil War, being most remembered f ...

's division of black soldiers were badly mauled. It may have been Grant's best chance to end the siege of Petersburg; instead, the soldiers settled in for another eight months of trench warfare.

Burnside was relieved of command for the final time for his role in the fiasco, and he was never again returned to command, and to make matters worse, Ferrero and General James H. Ledlie

James Hewett Ledlie (April 14, 1832 – August 15, 1882) was a civil engineer for American railroads and a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He is best known for his dereliction of duty at the Battle of the Crater during ...

were observed behind the lines in a bunker, drinking liquor throughout the battle. Ledlie was criticized by a court of inquiry into his conduct that September, and in December he was effectively dismissed from the Army by Meade on orders from Grant, formally resigning his commission on January 23, 1865.

Background

During the Civil War,Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Econ ...

, was an important railhead, where four railroad lines from the south met before they continued to Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, the capital of the Confederacy. Most supplies to General Lee's army and Richmond funneled through that location. Consequently, the Union regarded it as the "back door" to Richmond and as necessary for its defense. The result was the siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

. It was actually trench warfare, rather than a true siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

, as the armies were aligned along a series of fortified positions and trenches more than long, extending from the old Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S ...

battlefield near Richmond to areas south of Petersburg.

After Lee stopped Grant's attempt to seize Petersburg on June 15, the battle settled into a stalemate. Grant had learned a hard lesson at Cold Harbor about attacking Lee in a fortified position and was chafing at the inactivity to which Lee's trenches and forts had confined him. Finally, Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants

Henry Clay Pleasants (February 16, 1833 – March 26, 1880) was a coal mining engineer and an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He is best known for organizing the building of a tunnel filled with explosives under the Confe ...

, commanding the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry

The 48th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the "Schuylkill Regiment", was an infantry regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 48th Pennsylvania Infantry was recruited in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania an ...

of Major General Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

's IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

, offered a novel proposal to break the impasse.

Pleasants, a mining engineer from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in civilian life, proposed digging a long mine shaft under the Confederate Army lines and planting explosive charges directly underneath a fort (Elliott's Salient) in the middle of the Confederate First Corps line. If successful, not only would all the defenders in the area be killed, but also a hole in the Confederate defenses would be opened. If enough Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

troops filled the breach quickly enough and drove into the Confederate rear area, the Confederates would not be able to muster enough force to drive them out, and Petersburg might fall.

Burnside, whose reputation had suffered from his 1862 defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

and his poor performance earlier that year at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 186 ...

, agreed to Pleasants's plan.

Mine construction

Digging began in late June, but even Grant and Meade saw the operation as a "mere way to keep the men occupied" and doubted it of any actual tactical value. They quickly lost interest, and Pleasants soon found himself with few materials for his project, and his men even had to forage for wood to support the structure.

Work progressed steadily, however. Earth was removed by hand and packed into improvised sledges made from cracker boxes fitted with handles, and the floor, wall, and ceiling of the mine were shored up with timbers from an abandoned wood mill and even from tearing down an old bridge.

The shaft was elevated as it moved toward the Confederate lines to make sure moisture did not clog up the mine, and fresh air was drawn in by an ingenious air-exchange mechanism near the entrance. A canvas partition isolated the miners' air supply from outside air and allowed miners to enter and exit the work area easily. The miners had constructed a vertical exhaust shaft located well behind Union lines. At the vertical shaft's base, a fire was kept continuously burning. A wooden duct ran the entire length of the tunnel and protruded into the outside air. The fire heated stale air inside of the tunnel, drawing it up the exhaust shaft and out of the mine by the

Digging began in late June, but even Grant and Meade saw the operation as a "mere way to keep the men occupied" and doubted it of any actual tactical value. They quickly lost interest, and Pleasants soon found himself with few materials for his project, and his men even had to forage for wood to support the structure.

Work progressed steadily, however. Earth was removed by hand and packed into improvised sledges made from cracker boxes fitted with handles, and the floor, wall, and ceiling of the mine were shored up with timbers from an abandoned wood mill and even from tearing down an old bridge.

The shaft was elevated as it moved toward the Confederate lines to make sure moisture did not clog up the mine, and fresh air was drawn in by an ingenious air-exchange mechanism near the entrance. A canvas partition isolated the miners' air supply from outside air and allowed miners to enter and exit the work area easily. The miners had constructed a vertical exhaust shaft located well behind Union lines. At the vertical shaft's base, a fire was kept continuously burning. A wooden duct ran the entire length of the tunnel and protruded into the outside air. The fire heated stale air inside of the tunnel, drawing it up the exhaust shaft and out of the mine by the chimney effect

The stack effect or chimney effect is the movement of air into and out of buildings through unsealed openings, chimneys, flue-gas stacks, or other containers, resulting from air buoyancy. Buoyancy occurs due to a difference in indoor-to-outdoor ...

. The resulting vacuum then sucked fresh air in from the mine entrance via the wooden duct, which carried it down the length of the tunnel to the place in which the miners were working. That avoided the need for additional ventilation shafts, which could have been observed by the enemy, and it also easily disguised the diggers' progress.

On July 17, the main shaft reached under the Confederate position. Rumors of a mine construction soon reached the Confederates, but Lee refused to believe or act upon them for two weeks before he commenced countermining attempts, which were sluggish and uncoordinated, and were unable to discover the mine. However, General John Pegram

John Pegram (November 16, 1773April 8, 1831) was a Virginia planter, soldier and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives, both houses of the Virginia General Assembly and a major general during the War of 1812.

Ear ...

, whose batteries would be above the explosion, took the threat seriously enough to build a new line of trenches and artillery points behind his position as a precaution. Shafts were also sunk by the Confederates in an effort to intercept the passage. Pleasants became aware of the Confederate's counter-movements and was able to frustrate their effort by changing the direction of the main and lateral galleries while increasing their depth below the surface.

The mine was in a "T"-shape. The approach shaft was long, starting in a sunken area downhill and more than below the Confederate battery, making detection difficult. The tunnel entrance was narrow, about wide and high. At its end, a perpendicular gallery of extended in both directions. Grant and Meade suddenly decided to use the mine three days after it was completed after a failed attack known later as the First Battle of Deep Bottom

The First Battle of Deep Bottom, also known as Darbytown, Strawberry Plains, New Market Road, or Gravel Hill, was fought July 27–29, 1864, at Deep Bottom in Henrico County, Virginia, as part of the Siege of Petersburg of the American Civil ...

. Union soldiers filled the mine with 320 kegs of gunpowder, totaling . The explosives were approximately under the Confederate works, and the T-gap was packed shut with of earth in the side galleries. A further of packed earth was placed in the main gallery to prevent the explosion blasting out the mouth of the mine. On July 28, the powder charges were armed.

Preparation

Burnside had trained a division of United States Colored Troops (USCT) under Brigadier GeneralEdward Ferrero

Edward Ferrero (January 18, 1831 – December 11, 1899) was one of the leading dance instructors, choreographers, and ballroom operators in the United States. He also served as a Union Army general in the American Civil War, being most remembered f ...

to lead the assault. The division consisted of two brigades, one designated to go to the left of the crater and the other to the right. A regiment from both brigades was to leave the attack column and extend the breach by rushing perpendicular to the crater, and the remaining regiments were to rush through, seizing the Jerusalem Plank Road just beyond, followed by the churchyard and, if possible, Petersburg itself. Burnside's two other divisions, made up of white troops, would then move in, supporting Ferrero's flanks and race for Petersburg itself. Two miles (3 km) behind the front lines, out of sight of the Confederates, the men of the USCT division were trained for two weeks on the plan.

Despite the careful planning and intensive training, on the day before the attack, Meade, who lacked confidence in the operation, ordered Burnside not to use the black troops in the lead assault. He claimed that if the attack failed, black soldiers would be killed needlessly, creating political repercussions in the North. Meade may have also ordered the change of plans because he lacked confidence in the black soldiers' abilities in combat. Burnside protested to Grant, who sided with Meade. When volunteers were not forthcoming, Burnside selected a replacement white division by having the three commanders draw lots. Brigadier General James H. Ledlie

James Hewett Ledlie (April 14, 1832 – August 15, 1882) was a civil engineer for American railroads and a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He is best known for his dereliction of duty at the Battle of the Crater during ...

's 1st Division was selected, but he failed to brief the men on what was expected of them and was reported during the battle to be drunk, well behind the lines, and not providing leadership. (Ledlie would be dismissed for his actions during the battle.)

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

The plan called for the mine to be detonated between 3:30 and 3:45 a.m. on the morning of July 30. Pleasants lit the fuse accordingly, but as with the rest of the mine's provisions, they had been given poor-quality fuses, which his men were forced to splice themselves. After more and more time passed and no explosion occurred (the impending dawn creating a threat to the men at the staging points, who were in view of the Confederate lines), two volunteers from the 48th Regiment (Lt. Jacob Douty and Sgt. Harry Reese) crawled into the tunnel. After discovering the fuse had burned out at a splice, they spliced on a length of new fuse and relit it. Finally, at 4:44 a.m., the charges exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns. A crater (still visible today) was created, long, wide, and at least deep.

The explosion immediately killed 278 Confederate soldiers of the 18th and 22nd South Carolina and the stunned Confederate troops did not direct any significant rifle or artillery fire at the enemy for at least 15 minutes. However, Ledlie's untrained division was not prepared for the explosion, and reports indicate they waited 10 minutes before leaving their own entrenchments. Footbridges were supposed to have been placed to allow them to cross their own trenches quickly. Because they were missing, however, the men had to climb into and out of their own trenches just to reach no-man's land. Once they had wandered to the crater, instead of moving around it, as the troops had been trained, they thought that it would make an excellent rifle pit in which to take cover. They therefore moved down into the crater itself, wasting valuable time and realizing too late that the crater was much too deep and exposed to function as a rifle pit and quickly becoming overcrowded while the Confederates, under Brigadier General

The plan called for the mine to be detonated between 3:30 and 3:45 a.m. on the morning of July 30. Pleasants lit the fuse accordingly, but as with the rest of the mine's provisions, they had been given poor-quality fuses, which his men were forced to splice themselves. After more and more time passed and no explosion occurred (the impending dawn creating a threat to the men at the staging points, who were in view of the Confederate lines), two volunteers from the 48th Regiment (Lt. Jacob Douty and Sgt. Harry Reese) crawled into the tunnel. After discovering the fuse had burned out at a splice, they spliced on a length of new fuse and relit it. Finally, at 4:44 a.m., the charges exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns. A crater (still visible today) was created, long, wide, and at least deep.

The explosion immediately killed 278 Confederate soldiers of the 18th and 22nd South Carolina and the stunned Confederate troops did not direct any significant rifle or artillery fire at the enemy for at least 15 minutes. However, Ledlie's untrained division was not prepared for the explosion, and reports indicate they waited 10 minutes before leaving their own entrenchments. Footbridges were supposed to have been placed to allow them to cross their own trenches quickly. Because they were missing, however, the men had to climb into and out of their own trenches just to reach no-man's land. Once they had wandered to the crater, instead of moving around it, as the troops had been trained, they thought that it would make an excellent rifle pit in which to take cover. They therefore moved down into the crater itself, wasting valuable time and realizing too late that the crater was much too deep and exposed to function as a rifle pit and quickly becoming overcrowded while the Confederates, under Brigadier General William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was an American civil engineer, railroad executive, Confederate States Army general, and Virginia politician.

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in the building of Virginia's roads and railroa ...

, gathered as many troops together as they could for a counterattack. In about an hour, they had formed up around the crater and began firing rifles and artillery down into it in what Mahone later described as a "turkey shoot

A turkey shoot is an opportunity for an individual or a party to take advantage of a situation with a significant degree of ease.

The term likely originates from a method of hunting wild turkeys in which the hunter, coming upon a flock, intention ...

."

The plan had failed, but Burnside, instead of cutting his losses, sent in Ferrero's men. Now faced with considerable flanking fire, they also descended into the crater, and for the next few hours, Mahone's soldiers, along with those of Major General Bushrod Johnson

Bushrod Rust Johnson (October 7, 1817 – September 12, 1880) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War and an officer in the United States Army. As a university professor he had been active in the state militias of Kentucky and Tenness ...

and artillery, slaughtered the IX Corps as it attempted to escape from the crater. Some Union troops eventually advanced and flanked to the right beyond the crater to the earthworks and assaulted the Confederate lines, driving the Confederates back for several hours in hand-to-hand combat. Mahone's Confederates conducted a sweep out of a sunken gully area about from the right side of the Union advance. The charge reclaimed the earthworks and drove the Union force back towards the east.

Aftermath

Union casualties were 3,798 (504 killed, 1,881 wounded, 1,413 missing or captured), Confederate 1,491 (361 killed, 727 wounded, 403 missing or captured). Many of the Union losses were suffered by Ferrero's division of the United States Colored Troops. Both black and white wounded prisoners were taken to the Confederate hospital at Poplar Lawn, in Petersburg. Meade brought charges against Burnside, and a subsequent court of inquiry censured Burnside along with Brig. Gens. Ledlie, Ferrero,Orlando B. Willcox

Orlando Bolivar Willcox (April 16, 1823 – May 11, 1907) was an American soldier who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Willcox was born in Detroit, Michigan. He entered the United States Military Ac ...

, and Col. Zenas R. Bliss. Burnside was never again assigned to duty. Although he was as responsible for the defeat as Burnside, Meade escaped immediate censure. However, in early 1865, the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War exonerated Burnside and condemned Meade for changing the plan of attack, which did little good for Burnside, whose reputation had been ruined. As for Mahone, the victory, won largely because of his efforts in supporting Johnson's stunned men, earned him a lasting reputation as one of the best young generals of Lee's army in the last years of the war.

Grant wrote to Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

, "It was the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war." He also stated to Halleck, "Such an opportunity for carrying fortifications I have never seen and do not expect again to have."

Pleasants, who had no role in the battle itself, received praise for his idea and its execution. When he was appointed a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

brigadier general on March 13, 1865, the citation made explicit mention of his role.

Grant subsequently gave in his evidence before the Committee on the Conduct of the War:

Despite the battle being a tactical Confederate victory, the strategic situation in the Eastern Theater remained unchanged. Both sides remained in their trenches, and the siege continued.

Historic site

The area of the Battle of the Crater is a frequently-visited portion of Petersburg National Battlefield Park. The mine entrance is open for inspection annually on the anniversary of the battle. There are sunken areas, where air shafts and cave-ins extend up to the "T" shape near the end. The park includes many other sites, primarily those that were a portion of the Union lines around Petersburg.

In popular culture

* The Battle of the Crater was graphically portrayed in the opening scenes of the 2003 film '' Cold Mountain'', starring Jude Law as a Confederate soldier. The film inaccurately depicts the giant explosion occurring in broad daylight; it actually happened in darkness at 4:44 A.M.References

Bibliography

* * . * * * * . * Davis, William C., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''Death in the Trenches: Grant at Petersburg''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1986. . * . * * James, Alfred P. "The Battle of the Crater." ''The Journal of the American Military History Foundation'' 2, no. 1 (Spring,1938), pp. 2–25 * Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence C. Buel, eds''Battles and Leaders of the Civil War''

4 vols. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. . * Kennedy, Frances H., ed. ''The Civil War Battlefield Guide''. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Robertson, James I., Jr., and William Pegram. '"The Boy Artillerist": Letters of Colonel William Pegram, C.S.A.

''Campaign for Petersburg'', Ch. 6 "Battle of the Crater"

for the National Park Service, 1970 * Salmon, John S. ''The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. . * * Trudeau, Noah Andre. ''The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864 – April 1865''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991. .

CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

* *Chernow, Ron

Ronald Chernow (; born March 3, 1949) is an American writer, journalist and biographer. He has written bestselling historical non-fiction biographies.

He won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Biography and the 2011 American History Book Prize for his ...

. ''Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

.'' London: Penguin Press, 2017. .

* Greene, A. Wilson. ''A Campaign of Giants: The Battle for Petersburg''. Vol. 1: ''From the Crossing of the James to the Crater''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018. .

* Levin, Kevin M. ''Remembering the Battle of the Crater: War as Murder.'' Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012. .

* Pleasants, Henry. ''Inferno at Petersburg''. Edited by George H. Straley. Philadelphia: Chilton Book Co., 1961. .

* Schmutz, John F. ''The Battle of the Crater: a Complete History''. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009.

See also

* Lochnagar mine from the Battle of the Somme in theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

External links

*Battle of the Crater in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

* ttp://www.beyondthecrater.com/siege-of-petersburg-resources/maps/petersburg-campaign-maps/third-offensive-maps/the-battle-of-the-crater-maps/ Battle of the Crater Maps {{authority control Crater Crater Crater Crater Petersburg, Virginia the Crater 1864 in Virginia July 1864 events Confederate war crimes