Battle of Ticonderoga (1758) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Carillon, also known as the 1758 Battle of Ticonderoga, Chartrand (2000), p. 57 was fought on July 8, 1758, during the

The French, who had started construction on Fort Carillon in 1755, Lonergan (1959), p. 22 used it as a launching point for the successful

The French, who had started construction on Fort Carillon in 1755, Lonergan (1959), p. 22 used it as a launching point for the successful

Montcalm arrived at Fort Carillon on June 30, and found there a significantly under-staffed garrison, with only 3,500 men, and food sufficient for only nine days. Bourlamaque's scouts reported that the British had 20,000 or more troops massing near the remains of

Montcalm arrived at Fort Carillon on June 30, and found there a significantly under-staffed garrison, with only 3,500 men, and food sufficient for only nine days. Bourlamaque's scouts reported that the British had 20,000 or more troops massing near the remains of

The British army began an unopposed landing at the north end of Lake George on the morning of July 6. Abercrombie first landed an advance force to check the area where the forces were to disembark, and found it recently deserted; some supplies and equipment had been left behind by the French in their hasty departure. The bulk of the army landed, formed into columns, and attempted to march up the west side of the stream that connected Lake George to Lake Champlain, rather than along the portage trail, whose bridges Montcalm had destroyed. However, the wood was very thick, and the columns could not be maintained. Kingsford (1890), p. 164

Near the area where Bernetz Brook enters the La Chute, Captain Trépezet and his troop, who were attempting to return to the French lines, encountered

The British army began an unopposed landing at the north end of Lake George on the morning of July 6. Abercrombie first landed an advance force to check the area where the forces were to disembark, and found it recently deserted; some supplies and equipment had been left behind by the French in their hasty departure. The bulk of the army landed, formed into columns, and attempted to march up the west side of the stream that connected Lake George to Lake Champlain, rather than along the portage trail, whose bridges Montcalm had destroyed. However, the wood was very thick, and the columns could not be maintained. Kingsford (1890), p. 164

Near the area where Bernetz Brook enters the La Chute, Captain Trépezet and his troop, who were attempting to return to the French lines, encountered

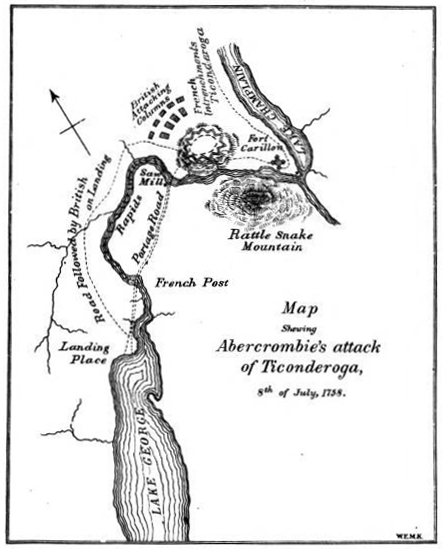

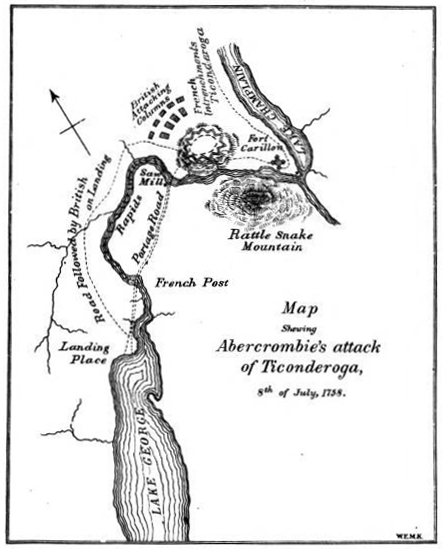

Image:CarillonBattleSmall.png, 240px, Schematic map depicting the battle lines (click for zoomable image)

desc none

default

The battle began on the morning of July 8 with

Bataille du Fort Carillon

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Carillon 1758 in New France 1758 in North America

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

(which was part of the global Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

). It was fought near Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, presently known as Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it ...

(now known as Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga (), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. It was constructed by Canadian-born French milit ...

) on the shore of Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

in the frontier

A frontier is the political and geographical area near or beyond a boundary. A frontier can also be referred to as a "front". The term came from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"—the region of a country that fronts ...

area between the British colony of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and the French colony of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

.

In the battle, which took place primarily on a rise about three-quarters of a mile (one km) from the fort itself, a French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

army of about 3,600 men under General Marquis de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

and the Chevalier de Levis defeated a numerically superior force of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

troops under General James Abercrombie, which frontally assaulted an entrenched French position without using field artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the early 20t ...

, a lack that left the British and their allies vulnerable and allowed the French to win a complete victory. The battle was the bloodiest of the American theater of the war, with over 3,000 casualties suffered. French losses were about 400, while more than 2,000 were British. Nester (2008), p. 7

American historian Lawrence Henry Gipson

Lawrence Henry Gipson (December 7, 1880 – September 26, 1971) was an American historian, who won the 1950 Bancroft Prize and the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for History for volumes of his magnum opus, the fifteen-volume history of "The British Empire Be ...

wrote of Abercrombie's campaign that "no military campaign was ever launched on American soil that involved a greater number of errors of judgment on the part of those in positions of responsibility".Gipson Gipson is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Andy Gipson (born 1976), American politician

*Charles Gipson (born 1972), American baseball player

*Fred Gipson (1908–1973), American writer

*Graham Gipson (born 1932), Australian spr ...

, p. 232 Many military historians have cited the Battle of Carillon as a classic example of tactical military incompetence

Military incompetence refers to incompetencies and failures of military organisations, whether through incompetent individuals or through a flawed institutional culture.

The effects of isolated cases of ''personal'' incompetence can be disproporti ...

. Abercrombie, confident of a quick victory, ignored several viable military options, such as flanking the French breastworks, waiting for his artillery, or laying siege to the fort. Instead, relying on a flawed report from a young military engineer

Military engineering is loosely defined as the art, science, and practice of designing and building military works and maintaining lines of military transport and military communications. Military engineers are also responsible for logistics ...

, and ignoring some of that engineer's recommendations, he decided in favor of a direct frontal assault

The military tactic of frontal assault is a direct, full-force attack on the front line of an enemy force, rather than to the flanks or rear of the enemy. It allows for a quick and decisive victory, but at the cost of subjecting the attackers to ...

on the thoroughly entrenched French, without the benefit of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

. Montcalm, while concerned about the weak military position of the fort, conducted the defense with spirit. However, due in part to a lack of time, he committed strategic errors in preparing the area's defenses that a competent attacker could have exploited, and he made tactical errors that made the attackers' job easier.

The fort, abandoned by its garrison, was captured by the British the following year, and it has been known as Fort Ticonderoga (after its location) ever since. This battle gave the fort a reputation for impregnability that had an effect on future military operations in the area. There were several large-scale military movements through the area in both the French and Indian War, as well as the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

with the American Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

The capture of Fort Ticonderoga occurred during the American Revolutionary War on May 10, 1775, when a small force of Green Mountain Boys led by Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold surprised and captured the fort's small British garrison. ...

and the British siege of the fort two years later, however this was the only major battle fought near the fort's location.

Geography

Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, presently known as Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it ...

is situated on a point of land between Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

and Lake George, at a natural point of conflict between French forces moving south from Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and the St. Lawrence River Valley across the lake toward the Hudson Valley

The Hudson Valley (also known as the Hudson River Valley) comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to ...

, and British forces moving up the Hudson from Albany. The fort was sited with Lake Champlain to the east, with Mount Independence rising on the far side. Immediately to the south of the fort lay the mouth of the La Chute River

The La Chute River, also known as Ticonderoga Creek, is a short, fast-moving river, near the Vermont–New York border. It is now almost wholly contained within the municipality of Ticonderoga, New York, connecting the northern end and outlet ...

, which drains Lake George. The river was largely non-navigable, and there was a portage

Portage or portaging (Canada: ; ) is the practice of carrying water craft or cargo over land, either around an obstacle in a river, or between two bodies of water. A path where items are regularly carried between bodies of water is also called a ...

trail from the northern end of Lake George to the location of a sawmill the French had built to assist in the fort's construction. The trail crossed the La Chute twice; once about from Lake George, and again at the sawmill, which was about from the fort.

To the north of the fort was a road going to Fort St. Frédéric

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

. To the west was a low rise of land, beyond which lay Mount Hope, a rise that commanded part of the portage trail, but was too far from the fort to pose it any danger. Lonergan (1959), p. 26 The most serious geographic defect in the fort's location was Mount Defiance (known at the time of this battle as Rattlesnake Hill, and in the 1770s as Sugar Bush), which lay to the south of the fort, across the La Chute River. This hill, which was steep and densely forested, provided an excellent firing position for cannon aimed at the fort. Anderson (2005), p. 134 Nicolas Sarrebource de Pontleroy, Montcalm's chief engineer, said of the fort's site, "Were I to be entrusted with the siege of it, I should require only six mortars and two cannon." Anderson (2005), p. 135

Background

Prior to 1758, theFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

had gone very poorly for the British, whose military met few of its objectives. Following a string of French victories in 1757 in North America, coupled with military setbacks in Europe, William Pitt gained full control of the direction of British military efforts in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

. Embarking on a strategy that emphasized defense in Europe, where France was strong, and offense in North America, where France was weak, he resolved to attack New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

(the colonial holdings of France in North America) in three strategic campaigns. Anderson (2000), pp. 213–214,232 Large-scale campaigns were planned to capture Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

on the Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

frontier and the fortress at Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour ...

(on Île-Royale, now known as Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

). The third campaign, assigned to General James Abercrombie, was to launch an attack against Canada through the Champlain Valley. Nester (2008), p. 59 Pitt probably would have preferred to have George Howe, a skilled tactician and a dynamic leader, lead this expedition, but seniority and political considerations led him to appoint the relatively undistinguished Abercrombie instead. Howe was appointed a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

, and placed as Abercrombie's second in command. Nester (2008), pp. 60, 65

The French, who had started construction on Fort Carillon in 1755, Lonergan (1959), p. 22 used it as a launching point for the successful

The French, who had started construction on Fort Carillon in 1755, Lonergan (1959), p. 22 used it as a launching point for the successful siege of Fort William Henry

The siege of Fort William Henry (3–9 August 1757, french: Bataille de Fort William Henry) was conducted by a French and Indian force led by Louis-Joseph de Montcalm against the British-held Fort William Henry. The fort, located at the south ...

in 1757. Anderson (2005), pp. 109–115 Despite that and other successes in North America in 1757, the situation did not look good for them in 1758. As early as March, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

, the commanding general responsible of the French forces in North America, and the Marquis de Vaudreuil, New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

's governor, were aware that the British were planning to send large numbers of troops against them, and that they would have relatively little support from King Louis XV of France

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

. Nester (2008), p. 92 The lack of support from France was in large part due to an unwillingness of the French military to risk the movement of significant military forces across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, which was dominated by Britain's Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Nester (2008), p. 68 This situation was further exacerbated by Canada's poor harvest in 1757, which resulted in food shortages as the winter progressed. Nester (2008), p. 58

Montcalm and Vaudreuil, who did not get along with each other, differed on how to deal with the British threat. They had fewer than 5,000 regular troops, an estimated six thousand militia men, and a limited number of Indian allies, to bring against British forces reported to number 50,000. Vaudreuil, who had limited combat experience, wanted to divide the French forces, with about 5,000 each at Carillon and Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour ...

, and then send a picked force of about 3,500 men against the British in the Mohawk River

The Mohawk River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed October 3, 2011 river in the U.S. state of New York. It is the largest tributary of the Hudson River. The Mohawk ...

on the northwestern frontiers of the Province of New York. Montcalm believed this to be folly, as the plan would enable the British to easily divert some of their forces to fend off the French attack. Nester (2008), pp. 89–90 Vaudreuil prevailed, and in June 1758 Montcalm left Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

for Carillon. Nester (2008), pp. 95–96

British preparations

The British amassed their army, under the command of General James Abercrombie, near the remains ofFort William Henry

Fort William Henry was a British fort at the southern end of Lake George, in the province of New York. The fort's construction was ordered by Sir William Johnson in September 1755, during the French and Indian War, as a staging ground for ...

, which lay at the southern end of Lake George but had been destroyed following its capture by the French the previous year. The army numbered fully 16,000 men, making it the largest single force ever deployed in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

at the time. Anderson (2005), p. 133 Its complement of 6,000 regular troops included Lord John Murray's Highlanders of the 42nd (Highland) Regiment of Foot, the 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot

The 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot was an Irish infantry regiment of the British Army, formed in 1689. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 108th (Madras Infantry) Regiment of Foot to form the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers in 188 ...

, the 44th Regiment of Foot

The 44th Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment in the British Army, raised in 1741. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot to form the Essex Regiment in 1881.

History

Early history

The regim ...

, 46th Regiment of Foot

The 46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1741. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot to form the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry in 1881, b ...

, the 55th Regiment of Foot

The 55th Regiment of Foot was a British Army infantry regiment, raised in 1755. After 1782 it had a county designation added, becoming known as the 55th (Westmorland) Regiment of Foot. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 34th (Cu ...

, the 1st and 4th battalions of 60th (Royal American) Regiment

The King's Royal Rifle Corps was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army that was originally raised in British North America as the Royal American Regiment during the phase of the Seven Years' War in North America known in the United ...

, and Gage's Light Infantry, while the provinces providing militia support included Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

, and Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

. Parkman (1884), p. 93 On July 5, 1758, these troops embarked on boats, which unloaded them at the north end of Lake George on July 6.

French defensive preparations

ColonelFrançois-Charles de Bourlamaque

François-Charles de Bourlamaque (the surname can also be seen as Burlamaqui) (1716 – 1764) was a French military leader and Governor of Guadeloupe from 1763.

Biography

His father Francesco Burlamacchi was born in Lucca, Tuscany. He began as ...

, in command of Fort Carillon prior to Montcalm's arrival, knew by June 23 that a major British offensive was about to begin. He had sent a messenger bearing a letter from Vaudreuil to Abercrombie (part of a conventional exchange of pleasantries between opposing commanders) on June 10, expecting him to return; the fact that the British held him was an indication that the messenger had probably learned too much just by being in the British camp. Bourlamaque increased scouting activities, and learned from captured British scouts the approximate size of the British force. Nester (2008), pp. 106–107

Fort William Henry

Fort William Henry was a British fort at the southern end of Lake George, in the province of New York. The fort's construction was ordered by Sir William Johnson in September 1755, during the French and Indian War, as a staging ground for ...

. Given the large force facing him and the defects of the fort's site, Montcalm opted for a strategy of defending the likely approaches to the fort. Nester (2008), p. 114 He immediately detached Bourlamaque and three battalions to occupy and fortify the river crossing on the portage trail about two miles (3.2 km) from the northern end of Lake George, about from the fort. Montcalm himself took two battalions and occupied and fortified an advance camp at the sawmill, while remaining troops were put to work preparing additional defenses outside the fort. Kingsford (1890), p. 162 He also sent word back to Montreal of the situation, requesting that, if possible, the Chevalier de Lévis and his men, be sent as reinforcement; these were troops that Vaudreuil intended for duty at the western frontier forts. Nester (2008), p. 107 Parkman (1884), p. 88 Lévis had not yet left Montreal, so Vaudreuil instead ordered him and 400 troops to Carillon. They departed Montreal on July 2. Nester (2008), p. 108

When word reached Bourlamaque on July 5 that the British fleet was coming, he sent Captain Trépezet and about 350 men to observe the fleet, and, if possible, to prevent their landing. On learning the size of the British fleet, which was reportedly "large enough to cover the face of ake George, Anderson (2005), p. 133–134 Montcalm ordered Bourlamaque to retreat. Bourlamaque, who was satisfied with his defensive situation, resisted, not withdrawing until Montcalm repeated the orders three times. Nester (2008), p. 123 Montcalm, now aware of the scope of the movement, ordered all of the troops back to Carillon, and had both bridges on the portage trail destroyed. Kingsford (1890), p. 163 These withdrawals isolated Trépezet and his men from the main body, a situation made worse for Trépezet when his Indian guides, alarmed by the size of the British fleet, abandoned him. Chartrand (2000), p. 51

Beginning on the evening of July 6, the French began to lay out entrenchments on the rise northwest of the fort, about away, that commanded the land routes to the fort. On July 7, they constructed a lengthy series of abatis

An abatis, abattis, or abbattis is a field fortification consisting of an obstacle formed (in the modern era) of the branches of trees laid in a row, with the sharpened tops directed outwards, towards the enemy. The trees are usually interlaced ...

(felled trees with sharpened branches pointed outward) below these entrenchments. By the end of that day, they had also constructed a wooden breastwork above the trenches. These hastily erected defenses, while proof against small arms fire, would have been ineffective if the British had used cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s against them.

Bernetz Brook

The British army began an unopposed landing at the north end of Lake George on the morning of July 6. Abercrombie first landed an advance force to check the area where the forces were to disembark, and found it recently deserted; some supplies and equipment had been left behind by the French in their hasty departure. The bulk of the army landed, formed into columns, and attempted to march up the west side of the stream that connected Lake George to Lake Champlain, rather than along the portage trail, whose bridges Montcalm had destroyed. However, the wood was very thick, and the columns could not be maintained. Kingsford (1890), p. 164

Near the area where Bernetz Brook enters the La Chute, Captain Trépezet and his troop, who were attempting to return to the French lines, encountered

The British army began an unopposed landing at the north end of Lake George on the morning of July 6. Abercrombie first landed an advance force to check the area where the forces were to disembark, and found it recently deserted; some supplies and equipment had been left behind by the French in their hasty departure. The bulk of the army landed, formed into columns, and attempted to march up the west side of the stream that connected Lake George to Lake Champlain, rather than along the portage trail, whose bridges Montcalm had destroyed. However, the wood was very thick, and the columns could not be maintained. Kingsford (1890), p. 164

Near the area where Bernetz Brook enters the La Chute, Captain Trépezet and his troop, who were attempting to return to the French lines, encountered Phineas Lyman

Phineas Lyman (1716–1774) was a colonial American soldier known for his service in the provincial British Army of the French and Indian War. He later led a group of New England veterans of the war to settle in the new colony of West Florida wh ...

's Connecticut regiment, sparking a skirmish in the woods. General Howe's column was near the action, so he led it in that direction. As they approached the battle scene, General Howe was hit and instantly killed by a musket ball. A column of Massachusetts provincials, also drawn to the battle, cut off the French patrol's rear. In desperate fighting, about 150 of Trepézet's men were killed, and another 150 were captured. Fifty men, including Trepézet, escaped by swimming across the La Chute. Trepézet died the next day of wounds suffered in the battle. Chartrand (2000), p. 41

Sources disagree on the number of casualties suffered. William Nester claims British casualties were light, only ten dead and six wounded, Nester (2008), p. 131 while Rene Chartrand claims that there were about 100 killed and wounded, including the loss of General Howe. Chartrand (2000), p. 86 The British, frustrated by the difficult woods, demoralized by Howe's death, and exhausted from the overnight boat ride, camped in the woods, and returned to the landing point early the next morning. Kingsford (1890), p. 168

Portage road

On July 7 Abercrombie sent Lieutenant ColonelJohn Bradstreet

Major General John Bradstreet, born Jean-Baptiste Bradstreet (21 December 1714 – 25 September 1774) was a British Army officer during King George's War, the French and Indian War, and Pontiac's War. He was born in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia ...

and a sizable force down the portage path. On reaching the first crossing, where Bourlamaque had camped, they rebuilt the bridge there, and proceeded on to the sawmill crossing. The army then followed, and set up its camp there. Scouts and prisoners reported to Abercrombie that Montcalm had 6,000 men and was expecting the Chevalier de Lévis to arrive at any moment with 3,000 reinforcements. Abercrombie ordered his engineer, Lieutenant Matthew Clerk, and one of his aides, Captain James Abercrombie (it is uncertain if the Abercrombies were related or not) to reconnoiter the French defenses. After ascending Rattlesnake Hill (as Mount Defiance was then known), they reported that the French position appeared to be incomplete, and could be "easily forced, even without cannon". Nester (2008), p. 138 They were unaware that the French had disguised much of the works with shrubs and trees, and that they were in fact largely complete. Chartrand (2000), p. 58 Clerk's report included recommendations to fortify both the summit and the base of Rattlesnake Hill. Abercrombie decided that they had to attack the next morning, hopefully before Lévis and his supposed 3,000 arrived. Lévis arrived at the fort on the evening of July 7 with his troop of 400 regulars. Parkman (1884), p. 103

Abercrombie held a war council that evening. The options he presented to his staff were limited to asking if the next day's attack should be in three ranks or four; the council opted for three. Anderson (2000), p. 243 Abercrombie's plan of attack omitted Clerk's recommendation to fortify the summit of Rattlesnake Hill; in addition to the frontal assault, 4 six-pound guns and a howitzer were to be floated down the La Chute River and mounted at the base of Rattlesnake Hill, with 20 bateaux

A bateau or batteau is a shallow-draft, flat-bottomed boat which was used extensively across North America, especially in the colonial period and in the fur trade. It was traditionally pointed at both ends but came in a wide variety of sizes. ...

of troops to support the effort. Nester (2008), p. 142

Early on the morning of July 8, Clerk went out once again to the base of Rattlesnake Hill to observe the French defenses; his report indicated that he still felt the French lines could be taken by assault. Nester (2008), p. 143

Battle lines form

Rogers' Rangers

Rogers' Rangers was a company of soldiers from the Province of New Hampshire raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Years' War ( French and Indian War). The unit was quickly adopted into the British arm ...

and light infantry from Colonel Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of t ...

's 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot pushing the few remaining French scouts behind the entrenchments. They were followed by provincials from New York and Massachusetts, and then three columns of regulars, who made their way through the provincial formations to begin the attack. The 27th and 60th made up the right column, under the command of the 27th's Lt. Col. William Haviland

William Haviland (1718 – 16 September 1784) was an Irish-born general in the British Army. He is best known for his service in North America during the Seven Years' War.

Life

William Haviland was born in Ireland in 1718. He entered milita ...

, the 44th and 55th under Lt. Col. John Donaldson made the center, and the 42nd and 46th under the 42nd's Lt. Col. Francis Grant formed the left column. Each column was preceded by the regimental light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often foug ...

companies. Held in reserve were provincial regiments from Connecticut and New Jersey. Nester (2008), p. 148 Chartrand (2000), pp. 61–62

Montcalm had organized the French forces into three brigades and a reserve. He commanded the Royal Roussillon and Berry

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit, although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples are strawberries, rasp ...

battalions in the center of the entrenchments, while Lévis commanded the Béarn

The Béarn (; ; oc, Bearn or ''Biarn''; eu, Bearno or ''Biarno''; or ''Bearnia'') is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three B ...

, Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne (, ; oc, Guiana ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the archdiocese of Bordeaux.

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transformation o ...

, and la Reine La Reine can refer to

Organizations

* Régiment de La Reine, a regiment of the French Army of the Ancien Régime

Places

* La Reine, Quebec, a municipality in Quebec, Canada

* La Reine, a populated place in the commune of Saint-Priest-des-Champs, ...

battalions on the right, and Bourlamaque led the La Sarre

La Sarre is a town in northwestern Quebec, Canada, and is the most populous town and seat of the Abitibi-Ouest Regional County Municipality. It is located at the intersection of Routes 111 and 393, on the La Sarre River, a tributary of Lake ...

and Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately ...

battalions on the left. Each battalion was given roughly of the entrenchment to defend. Redoubts with cannon protected the flanks of the entrenchments, although the one on the right had not been completed. The low ground between the left flank and the La Chute River was guarded by militia and marines, who had also constructed abatis

An abatis, abattis, or abbattis is a field fortification consisting of an obstacle formed (in the modern era) of the branches of trees laid in a row, with the sharpened tops directed outwards, towards the enemy. The trees are usually interlaced ...

to help protect their position. Reserve forces were either in the fort itself, or on the grounds between the fort and the entrenchments on Mount Hope. Portions of each battalion were also held in reserve, to assist in areas where they might be needed. Nester (2008), pp. 139–140

Battle

While Abercrombie had expected the battle to begin at 1 pm, by 12:30 elements of the New York regiments on the left began engaging the French defenders. Chartrand (2000), p. 64 The sounds of battle led Haviland to believe that the French line might have been penetrated, so he ordered his men forward, even though not all of the regulars were in place, and Abercrombie had not given an order to advance. Chartrand (2000), pp. 65, 68 The result, rather than an orderly, coordinated advance on the French position, was a piecemeal entry of the regulars into the battle. As companies of the regulars came forward, they arranged themselves into lines as instructed, and then began to advance. The right column, with a shorter distance to travel, attacked first, followed by the center, and then the left. The 42nd had initially been held in reserve, but after insisting on being allowed to participate, they joined the action. Nester (2008), pp. 151–153 The French position was such that they were able to lay down withering fire on the British forces as they advanced, and the abatis (a word that shares derivation with ''abattoir

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is no ...

'', or slaughterhouse) rapidly became a killing field. By about 2 pm, it was clear that the first wave of attack had failed. Chartrand (2000), pp. 70–71 Montcalm was active on the battlefield, having removed his coat, and was moving among his men, giving encouragement and making sure all of their needs were being met. Chartrand (2000), p. 72 Abercrombie, who was reported by early historians like Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman Jr. (September 16, 1823 – November 8, 1893) was an American historian, best known as author of '' The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life'' and his monumental seven-volume '' France and England in North Am ...

and Thomas Mante to be at the sawmill (and thus well away from the action), Parkman (1884), p. 106 Mante (2005), p. 159 was reported by his aide, James Abercrombie, to be near the rear of the lines by the La Chute River during much of the battle, Nester (2008), p. 156 and to have approached the front of the French lines at one point early in the battle. Chartrand (2000), p. 68 It is uncertain why, after the first wave of attack failed, Abercrombie persisted in ordering further attacks. Writing in his own defense, he later claimed that he was relying on Clerk's assessment that the works could be easily taken; this was clearly refuted by the failure of the first charge. Nester (2008), p. 152

Around 2 p.m., the British barges carrying artillery floated down the La Chute River, and, contrary to plan, came down a channel between an island in the La Chute and the shore. This brought them within range of the French left and some of the fort's guns. Fire from cannons on the fort's southwest bastion's sank two of the barges, spurring the remaining vessels to retreat. Chartrand (2000), pp. 71–72

Abercrombie ordered his reserves, the Connecticut and New Jersey provincials, into the battle around 2, but by 2:30 it was clear their attack also failed. Abercrombie then tried to recall the troops, but a significant number, notably the 42nd and 46th regiments on the British left, persisted in the attack. Around 5 pm the 42nd made a desperate advance that actually succeeded in reaching the base of the French wall; those that actually managed to scale the breastwork were bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

ed. Chartrand (2000), pp. 76–80 One British observer noted that "Our Forces Fell Exceeding Fast", while another wrote that they were "Cut Down Like Grass". Anderson (2000), p. 244 The slaughter went on until nightfall, with a great many men retreating behind a breastwork that had been erected at the back of the battlefield. Anderson (2000), p. 246

Finally realizing the scope of the disaster, Abercrombie ordered the troops to muster and march down to the landing on Lake George. The retreat in the dark woods became somewhat panicked and disorganized, as rumors of French attacks swirled among the troops. By dawn the next morning, the army was rowing back up Lake George, reaching its base at the southern end around sunset. The humiliating nature of the retreat was immediately apparent to some of its participants; Lieutenant Colonel Artemas Ward

Artemas Ward (November 26, 1727 – October 28, 1800) was an American major general in the American Revolutionary War and a Congressman from Massachusetts. He was considered an effective political leader, President John Adams describing him as ...

wrote that they "shamefully retreated". Anderson (2000), p. 247

Aftermath

Montcalm, wary of a second British attack, and concerned about the fatigue of his troops after a long day of battle, had barrels of beer and wine brought forward to the lines. The troops spent the night alternating between sleeping and working on the defenses in anticipation of a renewed attack. Nester (2008), p. 157 News of the battle was received in England shortly after news of the fall of Louisbourg, putting a damper on the celebrations marking that victory. The full scope of British victories in 1758 did not reach English shores until later in the year, when Pitt learned of the successes at Forts Duquesne and Frontenac, key steps in completing the conquest of New France. Anderson (2000), p. 298 Had Carillon also fallen in 1758, the conquest might have been completed in 1758 or 1759; Nester (2008), p. 206 as it happened, Montreal (the last point of resistance) did not surrender until 1760, with campaigns launched fromFort Oswego

Fort Oswego was an 18th-century trading post in the Great Lakes region in North America, which became the site of a battle between French and British forces in 1756 during the French and Indian War. The fort was established in 1727 on the orders o ...

, Quebec, and Carillon, which was captured and renamed Ticonderoga in 1759 by forces under the command of Jeffery Amherst, the victor at Louisbourg.See e.g. Anderson (2000), pp. 312ff, for details on the remainder of the war.

Abercrombie never led another military campaign. Although he was active at Lake George, he did little more than provide support for John Bradstreet's successful attack on Fort Frontenac, which was authorized in a war council on July 13. Bradstreet left with 3,000 men on July 23, and Abercrombie then refused to engage in further offensive acts, alleging a shortage of manpower. Nester (2008), p. 168 William Pitt, the British Secretary of State who had designed the British military strategy and received word of the defeat in August, wrote to Abercrombie on September 18 that the "King has judged proper that you should return to England." Nester (2008), p. 204 Abercrombie continued to be promoted, eventually reaching the rank of full General in 1772.

The fact that Indians allied to the British witnessed the debacle first hand complicated future relations with them. News of the defeat circulated widely in their communities, which had a significant effect on the ability of British agents to recruit Indians to their side for future operations. Nester (2008), p. 147

Casualties

The battle was the bloodiest of the war, with over 3,000 casualties suffered. French casualties are normally considered to be comparatively light: 104 killed and 273 wounded in the main battle. Combined with the effective elimination of Trépezet's force on July 6, there were about 550 casualties, about 13 percent of the French force, a percentage similar to the losses of the British (who Chartrand calculates as having lost 11.5 to 15 percent). Chartrand (2000), p. 88 General Abercrombie reported 547 killed, 1,356 wounded, and 77 missing. Lévis in one report claimed that the French recovered 800 British bodies, implying that Abercrombie may have underreported the actual death toll. Chartrand estimates the number of British killed (or died of their wounds) at about 1,000 for the main battle, with about 1,500 wounded. The skirmish on July 6 cost the British about 100 killed and wounded, and the loss of General Howe. The 42nd Regiment, known as theBlack Watch

The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion, Royal Regiment of Scotland (3 SCOTS) is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. The regiment was created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881, when the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regime ...

, paid dearly with the loss of many lives and many severely wounded. More than 300 men (including 8 officers) were killed, and a similar number were wounded, representing a significant fraction of the total casualties suffered by the British. Stewart (1825), pp. 315–316 King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

, later in July 1758, designated the 42nd a "Royal" regiment, due to its gallantry in earlier battles, and issued letters of service for adding a second battalion "as a testimony of his Majesty's satisfaction and approbation of the extraordinary courage, loyalty, and exemplary conduct of the Highland regiment." Stewart (1825), pp. 317–318 However, the king did not learn of the regiment's loss of almost half its strength in this battle until August. Nester (2008), p. 46

A legend has long circulated concerning the death of the Black Watch's Major Duncan Campbell. In 1742, the ghost of Campbell's dead brother is said to have appeared to him in a dream with a promise to meet him again at "Ticonderoga", a place name that was unknown to him at the time. Campbell died of wounds sustained during the battle. Lonergan (1959), pp. 47–53

Analysis

The actions of both commanders have been extensively analyzed in this action. While Montcalm performed well during the battle, some tactical options escaped his notice, and some of his actions in preparing the defenses at Carillon are open to question. In contrast, almost everything Abercrombie did has been questioned. It is widely held among historians that he was an incompetent commander. Nester (2008), pp. 162–164 lists a variety of historically critical sources, and also rebuts a number of attempted defenses of Abercrombie. Anderson (2005), p. 172, calls Abercrombie "the least competent officer ever to serve as British commander in chief in America"Montcalm

Both commanders were a product of the environment of European warfare, which generally took place in open fields with relatively easy mobility, and were thus uncomfortable with woodland warfare. Neither liked the irregular warfare practiced by the Indians and British counterparts likeRogers' Rangers

Rogers' Rangers was a company of soldiers from the Province of New Hampshire raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Years' War ( French and Indian War). The unit was quickly adopted into the British arm ...

, but saw them as a necessary evil, given the operating environment. Chartrand (2000), p. 20 Although the French depended on Indian support to increase their comparatively small numbers throughout the war, Indian forces were quite low in this battle, and Montcalm generally disliked them and their practices. Nester (2008), p. 159 Chartrand (2000), pp. 25, 50

Montcalm in particular would have benefited from practicing a more irregular form of warfare. He apparently never inspected the landing area at the north end of Lake George, which was a location from which he could contest the British landing. Furthermore, the French could then have used the confined woodlands to blunt the numerical advantage of the British, and contested the entire portage road. The fact that fortifications were built along the portage road but then abandoned by the French is one indication of this failure of strategic thinking. Nester estimates that contesting the first crossing on the portage road would have gained Montcalm an additional day for defensive preparations. Nester (2008), pp. 117–118

Abercrombie

James Holden, writing in 1911, noted that American and British writers, both contemporary and historical, used words like "imbecile", "coward", "unready", and "old woman" to describe Abercrombie. Holden (1911), p. 69Before the battle

Criticisms of Abercrombie begin with his reliance on relatively poor intelligence. Reports reached him that the French strength at Carillon was 6,000, and that a further 3,000 were expected. Many of these reports were from French deserters or captives, and Abercrombie should have investigated them by sending out scouts or light infantry. Even if the reports were accurate, Abercrombie's army still significantly outnumbered that of Montcalm. The same sources must also have reported the shortage of provisions at the fort, a sign that a siege would have ended quickly. Nester (2008), p. 146 Abercrombie's next error was an apparent over-reliance on the analysis of Matthew Clerk. His lack of experienced engineers caused the state of French defences to be repeatedly misread. Nester (2008), p. 145 What is clear is that Abercrombie, in his stated desire for haste, did not want to act on Clerk's recommendation to fortify Rattlesnake Hill, and then sought to blame Clerk, claiming he was merely acting on the engineer's advice. Clerk was one of the battle's casualties, so he was unavailable to defend himself against assignment of some of the blame. Nester (2008), p. 144 Captain Charles Lee of the44th Foot

The 44th Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment in the British Army, raised in 1741. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot to form the Essex Regiment in 1881.

History

Early history

The regimen ...

wrote, on the prospect of using cannon on Rattlesnake Hill, "There was one hill in particular, which seem'd to offer itself as an ally to us, it immediately commanded the lines from hence two small cannon well planted must have drove the French in a very short time from their breast work ..this was never thought of, which (one wou'd imagine) must have occur'd to any blockhead who was not absolutely so far sunk into Idiotism as to be oblig'd to wear a bib and bells." Anderson (2000), pp. 247–248

The tactical decision not to bring cannons forward was probably one of Abercrombie's most significant errors. The use of cannon against the French works would have cleared paths through the abatis and breached the breastworks.

Abercrombie also had the option to avoid a pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

, instead beginning siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

operations against the French position. His force was large enough that he could have fully invested

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing is ...

the French position and fended off any arriving reinforcements.

Tactics

Abercrombie made two notable errors of judgment during the battle. One was a failure to recognize after the first wave of attacks that his chosen method of attack was unlikely to work. Instead of ordering additional waves of troops to the slaughter, he should have retreated to a safe distance and considered alternative actions. The second failure was that he apparently never considered ordering a flanking maneuver against the French right. At a minimum this would have stretched the French defenses, allowing his attackers elsewhere to find weak points. In fact, the French twice in the battle sent companies of militia out of their works on the right toenfilade

Enfilade and defilade are concepts in military tactics used to describe a military formation's exposure to enemy fire. A formation or position is "in enfilade" if weapon fire can be directed along its longest axis. A unit or position is "in de ...

the British attackers. Nester (2008), pp. 152–153

After the battle

The disorganized nature of the British retreat demonstrated a loss of effective command. An experienced commander could easily have encamped at the Lake George landing, taken stock of the situation, and begun siege operations against the French. Abercrombie, to the surprise of some in his army, ordered a retreat all the way back to the south end of Lake George. Nester, unable to find other rational reasons for this, claims that the general must have panicked.Legacy

While the fort itself was never endangered by the British assault, Ticonderoga became a byword for impregnability. Even though the fort was effectively handed to the British by a retreating French army in 1759, future defenders of the fort and their superior officers, who may not have been familiar with the site's shortcomings, fell under the spell of this idea. In 1777, when GeneralJohn Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British general, dramatist and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several bat ...

advanced down Lake Champlain at the beginning of the Saratoga campaign

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was an attempt by the British high command for North America to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the American Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of the British ...

, General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, who had never seen the fort, thought highly of its defensive value. Furneaux (1971), p. 51 Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

, who was at Fort Ticonderoga preparing its defenses before Burgoyne's arrival, wrote to Washington that the fort "can never be carried, without much loss of blood". Furneaux (1971), p. 58 Fort Ticonderoga was surrendered by the Americans without much of a fight in July 1777. Furneaux (1971), pp. 65–74

The modern flag of Quebec

The flag of Quebec, called the (), represents the Canadian province of Quebec. It consists of a white cross on a blue background, with four white fleurs-de-lis.

It was the first provincial flag officially adopted in Canada and was originally sh ...

is based upon a banner reputedly carried by the victorious French forces at Carillon. Emblems of Quebec The banner, now known as the flag of Carillon

The flag of Carillon was flown by the troops of General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm during the Battle of Carillon, which was fought by the French and Canadian forces against those of the British in July 1758 at Fort Carillon.

In 2009, it was displa ...

, dates back to the 17th century, confirmed by textile expert Jean-Michel Tuchscherer: "The flag is without doubt an exceptional piece of document from the 17th century". As for the coat of arm under the madonna now erased, they were most probably that of Charles, Marquis of Beauharnois (1671–1749), Governor of New France from 1726 to 1747: Silver on one side with a saber, mounted on three merlettes. Only the governor had the right to inscribe his personal crest on a banner with the arms of France, and only Beauharnois had the eagles to support his crest. The flag was probably fabricated around 1726, date of the arrival of Marquis de Beauharnois, and May 29, 1732, date when it was flown for the order of Saint Louis, with its motto: ''Bellicae virtutis praemium''. However, historian Alistair Fraser is of the opinion that stories of the flag's presence on the battlefield appear to be a 19th-century fabrication, as there is no evidence that the large religious banner (2 by 3 meters, or 6 by 10 feet) on which the flag design was based was actually used as a standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object th ...

at the battle.

Cultural references

A song called "Piper's Refrain" by Rich Nardin is based on the legend of a Scottish Highlander soldier, Duncan Campbell, who is doomed to die "at a place where he never had been" called Ticonderoga. He is a member of the Highland brigade and dies in the attack on the fort. There is another song by Margaret MacArthur on the same subject. The Nardin song was recorded by Gordon Bok, Anne Mayo Muir, and Ed Trickett on their album, ''And So Will We Yet''. The battle is also described, with some historical accuracy, in James Fenimore Cooper's 1845 novel '' Satanstoe''.Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * This work includes a printing of Abercrombie's dispatch describing the battle. * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

Bataille du Fort Carillon

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Carillon 1758 in New France 1758 in North America

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoni ...