Battle of Newburn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Newburn, also known as The Battle of Newburn Ford, took place on 28 August 1640, during the

Since Conway had insufficient men to adequately hold Newcastle and provide a large enough field army to confront Leslie, he left the town with a skeleton garrison and positioned most of his troops near

Since Conway had insufficient men to adequately hold Newcastle and provide a large enough field army to confront Leslie, he left the town with a skeleton garrison and positioned most of his troops near  The battle started around 13:00 when a Scots officer who came too close to the ford was shot, initiating an outbreak of musket fire. Around 300 Covenanter cavalry attempted to cross the river but came under concentrated fire from Lunsford's infantry and retreated. Hamilton's artillery now began an intense bombardment of the hastily prepared defences around the ford, which they soon dismantled; despite Lunsford's efforts to rally them, his troops abandoned their positions, allowing the Scots to cross. A counter-attack by the English cavalry was initially successful, but they were driven back, and their commander Henry Wilmot captured.

Since his cavalry and infantry withdrew in opposite directions, Conway was unable to reform his lines, and by early evening, the English were in full retreat towards Newcastle. One of the few members of the English army to emerge with any credit from the battle was

The battle started around 13:00 when a Scots officer who came too close to the ford was shot, initiating an outbreak of musket fire. Around 300 Covenanter cavalry attempted to cross the river but came under concentrated fire from Lunsford's infantry and retreated. Hamilton's artillery now began an intense bombardment of the hastily prepared defences around the ford, which they soon dismantled; despite Lunsford's efforts to rally them, his troops abandoned their positions, allowing the Scots to cross. A counter-attack by the English cavalry was initially successful, but they were driven back, and their commander Henry Wilmot captured.

Since his cavalry and infantry withdrew in opposite directions, Conway was unable to reform his lines, and by early evening, the English were in full retreat towards Newcastle. One of the few members of the English army to emerge with any credit from the battle was

While defeat forced Charles to call a Parliament he could not get rid of, the

While defeat forced Charles to call a Parliament he could not get rid of, the

Second Bishops' War

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

. It was fought at Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

, just outside Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

, where a ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

crossed the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wat ...

. A Scottish Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

army of 20,000 under Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (15804 April 1661) was a Scottish soldier in Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland bec ...

defeated an English force of 5,000, led by Lord Conway.

The only significant military action of the war, victory enabled the Scots to take Newcastle, which provided the bulk of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

's coal supplies, and allowed them to put pressure on the central government. The October 1640 Treaty of Ripon

The Treaty of Ripon was an agreement signed by Charles I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and the Scottish Covenanters on 28 October 1640, in the aftermath of the Second Bishops' War.

The Bishops' Wars were fought by the Covenanters to ...

agreed the Covenanter army could occupy large parts of northern England, while receiving £850 per day to cover their costs. The Scots insisted Charles recall Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

to ratify the peace settlement; he did so in November 1640, a key element in the events leading to the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Angl ...

in August 1642.

Background

TheProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

created a Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

, or 'kirk', Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

in structure, and Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

in doctrine. Presbyterian churches were ruled by Elders, nominated by congregations; Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

were governed by bishops, appointed by the monarch. In 1584, bishops were imposed on the kirk against considerable resistance; since they also sat in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

and usually supported Royal policies, arguments over their role were as much about politics as religion.

The vast majority of Scots, whether Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

or Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

, believed a 'well-ordered' monarchy was divinely mandated; they disagreed on what 'well-ordered' meant, and who held ultimate authority in clerical affairs. Royalists generally emphasised the role of the monarch more than Covenanters, but there were many factors, including nationalist allegiance to the kirk, and individual motives were very complex. Montrose fought for the Covenant in 1639 and 1640, then became a Royalist, and switching sides was common throughout the period.

When James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

succeeded as king of England in 1603, he viewed a unified Church of Scotland and England as the first step in creating a centralised, Unionist state. However, the two churches were very different in doctrine; even Scottish bishops violently opposed many Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

practices. Widespread hostility to reforms imposed on the kirk by Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

led to the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' The Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on the church ...

on 28 February 1638. Its signatories vowed to oppose any changes, and included Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

and six other members of the Scottish Privy Council

The Privy Council of Scotland ( — 1 May 1708) was a body that advised the Scottish monarch. In the range of its functions the council was often more important than the Estates in the running the country. Its registers include a wide range of ...

; in December, bishops were expelled from the kirk.

Charles resorted to military action to assert his authority, resulting in the First Bishops' War

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in 1639. His chief Scottish advisor James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton, KG, PC (19 June 1606 – 9 March 1649), known as The 3rd Marquess of Hamilton from March 1625 until April 1643, was a Scottish nobleman and influential political and military leader during the Thirty Year ...

proposed an ambitious three part strategy, in which Scottish Royalists would be supported by additional troops from England and Ireland. However, Charles' suspension of the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advise ...

during the period of Personal Rule

The Personal Rule (also known as the Eleven Years' Tyranny) was the period from 1629 to 1640, when King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland ruled without recourse to Parliament. The King claimed that he was entitled to do this under the Roya ...

from 1629 to 1640 meant there was insufficient support or money to conduct such operations, which largely failed to materialise. This allowed the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

s to consolidate their domestic position by defeating Royalist forces in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially different boundaries. The Aberdeenshire Council area inclu ...

, while the chaotic state of the English army left them unable to mount any effective opposition.

While the two sides agreed the Treaty of Berwick in June, both saw it primarily as an opportunity to strengthen their position. In April 1640, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

was recalled for the first time in eleven years but when it refused to vote taxes without concessions, it was dissolved after only three weeks. Despite this, Charles went ahead, supported by his most capable advisor, the Earl of Strafford. As in 1639, he planned an ambitious three-part attack; an Irish army from the west, an amphibious landing in the north, supported by an English attack from the south.

Once again, the first two parts failed, while his English troops consisted largely of militia levied in the south, poorly-equipped, unpaid, and unenthusiastic about the war. On the march north, lack of supplies meant they looted the areas they passed through, creating widespread disorder; several units murdered officers suspected of being Catholics, before deserting. Lacking reliable troops, Lord Conway, commander in the north, assumed a defensive posture and focused on reinforcing Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census re ...

, the usual starting point for invading England. On 17 August, cavalry units under Montrose crossed the River Tweed

The River Tweed, or Tweed Water ( gd, Abhainn Thuaidh, sco, Watter o Tweid, cy, Tuedd), is a river long that flows east across the Border region in Scotland and northern England. Tweed cloth derives its name from its association with the R ...

, followed by the rest of Leslie's army of around 20,000. The Scots bypassed the town, and headed for Newcastle-on-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is als ...

, centre of the coal trade with London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, and a valuable bargaining point.

Battle

Since Conway had insufficient men to adequately hold Newcastle and provide a large enough field army to confront Leslie, he left the town with a skeleton garrison and positioned most of his troops near

Since Conway had insufficient men to adequately hold Newcastle and provide a large enough field army to confront Leslie, he left the town with a skeleton garrison and positioned most of his troops near Hexham

Hexham ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, on the south bank of the River Tyne, formed by the confluence of the North Tyne and the South Tyne at Warden nearby, and close to Hadrian's Wall. Hexham was the administra ...

, gambling on the Scots crossing the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wat ...

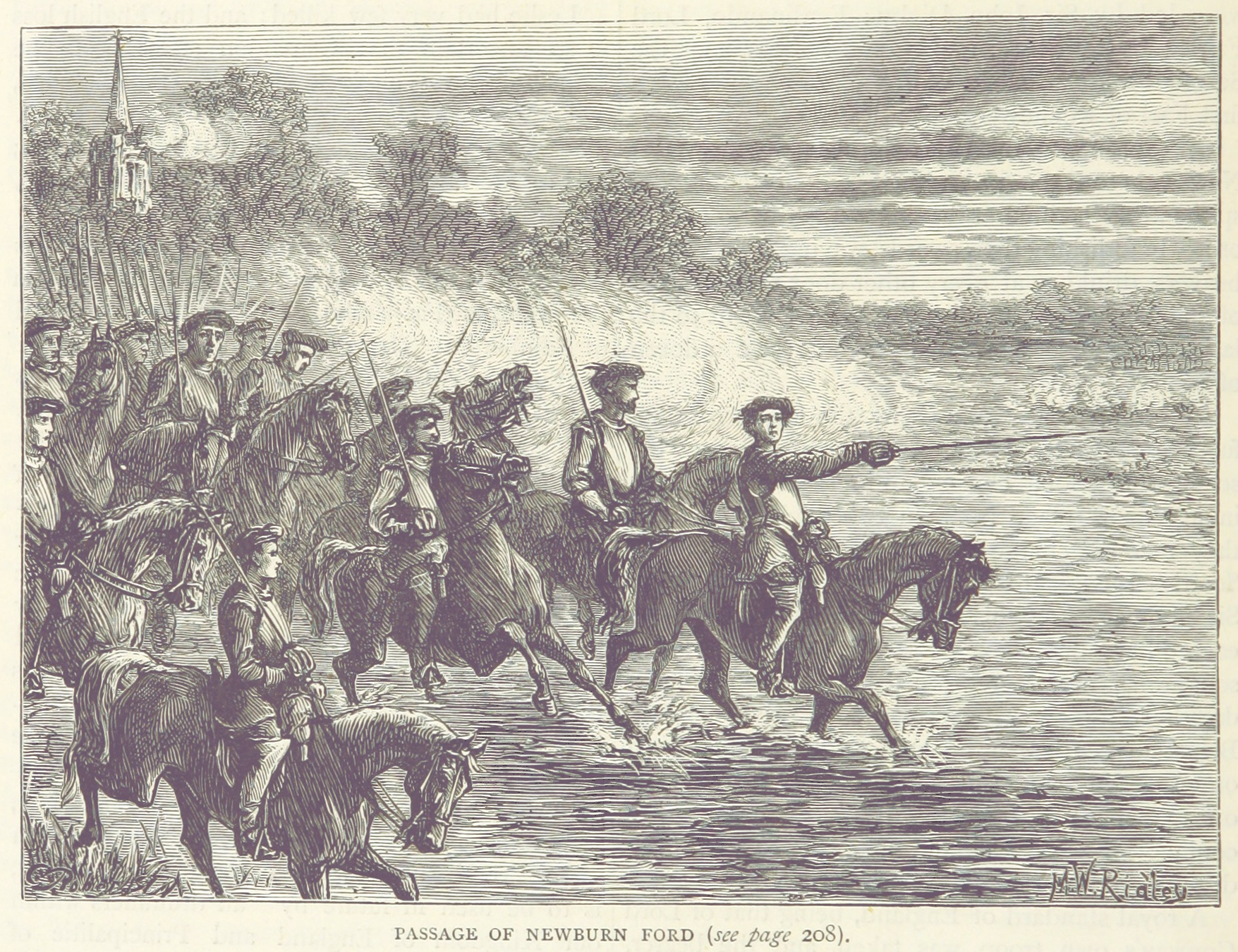

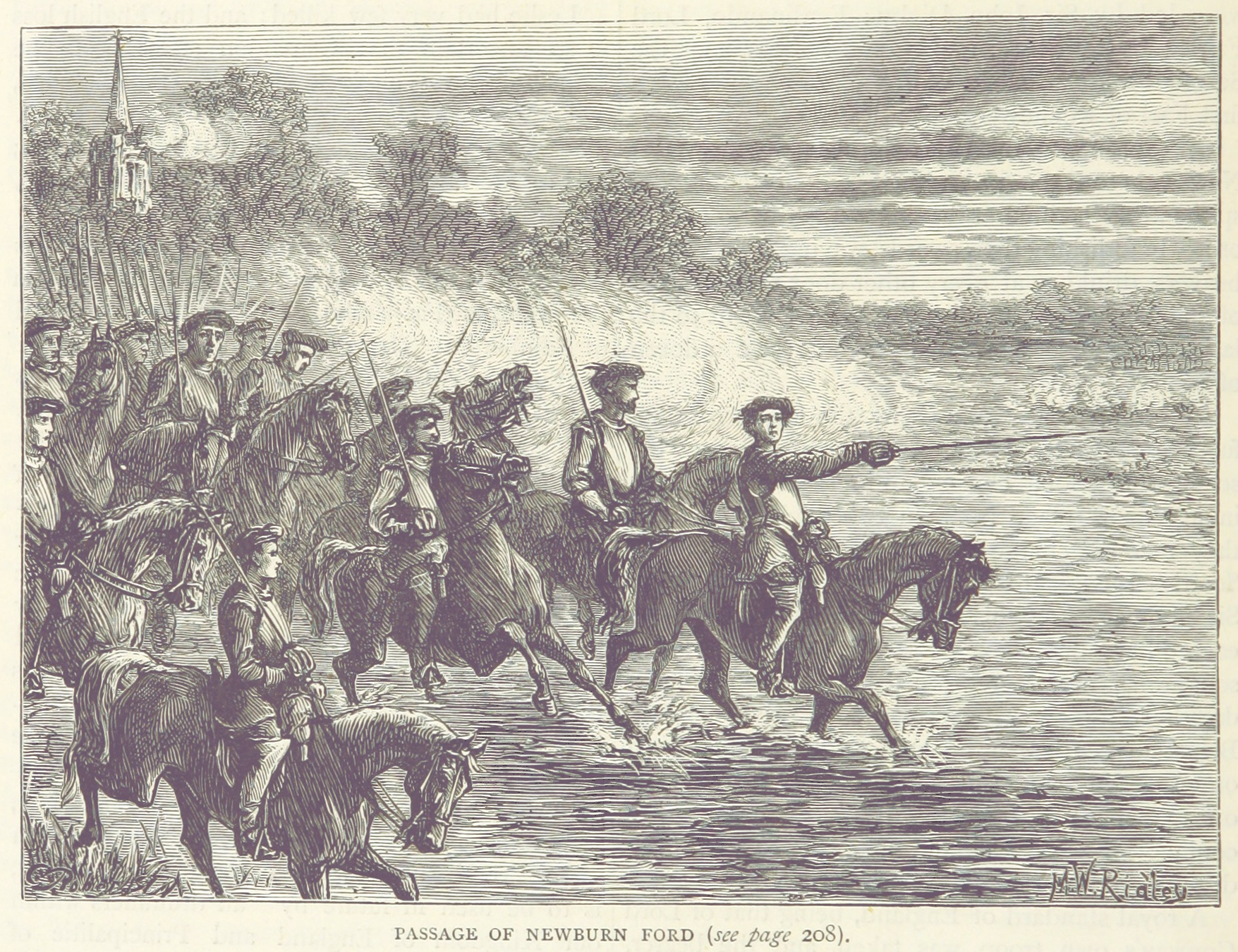

there. By 27 August, the Scots were approaching Newcastle; supplying such a large army meant Leslie either had to capture it, or retreat. Given the strong defences north of the river, he decided to cross the Tyne at Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

, then a small village six miles outside Newcastle, which would allow him to attack its weaker, southern side.

On the evening of 27 August, Conway arrived at Newburn with 1,000 cavalry and 2,000 infantry, who began building defences on the south bank of the Tyne, supervised by Colonel Thomas Lunsford

Sir Thomas Lunsford (c. 1610 – c. 1653) was a Royalist colonel in the English Civil War.

Family

Lunsford was son of Thomas Lunsford of Wilegh, Sussex. His mother, Katherine, was daughter of Thomas Fludd, treasurer of war to Queen Elizabeth, ...

. They were joined next morning by Sir Jacob Astley, with another 2,000 infantry, but in addition to being heavily outnumbered, their positions around the ford were almost indefensible. Leslie's artillery commander, Alexander Hamilton, was an extremely experienced soldier, who placed his guns on high ground to the north; this provided a clear field of fire on the English troops below, while making them almost impervious to return fire.

In addition, most of the English artillery was still at Hexham, leaving them only eight light guns with which to reply to the Scottish batteries. Sir Jacob, also a veteran of the Thirty Years War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

, suggested neutralising this disadvantage by withdrawing into the woods further back, but this advice was rejected. While waiting for low tide, Leslie asked Conway to allow his army across to 'deliver a petition to the king', which was refused; Conway then received instructions from Strafford, ordering him to prevent a crossing of the ford. In retrospect, retreat might have been a better option; taking Newcastle would have taken time, and English prisoners later reported the Scots had only enough rations for three days.

The battle started around 13:00 when a Scots officer who came too close to the ford was shot, initiating an outbreak of musket fire. Around 300 Covenanter cavalry attempted to cross the river but came under concentrated fire from Lunsford's infantry and retreated. Hamilton's artillery now began an intense bombardment of the hastily prepared defences around the ford, which they soon dismantled; despite Lunsford's efforts to rally them, his troops abandoned their positions, allowing the Scots to cross. A counter-attack by the English cavalry was initially successful, but they were driven back, and their commander Henry Wilmot captured.

Since his cavalry and infantry withdrew in opposite directions, Conway was unable to reform his lines, and by early evening, the English were in full retreat towards Newcastle. One of the few members of the English army to emerge with any credit from the battle was

The battle started around 13:00 when a Scots officer who came too close to the ford was shot, initiating an outbreak of musket fire. Around 300 Covenanter cavalry attempted to cross the river but came under concentrated fire from Lunsford's infantry and retreated. Hamilton's artillery now began an intense bombardment of the hastily prepared defences around the ford, which they soon dismantled; despite Lunsford's efforts to rally them, his troops abandoned their positions, allowing the Scots to cross. A counter-attack by the English cavalry was initially successful, but they were driven back, and their commander Henry Wilmot captured.

Since his cavalry and infantry withdrew in opposite directions, Conway was unable to reform his lines, and by early evening, the English were in full retreat towards Newcastle. One of the few members of the English army to emerge with any credit from the battle was George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

, who managed to ensure their artillery escaped intact. Both sides suffered around 300 casualties, and Leslie ordered his troops to refrain from pursuit; already in secret contact with John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

and the Parliamentary opposition, the Scots wanted to avoid making it harder to agree terms.

Aftermath

Despite this victory, the Scots still had to take Newcastle, but to Leslie's surprise, when they arrived on 30 August, Conway had withdrawn toDurham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

. One suggestion is he did not trust his ill-disciplined and mutinous troops, but morale in the rest of the army now collapsed, forcing Charles to make peace. Under the October Treaty of Ripon

The Treaty of Ripon was an agreement signed by Charles I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and the Scottish Covenanters on 28 October 1640, in the aftermath of the Second Bishops' War.

The Bishops' Wars were fought by the Covenanters to ...

, the Scots were paid £850 per day, and allowed to occupy Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

and County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

pending final resolution of terms. Funding this required the recall of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, and the Scots finally evacuated Northern England after the August 1641 Treaty of London.

While defeat forced Charles to call a Parliament he could not get rid of, the

While defeat forced Charles to call a Parliament he could not get rid of, the Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantat ...

was arguably more significant in the struggle that led to war in August 1642. Although both sides agreed on the need to suppress the revolt, neither trusted the other with control of the army raised to do so, and it was this tension that was the proximate cause of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Angl ...

.

Victory confirmed Covenanter control of government and kirk, and Scottish policy now focused on securing these achievements. The 1643 Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1 ...

was driven by concern over the implications for Scotland if Parliament were defeated; like Charles, the Covenanters sought political power through the creation of a unified church of Scotland and England, only one that was Presbyterian, rather than Episcopalian.

However, ease of victory in the Bishops' Wars meant they overestimated their military capacity and ability to enforce this objective. Unlike Scotland, Presbyterians were a minority within the Church of England, while religious Independents opposed any state church, let alone one dictated by the Scots. One of the most prominent opponents was Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, who claimed he would fight, rather than agree to such an outcome.

Many of the political radicals known as the Levellers, and much of the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

, belonged to Independent congregations; by 1646, the Scots and their English allies viewed them as a greater threat than Charles. Defeat in the 1648 Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641–1653 Irish Confed ...

resulted in his execution; failure to restore his son in the 1651 Third English Civil War

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hi ...

was followed by Scotland's incorporation into the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

, a union made on English terms.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Authority controlNewburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

1640 in England

1640 in Scotland

Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

Newburn

Newburn is a semi rural parish, former electoral ward and former urban district in western Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated ...

17th century in Northumberland