Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a minor conflict of the

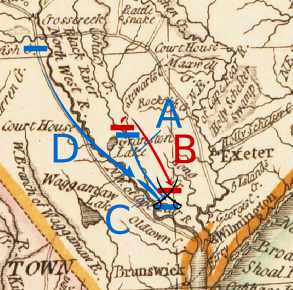

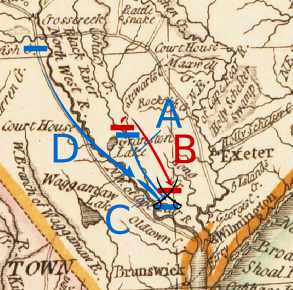

Moore led 650 Patriot militiamen out of Wilmington with the objective of preventing the loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped on the southern shore of Rockfish Creek on February 15, about from the loyalist camp. General MacDonald learned of their arrival, and sent Colonel Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on all Patriots to lay down their arms. Colonel Moore responded with his own call that the loyalists lay down ''their'' arms and support the cause of Congress. In the meantime, Caswell led 800

Moore led 650 Patriot militiamen out of Wilmington with the objective of preventing the loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped on the southern shore of Rockfish Creek on February 15, about from the loyalist camp. General MacDonald learned of their arrival, and sent Colonel Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on all Patriots to lay down their arms. Colonel Moore responded with his own call that the loyalists lay down ''their'' arms and support the cause of Congress. In the meantime, Caswell led 800

Caswell had thrown up some entrenchments on the west side of the bridge, but these were not located to patriot advantage. Their position required the patriots to defend a position whose only line of retreat was across the narrow bridge, a distinct disadvantage that MacDonald recognized when he saw the plans.Wilson, p. 27 In a council held that night, the loyalists decided to attack, since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area. During the night, Caswell decided to abandon that position and instead take up a position on the far side of the creek. To further complicate the loyalists' use of the bridge, the militia took up its planking and greased the support rails.Wilson, p. 28

Caswell had thrown up some entrenchments on the west side of the bridge, but these were not located to patriot advantage. Their position required the patriots to defend a position whose only line of retreat was across the narrow bridge, a distinct disadvantage that MacDonald recognized when he saw the plans.Wilson, p. 27 In a council held that night, the loyalists decided to attack, since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area. During the night, Caswell decided to abandon that position and instead take up a position on the far side of the creek. To further complicate the loyalists' use of the bridge, the militia took up its planking and greased the support rails.Wilson, p. 28

"The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge," ''Revolutionary North Carolina''

a digital textbook produced by the UNC School of Education. {{DEFAULTSORT:Moore's Creek Bridge, Battle of 1776 in North Carolina Moore's Creek Bridge Battles involving Great Britain Battles involving the United States Moore's Creek Bridge Moore's Creek Bridge February 1776 events Last stands Pender County, North Carolina Scottish-American culture in North Carolina Scottish-American history

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

fought near Wilmington (present-day Pender County), North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and S ...

, on February 27, 1776. The victory of the North Carolina Provincial Congress

The North Carolina Provincial Congresses were extra-legal unicameral legislative bodies formed in 1774 through 1776 by the people of the Province of North Carolina, independent of the British colonial government. There were five congresses. They ...

' militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

force over British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

governor Josiah Martin

Josiah Martin (23 April 1737 – 13 April 1786) was a British Army officer and colonial official who served as the ninth and last British governor of North Carolina from 1771 to 1776.

Early life and career

Martin was born in Dublin, Ireland, o ...

's and Tristan Worsley's reinforcements at Moore's Creek marked the decisive turning point of the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

in North Carolina. American independence

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

would be declared less than five months later.

Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

recruitment efforts in the interior of North Carolina began in earnest with news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and patriots in the province also began organizing Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

and militia. When word arrived in January 1776 of a planned British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

expedition to the area, Martin ordered his militia to muster in anticipation of their arrival. Revolutionary militia and Continental units mobilized to prevent the junction, blockading several routes until the poorly armed loyalists were forced to confront them at Moore's Creek Bridge, about north of Wilmington.

In a brief early-morning engagement, a Highland charge across the bridge by sword-wielding loyalists shouting in Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

was met by a barrage of musket and artillery fire. Two loyalist leaders were killed, another captured, and the whole force was scattered. In the following days, many loyalists were arrested, putting a damper on further recruiting efforts. North Carolina was not militarily threatened again until 1780, and memories of the battle and its aftermath negated efforts by Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

to recruit loyalists in the area in 1781.

Background

British recruiting

In early 1775, with political and military tensions rising in theThirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centuri ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and S ...

's royal governor, Josiah Martin

Josiah Martin (23 April 1737 – 13 April 1786) was a British Army officer and colonial official who served as the ninth and last British governor of North Carolina from 1771 to 1776.

Early life and career

Martin was born in Dublin, Ireland, o ...

, hoped to combine the recruiting of Scots Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

in the North Carolina interior with that of sympathetic former Regulators

Regulator may refer to:

Technology

* Regulator (automatic control), a device that maintains a designated characteristic, as in:

** Battery regulator

** Pressure regulator

** Diving regulator

** Voltage regulator

* Regulator (sewer), a control dev ...

(a group originally opposed to corrupt colonial administration) and disaffected loyalists in the coastal areas to build a large loyalist force to counteract patriot sympathies in the province.Russell, p. 79 His petition to London to recruit an army of 1,000 men had been rejected, but he continued efforts to rally loyalist support.

At about the same time, Allan Maclean of Torloisk

Allan Maclean of Torloisk (1725–1798) was a Jacobite who became a British Army general. He was born on the Isle of Mull, Scotland. He is best known for leading the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) in the Battle of Quebec.

...

, despite having fought for Prince Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (20 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, grandson of James II and VII, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, Scotland and ...

during the Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took p ...

, petitioned King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Bri ...

for permission to recruit Scottish Loyalists throughout North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the C ...

. In April, he received royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

to recruit a regiment to be known as the Royal Highland Emigrants from demobilized veterans of the Highland regiments

A Scottish regiment is any regiment (or similar military unit) that at some time in its history has or had a name that referred to Scotland or some part thereof, and adopted items of Scottish dress. These regiments were created after the Acts ...

now living as settlers in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

. One battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

was to be recruited in the northern provinces, including New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* ...

, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen ...

and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Engl ...

, while a second battalion was to be raised in North Carolina and other southern Colonies, where a large number of Highland soldiers had been given land grants. After receiving his commissions from General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of th ...

in June, Maclean of Torloisk dispatched Majors Donald MacLeod and Donald MacDonald, two officers in the 2nd battalion, 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants)

The 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was a British regiment in the American Revolutionary War that was raised to defend present day Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada from the constant land and sea attacks by American Revolutiona ...

who had recently served under the command of Major John Small during the June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in t ...

, to lead the recruitment drive in the Carolinas. Both recruiting officers were already aware of the clandestine activities of Allan MacDonald, the former Tacksman

A tacksman ( gd, Fear-Taic, meaning "supporting man"; most common Scots spelling: ''takisman'') was a landholder of intermediate legal and social status in Scottish Highland society.

Tenant and landlord

Although a tacksman generally paid a year ...

of Kingsburgh, Skye

Kingsburgh ( Gaelic: ''Cinnseaborgh'') is a scattered crofting township, overlooking Loch Snizort Beag on the Trotternish peninsula of the Isle of Skye in the Highlands of Scotland. It is in the council area of Highland. Kingsburgh is located ...

for Clan MacDonald of Sleat, and the husband of the Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald

Flora MacDonald ( Gaelic: ''Fionnghal nic Dhòmhnaill'', 1722 - 5 March 1790) was a member of Clan Macdonald of Sleat, best known for helping Charles Edward Stuart evade government troops after the Battle of Culloden in April 1746. Her family ...

. Allan MacDonald, who had emigrated to the Colony just a few years previously, was actively recruiting a Loyalist militia in North Carolina. The arrival of Majors MacLeod and MacDonald in the Colony's capital of New Bern

New Bern, formerly called Newbern, is a city in Craven County, North Carolina, United States. As of the 2010 census it had a population of 29,524, which had risen to an estimated 29,994 as of 2019. It is the county seat of Craven County and t ...

raised the suspicions of local officials from North Carolina's Committee of Safety, but MacLeod and MacDonald, "represented they were only visiting their friends and relatives." In reality, according to John Patterson MacLean, "They were all British officers, on active service

Active may refer to:

Music

* ''Active'' (album), a 1992 album by Casiopea

* Active Records, a record label

Ships

* ''Active'' (ship), several commercial ships by that name

* HMS ''Active'', the name of various ships of the British Royal ...

." Although the New Bern Committee dispatched a report to their superiors at Wilmington, both recruiting officers were allowed to proceed without being arrested.

According to historian John Patterson MacLean, Major Donald MacDonald was in his 65th year and had extensive combat experience as an officer in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

. Like MacLean of Torloisk, however, MacDonald had previously fought for Prince Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (20 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, grandson of James II and VII, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, Scotland and ...

during the Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took p ...

, during which the Major had, "headed many of his own name. He now found many of these former companions who readily listened to his persuasions."

On January 3, 1776, Governor Josiah Martin

Josiah Martin (23 April 1737 – 13 April 1786) was a British Army officer and colonial official who served as the ninth and last British governor of North Carolina from 1771 to 1776.

Early life and career

Martin was born in Dublin, Ireland, o ...

learned that more than 2,000 redcoats under the command of General Henry Clinton had been dispatched for the southern colonies from Cork, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

. Their arrival was expected in mid-February. Governor Martin immediately dispatched orders to all recruiting officers, decreeing that they were to be ready to lead their recruits to the coast by February 15th. Governor Martin also promoted Major Donald MacDonald to supreme commander of all British and Loyalist soldiers in the Colony of North Carolina, with the new rank of Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed to ...

.

Governor Martin also dispatched Alexander Maclean to Cross Creek with orders to coordinate activities in that area. Optimistically, Maclean promised Governor Martin to raise and equip 5,000 Regulators and 1,000 Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

. Governor Martin, expecting an easy Loyalist victory, is reported to have said, "This is the moment when this country may be delivered from anarchy."Wilson, p. 23

Proclamations were sent out demanding that, "all the King's loyal subjects... repair to the King's Royal Standard, at Cross Creek... in order to join the King's Army; otherwise, they must expect to fall under the melancholy consequences of a declared rebellion, and expose themselves to the just resentment of an injured, though gracious Sovereign." The latter statement would have been understood by North Carolina Highlanders as a threat that those who refused military service would be treated to both the land confiscations and the "arbitrary and malicious violence" used in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden (; gd, Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the Jacobite rising of 1745. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite army of Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force under Prince W ...

, which is still referred to in the Highlands and Islands as ''Bliadhna nan Creach'' (''"The Year of the Pillaging"'').

Beginning what would later be dubbed "The Insurrection of Clan Donald

Clan Donald, also known as Clan MacDonald ( gd, Clann Dòmhnaill; Mac Dòmhnaill ), is a Highland Scottish clan and one of the largest Scottish clans. The Lord Lyon King of Arms, the Scottish official with responsibility for regulating heraldry ...

", on February 1, 1776, Brigadier General MacDonald raised the Royal Standard

In heraldry and vexillology, a heraldic flag is a flag containing coats of arms, heraldic badges, or other devices used for personal identification.

Heraldic flags include banners, standards, pennons and their variants, gonfalons, guidons, and ...

in the Public Square of Cross Creek. Nightly balls were held and all other means were used to instill the military spirit. Behind the scenes, however, the Loyalist leadership was divided.

In a meeting of Scottish and Regulator leaders at Cross Creek on February 5, the Scots wanted to wait until the British troops arrived before mustering, while the Regulators wanted to move immediately. The views of the latter prevailed, particularly since they claimed to be able to raise 5,000 men, while the Gaels expected to raise only 700-800. When Loyalist forces gathered in Cross Creek on February 15, 1776, they numbered about 3,500 men.

According to J.P. MacLean, "When the day came, the Highlanders were seen coming from near and from far, from the wide plantations on the river bottoms, and from the rude cabins in the depths of the lonely pine forests, with broadswords at their side, in tartan garments and feather bonnet, and keeping step to the shrill music of the bag-pipe. There came, first of all, Clan MacDonald

Clan Donald, also known as Clan MacDonald ( gd, Clann Dòmhnaill; Mac Dòmhnaill ), is a Highland Scottish clan and one of the largest Scottish clans. The Lord Lyon King of Arms, the Scottish official with responsibility for regulating heraldry i ...

with Clan MacLeod

Clan MacLeod (; gd, Clann Mac Leòid ) is a Highland Scottish clan associated with the Isle of Skye. There are two main branches of the clan: the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan, whose chief is MacLeod of MacLeod, are known in Gaelic as ' ("se ...

near at hand, with lesser numbers of Clan MacKenzie

Clan Mackenzie ( gd, Clann Choinnich ) is a Scottish clan, traditionally associated with Kintail and lands in Ross-shire in the Scottish Highlands. Traditional genealogies trace the ancestors of the Mackenzie chiefs to the 12th century. However ...

, Clan Macrae

The Clan Macrae is a Highland Scottish clan. The clan has no chief; it is therefore considered an armigerous clan.

Surname

The surname Macrae (and its variations) is an anglicisation of the patronymic from the Gaelic personal name ''MacRaith' ...

, Clan MacLean, Clan MacKay

Clan Mackay ( ; gd, Clann Mhic Aoidh ) is an ancient and once-powerful Highland Scottish clan from the far North of the Scottish Highlands, but with roots in the old Kingdom of Moray. They supported Robert the Bruce during the Wars of Scottish ...

, Clan MacLachlan, and still others - variously estimated at fifteen hundred to three thousand, including about two hundred others, principally Regulators. However, all who were capable of bearing arms did not respond to the summons, for some would not engage in a cause where their traditions and affections had no part. Many of them hid in the swamps and in the forests."

According to tradition, as the Loyalist Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

gathered around the Royal Standard

In heraldry and vexillology, a heraldic flag is a flag containing coats of arms, heraldic badges, or other devices used for personal identification.

Heraldic flags include banners, standards, pennons and their variants, gonfalons, guidons, and ...

in the Public Square of Cross Creek, the formerly Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald

Flora MacDonald ( Gaelic: ''Fionnghal nic Dhòmhnaill'', 1722 - 5 March 1790) was a member of Clan Macdonald of Sleat, best known for helping Charles Edward Stuart evade government troops after the Battle of Culloden in April 1746. Her family ...

, "made to them an address in their own Gaelic tongue that excited them to the highest pitch of warlike enthusiasm", a tradition known among the Highland clans

A Scottish clan (from Gaelic , literally 'children', more broadly 'kindred') is a kinship group among the Scottish people. Clans give a sense of shared identity and descent to members, and in modern times have an official structure recognise ...

as a, "''brosnachadh-catha''" or an, "incitement to battle."

Despite Flora MacDonald's speech, however, the number of Loyalists dwindled rapidly over the next few days. Many of the Gaels had been promised that they would be met and escorted by British Army troops and did not favor having to fight all the way to the coast. When they marched from Cross Creek on February 18, 1776, Brigadier General Donald MacDonald led between 1,400 and 1,600 men, predominantly Scottish Gaels.Wilson, p. 35 This number was further reduced over the coming days as more and more men deserted the column.

Revolutionary reaction

Meanwhile, word of the Cross Creek muster reached the Patriots of the North Carolina Provincial Congress just a few days after it happened. The colonies were broadly prosperous on the eve of the American Revolution. Pursuant to resolutions of theSecond Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

, the provincial congress had raised the 1st North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

in fall 1775, and given command to Colonel James Moore. Local committees of safety in Wilmington and New Bern also had active militia units, led by Alexander Lillington and Richard Caswell

Richard Caswell (August 3, 1729November 10, 1789) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the first and fifth governor of the state of North Carolina from 1776 to 1780 and from 1785 to 1787. He also served as a senior officer of mi ...

respectively. On February 15, the Provincial Congress' militia force began to mobilize.Russell, p. 80

Moore led 650 Patriot militiamen out of Wilmington with the objective of preventing the loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped on the southern shore of Rockfish Creek on February 15, about from the loyalist camp. General MacDonald learned of their arrival, and sent Colonel Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on all Patriots to lay down their arms. Colonel Moore responded with his own call that the loyalists lay down ''their'' arms and support the cause of Congress. In the meantime, Caswell led 800

Moore led 650 Patriot militiamen out of Wilmington with the objective of preventing the loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped on the southern shore of Rockfish Creek on February 15, about from the loyalist camp. General MacDonald learned of their arrival, and sent Colonel Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on all Patriots to lay down their arms. Colonel Moore responded with his own call that the loyalists lay down ''their'' arms and support the cause of Congress. In the meantime, Caswell led 800 New Bern District Brigade

The New Bern District Brigade was an administrative division of the North Carolina militia during the American Revolutionary War (1776–1783). This unit was established by the North Carolina Provincial Congress on May 4, 1776, and disbanded at th ...

militiamen toward the area.Russell, p. 81 The Continentals included 58 English immigrants who had arrived in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and S ...

during the 1730s and 1740s and who were fighting for the patriot cause, as well as 290 of their sons who had been born and raised in the New World. In addition to this were eleven Welshman and 39 of their American born sons who also fought under Lillington. Smaller numbers of Lowland Scots immigrants, primarily from Selkirkshire

Selkirkshire or the County of Selkirk ( gd, Siorrachd Shalcraig) is a historic county and registration county of Scotland. It borders Peeblesshire to the west, Midlothian to the north, Roxburghshire to the east, and Dumfriesshire to the south. ...

, Berwickshire

Berwickshire ( gd, Siorrachd Bhearaig) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in south-eastern Scotland, on the English border. Berwickshire County Council existed from 1890 until 1975, when the area became part of t ...

and Roxburghshire

Roxburghshire or the County of Roxburgh ( gd, Siorrachd Rosbroig) is a historic county and registration county in the Southern Uplands of Scotland. It borders Dumfriesshire to the west, Selkirkshire and Midlothian to the north-west, and Berw ...

were also present on the patriot side. Many of the men who fought under Lillington and Caswell were third generation Carolinians whose grandparents had been English immigrants who came as part of a large migration to the Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nort ...

from the English regions of Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It is ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gover ...

as well as many farmers from the southern portion of Lincolnshire, England, during the early 1700s. By contrast, the Loyalist army facing them consisted exclusively of Gaelic-speaking Tories from the Scottish Highlands and Islands, some of whom owned large plantations along the Cape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a long blackwater river in east central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River (North Car ...

which was settled by recently arrived members of the Scottish nobility.

Loyalist march

MacDonald, his preferred road blocked by Moore, chose an alternate route that would eventually bring his force to the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge, about from Wilmington. On February 20 he crossed theCape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a long blackwater river in east central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River (North Car ...

at Cross Creek and destroyed the boats in order to deny Moore their use. His forces then crossed the South River, heading for Corbett's Ferry, a crossing of the Black River. On orders from Moore, Caswell reached the ferry first, and set up a blockade there.Wilson, p. 26 Moore, as a precaution against Caswell being defeated or circumvented, detached Lillington with 150 Wilmington militia and 100 men under Colonel John Ashe from the New Hanover Volunteer Company of Rangers to take up a position at the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge. These men, moving by forced marches, traveled down the southern bank of the Cape Fear River to Elizabethtown, where they crossed to the north bank. From there they marched down to the confluence of the Black River and Moore's Creek, and began entrenching on the east bank of the creek. Moore detached other militia companies to occupy Cross Creek, and followed Lillington and Ashe with the slower Continentals. They followed the same route, but did not arrive until after the battle.

When MacDonald and his force reached Corbett's Ferry, they found the crossing blocked by Caswell and his men. MacDonald prepared for battle, but was informed by a local slave that there was a second crossing a few miles up the Black River that they could use. On February 26, he ordered his rearguard to make a demonstration as if they were planning to cross while he led his main body up to this second crossing and headed for the bridge at Moore's Creek. Caswell, once he realized that MacDonald had given him the slip, hurried his men the to Moore's Creek, and beat MacDonald there by only a few hours. MacDonald sent one of his men into the patriot camp under a flag of truce to demand their surrender, and to examine the defences. Caswell refused, and the envoy returned with a detailed plan of the patriot fortifications.Russell, p. 82

Caswell had thrown up some entrenchments on the west side of the bridge, but these were not located to patriot advantage. Their position required the patriots to defend a position whose only line of retreat was across the narrow bridge, a distinct disadvantage that MacDonald recognized when he saw the plans.Wilson, p. 27 In a council held that night, the loyalists decided to attack, since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area. During the night, Caswell decided to abandon that position and instead take up a position on the far side of the creek. To further complicate the loyalists' use of the bridge, the militia took up its planking and greased the support rails.Wilson, p. 28

Caswell had thrown up some entrenchments on the west side of the bridge, but these were not located to patriot advantage. Their position required the patriots to defend a position whose only line of retreat was across the narrow bridge, a distinct disadvantage that MacDonald recognized when he saw the plans.Wilson, p. 27 In a council held that night, the loyalists decided to attack, since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area. During the night, Caswell decided to abandon that position and instead take up a position on the far side of the creek. To further complicate the loyalists' use of the bridge, the militia took up its planking and greased the support rails.Wilson, p. 28

Battle

By the time of their arrival at Moore's Creek, the loyalist contingent had shrunk to between 700 and 800 men. About 600 of these were Highland Scots and the remainder were Regulators. Furthermore, the marching had taken its toll on the elderly Brigadier General MacDonald; he fell ill and turned over command to Lieutenant Colonel Donald MacLeod. The loyalists broke camp at 1 am on February 27 and marched the few miles from their camp to the bridge. During the night, Caswell and his men established a semicircular earthworks around the bridge end, and prepared to defend them with two small pieces offield artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support army, armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the ear ...

.

Arriving shortly before dawn, the Loyalists found the defenses on the west side of the bridge unoccupied. MacLeod ordered his men to adopt a defensive line behind nearby trees, but then a Patriot sentry across the river fired his musket to warn Caswell of the loyalist arrival. Hearing this, Lt.-Col. MacLeod immediately ordered his men to attack.

In the pre-dawn mist, a company of Loyalist Gaels approached the bridge. In response to a Patriot call for identification shouted from across the creek, Captain Alexander Mclean identified himself as a friend of the King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ti ...

, and responded with his own challenge in Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

. Hearing no reply, he ordered his company to open fire, beginning an exchange of gunfire with the Patriot sentries. Lieutenant-Colonel MacLeod and Captain John Campbell then led a hand-picked company of swordsmen on a Highland charge across the bridge, shouting in Gaelic, "King George and broadsword

The basket-hilted sword is a sword type of the early modern era characterised by a basket-shaped guard that protects the hand. The basket hilt is a development of the quillons added to swords' crossguards since the Late Middle Ages.

In mod ...

s!"

When the Loyalists were within 30 paces of the earthworks, the Patriot militia opened fire to devastating effect. MacLeod and Campbell both went down in a hail of gunfire; Colonel Moore reported that MacLeod had been struck by more than 20 musket balls. Armed only with swords and faced with the overwhelming firepower of Patriot muskets and artillery, the Highland Scots could do little else other than retreat. The surviving elements of Campbell's company got back over the bridge, and the governor's force dissolved and retreated.Wilson, p. 29

Capitalising on the success, the Revolutionary forces quickly replaced the bridge planking and gave chase. One enterprising company led by one of Caswell's lieutenants forded the creek above the bridge, flanking the retreating loyalists. Colonel Moore arrived on the scene a few hours after the battle. He stated in his report that 30 loyalists were killed or wounded, "but as numbers of them must have fallen into the creek, besides more that were carried off, I suppose their loss may be estimated at fifty."Wilson, p. 30 The Revolutionary leaders reported one killed and one wounded.

Aftermath

Over the next several days, the North Carolina Provincial Congress' militia force mopped up the fleeing loyalists. In all, about 850 men were captured. Most of these were released on parole, but the ringleaders were sent toPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

as prisoners. Despite very hard feelings on both sides, the Loyalist prisoners were treated with respect. This helped convince many not to take up arms again. Wilson, p. 33

Among those who survived to be taken prisoner was the Loyalist war poet

A war poet is a poet who participates in a war and writes about their experiences, or a non-combatant who writes poems about war. While the term is applied especially to those who served during the First World War, the term can be applied to a p ...

Iain mac Mhurchaidh

Iain mac Mhurchaidh, alias John MacRae (died ca. 1780), was a Scotland-born Bard from Kintail, a member of Clan Macrae, and an early immigrant to the Colony of North Carolina. MacRae has been termed one of the "earliest Scottish Gaelic poets in ...

(John Macrae), a member of Clan Macrae

The Clan Macrae is a Highland Scottish clan. The clan has no chief; it is therefore considered an armigerous clan.

Surname

The surname Macrae (and its variations) is an anglicisation of the patronymic from the Gaelic personal name ''MacRaith' ...

, recent immigrant from Kintail

Kintail ( gd, Cinn Tàile) is an area of mountains in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland, located in the Highland Council area. It consists of the mountains to the north of Glen Shiel and the A87 road between the heads of Loch Duich and Loch ...

, and important figure in Scottish Gaelic literature

Scottish Gaelic literature refers to literature composed in the Scottish Gaelic language and in the Gàidhealtachd communities where it is and has been spoken. Scottish Gaelic is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages, along with Iris ...

. The poet's son, Murdo Macrae, also fought on the Loyalist side during the battle and was mortally wounded.

Combined with the capture of the loyalist camp at Cross Creek, the patriots confiscated 1,500 muskets, 300 rifles, and $15,000 (as valued at the time) of Spanish gold.Russell, p. 83 Many of the weapons were probably hunting equipment, and may have been taken from people not directly involved in the loyalist uprising.Wilson, p. 31 The action had a galvanizing effect on patriot recruiting, and the arrests of many loyalist leaders throughout North Carolina cemented patriot control of the state. A pro-patriot newspaper reported after the battle, "This, we think, will effectually put a stop to loyalists in North Carolina".Wilson, p. 33

The battle had significant effects among the Scottish Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

of North Carolina, where loyalist sympathisers refused to take up arms whenever recruitment efforts were made later in the war, and those who did were routed out of their homes by the pillaging activities of their patriot neighbors.

When news of the battle reached London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

, it received mixed commentary. One news report minimised the defeat since it did not involve any regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standi ...

troops, while another noted that an "inferior" patriot force had defeated the loyalists. Lord George Germain, the British official responsible for managing the war in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

, remained convinced in spite of the resounding defeat that loyalists were still a substantial force to be tapped.

The expedition that the loyalists had been planning to meet was significantly delayed, and did not depart Cork, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

until mid-February. The convoy was further delayed and split apart by bad weather, so the full force did not arrive off Cape Fear until May 1776.Russell, p. 85 As the fleet gathered, North Carolina's provincial congress met at Halifax, North Carolina, and in early April passed the Halifax Resolves

The Halifax Resolves was a name later given to the resolution adopted by the North Carolina Provincial Congress on April 12, 1776. The adoption of the resolution was the first official action in the American Colonies calling for independence from ...

, authorizing the colony's delegates to the Continental Congress to vote in favor of declaring independence from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

.Russell, p. 84 General Clinton used the force in an attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint ...

. His attempt, at the Battle of Sullivan's Island

The Battle of Sullivan's Island or the Battle of Fort Sullivan was fought on June 28, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. It took place near Charleston, South Carolina, during the first British attempt to capture the city from America ...

, failed and it represented the last significant British attempts to retake control of the southern colonies until late 1778.Wilson, p. 56

A Pro-Patriot newspaper in Virginia angrily condemned Bridadier-General MacDonald by pointing out that King George III, whom he now served, came from the very dynasty that MacDonald had once considered usurpers and tried to depose during the Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took p ...

. Yet, as the newspaper pointed out, Brigadier General MacDonald now viewed American Patriots as rebels and traitors against their, "lawful King." Ironically, the Crown ultimately showed the Brigadier-General little or no appreciation.

While he was held as a POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, efforts to negotiate a prisoner exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners: prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc. Sometimes, dead bodies are involved in an exchange.

Geneva Conventions

Under the Geneva Conve ...

for Brigadier General Donald MacDonald, were always hampered afterwards; as the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

refused to accept MacDonald's promotion by Governor Josiah Martin

Josiah Martin (23 April 1737 – 13 April 1786) was a British Army officer and colonial official who served as the ninth and last British governor of North Carolina from 1771 to 1776.

Early life and career

Martin was born in Dublin, Ireland, o ...

from Major to Brigadier General, and the Continental Congress refused to authorize George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

to exchange MacDonald for a captured Patriot officer of lower than Brigadier General's rank.

Meanwhile, General MacDonald's son, a fellow Jacobite veteran of the 1745 uprising who was also named Donald MacDonald, joined the Patriot side very soon after his father was taken prisoner following the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge. According to historian J.P. MacLean, "The son was a remarkably stout, red-haired young Scotsman, cool under the most trying difficulties and brave without a fault."

MacDonald attained the rank of Sergeant and, "was the subject of many tales of daring exploits".

When asked by his commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitud ...

, General Peter Horry, however, why he had abandoned his father's party and joined "the rebels", Sgt. MacDonald replied,

As related in General Horry's memoirs, Sgt. MacDonald once posed as a British Legion soldier and asked a Loyalist plantation owner to give up his best stallion

A stallion is a male horse that has not been gelded ( castrated).

Stallions follow the conformation and phenotype of their breed, but within that standard, the presence of hormones such as testosterone may give stallions a thicker, "cresty" n ...

for Lieut.-Col. Banastre Tarleton

Sir Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet, GCB (21 August 175415 January 1833) was a British general and politician. He is best known as the lieutenant colonel leading the British Legion at the end of the American Revolution. He later served in Portug ...

's personal use. Overjoyed, the planter handed Sgt. MacDonald a pedigreed stallion named Selim, which the Sergeant always rode in later years. Furthermore, when the planter visited Tarleton's camp to ask the Lietenant-Colonel how he liked his new mount, the response of both men to the realization that they had been had is best described as unprintable.

Sergeant MacDonald was serving under General Francis Marion

Brigadier-General Francis Marion ( 1732 – February 27, 1795), also known as the Swamp Fox, was an American military officer, planter and politician who served during the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War. During the Ameri ...

when he was killed in action during the Siege of Fort Motte on May 12, 1781. According to historian J.P. MacLean, "His resting place is unknown. No monument has been erected to his memory; but his name will endure so long as men shall pay respect to heroism and devotion to country."

After the battle, Flora MacDonald

Flora MacDonald ( Gaelic: ''Fionnghal nic Dhòmhnaill'', 1722 - 5 March 1790) was a member of Clan Macdonald of Sleat, best known for helping Charles Edward Stuart evade government troops after the Battle of Culloden in April 1746. Her family ...

was interrogated by the North Carolina Committee of Safety, before which she exhibited "spirited behavior." Soon afterwards, however, Flora experienced the deaths of all her children during a typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

epidemic. At her imprisoned husband's urging, Flora MacDonald set out to return in 1779 from North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and S ...

to her native village of Milton, South Uist

South Uist ( gd, Uibhist a Deas, ; sco, Sooth Uist) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the ...

. With the assistance of a sympathetic Patriot officer named Captain Ingrahm, MacDonald was granted a passport allowing her to cross the lines and take passage aboard a ship from British-held Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint ...

for Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

. MacDonald continued facing severe trials, which included having her left arm broken during an attack by a French privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

upon the ship aboard which she was later returning to Scotland. In the end, Flora arrived safely and her brother built her a cottage to live in at Milton.

In 1781, when General Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

passed through the Cross Creek area, he reported that " ny of the inhabitants rode into camp, shook me by the hand, said they were glad to see us and that we had beat Greene and then rode home."

Following the end of the war, many regions of North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and S ...

which had been mainly settled by Scottish Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

, were almost depopulated, as Gaelic-speaking Loyalists fled northward towards what remained of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

.

Similarly to Brigadier General MacDonald, however, Allan and Flora MacDonald found the race of the Georges very unappreciative for their sufferings. As the Crown refused to fully reimburse them for the confiscation of 'Killegray', their slave plantation in Anson County, North Carolina

Anson County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 22,055. Its county seat is Wadesboro.

History

The county was formed in 1750 from Bladen County. It was named for George Anson, ...

, Allan and Flora MacDonald lacked the financial means to resettle in Canada and were forced to return to Scotland. Flora always said in her later life that she first served the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter ...

and then the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house ori ...

and that she was worsted in the cause of each. Flora MacDonald died on March 5, 1790.

According to Marcus Tanner, despite the post-Revolutionary War flight of many local United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America ...

and the subsequent redirection of Scottish Highland emigration to Canada, a large Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The term ...

community continued to exist in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and S ...

, "until it was well and truly disrupted", by the American Civil War.

Even so, local pride in the Scottish heritage of local pioneers remains very a part of the Culture of North Carolina. One of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the C ...

's largest Highland Games, the Grandfather Mountain

Grandfather Mountain is a mountain, a non-profit attraction, and a North Carolina state park

near Linville, North Carolina. At 5,946 feet (1,812 m), it is the highest peak on the eastern escarpment of the Blue Ridge Mountains, one of the major ...

Highland Games, are held there every year and draw in visitors from all over the world. The Grandfather Mountain games have been called "the best" such event in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

because of the spectacular landscape and the large number of people who attend in kilt

A kilt ( gd, fèileadh ; Irish: ''féileadh'') is a garment resembling a wrap-around knee-length skirt, made of twill woven worsted wool with heavy pleats at the sides and back and traditionally a tartan pattern. Originating in the Scottish H ...

s and other regalia of the Scottish clan

A Scottish clan (from Gaelic , literally 'children', more broadly 'kindred') is a kinship group among the Scottish people. Clans give a sense of shared identity and descent to members, and in modern times have an official structure recognise ...

s. It is also widely considered to be the largest "gathering of clans" in North America, as more family lines are represented there than any other similar event.

The Moore's Creek Bridge battlefield site was preserved in the late 19th century through private efforts that eventually received state financial support. The Federal government took over the battle site as a National Military Park operated by the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

{{ ...

in 1926. The War Department operated the park until 1933, when the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

took over the site as the Moores Creek National Battlefield

Moores Creek National Battlefield is a battlefield managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The park commemorates the 1776 victory of a thousand patriots over about eight hundred loyalists at Moore's Creek. The battle dashed the hopes of ...

. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

in 1966. The battle is commemorated every year during the last full weekend of February.

Order of battle

Early accounts of the battle often misstated the size of both forces involved in the battle, typically reporting that 1,600 loyalists faced 1,000 patriots. These numbers are still used by the National Park Service.North Carolina

The patriot forces were also underreported since Caswell apparently casually grouped the ranger forces of John Ashe as part of Lillington's company in his report. The Provincial Congress' militia forces order of battle included a mix of North Carolina Minutemen and Militia units. Because of the performance of the local militia and the higher costs of Minutemen, the North Carolina General Assembly abandoned the use of Minutemen on April 10, 1776 in favor of local militia brigades and regiments. The following units participated in this battle:Lewis Minutemen and State Troops: * New Bern District Minutemen Battalion, 13 companies * Wilmington District Minutemen Battalion, 4 companies * Halifax District Minutemen Battalion, 5 companies * Hillsborough District Minutemen Battalion, 7 companies * 1st Salisbury District Minutemen Battalion, 1 company * 2nd Salisbury District Minutement Battalion, 11 companies * 1st North Carolina Regiment, 7 companies Local Militia: * Halifax District Brigade ** Halifax County Regiment, 1 company ** Northampton County Regiment, 1 company *Hillsborough District Brigade

The Hillsborough District Brigade of militia was an administrative division of the North Carolina militia established on May 4, 1776. Brigadier General Thomas Person was the first commander. Companies from the eight regiments of the brigade wer ...

** Chatham County Regiment, 4 companies

** Granville County Regiment, 1 company

** Orange County Regiment, 1 company

** Wake County Regiment, 4 companies

* New Bern District Brigade

The New Bern District Brigade was an administrative division of the North Carolina militia during the American Revolutionary War (1776–1783). This unit was established by the North Carolina Provincial Congress on May 4, 1776, and disbanded at th ...

** Craven County Regiment, 4 companies

** Dobbs County Regiment

The Dobbs County Regiment was a unit of the North Carolina militia that served during the American Revolution. The regiment was one of thirty-five existing county militias that were authorized by the North Carolina Provincial Congress to be organ ...

, 8 companies

** Johnston County Regiment, 5 companies

** Pitt County Regiment, 4 companies

* Salisbury District Brigade

The Salisbury District Brigade was an administrative division of the North Carolina militia during the American Revolutionary War (1776–1783). This unit was established by the Fourth North Carolina Provincial Congress on May 4, 1776, and disba ...

** Anson County Regiment, 2 companies

** Guilford County Regiment, 12 companies

** Surry County Regiment, 3 companies

** Tryon County Regiment, 8 companies

* Wilmington District Brigade

** Bladen County Regiment, 8 companies

** Brunswick County Regiment, 1 company

** Cumberland County Regiment, 2 companies

** Duplin County Regiment, 10 companies

** Onslow County Regiment, 3 companies

** New Hannover County Regiment, 2 companies of volunteer independent rangers

Great Britain

Historian David Wilson, however, points out that the large loyalist size is attributed to reports by General MacDonald and Colonel Caswell. MacDonald gave that figure to Caswell, and it represents a reasonable estimate of the number of men starting the march at Cross Creek. Alexander Mclean, who was present at both Cross Creek and the battle, reported that only 800 loyalists were present at the battle, as did Governor Martin.References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

"The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge," ''Revolutionary North Carolina''

a digital textbook produced by the UNC School of Education. {{DEFAULTSORT:Moore's Creek Bridge, Battle of 1776 in North Carolina Moore's Creek Bridge Battles involving Great Britain Battles involving the United States Moore's Creek Bridge Moore's Creek Bridge February 1776 events Last stands Pender County, North Carolina Scottish-American culture in North Carolina Scottish-American history