Battle Of Madagascar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Madagascar (5 May – 6 November 1942) was a British campaign to capture the

Force 121 left the Clyde in Scotland on 23 March and joined with South African-born Syfret's ships at

Force 121 left the Clyde in Scotland on 23 March and joined with South African-born Syfret's ships at

The beach landings met with virtually no resistance and these troops seized Vichy coastal batteries and barracks. The Courier Bay force, the 17th Infantry Brigade, after toiling through

The beach landings met with virtually no resistance and these troops seized Vichy coastal batteries and barracks. The Courier Bay force, the 17th Infantry Brigade, after toiling through

Hostilities continued at a low level for several months. After 19 May two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division were transferred to India. On 8 June, the 22nd (East Africa) Brigade Group arrived on Madagascar. The 7th South African Motorized Brigade arrived on 24 June. On 2 July, an invasion force was sent to the Vichy-held island of

Hostilities continued at a low level for several months. After 19 May two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division were transferred to India. On 8 June, the 22nd (East Africa) Brigade Group arrived on Madagascar. The 7th South African Motorized Brigade arrived on 24 June. On 2 July, an invasion force was sent to the Vichy-held island of

With Madagascar in their hands, the Allies established military and naval installations across the island. The island was crucial for the rest of the war. Its deep water ports were vital for control of the passageway to India and the Persian corridor, and were now beyond the grasp of the Axis. This was the first large-scale operation of World War II by the Allies combining sea, land, and air forces. In the makeshift Allied planning of the war's early years, the invasion of Madagascar held a prominent strategic place.

Historian John Grehan has claimed that the British capture of Madagascar before it could fall into Japanese hands was so crucial in the context of the war that it led to Japan's eventual downfall and defeat.

Free French General

With Madagascar in their hands, the Allies established military and naval installations across the island. The island was crucial for the rest of the war. Its deep water ports were vital for control of the passageway to India and the Persian corridor, and were now beyond the grasp of the Axis. This was the first large-scale operation of World War II by the Allies combining sea, land, and air forces. In the makeshift Allied planning of the war's early years, the invasion of Madagascar held a prominent strategic place.

Historian John Grehan has claimed that the British capture of Madagascar before it could fall into Japanese hands was so crucial in the context of the war that it led to Japan's eventual downfall and defeat.

Free French General

;Battleships

:

;Aircraft Carriers

:

:

;Cruisers

:

:

:

:

:

:

;Minelayer

:

;Monitor

:

;Seaplane Carrier

:

;Destroyers

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

;Corvettes

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

;Minesweepers

:

: HMS ''Poole''

: HMS ''Romney''

: HMS ''Cromarty''

;Assault transports

:HMS ''Winchester Castle''

:HMS ''Royal Ulsterman''

:HMS ''Keren''

:HMS ''Karanja''

: (Polish)

;Special ships

:HMS ''Derwentdale'' (LCA)

:HMS ''Bachaquero'' (LST)

;Troop ships

:

:

:

;Stores and MT ships

: SS ''Empire Kingsley''

:M/S ''Thalatta''

:SS ''Mahout''

:SS ''City of Hong Kong''

:SS ''Mairnbank''

:SS ''Martand II''

;Naval Ground Forces

:

;Battleships

:

;Aircraft Carriers

:

:

;Cruisers

:

:

:

:

:

:

;Minelayer

:

;Monitor

:

;Seaplane Carrier

:

;Destroyers

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

;Corvettes

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

;Minesweepers

:

: HMS ''Poole''

: HMS ''Romney''

: HMS ''Cromarty''

;Assault transports

:HMS ''Winchester Castle''

:HMS ''Royal Ulsterman''

:HMS ''Keren''

:HMS ''Karanja''

: (Polish)

;Special ships

:HMS ''Derwentdale'' (LCA)

:HMS ''Bachaquero'' (LST)

;Troop ships

:

:

:

;Stores and MT ships

: SS ''Empire Kingsley''

:M/S ''Thalatta''

:SS ''Mahout''

:SS ''City of Hong Kong''

:SS ''Mairnbank''

:SS ''Martand II''

;Naval Ground Forces

:

;29th Infantry Brigade (independent) arrived via amphibious landing near Diego-Suarez on 5 May 1942

:2nd South Lancashire Regiment

:2nd East Lancashire Regiment

:1st

;29th Infantry Brigade (independent) arrived via amphibious landing near Diego-Suarez on 5 May 1942

:2nd South Lancashire Regiment

:2nd East Lancashire Regiment

:1st

:Merchant Cruiser

:Sloop

;Submarines

:

:

:

:Merchant Cruiser

:Sloop

;Submarines

:

:

:

;West coast

:Two platoons of reservists and volunteers at Nossi-Bé

:Two companies of the ''Régiment mixte malgache'' (RMM – Mixed Madagascar Regiment) at

;West coast

:Two platoons of reservists and volunteers at Nossi-Bé

:Two companies of the ''Régiment mixte malgache'' (RMM – Mixed Madagascar Regiment) at

exordio.com, ?, "Operación Ironclad" (Spanish language)

''BBC History'' magazine podcast about the Battle of Madagascar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Madagascar 1942, Battle Of Battles of World War II involving Japan Land battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Battles and operations of World War II involving South Africa Conflicts in 1942 History of Madagascar Military battles of Vichy France World War II occupied territories 1942 in France 1942 in Madagascar Amphibious operations of World War II Amphibious operations involving the United Kingdom

Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

-controlled island Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The seizure of the island by the British was to deny Madagascar's ports to the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

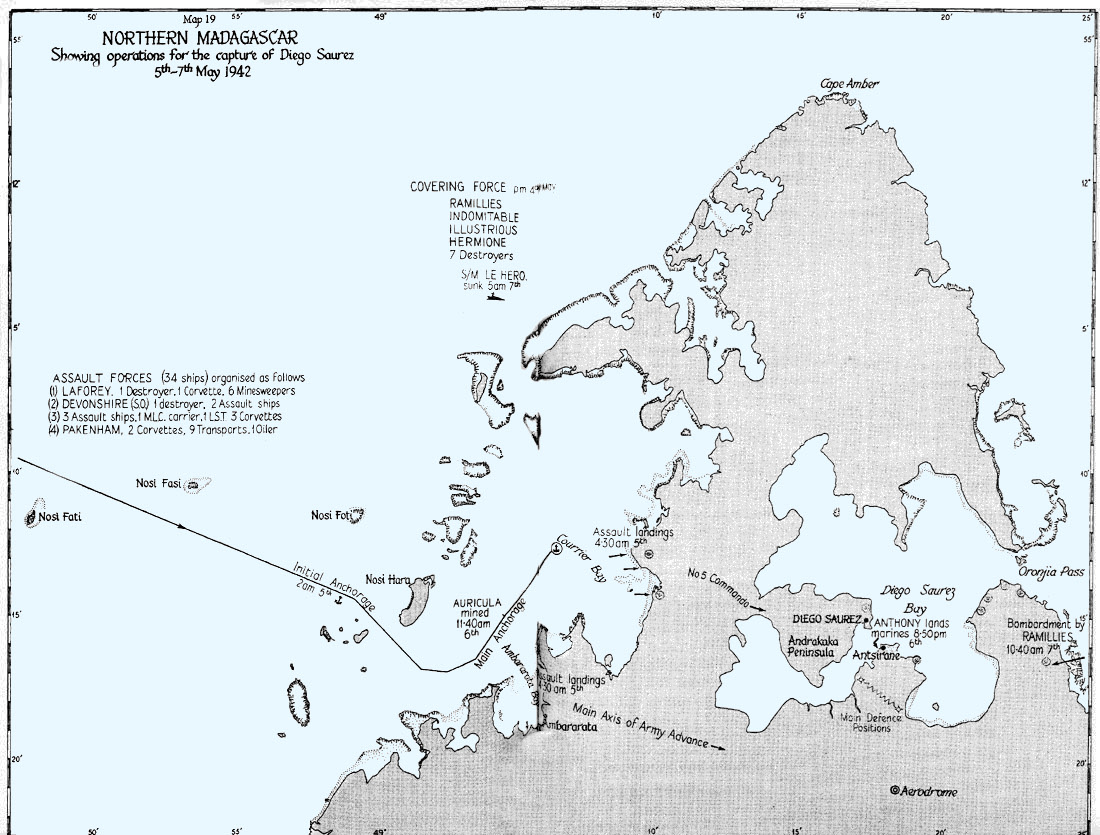

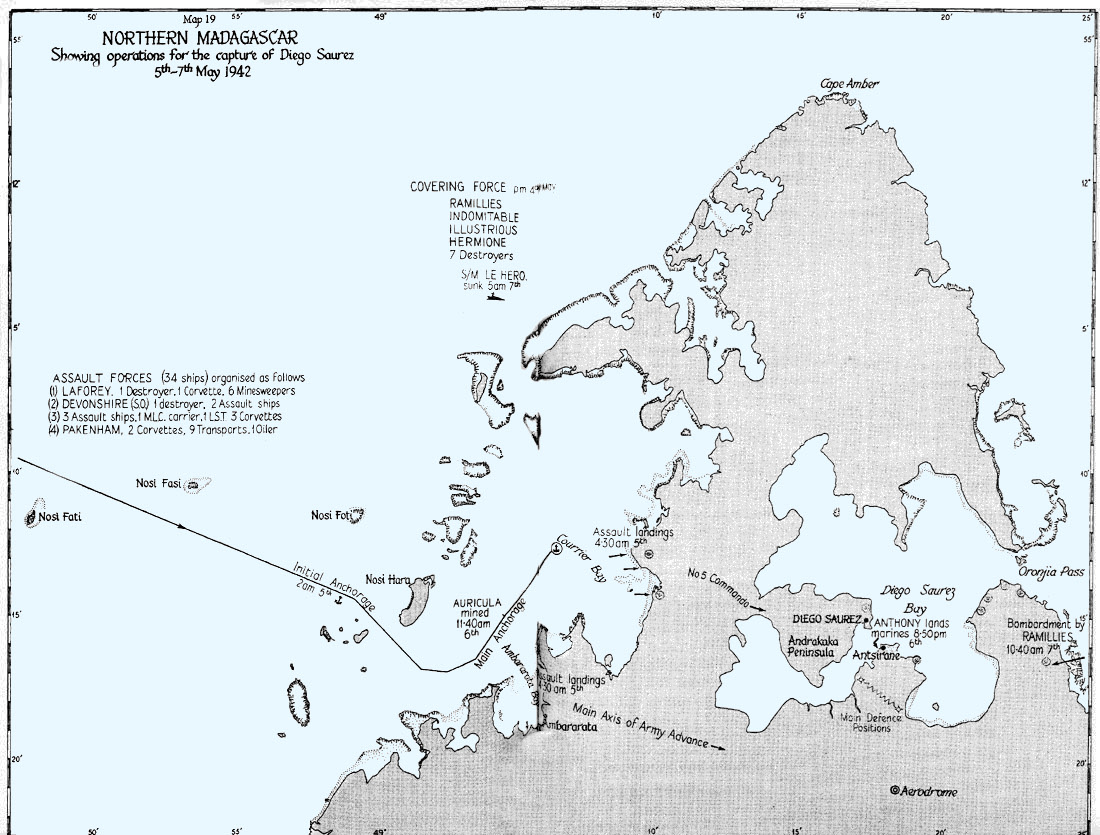

and to prevent the loss or impairment of the Allied shipping routes to India, Australia and Southeast Asia. It began with Operation Ironclad, the seizure of the port of Diego-Suarez (now Antsiranana

Antsiranana ( mg, Antsiran̈ana ), named Diego-Suárez prior to 1975, is a city in the far north of Madagascar. Antsiranana is the capital of Diana Region. It had an estimated population of 115,015 in 2013.

History

The bay and city originally ...

) near the northern tip of the island, on 5 May 1942.

A subsequent campaign to secure the entire island, Operation Stream Line Jane, was opened on 10 September. The Allies broke into the interior, linking up with forces on the coast and secured the island by the end of October. Fighting ceased and an armistice was granted on 6 November. This was the first large-scale operation by the Allies combining sea, land and air forces. The island was placed under Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

control.Rigge p. 100

Background

Geopolitical

Diego-Suarez

Antsiranana ( mg, Antsiran̈ana ), named Diego-Suárez prior to 1975, is a city in the far north of Madagascar. Antsiranana is the capital of Diana Region. It had an estimated population of 115,015 in 2013.

History

The bay and city originally u ...

is a large bay, with a fine harbour, near the northern tip of the island of Madagascar. It has an opening to the east through a narrow channel called Oronjia Pass. The naval base of Diego-Suarez lies on a peninsula between two of the four small bays enclosed within Diego-Suarez Bay. The bay cuts deeply into the northern tip of Madagascar's Cape Amber, almost severing it from the rest of the island. In the 1880s, the bay was coveted by France, which claimed it as a coaling station

Fuelling stations, also known as coaling stations, are repositories of fuel (initially coal and later oil) that have been located to service commercial and naval vessels. Today, the term "coaling station" can also refer to coal storage and feedi ...

for steamships travelling to French possessions farther east. The colonization was formalized after the first Franco-Hova War

The Franco-Hova Wars, also known as the Franco-Malagasy Wars were two French military interventions in Madagascar between 1883 and 1896 that overthrew the ruling monarchy of the Merina Kingdom, and resulted in Madagascar becoming a French colo ...

when Queen Ranavalona III

Ranavalona III (; 22 November 1861 – 23 May 1917) was the last sovereign of the Kingdom of Madagascar. She ruled from 30 July 1883 to 28 February 1897 in a reign marked by ultimately futile efforts to resist the colonial designs of the go ...

signed a treaty on 17 December 1885 giving France a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

over the bay and surrounding territory; as well as the islands of Nosy Be and St. Marie de Madagascar. The colony's administration was subsumed into that of French Madagascar

The Colony of Madagascar and Dependencies (french: Colonie de Madagascar et dépendances) was a French colony off the coast of Southeast Africa between 1897 and 1958 in what is now Madagascar. The colony was formerly a protectorate of France ...

in 1897.

In 1941, Diego-Suarez town, the bay and the channel were well protected by naval shore batteries.

Vichy

Following the Japaneseconquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, ...

of Southeast Asia east of Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

by the end of February 1942, submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy

Imperial Japanese Navy submarines originated with the purchase of five Holland type submarines from the United States in 1904. Japanese submarine forces progressively built up strength and expertise, becoming by the beginning of World War II one o ...

moved freely throughout the north and eastern expanses of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

. In March, Japanese aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s raided merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

s in the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line bet ...

, and attacked bases in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

and Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

in Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(now Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

). This raid drove the British Eastern Fleet out of the area and they were forced to relocate to a new base at Kilindini Harbour

Kilindini Harbour is a large, natural deep-water inlet extending inland from Mombasa, Kenya. It is at its deepest center, although the controlling depth is the outer channel in the port approaches with a dredged depth of . It serves as the harbo ...

, Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town ...

, Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

.

The move made the British fleet more vulnerable to attack. The possibility of Japanese naval forces using forward bases in Madagascar had to be addressed. The potential use of these facilities particularly threatened Allied merchant shipping, the supply route to the British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was an Allied field army formation of the British Army during the Second World War, fighting in the North African and Italian campaigns. Units came from Australia, British India, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Free French Force ...

and also the Eastern Fleet.

Japanese Kaidai-type submarines had the longest range of any Axis submarines at the time – more than in some cases, but being challenged by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

's then-relatively new fleet submarine

A fleet submarine is a submarine with the speed, range, and endurance to operate as part of a navy's battle fleet. Examples of fleet submarines are the British First World War era K class and the American World War II era ''Gato'' class.

The t ...

s' top range figures. If the Imperial Japanese Navy's submarines could use bases on Madagascar, Allied lines of communication would be affected across a region stretching from the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and as far as the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe a ...

.

On 17 December 1941, Vice Admiral Fricke, Chief of Staff of Germany's Maritime Warfare Command (''Seekriegsleitung''), met Vice Admiral Naokuni Nomura, the Japanese naval attaché

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

, in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

to discuss the delimitation of respective operational areas between the German ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'' and Imperial Japanese Navy forces. At another meeting on 27 March 1942, Fricke stressed the importance of the Indian Ocean to the Axis powers and expressed the desire that the Japanese begin operations against the northern Indian Ocean sea routes. Fricke further emphasized that Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

, and Madagascar should have a higher priority for the Axis navies than operations against Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. By 8 April, the Japanese announced to Fricke that they intended to commit four or five submarines and two auxiliary cruisers for operations in the western Indian Ocean between Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 peopl ...

and the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

, but they refused to disclose their plans for operations against Madagascar and Ceylon, only reiterating their commitment to operations in the area.

Allies

The Allies had heard the rumours of Japanese plans for the Indian Ocean and on 27 November 1941, the British Chiefs of Staff discussed the possibility that theVichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

might cede the whole of Madagascar to Japan, or alternatively permit the Japanese Navy to establish bases on the island. British naval advisors urged the occupation of the island as a precautionary measure. On 16 December, General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

, leader of the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

in London, sent a letter to the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, in which he also urged a Free French operation against Madagascar. Churchill recognised the risk of a Japanese-controlled Madagascar to Indian Ocean shipping, particularly to the important sea route to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, and considered the port of Diego-Suarez

Antsiranana ( mg, Antsiran̈ana ), named Diego-Suárez prior to 1975, is a city in the far north of Madagascar. Antsiranana is the capital of Diana Region. It had an estimated population of 115,015 in 2013.

History

The bay and city originally u ...

as the strategic key to Japanese influence in the Indian Ocean. However, he also made it clear to planners that he did not feel Britain had the resources to mount such an operation and, following experience in the Battle of Dakar

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the success of the operation cou ...

in September 1940, did not want a joint operation launched by British and Free French forces to secure the island.

By 12 March 1942, Churchill had been convinced of the importance of such an operation and the decision was reached that the planning of the invasion of Madagascar would begin in earnest. It was agreed that the Free French would be explicitly excluded from the operation. As a preliminary battle outline, Churchill gave the following guidelines to the planners and the operation was designated Operation Bonus:

* Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

, the ships guarding the Western Mediterranean, should move south from Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

and should be replaced by an American Task Force

* The 4,000 men and ships proposed by Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

for the operation, should be retained as the nucleus around which the plan should be built

* The operation should commence around 30 April 1942

* In the event of success, the commandos

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

recommended by Mountbatten should be replaced by garrison troops as soon as possible

On 14 March, Force 121 was constituted under the command of Major-General Robert Sturges of the Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious warfare, amphibious light infantry and also one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighti ...

with Rear-Admiral Edward Syfret being placed in command of naval Force H and the supporting sea force.

Allied preparations

Force 121 left the Clyde in Scotland on 23 March and joined with South African-born Syfret's ships at

Force 121 left the Clyde in Scotland on 23 March and joined with South African-born Syfret's ships at Freetown

Freetown is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educ ...

in Sierra Leone, proceeding from there in two convoys to their assembly point at Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

on the South African east coast. Here they were joined by the 13th Brigade Group of the 5th Division – General Sturges' force consisting of three infantry brigades, while Syfret's squadron consisted of the flag battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

, the aircraft carriers and , the cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several ...

s and , eleven destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s, six minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s, six corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

s and auxiliaries. It was a formidable force to bring against the 8,000 troops (mostly conscripted Malagasy) at Diego-Suarez, but the chiefs of staff were adamant that the operation was to succeed, preferably without any fighting.

This was to be the first British amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted u ...

since the disastrous landings in the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

twenty-seven years before.

During the assembly in Durban, Field-Marshal Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

pointed out that the mere seizure of Diego-Suarez would be no guarantee against continuing Japanese aggression and urged that the ports of Majunga

Mahajanga (French: Majunga) is a city and an administrative district on the northwest coast of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: Rép ...

and Tamatave

Toamasina (), meaning "like salt" or "salty", unofficially and in French Tamatave, is the capital of the Atsinanana region on the east coast of Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. The city is the chief seaport of the country, situated northeast of it ...

be occupied as well. This was evaluated by the chiefs of staff, but it was decided to retain Diego-Suarez as the only objective due to the lack of manpower. Churchill remarked that the only way to permanently secure Madagascar was by means of a strong fleet and adequate air support operating from Ceylon and sent General Archibald Wavell

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior officer of the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the First World War, during which he was wounded i ...

(India Command) a note stating that as soon as the initial objectives had been met, all responsibility for safeguarding Madagascar would be passed on to Wavell. He added that when the commandos were withdrawn, garrison duties would be performed by two African brigades and one brigade from the Belgian Congo or west coast of Africa.

In March and April, the South African Air Force

"Through hardships to the stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment ...

(SAAF) had conducted reconnaissance flights over Diego-Suarez and No. 32, 36 and 37 Coastal Flights were withdrawn from maritime patrol operations and sent to Lindi on the Indian Ocean coast of Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

, with an additional eleven Bristol Beauforts and six Martin Maryland

The Martin Model 167 Maryland was an American medium bomber that first flew in 1939. It saw action in World War II with France and the United Kingdom.

Design and development

In response to a December 1937 United States Army Air Corps requiremen ...

s to provide close air support during the planned operations.

Campaign

Allied commanders decided to launch anamphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted u ...

on Madagascar. The task was Operation Ironclad, executed by Force 121. It included Allied naval, land and air forces and was commanded by Major-General Robert Sturges of the Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious warfare, amphibious light infantry and also one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighti ...

. The British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

landing force included the 29th Independent Infantry Brigade Group, No 5 (Army) Commando, and two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division, the latter en route to India with the remainder of their division. The Allied naval contingent consisted of over 50 vessels, drawn from Force H, the British Home Fleet and the British Eastern Fleet

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

* Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air L ...

, commanded by Syfret. The fleet included the aircraft carrier '' Illustrious'', her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

'' Indomitable'' and the ageing battleship '' Ramillies'' to cover the landings.

Landings (Operation Ironclad)

Following many reconnaissance missions by theSouth African Air Force

"Through hardships to the stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment ...

, the first wave of the British 29th Infantry Brigade and No. 5 Commando landed in assault craft on 5 May, with follow-up waves by two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division and Royal Marines. All were carried ashore by landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. ...

to Courrier Bay and Ambararata Bay, just west of the major port of Diego-Suarez, at the northern tip of Madagascar. A diversionary attack was staged to the east. Air cover was provided mainly by Fairey Albacore and Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s which attacked Vichy shipping and the airfield at Arrachart. They were supported by Grumman Martlets fighters from the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wi ...

. A small number of SAAF planes assisted. The Swordfish sank the armed merchant cruiser ''Bougainville'' and then the submarine '' Bévéziers,'' although one Swordfish was shot down by anti-aircraft fire and its crew was taken prisoner.Sutherland and Canwell, p. 101 The aircraft shot down had been dropping leaflets in French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

that encouraged the Vichy troops to surrender.

The defending Vichy forces, led by Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy ...

Armand Léon Annet, included about 8,000 troops, of whom about 6,000 were Malagasy tirailleurs ( colonial infantry). A large proportion of the rest were Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

ese. Between 1,500 and 3,000 Vichy troops were concentrated around Diego-Suarez. However, naval and air defences were relatively light and/or obsolete: eight coastal batteries, two armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

s, two sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

, five submarines, 17 Morane-Saulnier 406 fighters and 10 Potez 63

The Potez 630 and its derivatives were a family of twin-engined, multirole aircraft developed for the French Air Force in the late 1930s. The design was a contemporary of the British Bristol Blenheim (which was larger and designed purely as a ...

bombers.

The beach landings met with virtually no resistance and these troops seized Vichy coastal batteries and barracks. The Courier Bay force, the 17th Infantry Brigade, after toiling through

The beach landings met with virtually no resistance and these troops seized Vichy coastal batteries and barracks. The Courier Bay force, the 17th Infantry Brigade, after toiling through mangrove swamp

Mangrove forests, also called mangrove swamps, mangrove thickets or mangals, are productive wetlands that occur in coastal intertidal zones. Mangrove forests grow mainly at tropical and subtropical latitudes because mangroves cannot withstand fre ...

and thick bush took the town of Diego-Suarez taking a hundred prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

. The Ambararata Bay force, the 29th Independent Brigade, headed towards the French naval base of Antisarane. With assistance from six Valentines

Valentine's Day, also called Saint Valentine's Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, is celebrated annually on February 14. It originated as a Christian feast day honoring one or two early Christian martyrs named Saint Valentine and, throu ...

of 'B' Special Service Squadron and six Tetrarch light tanks of 'C' Special Service Squadron they advanced 21 miles overcoming light resistance with bayonet charges.Flint, pp. 68-69 Antisarane itself was heavily defended with trenches, two redoubts, pillboxes, and flanked on both sides by impenetrable swamps.Rigge pp.105-06 Arrachart airfield was attacked, with five of the Morane fighters being destroyed and another two damaged, while two Potez-63s were also damaged. This attack effectively resulted in the Vichy air strength on the island being reduced by 25 per cent. Two Morane fighters did briefly appear and strafe beaches at Courier Bay, but two more Vichy aircraft were lost on the first day.

On the morning of 6 May a frontal assault on the defences failed with the loss of three Valentines and two Tetrarchs. Three Vichy Potez 63s attempted to attack the beach landing points but were intercepted by British Martlets and two were shot down. Albacores were used to bomb French defences, while a Swordfish managed to sink the submarine . By the end of the day fierce resistance had resulted in the destruction 10 out of the 12 tanks the British had brought to Madagascar. The British had been unaware of the strength of the French defences known as the 'Joffre line', and were hugely surprised at the level of resistance they had come across. Another assault by the South Lancashires worked their way around the Vichy defences but the swamps and bad terrain meant they were broken up into groups. Nevertheless, they swung behind the Vichy line and caused chaos. Fire was poured on the Vichy defences from behind and the radio station and a barracks were captured. In all 200 prisoners were taken, but the South Lancashires had to withdraw as communication with the main force was nonexistent after the radio set failed. At this time, the Vichy government in France began to learn of the landings, and Admiral Darlan sent a message to Governor Annet telling him to "Firmly defend the honour of our flag", and "Fight to the limit of your possibilities ... and make the British pay dearly." The Vichy forces then asked for assistance from the Japanese, who were in no position to provide substantial support.

With the Vichy French defence highly effective, the deadlock was broken when the old destroyer dashed straight past the harbour defences of Antisarane and landed fifty Royal Marines from ''Ramillies'' amidst the Vichy rear area. The marines created a "disturbance in the town out of all proportion to their numbers" taking the French artillery command post along with its barracks and the naval depot. At the same time the troops of the 17th Infantry Brigade had broken through the defences and were soon marching in the town. The Vichy defence was broken and Antisarane surrendered that evening, although substantial Vichy forces withdrew to the south. On 7 May British Martlets encountered three Morane French fighters, with one Martlet being shot down. All three of the French fighters were then shot down, meaning that by the third day of the attack on Madagascar, twelve Moranes and five Potez 63s had been destroyed out of a total of 35 Vichy aircraft on the entire island. A further three Potez bombers were destroyed on the ground during a raid on Majunga

Mahajanga (French: Majunga) is a city and an administrative district on the northwest coast of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: Rép ...

on 15 May. Fighting continued into 7 May but by the end of the day Operation ''Ironclad'' had effectively concluded. In just three days of fighting the British had seen 109 men killed and 283 wounded, with the French suffering 700 casualties.

The Japanese submarines , , and arrived three weeks later on 29 May. ''I-10''s reconnaissance plane spotted HMS ''Ramillies'' at anchor in Diego-Suarez harbour, but the plane was spotted and ''Ramillies'' changed her berth. ''I-20'' and ''I-16'' launched two midget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

s, one of which managed to enter the harbour and fired two torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, ...

es while under depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive hydraulic shock. Most depth charges use h ...

attack from two corvettes. One torpedo seriously damaged ''Ramillies'', while the second sank the 6,993-ton oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk transport of oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quantities of unrefined ...

''British Loyalty'' (later refloated).Rigge pp. 107–108 ''Ramillies'' was later repaired in Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

.

The crew of one of the midget submarines, Lieutenant Saburo Akieda and Petty Officer Masami Takemoto, beached their craft (''M-20b'') at Nosy Antalikely and moved inland towards their pick-up point near Cape Amber. They were betrayed when they bought food at the village of Anijabe and both were killed in a firefight with Royal Marines three days later. One marine was killed in the action as well. The second midget submarine was lost at sea and the body of a crewman was found washed ashore a day later.

Ground campaign (Operation Stream Line Jane)

Hostilities continued at a low level for several months. After 19 May two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division were transferred to India. On 8 June, the 22nd (East Africa) Brigade Group arrived on Madagascar. The 7th South African Motorized Brigade arrived on 24 June. On 2 July, an invasion force was sent to the Vichy-held island of

Hostilities continued at a low level for several months. After 19 May two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division were transferred to India. On 8 June, the 22nd (East Africa) Brigade Group arrived on Madagascar. The 7th South African Motorized Brigade arrived on 24 June. On 2 July, an invasion force was sent to the Vichy-held island of Mayotte

Mayotte (; french: Mayotte, ; Shimaore: ''Maore'', ; Kibushi: ''Maori'', ), officially the Department of Mayotte (french: Département de Mayotte), is an overseas department and region and single territorial collectivity of France. It is loca ...

in order to take control of its valuable radio station and to utilise it as a useful base for British operations in the area. The island's defenders were caught by surprise and the key radio station and most of the sleeping defenders were captured. The Chief of Police and a few others attempted to escape by car but were stopped by roadblocks that had been assembled. The island's capture was carried out with no loss of life or major damage.

The 27th (North Rhodesia) Infantry Brigade (including forces from East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

) landed in Madagascar on 8 August. The Vichy governor of Madagascar Annet attempted to obtain reinforcements from the central Vichy government, particularly in terms of aircraft, but was unable to do so. By August, Vichy air strength on the island primarily consisted of only four Morane fighters and three Potez-63s.

The operation code-named "Stream Line Jane" (sometimes given as "Streamline Jane") consisted of three separate sub-operations code-named Stream, Line and Jane. Stream and Jane were, respectively, the amphibious landings at Majunga on 10 September and Tamatave on 18 September, while Line was the advance from Majunga to the French capital, Tananarive

Antananarivo ( French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "An ...

, which fell on 23 September.

On 10 September the 29th Brigade and 22nd Brigade Group made an amphibious landing at Majunga, another port on the west coast of the island. No. 5 Commando spearheaded the landing and faced machine gun fire but despite this they stormed the quayside, took control of the local post office, stormed the governor's residence and raised the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

. Having severed communications with Tananarive, the Allies intended to re-launch the offensive ahead of the rainy season

The rainy season is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs.

Rainy Season may also refer to:

* ''Rainy Season'' (short story), a 1989 short horror story by Stephen King

* "Rainy Season", a 2018 song by Monni

* '' ...

. Progress was slow for the Allied forces. In addition to occasional small-scale clashes with Vichy forces, they also encountered scores of obstacles erected on the main roads by Vichy soldiers. Vichy forces attempted to destroy the second bridge on the Majunga-Tananarive road, but only succeeded in causing the central span of the bridge to sag merely 3 ft into the river below, meaning that Allied vehicles could still pass over. Once the Vichy forces realised their mistake, a Potez-63 aircraft was sent to drop bombs to finish off the bridge, but the attack failed. The Allies eventually captured the capital, Tananarive

Antananarivo ( French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "An ...

, without much opposition, and then the town of Ambalavao

Ambalavao is a city (''commune urbaine'') in Madagascar, in the Haute Matsiatra region. The city is in the most southern part of the Central Highlands, near the city of Fianarantsoa.

Nature

*The Anja Community Reserve, situated about 13 ...

, but the devoutly Vichy Governor Annet escaped.Rigge pp 110-11

Eight days later a British force set out to capture Tamatave. Heavy surf interfered with the operation. As HMS ''Birmingham''s launch was heading to shore it was fired at by French shore batteries and promptly turned around. ''Birmingham'' then opened her guns up on the shores batteries and within three minutes the French hauled up the white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symbolize ...

and surrendered. From there the South Lancashires and the Royal Welch Fusiliers set out to the south to link up with forces there. After they reached Tananarive they pressed on towards Moramanga and on 25 September they linked up with the King's African Rifles having secured the British lines of communication around the island. At the same time the East African infantry and South African armoured cars set out to find the elusive Governor Annet. The same day, a bombing raid was launched by South African Marylands on a Vichy-held fort in Fianarantsoa

Fianarantsoa is a city (commune urbaine) in south central Madagascar, and is the capital of Haute Matsiatra Region.

History

It was built in the early 19th century by the Merina as the administrative capital for the newly conquered Betsileo kin ...

, the only major centre of population that was still in French hands and where the remainder of the Vichy aircraft were now based. Tetrarch and Valentine tanks of 'B' and 'C' Special Service Squadrons had been embarked for use in these operations, but they were not used as they could not ford the Ivondro River and the railway bridges were unsuitable.

On 29 September, two companies of the South African Pretoria Highlanders performed the only amphibious landing by South African forces of the entire war at the west coast harbor town of Tulear

Toliara (also known as ''Toliary'', ; formerly ''Tuléar'') is a city in Madagascar.

It is the capital of the Atsimo-Andrefana region, located 936 km southwest of national capital Antananarivo.

The current spelling of the name was adopted ...

some 900 miles south of Diego Suarez. HMS ''Birmingham'', 2 destroyers and 200 Royal Marines supported the unopposed landing.

On 6 October, a Morane fighter strafed British positions near Antinchi, and on 8 October a British bombing raid on Ihosy

Ihosy is a city (commune urbaine) with 283,047 inhabitants (2015) in Ihorombe Region in central south Madagascar.

Ihosy is the capital of Ihorombe Region, as well as of the district of Ihosy.

Geography

Ihosy is an important crosspoint for ...

airfield destroyed four Vichy aircraft.

The last major action took place on 18 October, at Andramanalina, a U-shaped valley with the meandering Mangarahara River where an ambush was planned for British forces by Vichy troops. The King's African Rifles split into two columns and marched around the 'U' of the valley and met Vichy troops in the rear and then ambushed them. The Vichy troops suffered heavy losses which resulted in 800 of them surrendering. A single Morane fighter was operational until 21 October, and even strafed South African troops, but by 21 October the only serviceable aircraft the Vichy forces had was a Salmson Phrygane transport aircraft. On 25 October the King's African Rifles entered Fianarantsoa

Fianarantsoa is a city (commune urbaine) in south central Madagascar, and is the capital of Haute Matsiatra Region.

History

It was built in the early 19th century by the Merina as the administrative capital for the newly conquered Betsileo kin ...

but found Annet gone, this time near Ihosy

Ihosy is a city (commune urbaine) with 283,047 inhabitants (2015) in Ihorombe Region in central south Madagascar.

Ihosy is the capital of Ihorombe Region, as well as of the district of Ihosy.

Geography

Ihosy is an important crosspoint for ...

100 miles south. The Africans swiftly moved after him, but they received an envoy from Annet asking for terms of surrender. He had had enough and couldn't escape further. An armistice was signed in Ambalavao

Ambalavao is a city (''commune urbaine'') in Madagascar, in the Haute Matsiatra region. The city is in the most southern part of the Central Highlands, near the city of Fianarantsoa.

Nature

*The Anja Community Reserve, situated about 13 ...

on 6 November, and Annet surrendered two days later.

The Allies suffered about 500 casualties in the landing at Diego-Suarez, and 30 more killed and 90 wounded in the operations which followed on 10 September 1942.

Julian Jackson, in his biography of de Gaulle, observed that the French had held out longer against the Allies in Madagascar in 1942 than they had against the Germans in France in 1940.

Aftermath

With Madagascar in their hands, the Allies established military and naval installations across the island. The island was crucial for the rest of the war. Its deep water ports were vital for control of the passageway to India and the Persian corridor, and were now beyond the grasp of the Axis. This was the first large-scale operation of World War II by the Allies combining sea, land, and air forces. In the makeshift Allied planning of the war's early years, the invasion of Madagascar held a prominent strategic place.

Historian John Grehan has claimed that the British capture of Madagascar before it could fall into Japanese hands was so crucial in the context of the war that it led to Japan's eventual downfall and defeat.

Free French General

With Madagascar in their hands, the Allies established military and naval installations across the island. The island was crucial for the rest of the war. Its deep water ports were vital for control of the passageway to India and the Persian corridor, and were now beyond the grasp of the Axis. This was the first large-scale operation of World War II by the Allies combining sea, land, and air forces. In the makeshift Allied planning of the war's early years, the invasion of Madagascar held a prominent strategic place.

Historian John Grehan has claimed that the British capture of Madagascar before it could fall into Japanese hands was so crucial in the context of the war that it led to Japan's eventual downfall and defeat.

Free French General Paul Legentilhomme

Paul Louis Legentilhomme (March 26, 1884 – May 23, 1975) was an officer in the French Army during World War I and World War II. After the fall of France in 1940, he joined the forces of the Free French. Legentilhomme was a recipient of the ...

was appointed High Commissioner for Madagascar in December 1942 only to replace British administration. Like many colonies, Madagascar sought its independence from the French Empire following the war. In 1947, the island experienced the Malagasy Uprising

The Malagasy Uprising (french: Insurrection malgache; mg, Tolom-bahoaka tamin' ny 1947) was a Malagasy nationalist rebellion against French colonial rule in Madagascar, lasting from March 1947 to February 1949. Starting in late 1945, Madagasca ...

, a costly revolution that was crushed in 1948. It was not until 26 June 1960, about twelve years later, that the Malagasy Republic

The Malagasy Republic ( mg, Repoblika Malagasy, french: République malgache) was a state situated in Southeast Africa. It was established in 1958 as an autonomous republic within the newly created French Community, became fully independent i ...

successfully proclaimed its independence from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

Campaign service in Madagascar did not qualify for the British and Commonwealth Africa Star

The Africa Star is a military campaign medal, instituted by the United Kingdom on 8 July 1943 for award to British and Commonwealth forces who served in North Africa between 10 June 1940 and 12 May 1943 during the Second World War.

Three clasp ...

. It was instead covered by the 1939–1945 Star

The 1939–1945 Star is a military campaign medal instituted by the United Kingdom on 8 July 1943 for award to British and Commonwealth forces for service in the Second World War. Two clasps were instituted to be worn on the medal ribbon, Batt ...

.

Order of battle

Allied Forces

Naval forces

Royal Naval Commandos

The Royal Naval Commandos, also known as RN Beachhead Commandos, were a commando formation of the Royal Navy which served during the Second World War. The first units were raised in 1942 and by the end of the war, 22 company-sized units had been r ...

:Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious warfare, amphibious light infantry and also one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighti ...

Ground forces

;29th Infantry Brigade (independent) arrived via amphibious landing near Diego-Suarez on 5 May 1942

:2nd South Lancashire Regiment

:2nd East Lancashire Regiment

:1st

;29th Infantry Brigade (independent) arrived via amphibious landing near Diego-Suarez on 5 May 1942

:2nd South Lancashire Regiment

:2nd East Lancashire Regiment

:1st Royal Scots Fusiliers

The Royal Scots Fusiliers was a line infantry regiment of the British Army that existed from 1678 until 1959 when it was amalgamated with the Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Regiment) to form the Royal Highland Fusiliers (Princess Ma ...

:2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers

The Royal Welch Fusiliers ( cy, Ffiwsilwyr Brenhinol Cymreig) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, and part of the Prince of Wales' Division, that was founded in 1689; shortly after the Glorious Revolution. In 1702, it was designate ...

:455th Light Battery (Royal Artillery)

:MG company

:'B' Special Service Squadron with 6 Valentine

:'C' Special Service Squadron with 6 Tetrarch tanks

;Commandos arrived via amphibious landing near Diego-Suarez on 5 May 1942

: No. 5 Commando

;British 17th Infantry Brigade Group (of 5th Division) landed near Diego-Suarez as second wave on 5 May 1942

:2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers

:2nd Northamptonshire Regiment

:6th Seaforth Highlanders

:9th Field Regiment (Royal Artillery)

;British 13th Infantry Brigade (of 5th Division) landed near Diego-Suarez as third wave on 6 May 1942. Departed 19 May 1942 for India

:2nd Cameronians

:2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

:2nd Wiltshire Regiment

The Wiltshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 62nd (Wiltshire) Regiment of Foot and the 99th Duke of Edinburgh's (Lanarkshire) Regiment of Foot.

The ...

;East African Brigade Group arrived 22 June to replace 13 and 17 Brigades

; South African 7th Motorised Brigade

; Rhodesian 27th Infantry Brigade arrived 8 August 1942; departed 29 June 1944

:2nd Northern Rhodesia Regiment

The Northern Rhodesia Regiment (NRR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from the protectorate of Northern Rhodesia. It was formed in 1933 from elements of the Northern Rhodesia Police, which had been formed during Company ...

:3rd Northern Rhodesia Regiment

:4th Northern Rhodesia Regiment

:55th (Tanganyika) Light Battery

:57th (East African) Field Battery

Fleet Air Arm

;Aboard HMS ''Illustrious'' :881 Squadron - 12 Grumman Martlet Mk.II :882 Squadron - 8 Grumman Martlet Mk.II, 1 Fairey Fulmar :810 Squadron - 10Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

:829 Squadron - 10 Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

;Aboard HMS ''Indomitable''

:800 Squadron - 8 Fairey Fulmar

The Fairey Fulmar is a British carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraft/fighter aircraft which was developed and manufactured by aircraft company Fairey Aviation. It was named after the northern fulmar, a seabird native to the British Isles. The F ...

:806 Squadron - 4 Fairey Fulmar

The Fairey Fulmar is a British carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraft/fighter aircraft which was developed and manufactured by aircraft company Fairey Aviation. It was named after the northern fulmar, a seabird native to the British Isles. The F ...

:880 Squadron - 6 Hawker Sea Hurricane Mk IA

:827 Squadron - 12 Fairey Albacore

:831 Squadron - 12 Fairey Albacore

Vichy France

Naval forces

:Merchant Cruiser

:Sloop

;Submarines

:

:

:

:Merchant Cruiser

:Sloop

;Submarines

:

:

:

Land forces

The following order of battle represents the Malagasy and Vichy French forces on the island directly after the initial ''Ironclad'' landings. ;West coast

:Two platoons of reservists and volunteers at Nossi-Bé

:Two companies of the ''Régiment mixte malgache'' (RMM – Mixed Madagascar Regiment) at

;West coast

:Two platoons of reservists and volunteers at Nossi-Bé

:Two companies of the ''Régiment mixte malgache'' (RMM – Mixed Madagascar Regiment) at Ambanja

Ambanja is a city and commune in northern Madagascar. According to 2001 census the population of Ambanja was 28,468.

Geography

Ambanja is located on the northern berth of the Sambirano River and is crossed by the Route Nationale 6 (Antsiranan ...

:One battalion of the 1er RMM at Majunga

Mahajanga (French: Majunga) is a city and an administrative district on the northwest coast of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: Rép ...

;East coast

:One battalion of the 1er RMM at Tamatave

Toamasina (), meaning "like salt" or "salty", unofficially and in French Tamatave, is the capital of the Atsinanana region on the east coast of Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. The city is the chief seaport of the country, situated northeast of it ...

:One artillery section (65mm) at Tamatave

:One company of the 1er RMM at Brickaville

;Centre of the island

:Three battalions of the 1er RMM at Tananarive

Antananarivo ( French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "An ...

:One motorised reconnaissance detachment at Tananarive

:Emyrne battery at Tananarive

:One artillery section (65mm) at Tananarive

:One engineer company at Tananarive

:One company of the 1er RMM at Mevatanana

:One company of the ''Bataillon de tirailleurs malgaches'' (BTM - Malagasy Tirailleurs Battalion) at Fianarantsoa

Fianarantsoa is a city (commune urbaine) in south central Madagascar, and is the capital of Haute Matsiatra Region.

History

It was built in the early 19th century by the Merina as the administrative capital for the newly conquered Betsileo kin ...

:South of the island

;Other

:One company of the BTM at Fort Dauphin

:One company of the BTM at Tuléar

Toliara (also known as ''Toliary'', ; formerly ''Tuléar'') is a city in Madagascar.

It is the capital of the Atsimo-Andrefana region, located 936 km southwest of national capital Antananarivo.

The current spelling of the name was adopted ...

Japan

Naval forces

* Submarines ''I-10

Interstate 10 (I-10) is the southernmost cross-country highway in the American Interstate Highway System. I-10 is the fourth-longest Interstate in the United States at , following I-90, I-80, and I-40. This freeway is part of the originally p ...

'' (with reconnaissance aircraft), ''I-16 I16 may refer to:

* Interstate 16, an interstate highway in the U.S. state of Georgia

* Polikarpov I-16, a Soviet fighter aircraft introduced in the 1930s

* Halland Regiment

* , a Japanese Type C submarine

* i16, a name for the 16-bit signed integ ...

'', ''I-18'' (damaged by heavy seas and arrived late), ''I-20

Interstate 20 (I‑20) is a major east–west Interstate Highway in the Southern United States. I-20 runs beginning at an interchange with I-10 in Scroggins Draw, Texas, and ending at an interchange with I-95 in Florence, South Carolina. Betwe ...

''

* Midget submarines ''M-16b'', ''M-20b''

See also

*Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

* Madagascar in World War II

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

exordio.com, ?, "Operación Ironclad" (Spanish language)

''BBC History'' magazine podcast about the Battle of Madagascar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Madagascar 1942, Battle Of Battles of World War II involving Japan Land battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Battles and operations of World War II involving South Africa Conflicts in 1942 History of Madagascar Military battles of Vichy France World War II occupied territories 1942 in France 1942 in Madagascar Amphibious operations of World War II Amphibious operations involving the United Kingdom