Battle of Kip's Bay on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Landing at Kip's Bay was a

On September 5, General

On September 5, General

On September 10, British troops moved from Long Island to occupy Montresor's Island, a small island at the mouth of the

On September 10, British troops moved from Long Island to occupy Montresor's Island, a small island at the mouth of the

Admiral Howe sent a noisy demonstration of

Admiral Howe sent a noisy demonstration of  General Putnam had come north with some of his troops when the landing began. After briefly conferring with Washington about the risk of entrapment to his forces in the city, he rode south to lead their retreat. Abandoning supplies and equipment that would slow them down, his column, under the guidance of his aide

General Putnam had come north with some of his troops when the landing began. After briefly conferring with Washington about the risk of entrapment to his forces in the city, he rode south to lead their retreat. Abandoning supplies and equipment that would slow them down, his column, under the guidance of his aide

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

amphibious landing

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

during the New York Campaign

The New York and New Jersey campaign in 1776 and the winter months of 1777 was a series of American Revolutionary War battles for control of the Port of New York and the state of New Jersey, fought between British forces under General Sir Will ...

in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

on September 15, 1776. It occurred on the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

shore of Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

north of what then constituted New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

Heavy advance fire from British naval forces in the East River caused the inexperienced militia guarding the landing area to flee, allowing the British to land unopposed at Kip's Bay

Kips Bay, or Kip's Bay, is a neighborhood on the east side of the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is roughly bounded by 34th Street (Manhattan), East 34th Street to the north, the East River to the east, East 27th and/or 23rd Streets to th ...

. Skirmishes in the aftermath of the landing resulted in the British capture of some of those militia. British maneuvers following the landing very nearly cut off the escape route of some Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

forces stationed further southeast on the island. The flight of American troops was so rapid that George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, who was attempting to rally them, was left exposed dangerously close to British lines.

The operation was a British success. It forced the Continental Army to withdraw to Harlem Heights, ceding control of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on the lower half of the island. However, General Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of t ...

established strong positions on Harlem Heights, which he defended in a fierce skirmish between the two armies the following day. General Howe, unwilling to risk a costly frontal attack, did not attempt to advance further up the island for another two months.

Background

TheAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

had not gone well for the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

military in 1775 and early 1776. At besieged Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, the arrival of heavy guns for the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

camp prompted General William Howe

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, KB PC (10 August 172912 July 1814) was a British Army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British land forces in the Colonies during the American War of Independence. Howe was one of three brot ...

to withdraw from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. Th ...

in March 1776. He regrouped there, acquired supplies and reinforcements, and embarked in June on a campaign to gain control of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Anticipating that the British would next attack New York, General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

moved his army there to assist General Putnam in the defensive preparations, a task complicated by the large number of potential landing sites for a British force.

Howe's troops began an unopposed landing on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

in early July, and made another unopposed landing on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

, where Washington's Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

had organized significant defenses, on August 22. On August 27, Howe successfully flanked Washington's defenses in the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yor ...

, leaving Washington in a precarious position on the narrow Brooklyn Heights, with the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

in front and the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

behind him. On the night of August 29–30, Washington successfully evacuated his entire army of 9,000 troops to York Island (as Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

was then known).

Despite showing discipline and unity during the evacuation, the army quickly devolved in despair and anger. Large numbers of militia, many of whose summertime enlistments ended in August, departed for home. Leadership was questioned in the ranks, with soldiers openly wishing for the return of the colorful and charismatic General Charles Lee. Washington sent a missive to the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

asking for some direction—specifically, if New York City, which then occupied only the southern tip of Manhattan Island, should be abandoned and burned to the ground. "They would derive great conveniences from it, on the one hand, and much property would be destroyed on the other," Washington wrote.

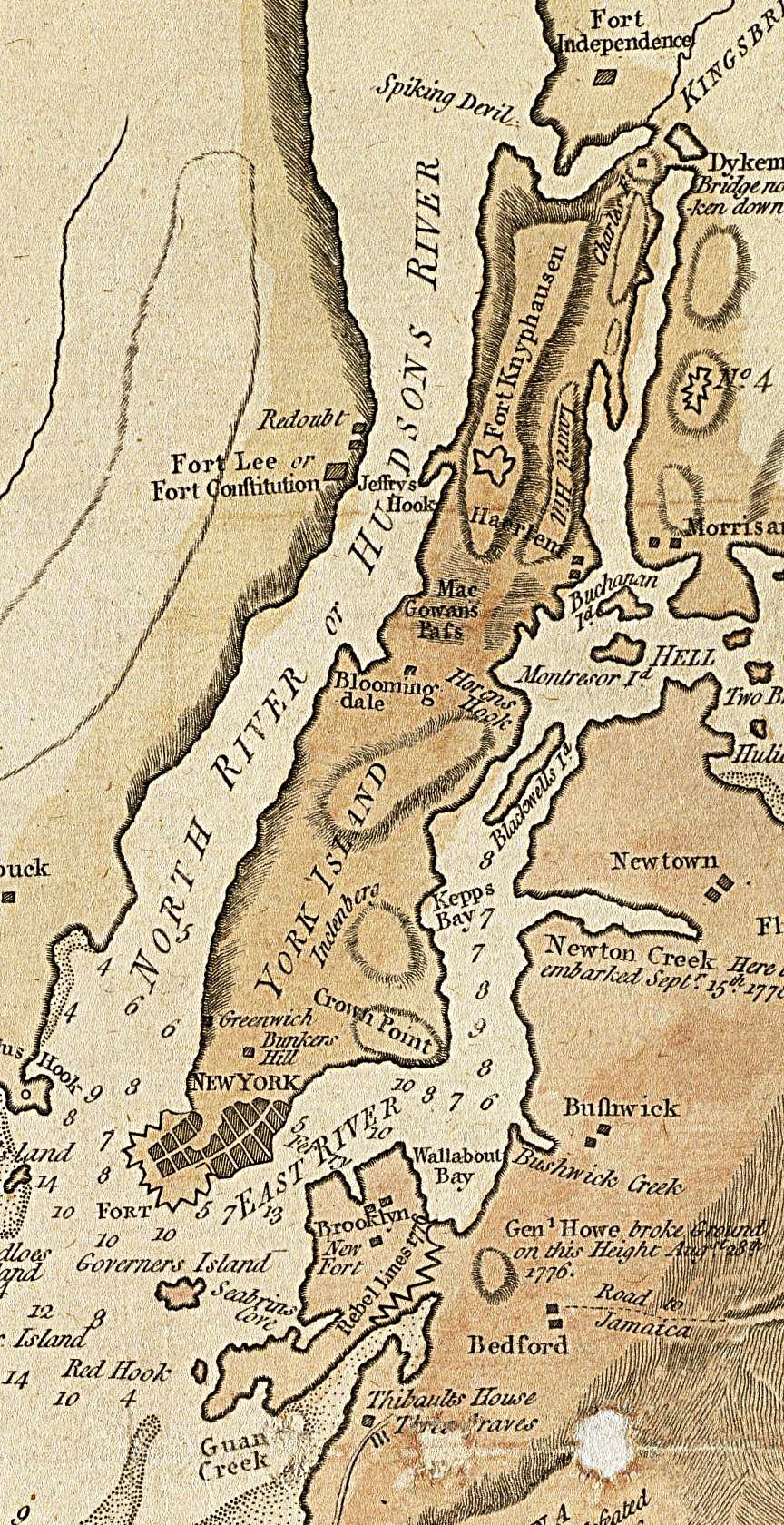

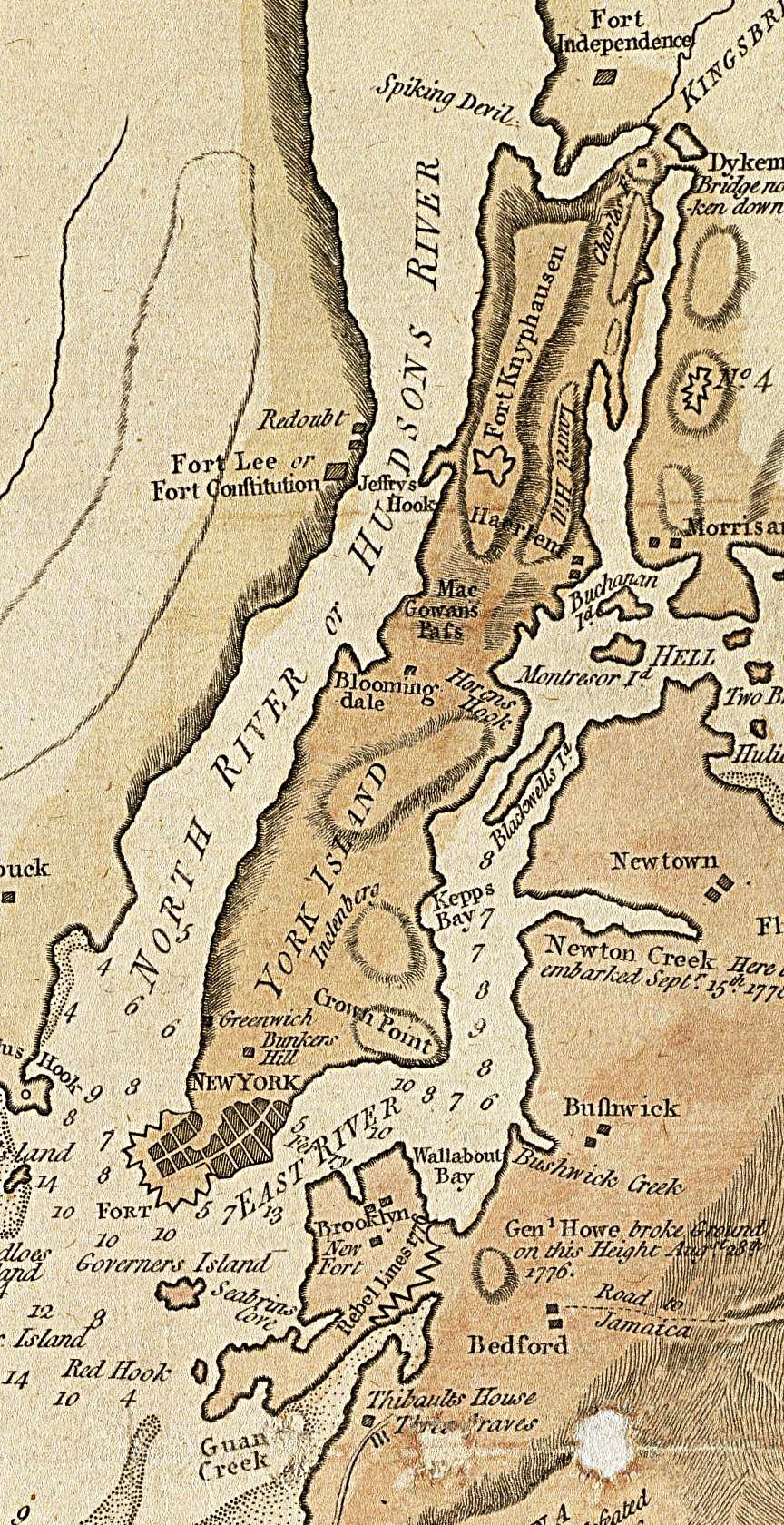

Geography

York Island was occupied principally on the southern tip (now Lower Manhattan) by New York City, on the western tip byGreenwich village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, and in the north by the village of Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

. The sparsely-populated center of the island featured a few low hills, principally Indianburg and Crown Heights. Ferry services connected the island to the surrounding lands, with the primary ferry to the mainland of Westchester County

Westchester County is located in the U.S. state of New York. It is the seventh most populous county in the State of New York and the most populous north of New York City. According to the 2020 United States Census, the county had a population ...

(now the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New ...

) crossing the Harlem River

The Harlem River is an tidal strait in New York, United States, flowing between the Hudson River and the East River and separating the island of Manhattan from the Bronx on the New York mainland.

The northern stretch, also called the Spuyt ...

at King's Bridge near the northern tip of the island. The island was bordered by two rivers, on the west by the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

and on the east by the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

, which separated the island from Long Island. Kip's Bay

Kips Bay, or Kip's Bay, is a neighborhood on the east side of the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is roughly bounded by 34th Street (Manhattan), East 34th Street to the north, the East River to the east, East 27th and/or 23rd Streets to th ...

was a cove on the eastern shore of the island, extending roughly from present-day 32nd to 38th Streets, and as far west as Second Avenue. The bay no longer exists as such, having been filled in, but in 1776, it provided an excellent place for an amphibious landing: deep water close to the shore, and a large meadow for mustering landed troops. Opposite the bay on Long Island, the wide mouth of Newtown Creek

Newtown Creek, a long tributary of the East River, is an estuary that forms part of the border between the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, in New York City. Channelization made it one of the most heavily-used bodies of water in the Port of N ...

, also surrounded by meadowlands, offered an equally excellent staging area.

Planning

Washington, uncertain of General Howe's next step, spread his troops thinly along the shores of York Island and the Westchester shore, and actively sought intelligence that would yield clues to Howe's plans. He also ordered an attempt against , the flagship of General Howe's brother and commander of theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

at New York, Admiral Richard Howe

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations a ...

. On September 7, in the first documented case of submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

warfare, Sergeant Ezra Lee volunteered to pilot the submersible to ''Eagle'' and attach explosives to the ship; the submersible's drill struck an iron band it could not penetrate, and Lee was unable to attach the required explosives. Lee was able to escape, although he was forced to release his explosive payload to fend off small boats sent by the British to investigate when he surfaced to orient himself. The payload exploded harmlessly in the East River.

Meanwhile, British troops, led by General Howe, were moving north up the east shore of the East River, towards King's Bridge. During the night of September 3 the British frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

took advantage of a north-flowing tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

and, towing thirty flatboats

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with a ...

, moved up the East River and anchored in the mouth of Newtown Creek. The next day, more transports and flatboats moved up the East River. Three warships—, and —along with the schooner HMS ''Tryal'', sailed into the Hudson.

On September 5, General

On September 5, General Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

, recently returned to duty from a serious illness, sent Washington a letter urging an immediate withdrawal from New York. Without possession of Long Island, Greene argued, New York City could not be held. With the army scattered in encampments on York Island, the Americans would not be able to stop a British attack. Another decisive defeat, he argued, would be catastrophic with regard to the loss of men and the damage to morale. He also recommended burning the city; once the British had control, it could never be recovered without a comparable or superior naval force. There was no American benefit to preserving New York City, Greene summarized, and recommended that Washington convene a war council. By the time the council was gathered on September 7, however, a letter had arrived from John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor o ...

stating Congress's resolution that although New York should not be destroyed, Washington was not required to defend it. Congress had also decided to send a three-man delegation to confer with Lord Howe—John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

, and Edward Rutledge

Edward Rutledge (November 23, 1749 – January 23, 1800) was an American Founding Father and politician who signed the Continental Association and was the youngest signatory of the Declaration of Independence. He later served as the 39th gov ...

.

Preparations

Harlem River

The Harlem River is an tidal strait in New York, United States, flowing between the Hudson River and the East River and separating the island of Manhattan from the Bronx on the New York mainland.

The northern stretch, also called the Spuyt ...

. One day later, on September 11, the Congressional delegation arrived on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

and met with Admiral Lord Howe for several hours. The meeting came to nothing, as Lord Howe was not authorized to grant terms the Congressional delegation insisted on. It did, however, postpone the impending British attack, allowing Washington more time to decide if and where to confront the enemy.

In a September 12 war council, Washington and his generals made the decision to abandon New York City. Four thousand Continentals under General Israel Putnam remained to defend the city and lower Manhattan while the main army moved north to Harlem and King's Bridge. On the afternoon of September 13, major British movement started as the warships and ''Phoenix'', along with the frigates ''Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

'' and ''Carysfort'', moved up the East River and anchored in Bushwick Creek

Bushwick Inlet Park is a public park in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City. The park currently consists of two non-contiguous sections along the East River and is eventually planned to reach into Greenpoint at Quay Stre ...

, carrying 148 total cannons and accompanied by six troop transport ships. By September 14 the Americans were urgently moving stores of ammunition

Ammunition (informally ammo) is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. Ammunition is both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines) and the component parts of other we ...

and other materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

, along with American sick, to Orangetown, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.Fischer, ''Washington's Crossing'', p. 102 Every available horse and wagon was employed in what Joseph Reed described as a "grand military exertion". Scouts reported movement in the British army camps but Washington was still uncertain where the British would strike. Late that afternoon, most of the American army had moved north to King's Bridge and Harlem Heights, and Washington followed that night.McCullough, ''1776'', pp. 208–209

General Howe had originally planned a landing for September 13, recalling the date of James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. ...

's key landing before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

in 1759. He and General Clinton disagreed on the point of attack, with Clinton arguing that a landing at King's Bridge would have cut Washington off once and for all. Howe originally wanted to make two landings, one at Kip's Bay and another at Horn's Hook, further north (near modern 90th Street) on the eastern shore. He struck the latter option when ship's pilots warned of the dangerous waters of the Hell Gate

Hell Gate is a narrow tidal strait in the East River in New York City. It separates Astoria, Queens, from Randall's and Wards Islands.

Etymology

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of the Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'' (it first appeared on ...

, where the Harlem River and waters of Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is a marine sound and tidal estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It lies predominantly between the U.S. state of Connecticut to the north and Long Island in New York to the south. From west to east, the sound stretches from the Eas ...

meet the East River. After delays due to unfavorable winds, the landing, targeted for Kip's Bay, began on the morning of September 15.

Landing

Admiral Howe sent a noisy demonstration of

Admiral Howe sent a noisy demonstration of Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

ships up the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

early on the morning of September 15, but Washington and his aides determined that it was a diversion and maintained their forces at the north end of the island. Five hundred Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

under the command of Colonel William Douglas had erected a crude breastwork on the American line at Kip's Bay, but many of these farmers and shopkeepers were inexperienced and had no muskets. They carried instead homemade pikes constructed of scythe

A scythe ( ) is an agriculture, agricultural hand tool for mowing grass or Harvest, harvesting Crop, crops. It is historically used to cut down or reaping, reap edible grain, grains, before the process of threshing. The scythe has been largely ...

blades attached to poles. After having been awake all night, and having had little or nothing to eat in the previous twenty-four hours, at dawn they looked over their meager redoubt

A redoubt (historically redout) is a fort or fort system usually consisting of an enclosed defensive emplacement outside a larger fort, usually relying on earthworks, although some are constructed of stone or brick. It is meant to protect soldi ...

to see five British warships

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster an ...

in the East River near their position. As the militia at Kip's Bay lay in their ditches, the British ships, anchored offshore, also lay quiet. The day was oppressively hot. At about 10 am, General Sir Henry Clinton, to whom Howe had given the task of making the landing, ordered the crossing to begin. A first wave of more than eighty flatboats carried 4,000 British and Hessian soldiers, standing shoulder to shoulder, left Newtown Cove and entered the waters of the East River, heading towards Kip's Bay.

Around eleven, the five warships began a salvo of broadside fire that flattened the flimsy American breastworks and panicked the Connecticut militia. "So terrible and so incessant a roar of guns few even in the army and navy had ever heard before," wrote Ambrose Serle

Ambrose Serle (1742–1812) was an English official, diarist and writer of Christian prose and hymns.

Life

Serle was born on 30 August 1742, and entered the Royal Navy. In 1764, while living in or near London, Serle became a friend of William Ro ...

, private secretary to Lord Howe. Nearly eighty guns fired at the shore for a full hour. The Americans were half buried under dirt and sand, and were unable to return fire due to the smoke and dust. After the guns ceased, the British flatboats appeared out of the smoke and headed for shore. By then the Americans were in a panicked retreat, and the British began their amphibious landing

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

.

Although Washington and his aides arrived from the command post at Harlem Heights soon after the landing began, they were unable to rally the retreating militia. About a mile (1.6 km) inland from Kip's Bay, Washington rode his horse among the men, trying to turn them around and impose some order on them, cursing furiously and violently. By some accounts, he lost control of his temper; he brandished a cocked pistol and drew his sword, threatening to run men through and shouted, "Take the walls! Take the cornfield!" When no one obeyed, he threw his hat to the ground, exclaiming in disgust, "Are these the men with which I am to defend America?"McCullough, ''1776'', p. 212 When some fleeing men refused to turn and engage a party of advancing Hessians, Washington reportedly struck some of their officers with his riding crop. The Hessians shot or bayoneted a number of American troops who were trying to surrender. Two thousand Continental Army troops under the command of Generals Samuel Parsons

Samuel Bowne Parsons Jr. (8 February 1844 – 3 February 1923), was an American landscape architect. He is remembered as being a founder of the American Society of Landscape Architects, helping to establish the profession.

Early years

Parsons w ...

and John Fellows arrived from the north, but at the sight of the chaotic militia retreat, they also turned and fled. Washington, still in a rage, rode within a hundred yards of the enemy, "stupefied, immobilized by his seething fury, was heedless. One of his men grabbed the reins of his horse and hurried Washington to a safer place."

More and more British soldiers came ashore, including light infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

, grenadiers

A grenadier ( , ; derived from the word ''grenade'') was originally a specialist soldier who threw hand grenades in battle. The distinct combat function of the grenadier was established in the mid-17th century, when grenadiers were recruited from ...

, and Hessian Jägers. They spread out, advancing in several directions. By late afternoon another 9,000 British troops had landed at Kip's Bay, and Howe had sent a brigade toward New York City, officially taking possession. While most of the Americans managed to escape to the north, not all got away. "I saw a Hessian sever a rebel's head from his body and clap it on a pole in the entrenchments," recorded a British officer. The southern advance pushed for a half mile (0.8 km) to Watts farm (near present-day 23rd Street) before meeting stiff American resistance. The northern advance stopped at the Inclenberg (now Murray Hill, a rise west of Kip's Bay), just west of the present Lexington Avenue

Lexington Avenue, often colloquially abbreviated as "Lex", is an avenue on the East Side of the borough of Manhattan in New York City that carries southbound one-way traffic from East 131st Street to Gramercy Park at East 21st Street. Along i ...

, under orders from General Howe to wait for the rest of the invading force. This was extremely fortunate for the thousands of American troops south of the invasion point. Had Clinton continued west to the Hudson he would have cut off General Putnam's troops, nearly one third of Washington's forces, from the main army, trapping them in lower Manhattan.

General Putnam had come north with some of his troops when the landing began. After briefly conferring with Washington about the risk of entrapment to his forces in the city, he rode south to lead their retreat. Abandoning supplies and equipment that would slow them down, his column, under the guidance of his aide

General Putnam had come north with some of his troops when the landing began. After briefly conferring with Washington about the risk of entrapment to his forces in the city, he rode south to lead their retreat. Abandoning supplies and equipment that would slow them down, his column, under the guidance of his aide Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

, marched north along the Hudson. The forced march of Putnam's men was so quick, and the British advance sufficiently slow, that only the last companies in Putnam's column skirmished with the advancing British. When Putnam and his men marched into the main camp at Harlem after dark, they were greeted by cheers, having been given up for lost. Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following th ...

arrived later after a narrow escape made possible by seizing a boat on the Hudson and he too received an excited and enthusiastic greeting, and was even embraced by Washington.

Aftermath

The British were welcomed by the remaining New York City population, pulling down the Continental Army flag and raising theUnion Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

. Howe, who had wanted to capture New York quickly and with minimal bloodshed, considered the invasion a complete success. Not wanting to continue battling with the Americans that day, Howe stopped his troops short of Harlem.

Washington was extremely angry with his troops' conduct, calling their actions "shameful" and "scandalous". The Connecticut militia, who already had a poor reputation, were labeled cowards and held to blame for the rout. However, others were more circumspect, such as General William Heath, who said, "The wounds received on Long Island were yet bleeding; and the officers, if not the men, knew that the city was not to be defended." If the Connecticut men would have stayed to defend York Island under the withering cannon fire and in the face of overwhelming force, they would have been annihilated.McCullough, ''1776'', pp. 214–215

The next day, September 16, there was further fighting when a clash of outposts escalated into a running battle below Washington's lines on Harlem Heights.McCullough, ''1776'', p. 216 After several hours exchange of musketry, the forces engaged returned to their start lines, and the position of the two armies on Manhattan remained relatively unchanged for the next two months. Having held their own against picked British troops, the American army received a much needed boost to their morale after the debâcle of the previous day, while the British acquired a renewed respect for the American ability to stand and fight.

See also

* American Revolutionary War §British New York counter-offensive. The ‘Landing at Kip’s Bay’ placed in overall sequence and strategic context.Notes

References

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kip's Bay Battles of the New York Campaign Conflicts in 1776 1776 in the United States Battles involving Great Britain Battles involving the United States Battles involving Hesse-Kassel Landing operations