Battle of Kinburn (1855) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Kinburn, a combined land-naval engagement during the final stage of the

The fortress was located on the Kinburn Spit, at the extreme western end of the Kinburn Peninsula, and consisted of three separate fortifications. The primary fort, built of stone, square, and equipped with

The fortress was located on the Kinburn Spit, at the extreme western end of the Kinburn Peninsula, and consisted of three separate fortifications. The primary fort, built of stone, square, and equipped with

In an effort to confuse the Russians, the combined fleet made a feint westward toward

In an effort to confuse the Russians, the combined fleet made a feint westward toward

On 20 October, Bazaine's infantry conducted reconnaissance toward Kherson and met no organized resistance before withdrawing. After they returned to Kinburn, the French and British commanders determined that the fort could be rebuilt and held through the upcoming winter. A force of 1,700 men was left behind to garrison the position, along with the three ironclad batteries. The rest of the force returned to the Crimea. Though the British had initially considered continuing up the Dnieper to capture Nikolaev, it became clear after the seizure of Kinburn that to do so would require much larger numbers of soldiers to clear the cliffs that dominated the river than had been originally estimated. The British planned to eventually launch an offensive to take Nikolaev in 1856, but the war ended before it could be begun.

Since they lacked the forces to take Nikolaev in a single campaign, the seizure of Kinburn proved to have limited strategic effect. Nevertheless, the attack on Kinburn was significant in that it demonstrated that the French and British fleets had developed effective amphibious capabilities and had technological advantages that gave them a decisive edge over their Russian opponents. The destruction of Kinburn's coastal fortifications completed the Anglo-French naval campaign in the Black Sea; the Russians no longer had any meaningful forces left to oppose them at sea. The British and French navies planned to transfer forces to the

On 20 October, Bazaine's infantry conducted reconnaissance toward Kherson and met no organized resistance before withdrawing. After they returned to Kinburn, the French and British commanders determined that the fort could be rebuilt and held through the upcoming winter. A force of 1,700 men was left behind to garrison the position, along with the three ironclad batteries. The rest of the force returned to the Crimea. Though the British had initially considered continuing up the Dnieper to capture Nikolaev, it became clear after the seizure of Kinburn that to do so would require much larger numbers of soldiers to clear the cliffs that dominated the river than had been originally estimated. The British planned to eventually launch an offensive to take Nikolaev in 1856, but the war ended before it could be begun.

Since they lacked the forces to take Nikolaev in a single campaign, the seizure of Kinburn proved to have limited strategic effect. Nevertheless, the attack on Kinburn was significant in that it demonstrated that the French and British fleets had developed effective amphibious capabilities and had technological advantages that gave them a decisive edge over their Russian opponents. The destruction of Kinburn's coastal fortifications completed the Anglo-French naval campaign in the Black Sea; the Russians no longer had any meaningful forces left to oppose them at sea. The British and French navies planned to transfer forces to the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, took place on the tip of the Kinburn Peninsula (on the south shore of the Dnieper–Bug estuary

The Dnieper–Bug estuary ( uk, Дніпровсько-Бузький лиман) is an open estuary, or liman, of two rivers: the Dnieper and the Southern Bug (also called the Boh River). It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea and i ...

in what is now Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

) on 17 October 1855. During the battle a combined fleet of vessels from the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

and the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

bombarded Russian coastal fortifications after an Anglo-French ground force had besieged them. Three French ironclad batteries carried out the main attack, which saw the main Russian fortress destroyed in an action that lasted about three hours.

The battle, although strategically insignificant with little effect on the outcome of the war, is notable for the first use of modern ironclad warship

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

s in action. Although frequently hit, the French ships destroyed the Russian forts within three hours, suffering minimal casualties in the process. This battle convinced contemporary navies to design and build new major warships with armour plating

Military vehicles are commonly armoured (or armored; see spelling differences) to withstand the impact of shrapnel, bullets, shells, rockets, and missiles, protecting the personnel inside from enemy fire. Such vehicles include armoured fightin ...

; this instigated a naval arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

between France and Britain lasting over a decade.

Background

In September 1854, the Anglo-French army that had been at Varna was ferried across theBlack Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

and landed on the Crimean Peninsula

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. They then fought their way to the main Russian naval base on the peninsula, the city of Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, which they placed under siege. The Russian garrison eventually withdrew from the city in early September 1855, freeing the French and British fleets for other tasks. A discussion ensued over what target should be attacked next; the French and British high commands considered driving from the Crimea to Kherson

Kherson (, ) is a port city of Ukraine that serves as the administrative centre of Kherson Oblast. Located on the Black Sea and on the Dnieper River, Kherson is the home of a major ship-building industry and is a regional economic centre. I ...

and launching major campaigns in Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

or the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

. Instead, at the urging of French commanders, they settled on a smaller-scale operation to seize the Russian fort at Kinburn, which protected the mouth of the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

. The British argued that to seize Kinburn without advancing to Nikolaev would only serve to warn the Russians of the threat to the port. Fox Maule-Ramsay, then the British Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, suggested that without a plan to exploit the capture of the fortress, the only purpose of the operation would be to give the fleets something to do.

Forces involved

The fortress was located on the Kinburn Spit, at the extreme western end of the Kinburn Peninsula, and consisted of three separate fortifications. The primary fort, built of stone, square, and equipped with

The fortress was located on the Kinburn Spit, at the extreme western end of the Kinburn Peninsula, and consisted of three separate fortifications. The primary fort, built of stone, square, and equipped with bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

s, held 50 guns, some of which were mounted in protective casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s; the rest were in ''en barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

'' mountings, firing over the parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). ...

s. Two smaller fortresses were located further down the spit, mounting ten and eleven guns, respectively. The first was a small stone fort, while the second was a simple sand earthwork. The forts were armed only with medium and smaller calibre guns, the largest guns being 24-pounders. Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Maxim Kokhanovitch commanded the garrison of 1,500 men, most of whom were stationed in the main fort. Across the estuary was Fort Nikolaev in the town of Ochakov with fifteen more guns, but these were too far away to play a role in the battle.Wilson, p. XXXIV

To attack the forts, the British and French assembled a fleet centred on four French and six British ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

, led by British Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Edmund Lyons and the French Vice Admiral Armand Joseph Bruat

Armand Joseph Bruat (Colmar, 26 May 1796 – '' Montebello'', off Toulon, 19 November 1855) was a French admiral.

Biography

Bruat joined the French Navy in 1811, at the height of the Napoleonic Wars. His early career included far-ranging sea ...

. The British contributed a further seventeen frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

s and sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

, ten gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

s, and six bomb vessel

A bomb vessel, bomb ship, bomb ketch, or simply bomb was a type of wooden sailing naval ship. Its primary armament was not cannons (long guns or carronades) – although bomb vessels carried a few cannons for self-defence – but mortars mounted ...

s, along with ten transport vessels. The French squadron included three corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

s, four aviso

An ''aviso'' was originally a kind of dispatch boat or "advice boat", carrying orders before the development of effective remote communication.

The term, derived from the Portuguese and Spanish word for "advice", "notice" or "warning", an ...

s, twelve gunboats, and five bomb vessels. The transports carried a force of 8,000 men from French and British Army regiments that would be used to besiege the forts.

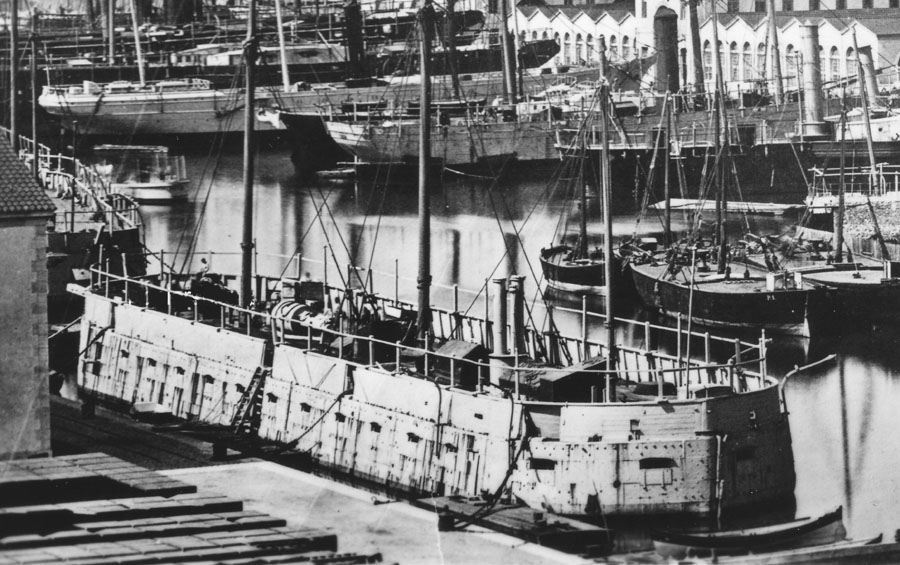

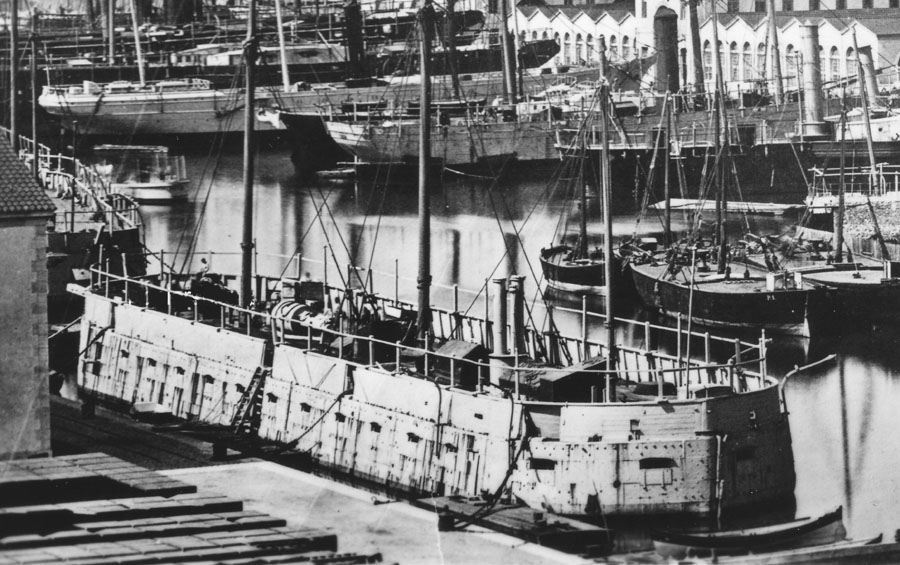

In addition to the contingent of conventional sailing warships, the French squadron brought three experimental ironclad warships that had recently arrived from France. These, the first three ironclad batteries of the —, , and —had been sent to the Black Sea in late July, but they arrived too late to take part in the siege of Sevastopol.Greene & Massignani, p. 27 These vessels, the first ironclad warships, carried eighteen 50-pounder guns and were protected with of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

armour. Observers speculated that these untested warships would be ineffective in combat, owing to their slow speed and poor handling.

Battle

In an effort to confuse the Russians, the combined fleet made a feint westward toward

In an effort to confuse the Russians, the combined fleet made a feint westward toward Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

on 8 October before turning east to Kinburn. The combined French and British fleet arrived off Kinburn on 14 October. That night, a force of nine gunboats escorted transports carrying 8,000 men, led by François Achille Bazaine

François Achille Bazaine (13 February 181123 September 1888) was an officer of the French army. Rising from the ranks, during four decades of distinguished service (including 35 years on campaign) under Louis-Philippe and then Napoleon III, he ...

, who were landed behind the forts, further up the peninsula. The gunboat force was commanded by Rear Admiral Houston Stewart, who ordered his crews to hold their fire in the darkness unless they were able to clearly see a Russian target. The Russians did not launch a counterattack on the landing, allowing the French and British soldiers to dig trench positions while the gunboats shelled the main fort, albeit ineffectively. By the morning of the 17th, the soldiers had completed significant entrenchments, with French troops facing the fortifications and British troops manning the outward defences against a possible Russian attempt to relieve the garrison. By this time, the French had begun building sapping

Sapping is a term used in siege operations to describe the digging of a covered trench (a "sap") to approach a besieged place without danger from the enemy's fire. (verb) The purpose of the sap is usually to advance a besieging army's positio ...

trenches, which then came under fire from the Russian fortress. In the meantime, on the night of the 16th, a French vessel had taken depth sounding

Depth sounding, often simply called sounding, is measuring the depth of a body of water. Data taken from soundings are used in bathymetry to make maps of the floor of a body of water, such as the seabed topography.

Soundings were traditional ...

s close to the main fort to determine how closely the ships could approach it. Throughout this time, heavy seas prevented the fleet from launching a sustained bombardment of the Russian positions.

At around 9:00 on 17 October, the Anglo-French fleet moved into position to begin their bombardment.Grant, p. 120 The ships of the line had a difficult time getting into effective positions owing to the shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s in the surrounding water, and so much of the work fell to smaller and shallower draught vessels, most prominently the three ironclad batteries. The floating batteries were anchored just from the Russian fortress, where they proved to be immune to Russian artillery fire, which either bounced off or exploded harmlessly on their wrought iron armour plating. The French and British ships of the line were anchored further out, at around , while the bomb vessels were placed further still, at . While their guns battered at the fortifications, the ironclads each had a contingent of Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious warfare, amphibious light infantry and also one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighti ...

who inflicted significant casualties on the Russian gun crews. The only significant hit on the ironclad batteries was one shell that entered a gunport on ''Dévastation'', which killed two men but otherwise caused no serious damage to the ship.Wilson, p. XXXV

The cannonade started fires in the main fortress and rapidly disabled Russian guns. Once Russian fire started to decrease, the gunboats moved into position behind the fortresses and began to bombard them as well. In the course of the morning, the three French vessels fired some 3,000 shells into the fort, and by 12:00, it had been neutralized by the combined firepower of the Anglo-French fleet.Sondhaus, p. 61 A single Russian hoisted a white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symbolize ...

above the fort to indicate their surrender, and Kokhanovitch walked out to speak with the French ground commander. According to historian James Grant, around 1,100 Russians of the 1,500-man garrison survived the battle and were allowed to leave without their weapons. Herbert Wilson puts the Russian casualties much lower, at 45 dead and 130 wounded. For the French and British, the only men killed were the two aboard ''Dévastation'', with a further 25 wounded, all of whom were aboard the floating batteries. In the course of the battle, ''Dévastation'' was hit 75 times, while ''Lave'' received 66 hits and ''Tonnante'' was hit around the same number of times. None of the ships emerged from the battle with more than minor dents in their armour plate.Wilson, p. XXXVI

Aftermath

On 20 October, Bazaine's infantry conducted reconnaissance toward Kherson and met no organized resistance before withdrawing. After they returned to Kinburn, the French and British commanders determined that the fort could be rebuilt and held through the upcoming winter. A force of 1,700 men was left behind to garrison the position, along with the three ironclad batteries. The rest of the force returned to the Crimea. Though the British had initially considered continuing up the Dnieper to capture Nikolaev, it became clear after the seizure of Kinburn that to do so would require much larger numbers of soldiers to clear the cliffs that dominated the river than had been originally estimated. The British planned to eventually launch an offensive to take Nikolaev in 1856, but the war ended before it could be begun.

Since they lacked the forces to take Nikolaev in a single campaign, the seizure of Kinburn proved to have limited strategic effect. Nevertheless, the attack on Kinburn was significant in that it demonstrated that the French and British fleets had developed effective amphibious capabilities and had technological advantages that gave them a decisive edge over their Russian opponents. The destruction of Kinburn's coastal fortifications completed the Anglo-French naval campaign in the Black Sea; the Russians no longer had any meaningful forces left to oppose them at sea. The British and French navies planned to transfer forces to the

On 20 October, Bazaine's infantry conducted reconnaissance toward Kherson and met no organized resistance before withdrawing. After they returned to Kinburn, the French and British commanders determined that the fort could be rebuilt and held through the upcoming winter. A force of 1,700 men was left behind to garrison the position, along with the three ironclad batteries. The rest of the force returned to the Crimea. Though the British had initially considered continuing up the Dnieper to capture Nikolaev, it became clear after the seizure of Kinburn that to do so would require much larger numbers of soldiers to clear the cliffs that dominated the river than had been originally estimated. The British planned to eventually launch an offensive to take Nikolaev in 1856, but the war ended before it could be begun.

Since they lacked the forces to take Nikolaev in a single campaign, the seizure of Kinburn proved to have limited strategic effect. Nevertheless, the attack on Kinburn was significant in that it demonstrated that the French and British fleets had developed effective amphibious capabilities and had technological advantages that gave them a decisive edge over their Russian opponents. The destruction of Kinburn's coastal fortifications completed the Anglo-French naval campaign in the Black Sea; the Russians no longer had any meaningful forces left to oppose them at sea. The British and French navies planned to transfer forces to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

the following year to strengthen operations there. Diplomatic pressure from still-neutral Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

convinced Czar Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Fin ...

to sue for peace, which was concluded the following February with the Treaty of Paris.

In his report, Bruat informed his superiors that " erything may be expected from these formidable engines of war." The effectiveness of the ironclad batteries in neutralizing the Russian guns, though still debated by naval historians, nevertheless convinced French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

to order more ironclad warships. Their success at Kinburn, coupled with the devastating effect new shell-firing guns had had on wooden warships at the Battle of Sinop earlier in the war led most French naval officers to support the new armoured vessels. Napoleon III's programme produced the first sea-going ironclad, , initiating a naval construction race between France and Britain that would last until the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. The British Royal Navy, which had five ironclad batteries under construction, laid down another four after the victory at Kinburn, and replied to ''Gloire'' with a pair of armoured frigates of their own, and . France built a further eleven batteries built to three different designs, and the Russian Navy built fifteen armoured rafts for harbour defence.Greene & Massignani, pp. 31–35

See also

*Battle of Kinburn (1787)

The Battle of Kinburn was fought on 12 October ( N.S.)/1 October ( O.S.) 1787 as part of the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792).

A weak fortress, Kinburn was located opposite Ochakov on a sand bank forming a part of the Dnieper river delta. It ...

Notes

References

* * * * * {{good article Kinburn 1855 Kinburn (1855) Kinburn (1855) Kinburn (1855) Kinburn (1855) 1855 in France Kinburn 1855 October 1855 events