Battle of Granicus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of the Granicus in May 334 BC was the first of three major battles fought between

There are three different accounts of the battle given by the ancient historians Arrian, Plutarch and Diodorus Siculus. Arrian's account is the longest and most detailed, Plutarch's account is shorter but corresponds with Arrian's narrative except for some small differences. The account of Diodorus Siculus however is fundamentally different from that of Arrian and Plutarch.

There are three different accounts of the battle given by the ancient historians Arrian, Plutarch and Diodorus Siculus. Arrian's account is the longest and most detailed, Plutarch's account is shorter but corresponds with Arrian's narrative except for some small differences. The account of Diodorus Siculus however is fundamentally different from that of Arrian and Plutarch.

Continuing Arrian's narrative, Alexander and his men engaged the Persians and their leaders in a hard-fought battle. The Macedonians eventually got the upper hand because their lance (the

Continuing Arrian's narrative, Alexander and his men engaged the Persians and their leaders in a hard-fought battle. The Macedonians eventually got the upper hand because their lance (the

Plutarch's account focuses more on the ''

Plutarch's account focuses more on the ''

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

of Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an Classical antiquity, ancient monarchy, kingdom on the periphery of Archaic Greece, Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. Th ...

and the Persian Achaemenid Empire. The battle took place on the road from Abydus to Dascylium

Dascylium, Dascyleium, or Daskyleion ( grc, Δασκύλιον, Δασκυλεῖον), also known as Dascylus, was a town in Anatolia some inland from the coast of the Propontis, at modern Ergili, Turkey. Its site was rediscovered in 1952 and ...

, at the crossing of the Granicus in the Troad

The Troad ( or ; el, Τρωάδα, ''Troáda'') or Troas (; grc, Τρῳάς, ''Trōiás'' or , ''Trōïás'') is a historical region in northwestern Anatolia. It corresponds with the Biga Peninsula ( Turkish: ''Biga Yarımadası'') in the � ...

region, which is now called the Biga River

Biga may refer to:

Places

* Biga, Çanakkale, a town and district of Çanakkale Province in Turkey

* Sanjak of Biga, an Ottoman province

* Biga Çayı, a river in Çanakkale Province

* Biga Peninsula, a peninsula in Turkey, in the northwest part ...

in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

. In the battle Alexander defeated the field army of the Persian satraps of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, which defended the river crossing. After this battle, the Persians were forced on the defensive in the cities that remained under their control in the region.

Background

After winning the Battle of Chaeronea in 337 BC, kingPhilip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

forced most of the Greek states into a military alliance, the Hellenic League. Its goal was to make war on the Persian Achaemenid Empire to avenge the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC. He managed to convince the other Greek states to elect him as the leader of the League and started preparing for the war.

At the same time the Achaemenid Empire had been in crisis since the murder of its king Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

in 338 BC. An important consequence of this was that Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

again seceded from the empire. At this time there was no large Persian army in Asia Minor and the Persian fleet was not expected in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

soon. Philip most likely wanted to exploit the chaos in the empire, but could not launch a large-scale invasion of Asia Minor because his entire army was not yet ready. For this reason he probably sent a smaller part of his army which could be deployed. In the spring of 336 BC he ordered a Macedonian expeditionary corps of several thousand soldiers to land on the western coast of Asia Minor. The likely mission of this advance-guard was to conquer as much territory as possible, or at the very least establish a bridgehead on the Asian side of the Hellespont to facilitate the crossing of the main army later.

The advance guard was most likely led by Parmenion

Parmenion (also Parmenio; grc-gre, Παρμενίων; c. 400 – 330 BC), son of Philotas, was a Macedonian general in the service of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. A nobleman, Parmenion rose to become Philip's chief milita ...

, Philip's best general, with Attalus as second in command. Initially the campaign was a success, with many of the Greek cities of western Asia Minor surrendering peacefully to the Macedonians. At the end of 336 BC this all changed. Philip was murdered, most likely in October 336 BC. Philip was succeeded by his son, Alexander III, who had to put down several revolts in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and Greece first to reassert Macedonian authority. This distracted him from the operations in Asia Minor. Meanwhile, Darius III had become the new Great King of the Achaemenid Empire, around the autumn of 336 BC. He managed to stabilize the empire and started a counter-offensive against the Macedonian expeditionary force.

Darius prioritized the suppression of the Egyptian revolt, which probably took place from the end of 336 BC to February 335 BC. When this was done he sent Memnon of Rhodes

Memnon of Rhodes (Greek: Μέμνων ὁ Ῥόδιος; c. 380 – 333 BC) was a prominent Rhodian Greek commander in the service of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Related to the Persian aristocracy by the marriage of his sister to the satr ...

to Asia Minor at the head of a force of Greek mercenaries, who were infantry fighting as hoplites. Memnon defeated a Macedonian force at either Magnesia ad Sipylum

Magnesia Sipylum ( el, Mαγνησία ἡ πρὸς Σιπύλῳ or ; modern Manisa, Turkey) was a city of Lydia, situated about 65 km northeast of Smyrna (now İzmir) on the river Hermus (now Gediz) at the foot of Mount Sipylus. The ci ...

or Magnesia on the Maeander

Magnesia or Magnesia on the Maeander ( grc, Μαγνησία ἡ πρὸς Μαιάνδρῳ or ; la, Magnesia ad Maeandrum) was an ancient Greek city in Ionia, considerable in size, at an important location commercially and strategically in th ...

, probably in early spring 335 BC. Later that year another Macedonian force was defeated by a Persian army in the Troad

The Troad ( or ; el, Τρωάδα, ''Troáda'') or Troas (; grc, Τρῳάς, ''Trōiás'' or , ''Trōïás'') is a historical region in northwestern Anatolia. It corresponds with the Biga Peninsula ( Turkish: ''Biga Yarımadası'') in the � ...

, possibly under the command of one or more Persian satraps. By the end of 335 BC most of the Greek cities had been restored to Persian control and the expeditionary force retained only Abydus and perhaps Rhoeteum.

Prelude

Once Alexander had defeated the rebellions in the Balkans and Greece, he marched his army to the Hellespont in early spring 334 BC. His army numbered c. 32,000 infantry and c. 5,000 cavalry. He arrived atSestus

Sestos ( el, Σηστός, la, Sestus) was an ancient city in Thrace. It was located at the Thracian Chersonese peninsula on the European coast of the Hellespont, opposite the ancient city of Abydos, and near the town of Eceabat in Turkey.

In ...

twenty days later, where he split his army for the crossing of the Hellespont. The main part of the army was transported from Sestus to Abydus in Asia Minor, while Alexander crossed with the remainder of the infantry from Elaeus

Elaeus ( grc, Ἐλαιοῦς ''Elaious'', later ''Elaeus''), the “Olive City”, was an ancient Greek city located in Thrace, on the Thracian Chersonese. Elaeus was located at the southern end of the Hellespont (now the Dardanelles) near th ...

, landing near Cape Sigeum

Sigeion (Ancient Greek: , ''Sigeion''; Latin: ''Sigeum'') was an ancient Greek city in the north-west of the Troad region of Anatolia located at the mouth of the Scamander (the modern Karamenderes River). Sigeion commanded a ridge between the Aeg ...

. After visiting Ilium, he passed Arisba, Percote

Percote or Perkote ( grc, Περκώτη) was a town or city of ancient Mysia on the southern (Asian) side of the Hellespont, to the northeast of Troy. Percote is mentioned a few times in Greek mythology, where it plays a very minor role each time. ...

, Lampsacus

Lampsacus (; grc, Λάμψακος, translit=Lampsakos) was an ancient Greek city strategically located on the eastern side of the Hellespont in the northern Troad. An inhabitant of Lampsacus was called a Lampsacene. The name has been transmitte ...

, Colonae

Kolonai ( grc, αἱ Κολωναί, hai Kolōnai; la, Colonae) was an ancient Greek city in the south-west of the Troad region of Anatolia. It has been located on a hill by the coast known as Beşiktepe ('cradle hill'), about equidistant betwe ...

and Hermotus.

Darius would have been informed about Alexander's movements for some time, maybe as early as the invasion force had left Macedon. This did not alarm the Great King yet, who left the defense of Asia Minor to his satraps there. The reasons for this may have been that Alexander had not proven himself as a commander abroad yet and that the Macedonian expeditionary force had been pushed back without much difficulty the previous year.

The Persian satraps and commanders were encamped near Zeleia

Zeleia ( grc, Ζέλεια) was a town of the ancient Troad, at the foot of Mount Ida and on the banks of the river Aesepus (both located in Turkey), at a distance of 80 stadia from its mouth. It is mentioned by Homer in the Trojan Battle Order ...

with their army when they were informed of Alexander's crossing. The army was led by Arsites

Arsites ( peo, *R̥šitaʰ; grc, Ἀρσίτης ; fa, آرستیس) was Persian satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia in the Achaemenid Empire in the 4th century BC. His satrapy also included the region of Paphlagonia.

In 340 BC, he sent a merce ...

, the satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia

Hellespontine Phrygia ( grc, Ἑλλησποντιακὴ Φρυγία, Hellēspontiakē Phrygia) or Lesser Phrygia ( grc, μικρᾶ Φρυγία, mikra Phrygia) was a Persian satrapy (province) in northwestern Anatolia, directly southeast of ...

, Spithridates

Spithridates ( Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; fl. 365–334 BC) was a Persian satrap of Lydia and Ionia under the high king Darius III Codomannus. He was one of the Persian commanders at the Battle of the Granicus, in 334 BC. In this engagem ...

, satrap of Lydia and Ionia, Arsames

Arsames ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠𐎶 Aršāma, modern Persian:،آرسام، آرشام Arshām, Greek: ) was the son of Ariaramnes and the grandfather of Darius I. He was traditionally claimed to have briefly been king of Persia during the ...

, satrap of Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

, Rheomithres Rheomithres (Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ) was a Persian people, Persian noble. He was father of several children, including Phrasaortes whom Alexander the Great appointed satrap of Persis in 330 BC. He joined in the Great Satraps' Revolt of the ...

, Petenes, Niphates

Niphates is a mountain chain in Armenia that John Milton uses in ''Paradise Lost'' iii. 742 as Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as the Devil, and sometimes also called Luci ...

and Memnon of Rhodes. While the ancient historians don't explicitly identify a commander-in-chief for the Persians, modern historians consider Arsites to have been in overall command because the enemy had invaded his territory.

A council was held by the Persians at Zeleia to discuss the state of affairs. The ancient historians Arrian and Diodorus Siculus claim that Memnon advised the Persians to avoid open battle with the Macedonians. He reasoned that the Macedonian infantry was superior to theirs and that Alexander was present in person, while Darius was not with them. He recommended a scorched earth strategy so that Alexander would not be able to continue his campaign due to lack of supplies. Arsites and the other Persians rejected Memnon's advice because they wanted to protect the property of their subjects. They also suspected Memnon of trying to prolong the war so that he could gain favor with Darius.

W. J. McCoy compares Memnon's advice with the wise counsel given by Greeks to Persians in the work of Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

. In Herodotus, the rejection of such counsel led to misfortune for the Persians and was employed to ridicule them. For this reason he suggests that Memnon's advice was an invention by Arrian and Diodorus. Pierre Briant

Pierre Briant (born 30 September 1940 in Angers) is a French Iranologist, Professor of History and Civilisation of the Achaemenid World and the Empire of Alexander the Great at the Collège de France (1999 onwards), Doctor Honoris Causa at the Uni ...

argues that even if the debate took place as described, the relevance of Memnon's counsel was overstated because discussing strategy was not the purpose of the meeting. Most likely Darius had already ordered his satraps to engage Alexander's army in battle, so the council at Zeleia was held to discuss the tactics of the upcoming battle rather than the strategy of the war. After the council, the Persian army took up position at the eastern bank of the Granicus River and waited for Alexander's attack.

According to Arrian, Alexander heard of the location of the Persians from his scouts while he was moving towards the Granicus. He had his army arranged in battle formation. Parmenion was worried that the army could not cross the river with its front extended, and would have to cross over in column with its battle formation disrupted. Because this would make the army vulnerable to Persian attack, he advised Alexander that the army should encamp on the western bank and make an uncontested crossing tomorrow at dawn. Alexander did not want to wait and ordered an immediate attack.

These discussions on strategy and tactics between Parmenion and Alexander are a recurring motif in the writings of ancient historians. In these exchanges Parmenion is depicted as careful, while Alexander is willing to take more risks. Alexander always rejects the advice of Parmenion and is then successful in realizing his own bold plan, which the old general advised him against. This motif may have originated in the work of Callisthenes

Callisthenes of Olynthus (; grc-gre, Καλλισθένης; 360327 BCE) was a well-connected Greek historian in Macedon, who accompanied Alexander the Great during his Asiatic expedition. The philosopher Aristotle was Callisthenes's great ...

for the purpose of enhancing the heroism of Alexander. As a consequence, historians have suggested that the discussion may have been fictional.

The battle was fought in the Macedonian month of Daisios, May in the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

. Before the battle, some of the Macedonian officers voiced their reluctance to fight because religious custom required them to avoid battles during this month. Alexander solved this by declaring that the current month should be considered a second Artemision. This month preceded Daisios and did not carry a taboo on warfare.

Location

The Granicus is today called theBiga River

Biga may refer to:

Places

* Biga, Çanakkale, a town and district of Çanakkale Province in Turkey

* Sanjak of Biga, an Ottoman province

* Biga Çayı, a river in Çanakkale Province

* Biga Peninsula, a peninsula in Turkey, in the northwest part ...

( tr, Biga Çayı). Traditionally the ford where the battle took place has been located above the confluence of the river which runs through Gümüşçay and the Biga River, or further downstream on the Biga River. More recently N. G. L. Hammond proposed that at the time of the battle the Biga River possibly flowed further east in its valley. In modern times, evidence of an old riverbed can still be seen there. Furthermore, the ancient historians describe a long continuous ridge where the Greek mercenary infantry of the Persians was posted. Because there is only one candidate for this ridge, Hammond has placed the ford between the modern villages Gümüşçay (formerly called Dimetoka) and Çeşmealtı. This theory found support in later scholarship on the battle. The modern observations that the river is not difficult to cross contradicts the ancient historians, who emphasized the hardship of the fording of the river. The ancient historians might have exaggerated to make Alexander's accomplishment seem more formidable.

Opposing forces

Macedonian army

The Macedonian army consisted mostly of infantry. The heavy infantry numbered 12,000 and included the Foot Companions and a smaller group of elitehypaspists

A hypaspist ( el, Ὑπασπιστής "shield bearer" or "shield covered") is a squire, man at arms, or "shield carrier". In Homer, Deiphobos advances "" () or under cover of his shield. By the time of Herodotus (426 BC), the word had come ...

. The light infantry totalled 1,000 and contained archers

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In mo ...

and elite Agrianian

The Agrianes (Ancient Greek: Ἀγρίανες, ''Agrianes'' or Ἀγρίαι ''Agriai'') or Agrianians, were a tribe whose country was centered at Upper Strymon, in present-day central Western Bulgaria as well as southeasternmost Serbia, at the ...

javelin-men. The heavy cavalry was made up of 1,800 elite Companion cavalry

The Companions ( el, , ''hetairoi'') were the elite cavalry of the Macedonian army from the time of king Philip II of Macedon, achieving their greatest prestige under Alexander the Great, and regarded as the first or among the first shock cav ...

, 1,800 Thessalian cavalry and 600 Greek allied cavalry. The light cavalry numbered 900 in total and was composed of ''prodromoi

In ancient Greece, the ''prodromoi'' (singular: ''prodromos'') were skirmisher light cavalry. Their name (ancient Greek: ''πρόδρομοι'', ''prοdromoi'', lit. "pre-cursors," "runners-before," or "runners-ahead") implies that these cavalry ' ...

'', Paeonians

Paeonians were an ancient Indo-European people that dwelt in Paeonia. Paeonia was an old country whose location was to the north of Ancient Macedonia, to the south of Dardania, to the west of Thrace and to the east of Illyria, most of their lan ...

and Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

. Alexander also possessed Greek allied and mercenary infantry, but he had marched to the Granicus without them. In total, Alexander's army numbered 12,000 heavy infantry, 1,000 light infantry and 5,100 cavalry for a total of 18,100 men.

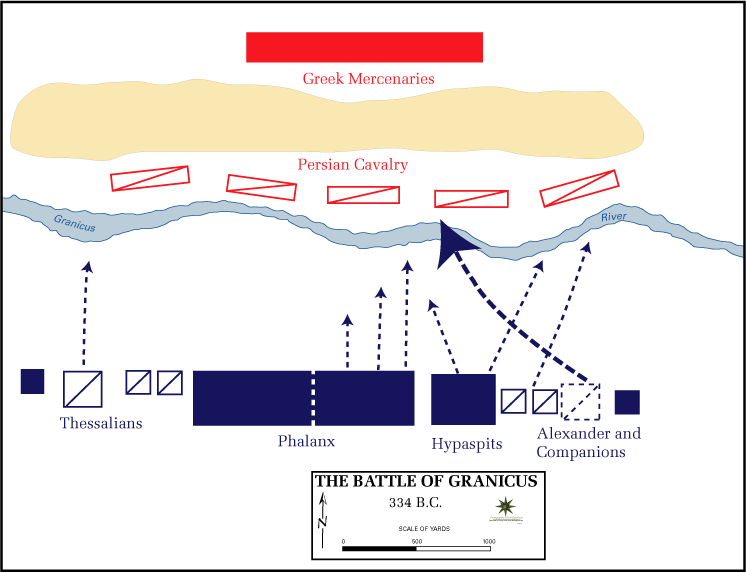

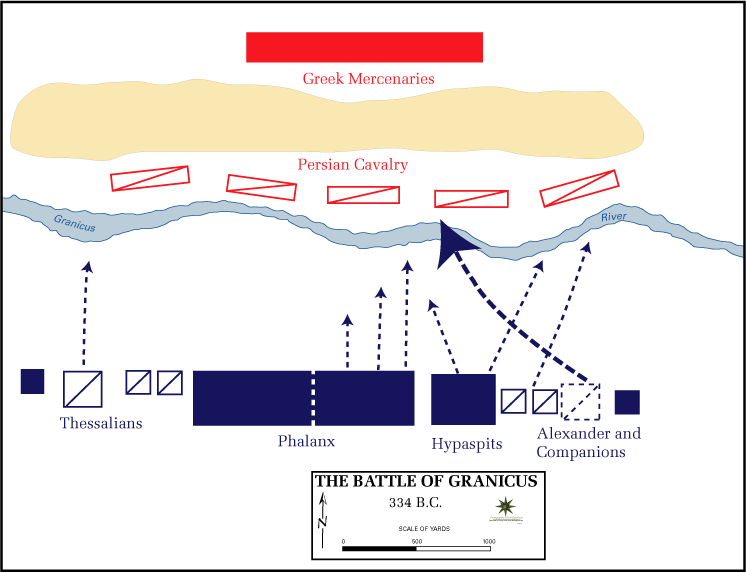

From the right wing to the left, Alexander placed seven of his eight squadrons of Companion cavalry, along with the archers and Agrianians, under the command of Philotas

Philotas ( el, Φιλώτας; 365 BC – October 330 BC) was the eldest son of Parmenion, one of Alexander the Great's most experienced and talented generals. He rose to command the Companion Cavalry, but was accused of conspiring against Alex ...

. Because the Agrianians usually fought interspersed with the Companion cavalry, they were most likely placed in front of them. The ''prodromoi'', the Paeonian cavalry and the eighth squadron of the Companion cavalry under Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

were posted next to them. Overall command of these three cavalry units was held by Amyntas, son of Arrhabaeus. After them came the hypaspists commanded by Nicanor, which guarded the right flank of the Foot Companions next to them. There were six units of Foot Companions: led by Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to beco ...

, Coenus, Craterus

Craterus or Krateros ( el, Κρατερός; c. 370 BC – 321 BC) was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi. Throughout his life he was a loyal royalist and supporter of Alexander the Great.Anson, Edward M. (20 ...

, Amyntas the son of Andromenes, Philip the son of Amyntas, and Meleager

In Greek mythology, Meleager (, grc-gre, Μελέαγρος, Meléagros) was a hero venerated in his ''temenos'' at Calydon in Aetolia. He was already famed as the host of the Calydonian boar hunt in the epic tradition that was reworked by Ho ...

. To the left of Meleager's Foot Companions were the Thracian cavalry under the command of Agathon

Agathon (; grc, Ἀγάθων; ) was an Athenian tragic poet whose works have been lost. He is best known for his appearance in Plato's ''Symposium,'' which describes the banquet given to celebrate his obtaining a prize for his first tragedy a ...

. Next to them were stationed the allied Greek cavalry under Philip, son of Menelaus. At the extreme left were the Thessalian cavalry under the command of Calas. Alexander placed Parmenion in overall command of the Foot Companions of Philip and Meleager, and the cavalry on the left wing. Alexander commanded the remainder of the army on the right wing. The Greek allied and mercenary infantry, which were part of the invasion force, were not used during the battle.

Persian army

For the Persian army Arrian gives a number of almost 20,000 infantry, all Greek mercenaries, and 20,000 cavalry. Diodorus gives a figure of 10,000 cavalry and 100,000 infantry. Justin gives an even higher number of 600,000 men in total for the Persians. The historian Azar Gat explains that although the Persian Empire and its armies were large, the size of its armies were wildly exaggerated in the Greek sources. Gat adds that this was an "invariable" habit of pre-modern writers, as they both lacked precise information and were patriotically biased. N. G. L. Hammond accepts the Persian troop numbers given by Arrian. A. M. Devine and Krzysztof Nawotka regard the numbers given by Justin and the number for infantry given by Diodorus to be fantastical because such a large army would have been a logistical impossibility. Both historians consider the figure of 10,000 cavalry given by Diodorus to be more plausible. J. F. C. Fuller also considers a number of 10,000 cavalry to be more likely, but he doesn't mention the figure of Diodorus. Arrian's claim on the strength and composition of the Persian infantry has elicited more detailed discussion. There have been arguments that the figure of 20,000 is accurate, but also included non-Greek native infantry. Others have argued that Greek mercenaries may have been the only infantry present but were not as numerous. Krzysztof Nawotka considers Arrian's claim of 20,000 infantry credible, but does not think it consisted entirely of Greek mercenaries. Such a large force of mercenaries would have been raised only very occasionally, after a long period of preparation and under the command of the Great King. Because the Achaemenids had not made such preparations for the battle, he judges that only a small fraction of the infantry were Greek mercenaries. Accordingly, local detachments of little military value made up the vast majority of the infantry. Based on Plutarch's statement that the infantry of both sides engaged after the Macedonian phalanx crossed the river,Ernst Badian

Ernst Badian (8 August 1925 – 1 February 2011) was an Austrian-born classical scholar who served as a professor at Harvard University from 1971 to 1998.

Early life and education

Badian was born in Vienna in 1925 and in 1938 fled the Nazis wit ...

likewise believes that non-Greek infantry was part of the Persian army and posted directly behind the cavalry. In this light, he considers 20,000 as an reasonable estimate for the total number of infantry. He believes that Arrian's claim that all Persian infantry consisted of Greek mercenaries was either a mistake or an attempt to enhance Alexander's glory.

A.M. Devine argues that Arrian likely exaggerated the number of Greek mercenaries for propaganda purposes. He notes that the only other information on Greek mercenaries in Asia Minor at that time is given by Diodorus and Polyaenus

Polyaenus or Polyenus ( ; see ae (æ) vs. e; grc-gre, Πoλύαινoς, Polyainos, "much-praised") was a 2nd-century CE Greek author, known best for his ''Stratagems in War'' ( grc-gre, Στρατηγήματα, Strategemata), which has been pr ...

. Diodorus writes that Memnon's force of Greek mercenaries, which Darius III had sent to Asia Minor to fight the Macedonian expeditionary force, numbered 5,000 men. Polyaenus

Polyaenus or Polyenus ( ; see ae (æ) vs. e; grc-gre, Πoλύαινoς, Polyainos, "much-praised") was a 2nd-century CE Greek author, known best for his ''Stratagems in War'' ( grc-gre, Στρατηγήματα, Strategemata), which has been pr ...

gives a lower number for these, 4,000. Assuming that Arrian was right in his claim that the infantry consisted exclusively of Greek mercenaries and that the figure of 10,000 cavalry given by Diodorus is plausible, he suggests that the Persian army likely numbered 14,000 to 15,000 men. This was significantly inferior both in numbers and quality compared to the 18,100 men fielded by Alexander. Like A. M. Devine, J. F. C. Fuller thinks the number of 5,000 mercenaries given by Diodorus is more realistic, but he thinks there must have also been a considerable force of local levies.

A.M. Devine goes on to argue that this inferiority of the Persian force would explain why the Persians chose to defend a rivier crossing and place their cavalry in the front line. It would also explain why Alexander decided to risk a frontal attack there. Likewise, the encirclement and massacre of the Greek mercenaries later during the battle would have been unlikely if they had actually numbered 20,000 instead of 4,000 or 5,000. Finally, the low estimate for the size of the Persian army would fit with the small number of casualties for the Macedonians.

The Persians stationed their cavalry along the bank of the Granicus. The left wing was held by Memnon and Arsames, each with their own cavalry units. Next to them Arsites commanded the Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

n horsemen. Spithridates was placed next to him and led the Hyrcania

Hyrcania () ( el, ''Hyrkania'', Old Persian: 𐎺𐎼𐎣𐎠𐎴 ''Varkâna'',Lendering (1996) Middle Persian: 𐭢𐭥𐭫𐭢𐭠𐭭 ''Gurgān'', Akkadian: ''Urqananu'') is a historical region composed of the land south-east of the Caspian ...

n cavalry. The center was held by cavalry of unspecified ethnicity. The right wing consisted of 1,000 Median cavalry, 2,000 cavalry headed by Rheomithres and another unit of 2,000 Bactrian horse. The Persians moved some of their cavalry to reinforce their left wing when they noticed Alexander himself was stationed opposite this wing. The Greek mercenaries were placed behind the cavalry and led by the Persian Omares.

Historians have criticized several decisions made by the Persian commanders. One of these is the deployment of the cavalry on the river's bank, because it did not allow the cavalry to charge

Charge or charged may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* '' Charge, Zero Emissions/Maximum Speed'', a 2011 documentary

Music

* ''Charge'' (David Ford album)

* ''Charge'' (Machel Montano album)

* ''Charge!!'', an album by The Aqu ...

. This has been explained by the fact that the Persian cavalry at that time did not use charge tactics yet. Instead, they would approach enemy formations and attack them with javelins to disrupt them from a distance. Once the formation was sufficiently disordered, the cavalry would switch to curved swords for the melee

A melee ( or , French: mêlée ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

fighting. Likewise, historians have questioned why Memnon was given command of a cavalry unit at the front line, given his success with leading the Greek mercenaries. A possible motive is that the Persian commanders were jealous of him and did not trust him. Memnon would have been easier for them to control in their midst at the front line. A third point of criticism is the deployment of their infantry far from the frontline. Modern historians have suggested that the Persian commanders did so out of resentment towards the Greek mercenaries, which had defeated the Macedonians at Magnesia the year prior. By defeating Alexander with just their cavalry, they would have regained their pride.

Battle

There are three different accounts of the battle given by the ancient historians Arrian, Plutarch and Diodorus Siculus. Arrian's account is the longest and most detailed, Plutarch's account is shorter but corresponds with Arrian's narrative except for some small differences. The account of Diodorus Siculus however is fundamentally different from that of Arrian and Plutarch.

There are three different accounts of the battle given by the ancient historians Arrian, Plutarch and Diodorus Siculus. Arrian's account is the longest and most detailed, Plutarch's account is shorter but corresponds with Arrian's narrative except for some small differences. The account of Diodorus Siculus however is fundamentally different from that of Arrian and Plutarch.

Account of Arrian

After both armies finished their deployment, there was a moment of silence. Alexander then ordered Amyntas, son of Arrhabeus, to attack the Persian left wing with the Companion cavalry squadron of Socrates (now led by Ptolemy, son of Philip) at the front, followed by the Paeonian cavalry, the ''prodromoi'' and an unspecified infantry unit. Arrian then gives the impression that Alexander advanced at nearly the same time with the remainder of the right wing and the infantry, but later makes it clear that Alexander's attack came after the troops of Amyntas were pushed back. Arrian's source may have done so to make Alexander look more heroic. The Persians answered the charge of the vanguard with volleys of javelins. Amyntas's force was at a disadvantage because they were severely outnumbered and the Persians were defending higher ground at the top of the bank. The Macedonians suffered losses and retreated towards Alexander, who now attacked with the remaining Companion cavalry of the right wing. A. M. Devine reasons that the failure of the attack led by Amyntas was not a mistake, but a ruse to draw the Persian cavalry out of formation as they pursued the retreating force of Amyntas into the riverbed. The disruption of the Persian formation would have made them vulnerable to the second attack led by Alexander in person. There have been different translations and interpretations of Arrian's description of how Alexander executed the attack with his cavalry. Some historians have taken Arrian's description as an attack on the Persian center. J. F. C. Fuller thinks Alexander led his attack in a movement diagonally to the left to attack the left of the Persian center. Similarly, A. B. Bosworth considers this movement to have been directed downstream to the left towards the Persian center. The Macedonian forces would have moved in a diagonal line and eventually formed up in wedge formation as they ascended the eastern bank of the Granicus. Other historians maintain that Alexander attacked the Persian left wing. Ernst Badian thinks that Arrian makes it clear that the Persians had massed their cavalry at the left flank and that Alexander attacked that same mass of cavalry. This would have meant that Alexander must have moved more or less straight ahead. Presumably he would have entered the riverbed at a narrow point, so that his cavalry was in column and vulnerable to attack on their flanks as they ascended the riverbank on the Persian side at a wider point. To prevent this, Alexander would have sent his men towards the left, in the direction of the current, while still in the riverbed. This would have widened the front of his formation so that it would match the Persian formation as they emerged on the other bank. N. G. L. Hammond thinks it was a sideways movement upstream to the right so that the troops would remain in line as they crossed the Granicus. The purpose of this would have been to avoid crossing in disorder and in column, while giving Alexander's cavalry mostly the same formation as the Persian cavalry. A. M. Devine argues that it was not merely an oblique movement, but also an oblique formation. Continuing Arrian's narrative, Alexander and his men engaged the Persians and their leaders in a hard-fought battle. The Macedonians eventually got the upper hand because their lance (the

Continuing Arrian's narrative, Alexander and his men engaged the Persians and their leaders in a hard-fought battle. The Macedonians eventually got the upper hand because their lance (the xyston

The xyston ( grc, ξυστόν "spear, javelin; pointed or spiked stick, goad (lit. 'shaved', a derivative of the verb ξύω "scrape, shave")), was a type of a long thrusting spear in ancient Greece. It measured about long and was probably hel ...

) was more effective in melee than the javelin used by the Persians. During the battle, Alexander himself broke his lance and asked his servant Aretis for another. As Aretis had also broken his during the fighting, Demaratus of Corinth handed his lance to Alexander. Alexander then saw Mithridates, the son-in-law of Darius, leading a cavalry unit. Alexander charged and killed him with a lance thrust to his face. Another Persian noble, Rhosaces, then hit Alexander on the helmet with a sword, but the helmet protected him. Alexander dispatched Rhosaces by thrusting him in the chest with his lance. Sphithridates was about to attack Alexander from behind with his sword, but his sword arm was cut off by Cleitus the Black

Cleitus the Black ( grc-gre, Κλεῖτος ὁ μέλας; c. 375 BC – 328 BC), was an officer of the Macedonian army led by Alexander the Great. He saved Alexander's life at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC and was killed by him in a drun ...

. The other Macedonian cavalry had by then established a foothold on the river bank and reinforced Alexander's force.

At this point in the battle the Macedonian cavalry and the light infantry which was interspersed with them forced back the Persian cavalry. This began on the Persian left flank where Alexander was fighting. Then the center was broken and the Persian cavalry on both wings fled. Alexander did not pursue them far but turned his attention to the Greek mercenaries, who had mostly remained inactive at their original position. The mercenaries were surprised by the turn of events and were attacked by both the Foot Companions from the front and the cavalry from all other directions. They were soon defeated and only a few were able to escape.

Account of Plutarch

Plutarch's account focuses more on the ''

Plutarch's account focuses more on the ''aristeia

An aristeia or aristia (; grc, ἀριστεία , ''"excellence"'') is a scene in the dramatic conventions of epic poetry as in the ''Iliad'', where a hero in battle has his finest moments (''aristos'' = "best"). ''Aristeia'' may result in the de ...

'' of Alexander's personal combat with the Persian leaders and gives less attention to the movements and tactics of the armies. This account mostly corresponds to Arrian's version of events, but there are some differences. According to Plutarch the Persians had stationed both infantry and cavalry at their front line. Alexander lead the first attack against the Persians and there are minor differences in his combat with Rhosaces and Sphithridates. While the cavalry battle was ongoing, the Foot Companions crossed the river and engaged the Persian infantry. After a short confrontation, all except for the Greek mercenaries routed. The mercenaries retreated to a higher position. They asked Alexander to negotiate for their surrender, but Alexander refused this and attacked. The mercenaries fought hard and were responsible for most of the Macedonian casualties.

Account of Diodorus

In the account given by Diodorus, the Macedonian and Persian armies encamped on the opposite banks of the Granicus and did not move for the rest of the day. Alexander then crossed the Granicus unopposed at dawn on the next day. Both armies then formed up and started the battle with their cavalry. Diodorus then describes the personal combat of Alexander with the Persian nobles, which differs slightly from the account of Arrian and Plutarch. When many of the Persian commanders were slain and the Persian cavalry was pushed back everywhere, the Persian cavalry opposite Alexander was routed. The rest of the Persian cavalry joined them in flight. After this, the infantry engaged each other, which soon ended with the rout of the Persian infantry.Modern interpretations

Historian Peter Green, in his 1974 book ''Alexander of Macedon'', proposed a way to reconcile the accounts of Diodorus and Arrian. According to Green's interpretation, the riverbank was guarded by infantry, not cavalry, and Alexander's forces sustained heavy losses in the initial attempt to cross the river and were forced to retire. Alexander then grudgingly accepted Parmenion's advice and crossed the river during the night in an uncontested location, and fought the battle at dawn the next day. The Persian army hurried to the location of Alexander's crossing, with the cavalry reaching the scene of the battle first before the slower infantry, and then the battle continued largely as described by Arrian and Plutarch. Green accounts for the differences between his account and the ancient sources by suggesting that Alexander later covered up his initial failed crossing. Green devoted an entire appendix in support of his interpretation, taking the view that for political reasons, Alexander could not admit even a temporary defeat. Thus, the initial defeat was covered up by his propagandists by a very heroic (and Homeric) charge into the now well-deployed enemy. In his preface to the 2013 reprint, Green conceded that he no longer believed his theory was convincing and that the contradiction could not be explained. Other historians have dismissed the account of Diodorus as incorrect and favor Arrian's and Plutarch's narratives. The description given by Diodorus of a separate cavalry and infantry battle would have been uncharacteristic for the Macedonians, who always coordinated their infantry and cavalry to work together. It is likely that a crossing of the Granicus at night or at dawn would have been detected and opposed by the Persians. Even if an uncontested crossing elsewhere was possible, it might have induced the Persian army to retreat. In that case Alexander would have lost the opportunity to quickly destroy the only Persian army present in Asia Minor at that time. An attack in the afternoon would also have meant that the Persians would have to fight with the sun in their eyes, whereas the Macedonians would have the sun in their eyes if they had attacked at dawn.Casualties

Macedonian army

For the Macedonians, Arrian gives losses of 25 Companion cavalry in the preliminary attack, 60 from the rest of the cavalry and 30 of the infantry, a total of 115 killed. Plutarch gives 34 dead, of which 25 were cavalry and 9 were infantry. Justin mentions 9 infantry and 120 cavalry killed. A. M. Devine observes that the source used by Arrian for the casualties was Ptolemy I, who in turn usedCallisthenes

Callisthenes of Olynthus (; grc-gre, Καλλισθένης; 360327 BCE) was a well-connected Greek historian in Macedon, who accompanied Alexander the Great during his Asiatic expedition. The philosopher Aristotle was Callisthenes's great ...

as a source for the casualties. Plutarch used Aristobulus Aristobulus or Aristoboulos may refer to:

*Aristobulus I (died 103 BC), king of the Hebrew Hasmonean Dynasty, 104–103 BC

*Aristobulus II (died 49 BC), king of Judea from the Hasmonean Dynasty, 67–63 BC

*Aristobulus III of Judea (53 BC–36 BC), ...

as his source. This suggests that Plutarch misunderstood the information, because his 25 dead cavalry are probably the 25 Companions who fell during the preliminary attack. Justin's figures seem to be a confused conflation of both Ptolemy I and Aristobulus. Because the battle was short, A. M. Devine considers Arrian's numbers to be reasonably accurate.

Persian army

Next to the Persian nobles who fell in personal combat with Alexander, many Persian leaders perished in the battle. Arrian mentions Niphates, Petenes, Mithrobuzanes, the satrap ofCappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

, Arbupales, the son of the Darius who was the son of Artaxerxes II

Arses ( grc-gre, Ἄρσης; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and suc ...

, Pharnaces, brother of the wife of Darius, and Omares. Arsites survived and fled into Phrygia, but committed suicide later because he was blamed for the defeat. Diodorus also mentions Atizyes

Atizyes was a Persian satrap of Greater Phrygia under the Achaemenids in 334 BC, when Alexander the Great began his campaign. He is not mentioned in the council of Zelea where the satrap coalition was formed against the invasion, so it is not sure ...

, the satrap of Greater Phrygia as being killed, but also mentions him later as a casualty of the Battle of Issus

The Battle of Issus (also Issos) occurred in southern Anatolia, on November 5, 333 BC between the Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Empire, led by Darius III. It was the second great battle of Alexander's conquest of ...

.

For the Persians, Arrian states that 1,000 cavalry were killed and 2,000 Greek mercenaries were taken prisoner. Plutarch mentions 2,500 cavalry and 20,000 infantry killed. Diodorus gives statistics of 2,000 cavalry and 10,000 infantry killed, as well as 20,000 men who were taken prisoner.

The casualty figures of Plutarch and Diodorus are judged to be impossibly large by A. M. Devine. He considers Arrian's figures of 1,000 cavalry killed and 2,000 captured Greek mercenaries to be reasonably accurate. He takes Arrian's number on the captured mercenaries to imply that the remaining 18,000 were killed, which he dismisses. Based on his theory that there were no more than 4,000 to 5,000 Greek mercenaries, it could possibly mean that 2,000 to 3,000 of them were massacred. This gives a total Persian loss of 5,000 to 6,000.

Aftermath

The 2,000 Greek mercenaries who were captured were sent to Macedon to work the land as slaves. Even though they were Greeks, Alexander felt they had betrayed their fellow Greeks with their service to the Persians. In doing so, they did not abide by the agreement made at the Hellenic League, which compelled the Greeks to fight Persia and not each other. He also sent 300 suits of Persian armour toAthens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

as a votive offering

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally ...

to Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded ...

on the Acropolis. He ordered an inscription to be fixed over them so as to mark the absence of the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

ns in his united Greek army: "Alexander, son of Philip and all the Greeks except the Lacedaemonians, present this offering from the spoils taken from the barbarians inhabiting Asia". A statue group, known as the Granicus Monument, was erected by Alexander in the sanctuary of Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek reli ...

at Dion. This consisted of bronze statues by Lysippus

Lysippos (; grc-gre, Λύσιππος) was a Greek sculptor of the 4th century BC. Together with Scopas and Praxiteles, he is considered one of the three greatest sculptors of the Classical Greek era, bringing transition into the Hellenistic p ...

of Alexander with twenty-five of his companions who had died in the initial cavalry charge, all on horseback. In 146 BC, after the Fourth Macedonian War

The Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by the pretender Andriscus, and the Roman Republic. It was the last of the Macedonian Wars, and was the last war to seriously threaten Roman control of Greece until the Fi ...

, this statue group was taken to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus (c. 188 BC – 116 BC/115 BC) was a statesman and general of the Roman Republic during the second century BC. He was praetor in 148 BC, consul in 143 BC, the Proconsul of Hispania Citerior in 142 BC an ...

, where they were displayed in a portico that he built below the Capitoline Hill

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; it, Campidoglio ; la, Mons Capitolinus ), between the Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn. ...

.

Dascylium

Dascylium, Dascyleium, or Daskyleion ( grc, Δασκύλιον, Δασκυλεῖον), also known as Dascylus, was a town in Anatolia some inland from the coast of the Propontis, at modern Ergili, Turkey. Its site was rediscovered in 1952 and ...

was evacuated by its Persian garrison and occupied by Parmenion. Alexander marched to Sardis

Sardis () or Sardes (; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 ''Sfard''; el, Σάρδεις ''Sardeis''; peo, Sparda; hbo, ספרד ''Sfarad'') was an ancient city at the location of modern ''Sart'' (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, ...

, which surrendered to him. He continued to Ephesus, which was also evacuated by its garrison of Greek mercenaries. When Magnesia and Tralles also offered their surrender, he sent Parmenion to those cities. He sent Lysimachus to the cities in Aeolis

Aeolis (; grc, Αἰολίς, Aiolís), or Aeolia (; grc, Αἰολία, Aiolía, link=no), was an area that comprised the west and northwestern region of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), mostly along the coast, and also several offshore islan ...

and Ionia which were still under Persian control, ordering him to break up the oligarchies there and reinstate democratic government. When Alexander arrived at Miletus the city resisted him, so he besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

it.

The Persian military losses were not disastrous, as a large portion of the army managed to retreat to Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus (; grc, Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός ''Halikarnāssós'' or ''Alikarnāssós''; tr, Halikarnas; Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia. It was located i ...

. On the other hand, the strategic outcome was precarious for the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid satraps had been defeated in Asia Minor before and Sardis had been besieged, but this was the first time that the citadel of Sardis had fallen and that an enemy force could continue its march without significant obstacles until Halicarnassus.

References

Sources

Primary sources * * * * * * Secondary sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of The GranicusGranicus River Granicus may refer to:

* Granicus River, also called Biga River (Turkish: Biga Çayı)

* Battle of the Granicus

The Battle of the Granicus in May 334 BC was the first of three major battles fought between Alexander the Great of Macedon and the ...

334 BC

History of Çanakkale Province

Granicus

Granicus

Invasions of Iran

4th century BC in Iran