Battle of Fort William Henry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The siege of Fort William Henry (3–9 August 1757, french: Bataille de Fort William Henry) was conducted by a

Loudoun's plan depended on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec, so that French troops would not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and would instead be needed to defend the heartland of the province of

Loudoun's plan depended on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec, so that French troops would not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and would instead be needed to defend the heartland of the province of

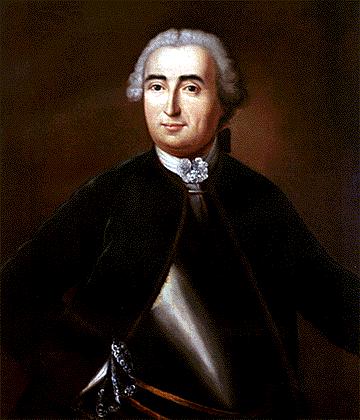

Following the success of his 1756 assault on Fort Oswego, Montcalm had been seeking an opportunity to deal with the British position at Fort William Henry, since it provided the British with a launching point for attacks against

Following the success of his 1756 assault on Fort Oswego, Montcalm had been seeking an opportunity to deal with the British position at Fort William Henry, since it provided the British with a launching point for attacks against

Fort William Henry, built in the fall of 1755, was a roughly square fortification with

Fort William Henry, built in the fall of 1755, was a roughly square fortification with

While at Carillon, the French leadership had difficulty controlling the behaviour of its Indian allies. Although they did stop one group from forcing a British prisoner to

While at Carillon, the French leadership had difficulty controlling the behaviour of its Indian allies. Although they did stop one group from forcing a British prisoner to

While Montcalm's Indian allies had already begun to move south, his advance force of French troops departed from Carillon on 30 July under Lévis' command, travelling overland along Lake George's western shore because the expedition did not have enough boats to carry the entire force. Montcalm and the remaining forces sailed the next day, and met with Lévis for the night at Ganaouske Bay. The next night, Lévis camped just from Fort William Henry, with Montcalm not far behind. Early on the morning of 3 August, Lévis and the Canadians blocked the road between Edward and William Henry, skirmishing with the recently arrived Massachusetts militia. Montcalm summoned Monro to surrender at 11:00 am. Monro refused, and sent messengers south to Fort Edward, indicating the dire nature of the situation and requesting reinforcements. Webb, feeling threatened by Lévis, refused to send any of his estimated 1,600 men north, since they were all that stood between the French and Albany. He wrote to Monro on 4 August that he should negotiate the best terms possible; this communication was intercepted and delivered to Montcalm.

Montcalm, in the meantime, ordered Bourlamaque to begin siege operations. The French opened trenches to the northwest of the fort with the objective of bringing their artillery to bear against the fort's northwest bastion. On 5 August, French guns began firing on the fort from , a spectacle the large Indian contingent relished. The next day a second

While Montcalm's Indian allies had already begun to move south, his advance force of French troops departed from Carillon on 30 July under Lévis' command, travelling overland along Lake George's western shore because the expedition did not have enough boats to carry the entire force. Montcalm and the remaining forces sailed the next day, and met with Lévis for the night at Ganaouske Bay. The next night, Lévis camped just from Fort William Henry, with Montcalm not far behind. Early on the morning of 3 August, Lévis and the Canadians blocked the road between Edward and William Henry, skirmishing with the recently arrived Massachusetts militia. Montcalm summoned Monro to surrender at 11:00 am. Monro refused, and sent messengers south to Fort Edward, indicating the dire nature of the situation and requesting reinforcements. Webb, feeling threatened by Lévis, refused to send any of his estimated 1,600 men north, since they were all that stood between the French and Albany. He wrote to Monro on 4 August that he should negotiate the best terms possible; this communication was intercepted and delivered to Montcalm.

Montcalm, in the meantime, ordered Bourlamaque to begin siege operations. The French opened trenches to the northwest of the fort with the objective of bringing their artillery to bear against the fort's northwest bastion. On 5 August, French guns began firing on the fort from , a spectacle the large Indian contingent relished. The next day a second

Although Montcalm and other French officers attempted to stop further attacks, others did not, and some explicitly refused to provide further protection to the British. At this point, the column dissolved, as some tried to escape the Indian onslaught, while others actively tried to defend themselves. Massachusetts Colonel

Although Montcalm and other French officers attempted to stop further attacks, others did not, and some explicitly refused to provide further protection to the British. At this point, the column dissolved, as some tried to escape the Indian onslaught, while others actively tried to defend themselves. Massachusetts Colonel

On the afternoon after the massacre, most of the Indians left, heading back to their homes. Montcalm was able to secure the release of 500 captives they had taken, but they still took with them another 200. The French remained at the site for several days, destroying what remained of the British works before leaving on 18 August and returning to Fort Carillon.Nester, p. 64 For unknown reasons, Montcalm decided not to follow up his victory with an attack on Fort Edward. Many reasons have been proposed justifying his decision, including the departure of many (but not all) of the Indians, a shortage of provisions, the lack of draft animals to assist in the portage to the Hudson, and the need for the Canadian militia to return home in time to participate in the harvest.Nester, p. 62

Word of the French movements had reached the influential British Indian agent William Johnson on 1 August. Unlike Webb, he acted with haste, and arrived at Fort Edward on 6 August with 1,500 militia and 150 Indians. In a move that infuriated Johnson, Webb refused to allow him to advance toward Fort William Henry, apparently believing a French deserter's report that the French army was 11,000 men strong, and that any attempt at relief was futile given the available forces.Nester, pp. 57–58

On the afternoon after the massacre, most of the Indians left, heading back to their homes. Montcalm was able to secure the release of 500 captives they had taken, but they still took with them another 200. The French remained at the site for several days, destroying what remained of the British works before leaving on 18 August and returning to Fort Carillon.Nester, p. 64 For unknown reasons, Montcalm decided not to follow up his victory with an attack on Fort Edward. Many reasons have been proposed justifying his decision, including the departure of many (but not all) of the Indians, a shortage of provisions, the lack of draft animals to assist in the portage to the Hudson, and the need for the Canadian militia to return home in time to participate in the harvest.Nester, p. 62

Word of the French movements had reached the influential British Indian agent William Johnson on 1 August. Unlike Webb, he acted with haste, and arrived at Fort Edward on 6 August with 1,500 militia and 150 Indians. In a move that infuriated Johnson, Webb refused to allow him to advance toward Fort William Henry, apparently believing a French deserter's report that the French army was 11,000 men strong, and that any attempt at relief was futile given the available forces.Nester, pp. 57–58

The British (and later Americans) never rebuilt anything on the site of Fort William Henry, which lay in ruins for about 200 years. In the 1950s, excavation at the site eventually led to the reconstruction of Fort William Henry as a tourist destination for the town of Lake George.

Many colonial accounts of the time focused on the plundering perpetrated by the Indians, and the fact that those who resisted them were killed, using words like "massacre" even though casualty numbers were uncertain. The later releases of captives did not receive the same level of press coverage. The events of the battle and subsequent killings were depicted in the 1826 novel ''

The British (and later Americans) never rebuilt anything on the site of Fort William Henry, which lay in ruins for about 200 years. In the 1950s, excavation at the site eventually led to the reconstruction of Fort William Henry as a tourist destination for the town of Lake George.

Many colonial accounts of the time focused on the plundering perpetrated by the Indians, and the fact that those who resisted them were killed, using words like "massacre" even though casualty numbers were uncertain. The later releases of captives did not receive the same level of press coverage. The events of the battle and subsequent killings were depicted in the 1826 novel '' Historians disagree on where to assign responsibility for the Indian actions.

Historians disagree on where to assign responsibility for the Indian actions.

An account of two attacks on Fort William Henry

The Siege of Fort William Henry, Video Documentary

{{Authority control Fort William Henry 1757 in North America Fort William Henry Fort William Henry 1757 Fort William Henry 1757 Fort William Henry 1757 Massacres by Native Americans 1757 in the Province of New York Massacres committed by France Massacres in 1757 Battles won by indigenous peoples of the Americas

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

force led by Louis-Joseph de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

against the British-held Fort William Henry. The fort, located at the southern end of Lake George, on the frontier between the British Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

and the French Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

, was garrisoned by a poorly supported force of British regulars and provincial militia led by Lieutenant Colonel George Monro.

After several days of bombardment, Monro surrendered to Montcalm, whose force included nearly 2,000 Indians from various tribes. The terms of surrender included the withdrawal of the garrison to Fort Edward, with specific terms that the French military protect the British from the Indians as they withdrew from the area.

In one of the most notorious incidents of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, Montcalm's Indian allies violated the agreed terms of surrender and attacked the departing British column, which had been deprived of ammunition, as it left the fort. They killed and scalped numerous soldiers and civilians, took as captives women, children, servants, and slaves, and slaughtered sick and wounded prisoners. Early accounts of the events called it a massacre and implied that as many as 1,500 people were killed, although it is unlikely more than 200 people (less than 10% of the British fighting strength) were actually killed in the massacre.

The exact role of Montcalm and other French officers present in encouraging or defending against the actions of their allies, and the total number of casualties incurred as a result of their actions, is a subject of historical debate. The memory of the killings influenced the actions of British military commanders, especially those of General Jeffery Amherst, for the remainder of the war.

Background

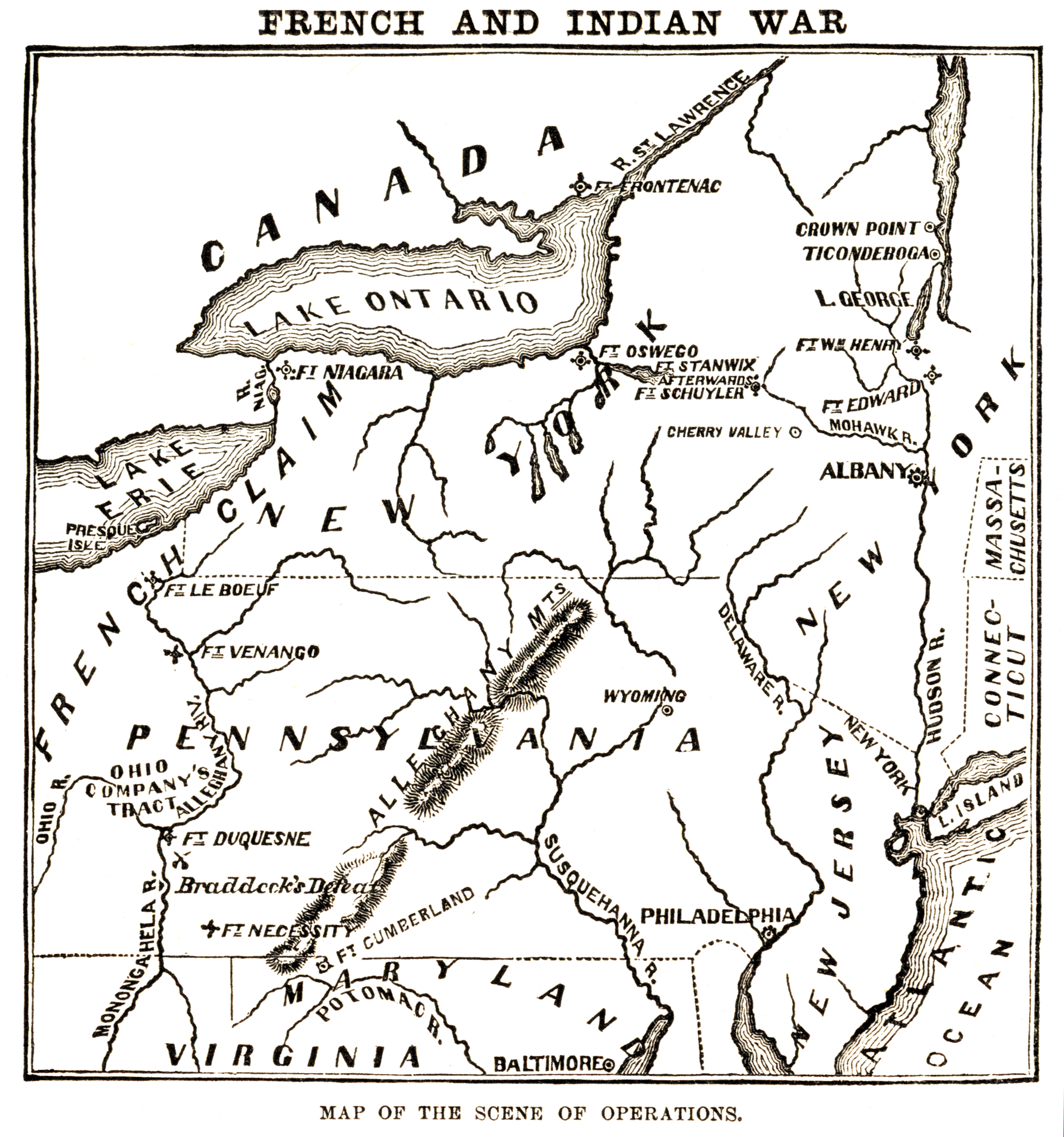

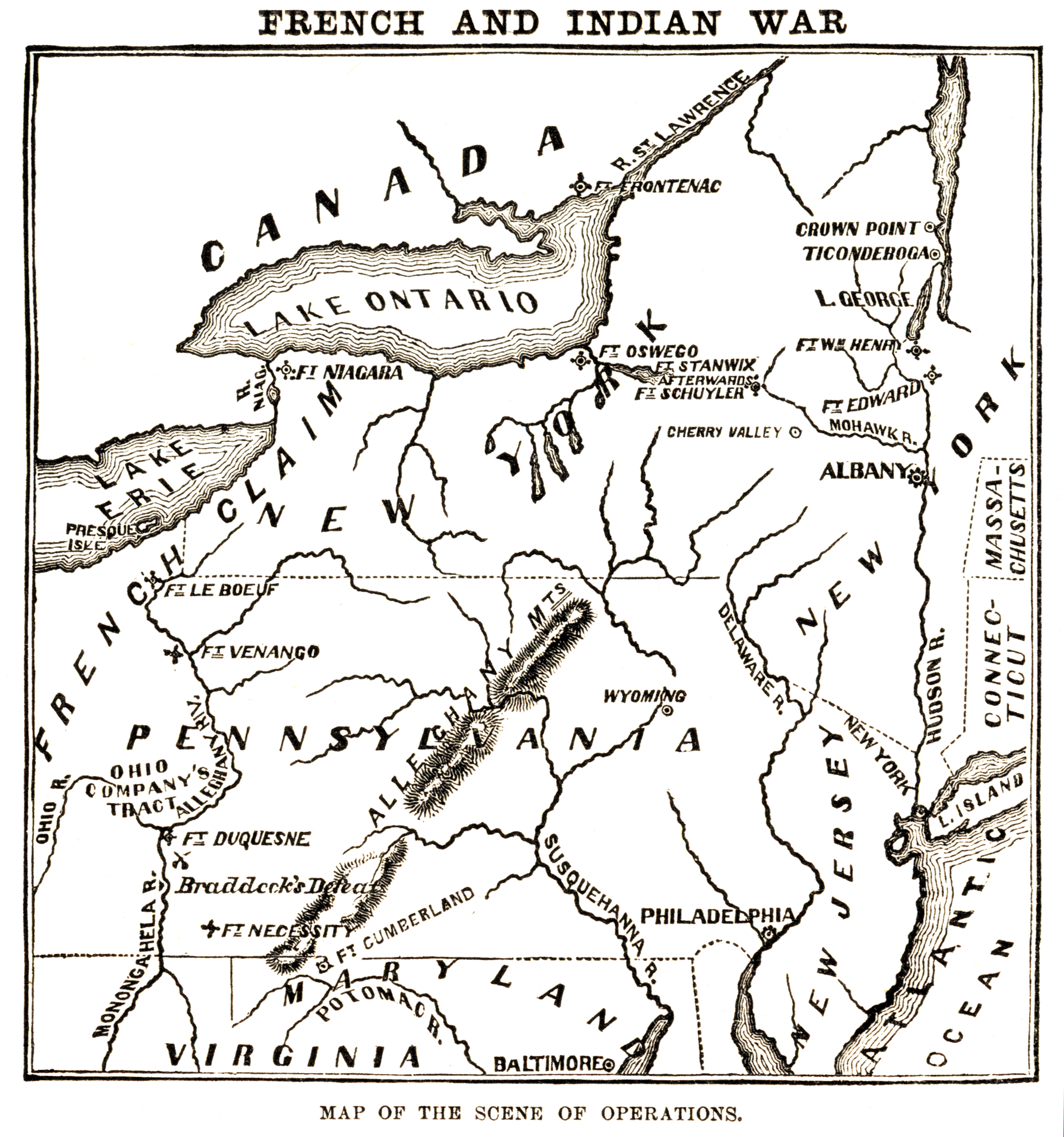

TheFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

started in 1754 over territorial disputes between the North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

n colonies of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

in areas that are now western Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and upstate New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. The war began after George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

attacked, captured, and massacred French forces at the Battle of Jumonville Glen, while Britain and France were still at peace. The first few years of the war did not go particularly well for the British. A major expedition by General Edward Braddock

Major-General Edward Braddock (January 1695 – 13 July 1755) was a British officer and commander-in-chief for the Thirteen Colonies during the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American front of what is known in Europ ...

in 1755 ended in disaster

A disaster is a serious problem occurring over a short or long period of time that causes widespread human, material, economic or environmental loss which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources ...

, and British military leaders were unable to mount any campaigns the following year. In a major setback, a French and Indian army led by General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

captured the garrison and destroyed fortifications in the Battle of Fort Oswego

The Battle of Fort Oswego was one in a series of early French victories in the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War won in spite of New France's military vulnerability. During the week of August 10, 1756, a force of regulars and Can ...

in August 1756. In July 1756 the Earl of Loudoun

Earl of Loudoun (pronounced "loud-on" ), named after Loudoun in Ayrshire, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1633 for John Campbell, 2nd Lord Campbell of Loudoun, along with the subsidiary title Lord Tarrinzean and Mauchlin ...

arrived to take command of the British forces in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

, replacing William Shirley, who had temporarily assumed command after Braddock's death.

British planning

Loudoun's plan for the 1757 campaign was submitted to the government inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in September 1756, and was focused on a single expedition aimed at the heart of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

, the city of Quebec. It called for a purely defensive postures along the frontier with New France, including the contested corridor of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

and Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

between Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

and Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

.Pargellis, p. 211 Following the Battle of Lake George in 1755, the French had begun construction of Fort Carillon (now known as Fort Ticonderoga) near the southern end of Lake Champlain, while the British had built Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George, and Fort Edward on the Hudson River, about south of Fort William Henry (all three forts are in present-day New York). The area between William Henry and Carillon was a wilderness dominated by Lake George that historian Ian Steele described as "a military waterway that left opposing cannons only a few days apart."

Loudoun's plan depended on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec, so that French troops would not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and would instead be needed to defend the heartland of the province of

Loudoun's plan depended on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec, so that French troops would not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and would instead be needed to defend the heartland of the province of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

along the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

. However, political turmoil in London over the progress of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

both in North America and in Europe resulted in a change of power, with William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

rising to take control over military matters. Loudoun consequently did not receive any feedback from London on his proposed campaign until March 1757. Before this feedback arrived he developed plans for the expedition to Quebec, and worked with the provincial governors of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

to develop plans for a coordinated defence of the frontier, including the allotment of militia quotas to each province.

When William Pitt's instructions finally reached Loudoun in March 1757, they called for the expedition to first target Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour ...

on the Atlantic coast of Île Royale

The Salvation Islands (french: Îles du Salut, so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland; sometimes mistakenly called Safety Islands) are a group of small islands of volcanic origin about off the coast of Fre ...

, now known as Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

. Although this did not materially affect the planning of the expedition, it was to have significant consequences on the frontier. The French forces on the Saint Lawrence would be too far from Louisbourg to support it, and would consequently be free to act elsewhere. Loudoun assigned his best troops to the Louisbourg expedition, and placed Brigadier General Daniel Webb in command of the New York frontier. He was given about 2,000 regulars, primarily from the 35th and 60th (Royal American) Regiments. The provinces were to supply Webb with about 5,000 militia.

French planning

Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, presently known as Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it ...

(now known as Fort Ticonderoga). He was initially hesitant to commit his limited resources against Fort William Henry without knowing more about the disposition of British forces. Intelligence provided by spies in London arrived in the spring, indicating that the British target was probably Louisbourg. This suggested that troop levels on the British side of the frontier might be low enough to make an attack on Fort William Henry feasible.Nester, p. 52 This idea was further supported after the French questioned deserters and captives taken during periodic scouting and raiding expeditions that both sides conducted, including one resulting in the January Battle on Snowshoes.

As early as December 1756, New France's governor, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, began the process of recruiting Indians for the following summer's campaign. Fueled by stories circulated by Indian participants in the capture of Oswego, this drive was highly successful, drawing nearly 1,000 warriors from the ''Pays d'en Haut

The ''Pays d'en Haut'' (; ''Upper Country'') was a territory of New France covering the regions of North America located west of Montreal. The vast territory included most of the Great Lakes region, expanding west and south over time into the ...

'' (the more remote regions of New France) to Montreal by June 1757.Nester, p. 54 Another 800 Indians were recruited from tribes that lived closer to the Saint Lawrence.

British preparations

Fort William Henry, built in the fall of 1755, was a roughly square fortification with

Fort William Henry, built in the fall of 1755, was a roughly square fortification with bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

s on the corners, in a design that was intended to repel Indian attacks but was not necessarily sufficient to withstand attack from an enemy that had artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

. Its walls were thick, with log facings surrounding an earthen filling. Inside the fort were wooden barracks two stories high, built around the parade ground. Its magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

was in the northeast bastion, and its hospital was located in the southeast bastion. The fort was surrounded on three sides by a dry moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that is dug and surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive ...

, with the fourth side sloping down to the lake. The only access to the fort was by a bridge across the moat. The fort was capable of housing only four to five hundred men; additional troops were quartered in an entrenched camp southeast of the fort, near the site of the 1755 Battle of Lake George.

During the winter of 1756–57, Fort William Henry was garrisoned by several hundred men from the 44th Foot under Major Will Eyre. In March 1757 the French sent an army of 1,500 to attack the fort under the command of the governor's brother, Pierre de Rigaud. Composed primarily of colonial troupes de la marine, militia, and Indians, and without heavy weapons, they besieged the fort for four days, destroying outbuildings and many watercraft before retreating. Eyre and his men were replaced by Lieutenant Colonel George Monro and the 35th Foot in the spring. Monro established his headquarters in the entrenched camp, where most of his men were located.Nester, p. 55

French preparations

The Indians that assembled at Montreal were sent south to Fort Carillon, where they joined the French regiments of Béarn and Royal Roussillon underFrançois-Charles de Bourlamaque

François-Charles de Bourlamaque (the surname can also be seen as Burlamaqui) (1716 – 1764) was a French military leader and Governor of Guadeloupe from 1763.

Biography

His father Francesco Burlamacchi was born in Lucca, Tuscany. He began as ...

, and those of La Sarre

La Sarre is a town in northwestern Quebec, Canada, and is the most populous town and seat of the Abitibi-Ouest Regional County Municipality. It is located at the intersection of Routes 111 and 393, on the La Sarre River, a tributary of Lake ...

, Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne (, ; oc, Guiana ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the archdiocese of Bordeaux.

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transformation o ...

, Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately ...

, and la Reine La Reine can refer to

Organizations

* Régiment de La Reine, a regiment of the French Army of the Ancien Régime

Places

* La Reine, Quebec, a municipality in Quebec, Canada

* La Reine, a populated place in the commune of Saint-Priest-des-Champs, ...

under François de Gaston, Chevalier de Lévis. Combined with the troupes de la marine, militia companies, and the arriving Indians, the force accumulated at Carillon amounted to 8,000 men.Parkman, pp. 489–492

While at Carillon, the French leadership had difficulty controlling the behaviour of its Indian allies. Although they did stop one group from forcing a British prisoner to

While at Carillon, the French leadership had difficulty controlling the behaviour of its Indian allies. Although they did stop one group from forcing a British prisoner to run the gantlet

Run the Gantlet (1968–1986) was an American Champion Thoroughbred racehorse and noted sire.

Background

He was out of the mare First Feather, whom owner Paul Mellon had purchased as a yearling at a then record price of $90,000 for a filly. ...

, a group of Ottawas were not stopped when it was observed that they were ritually cannibalizing another prisoner. French authorities were also frustrated in their ability to limit the Indians' taking of more than their allotted share of rations. Montcalm's aide, Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (, , ; 12 November 1729 – August 1811) was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of the British explorer James Cook, he took part in the Seven Years' War in North America and the American Revolutio ...

, observed that attempts to curb this activity would have resulted in the loss of some of these forces. In another prelude of things to come, many prisoners were taken on 23 July in the Battle of Sabbath Day Point

The Battle of Sabbath Day Point took place on 23 July 1757 just off the shore of Sabbath Day Point, Lake George, New York and ended in a French victory. The battle (actually better described as an ambush), pitched approximately 450 French and al ...

, some of whom were also ritually cannibalized before Montcalm managed to convince the Indians instead to send the captives to Montreal to be sold as slaves.

Prelude

Webb, who commanded the area from his base at Fort Edward, received intelligence in April that the French were accumulating resources and troops at Carillon. News of continued French activity arrived with a captive taken in mid-July. Following an attack byJoseph Marin de la Malgue Joseph Marin de la Malgue (February 1719 – 1774) was the son of Charles-Paul Marin de la Malgue and continued on in the family military and exploration tradition, entering the colonial regular troops at the age of 13. He spent the next 13 years ...

on a work crew near Fort Edward on 23 July, Webb travelled to Fort William Henry with a party of Connecticut rangers led by Major Israel Putnam, and sent a detachment of them onto the lake for reconnaissance. They returned with word that Indians were encamped on islands in the lake about from the fort. Swearing Putnam and his rangers to secrecy, Webb returned to Fort Edward, and on 2 August sent Lieutenant Colonel John Young with 200 regulars and 800 Massachusetts militia to reinforce the garrison at William Henry. This raised the size of the garrison to about 2,500, although several hundred of these were ill, some with smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

.Steele, p. 69

Order of Battle

British Forces * British Forces, commanded byLieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

George Monro

** 35th Regiment of Foot

The 35th (Royal Sussex) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1701. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 107th (Bengal Infantry) Regiment of Foot to form the Royal Sussex Regiment in 1881.

His ...

** 1st Battalion, Massachusetts Provincial Forces (about 450 x men), commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

Timothy Ruggles

Timothy Dwight Ruggles (October 20, 1711 – August 4, 1795) was an American colonial military leader, jurist, and politician. He was a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 and later a Loyalist during the American Revolutionary War.

Earl ...

** 2nd Battalion, Massachusetts Provincial Forces (about 450 x men), commanded by Colonel Moses Titcomb

** 3rd Battalion, Massachusetts Provincial Forces (about 450 x men), commanded by Colonel Ephraim Williams (KIA)

** 1st Battalion, Connecticut Provincial Forces (about 450 x men), commanded by Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Phineas Lyman

Phineas Lyman (1716–1774) was a colonial American soldier known for his service in the provincial British Army of the French and Indian War. He later led a group of New England veterans of the war to settle in the new colony of West Florida wh ...

** 2nd Battalion, Connecticut Provincial Forces (about 450 x men), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

Whiting

** 5 x Companies, Rhode Island Provincial Forces (about 250 x men), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Cole

** 3 x Companies, New York Provincial Forces (about 200 x men)

** 250 x Mohawk Native Americans

French Forces

* French Forces, commanded by '' Général de Division'' Ludwig August, Baron von Dieskau

** 2 x Companies, Régiment de Languedoc

** 2 x Companies, Régiment de La Reine

The Régiment de la Reine (''Queen's Regiment'') was a French Army infantry regiment active in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is principally known for its role in the Seven Years' War, when it served in the North American theatre.

Early histo ...

** 12 x Men, Troupes de la Marine

** 684 x Canadian Militiamen (unknown battalions and brigades)

** Approximately 1800 Indians from the Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

, Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

, Potawatomis and Nipissing tribes

* En-route: Corps Royal from the Fortress of Louisbourg

** 6 x Officers

** 400 x Recruits

** 20 x Artillerymen

** 2 x Battalions, Régiment de Berry

Siege

While Montcalm's Indian allies had already begun to move south, his advance force of French troops departed from Carillon on 30 July under Lévis' command, travelling overland along Lake George's western shore because the expedition did not have enough boats to carry the entire force. Montcalm and the remaining forces sailed the next day, and met with Lévis for the night at Ganaouske Bay. The next night, Lévis camped just from Fort William Henry, with Montcalm not far behind. Early on the morning of 3 August, Lévis and the Canadians blocked the road between Edward and William Henry, skirmishing with the recently arrived Massachusetts militia. Montcalm summoned Monro to surrender at 11:00 am. Monro refused, and sent messengers south to Fort Edward, indicating the dire nature of the situation and requesting reinforcements. Webb, feeling threatened by Lévis, refused to send any of his estimated 1,600 men north, since they were all that stood between the French and Albany. He wrote to Monro on 4 August that he should negotiate the best terms possible; this communication was intercepted and delivered to Montcalm.

Montcalm, in the meantime, ordered Bourlamaque to begin siege operations. The French opened trenches to the northwest of the fort with the objective of bringing their artillery to bear against the fort's northwest bastion. On 5 August, French guns began firing on the fort from , a spectacle the large Indian contingent relished. The next day a second

While Montcalm's Indian allies had already begun to move south, his advance force of French troops departed from Carillon on 30 July under Lévis' command, travelling overland along Lake George's western shore because the expedition did not have enough boats to carry the entire force. Montcalm and the remaining forces sailed the next day, and met with Lévis for the night at Ganaouske Bay. The next night, Lévis camped just from Fort William Henry, with Montcalm not far behind. Early on the morning of 3 August, Lévis and the Canadians blocked the road between Edward and William Henry, skirmishing with the recently arrived Massachusetts militia. Montcalm summoned Monro to surrender at 11:00 am. Monro refused, and sent messengers south to Fort Edward, indicating the dire nature of the situation and requesting reinforcements. Webb, feeling threatened by Lévis, refused to send any of his estimated 1,600 men north, since they were all that stood between the French and Albany. He wrote to Monro on 4 August that he should negotiate the best terms possible; this communication was intercepted and delivered to Montcalm.

Montcalm, in the meantime, ordered Bourlamaque to begin siege operations. The French opened trenches to the northwest of the fort with the objective of bringing their artillery to bear against the fort's northwest bastion. On 5 August, French guns began firing on the fort from , a spectacle the large Indian contingent relished. The next day a second battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

opened fire from further along the same trench, creating a crossfire. The effect of the garrison's return fire was limited to driving French guards from the trenches, and some of the fort's guns either were dismounted or burst owing to the stress of use.Steele, pp. 100–102 On 7 August, Montcalm sent Bougainville to the fort under a truce flag to deliver the intercepted dispatch. By then the fort's walls had been breached, many of its guns were useless, and the garrison had taken many casualties. After another day of bombardment by the French, during which their trenches approached another , Monro raised the white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symbolize ...

to open negotiations.Nester, p. 59

Massacre

The terms of surrender were that the British and their camp followers would be allowed to withdraw, under French escort, to Fort Edward, with the full honours of war, on condition that they refrain from fighting for 18 months. They were allowed to keep theirmusket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

s and a single symbolic cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

, but no ammunition. In addition, British authorities were to release French prisoners within three months.

Montcalm, before agreeing to these terms, tried to make sure that his Indian allies understood them, and that the chiefs would undertake to restrain their men. This process was complicated by the diversity within the Indian camp, which included some warriors who spoke languages not understood by any European present. The British garrison was then evacuated from the fort to the entrenched camp, and Monro was quartered in the French camp. The Indians then entered the fort and plundered it, butchering some of the wounded and sick that the British had left behind. The French guards posted around the entrenched camp were only somewhat successful at keeping the Indians out of that area, and it took much effort to prevent plunder and scalping there. Montcalm and Monro initially planned to march the prisoners south the following morning, but after seeing the Indian bloodlust, decided to attempt the march that night. When the Indians became aware that the British were getting ready to move, many of them massed around the camp, causing the leaders to call off the march until morning.

The next morning, even before the British column began to form up for the march to Fort Edward, the Indians renewed attacks on the largely defenceless British. At 5 a.m., Indians entered huts in the fort housing wounded British who were supposed to be under the care of French doctors, and killed and scalped them.Nester, p. 60 Monro complained that the terms of capitulation had been violated, but his contingent was forced to surrender some of its baggage in order to be able even to begin the march. As they marched off, they were harassed by the swarming Indians, who snatched at them, grabbing for weapons and clothing, and pulling away with force those that resisted their actions, including many of the women, children, servants and slaves. As the last of the men left the encampment, a war whoop sounded, and a contingent of Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

warriors seized several men at the rear of the column.

Although Montcalm and other French officers attempted to stop further attacks, others did not, and some explicitly refused to provide further protection to the British. At this point, the column dissolved, as some tried to escape the Indian onslaught, while others actively tried to defend themselves. Massachusetts Colonel

Although Montcalm and other French officers attempted to stop further attacks, others did not, and some explicitly refused to provide further protection to the British. At this point, the column dissolved, as some tried to escape the Indian onslaught, while others actively tried to defend themselves. Massachusetts Colonel Joseph Frye

Joseph Frye (March 19, 1712 – July 25, 1794) was a renowned military leader from colonial Maine (then a part of Massachusetts).

Life

Born in Andover, Massachusetts, he obtained the rank of general in the Massachusetts militia after servi ...

reported that he was stripped of much of his clothing and repeatedly threatened. He fled into the woods, and did not reach Fort Edward until 12 August.

Estimates of the numbers killed, wounded, and taken captive during this time vary widely. Ian Steele has compiled estimates ranging from 200 to 1,500. His detailed reconstruction of the siege and its aftermath indicates that the final tally of British missing and dead ranges from 69 to 184, at most 7.5% of the 2,308 who surrendered.Steele, p. 144

Aftermath

On the afternoon after the massacre, most of the Indians left, heading back to their homes. Montcalm was able to secure the release of 500 captives they had taken, but they still took with them another 200. The French remained at the site for several days, destroying what remained of the British works before leaving on 18 August and returning to Fort Carillon.Nester, p. 64 For unknown reasons, Montcalm decided not to follow up his victory with an attack on Fort Edward. Many reasons have been proposed justifying his decision, including the departure of many (but not all) of the Indians, a shortage of provisions, the lack of draft animals to assist in the portage to the Hudson, and the need for the Canadian militia to return home in time to participate in the harvest.Nester, p. 62

Word of the French movements had reached the influential British Indian agent William Johnson on 1 August. Unlike Webb, he acted with haste, and arrived at Fort Edward on 6 August with 1,500 militia and 150 Indians. In a move that infuriated Johnson, Webb refused to allow him to advance toward Fort William Henry, apparently believing a French deserter's report that the French army was 11,000 men strong, and that any attempt at relief was futile given the available forces.Nester, pp. 57–58

On the afternoon after the massacre, most of the Indians left, heading back to their homes. Montcalm was able to secure the release of 500 captives they had taken, but they still took with them another 200. The French remained at the site for several days, destroying what remained of the British works before leaving on 18 August and returning to Fort Carillon.Nester, p. 64 For unknown reasons, Montcalm decided not to follow up his victory with an attack on Fort Edward. Many reasons have been proposed justifying his decision, including the departure of many (but not all) of the Indians, a shortage of provisions, the lack of draft animals to assist in the portage to the Hudson, and the need for the Canadian militia to return home in time to participate in the harvest.Nester, p. 62

Word of the French movements had reached the influential British Indian agent William Johnson on 1 August. Unlike Webb, he acted with haste, and arrived at Fort Edward on 6 August with 1,500 militia and 150 Indians. In a move that infuriated Johnson, Webb refused to allow him to advance toward Fort William Henry, apparently believing a French deserter's report that the French army was 11,000 men strong, and that any attempt at relief was futile given the available forces.Nester, pp. 57–58

Return of captives

On 14 August, Montcalm wrote letters to Loudoun and Webb, apologising for the behaviour of the Indians, but also attempting to justify it.Nester, p. 64 Many captives that were taken to Montreal by the Indians were also eventually repatriated through prisoner exchanges negotiated by Governor Vaudreuil. On 27 September a small British fleet left Quebec, carryingparoled

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

or exchanged prisoners taken in a variety of actions including those at Fort William Henry and Oswego. When the fleet arrived at Halifax, about 300 people captured at Fort William Henry were returned to the colonies. The fleet continued to Europe, where a few more former captives were released; some of these also eventually returned to the colonies.

Consequences

General Webb was recalled because of his actions; William Johnson wrote that Webb was "the only Englishman ever knew who was a coward."Starbuck, p. 14 Lord Loudoun was also recalled, although this occurred primarily because of the failure of the Louisbourg expedition. Colonel Monro died in November 1757, ofapoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

that some historians have suggested was caused by anger over Webb's failure to support him.

Lord Loudoun, upset over the event, delayed implementing the release of French prisoners promised as part of the terms of surrender. General James Abercrombie, who succeeded Loudoun as commander-in-chief, was asked by paroled members of the 35th Foot to void the agreement so that they would be free to serve in 1758; this he did, and they went on to serve under General Jeffery Amherst in his successful British expedition against Louisbourg in 1758. Amherst, who also presided over the surrender of Montreal in 1760, refused the surrendering garrisons at Louisbourg and Montreal the normal honours of war, due in part to the French failure to uphold the terms of capitulation in this action.

Legacy

The British (and later Americans) never rebuilt anything on the site of Fort William Henry, which lay in ruins for about 200 years. In the 1950s, excavation at the site eventually led to the reconstruction of Fort William Henry as a tourist destination for the town of Lake George.

Many colonial accounts of the time focused on the plundering perpetrated by the Indians, and the fact that those who resisted them were killed, using words like "massacre" even though casualty numbers were uncertain. The later releases of captives did not receive the same level of press coverage. The events of the battle and subsequent killings were depicted in the 1826 novel ''

The British (and later Americans) never rebuilt anything on the site of Fort William Henry, which lay in ruins for about 200 years. In the 1950s, excavation at the site eventually led to the reconstruction of Fort William Henry as a tourist destination for the town of Lake George.

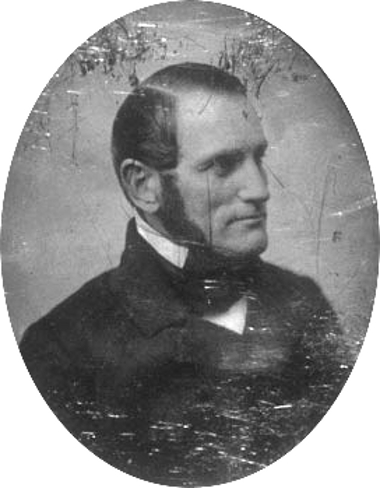

Many colonial accounts of the time focused on the plundering perpetrated by the Indians, and the fact that those who resisted them were killed, using words like "massacre" even though casualty numbers were uncertain. The later releases of captives did not receive the same level of press coverage. The events of the battle and subsequent killings were depicted in the 1826 novel ''The Last of the Mohicans

''The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757'' is a historical romance written by James Fenimore Cooper in 1826.

It is the second book of the '' Leatherstocking Tales'' pentalogy and the best known to contemporary audiences. '' The Pathfinde ...

'' by James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought ...

and in film adaptations of the book. Cooper's description of the events contains numerous inaccuracies, but his work, and the sometimes lurid descriptions of the event by early historians like Benson Lossing

Benson John Lossing (February 12, 1813 – June 3, 1891) was a prolific and popular American historian, known best for his illustrated books on the American Revolution and American Civil War and features in '' Harper's Magazine''. He was a ...

and Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman Jr. (September 16, 1823 – November 8, 1893) was an American historian, best known as author of '' The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life'' and his monumental seven-volume '' France and England in North Am ...

, led to the belief that many more people died than actually did. Lossing wrote that "fifteen hundred eoplewere butchered or carried into hopeless captivity", when many more were captured than killed, and even many of those captured were eventually freed.

Historians disagree on where to assign responsibility for the Indian actions.

Historians disagree on where to assign responsibility for the Indian actions. Francis Jennings

Francis "Fritz" Jennings (1918November 17, 2000) was an American historian, best known for his works on the colonial history of the United States. He taught at Cedar Crest College from 1968 to 1976, and at the Moore College of Art from 1966 to ...

contends that Montcalm anticipated what was going to happen, deliberately ignored it when it did happen, and stepped in only after the atrocities were well under way. In his opinion, the account by Bougainville, who left for Montreal on the night of 9 August and was not present at the massacre, was written as a whitewash

Whitewash, or calcimine, kalsomine, calsomine, or lime paint is a type of paint made from slaked lime (calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or chalk calcium carbonate, (CaCO3), sometimes known as "whiting". Various other additives are sometimes used.

...

to protect Montcalm. Parkman is more vigorous in his defence of Montcalm, claiming that he and other French officers did what they could to prevent atrocities, but were powerless to stop the onslaught.

Ian Steele notes that two primary accounts dominate much of the historical record. The first is the record compiled by Montcalm, including the terms of surrender and his letters to Webb and Loudoun, which received wide publication in the colonies (both French and British) and in Europe. The second was the 1778 publication of a book by Jonathan Carver, an explorer who served in the Massachusetts militia and was present at the siege. According to Steele, Carver originated, without any supporting analysis or justification, the idea that as many as 1,500 people had been "killed or made prisoner" in his widely popular work. Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

president Timothy Dwight, in a history published posthumously in 1822, apparently coined the phrase "massacre at Fort William Henry", based on Carver's work; his book and Carver's were likely influences on Cooper, and tended to fault Montcalm for the Indian transgressions. Steele himself adopts a more nuanced view of the underlying cause of the massacre. Montcalm and the French leaders repeatedly promised the Indians opportunities for the glory and trophies of war, including plunder, scalping, and the taking of captives.Steele, p. 184 In the aftermath of the Battle of Sabbath Day Point

The Battle of Sabbath Day Point took place on 23 July 1757 just off the shore of Sabbath Day Point, Lake George, New York and ended in a French victory. The battle (actually better described as an ambush), pitched approximately 450 French and al ...

, captives taken were ransomed, meaning the Indians had no visible trophies. The terms of surrender at Fort William Henry effectively denied the Indians appreciable opportunities for plunder: the war provisions were claimed by the French army, and personal effects of the British were to stay with them, leaving nothing for the Indians. According to Steele, this decision bred resentment, as it appeared that the French were conspiring with their enemies (the British) against their friends (the Indians), leaving them without any promised war trophies.Steele, p. 185

Notes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

An account of two attacks on Fort William Henry

The Siege of Fort William Henry, Video Documentary

{{Authority control Fort William Henry 1757 in North America Fort William Henry Fort William Henry 1757 Fort William Henry 1757 Fort William Henry 1757 Massacres by Native Americans 1757 in the Province of New York Massacres committed by France Massacres in 1757 Battles won by indigenous peoples of the Americas