Battle of Chantilly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

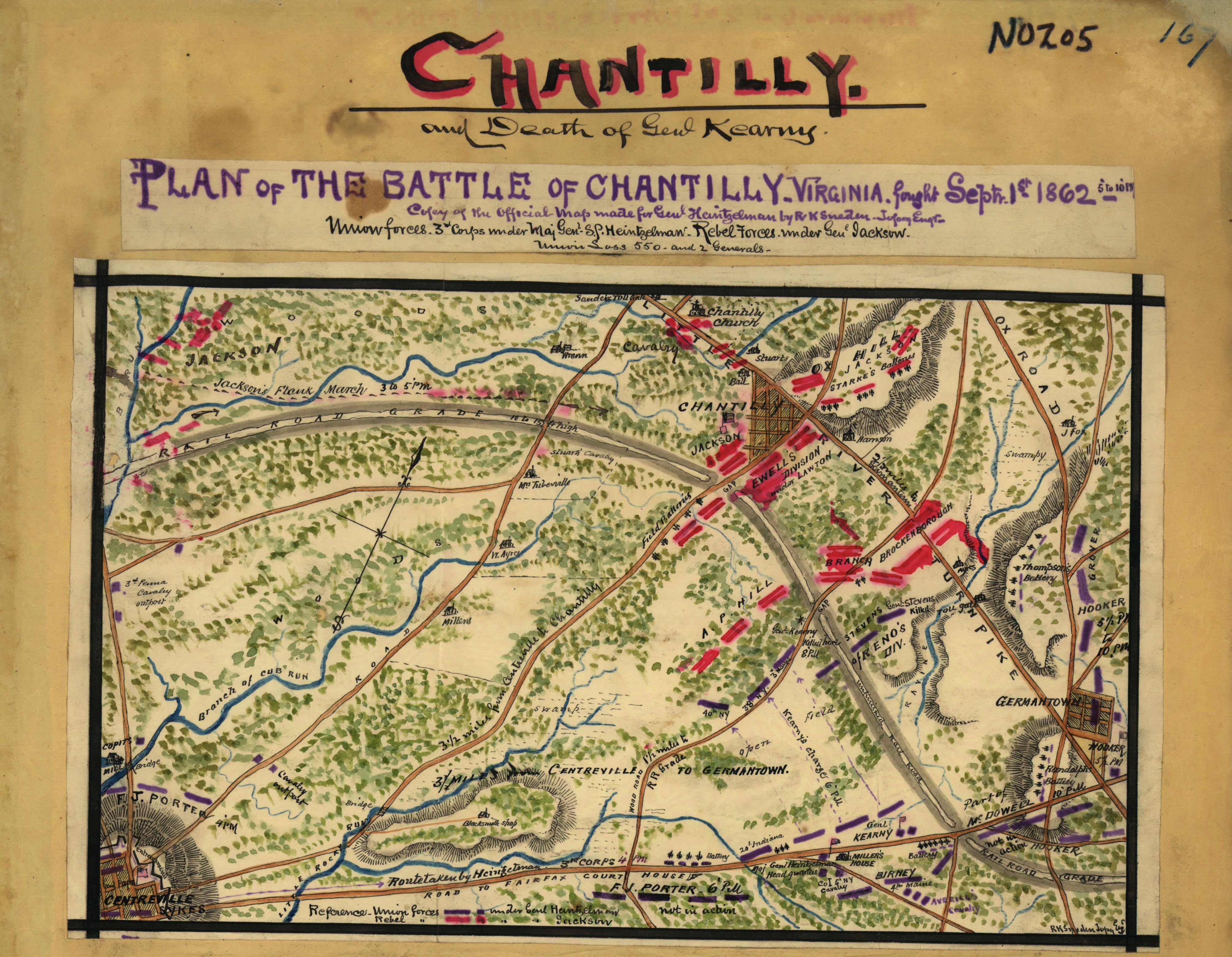

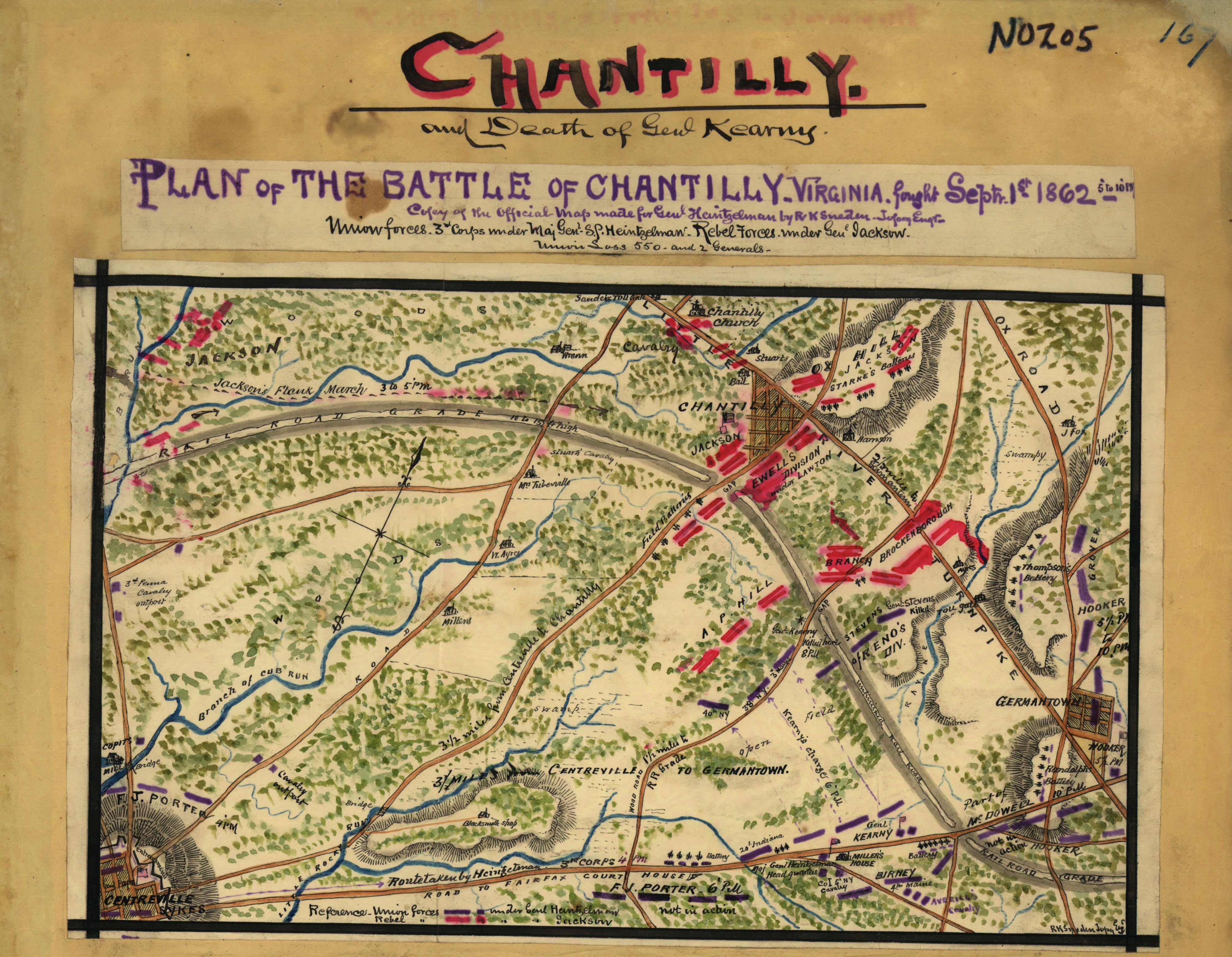

The Battle of Chantilly (or Ox Hill, the Confederate name) took place on September 1, 1862, in Fairfax County, Virginia, as the concluding battle of the Northern Virginia Campaign of the American Civil War. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps of the

On the morning of September 1, Pope ordered Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner of the

On the morning of September 1, Pope ordered Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner of the  A severe thunderstorm erupted about this time, resulting in limited visibility and an increased dependence on the bayonet, as the rain soaked the ammunition of the infantry and made it useless. Kearny arrived about this time with his division to find Stevens' units disorganized. Perceiving a gap in the line he deployed Brig. Gen.

A severe thunderstorm erupted about this time, resulting in limited visibility and an increased dependence on the bayonet, as the rain soaked the ammunition of the infantry and made it useless. Kearny arrived about this time with his division to find Stevens' units disorganized. Perceiving a gap in the line he deployed Brig. Gen.

Library of Congress

* Hennessy, John J. ''Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. . * Ropes, John Codman. ''The Army in the Civil War''. Vol. 4, ''The Army under Pope''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1881. . * Salmon, John S. ''The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. . * Taylor, Paul. ''He Hath Loosed the Fateful Lightning: The Battle of Ox Hill (Chantilly), September 1, 1862''. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishers, 2003. .

CWSAC Report Update

* Welker, David A. "Tempest at Ox Hill: The Battle of Chantilly." New York: DaCapo, 2002. .

Animated maps, histories, photos, and preservation news. (

''The Battle of Chantilly (Ox Hill)'', a docudrama about the battle

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chantilly

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

attempted to cut off the line of retreat of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''U ...

Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia, ...

following the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederat ...

but was attacked by two Union divisions. During the ensuing battle, Union division commanders Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

and Philip Kearny

Philip Kearny Jr. (; June 1, 1815 – September 1, 1862) was a United States Army officer, notable for his leadership in the Mexican–American War and American Civil War. He was killed in action in the 1862 Battle of Chantilly.

Early life and ...

were both killed, but the Union attack halted Jackson's advance.

Background

Defeated in theSecond Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederat ...

on August 30, Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''U ...

Maj. Gen. John Pope ordered his Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia, ...

to retreat to Centreville. The movement began after dark, with Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's III Corps providing cover. The army crossed Bull Run and the last troops across, Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil ...

's I Corps, destroyed Stone Bridge behind them. Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

decided not to press the advantage gained that day, largely because he knew his Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

was exhausted from two weeks of nearly constant marching and nearly three days of battle, so the Union retreat went unmolested. Lee's decision also allowed the Army of Virginia's II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

, under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, to consolidate with the bulk of Pope's army, marching in from Bristoe Station, where they had been guarding the army's trains. More importantly, Lee's decision bought time for the Union to push to the front the Army of the Potomac's II, V, and VI Corps, which had been brought from the Peninsula and—much to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's dismay—placed under Pope's command.

By the morning of August 31, Pope began to lose his grasp on command of his army. The defeat at Second Bull Run seemed to have shattered his nerve and Pope was unsure what to do next; he knew Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

wanted an attack but he feared Lee might strike first and destroy his reforming force before it was ready to fight again. Calling a conference of his corps commanders—something he had been loath to do previously in the Virginia Campaign—in his Centreville headquarters, Pope agreed with their decision to retreat further into the Washington defenses. But a message from General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

directed him to attack and he ordered an advance on Lee's forces on the Manassas field.

Lee, however, had already set in motion his own plan that would rob Pope of the initiative to attack. Lee directed Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson to march his troops around Pope's right flank to get behind the Union position at Centreville. Leading the way and scouting for any Union blocking force was Confederate cavalry under the command of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials o ...

. Maj. Gen. James Longstreet's command would remain in place for the day to deceive Pope into believing that Lee's entire force remained in his front, while Jackson's command made its flanking march, north and then east, to take strategically important Germantown, Virginia

Germantown is a historic unincorporated rural community in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States. It is the resting place of John Jacob Richter (also spelled Rector). He was buried there in 1729. It is located in and around current-day C. ...

, where Pope's only two routes to Washington—the Warrenton Pike (modern U.S. Route 29) and the Little River Turnpike (modern U.S. Route 50)—converged. Jackson's men, hungry and worn, moved slowly and bivouacked for the night at Pleasant Valley, three miles northeast of Centreville. As Pope settled down for the night on August 31, he was unaware that Jackson was on the verge of turning his flank.

During the night two events occurred that forced Pope to change his mind. A staff officer arrived from the Germantown position to report that a heavy force of cavalry had shelled the intersection before retreating. Pope initially dismissed the cavalry as little more than a patrol. But when, hours later, two Union cavalrymen reported seeing a large mass of infantry marching east down the Little River Turnpike, Pope realized that his army was in danger. He countermanded actions preparing for an attack and directed the army to retreat from Centreville to Washington; he also sent out a series of infantry probes up the roads that Lee might use to reach his troops as they pulled back.

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

On the morning of September 1, Pope ordered Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner of the

On the morning of September 1, Pope ordered Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner of the II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

, Army of the Potomac, to send a brigade north to reconnoiter; the army's cavalry was too exhausted for the mission. But at the same time, he continued his movement in the direction of Washington, sending McDowell's corps to Germantown (on the western border of modern-day Fairfax, Virginia), where it could protect the important intersection of Warrenton Pike and Little River Turnpike that the army needed for the retreat. He also sent two brigades from Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno

Jesse Lee Reno (April 20, 1823 – September 14, 1862) was a career United States Army officer who served in the Mexican–American War, in the Utah War, on the western frontier and as a Union General during the American Civil War from West Vir ...

's IX Corps, under the command of Brig. Gen. Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

, to block Jackson. Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny

Philip Kearny Jr. (; June 1, 1815 – September 1, 1862) was a United States Army officer, notable for his leadership in the Mexican–American War and American Civil War. He was killed in action in the 1862 Battle of Chantilly.

Early life and ...

's division from the III Corps followed later that afternoon.

Jackson resumed his march to the south, but his troops were tired and hungry and made poor progress as the rain continued. They marched only three miles and occupied Ox Hill, southeast of Chantilly Plantation, and halted, while Jackson himself took a nap. All during the morning, Confederate cavalry skirmished with Union infantry and cavalry. At about 3 p.m., Stevens' division arrived at Ox Hill. Despite being outnumbered, Stevens chose to attack across a grassy field against Brig. Gen. Alexander Lawton

Alexander Robert Lawton (November 4, 1818 – July 2, 1896) was a lawyer, politician, diplomat, and brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Lawton was born in the Beaufort District of South ...

's division in the Confederate center. The Union attack was initially successful, routing the brigade of Colonel Henry Strong and driving in the flank of Captain William Brown, with Brown killed during the fighting. The Union division was driven back following a counterattack by Brig. Gen. Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his U.S. Army commiss ...

's brigade. Stevens was killed during this attack about 5 p.m. by a shot through his temple.

A severe thunderstorm erupted about this time, resulting in limited visibility and an increased dependence on the bayonet, as the rain soaked the ammunition of the infantry and made it useless. Kearny arrived about this time with his division to find Stevens' units disorganized. Perceiving a gap in the line he deployed Brig. Gen.

A severe thunderstorm erupted about this time, resulting in limited visibility and an increased dependence on the bayonet, as the rain soaked the ammunition of the infantry and made it useless. Kearny arrived about this time with his division to find Stevens' units disorganized. Perceiving a gap in the line he deployed Brig. Gen. David B. Birney

David Bell Birney (May 29, 1825 – October 18, 1864) was a businessman, lawyer, and a Union general in the American Civil War.

Early life

Birney was born in Huntsville, Alabama, the son of an abolitionist from Kentucky, James G. Birney. The Bi ...

's brigade on Stevens's left, ordering it to attack across the field. Birney managed to maneuver close to the Confederate line but his attack stalled in hand-to-hand combat with Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill

Ambrose Powell Hill Jr. (November 9, 1825April 2, 1865) was a Confederate general who was killed in the American Civil War. He is usually referred to as A. P. Hill to differentiate him from another, unrelated Confederate general, Daniel Harvey H ...

's division. Kearny mistakenly rode into the Confederate lines during the battle and was killed. As Kearny's other two brigades arrived on the field, Birney used the reinforcements as a rear guard as he withdrew the remainder of the Union force to the southern side of the farm fields, ending the battle.

Aftermath

That night, Longstreet arrived to relieve Jackson's troops and to renew the battle in the morning. The lines were so close that some soldiers accidentally stumbled into the camps of the opposing army. The Union army withdrew to Germantown and Fairfax Court House that night, followed over the next few days by retreating to the defenses of Washington. The Confederate cavalry attempted a pursuit but failed to cause significant damage to the Union army. The fighting was tactically inconclusive. Although Jackson's turning movement was foiled and he was unable to block the Union retreat or destroy Pope's army, National Park Service historians count Chantilly as a strategic Confederate victory because it neutralized any threat from Pope's army and cleared the way for Lee to begin his Maryland Campaign. The Confederates claimed a tactical victory as well because they held the field after the battle. Two Union generals were killed, while one Confederate brigade commander was killed. Pope, recognizing the attack as an indication of continued danger to his army, continued his retreat to the fortifications aroundWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

Lee began the Maryland Campaign, which culminated in the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

, after Pope retreated from Virginia. The Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, absorbed the forces of Pope's Army of Virginia, which was disbanded as a separate army.

Battlefield today

The site of the battle, once rural farmland, is now surrounded by suburban development in Fairfax County. The modern thoroughfares of U.S. Route 50 (Lee-Jackson Memorial Highway) and State Route 286 (Fairfax County Parkway), as well as State Route 608 (West Ox Road) intersect near the location of the battle. A 4.8 acre (19,000 m²) memorial park, the Ox Hill Battlefield Park, is located off of West Ox Road and lies adjacent to the Fairfax Towne Center shopping area, and includes most of the Gen. Isaac Stevens portion of the battle, about 1.5% of the total ground. The park is under the jurisdiction of theFairfax County Park Authority The Fairfax County Park Authority is a department of the Fairfax County, Virginia county government responsible for developing and maintaining the various parks, historical sites, and recreational areas owned or administered by Fairfax County. Figu ...

; in January 2005, the Authority approved a General Management Plan and Conceptual Development Plan that sets forth a detailed history and future management framework for the site.

A small yard located within the nearby Fairfax Towne Center has been preserved to mark the area crossed by Confederate troops to get to the Ox Hill battlefield.Taylor, p. 128.

Notes

References

* Esposito, Vincent J. ''West Point Atlas of American Wars''. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. . A copy is available online at thLibrary of Congress

* Hennessy, John J. ''Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. . * Ropes, John Codman. ''The Army in the Civil War''. Vol. 4, ''The Army under Pope''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1881. . * Salmon, John S. ''The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. . * Taylor, Paul. ''He Hath Loosed the Fateful Lightning: The Battle of Ox Hill (Chantilly), September 1, 1862''. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishers, 2003. .

CWSAC Report Update

* Welker, David A. "Tempest at Ox Hill: The Battle of Chantilly." New York: DaCapo, 2002. .

Further reading

* Mauro, Charles V. ''The Battle of Chantilly (Ox Hill): A Monumental Storm''. Fairfax, VA: Fairfax County History Commission, 2002. . * Welker, David. ''Tempest at Ox Hill: The Battle of Chantilly''. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002. .External links

Animated maps, histories, photos, and preservation news. (

Civil War Trust

The American Battlefield Trust is a charitable organization (501(c)(3)) whose primary focus is in the preservation of battlefields of the American Civil War, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 through acquisition of battlefield land. The ...

)

''The Battle of Chantilly (Ox Hill)'', a docudrama about the battle

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chantilly

Chantilly

Chantilly may refer to:

Places

France

*Chantilly, Oise, a city located in the Oise department

**US Chantilly, a football club

*Château de Chantilly, a historic château located in the town of Chantilly

United States

* Chantilly, Missou ...

Chantilly

Chantilly may refer to:

Places

France

*Chantilly, Oise, a city located in the Oise department

**US Chantilly, a football club

*Château de Chantilly, a historic château located in the town of Chantilly

United States

* Chantilly, Missou ...

Chantilly

Chantilly may refer to:

Places

France

*Chantilly, Oise, a city located in the Oise department

**US Chantilly, a football club

*Château de Chantilly, a historic château located in the town of Chantilly

United States

* Chantilly, Missou ...

Chantilly

Chantilly may refer to:

Places

France

*Chantilly, Oise, a city located in the Oise department

**US Chantilly, a football club

*Château de Chantilly, a historic château located in the town of Chantilly

United States

* Chantilly, Missou ...

Chantilly

Chantilly may refer to:

Places

France

*Chantilly, Oise, a city located in the Oise department

**US Chantilly, a football club

*Château de Chantilly, a historic château located in the town of Chantilly

United States

* Chantilly, Missou ...

1862 in Virginia

1862 in the American Civil War

September 1862 events