Battle Of Spencer's Ordinary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

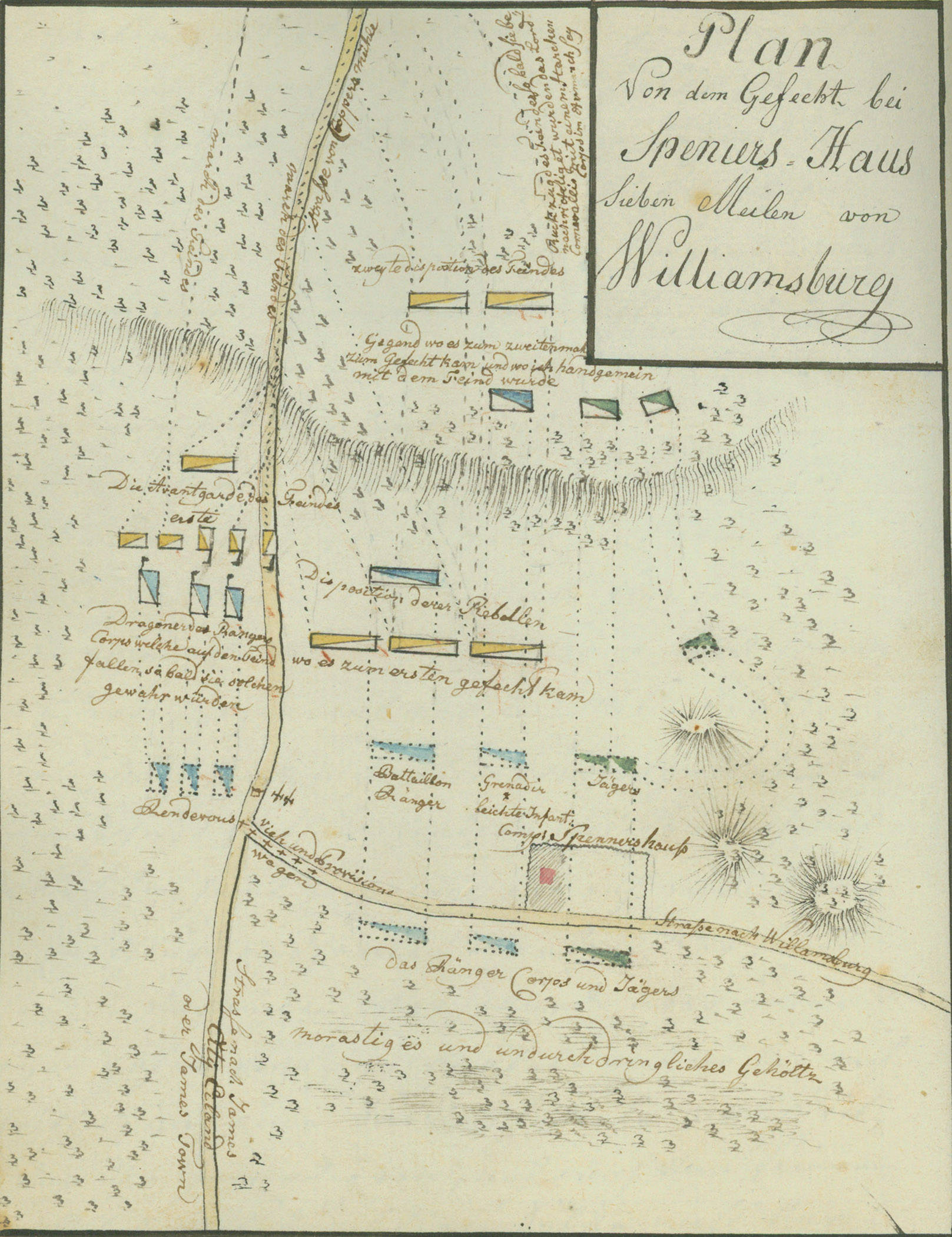

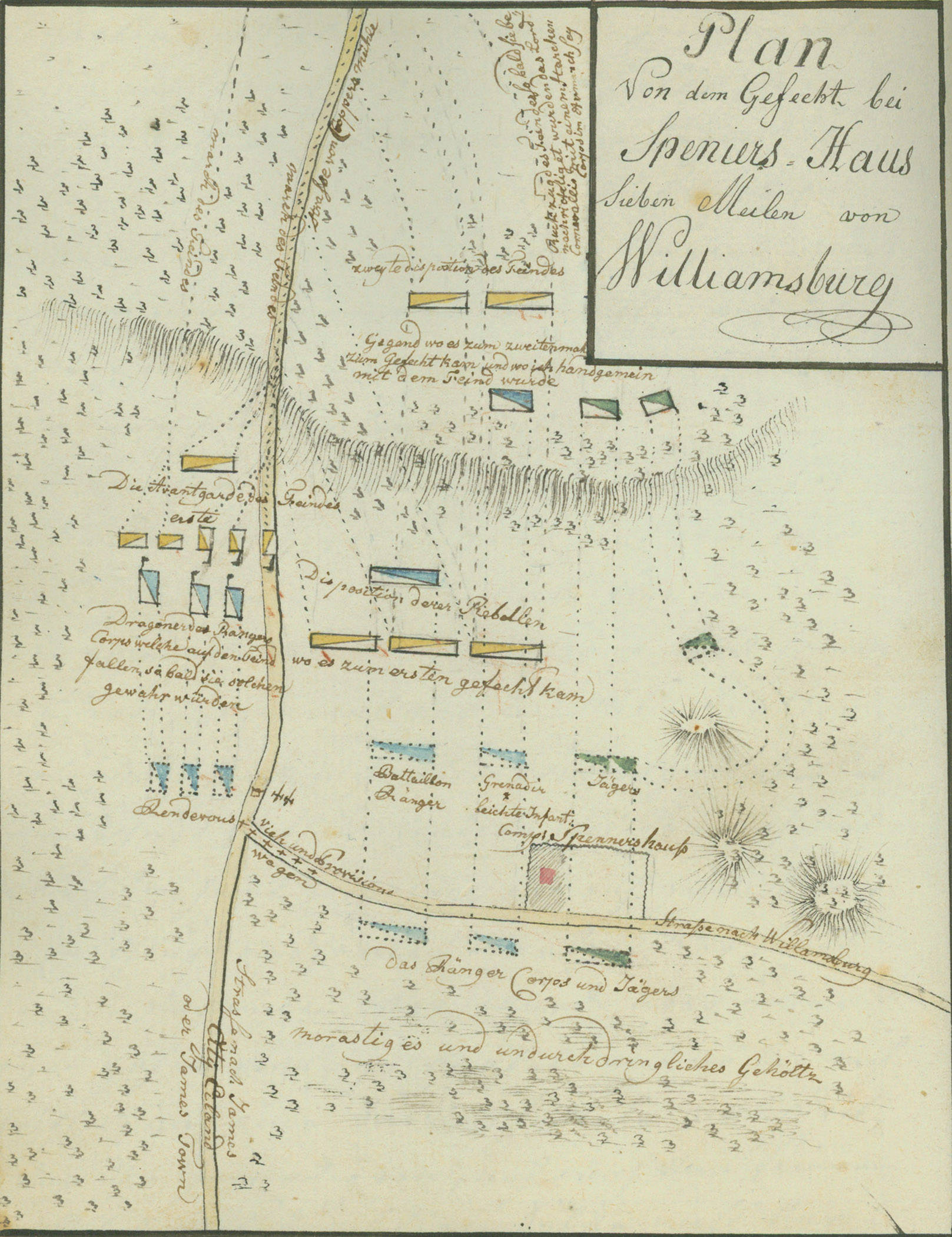

The Battle of Spencer's Ordinary was an inconclusive

Lafayette, once he was joined by Wayne and Campbell, wanted to engage elements of Cornwallis' army without necessarily facing its full strength. As Cornwallis approached Williamsburg, Lafayette and Wayne received word that Lieutenant Colonel

Lafayette, once he was joined by Wayne and Campbell, wanted to engage elements of Cornwallis' army without necessarily facing its full strength. As Cornwallis approached Williamsburg, Lafayette and Wayne received word that Lieutenant Colonel

Simcoe's troops were moving down the road toward Williamsburg, convoying some cattle with the infantry and jägers in the lead under Major Richard Armstrong, with Simcoe and the cavalry about an hour behind them. At Spencer's Ordinary (" ordinary" meaning

Simcoe's troops were moving down the road toward Williamsburg, convoying some cattle with the infantry and jägers in the lead under Major Richard Armstrong, with Simcoe and the cavalry about an hour behind them. At Spencer's Ordinary (" ordinary" meaning

skirmish

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an ir ...

that took place on 26 June 1781, late in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

forces under Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the Drainage basin, watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. ...

and American forces under Colonel Richard Butler, light detachments from the armies of General Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

and the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revoluti ...

respectively, clashed near a tavern (the " ordinary") at a road intersection not far from Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula ...

.

Lafayette had been shadowing Cornwallis as he moved his army toward Williamsburg from central Virginia. Aware that Simcoe had become separated from Cornwallis, he sent Butler out in an attempt to cut Simcoe off. Both sides, concerned that the other might be reinforced by its main army, eventually broke off the battle.

Background

In May 1781, LordCharles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

arrived in Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines Petersburg (along with the city of Colonial Heights) with Din ...

after a lengthy campaign through North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. In addition to his 1,400 troops, he assumed command of another 3,600 troops that had been under the command of the turncoat Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

, and was soon thereafter further reinforced by about 2,000 more troops sent from New York. These forces were opposed by a much smaller Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

force led by the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revoluti ...

, then located at Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

. Following orders originally given to Arnold's predecessor in command, William Phillips William Phillips may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Phillips (editor) (1907–2002), American editor and co-founder of ''Partisan Review''

* William T. Phillips (1863–1937), American author

* William Phillips (director), Canadian film-make ...

(who died a week before Cornwallis' arrival), Cornwallis worked to eliminate Virginia's ability to support the revolutionary cause, and gave chase to Lafayette's army, which numbered barely 3,000 and included a large number of inexperienced militia.

Lafayette successfully eluded engaging Cornwallis for about one month, who used his numerical advantage to detach forces for raids against economic, military, and political targets in central Virginia. Cornwallis then turned back to the east, marching for Williamsburg. Lafayette, whose force grew to number about 4,000 with the arrival of Continental Army reinforcements under General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

and additional experienced militiamen under William Campbell, followed Cornwallis. Buoyed by the increase in his troop strength, Lafayette also became more aggressive in his tactics, sending out detachments of his force to counteract those that Cornwallis sent on forage and raiding expeditions.Wickwire, p. 335 These detachments were composed of select units taken from a variety of regiments. Among those that were commonly in the army's advance guard were a combined cavalry and infantry unit from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

under Captain William McPherson, and companies of Virginia riflemen under Majors Richard Call and John Willis.

Lafayette, once he was joined by Wayne and Campbell, wanted to engage elements of Cornwallis' army without necessarily facing its full strength. As Cornwallis approached Williamsburg, Lafayette and Wayne received word that Lieutenant Colonel

Lafayette, once he was joined by Wayne and Campbell, wanted to engage elements of Cornwallis' army without necessarily facing its full strength. As Cornwallis approached Williamsburg, Lafayette and Wayne received word that Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the Drainage basin, watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. ...

and his Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

regiment of Queen's Rangers

The Queen's Rangers, also known as the Queen's American Rangers, and later Simcoe's Rangers, were a Loyalist military unit of the American Revolutionary War. Formed in 1776, they were named for Queen Charlotte, consort of George III. The Queen' ...

were returning from a raid to destroy boats and forage for supplies on the Chickahominy River

The Chickahominy is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 river in the eastern portion of the U.S. state of Virginia. The river, which serves as the eastern bo ...

.Johnston, p. 55 Simcoe's full force included, in addition to the Rangers, a few companies of Hessian

A Hessian is an inhabitant of the German state of Hesse.

Hessian may also refer to:

Named from the toponym

*Hessian (soldier), eighteenth-century German regiments in service with the British Empire

**Hessian (boot), a style of boot

**Hessian f ...

jägers led by Captains Johann Ewald

Johann von Ewald (20 March 1744 – 25 June 1813) was a German military officer from Hesse-Kassel. After first serving in the Seven Years' War, he was the commander of the Jäger corps of the Hessian Leib Infantry Regiment attached to British f ...

and Johann Althaus.Fryer and Dracott, p. 66 On the night of 25 June, Wayne sent most of the advance guard under Colonel Richard Butler, including McPherson, Call, and Willis, to intercept Simcoe's force. A forward party of about 50 dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s and 50 light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought ...

under McPherson caught up with advance companies of Simcoe's force near Spencer's Ordinary, a tavern at a road intersection about north of Williamsburg.Johnston, p. 56

Battle

Simcoe's troops were moving down the road toward Williamsburg, convoying some cattle with the infantry and jägers in the lead under Major Richard Armstrong, with Simcoe and the cavalry about an hour behind them. At Spencer's Ordinary (" ordinary" meaning

Simcoe's troops were moving down the road toward Williamsburg, convoying some cattle with the infantry and jägers in the lead under Major Richard Armstrong, with Simcoe and the cavalry about an hour behind them. At Spencer's Ordinary (" ordinary" meaning tavern

A tavern is a place of business where people gather to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food such as different types of roast meats and cheese, and (mostly historically) where travelers would receive lodging. An inn is a tavern that h ...

at the time), the troops rejoined and paused to rest. Simcoe ordered fences in the area torn down since "it was an admirable place for the chicanery of action". While they rested, some of the Loyalists went out to round up more cattle found in the area, and the cavalry went to a nearby farm to feed their horses. McPherson's men encountered the latter, whose sentries raised the alarm to the main body. Simcoe's cavalry charged McPherson's formation, breaking it up. McPherson and a number of his men were unhorsed in the melee, and several were taken prisoner before the leading edge of Butler's main force began to arrive. Simcoe ordered most of the infantry up to support his cavalry, and sent the jägers and light infantry into the woods on the right to flank the arriving enemy column.Fryer and Dracott, p. 67 By questioning the prisoners, Simcoe learned that Lafayette was not far off. He sent word to Cornwallis, dispatched the cattle convoy toward Williamsburg, and ordered trees to be felled to make a barricade across the road as a point of defense. He then arrayed his troops in a way calculated to mislead the Americans into believing that more troops were in formation just over a rise. When Butler's force arrived, Simcoe ordered an infantry charge. This scattered the first wave of Butler's men into the nearby woods, where the jägers then pushed them back. However, Butler's men continued to advance. Simcoe ordered a cavalry charge and fired a field cannon to give the impression that a larger force was arriving. The charge forced Butler's men back, at which point the two forces disengaged, Simcoe because he was concerned that Lafayette was approaching, and Butler because his men were fooled by Simcoe's stratagem.Fryer and Dracott, p. 69Lossing, p. 259

Aftermath

Simcoe left his wounded men at the tavern under a truce flag, and withdrew down the Williamsburg road, joining with forces Cornwallis sent about two miles (3.2 km) down the road.Fryer and Dracott, p. 70 The Americans retreated to Lafayette's camp at Tyre's Plantation, and Simcoe was able to return to the tavern and recover his wounded. Simcoe reported his losses at 11 killed and 25 wounded, and the American loss at 9 killed, 14 wounded, and 32 captured. Lafayette claimed the Americans had killed 60 and wounded 100, while Cornwallis claimed the British had 33 killed and wounded. (The latter number agrees with that provided by Fryer and Dracott if Hessian casualties are excluded.) The location of the battle is now within the grounds ofJames City County

James City County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 78,254. Although politically separate from the county, the county seat is the adjacent independent city of Williamsburg.

Located ...

's Freedom Park in Williamsburg. Published park materials do not indicate if the exact location is marked in any way.

Butler's identity

Sources disagree on the name of the Butler who commanded the American force. In early histories,Benson Lossing

Benson John Lossing (February 12, 1813 – June 3, 1891) was a prolific and popular American historian, known best for his illustrated books on the American Revolution and American Civil War and features in ''Harper's Magazine''. He was a c ...

claims that one Percival Butler was in command, who had also served under Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan (1735–1736July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. One of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783, he later commanded troops during the sup ...

in earlier campaigns, while Henry Johnston identifies the commander as Richard Butler, a hero of Stony Point. In modern histories, Fryer and Dracott also identify him as Richard, while Brendan Morrissey apparently misidentifies him as John Butler John Butler may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*John "Picayune" Butler (died 1864), American performer

*John Butler (artist) (1890–1976), American artist

* John Butler (author) (born 1937), British author and YouTuber

*John Butler (born 1954), ...

.Morrissey, p. 25

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Spencers OrdinaryBattle of Spencer's Ordinary

The Battle of Spencer's Ordinary was an inconclusive skirmish that took place on 26 June 1781, late in the American Revolutionary War. British forces under Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe and American forces under Colonel Richard Butler, ...

Spencer's Ordinary

Spencer's Ordinary

Spencer's Ordinary

Spencer's Ordinary

James City County, Virginia

1781 in Virginia