Bantustans In South Africa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Bantustan (also known as

A Bantustan (also known as

Bantustan

, "1. one of the areas in South Africa where black people lived during the apartheid system; 2. SHOWING DISAPPROVAL any area where people are forced to live without full civil and political rights." The term, first used in the late 1940s, was coined from

Bantu

' (meaning "people" in some of the

Beginning in 1913, successive white-minority South African governments established "reserves" for the black population in order to racially segregate them from the white population. The

Beginning in 1913, successive white-minority South African governments established "reserves" for the black population in order to racially segregate them from the white population. The

The homelands are listed below with the ethnic group for which each homeland was designated. Four were nominally independent (the so-called TBVC states of the

The homelands are listed below with the ethnic group for which each homeland was designated. Four were nominally independent (the so-called TBVC states of the

In the 1960s

In the 1960s

Bantustan policyEncyclopædia Britannica, Bantustan

*

Divide & Rule: South Africa's Bantustans

' by Barbara Rogers (1980) * Pelliccioni Franco, LO SVILUPPO DELLE "BANTU HOMELANDS" NEL SUDAFRICA, 197

(1974) {{Authority control Lands reserved for indigenous peoples South African English Political terminology in South Africa 1994 disestablishments in South Africa

Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for National ...

homeland, black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

homeland, black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

state or simply homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

(now Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

), as part of its policy of apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

. By extension, outside South Africa the term refers to regions that lack any real legitimacy, consisting often of several unconnected enclaves, or which have emerged from national or international gerrymandering

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

.Macmillan DictionaryBantustan

, "1. one of the areas in South Africa where black people lived during the apartheid system; 2. SHOWING DISAPPROVAL any area where people are forced to live without full civil and political rights." The term, first used in the late 1940s, was coined from

Bantu

' (meaning "people" in some of the

Bantu languages

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀) are a large family of languages spoken by the Bantu people of Central, Southern, Eastern africa and Southeast Africa. They form the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages.

The t ...

) and ''-stan

The suffix -stan ( fa, ـستان, translit=''stân'' after a vowel; ''estân'' or ''istân'' after a consonant), has the meaning of "a place abounding in" or "a place where anything abounds" in the Persian language. It appears in the names of ...

'' (a suffix meaning "land" in the Persian language

Persian (), also known by its endonym Farsi (, ', ), is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken and ...

and some Persian-influenced languages of western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

, central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

, and southern Asia). It subsequently came to be regarded as a disparaging term by some critics of the apartheid-era government's ''homelands''. The Pretoria government established ten Bantustans in South Africa, and ten in neighbouring South West Africa (then under South African administration), for the purpose of concentrating the members of designated ethnic groups, thus making each of those territories ethnically homogeneous as the basis for creating autonomous nation states for South Africa's different black ethnic groups. Under the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act

The Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, 1970 (Act No. 26 of 1970; subsequently renamed the Black States Citizenship Act, 1970 and the National States Citizenship Act, 1970) was a Self Determination or denaturalization law passed during the aparthei ...

of 1970, the government stripped black South Africans of their South African citizenship, depriving them of their few remaining political and civil rights in South Africa, and declared them to be citizens of these homelands.

The government of South Africa declared as independent four of the South African Bantustans—Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

, Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

, Venda

Venda () was a Bantustan in northern South Africa, which is fairly close to the South African border with Zimbabwe to the north, while to the south and east, it shared a long border with another black homeland, Gazankulu. It is now part of the ...

, and Ciskei

Ciskei (, or ) was a Bantustan for the Xhosa people-located in the southeast of South Africa. It covered an area of , almost entirely surrounded by what was then the Cape Province, and possessed a small coastline along the shore of the Indian O ...

(the so-called "TBVC States"), but this declaration was never recognised by anti-apartheid forces in South Africa or by any international government. Other Bantustans (like KwaZulu

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

It was led until its abolition in 1994 by Chief Mangosuth ...

, Lebowa

Lebowa was a bantustan ("homeland") located in the Transvaal in northeastern South Africa. Seshego initially acted as Lebowa's capital while the purpose-built Lebowakgomo was being constructed. Granted internal self-government on 2 October ...

, and QwaQwa

QwaQwa was a bantustan ("homeland") in the central eastern part of South Africa. It encompassed a very small region of in the east of the former South African province of Orange Free State, bordering Lesotho. Its capital was Phuthaditjhaba. It ...

) were assigned "autonomy" but never granted "independence". In South West Africa, Ovamboland

Ovamboland, also referred to as Owamboland, was a Bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Ovambo people.

The term originally referred to the parts ...

, Kavangoland

Kavangoland was a bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Kavango people. It was set up in 1970 and self-government was granted in 1973. The Kavango L ...

, and East Caprivi

East Caprivi or Itenge was a bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Masubiya people. It was set up in 1972, in the very corner of the Namibian panhan ...

were declared to be self-governing, with a handful of other ostensible homelands never being given autonomy. A new constitution effectively abolished the Bantustans with the end of apartheid in South Africa in 1994.

Creation

Beginning in 1913, successive white-minority South African governments established "reserves" for the black population in order to racially segregate them from the white population. The

Beginning in 1913, successive white-minority South African governments established "reserves" for the black population in order to racially segregate them from the white population. The Natives Land Act, 1913

The Natives Land Act, 1913 (subsequently renamed Bantu Land Act, 1913 and Black Land Act, 1913; Act No. 27 of 1913) was an Act of the Parliament of South Africa that was aimed at regulating the acquisition of land.

According to the ''Encyclopæd ...

, limited blacks to seven percent of the land in the country. In 1936 the government planned to raise this to 13.6 percent of the land, but it was slow to purchase land and this plan was not fully implemented.

When the National Party came to power in 1948, Minister for Native Affairs (and later Prime Minister of South Africa

The prime minister of South Africa ( af, Eerste Minister van Suid-Afrika) was the head of government in South Africa between 1910 and 1984.

History of the office

The position of Prime Minister was established in 1910, when the Union of Sout ...

) Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of '' Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

built on this, introducing a series of "grand apartheid" measures such as the Group Areas Act

Group Areas Act was the title of three acts of the Parliament of South Africa enacted under the apartheid government of South Africa. The acts assigned racial groups to different residential and business sections in urban areas in a system of u ...

s and the Natives Resettlement Act, 1954

The Natives Resettlement Act, Act No 19 of 1954, formed part of the apartheid system of racial segregation in South Africa. It permitted the removal of blacks from any area within and next to the magisterial district of Johannesburg by the South ...

that reshaped South African society such that whites would be the demographic majority. The creation of the homelands or Bantustans was a central element of this strategy, as the long-term goal was to make the Bantustans independent. As a result, blacks would lose their South African citizenship and voting rights, allowing whites to remain in control of South Africa.

The term "Bantustan" for the Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for National ...

homelands was intended to draw a parallel with the creation of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

("Hindustan

''Hindūstān'' ( , from '' Hindū'' and ''-stān''), also sometimes spelt as Hindōstān ( ''Indo-land''), along with its shortened form ''Hind'' (), is the Persian-language name for the Indian subcontinent that later became commonly used by ...

"), which had taken place just a few months before at the end of 1947, and was coined by supporters of the policy. However, it quickly became a pejorative term, with the National Party preferring the term "homelands". As Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

explained in a 1959 article:

The newspapers have christened the Nationalists' plan as one for "Bantustans". The hybrid word is, in many ways, extremely misleading. It relates to the partitioning of India, after the reluctant departure of the British, and as a condition thereof, into two separate States, Hindustan and Pakistan. There is no real parallel with the Nationalists' proposals, for (a) India and Pakistan constitute two completely separate and politically independent States, (b)"While apartheid was an ideology born of the will to survive or, put differently, the fear of extinction, Afrikaner leaders differed on how best to implement it. While some were satisfied with segregationist policies placing them at the top of a social and economic hierarchy, others truly believed in the concept of 'separate but equal'. For the latter, the ideological justification for the classification, segregation, and denial of political rights was the plan to set aside special land reserves for black South Africans, later called 'bantustans' or 'homelands'. Each ethnic group would have its own state with its own political system and economy, and each would rely on its own labour force. These independent states would then coexist alongside white South Africa in a spirit of friendship and collaboration. In their own areas, black citizens would enjoy full rights." Verwoerd argued that the Bantustans were the "original homes" of the black peoples of South Africa. In 1951, the government ofMuslims Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...enjoy equal rights in India;Hindus Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...enjoy equal rights in Pakistan, (c) Partition was submitted to and approved by both parties, or at any rate fairly widespread and Influential sections of each. The Government's plans do not envisage the partitioning of this country into separate, self-governing States. They do not envisage equal rights, or any rights at all, for Africans outside the reserves. Partition has never been approved of by Africans and never will be. For that matter it has never been really submitted to or approved of by the Whites. The term "Bantustan" is therefore a complete misnomer, and merely tends to help the Nationalists perpetrate a fraud.

Daniel François Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

introduced the Bantu Authorities Act to establish "homelands" allocated to the country's black ethnic groups. These amounted to 13% of the country's land, the remainder being reserved for the white population. The homelands were run by cooperative tribal leaders, while uncooperative chiefs were forcibly deposed. Over time, a ruling black elite emerged with a personal and financial interest in the preservation of the homelands. While this aided the homelands' political stability to an extent, their position was still entirely dependent on South African support.

The role of the homelands was expanded in 1959 with the passage of the Bantu Self-Government Act

The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act, 1959 (Act No. 46 of 1959, commenced 19 June; subsequently renamed the Promotion of Black Self-government Act, 1959 and later the Representation between the Republic of South Africa and Self-governing T ...

, which set out a plan called "Separate Development

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

". This enabled the homelands to establish themselves in the long term as self-governing territories and ultimately as nominally fully "independent" states.

This process was to be achieved in a series of four major steps for each homeland:

* The unification of the reserves set aside for the various "tribes" (officially called "nations" since 1959) under a single "Territorial Authority"

* The establishment of a legislative assembly for each homeland with limited powers of self-rule

* The establishment of the homeland as a "self-governing territory"

* The granting of full nominal independence to the homeland

This general framework was not in each case followed in a clear-cut way, but often with a number of intermediate and overlapping steps.

The homeland of Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

served in many regards as a "testing ground" for apartheid policies; its institutional development started already before the 1959 act, and its attainment of self-government and independence were therefore implemented earlier than for the other homelands.

This plan was stepped up under Verwoerd's successor as prime minister, John Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

, as part of his "enlightened" approach to apartheid. However, the true intention of this policy was to fulfill Verwoerd's original plan to make South Africa's blacks nationals of the homelands rather than of South Africa—thus removing the few rights they still had as citizens. The homelands were encouraged to opt for independence, as this would greatly reduce the number of black citizens of South Africa. The process of creating the legal framework for this plan was completed by the Black Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970, which formally designated all black South Africans as citizens of the homelands, even if they lived in "white South Africa", and cancelled their South African citizenship, and the Bantu Homelands Constitution Act of 1971, which provided a general blueprint for the stages of constitutional development of all homelands (except Transkei) from the establishment of Territorial Authorities up to full independence.

By 1984, all ten homelands in South Africa had attained self-government and four of them (Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

, Boputhatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

, Venda

Venda () was a Bantustan in northern South Africa, which is fairly close to the South African border with Zimbabwe to the north, while to the south and east, it shared a long border with another black homeland, Gazankulu. It is now part of the ...

and Ciskei

Ciskei (, or ) was a Bantustan for the Xhosa people-located in the southeast of South Africa. It covered an area of , almost entirely surrounded by what was then the Cape Province, and possessed a small coastline along the shore of the Indian O ...

) had been declared fully independent between 1976 and 1981.

The following table shows the time-frame of the institutional and legal development of the ten South African Bantustans in light of the above-mentioned four major steps:

In parallel with the creation of the homelands, South Africa's black population was subjected to a massive programme of forced relocation. It has been estimated that 3.5 million people were forced from their homes from the 1960s through the 1980s, many being resettled in the Bantustans.

The government made clear that its ultimate aim was the total removal of the black population from South Africa. Connie Mulder

Connie Mulder, born Cornelius Petrus Mulder (5 June 1925– 12 January 1988), was a South African politician, cabinet minister and father of Pieter Mulder, former leader of the Freedom Front Plus.

He started his career as a teacher of Afri ...

, the Minister of Plural Relations and Development, told the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies as the colony gained more internal responsible governme ...

on 7 February 1978:

But this goal was not achieved. Only a minority (about 39% in 1986) of South Africa's black population lived in the Bantustans; the remainder lived in South Africa proper, many in township

A township is a kind of human settlement or administrative subdivision, with its meaning varying in different countries.

Although the term is occasionally associated with an urban area, that tends to be an exception to the rule. In Australia, Ca ...

s, shanty-towns and slums on the outskirts of South African cities.

International recognition

Bantustans within the borders of South Africa were classified as "self-governing" or "independent". In theory, self-governing Bantustans had control over many aspects of their internal functioning but were not yet sovereign nations. Independent Bantustans (Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei; also known as the TBVC states) were intended to be fully sovereign. These areas received little attention from the colonial and later South African governments however, and were still very undeveloped. This greatly decreased these states' ability to govern and made them very reliant on the South African government. Throughout the existence of the independent Bantustans, South Africa remained the only country to recognise their independence. The South African government lobbied for their recognition. In 1976, leading up to aUnited States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

resolution urging the President not to recognise Transkei, the South African government intensely lobbied lawmakers to oppose the bill. Arbitrary and unrecognized amateur radio call signs

Amateur radio call signs are allocated to amateur radio operators around the world. The call signs are used to legally identify the station or operator, with some countries requiring the station call sign to always be used and others allowing the ...

were created for the independent states and QSL cards were sent by operators using them, but the International Telecommunication Union

The International Telecommunication Union is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information and communication technologies. It was established on 17 May 1865 as the International Telegraph Unio ...

never accepted these stations as legitimate. Each TBVC state extended recognition to the other independent Bantustans while South Africa showed its commitment to the notion of TBVC sovereignty by building embassies in the TBVC capitals.

Life in the Bantustans

The Bantustans were generally poor, with few local employment opportunities. However, some opportunities did exist for advancement for blacks and some advances in education and infrastructure were made. The four Bantustans which attained nominal independence (Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei), repealed all Apartheid legislation upon independence. Laws in the Bantustans differed from those in South Africa proper. The South African elite often took advantage of these differences, for example by constructing largecasino

A casino is a facility for certain types of gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shopping, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos are also known for hosting live entertai ...

s, such as Sun City in the homeland of Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

.

Bophuthatswana also possessed deposits of platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Platinu ...

, and other natural resources, which made it the wealthiest of the Bantustans.

However, the homelands were only kept afloat by massive subsidies from the South African government; for instance, by 1985 in Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

, 85% of the homeland's income came from direct transfer payments from Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

. The Bantustans' governments were invariably corrupt and little wealth trickled down to the local populations, who were forced to seek employment as "guest workers" in South Africa proper. Millions of people had to work in often appalling conditions, away from their homes for months at a time. On the other hand, only 40% of Bophuthatswana's population worked outside the 'homeland' because the homeland was able to create industrial sites like Zone 15 and Babelegi.

The homelands were extremely unpopular among the urban black population, many of whom lived in squalor in slum housing

A slum is a highly populated urban residential area consisting of densely packed housing units of weak build quality and often associated with poverty. The infrastructure in slums is often deteriorated or incomplete, and they are primarily in ...

. Their working conditions were often equally poor, as they were denied any significant rights or protections in South Africa proper. The allocation of individuals to specific homelands was often quite arbitrary. Many individuals assigned to homelands did not live in or originate from the homelands to which they were assigned, and the division into designated ethnic groups often took place on an arbitrary basis, particularly in the case of people of mixed ethnic ancestry.

Bantustan leaders were widely perceived as collaborators with the apartheid system, although some were successful in acquiring a following. Most homeland leaders had an ambivalent stance regarding the independence of their homelands: a majority was sceptical, remained cautious and avoided a definite decision, some outright rejected it due to their rejection of "separate development" and a professed commitment to "opposing apartheid from within the system", whilst others believed that nominal independence could serve to consolidate their power bases (to an even higher degree than the, in fact, already quite powerful status they enjoyed as rulers of self-governing homelands) and presented an opportunity to build a society relatively free from racial discrimination. In general, the leaders of the Bantustans, despite their overall collaboration and often collusion with the apartheid regime, did not shy away from occasionally attacking the South African government's racial policies and calling for the repeal or softening of apartheid laws (most of which were repealed in nominally independent states). Various plans for a federal solution were at times mooted, both by the Bantustan governments and by opposition parties in South Africa as well as circles inside the white ruling National Party.

Later developments

In January 1985, State PresidentP. W. Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, (; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006), commonly known as P. W. and af, Die Groot Krokodil (The Big Crocodile), was a South African politician. He served as the last prime minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 and ...

declared that blacks in South Africa proper would no longer be deprived of South African citizenship

South African nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of South Africa. The primary law governing nationality requirements is the South African Citizenship Act, 1995, which came into force on 6 October 1995.

Any p ...

in favour of Bantustan citizenship and that black citizens within the independent Bantustans could reapply for South African citizenship; F. W. de Klerk stated on behalf of the National Party during the 1987 general election that "every effort to turn the tide f black workers

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

streaming into the urban areas failed. It does not help to bluff ourselves about this. The economy demands the permanent presence of the majority of blacks in urban areas ... They cannot stay in South Africa year after year without political representation." In March 1990, de Klerk, who succeeded Botha as State President in 1989, announced that his government would not grant independence to any more Bantustans.

These remarks were however by no means meant as a rejection of the Bantustan system in general: the goal of the apartheid regime during the second half of the 1980s was to "modernize" the organisational framework of apartheid while leaving its fundamental principles (including the homelands) unchanged.

The government was forced to accept the permanent presence of blacks in urban areas as well as the practical unfeasibility of the hitherto very strict forms of "influx control" (replacing it by "softer" means of control), not to mention the impossibility of a total removal of all blacks to the homelands even in the long run. It was hoping to "pacify" the black urban population by developing various plans to confer upon them limited rights at the local level (but not the upper levels of government). Furthermore, the urban (and rural) residential areas remained segregated based on race in accordance with the Group Areas Act

Group Areas Act was the title of three acts of the Parliament of South Africa enacted under the apartheid government of South Africa. The acts assigned racial groups to different residential and business sections in urban areas in a system of u ...

.

"Separate development" as a principle remained in force, and the apartheid regime went on to rely on the Bantustans as one of the main pillars of its policy in dealing with the black population. Until 1990, attempts continued to urge self-governing homelands to opt for independence (e.g. Lebowa, Gazankulu and KwaZulu) and on occasion the governments of self-governing homelands (e.g. KwaNdebele) themselves expressed interest in obtaining eventual independence.

It was also contemplated in circles of the ruling National Party to create additional nominally independent entities in the urban areas in the form of "independent" black "city states".

The long-term vision during this time was the creation of some form of a multi-racial "confederation of South African states" with a common citizenship, but separated into racially defined areas. Plans were made (of which only very few were realised) for the development of different "joint" institutions charged with mutual consultation, deliberation and a number of executive functions in relation to "general affairs" common to all population groups, insofar as these institutions would pose no threat to apartheid and the preservation of overall white rule. This "confederation" would include the so-called "common area"—meaning the bulk of South African territory outside of the homelands—under continued white-minority rule and limited power-sharing arrangements with the segregated Coloured

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

and Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

/Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

population groups, the independent and self-governing homelands as well as possible additional black entities in urban areas.

From 1990 to 1994, these "confederational" ideas were in principle still entertained by large parts of the National Party (and in various forms also by certain parties and groups of the white liberal opposition), but their overtly race-based foundations gradually became less pronounced in the course of the negotiations to end apartheid, and the focus shifted to securing "minority rights" (having in mind primarily the white population in particular) after an expected handover of power to the black majority. Federalist plans also met with support from some homeland governments and parties, most importantly the Inkatha Freedom Party

The Inkatha Freedom Party ( zu, IQembu leNkatha yeNkululeko, IFP) is a right-wing political party in South Africa. The party has been led by Velenkosini Hlabisa since the party's 2019 National General Conference. Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded t ...

, which was the ruling party of KwaZulu. But since especially the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

made it clear that the principles of "one man - one vote" and a unitary state were non-negotiable, (con-)federal schemes were eventually dropped. Because of this, the Inkatha Freedom Party threatened to boycott the April 1994 elections that ended apartheid and decided only in the last minute to participate in them after concessions had been made to them and as well as to the still-ruling National Party and several white opposition groups.

In the period leading up to the elections in 1994, several leaders in the independent and self-governing homelands (e.g. in Boputhatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

), who did not wish to relinquish their power, vehemently opposed the dismantling of the Bantustans and, in doing so, received support from white far-right parties, sections of the apartheid state apparatus and radical pro-apartheid groups like the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging

The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (), meaning "Afrikaner Resistance Movement", commonly known by its abbreviation AWB, is an Afrikaner nationalist paramilitary organisation in South Africa. Since its founding in 1973 by Eugène Terre'Blanche and ...

.

Dissolution

With the demise of the apartheid regime in South Africa in 1994, all Bantustans (both nominally independent and self-governing) were dismantled and their territories reincorporated into the Republic of South Africa with effect from 27 April 1994 (the day on which the Interim Constitution, which formally ended apartheid, came into force and the first democratic elections began) in terms of section 1(2) andSchedule 1 Schedule 1 may refer to:

* Schedule I Controlled Substances within the US Controlled Substances Act

* Schedule I Controlled Drugs and Substances within the Canadian Controlled Drugs and Substances Act

* Schedule I Psychotropic Substances within t ...

of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1993

The Interim Constitution was the fundamental law of South Africa from the first non-racial general election on 27 April 1994 until it was superseded by the final constitution on 4 February 1997. As a transitional constitution it required th ...

("Interim Constitution").

The drive to achieve this was spearheaded by the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

(ANC) as a central element of its programme of reform. Reincorporation was mostly achieved peacefully, although there was some resistance from the local elites, who stood to lose out on the opportunities for wealth and political power provided by the homelands. The dismantling of the homelands of Bophuthatswana and Ciskei was particularly difficult. In Ciskei, South African security forces had to intervene in March 1994 to defuse a political crisis.

From 1994, most parts of the country were constitutionally redivided into new provinces

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

.

Nevertheless, many leaders of former Bantustans or Homelands have had a role in South African politics since their abolition. Some had entered their own parties into the first non-racial election while others joined the ANC. Mangosuthu Buthelezi

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi (born 27 August 1928) is a South African politician and Zulu traditional leader who is currently a Member of Parliament and the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family. He was Chief Minister of the ...

was chief minister of his KwaZulu

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

It was led until its abolition in 1994 by Chief Mangosuth ...

homeland from 1976 until 1994. In post-apartheid South Africa he has served as president of the Inkatha Freedom Party

The Inkatha Freedom Party ( zu, IQembu leNkatha yeNkululeko, IFP) is a right-wing political party in South Africa. The party has been led by Velenkosini Hlabisa since the party's 2019 National General Conference. Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded t ...

and Minister of Home Affairs. Bantubonke Holomisa

Bantubonke Harrington Holomisa (born 25 July 1955) is a South African Member of Parliament and President of the United Democratic Movement.

Holomisa was born in Mqanduli, Cape Province. He joined the Transkei Defence Force in 1976 and had beco ...

, who was a general in the homeland of Transkei from 1987, has served as the president of the United Democratic Movement

The United Democratic Movement (UDM) is a centre-left, social-democratic, South African political party, formed by a prominent former National Party leader, Roelf Meyer (who has since resigned from the UDM), a former African National Congress ...

since 1997. General Constand Viljoen

General Constand Laubscher Viljoen, (28 October 1933 – 3 April 2020) was a South African military commander and politician. He co-founded the Afrikaner Volksfront (Afrikaner People's Front) and later founded the Freedom Front (now F ...

, an Afrikaner who served as chief of the South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

, sent 1,500 of his militiamen to protect Lucas Mangope

Kgosi Lucas Manyane Mangope (27 December 1923 – 18 January 2018) was the leader of the Bantustan (homeland) of Bophuthatswana. The territory he ruled over was distributed between the Orange Free State – what is now Free State – and North W ...

and to contest the termination of Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

as a homeland in 1994. He founded the Freedom Front

The Freedom Front Plus (FF Plus; af, Vryheidsfront Plus, ''VF Plus'') is a right-wing political party in South Africa that was formed (as the Freedom Front) in 1994. It is led by Pieter Groenewald. Its current stated policy positions include ...

in 1994. Lucas Mangope, former chief of the Motsweda Ba hurutshe-Boo-Manyane tribe of the Tswana and head of Bophuthatswana is president of the United Christian Democratic Party

The United Christian Democratic Party is a minor political party in South Africa. It was founded by Lucas Mangope, leader of the Bophuthatswana bantustan in 1997, as a successor to the Tswana National Party, and led by him for the first fifteen ...

, effectively a continuation of the ruling party of the homeland. Oupa Gqozo

Joshua Oupa Gqozo (; born 10 March 1952) was the military ruler of the former homeland of Ciskei in South Africa.

Early life

Gqozo was born in Kroonstad, Orange Free State on 10 March 1952, the son of a Christian minister.

In Afrikaans, Oupa ...

, the last ruler of Ciskei

Ciskei (, or ) was a Bantustan for the Xhosa people-located in the southeast of South Africa. It covered an area of , almost entirely surrounded by what was then the Cape Province, and possessed a small coastline along the shore of the Indian O ...

, entered his African Democratic Movement in the 1994 elections but was unsuccessful. The Dikwankwetla Party

Dikwankwetla Party of South Africa is a political party in the Free State province, South Africa. The party was founded by Kenneth Mopeli in 1975. The party governed the bantustan state of QwaQwa from 1975 to 1994.

It was one of the signatori ...

, which ruled Qwaqwa

QwaQwa was a bantustan ("homeland") in the central eastern part of South Africa. It encompassed a very small region of in the east of the former South African province of Orange Free State, bordering Lesotho. Its capital was Phuthaditjhaba. It ...

, remains a force in the Maluti a Phofung council where it is the largest opposition party. The Ximoko Party

The Ximoko Party is a minor political party in South Africa. It has no representation in the National Assembly or the provincial legislatures, but currently has 3 councillors at municipal level in Limpopo province as of 2019.

History

Formed ...

, which ruled Gazankulu, has a presence in local government in Giyani

Giyani is a town situated in the North-eastern part of Limpopo Province, South Africa. It is the administrative capital of the Mopani District Municipality, and a former capital of the defunct Gazankulu bantustan. The town of Giyani has seven s ...

. Similarly, the former KwaNdebele

KwaNdebele was a bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a semi-independent homeland for the Ndebele people. The homeland was created when the South African government purchased nineteen white-owned farms and install ...

chief minister George Mahlangu and others formed the Sindawonye Progressive Party which is one of the major opposition parties in Thembisile Hani Local Municipality

Thembisile Hani Local Municipality is located in the Nkangala District Municipality of Mpumalanga province, South Africa. It is a semi-urban local Municipality consisting of 57 villages within which there are 5 (five) established townships.

The m ...

and Dr JS Moroka Local Municipality (encompassing the territory of the former homeland).

List of Bantustans

Bantustans in South Africa

Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

, Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, meaning "gathering of the Tswana people"), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana ( tn, Riphaboliki ya Bophuthatswana; af, Republiek van Bophuthatswana), was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland"; an area set aside for mem ...

, Venda

Venda () was a Bantustan in northern South Africa, which is fairly close to the South African border with Zimbabwe to the north, while to the south and east, it shared a long border with another black homeland, Gazankulu. It is now part of the ...

and the Ciskei

Ciskei (, or ) was a Bantustan for the Xhosa people-located in the southeast of South Africa. It covered an area of , almost entirely surrounded by what was then the Cape Province, and possessed a small coastline along the shore of the Indian O ...

). The other six had limited self-government:

Nominally independent states

Self-governing entities

The first Bantustan was the Transkei, under the leadership ofChief Kaizer Daliwonga Matanzima

King Kaiser Daliwonga Mathanzima, misspelled Matanzima (15 June 1915 – 15 June 2003), was the long-term leader of Transkei. In 1950, when South Africa was offered to establish the Bantu Authorities Act, Matanzima convinced the Bunga to accep ...

in the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

for the Xhosa nation. KwaZulu, for the Zulu nation in Natal Province

The Province of Natal (), commonly called Natal, was a province of South Africa from May 1910 until May 1994. Its capital was Pietermaritzburg. During this period rural areas inhabited by the black African population of Natal were organized into ...

, was headed by a member of the Zulu royal family

The Zulu royal family consists of the king of the Zulus, his consorts, and all of his legitimate descendants. The legitimate descendants of all previous kings are also sometimes considered to be members.

History

King Misuzulu kaZwelithini's ...

chief Mangosuthu ("Gatsha") Buthelezi in the name of the Zulu king.

Lesotho

Lesotho ( ), officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a country landlocked country, landlocked as an Enclave and exclave, enclave in South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the Thabana Ntlenyana, highest mountains in Sou ...

and Eswatini

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its no ...

(formerly known as Swaziland) were not Bantustans; they have been independent countries and former British protectorates. These countries are mostly or entirely surrounded by South African territory and are almost totally dependent on South Africa. They have never had any formal political dependence on South Africa and were recognised as sovereign states by the international community from the time they were granted their independence by the UK in the 1960s.

Bantustans in South West Africa

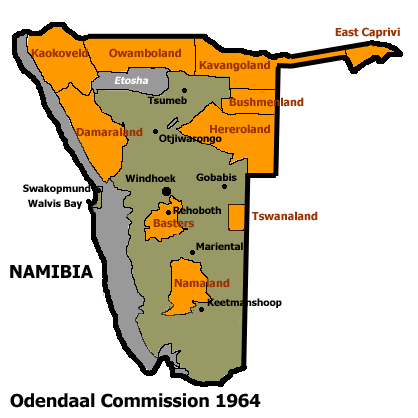

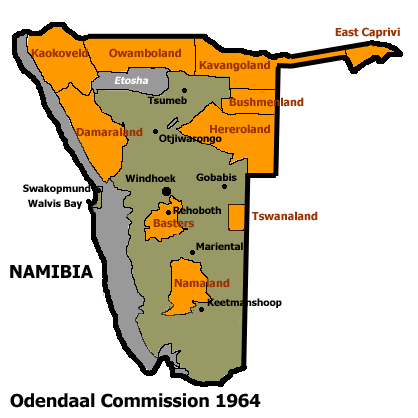

In the 1960s

In the 1960s South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, which was administering South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

under a League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

, came under increased international pressure regarding its minority White rule over the majority of Blacks. The solution envisaged by South Africa—the Odendaal Plan

Frans Hendrik Odendaal (1898–1966) (known as Fox Odendaal) was a South African politician, governor of the Transvaal province, best remembered for heading the commission that became known by his last name.

Odendaal Commission

In 1962 Odendaal ...

—was to separate the white and the non-white population, grant self-government to the isolated black territories, and thus make Whites the majority population in the vast remainder of the country. Moreover, it was envisaged that by separating each ethnic group and confining people by law to their restricted areas, discrimination by race would automatically disappear. The inspiration for the Odendaal Plan came, in part, from South African anthropologists.

The demarcated territories were called the ''bantustans'', and the remainder of the land was called the ''Police Zone''. Forthwith, all non-white people employed in the Police Zone became ''migrant workers'', and pass laws were established to police movement in and out of the bantustans.

The combined territory of all bantustans was roughly equal in size to the Police Zone. However, all bantustans were predominantly rural and excluded major towns. All harbours, most of the railway network and the tarred road infrastructure, all larger airports, the profitable diamond areas and the national parks were situated in the Police Zone.

Beginning in 1968, following the 1964 recommendations of the commission headed by Fox Odendaal, ten homelands similar to those in South Africa were established in South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

(present-day Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

). The term "Bantustan" is somewhat inappropriate in this context, since some of the peoples involved were Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in t ...

not Bantu, and the Rehoboth Basters

The Basters (also known as Baasters, Rehobothers or Rehoboth Basters) are a Southern African ethnic group descended from white European men and black African women, usually of Khoisan origin, but occasionally also enslaved women from the Cape, ...

are a complex case. Of these ten South West African homelands, only three were granted self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

(comparable to the Bantustans in South Africa) between 1973 and 1976.

In July 1980 the system was changed to one of separate governments ("representative authorities") as second-tier administrative units (responsible for a number of affairs like land tenure, agriculture, education up to the level of primary school teachers' training, health services, and social welfare and pensions) on the basis of ethnicity only and no longer based on geographically defined areas. Building upon institutions that had already been in existence since 1925 and 1962 respectively, representative authorities were also instituted for the White and Coloured population groups. No such representative authorities were established for the Himba and San peoples (mainly occupying their former homelands of Kaokoland and Bushmanland).

These ethnic second-tier governments were ''de facto'' suspended in May 1989, at the start of the transition to independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, and ''de jure'' abolished on 21 March 1990 (the day Namibia became independent) in accordance with Schedule 8 of the Constitution of Namibia

The Constitution of Namibia is the supreme law of the Republic of Namibia. Adopted on 9 February 1990, a month prior to Namibia's independence from apartheid South Africa, it was written by an elected constituent assembly.

Preamble

"Whereas ...

. The Basters lobbied unsuccessfully to maintain the autonomous status of Rehoboth, which had previously been autonomous under German rule. In the former Bantustan of East Caprivi

East Caprivi or Itenge was a bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Masubiya people. It was set up in 1972, in the very corner of the Namibian panhan ...

, Lozi nationalists launched an unsuccessful insurgency in an attempt to gain independence from Namibia which lasted until 1999.

Homelands (until 1980) / Representative Authorities (1980–1989/1990)

Usage in non-South African contexts

The term "bantustan" has become ageneric term

Trademark distinctiveness is an important concept in the law governing trademarks and service marks. A trademark may be eligible for registration, or registrable, if it performs the essential trademark function, and has distinctive character. Re ...

to refer in a disapproving sense to any area in which people are forced to live without full civil and political rights.

Palestinian enclaves

In the Middle East, thePalestinian enclaves

The Palestinian enclaves are areas in the West Bank designated for Palestinians under a variety of Israeli–Palestinian peace process, U.S. and Israeli-led proposals to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The enclaves are Israel and aparthe ...

in the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, as well as the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

, are often described as bantustans by critics of Israel's policies in the Palestinian territories

The Palestinian territories are the two regions of the former British Mandate for Palestine that have been militarily occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967, namely: the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. The I ...

. The term is used to refer to either the proposed areas in the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

designated for Palestinians

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

under a variety of US and Israeli-led proposals to end the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, beginning in the mid-20th century. Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, alongside other ef ...

, or the existing 165 "islands" which first took official form as Areas A and B under the 1995 Oslo II Accord. The Israeli-US peace plans, including the Allon Plan

The Allon Plan ( he, תוכנית אלון) was a plan to partition the West Bank between Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, create a Druze state in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, and return most of the Sinai Peninsula to Arab con ...

, the Drobles World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization ( he, הַהִסְתַּדְּרוּת הַצִּיּוֹנִית הָעוֹלָמִית; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the ...

plan, Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'' (); pl, Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ''Menakhem Volfovich Begin''; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. B ...

's plan, Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu (; ; born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Israel from 1996 to 1999 and again from 2009 to 2021. He is currently serving as Leader of the Opposition and Chairman of ...

's "Allon Plus" plan, the 2000 Camp David Summit, and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state have proposed an enclave-type territory, as has the more recent Trump peace plan. This has been criticized as the "Bantustan option".

Other examples

InIndian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

, the Sinhalese

Sinhala may refer to:

* Something of or related to the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka

* Sinhalese people

* Sinhala language, one of the three official languages used in Sri Lanka

* Sinhala script, a writing system for the Sinhala language

** Sinha ...

government of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

has been accused of turning Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

* Tamils, an ethnic group native to India and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka also called ilankai tamils

**Tamil Malaysians, Tamil people native to Malaysia

* Tamil language, nativ ...

areas into "bantustans". The term has also been used to refer to the living conditions of Dalits

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold varna system of Hinduism and were seen as forming ...

in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

In Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (al ...

, the increasing numbers of small states in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, following the breakup of Yugoslavia

The breakup of Yugoslavia occurred as a result of a series of political upheavals and conflicts during the early 1990s. After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yu ...

, have been referred to as "bantustans".

In Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, Catholic bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah

Matthew Hassan Kukah (born 31 August 1952) is the current bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sokoto.

In December 2020, Pope Francis appointed him as a member of the Dicastery on Integral Human Development.

Early life and education

Bishop ...

has referred to southern Kaduna State

Kaduna State ( ha, Jihar Kaduna جىِهَر كَدُنا; ff, Leydi Kaduna, script=Latn, ; kcg, Sitet Kaduna) is a state in northern Nigeria. The state capital is its namesake, the city of Kaduna which happened to be the 8th largest city in ...

as "one huge Bantustan of government neglect."

In Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Indian reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the '' Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

Ind ...

s are often compared to Bantustans due to the shared relationship between the two countries' systems of racial segregation.

See also

*Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

*Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, 1970

The Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, 1970 (Act No. 26 of 1970; subsequently renamed the Black States Citizenship Act, 1970 and the National States Citizenship Act, 1970) was a Self Determination or denaturalization law passed during the aparthei ...

*Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

* New village

*Volkstaat

The concept of a Volkstaat (, "People's State"), also called a Boerestaat, is a proposed view to establish an all-white Afrikaner homeland within the borders of South Africa, most commonly proposed as a fully independent Boer/Afrikaner natio ...

*Indian reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the '' Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

Ind ...

*Internal passport

An internal passport or a domestic passport is an identity document. Uses for internal passports have included restricting citizens of a subdivided state to employment in their own area (preventing their migration to richer cities or regions), cle ...

*Hukou system

''Hukou'' () is a system of household registration

Civil registration is the system by which a government records the vital events ( births, marriages, and deaths) of its citizens and residents. The resulting repository or database h ...

*Propiska Propiska is both a residency permit and a migration recording tool, generally referred to as an Internal passport:

* Propiska in the Russian Empire

* Propiska in the Soviet Union

* Propiska in Ukraine; see :uk:Прописка#Прописка в ...

*Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

*West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

*War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

Bantustan policy

*

Divide & Rule: South Africa's Bantustans

' by Barbara Rogers (1980) * Pelliccioni Franco, LO SVILUPPO DELLE "BANTU HOMELANDS" NEL SUDAFRICA, 197

(1974) {{Authority control Lands reserved for indigenous peoples South African English Political terminology in South Africa 1994 disestablishments in South Africa