Butley Priory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of

Butley Priory was founded at the time when nearby

Butley Priory was founded at the time when nearby

Excavations in 1931-1933 in and around the farm, led by J.N.L. Myres, revealed much about the layout and phases of development of the priory church and claustral buildings, which had been on a grand scale. The rectangular area now occupied by farm buildings was the site of the central complex and contains some standing remains of the

Excavations in 1931-1933 in and around the farm, led by J.N.L. Myres, revealed much about the layout and phases of development of the priory church and claustral buildings, which had been on a grand scale. The rectangular area now occupied by farm buildings was the site of the central complex and contains some standing remains of the

Myres believed that the plan of the priory complex was laid out in the founding phase, but that the only masonry construction belonging to Ranulf's time was represented by the footings of the original church, later rebuilt. With a large west doorway, its

Myres believed that the plan of the priory complex was laid out in the founding phase, but that the only masonry construction belonging to Ranulf's time was represented by the footings of the original church, later rebuilt. With a large west doorway, its

The first construction of the stone conventual buildings took place in the years of the de Auberville patronage, c.1190-1240. The nave of the church formed the north side of the

The first construction of the stone conventual buildings took place in the years of the de Auberville patronage, c.1190-1240. The nave of the church formed the north side of the  On the east side of the cloister, running south from the south transept of the church, was the

On the east side of the cloister, running south from the south transept of the church, was the

Standing centrally on the priory's northern precinct boundary, the gatehouse was built in the early 14th century to provide a grand entrance and to accommodate important visitors. Substantially original, it is called one of the finest examples of

Standing centrally on the priory's northern precinct boundary, the gatehouse was built in the early 14th century to provide a grand entrance and to accommodate important visitors. Substantially original, it is called one of the finest examples of

The exterior decorative work covers the whole of the north and south gabled frontages and the faces of the north towers, in a dramatic scheme integral to the proportions of the building. The upper chamber over the main entrance has on both fronts a single tall arched window of pierced stone tracery: a central

The exterior decorative work covers the whole of the north and south gabled frontages and the faces of the north towers, in a dramatic scheme integral to the proportions of the building. The upper chamber over the main entrance has on both fronts a single tall arched window of pierced stone tracery: a central  The north towers beside the entrance also have blind tracery, and the two inner buttresses, which face forward, have niches to contain statues which are lost. A figure is shown in the west niche in Buck's engraving. These linked thematically with sculptures in the three niches set up in the north gable, the central figure there presumably being

The north towers beside the entrance also have blind tracery, and the two inner buttresses, which face forward, have niches to contain statues which are lost. A figure is shown in the west niche in Buck's engraving. These linked thematically with sculptures in the three niches set up in the north gable, the central figure there presumably being

Sir Guy Ferre the younger acquired the manor of Benhall with its patronage of Butley Priory and Leiston Abbey in or soon after 1290 (confirmed 1294), from Sir Nicholas de Crioll. He had trouble with poachers there in 1292. He had held this title (as from the

Sir Guy Ferre the younger acquired the manor of Benhall with its patronage of Butley Priory and Leiston Abbey in or soon after 1290 (confirmed 1294), from Sir Nicholas de Crioll. He had trouble with poachers there in 1292. He had held this title (as from the  Sir Guy became a trusted ducal commissioner through the Process of Périgueux (a negotiation to end French encroachment in Gascony), though recalled for some months in 1312 to help release the king from the

Sir Guy became a trusted ducal commissioner through the Process of Périgueux (a negotiation to end French encroachment in Gascony), though recalled for some months in 1312 to help release the king from the

The last 50 years of the priory are unusually well-documented. The names of the canons themselves, and their observations and complaints about the management of the convent, can be followed in a series of Visitations by the Bishops of Norwich, commencing in 1492 with that of Bishop

The last 50 years of the priory are unusually well-documented. The names of the canons themselves, and their observations and complaints about the management of the convent, can be followed in a series of Visitations by the Bishops of Norwich, commencing in 1492 with that of Bishop

Augustine Rivers (Prior, 1509-1528) spent a substantial amount of his own money on repairs to the buildings, and cleared the priory's debt, though the canons complained that the food was not very good, the infirmary was not maintained, and the roofs of the church and refectory leaked when it rained. At the 1520 Visitation there were only 11 canons, and they were reminded that they must remain silent in the refectory, dormitory and cloister. By 1526 the numbers had increased to 16 (including the prior) but the drains were becoming blocked, and the roofs still leaked.

Augustine Rivers (Prior, 1509-1528) spent a substantial amount of his own money on repairs to the buildings, and cleared the priory's debt, though the canons complained that the food was not very good, the infirmary was not maintained, and the roofs of the church and refectory leaked when it rained. At the 1520 Visitation there were only 11 canons, and they were reminded that they must remain silent in the refectory, dormitory and cloister. By 1526 the numbers had increased to 16 (including the prior) but the drains were becoming blocked, and the roofs still leaked.

However this priorate was particularly memorable for its distinguished guests, who came to enjoy the surrounding countryside. Soon after her marriage to Charles Brandon (1st Duke of Suffolk), Mary Tudor stayed at the priory in 1515/16, with her husband in 1518, and again in 1519, always in late September. She stayed for two months in summer 1527, and in the following year she and the Duke went fox-hunting in nearby Staverton Park (an ancient oakland deer-park), where they dined and had musicians playing. Staverton had been leased to the priory in 1517 by the second Duke of Norfolk, at whose funeral at

However this priorate was particularly memorable for its distinguished guests, who came to enjoy the surrounding countryside. Soon after her marriage to Charles Brandon (1st Duke of Suffolk), Mary Tudor stayed at the priory in 1515/16, with her husband in 1518, and again in 1519, always in late September. She stayed for two months in summer 1527, and in the following year she and the Duke went fox-hunting in nearby Staverton Park (an ancient oakland deer-park), where they dined and had musicians playing. Staverton had been leased to the priory in 1517 by the second Duke of Norfolk, at whose funeral at

Further researches into the priory itself, its involvement with the life of the surrounding communities, its later owners, and how its impact on the landscape and population devolved into recent times, are brought to life in a recent study.

The monastery site was purchased by William Forth (died 1558) and a large (now lost) house was built by his son Robert adjacent to the Gatehouse. This new mansion was derelict, and the Gatehouse ruinous, by 1738 when illustrated by

Further researches into the priory itself, its involvement with the life of the surrounding communities, its later owners, and how its impact on the landscape and population devolved into recent times, are brought to life in a recent study.

The monastery site was purchased by William Forth (died 1558) and a large (now lost) house was built by his son Robert adjacent to the Gatehouse. This new mansion was derelict, and the Gatehouse ruinous, by 1738 when illustrated by

Butley Priory

{{coord, 52.091, 1.465, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title Monasteries in Suffolk Augustinian monasteries in England Grade I listed buildings in Suffolk

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of Canons regular

Canons regular are priests who live in community under a rule ( and canon in greek) and are generally organised into religious orders, differing from both secular canons and other forms of religious life, such as clerics regular, designated by a ...

(Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

, Black canons) in Butley, Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, dedicated to The Blessed Virgin Mary. It was founded in 1171 by Ranulf de Glanville

Ranulf is a masculine given name in the English language. It is derived from the Old Norse name ''Reginúlfr''. This Old Norse personal name is composed of two elements: the first, ''regin'', means "advice", "decision" (and also "the gods"); the s ...

(c. 1112-1190), Chief Justiciar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalent ...

to King Henry II (1180-1189), and was the sister foundation to Ranulf's house of White canons (Premonstratensians

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their habit), is a religious order of canons regular of the Catholic Church ...

) at Leiston Abbey

Leiston Abbey outside the town of Leiston, Suffolk, England, was a religious house of Canons Regular following the Premonstratensian rule (White canons), dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, St Mary. Founded in c. 1183 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 11 ...

, a few miles to the north, founded c. 1183. Butley Priory was suppressed in 1538.

Although only minor fragments of the priory church and some masonry of the convent survive at Abbey Farm, the underground archaeology was expertly investigated and interpreted in 1931-33, shedding much light on the lost buildings and their development. The remaining glory of the priory is its 14th-century Gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the mos ...

, incorporating the former guest quarters. This exceptional building, largely intact, reflects the interests of the manorial patron Guy Ferre the younger (died 1323), Seneschal of Gascony The Seneschal of Gascony was an officer carrying out and managing the domestic affairs of the lord of the Duchy of Gascony. During the course of the twelfth century, the seneschalship, also became an office of military command. After 1360, the off ...

to King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

1308-1309, and was probably built in the priorate of William de Geytone (1311–32). Having fallen into decay after 1538, it was restored to use as a private house about 280 years ago.

Near-complete lists of the priors survive from 1171 to 1538, together with foundation deeds, deeds of grant, and records pertaining to the priory's manors, holdings and visitations. In addition there is a Register or Chronicle made in the last decades of the priory, and there are sundry documents concerning its suppression. Its post-Dissolution history has also been investigated. In private ownership in the area of the Suffolk Heritage Coast, the Gatehouse is now a Grade I listed building and is used as a venue for private functions, corporate events or retreats.

Foundation

The founders

Butley Priory was founded at the time when nearby

Butley Priory was founded at the time when nearby Orford Castle

Orford Castle is a castle in Orford in the English county of Suffolk, northeast of Ipswich, with views over Orford Ness. It was built between 1165 and 1173 by Henry II of England to consolidate royal power in the region. The well-preserved ...

was being built by King Henry II to consolidate his power in Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, a region dominated by Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk

Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk (1095–1177) was the second son of Roger Bigod (also known as Roger Bigot) (died 1107), sheriff of Norfolk and royal advisor, and Adeliza, daughter of Robert de Todeni.

Early years

After the death of his eld ...

(died c. 1176). Ranulf de Glanvill, born in Stratford St Andrew, Sheriff of Yorkshire

The Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the Sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of the responsibilities associated with the post have been transferred elsewhere o ...

from 1163 to 1170, was loyal to the king, and married Bertha, daughter of Theobald de Valoines, Lord of Parham ( fl. 1135). He became mentor to the King's son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, and to Hubert Walter

Hubert Walter ( – 13 July 1205) was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor. As chancellor, Walter b ...

, son of his wife's sister Maud de Valoines. A kinsman, Bartholomew de Glanvill, was Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk

This is a list of Sheriffs of Norfolk and Suffolk. The Sheriff (since 1974 called High Sheriff) is the oldest secular office under the Crown and is appointed annually by the Crown. He was originally the principal law enforcement officer in the c ...

from 1169, and Constable of Orford Castle. Hugh Bigod's widowed countess, Gundreda, was the founder of Bungay Priory

Bungay Priory was a Benedictine nunnery in the town of Bungay in the English county of Suffolk. It was founded c. 1160-1185 by the Countess Gundreda, wife or widow of Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, upon lands of her '' maritagium'' and was ...

, and remarried to Roger de Glanvill; Ranulf witnessed the royal confirmation.

The site of Butley Priory, on rising ground overlooking wetland levels fed by waters tributary to the tidal Butley River

The Butley River or Butley Creek is a tributary of the River Ore in the English county of Suffolk. ...

, was an estate called Brochous, granted as '' maritagium'' (marriage endowment) to Bertha de Valoines by her father Theobald. This part of Butley lies in the Hundred of Plomesgate: at the Domesday Survey

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

it formed a manor (''Carlton'') held by one Hamo from Count Alan, presumably part of the de Valoines tenure which from Parham (in Plomesgate) owed service to the Honour of Richmond

The Honour of Richmond (or English feudal barony of Richmond) in north-west Yorkshire, England was granted to Count Alan Rufus (also known as Alain le Roux) by King William the Conqueror sometime during 1069 to 1071, although the date is uncertai ...

.

Ranulf founded the house in 1171 for 36 canons under a prior, for whom he selected Gilbert, formerly a precentor

A precentor is a person who helps facilitate worship. The details vary depending on the religion, denomination, and era in question. The Latin derivation is ''præcentor'', from cantor, meaning "the one who sings before" (or alternatively, "first ...

at Blythburgh Priory

Blythburgh Priory was a medieval monastic house of Augustinian canons, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, located in the village of Blythburgh in Suffolk, England. Founded in the early 12th century, it was among the first Augustinian houses in ...

. Ranulf endowed it with the churches of Butley, Capel St Andrew

Capel St Andrew is a village and a civil parish in the East Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England. It is near the larger settlement of Orford.

Capel St Andrew is close to the River Butley, which is a tributary to the River Ore. ...

, Bawdsey

Bawdsey is a village and civil parish in Suffolk, eastern England. Located on the other side of the river Deben from Felixstowe, it had an estimated population of 340 in 2007, reducing to 276 at the Census 2011.

Bawdsey Manor is notable as the ...

, Benhall, Farnham

Farnham ( /ˈfɑːnəm/) is a market town and civil parish in Surrey, England, around southwest of London. It is in the Borough of Waverley, close to the county border with Hampshire. The town is on the north branch of the River Wey, a trib ...

, Wantisden

Wantisden is a small village and civil parish in the East Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England. Largely consisting of a single farm and ancient woodland ( Staverton Park and The Thicks), most of its 30 residents live on the farm estate. ...

, Leiston

Leiston ( ) is an English town in the East Suffolk non-metropolitan district of Suffolk, near Saxmundham and Aldeburgh, about from the North Sea coast, north-east of Ipswich and north-east of London. The town had a population of 5,508 at the ...

and Aldringham

Aldringham is a village in the Blything Hundred of Suffolk, England. The village is located 1 mile (1½ km) south of Leiston and 3 miles (4½ km) northwest of Aldeburgh close to the North Sea coast. The parish includes the coastal village of Th ...

, and a fourth part of the church of Glemham, together with various lands in Butley. Ranulf and Bertha also founded a leper hospital

A leper colony, also known by many other names, is an isolated community for the quarantining and treatment of lepers, people suffering from leprosy. ''M. leprae'', the bacterium responsible for leprosy, is believed to have spread from East Afr ...

at West Somerton

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

in Norfolk, for three lepers, dedicated to St Leonard, and placed it under the governance of Butley Priory.

Ranulf was Sheriff of Lancashire

The High Sheriff of Lancashire is an ancient officer, now largely ceremonial, granted to Lancashire, a county in North West England. High Sheriff, High Shrievalties are the oldest secular titles under the Crown, in England and Wales. The High She ...

and Keeper of the Honour of Richmond

The Honour of Richmond (or English feudal barony of Richmond) in north-west Yorkshire, England was granted to Count Alan Rufus (also known as Alain le Roux) by King William the Conqueror sometime during 1069 to 1071, although the date is uncertai ...

at the time of the Revolt of 1173-74, and, following the defeat of Hugh Bigod at the Battle of Fornham

The Battle of Fornham was a battle fought during the Revolt of 1173–74.

Background

The Revolt began in April 1173 and resulted from the efforts of King Henry II of England to find lands for his youngest son, Prince John. John's other three l ...

in 1173, Glanvill surprised the Scots at the Battle of Alnwick in 1174 and made William the Lion

William the Lion, sometimes styled William I and also known by the nickname Garbh, "the Rough"''Uilleam Garbh''; e.g. Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1214.6; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1213.10. ( 1142 – 4 December 1214), reigned as King of Scots from 11 ...

the king's prisoner. Resuming office as Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1175, he became Chief Justiciar in 1180 (succeeding Richard de Luci

Richard de Luci (or Lucy; 1089 – 14 July 1179) was first noted as High Sheriff of Essex, after which he was made Chief Justiciar of England.

Biography

His mother was Aveline, the niece and heiress of William Goth. In the charter for Sées Ca ...

). Butley seems to have held the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

of St Olave Jewry with St Stephen Coleman Street, in London, from the Canons of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

by 1181. So it is shown in the accounts of Ralph de Diceto

Ralph de Diceto (or Ralph of Diss; c. 1120c. 1202) was archdeacon of Middlesex, dean of St Paul's Cathedral (from c. 1180), and author of two chronicles, the ''Abbreviationes chronicorum'' and the ''Ymagines historiarum''.

Early career

Ralph is ...

, who later made a grant of them to Butley, out of the fee of Ranulf's son-in-law Ralph de Ardern, acknowledged under the seal of Prior Gilbert.

Being granted the manor of Leiston, a few miles north of Butley, Ranulf founded the Premonstratensian Abbey there c. 1183 under Prior Robert, on a marshland isle near the sea. Among its endowments was the church of Knodishall

Knodishall, a village in Suffolk, England, lies south-east of Saxmundham, south-west of Leiston, and 3 miles from the coast, in the Blything Hundred. Most dwellings are now at Coldfair Green; just a few remain in the original village by the ...

, which with the assent of Gilbert and Robert was transferred to Butley Priory in exchange for their churches of Leiston and Aldringham. Ranulf died at the Siege of Acre Siege of Acre may refer to:

* Siege of Acre (1104), following the First Crusade

*Siege of Acre (1189–1191), during the Third Crusade

* Siege of Acre (1263), Baibars laid siege to the Crusader city, but abandoned it to attack Nazareth.

*Siege of A ...

in 1190, having divided his estates between his three daughters. In the descent of Bertha's ''maritagium'' to her heirs in blood, the patronage of the two convents passed with the manor of Benhall (in Plomesgate) to Matilda, and to her husband William de Auberville of Westenhanger

Stanford is a village and civil parish in Kent, England. It is part of the Folkestone and Hythe district.

It has been divided by the M20 into Stanford North and Stanford South. The Stanford Windmill is to the north of the M20 and west of the a ...

in Kent.

The patronage, 1190-1300

William and Matilda de Auberville foundedLangdon Abbey

Langdon Abbey () was a Premonstratensian abbey near West Langdon, Kent, founded in about 1192 and dissolved in 1535, reportedly the first religious house to be dissolved by Henry VIII. The visible remains of the abbey are now confined to the ...

, a Premonstratensian house near West Langdon

West Langdon is a village in the Dover district of Kent, England. It is located five miles north of Dover town. The population of the village is included in the civil parish of Langdon.

The name ''Langdon'' derives from an Old English

...

, Kent, in 1192, as from Leiston Abbey: the foundation was given under the hand of Abbot Robert of Leiston and attested by Prior Gilbert of Butley. In 1194 Matilda's nephews, Thomas de Ardene and Ranulf fitz Robert, brought suit against the de Aubervilles for their share of Glanville's inheritance: William de Auberville died c. 1195, and his heirs became wards of Hubert Walter. In c. 1195 Butley elected its second prior, William (c. 1195-1213), a choice confirmed by Pope Celestinus III (1191-1199) who granted them the perpetual right of free election (as also to Leiston).

Philippa Golafre quitclaim

Generally, a quitclaim is a formal renunciation of a legal claim against some other person, or of a right to land. A person who quitclaims renounces or relinquishes a claim to some legal right, or transfers a legal interest in land. Originally a c ...

ed half the Hundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 and preceding 101.

In medieval contexts, it may be described as the short hundred or five score in order to differentiate the English and Germanic use of "hundred" to de ...

of Plomesgate to Hugh de Auberville, heir of William and Matilda, at Easter 1209. Hugh died c. 1212, whereupon William Briwere

William Briwere (died 1244) was a medieval Bishop of Exeter.

Early life

Briwere was the nephew of William Brewer, a baron and political leader during King Henry III of England's minority.Vincent ''Peter des Roches'' p. 213 Nothing else is k ...

paid 1000 marks for custody of his lands, his heirs and their marriages. In 1213 Prior Robert received the advowson of the church of Weybread from Alan de Withersdale. Hugh's brother Robert de Auberville became a justiciar and constable of Hastings Castle

Hastings Castle is a keep and bailey castle ruin situated in the town of Hastings, East Sussex. It overlooks the English Channel, into which large parts of the castle have fallen over the years.

History

Immediately after landing in England ...

during the 1220s. Joan de Auberville, wife of Ralph de Sunderland, held Benhall in 1225, but with the patronage of Butley Priory it descended to Hugh's son William. The Prior Adam ( fl. 1219-1235), who carried through a painful dispute with the prioress of Campsey Priory

Campsey Priory, (''Campesse'', ''Kampessie'', etc.), was a religious house of Augustinian canonesses at Campsea Ashe, Suffolk, about 1.5 miles (2.5 km) south east of Wickham Market. It was founded shortly before 1195 on behalf of two of his ...

in 1228-1230, probably hosted Henry III's visit in March 1235. William de Auberville attempted to assert rights of advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

at Butley Priory, but was successfully resisted, and came to a concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

by which he quitclaim

Generally, a quitclaim is a formal renunciation of a legal claim against some other person, or of a right to land. A person who quitclaims renounces or relinquishes a claim to some legal right, or transfers a legal interest in land. Originally a c ...

ed advowson to the prior and convent and renounced rights of wardship during vacancy. At much the same time his kinsman Robert de Valoines did the same for Campsey Priory.

William died before 28 January 1248, and soon afterwards, 30 March to 1 April, the King visited both Leiston and Butley. William's daughter and heir Joan de Auberville married first (1248) Henry de Sandwich, and secondly (before June 1255) Nicholas de Crioll

Nicholas de Crioll (Cryoyll, Kerrial or Kyriel) (died c. February 1272), of a family seated in Kent, was Warden of the Cinque Ports, Constable of Dover Castle and Keeper of the Coast during the early 1260s. His kinsman Bertram de Criol (died 1256 ...

of Croxton Kerrial

Croxton Kerrial (pronounced �kroʊsən ˈkɛrɨl is a village and civil parish in the Melton borough of Leicestershire, England, south-west of Grantham, north-east of Melton Mowbray, and west of Leicestershire's border with Lincolnshire. Th ...

(died 1272), to whom she brought the Westenhanger estates. In dealing with her inheritance, at assizes of 1258 they claimed from Joan's mother Isabel two parts of the manor of Benhall with its appurtenances. In this interval were Priors Peter (fl. 1251) and Hugh (fl. 1255), and after it came Prior Walter (by 1260-1268). Butley received an advowson in Essex in 1261 from Robert de Stuteville, and another in Norfolk from Lady Cassandra Baynard in 1268.

Nicholas de Crioll (who with Bertram de Criol

Sir Bertram de Criol (Criel, Crioill, Cyroyl, or Kerrial, etc.) (died 1256) was a senior and trusted Steward and diplomat to King Henry III. He served as Constable and Keeper of Dover Castle, Keeper of the Coast and of the Cinque Ports, Keeper of ...

had served the king in Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

in 1248-49 and 1253-54 and was entrusted with the Cinque Ports

The Confederation of Cinque Ports () is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier (Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to th ...

and other commands in Kent in 1263) gave Benhall with its appurtenance

An appurtenance is something subordinate to or belonging to another larger, principal entity, that is, an adjunct, satellite or accessory that generally accompanies something else.dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

...

upon his bride Margery, daughter of Sir Gilbert Pecche. Prior Robert, who succeeded Walter, had given way to the troubled Prior Thomas by 1277/78. Margery was living when in c. 1290 her husband gave the manor and its appurtenances to Guy Ferre the younger, who for this concord gave to de Crioll a Sore-hawk. Nicholas de Crioll the younger, who died in 1303, retained his patronage of Langdon Abbey.

The Priory church and cloister ranges

Excavations in 1931-1933 in and around the farm, led by J.N.L. Myres, revealed much about the layout and phases of development of the priory church and claustral buildings, which had been on a grand scale. The rectangular area now occupied by farm buildings was the site of the central complex and contains some standing remains of the

Excavations in 1931-1933 in and around the farm, led by J.N.L. Myres, revealed much about the layout and phases of development of the priory church and claustral buildings, which had been on a grand scale. The rectangular area now occupied by farm buildings was the site of the central complex and contains some standing remains of the Refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminaries. The name derives from the La ...

or Frater on the south side, and of the Reredorter

The reredorter or necessarium (the latter being the original term) was a communal latrine found in mediaeval monasteries in Western Europe and later also in some New World monasteries.

Etymology

The word is composed from dorter and the Middle ...

(which stood apart from the east claustral range) on the east side. The central tower of the priory church was still standing when an engraving of the Gatehouse was made in 1738, and sizeable parts of the church's eastern works remained (and were illustrated by Isaac Johnson) before being removed in c. 1805.

In addition to foundations and buried walls, the excavators found a large number of decorative tiles of various kinds. They belonged to different periods of building. Of special note were several examples of 13th century "embossed" tiles, about 5 inches square and an inch thick, with striking designs of symmetrical interlacing foliage and winged heraldic animals under clear green glaze. These had been pressed from moulds shaping the images in rounded bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

. Others of later types, some still in their original floor positions, were of pressed heraldic, geometric or foliate designs in a red clay matrix with white ball clay

Ball clays are kaolinitic sedimentary clays that commonly consist of 20–80% kaolinite, 10–25% mica, 6–65% quartz. Localized seams in the same deposit have variations in composition, including the quantity of the major minerals, accessory ...

infilling, or in some cases painted in slip

Slip or SLIP may refer to:

Science and technology Biology

* Slip (fish), also known as Black Sole

* Slip (horticulture), a small cutting of a plant as a specimen or for grafting

* Muscle slip, a branching of a muscle, in anatomy

Computing and ...

, before glazing. They show that the convent church and cloisters were not visually austere. The early embossed tiles have been found at related sites including Orford, Leiston Abbey and Campsey Priory

Campsey Priory, (''Campesse'', ''Kampessie'', etc.), was a religious house of Augustinian canonesses at Campsea Ashe, Suffolk, about 1.5 miles (2.5 km) south east of Wickham Market. It was founded shortly before 1195 on behalf of two of his ...

, and the later types are also characteristically East Anglian. The Butley tiles are a core reference collection in developing knowledge of this subject.

The priory church

Myres believed that the plan of the priory complex was laid out in the founding phase, but that the only masonry construction belonging to Ranulf's time was represented by the footings of the original church, later rebuilt. With a large west doorway, its

Myres believed that the plan of the priory complex was laid out in the founding phase, but that the only masonry construction belonging to Ranulf's time was represented by the footings of the original church, later rebuilt. With a large west doorway, its nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

was 132 feet long and 34 feet wide, without aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

s, opening into a crossing with north and south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building withi ...

s each about 28 feet square. This stood across the open area just north of the old farm buildings. The presbytery, also without aisles, extended some distance eastwards across the present farm track towards the cottages and lane opposite, but later rebuilding and digging had removed its footprint.

In the second phase of patronage, c. 1190-1240, the church was almost entirely rebuilt. The eastern end of the church was enlarged to some 70 feet east of the crossing, probably forming five bays, with choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

aisles, probably of four bays, to north and south. The north transept was extended 12 feet northwards, and small outer chapels were added to the east side of both transepts. The nave was rebuilt with 10-foot aisles on both north and south sides, the eight columns of the nine nave arcades resting on the former nave footings. New substantial piers Piers may refer to:

* Pier, a raised structure over a body of water

* Pier (architecture), an architectural support

* Piers (name), a given name and surname (including lists of people with the name)

* Piers baronets, two titles, in the baronetages ...

were built for the crossing, no doubt to support the tower above. The west wall was completely rebuilt two feet east of its former position. A turret staircase is thought to have existed at the north-west corner. The church was thus some 235 feet in overall length.

During the 14th century the choir aisles were rebuilt to the full width of the transepts, and to a length of five bays. The east walls of the transepts were replaced, each containing a single arch (one of which survives). A beautifully carved piscina

A piscina is a shallow basin placed near the altar of a church, or else in the vestry or sacristy, used for washing the communion vessels. The sacrarium is the drain itself. Anglicans usually refer to the basin, calling it a piscina. For Roman ...

of this date, thought to have come from the priory church, is preserved in the Gatehouse. The south choir aisle contained a number of important burials in stone coffins.

The cloister and ranges

The first construction of the stone conventual buildings took place in the years of the de Auberville patronage, c.1190-1240. The nave of the church formed the north side of the

The first construction of the stone conventual buildings took place in the years of the de Auberville patronage, c.1190-1240. The nave of the church formed the north side of the cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

. Myres observed that a cloister of 98 feet square had originally been envisaged, but was curtailed by ten feet on the north side to make room for the addition of the south aisle of the nave. Butley's early 13th-century cloister walkways had open arcading, formed by a low wall with pairs of detached Purbeck marble

Purbeck Marble is a fossiliferous limestone found in the Isle of Purbeck, a peninsula in south-east Dorset, England. It is a variety of Purbeck stone that has been quarried since at least Roman times as a decorative building stone.

Geology

Strat ...

columns set transversely upon it with double capitals and bases (over 16 inches breadth) ornamented with carving of stiff-leaved foliage, supporting a series of equal arches. This opened from all sides onto a central garth

Garth may refer to:

Places

* Garth, Alberta, Canada

* Garth, Bridgend, a village in south Wales

:* Garth railway station (Bridgend)

* Garth, Ceredigion, small village in Wales

* Garth, Powys, a village in mid Wales

:* Garth railway station (Powy ...

71 feet from east to west and 62 feet north to south. These arcades were replaced in the 14th century by walls which probably supported glazed windows, both for greater comfort and because the purbeck marble had apparently deteriorated where exposed to the weather. They were again rebuilt on the east and south sides at a later date.

On the east side of the cloister, running south from the south transept of the church, was the

On the east side of the cloister, running south from the south transept of the church, was the sacristy

A sacristy, also known as a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christian churches for the keeping of vestments (such as the alb and chasuble) and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records.

The sacristy is usually located ...

or vestry; then the chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

, internally 48 feet long, extending back across the present farm path, and having a frontage of about 20 feet onto the cloister walk. To its south was the dormitory

A dormitory (originated from the Latin word ''dormitorium'', often abbreviated to dorm) is a building primarily providing sleeping and residential quarters for large numbers of people such as boarding school, high school, college or university s ...

with an undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground (street-level) area which is relatively open ...

of some 99 feet, and a day stair descending into the cloister walk. None of this now stands above ground. Many of the interior walls at ground level were probably of 14th century construction. From its south end a passageway ran east to the north end of the reredorter

The reredorter or necessarium (the latter being the original term) was a communal latrine found in mediaeval monasteries in Western Europe and later also in some New World monasteries.

Etymology

The word is composed from dorter and the Middle ...

, a separate building originally 60 feet by 18 feet. A thatched barn to the east of the farm path incorporates its standing walls, thrown in with that part of the passageway which stood at its north end.

On the south side of the cloister was the Refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminaries. The name derives from the La ...

range, 22 feet wide and at least 70 feet long, now represented by a great barn which incorporates some of its masonry. At its north-western corner is a scar, to the full height of the eaves, showing where the lost western range adjoined it. At its north end the western range was built integrally with the south aisle of the nave, showing that it, too was of the early 13th century construction. This was presumably the cellarer

A cellarium (from the Latin ''cella'', "pantry"), also known as an ''undercroft'', was a storehouse or storeroom, usually in a medieval monastery or castle. In English monasteries, it was usually located in or under the buildings on the west range ...

's range, and had included a porch or gateway in its west wall.

The wharf

The priory stood on the margin of open levels extending towards the tidalButley River

The Butley River or Butley Creek is a tributary of the River Ore in the English county of Suffolk. ...

, which is now strongly embanked. Along the south side of the priory enclosure, where the ground slopes down to the level, a creek was modified and brought into use as a navigable waterway. Excavations revealed a massive 60-foot long wall, braced by three buttresses, forming an embankment, to one end of which a roadway led from the direction of the monastery buildings to the water's edge. Beyond this was a further wooden revetment and evidence of a landing stage or platform for storage buildings. Investigations showed that it had continued in use long after the closure of the monastery before being deliberately filled in. The channel (now no more than a narrow stream) and its dock served the priory both for drainage and transport. The management of a partially wetland environment and its resources, and access to water communication routes, were the practical benefits of its marshy seclusion: the liminal nature of the landscape had both material and spiritual advantages. The monastic fishponds were in the north-western part of the site.

The Priory Gatehouse

Standing centrally on the priory's northern precinct boundary, the gatehouse was built in the early 14th century to provide a grand entrance and to accommodate important visitors. Substantially original, it is called one of the finest examples of

Standing centrally on the priory's northern precinct boundary, the gatehouse was built in the early 14th century to provide a grand entrance and to accommodate important visitors. Substantially original, it is called one of the finest examples of Decorated Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

architecture in Suffolk, and one of the most complete and interesting monastic entrances surviving. Its exuberant flint flushwork is the first blossoming of that technique, later so widespread in East Anglian religious architecture, and its heraldic display was ambitious in content and architecturally innovative. The impressive rib-vaulted central entrance passage and side chambers dictated the need for large external buttresses. A portal

Portal often refers to:

* Portal (architecture), an opening in a wall of a building, gate or fortification, or the extremities (ends) of a tunnel

Portal may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Gaming

* ''Portal'' (series), two video games ...

between the temporal and cloistered worlds, the Gatehouse was in its time a prestigious addition to the priory, and remains a monument to the priory itself and to the taste and resources of its patron. It also attracted some distinguished visitors.

The architecture

The gateway consists of a central block of about 31 by 37 feet (external), the whole internal space (some 22 by 30 feet) forming a rib-vaulted passageway of two bays running longitudinally with a great chamber above. The north (external) entrance has a larger arch to the west for visitors riding on horseback and for vehicles, and a smaller entry beside it for pedestrians, and had wooden gates. The south entrance has a single central arch. The north and south walls rise to high gables. This structure is flanked by two equal blocks some 23 feet east and west (external) containing side chambers about 18 feet square internally, with rib vaults supporting domed brickwork ceilings, and with upper rooms. They stand to the north: the south end of the central block projects. Their walls were probablycrenellated

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interva ...

and their roofs crossed into the central roof. The central passage floor level was about 6 inches below present ground level, and that of the side chambers lower. Two smaller tower blocks some 13 foot square (external) extend to the north, each with one side wall angled out to flare away from the piers of the gateway arches. These gave admission through two half-arches braced against the piers. Very large angled buttresses project from every external corner of the building and rise to the upper storey. All is of one construction.

The exterior decorative work covers the whole of the north and south gabled frontages and the faces of the north towers, in a dramatic scheme integral to the proportions of the building. The upper chamber over the main entrance has on both fronts a single tall arched window of pierced stone tracery: a central

The exterior decorative work covers the whole of the north and south gabled frontages and the faces of the north towers, in a dramatic scheme integral to the proportions of the building. The upper chamber over the main entrance has on both fronts a single tall arched window of pierced stone tracery: a central mullion

A mullion is a vertical element that forms a division between units of a window or screen, or is used decoratively. It is also often used as a division between double doors. When dividing adjacent window units its primary purpose is a rigid supp ...

branches to form two equal cusped ogee

An ogee ( ) is the name given to objects, elements, and curves—often seen in architecture and building trades—that have been variously described as serpentine-, extended S-, or sigmoid-shaped. Ogees consist of a "double curve", the combinatio ...

arches supporting a circular member in the head of the main window arch, intersected by a sigmoid curve in the north side and by a triskele

A triskelion or triskeles is an ancient motif consisting of a triple spiral exhibiting rotational symmetry.

The spiral design can be based on interlocking Archimedean spirals, or represent three bent human legs. It is found in artefacts of ...

device in the southern window. Externally this appears (on both fronts) as the central window in an arcade of three equal arches filling the breadth of the wall. The outer arches are executed in blind flushwork tracery: those of the north front both have a fourfold division of the upper circle, but with opposing or mirrored rotation. On the south front the flushwork tracery represents windows with paired mullions branching into a lattice of cusped quatrefoil

A quatrefoil (anciently caterfoil) is a decorative element consisting of a symmetrical shape which forms the overall outline of four partially overlapping circles of the same diameter. It is found in art, architecture, heraldry and traditional ...

s above. The tracery is reserved in freestone and infilled with carpets of neatly squared flints which shimmer in sunlight. Beneath this the south front has a shallow flushwork frieze of cusped arches or canopies with crocket

A crocket (or croquet) is a small, independent decorative element common in Gothic architecture. The name derives from the diminutive of the French ''croc'', meaning "hook", due to the resemblance of crockets to a bishop's crosier.

Description

...

ed pinnacles

A pinnacle is an architectural element originally forming the cap or crown of a buttress or small turret, but afterwards used on parapets at the corners of towers and in many other situations. The pinnacle looks like a small spire. It was main ...

, and in the gable above is the imitation of a rose window of wheel type.

The north towers beside the entrance also have blind tracery, and the two inner buttresses, which face forward, have niches to contain statues which are lost. A figure is shown in the west niche in Buck's engraving. These linked thematically with sculptures in the three niches set up in the north gable, the central figure there presumably being

The north towers beside the entrance also have blind tracery, and the two inner buttresses, which face forward, have niches to contain statues which are lost. A figure is shown in the west niche in Buck's engraving. These linked thematically with sculptures in the three niches set up in the north gable, the central figure there presumably being St Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

(to whom the priory was dedicated). Framed by this devotional tableau, the armorial display spreads across the whole width of wall above the entry archways. In five rows each of fourteen chequered squares, 35 shields of arms carved in high relief, with whimsical figures and grotesques

Since at least the 18th century (in French and German as well as English), grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, mysterious, magnificent, fantastic, hideous, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus ...

crowding into their surrounds, alternate with carved fleurs-de-lys

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in th ...

set into flushwork panels. Sir James Mann identified the upper row as showing (1) The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, (2) France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, (3) St Edmund's Bury, (4) Christ's Passion

In Christianity, the Passion (from the Latin verb ''patior, passus sum''; "to suffer, bear, endure", from which also "patience, patient", etc.) is the short final period in the life of Jesus Christ.

Depending on one's views, the "Passion" m ...

, (5) England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

(before it became quartered with France in 1340), (6) Léon and Castile, and (7) Hurtshelve. In the second and third rows are English baronial families and in the fourth and fifth are East Anglian gentry. The chequered arrangement is echoed in flushwork on the slanting sides of the adjacent towers, laid upright to the east and as lozenges to the west. Caröe noted the distinctively French carving of the string course

A belt course, also called a string course or sill course, is a continuous row or layer of stones or brick set in a wall. Set in line with window sills, it helps to make the horizontal line of the sills visually more prominent. Set between the ...

above the heraldry.

The final component of the decorative scheme occupied the space above the pedestrian arch, the lesser of the two entrance gates. In a field of flushwork tracery, a cinquefoil

''Potentilla'' is a genus containing over 300Guillén, A., et al. (2005)Reproductive biology of the Iberian species of ''Potentilla'' L. (Rosaceae).''Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid'' 1(62) 9–21. species of annual, biennial and perenn ...

surrounds a single carved presentation of the arms of Sir Guy Ferre the younger. Where these arms are recited in the Galloway Roll (c.1300) it is specified that they are for Guy Ferre "the nephew". The baton is for difference

Difference, The Difference, Differences or Differently may refer to:

Music

* ''Difference'' (album), by Dreamtale, 2005

* ''Differently'' (album), by Cassie Davis, 2009

** "Differently" (song), by Cassie Davis, 2009

* ''The Difference'' (al ...

from another Guy Ferre who bore the plain coat, and died probably in 1303.

The patron

Sir Guy Ferre the younger acquired the manor of Benhall with its patronage of Butley Priory and Leiston Abbey in or soon after 1290 (confirmed 1294), from Sir Nicholas de Crioll. He had trouble with poachers there in 1292. He had held this title (as from the

Sir Guy Ferre the younger acquired the manor of Benhall with its patronage of Butley Priory and Leiston Abbey in or soon after 1290 (confirmed 1294), from Sir Nicholas de Crioll. He had trouble with poachers there in 1292. He had held this title (as from the Honour of Eye

In the kingdom of England, a feudal barony or barony by tenure was the highest degree of feudal land tenure, namely ''per baroniam'' (Latin for "by barony"), under which the land-holder owed the service of being one of the king's barons. The ...

) for more than 10 years when de Crioll's death in 1303 prompted his widow Margery (daughter of Sir Gilbert Pecche (died 1291), patron of Barnwell Priory

Barnwell Priory was an Augustinians, Augustinian priory at Barnwell, Cambridgeshire, Barnwell in Cambridgeshire, founded as a house of Canons Regular. The only surviving parts are 13th-century claustral building, which is a Grade II* listed, and ...

), who remarried, to assert her right in dower, and she for herself and her heirs quitclaimed it to Sir Guy for £100 in 1304. Between 1292 and 1303 the priory asserted its rights in its benefice in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, the advowson of St Stephen, Coleman Street.

The early career of Sir Guy Ferre, which began in accompanying Prince Edmund to the Holy Land in 1271, and entering service in the household of the dowager Queen Eleanor of Provence

Eleanor of Provence (c. 1223 – 24/25 June 1291) was a French noblewoman who became Queen of England as the wife of King Henry III from 1236 until his death in 1272. She served as regent of England during the absence of her spouse in 1253.

...

, to whom he became steward and lastly executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

, is usually taken to refer to Sir Guy the elder. It is uncertain whether he, or the younger Sir Guy, was the ''magister'' to Prince Edward, or who in 1295 was "staying continually in the company of Edward the king's son by the king's special order." Guy the younger, who was not of English birth, was in Gascony with Edward I in 1286-89 while the king was reorganizing the administration of his Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine ( oc, Ducat d'Aquitània, ; french: Duché d'Aquitaine, ) was a historical fiefdom in western, central, and southern areas of present-day France to the south of the river Loire, although its extent, as well as its name, fluc ...

. Edward granted him the remainder of Gestingthorpe

Gestingthorpe (pronounced , 'guesstingthorpe') is a village and a civil parish in the Braintree district, in the English county of Essex. It is approximately halfway between the towns of Halstead in Essex and Sudbury in Suffolk. The nearest rail ...

, Essex, held by Gilbert Pecche, in 1289, and in 1298-99 he served as royal Lieutenant of the Duchy, with possession and use of its Seal. Following Edward II's accession, from March 1308 to September 1309 as Seneschal of Gascony he implemented mandates to resist Philip IV's subversion of English rule. At this time, Ascensiontide 1308, he associated his wife Elianore in the Benhall title, with named remainders in default of issue.

Sir Guy became a trusted ducal commissioner through the Process of Périgueux (a negotiation to end French encroachment in Gascony), though recalled for some months in 1312 to help release the king from the

Sir Guy became a trusted ducal commissioner through the Process of Périgueux (a negotiation to end French encroachment in Gascony), though recalled for some months in 1312 to help release the king from the Ordinances of 1311

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power of the English monarch. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the Lo ...

. Following the murder of the Seneschal John Ferrers in late 1312 Ferre was instructed to remain in Gascony to invest and assist his successor. A year later he returned to England, apparently for three years. Gilbert Pecche, Margery de Crioll's half-brother, was Seneschal in Gascony when, in 1317, Ferre was sent to John of Brittany

John of Brittany (french: Jean de Bretagne; c. 1266 – 17 January 1334), 4th Earl of Richmond, was an English nobleman and a member of the Ducal house of Brittany, the House of Dreux. He entered royal service in England under his uncle Ed ...

, king's Lieutenant in Gascony, then negotiating for the ransom of Aymer de Valence

Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (c. 127523 June 1324) was an Anglo-French nobleman. Though primarily active in England, he also had strong connections with the French royal house. One of the wealthiest and most powerful men of his age, ...

. In 1320 he was bidden to assume a place in the royal retinue at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

, where Edward paid liege homage

Homage (from Medieval Latin , lit. "pertaining to a man") in the Middle Ages was the ceremony in which a feudal tenant or vassal pledged reverence and submission to his feudal lord, receiving in exchange the symbolic title to his new position (inv ...

to Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was ...

for the Duchy of Aquitaine.

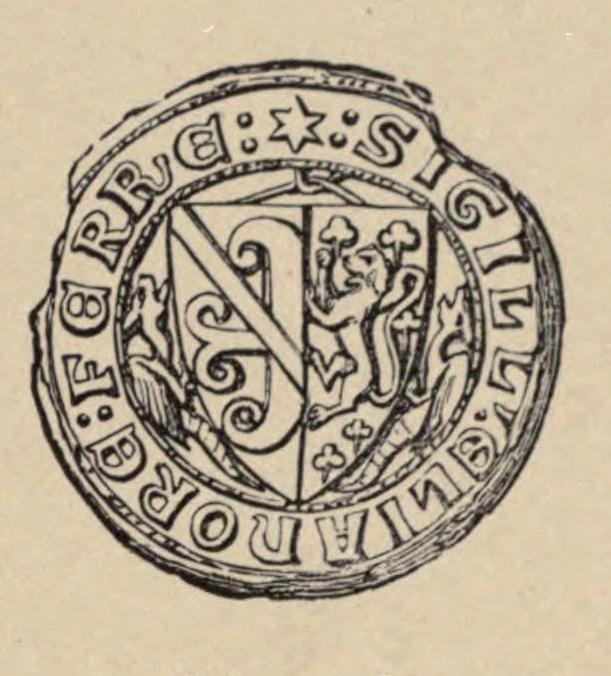

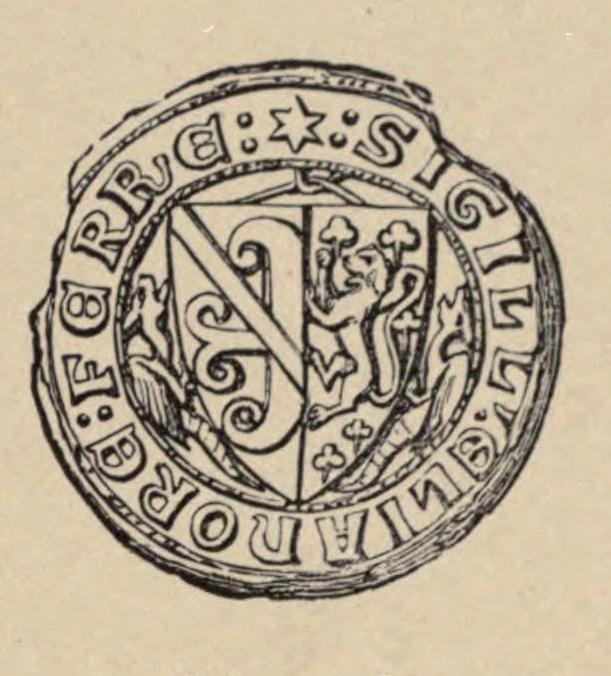

Sir Guy died without heir male in 1323 and (as stipulated in the 1289 grant of Gestingthorpe) his manors, except his entails of 1308, passed by reversion or escheat. But as Elianore Ferre held Benhall with him jointly, it remained wholly to her for her life under the Honour of Eye. An example of her personal seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impr ...

survives, attached to a document issued from Benhall in 1348. Her name inscription surrounds a shield bearing arms of Guy Ferre the younger impaled with a coat blazon

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct the appropriate image. The verb ''to blazon'' means to create such a description. The vis ...

ed by Robert Glover for "Mountender", and by Charles Segoing (a French herald of the 17th century) for a family of the township of Montendre

Montendre () is a commune in the Charente-Maritime department in southwestern France.

Population

In 1972 Montendre absorbed the former communes Chardes and Vallet.

See also

*Communes of the Charente-Maritime department

The following is a lis ...

in the Saintonge

Saintonge may refer to:

*County of Saintonge, a historical province of France on the Atlantic coast

*Saintonge (region), a region of France corresponding to the historical province

Places

*Saint-Genis-de-Saintonge, a commune in the Charente-Mari ...

frontier of English Aquitaine. Two wyverns

A wyvern ( , sometimes spelled wivern) is a legendary winged dragon that has two legs.

The wyvern in its various forms is important in heraldry, frequently appearing as a mascot of schools and athletic teams (chiefly in the United States, Un ...

support the shield, as in the Butley armorials.

Priors and patrons, 1300-1483

Between 1290 and 1300 Prior Thomas strove to retain the priory's control of its house at West Somerton. Richard de Iakesle, Prior 1303-1307, seems to have been appointed directly by Bishop John Salmon (a commissioner in Gascony with Guy Ferre and John of Brittany), and two others served briefly after him. The canons' right of free election was tested with the appointment of William de Geytone as prior in 1311 by a negotiated agreement. In his time, in 1322, St Olave and St Stephen in the Jewry, the priory's London parish, was appropriated to the priory by Bishop Gravesend. A distinguished prior, Geytone presided (with John of Cheddington, Prior ofDunstable

Dunstable ( ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Bedfordshire, England, east of the Chiltern Hills, north of London. There are several steep chalk escarpments, most noticeable when approaching Dunstable from the ...

) at the Augustinian General Chapter in Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

in 1325. This was an important occasion on which the chapter's acts and ordinances were entirely reformed, and the role of the ''diffinitores'' in their governance was established. They also presided at Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district in Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver Cromwell was born there ...

in 1328. He governed Butley Priory for 21 years until his death in 1332: the stone indent of his memorial brass

A monumental brass is a type of engraved sepulchral memorial, which in the 13th century began to partially take the place of three-dimensional monuments and effigies carved in stone or wood. Made of hard latten or sheet brass, let into the paveme ...

, with a crocketed canopy, is preserved in Hollesley

Hollesley is a village and civil parish in the East Suffolk district of Suffolk east of Ipswich in eastern England. Located on the Bawdsey peninsula five miles south-east of Woodbridge, in 2005 it had a population of 1,400 increasing to 1,581 ...

church, and shows him mitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in ...

d.

de Ufford patrons

The canons elected Alexander de Stratford to succeed, but he died a year later, and in his place they chose Matthew de Pakenham. Eleanor Ferre, whom they had not consulted, protested her rights to the canons and was forcefully resisted. She brought a petition against them but was referred to theCommon Law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

. John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

John of Eltham, 1st Earl of Cornwall (15 August 1316 – 13 September 1336) was the second son of Edward II of England and Isabella of France. He was heir presumptive to the English throne until the birth of his nephew Edward, the Black Princ ...

then held the reversion of Benhall (as of his Honour of Eye), and held it at his death in 1336. In 1337 King Edward III granted it to Robert de Ufford

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

upon his creation as 1st Earl of Suffolk. Eleanor Ferre retained her title to Benhall until her death in 1349, when the reversion to Robert de Ufford came into effect. His patronage of Leiston Abbey (as it had been held by de Crioll and de Ferre) was specifically confirmed in 1351. Matthew remained prior at Butley until his resignation in 1353.

Robert de Ufford, a de Pecche descendant, gave his attention to the rebuilding of Leiston Abbey

Leiston Abbey outside the town of Leiston, Suffolk, England, was a religious house of Canons Regular following the Premonstratensian rule (White canons), dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, St Mary. Founded in c. 1183 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 11 ...

on its present site. Through his mother, Cecily de Valoines, the de Ufford family interest centred especially upon Campsey Priory, where Robert and his son William de Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk

William Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk (30 May 1338 – 15 February 1382) was an English nobleman in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. He was the son of Robert Ufford, who was created Earl of Suffolk by Edward III in 1337. William had thre ...

were buried in 1369 and 1382 respectively. The Butley and Leiston patronage was then granted, with Benhall, by Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

to Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk

Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk, 1st Baron de la Pole, (c. 13305 September 1389) of Wingfield Castle in Suffolk, was an English financier and Lord Chancellor of England. His contemporary Froissart portrays de la Pole as a devious and in ...

, and after his fall in 1388 was regranted to Michael de la Pole the younger in 1398. Here Butley's right of free election of its prior seems to have expired. A tradition exists that the third Michael de la Pole, who fell at Agincourt in 1415, was buried in Butley priory church.

The period from 1374 to 1483 was, in any case, spanned by the long tenures of only three priors, William de Halesworth (1374-1410), William Randeworth (1410-1444) and William Poley (1444-1483). In 1398 the right was granted to the prior and his successors to use episcopal insignia, Mitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in ...

, ring and pastoral staff, by Papal privilege, and permissions to hold benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

s were granted to certain canons. William de Halesworth was a ''diffinitor'' at the Augustinian chapter at Northampton in 1404.

St Stephen Colman Street

Between 1430 and 1457 a concerted effort was made by wealthy London parishioners, apparently on behalf of theWorshipful Company of Leathersellers

The Worshipful Company of Leathersellers is one of the Livery company, livery companies of the City of London. The organisation originates from the latter part of the fourteenth century and received its Royal Charter in 1444, and is therefore t ...

, to detach the northern part of the priory's City parish of St Olave's and St Stephen in the Jewry to form a new parish centred upon St Stephen's (as many had long supposed it to be), and to deprive the priory of the endowments and advowson. This was supported in several judgements by the City authorities which Prior Randeworth was unable to resist. Prior Poley brought new energy to the cause. By his efforts, in 1457 the challenges to the priory's legitimate rights were overturned, and its authority in St Stephen's was confirmed, when the ecclesiastical authorities determined that the new parish ( St Stephen Coleman Street) should be constituted as a perpetual vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

age. It was incorporated formally by King Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

in 1466, who reformed its chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

to include daily prayers for Richard, Duke of York, Edmund, Earl of Rutland and Richard Nevill, Earl of Salisbury.

Through these events distrust arose between the priory and the parish. The 1457 judgement, which was arbitrated and decreed in person by Archbishop Bourchier, Thomas Kempe

Thomas Kempe was a medieval Bishop of London.

Kempe was the nephew of John Kemp

John Kemp ( – 22 March 1454, surname also spelled Kempe) was a medieval English cardinal, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor of England.

...

Bishop of London, William Waynflete

William Waynflete (11 August 1486), born William Patten, was Provost of Eton College (1442–1447), Bishop of Winchester (1447–1486) and Lord Chancellor of England (1456–1460). He founded Magdalen College, Oxford and three subsidiary scho ...

Bishop of Winchester, Sir John Fortescue Chief Justice, and the doctors of both laws Robert Stillington

Robert Stillington (about 1405 – May 1491) was an English cleric and administrator who was Bishop of Bath and Wells from 1465 and twice served as Lord Chancellor under King Edward IV. In 1483 he was instrumental in the accession of King Richa ...

and John Druell (prebendary and treasurer of St Paul's), bound both the priory and the parish representatives to desist from further dispute. Butley retained its rights in St Olave's and St Stephen's (rooted in the Diceto grant and the de Ardern fee), now as separate parishes, until the Dissolution. William Leek as vicar of St Stephen's was dynamic in reforming the parish from 1459 to 1478, and the church was favoured by prominent early Tudor merchants, not least the Mayor Thomas Bradbury (died 1510). Richard Kettyll, the priory's last presentation (appointed in 1530), saw the parish into the age of Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

and died in 1562.

The Tudor priory

The community

The last 50 years of the priory are unusually well-documented. The names of the canons themselves, and their observations and complaints about the management of the convent, can be followed in a series of Visitations by the Bishops of Norwich, commencing in 1492 with that of Bishop

The last 50 years of the priory are unusually well-documented. The names of the canons themselves, and their observations and complaints about the management of the convent, can be followed in a series of Visitations by the Bishops of Norwich, commencing in 1492 with that of Bishop James Goldwell

James Goldwell (died 15 February 1499) was a medieval Dean of Salisbury and Bishop of Norwich.

Life

Goldwell was one of the sons of William and Avice Goldwell, both of whom died in 1485. He had a brother, Nicholas Goldwell, who survived him. H ...

. Thomas Fram(l)yngham (1483-1503) was then prior, with 14 canons. Framyngham ruled at his own pleasure, and was given to entertaining his wealthy friends and relatives. Between this inspection and the next, by Bishop Richard Nykke

Richard Nykke (or Nix or Nick; c. 1447–1535) became bishop of Norwich under Pope Alexander VI in 1515. Norwich at this time was the second-largest conurbation in England, after London.

Nykke is often called the last Catholic bishop of the ...

in 1514, there were various developments. Edmund Lychefeld, Bishop of Chalcedon

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

(a titular see