Burnham Park (Chicago) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Burnham Park is a public

McFetridge Drive is the boundary between Grant Park and Burnham Park. Beginning with

McFetridge Drive is the boundary between Grant Park and Burnham Park. Beginning with

Ward fought for the poor people's access to Chicago's lakefront. In 1906, he campaigned to preserve neighboring Grant Park as a public park. Grant Park has been protected since 1836 by "forever open, clear and free" legislation that has been affirmed by four previous

Ward fought for the poor people's access to Chicago's lakefront. In 1906, he campaigned to preserve neighboring Grant Park as a public park. Grant Park has been protected since 1836 by "forever open, clear and free" legislation that has been affirmed by four previous

Cornell lobbied for the establishment of the South Parks and Boulevard System. The first bond vote was rejected in 1867, as just a method to provide remote driving grounds for rich citizens and to lure people to move away for the benefit of

Cornell lobbied for the establishment of the South Parks and Boulevard System. The first bond vote was rejected in 1867, as just a method to provide remote driving grounds for rich citizens and to lure people to move away for the benefit of

The Columbian Exposition was held in Jackson Park, leaving housing in Hyde Park built for the Fair. The area around the new

The Columbian Exposition was held in Jackson Park, leaving housing in Hyde Park built for the Fair. The area around the new

A $2.5 million bond issue passed in 1922 for a

A $2.5 million bond issue passed in 1922 for a

One highlight of the 1933

One highlight of the 1933

Chicago Park District Lakefront Trail Map

{{good article Parks in Chicago Beaches of Cook County, Illinois South Side, Chicago Century of Progress Urban public parks Works Progress Administration in Illinois World's fair sites in Illinois 1920 establishments in Illinois Protected areas established in 1920

park

A park is an area of natural, semi-natural or planted space set aside for human enjoyment and recreation or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats. Urban parks are urban green space, green spaces set aside for recreation inside t ...

located in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

. Situated along of Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

shoreline, the park connects Grant Park at 14th Street to Jackson Park at 56th Street. The of parkland is owned and managed by Chicago Park District

The Chicago Park District is one of the oldest and the largest park districts in the United States. As of 2016, there are over 600 parks included in the Chicago Park District as well as 27 beaches, several boat harbors, two botanic conservatories ...

.Graf, John, ''Chicago's Parks'' Arcadia Publishing, 2000, p. 63., . It was named for urban planner

An urban planner (also known as town planner) is a professional who practices in the field of town planning, urban planning or city planning.

An urban planner may focus on a specific area of practice and have a title such as city planner, town ...

and architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the '' Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been, "the most successful power broker the American architectural profession has ...

in 1927. Burnham was one of the designer

A designer is a person who plans the form or structure of something before it is made, by preparing drawings or plans.

In practice, anyone who creates tangible or intangible objects, products, processes, laws, games, graphics, services, or exp ...

s of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

.

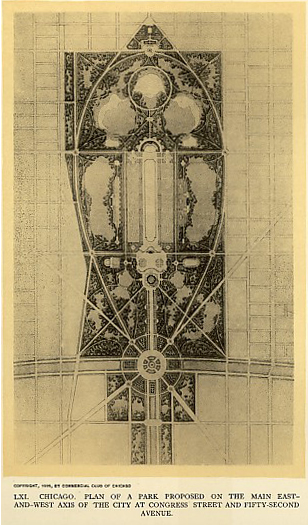

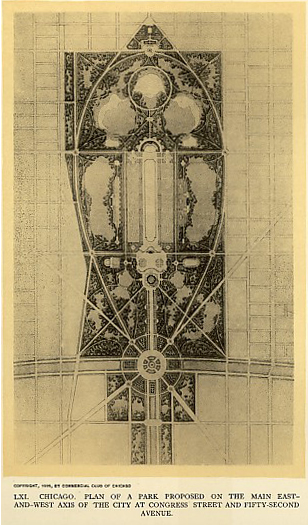

The park is an outgrowth of the 1909 Plan for Chicago

The Burnham Plan is a popular name for the 1909 ''Plan of Chicago'', co-authored by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett and published in 1909. It recommended an integrated series of projects including new and widened streets, parks, new railr ...

developed by the park's namesake Daniel Burnham and often called simply "The Burnham Plan". Land for the park has been acquired by the city's park district by a variety of means such as bequest, landfill, and barter. Now, the park hosts some of the city's most important municipal structures, such as Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

and McCormick Place

McCormick Place is the largest convention center in North America. It consists of four interconnected buildings and one indoor arena sited on and near the shore of Lake Michigan, about south of downtown Chicago, Illinois, United States. McCor ...

. The park has surrendered the land for the Museum Campus

Museum Campus is a park in Chicago that sits alongside Lake Michigan in Grant Park and encompasses five of the city's most notable attractions: the Adler Planetarium, America's first planetarium; the Shedd Aquarium; the Field Museum of Natura ...

to Grant Park. During the presidency of U.S. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

, the park was the landing site for Marine One

Marine One is the call sign of any United States Marine Corps aircraft carrying the president of the United States. It usually denotes a helicopter operated by Marine Helicopter Squadron One ( HMX-1) "Nighthawks", consisting of either the larg ...

when visiting his Kenwood home on Chicago's south side.

In the early 20th century, Chicago businessman A. Montgomery Ward advocated that the lakefront must be publicly accessible, and remain "forever open, clear and free", lest the city descend into the squalor typical of American cities of the time, with buildings and heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

destroying any chance for beauty. Ward's influence lead to the protection of the lake shore parks system and to this day, the city's lakefront is open from the former city limits at Hollywood Ave (5700N) down to the former steel mills near Rainbow Beach

Rainbow Beach is a coastal rural town and locality in the Gympie Region, Queensland, Australia. In the , Rainbow Beach had a population of 1,249 people.

It is a popular tourist destination, both in its own right and as a gateway to Fraser Islan ...

(7700S).

Location

Northerly Island

Northerly Island is a man-made peninsula along Chicago's Lake Michigan lakefront. The site of the Adler Planetarium, Northerly Island connects to the mainland through a narrow isthmus along Solidarity Drive. This street is dominated by Neoclass ...

and the 14th Street Beach, and enclosing Burnham Harbor and its public marina

A marina (from Spanish , Portuguese and Italian : ''marina'', "coast" or "shore") is a dock or basin with moorings and supplies for yachts and small boats.

A marina differs from a port in that a marina does not handle large passenger ships o ...

, the park runs in a narrow strip past Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

and McCormick Place

McCormick Place is the largest convention center in North America. It consists of four interconnected buildings and one indoor arena sited on and near the shore of Lake Michigan, about south of downtown Chicago, Illinois, United States. McCor ...

, both of which disrupt Burnham's original plan, south to 56th street. From North to South, the park runs through the communities of Near South, Douglas

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

*Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil W ...

, Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay A ...

, Kenwood and Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

.

The park lies mostly between Lake Shore Drive

Lake Shore Drive (officially Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable Lake Shore Drive, and called DuSable Lake Shore Drive, The Outer Drive, The Drive, or LSD) is a multilevel expressway that runs alongside the shoreline of Lake Michigan, and adjacent to ...

and Lake Michigan, but it crosses the drive and abuts the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also co ...

tracks in places. There is a beach at 31st Street, a skatepark

A skatepark, or skate park, is a purpose-built recreational environment made for skateboarding, BMX, scootering, wheelchairs, and aggressive inline skating. A skatepark may contain half-pipes, handrails, funboxes, vert ramps, stairsets, q ...

at 34th Street, a stone beach at 49th Street, and a model boat pond at 51st Street in Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

. The park ends with a flourish at Promontory Point at 55th Street. Footbridges and underpasses provide access to the park over the barriers of the train tracks and Lake Shore Drive. A section of the Chicago Lakefront Trail

The Chicago Lakefront Trail (LFT) is a partial shared use path for walking, jogging, skateboarding, and cycling, located along the western shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago, Illinois. The trail passes through and connects Chicago's four major la ...

bicycle and jogging path runs the length of the park.

History

Ward fought for the poor people's access to Chicago's lakefront. In 1906, he campaigned to preserve neighboring Grant Park as a public park. Grant Park has been protected since 1836 by "forever open, clear and free" legislation that has been affirmed by four previous

Ward fought for the poor people's access to Chicago's lakefront. In 1906, he campaigned to preserve neighboring Grant Park as a public park. Grant Park has been protected since 1836 by "forever open, clear and free" legislation that has been affirmed by four previous Illinois Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Illinois is the state supreme court, the highest court of the State of Illinois. The court's authority is granted in Article VI of the current Illinois Constitution, which provides for seven justices elected from the five ap ...

rulings. In the mid-1890s, architect Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the '' Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been, "the most successful power broker the American architectural profession has ...

began planning a park and boulevard that would link Jackson Park with Grant Park and downtown. As Chief of Construction for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Burnham was known for developing the White City. After the fair, Burnham began designing a more functional Chicago. Burnham's plan, including a lakefront park with a series of islands, boating harbor, beaches, and playfields was published in his 1909 Plan of Chicago

The Burnham Plan is a popular name for the 1909 ''Plan of Chicago'', co-authored by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett and published in 1909. It recommended an integrated series of projects including new and widened streets, parks, new railr ...

. Burnham's famous 1909 plan eventually preserved Grant Park and the entire Chicago lakefront.

1860-1890

Paul Cornell

Paul Douglas Cornell (born 18 July 1967) is a British writer best known for his work in television drama as well as ''Doctor Who'' fiction, and as the creator of one of the Doctor's spin-off companions, Bernice Summerfield.

As well as ''Docto ...

, a lawyer and real estate developer, donated and built East End Park between 51st and 53rd Streets in 1856. After much of the land eroded, the property was incorporated into Burnham Park and was eventually renamed Harold Washington Park

Harold Washington Park is a small (10 acre) park in the Chicago Park District located in the Hyde Park community area on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, US. In 1992, it was named for Harold Washington (1922–1987), the first African-Amer ...

in 1992. In the years following his donation, expansions were built at the northeast corner of the future Jackson Park, located at the south end of Burnham. The most notable expansions included a seawall and granite paved strolling beach, constructed from 1884 to 1888, and a building used as the Iowa Pavilion during the Columbian Exposition.

Cornell lobbied for the establishment of the South Parks and Boulevard System. The first bond vote was rejected in 1867, as just a method to provide remote driving grounds for rich citizens and to lure people to move away for the benefit of

Cornell lobbied for the establishment of the South Parks and Boulevard System. The first bond vote was rejected in 1867, as just a method to provide remote driving grounds for rich citizens and to lure people to move away for the benefit of real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more general ...

speculators and developers. In 1869, the bills were passed by the legislature, and the South Park Commission was formed with support from Cornell. The future site was primarily under Lake Michigan or abutting the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also co ...

right of way. In 1892, the formerly trestled railroad was raised on an embankment

Embankment may refer to:

Geology and geography

* A levee, an artificial bank raised above the immediately surrounding land to redirect or prevent flooding by a river, lake or sea

* Embankment (earthworks), a raised bank to carry a road, railwa ...

, along the present west edge of the park. South Park (the present Jackson Park) was slowly developed, and along with the Midway Plaisance

The Midway Plaisance, known locally as the Midway, is a public park on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is one mile long by 220 yards wide and extends along 59th and 60th streets, joining Washington Park at its west end and Jackson Park ...

and Washington Park, the designs by Frederick Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co ...

and Calvert Vaux

Calvert Vaux (; December 20, 1824 – November 19, 1895) was an English-American architect and landscape designer, best known as the co-designer, along with his protégé and junior partner Frederick Law Olmsted, of what would become New York Ci ...

were focused on lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') a ...

s and navigation from the Lake to South Park Way (now King Dr.) and 55th Street, in addition to the development of a country driving park, horse and buggy

]

A horse and buggy (in American English) or horse and carriage (in British English and American English) refers to a light, simple, two-person carriage of the late 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, drawn usually by one or sometimes by two ho ...

paths along the lake, and a water system running north to downtown. By the 1880s, the development included the Kenwood and Bowen communities, and by the 1890s, immigrant

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

neighborhoods were developing. The city limits were expanded from 39th to 130th in 1889, absorbing virtually all of Hyde Park Township (35th to 138th).

1890-1910

The Columbian Exposition was held in Jackson Park, leaving housing in Hyde Park built for the Fair. The area around the new

The Columbian Exposition was held in Jackson Park, leaving housing in Hyde Park built for the Fair. The area around the new University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

allowed real estate developers an opportunity to profit during the depression of the mid-1890s. As part of Jackson Park's transformation, South Park Commission President James E. Ellsworth asked Burnham to design a boulevard linking Jackson and Grant Parks. Ruling out residential expansion, Burnham developed plans for green areas, harbors

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

and lagoons, water scenery, a canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

to downtown, and a scenic drive. With a theme of a "playground for the people", the area was planned to include bridges, beaches with pavilions, and bathing houses. In 1896, Burnham began marketing the plan to Marshall Field

Marshall Field (August 18, 1834January 16, 1906) was an American entrepreneur and the founder of Marshall Field and Company, the Chicago-based department stores. His business was renowned for its then-exceptional level of quality and customer ...

, George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car and founded a company town, Pullman, for the workers who manufactured it. This ulti ...

, Philip Armour

Philip Danforth Armour Sr. (16 May 1832 – 6 January 1901) was an American meatpacking industrialist who founded the Chicago-based firm of Armour & Company. Born on an upstate New York farm, he made $8,000 in the California gold rush, 1852 ...

, and business organizations. In 1901, the Chicago Commercial Club began promoting the ideas and in 1909, published the Plan of Chicago

The Burnham Plan is a popular name for the 1909 ''Plan of Chicago'', co-authored by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett and published in 1909. It recommended an integrated series of projects including new and widened streets, parks, new railr ...

by Burnham and Edward H. Bennett

Edward Herbert Bennett (1874–1954) was an architect and city planner best known for his co-authorship of the 1909 Plan of Chicago.

Biography

Bennett was born in Bristol, England in 1874, and later moved to San Francisco with his family.Cohen, 2 ...

and illustrated by Jules Guerin

Jules is the French form of the Latin "Julius" (e.g. Jules César, the French name for Julius Caesar). It is the given name of:

People with the name

*Jules Aarons (1921–2008), American space physicist and photographer

*Jules Abadie (1876–195 ...

. From 1907 until 1920, legal battles to acquire parkland continued despite the 1907 Legislature passing a bill with language favoring railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s until courts rejected the legislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolled bill, enrolling, enactment of a bill, enacting, or promulgation, promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous Government, governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law i ...

.

1910-1920

The South Park Commission received rights to the future site of the Field Museum in exchange for transferred to the Illinois Central Railroad. Government agencies had to agree to plans, including theCook County Circuit Court

The Circuit Court of Cook County is the largest of the 24 judicial circuits in Illinois as well as one of the largest unified court systems in the United States — second only in size to the Superior Court of Los Angeles County since that court ...

, General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

, Chicago Plan Commission

The Chicago Plan Commission is a commission implemented to promote the ''Plan of Chicago,'' often called the Burnham Plan. After official presentation of the Plan to the city on July 6, 1909, the City Council of Chicago authorized Mayor Fred A. Bu ...

, and U.S. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of th ...

. In 1912, Burnham died and a new Chicago Plan Commission was created. In 1919, landfill efforts began at the north end of the park. In February 1920, voters approved a $20 million bond issue as part of the Burnham Plan initiative for new lands to complete Grant Park, so as to create the South Shore Development. In 1920, the Field Museum was opened, with the exhibits moved from Jackson Park into the basement. By 1925, new landforms, including Northerly Island, the only offshore landform in the Burnham Plan

The Burnham Plan is a popular name for the 1909 ''Plan of Chicago'', co-authored by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett and published in 1909. It recommended an integrated series of projects including new and widened streets, parks, new rail ...

actually built, were completed to 23rd Street.

1920-1930

A $2.5 million bond issue passed in 1922 for a

A $2.5 million bond issue passed in 1922 for a stadium

A stadium ( : stadiums or stadia) is a place or venue for (mostly) outdoor sports, concerts, or other events and consists of a field or stage either partly or completely surrounded by a tiered structure designed to allow spectators to stand o ...

conceived by Burnham. Designed by architects Holabird & Roche

The architectural firm now known as Holabird & Root was founded in Chicago in 1880. Over the years, the firm has changed its name several times and adapted to the architectural style then current — from Chicago School to Art Deco to Modern ...

and named Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

for the veterans of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, cost overruns required another bond issue

In finance, a bond is a type of security under which the issuer (debtor) owes the holder (creditor) a debt, and is obliged – depending on the terms – to repay the principal (i.e. amount borrowed) of the bond at the maturity date as well as i ...

in 1926. By 1924, the breakwater

Breakwater may refer to:

* Breakwater (structure), a structure for protecting a beach or harbour

Places

* Breakwater, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria, Australia

* Breakwater Island

Breakwater Island () is a small island in the Palme ...

wall stretched from 14th to 55th Streets. In 1926, Soldier Field and a portion of Lake Shore Drive

Lake Shore Drive (officially Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable Lake Shore Drive, and called DuSable Lake Shore Drive, The Outer Drive, The Drive, or LSD) is a multilevel expressway that runs alongside the shoreline of Lake Michigan, and adjacent to ...

were opened. Landfill

A landfill site, also known as a tip, dump, rubbish dump, garbage dump, or dumping ground, is a site for the disposal of waste materials. Landfill is the oldest and most common form of waste disposal, although the systematic burial of the waste ...

ing extended from 23rd Street to 56th Street; however, Promontory Point was not complete, prompting complaints regarding garbage, blowing sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class of s ...

and odors. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, landfill efforts continued to fill in Burnham Park and the adjacent Northerly Island. The South Development was named for Daniel Burnham on January 14, 1927, and support increased for a world's fair in the park. Construction was completed on Lake Shore Drive, with northbound lanes named for Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson, Leiv Eiriksson, or Leif Ericson, ; Modern Icelandic: ; Norwegian: ''Leiv Eiriksson'' also known as Leif the Lucky (), was a Norse explorer who is thought to have been the first European to have set foot on continental North ...

, and southbound lanes for Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

. In 1929, construction of the park at Promontory Point began. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

delayed work and prevented construction of nearshore islands. Burnham Park was chosen for the site of the Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

world's fair and a yacht basin was built south of 51st Street.

1930s-1940s

In 1933 and 1934, theCentury of Progress International Exposition

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositio ...

was held in Burnham Park. In the mid-1930s, the Chicago Park District

The Chicago Park District is one of the oldest and the largest park districts in the United States. As of 2016, there are over 600 parks included in the Chicago Park District as well as 27 beaches, several boat harbors, two botanic conservatories ...

used funds from the federal Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

to complete landfill operations and install landscaping

Landscaping refers to any activity that modifies the visible features of an area of land, including the following:

# Living elements, such as flora or fauna; or what is commonly called gardening, the art and craft of growing plants with a goal o ...

at Promontory Point by renowned designer Alfred Caldwell

Alfred Caldwell (May 26, 1903 – July 3, 1998) was an American architect best known for his landscape architecture in and around Chicago, Illinois.

Family and education

Caldwell and his wife Virginia had a daughter, Carol Caldwell Dooley, born ...

, a professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology

Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the merger of the Armour Institute and Lewis Institute in 1940. The university has prog ...

. In 1935, Mayor Edward Joseph Kelly

Edward Joseph Kelly (May 1, 1876October 20, 1950) was an American politician who served as the 46th Mayor of Chicago from April 17, 1933 until April 15, 1947.

Prior to being mayor of Chicago, Kelly served as chief engineer of the Chicago Sani ...

explored the idea of a permanent fair in the park. The state passed a bill creating the Metropolitan Fair and Exposition Authority and allowed construction of Meigs Field

Merrill C. Meigs Field Airport (pronounced , formerly ) was a single-runway airport in Chicago that was in operation from December 1948 until March 2003 on Northerly Island, an artificial peninsula on Lake Michigan. The airport sat adjacent to ...

, after Northerly Island lost out as the site for the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

. In 1948, Burnham Park hosted the Chicago Railroad Fair

The Chicago Railroad Fair was an event organized to celebrate and commemorate 100 years of railroad history west of Chicago, Illinois. It was held in Chicago in 1948 and 1949 along the shore of Lake Michigan and is often referred to as "the last ...

, proving the location's viability for conventions, which eventually led to the construction of the first McCormick Place

McCormick Place is the largest convention center in North America. It consists of four interconnected buildings and one indoor arena sited on and near the shore of Lake Michigan, about south of downtown Chicago, Illinois, United States. McCor ...

in 1960.

Balbo Monument

One highlight of the 1933

One highlight of the 1933 Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

World's Fair was popular Italian aviator

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its Aircraft flight control system, directional flight controls. Some other aircrew, aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are al ...

and prominent fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa. Due to his young a ...

, leading 24 flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

s in landing on Lake Michigan after a transatlantic flight

A transatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe, Africa, South Asia, or the Middle East to North America, Central America, or South America, or ''vice versa''. Such flights have been made by fixed-wing air ...

from Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Balbo's squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

left Italy on June 30, 1933, and arrived on July 15, after making several short stops. To honor his journey, 7th Street was renamed Balbo Drive. As a return gift, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

sent an ancient 2nd-century Roman column, which was erected in front of the Italian pavilion during the Century of Progress Exposition. Located near the lakefront bike trail east of Soldier Field, the Balbo Monument

The Balbo Monument consists of a column that is approximately 2,000 years old dating from between 117 and 38 BC and a contemporary stone base. It was taken from an ancient port town outside of Rome by Benito Mussolini and given to the city of Chic ...

is one of the few relics remaining from the fair. The column is from a portico near the Porta Marina of Ostia Antica

Ostia Antica ("Ancient Ostia") is a large archaeological site, close to the modern town of Ostia (Rome), Ostia, that is the location of the harbour city of ancient Rome, 25 kilometres (15 miles) southwest of Rome. "Ostia" (plur. of "ostium") is a ...

and stands on a marble base with inscriptions in both Italian and English reading:

"This column, twenty centuries old, was erected on the beach of Ostia, the port of Imperial Rome, to watch over the fortunes and victories of the Romantriremes A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ....Fascist Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...Italy, with the sponsorship of Benito Mussolini, presents to Chicago a symbol and memorial in honor of the Atlantic Squadron led by Balbo, which with Roman daring, flew across the ocean in the 11th year of the Fascist era."

1950s-1970s

During the 1950s, the park was the host of aProject Nike

Project Nike (Greek: Νίκη, "Victory") was a U.S. Army project, proposed in May 1945 by Bell Laboratories, to develop a line-of-sight anti-aircraft missile system. The project delivered the United States' first operational anti-aircraft mi ...

air defense system missile site. The United States Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national secu ...

and the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

kept similar sites in 40 United States cities during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

and dismantled them in 1971. The original McCormick Place burned down in 1967, and despite opposition, a new facility opened in Burnham Park in 1971.

Burnham Park today

Facilities

TheMuseum Campus

Museum Campus is a park in Chicago that sits alongside Lake Michigan in Grant Park and encompasses five of the city's most notable attractions: the Adler Planetarium, America's first planetarium; the Shedd Aquarium; the Field Museum of Natura ...

, which includes the Adler Planetarium

The Adler Planetarium is a public museum in Chicago, Illinois, dedicated to astronomy and astrophysics. It was founded in 1930 by local businessman Max Adler. Located on the northeastern tip of Northerly Island on Lake Michigan in the city, t ...

, Shedd Aquarium

Shedd Aquarium (formally the John G. Shedd Aquarium) is an indoor public aquarium in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States. Opened on May 30, 1930, the aquarium was for some time the largest indoor facility in the world. Today it holds about ...

and Field Museum, was annexed to Grant Park from Burnham Park in the late 1990s. Burnham Park's still contain Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

and Chicago's premier convention center, McCormick Place

McCormick Place is the largest convention center in North America. It consists of four interconnected buildings and one indoor arena sited on and near the shore of Lake Michigan, about south of downtown Chicago, Illinois, United States. McCor ...

-on-the-Lake, which hosts more than four million people per year. The Chicago Park District maintains several beaches and also operates a all-concrete skatepark

A skatepark, or skate park, is a purpose-built recreational environment made for skateboarding, BMX, scootering, wheelchairs, and aggressive inline skating. A skatepark may contain half-pipes, handrails, funboxes, vert ramps, stairsets, q ...

, just south of the 31st Street Beachhouse. It has been widely reported that when U.S. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

returns to visit his Chicago home in the Kenwood community area, he is transported by helicopter from O'Hare International Airport

Chicago O'Hare International Airport , sometimes referred to as, Chicago O'Hare, or simply O'Hare, is the main international airport serving Chicago, Illinois, located on the city's Northwest Side, approximately northwest of the Chicago Loop, ...

to Burnham Park, where he is transferred to his motorcade

A motorcade, or autocade, is a procession of vehicles.

Etymology

The term ''motorcade'' was coined by Lyle Abbot (in 1912 or 1913 when he was automobile editor of the ''Arizona Republican''), and is formed after ''cavalcade'', playing off of ...

.

Harbors and marinas

The park includes two harbors for the docking of fishing and leisure craft. Located adjacent to the Museum Campus andSoldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

, Burnham Harbor is created by Northerly Island

Northerly Island is a man-made peninsula along Chicago's Lake Michigan lakefront. The site of the Adler Planetarium, Northerly Island connects to the mainland through a narrow isthmus along Solidarity Drive. This street is dominated by Neoclass ...

. It contains 1120 docking facilities, a harbor store, a boat ramp, and the Burnham Park Yacht Club. The 31st Street Harbor, adjacent to the 31st Street Beach, opened in 2012. It contains 1000 floating slips, a harbor store, and a boat ramp. It also provides new park amenities.

Morgan Shoal

In 1999, the Park District initiated a long-range planning program for a number of lakefront and historic parks. On January 5, 2000, the Park District made its first move towards adding acreage to the park by adopting the Burnham Park Framework Plan. The project, which as of 2009 was still continuing, is a joint commission of the Park District, theU.S. Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

, and the City of Chicago Department of Environment. The project has been delayed in part because the Corps of Engineers has been diverted to design projects for the Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق (Kurdish languages, Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict (2003–present), I ...

. In conjunction with Harza Engineering, BauerLatoza Studio designed a nature area within a portion of the park between 45th and 51st Streets, featuring the shallow bedrock in an area known as Morgan Shoal. The $42 million expansion will increase parkland by , filling Lake Michigan.

Chicago Lakefront Trail

TheChicago Lakefront Trail

The Chicago Lakefront Trail (LFT) is a partial shared use path for walking, jogging, skateboarding, and cycling, located along the western shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago, Illinois. The trail passes through and connects Chicago's four major la ...

(LFT) is an multi-use path

A shared-use path, mixed-use path or multi-use pathway is a path which is 'designed to accommodate the movement of pedestrians and cyclists'. Examples of shared-use paths include sidewalks designated as shared-use, bridleways and rail trails. A ...

along Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

's shoreline. It is popular with cyclists and joggers. From north to south, it runs through Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park is a park along Lake Michigan on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. Named after US President Abraham Lincoln, it is the city's largest public park and stretches for seven miles (11 km) from Grand Avenue (500 N), on the south, ...

, Grant Park, Burnham Park, and Jackson Park.

See also

*Parks in Chicago

Parks in Chicago include open spaces and facilities, developed and managed by the Chicago Park District. The City of Chicago devotes 8.5% of its total land acreage to parkland, which ranked it 13th among high-density population cities in the Unit ...

*'' Powers of Ten'', a 1977 short film by Charles and Ray Eames

Charles Eames ( Charles Eames, Jr) and Ray Eames ( Ray-Bernice Eames) were an American married couple of industrial designers who made significant historical contributions to the development of modern architecture and furniture through the work of ...

that illustrates the concept of orders of magnitude

An order of magnitude is an approximation of the logarithm of a value relative to some contextually understood reference value, usually 10, interpreted as the base of the logarithm and the representative of values of magnitude one. Logarithmic dis ...

using a couple picnicking in Burnham Park.

Notes

External links

*Chicago Park District Lakefront Trail Map

{{good article Parks in Chicago Beaches of Cook County, Illinois South Side, Chicago Century of Progress Urban public parks Works Progress Administration in Illinois World's fair sites in Illinois 1920 establishments in Illinois Protected areas established in 1920