Burke And Wills on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Burke and Wills expedition was organised by the

The Burke and Wills expedition was organised by the

In 1857 the Philosophical Institute formed an ''Exploration Committee'' with the aim of investigating the practicability of fitting out an exploring expedition. While interest in inland exploration was strong in the neighbouring colonies of

In 1857 the Philosophical Institute formed an ''Exploration Committee'' with the aim of investigating the practicability of fitting out an exploring expedition. While interest in inland exploration was strong in the neighbouring colonies of

The Victorian Exploration Committee gave Burke written instructions. These included suggestions for the route to take but also gave Burke discretion depending on conditions and barriers he might encounter. The instructions were signed by the Honorary Secretary Dr John Macadam and in part advised:

The Victorian Exploration Committee gave Burke written instructions. These included suggestions for the route to take but also gave Burke discretion depending on conditions and barriers he might encounter. The instructions were signed by the Honorary Secretary Dr John Macadam and in part advised:

The expedition set off from

The expedition set off from  The expedition reached

The expedition reached

In 1860 Cooper Creek was the outer limit of the land that had been explored by Europeans, the river having been visited by Captain Charles Sturt in 1845 and

In 1860 Cooper Creek was the outer limit of the land that had been explored by Europeans, the river having been visited by Captain Charles Sturt in 1845 and

On their way north, the weather had been hot and dry, but on the way back the

On their way north, the weather had been hot and dry, but on the way back the

Burke had asked Brahe and the depot party to remain at the camp on the Cooper for 13 weeks. The party had actually waited for 18 weeks and was running low on supplies and starting to feel the effects of scurvy; they had come to believe that Burke would never return from the Gulf. After one of his men had injured his leg, Brahe decided to return to Menindee, but before leaving buried some provisions in case Burke did return, and blazed (cut or carved) a message on a tree to mark the spot.

Brahe left the depot on Cooper Creek on the morning of Sunday, 21 April 1861. Burke, Wills and King returned that evening. Finding the camp deserted, they dug up the cache of supplies, and a letter explaining that the party had given up waiting and had left. Burke's team had missed them by only nine hours. The three men and two remaining camels were exhausted; they had no hope of catching up to the main party.

Burke had asked Brahe and the depot party to remain at the camp on the Cooper for 13 weeks. The party had actually waited for 18 weeks and was running low on supplies and starting to feel the effects of scurvy; they had come to believe that Burke would never return from the Gulf. After one of his men had injured his leg, Brahe decided to return to Menindee, but before leaving buried some provisions in case Burke did return, and blazed (cut or carved) a message on a tree to mark the spot.

Brahe left the depot on Cooper Creek on the morning of Sunday, 21 April 1861. Burke, Wills and King returned that evening. Finding the camp deserted, they dug up the cache of supplies, and a letter explaining that the party had given up waiting and had left. Burke's team had missed them by only nine hours. The three men and two remaining camels were exhausted; they had no hope of catching up to the main party.

They decided to rest and recuperate, living off the supplies left in the cache. Wills and King wanted to follow their outward track back to Menindee, but Burke overruled them and decided to attempt to reach the furthest outpost of pastoral settlement in

They decided to rest and recuperate, living off the supplies left in the cache. Wills and King wanted to follow their outward track back to Menindee, but Burke overruled them and decided to attempt to reach the furthest outpost of pastoral settlement in

Brahe blazed two trees () at Depot Camp LXV on the banks of Bullah Bullah Waterhole on

Brahe blazed two trees () at Depot Camp LXV on the banks of Bullah Bullah Waterhole on

Towards the end of June 1861 as the three men were following the Cooper upstream to find the Yandruwandha campsite, Wills became too weak to continue. He was left behind at his own insistence at Breerily Waterhole with some food, water and shelter. Burke and King continued upstream for another two days until Burke became too weak to continue. The next morning Burke died. King stayed with his body for two days and then returned downstream to Breerily Waterhole, where he found that Wills had died as well.

The exact dates on which Burke and Wills died are unknown and different dates are given on various memorials in Victoria. The Exploration Committee fixed 28 June 1861 as the date both explorers died. King found a group of Yandruwandha willing to give him food and shelter and in return he shot birds to contribute to their supplies.

Towards the end of June 1861 as the three men were following the Cooper upstream to find the Yandruwandha campsite, Wills became too weak to continue. He was left behind at his own insistence at Breerily Waterhole with some food, water and shelter. Burke and King continued upstream for another two days until Burke became too weak to continue. The next morning Burke died. King stayed with his body for two days and then returned downstream to Breerily Waterhole, where he found that Wills had died as well.

The exact dates on which Burke and Wills died are unknown and different dates are given on various memorials in Victoria. The Exploration Committee fixed 28 June 1861 as the date both explorers died. King found a group of Yandruwandha willing to give him food and shelter and in return he shot birds to contribute to their supplies.

On 4 August 1861, HMVS ''Victoria'' under the Command of

On 4 August 1861, HMVS ''Victoria'' under the Command of

Frederick Walker led the Victorian Relief Expedition. The party, consisting of twelve mounted men, seven of them ex-troopers from the Native Police Corps, started from

Frederick Walker led the Victorian Relief Expedition. The party, consisting of twelve mounted men, seven of them ex-troopers from the Native Police Corps, started from

Unknown to the explorers, ''ngardu'' sporocarps contain the

Unknown to the explorers, ''ngardu'' sporocarps contain the

* 11 November 1860. Burke, Wills, King, Gray, Brahe, Mahomet, Patton and McDonough made their first camp on what they thought was Cooper Creek, but which was actually the Wilson River. This was Camp LVII (Camp 57).

* 20 November 1860. The first Depôt Camp was established at Camp LXIII (Camp 63).

* 6 December 1860. The Depôt Camp was moved downstream to Camp LXV—The Dig Tree (Camp 65).

* 16 December 1860. Burke, Wills, King and Gray left the Depôt for the Gulf of Carpentaria.

* 16 December 1860—21 April 1861. Brahe is left in charge of the Depôt at Cooper Creek.

* 21 April 1861. Brahe buried a cache of supplies, carved a message in the ''Dig Tree'' and headed back to Menindee. Later that day, Burke, Wills and King returned from the Gulf to find the Depôt deserted.

* 23 April 1861. Burke, Wills and King followed the Cooper downstream heading towards Mount Hopeless in South Australia.

* 7 May 1861. The last camel, Rajah, died. The men cannot carry enough supplies to leave the creek.

* 8 May 1861. Brahe and Wright return to the ''Dig Tree''. They stayed only 15 minutes and did not dig up Burke's note in the cache.

* 30 May 1861. Wills, having failed to reach Mount Hopeless, returned to the ''Dig Tree'' to bury his notebooks in the cache for safe-keeping.

* End of June/ early July 1861. Burke and Wills died.

* 11 September 1861. Howitt, leader of the ''Burke Relief Expedition'' arrived at the ''Dig Tree''.

* 15 September 1861. Howitt found King the only survivor of the four men who reached the Gulf.

* 28 September 1861. Howitt dug up the cache at the 'Dig Tree' and recovered Wills' notebooks.

* 11 November 1860. Burke, Wills, King, Gray, Brahe, Mahomet, Patton and McDonough made their first camp on what they thought was Cooper Creek, but which was actually the Wilson River. This was Camp LVII (Camp 57).

* 20 November 1860. The first Depôt Camp was established at Camp LXIII (Camp 63).

* 6 December 1860. The Depôt Camp was moved downstream to Camp LXV—The Dig Tree (Camp 65).

* 16 December 1860. Burke, Wills, King and Gray left the Depôt for the Gulf of Carpentaria.

* 16 December 1860—21 April 1861. Brahe is left in charge of the Depôt at Cooper Creek.

* 21 April 1861. Brahe buried a cache of supplies, carved a message in the ''Dig Tree'' and headed back to Menindee. Later that day, Burke, Wills and King returned from the Gulf to find the Depôt deserted.

* 23 April 1861. Burke, Wills and King followed the Cooper downstream heading towards Mount Hopeless in South Australia.

* 7 May 1861. The last camel, Rajah, died. The men cannot carry enough supplies to leave the creek.

* 8 May 1861. Brahe and Wright return to the ''Dig Tree''. They stayed only 15 minutes and did not dig up Burke's note in the cache.

* 30 May 1861. Wills, having failed to reach Mount Hopeless, returned to the ''Dig Tree'' to bury his notebooks in the cache for safe-keeping.

* End of June/ early July 1861. Burke and Wills died.

* 11 September 1861. Howitt, leader of the ''Burke Relief Expedition'' arrived at the ''Dig Tree''.

* 15 September 1861. Howitt found King the only survivor of the four men who reached the Gulf.

* 28 September 1861. Howitt dug up the cache at the 'Dig Tree' and recovered Wills' notebooks.

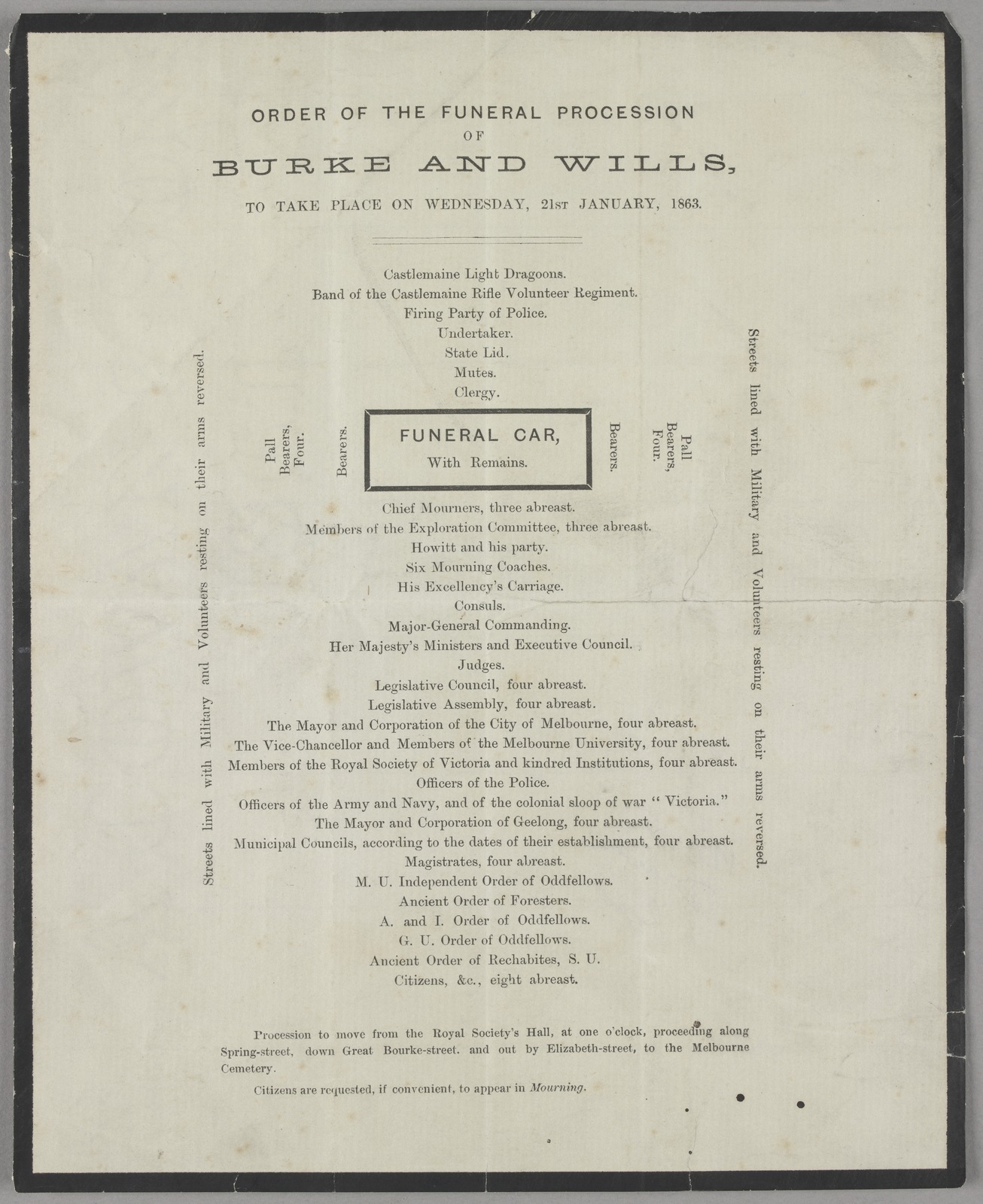

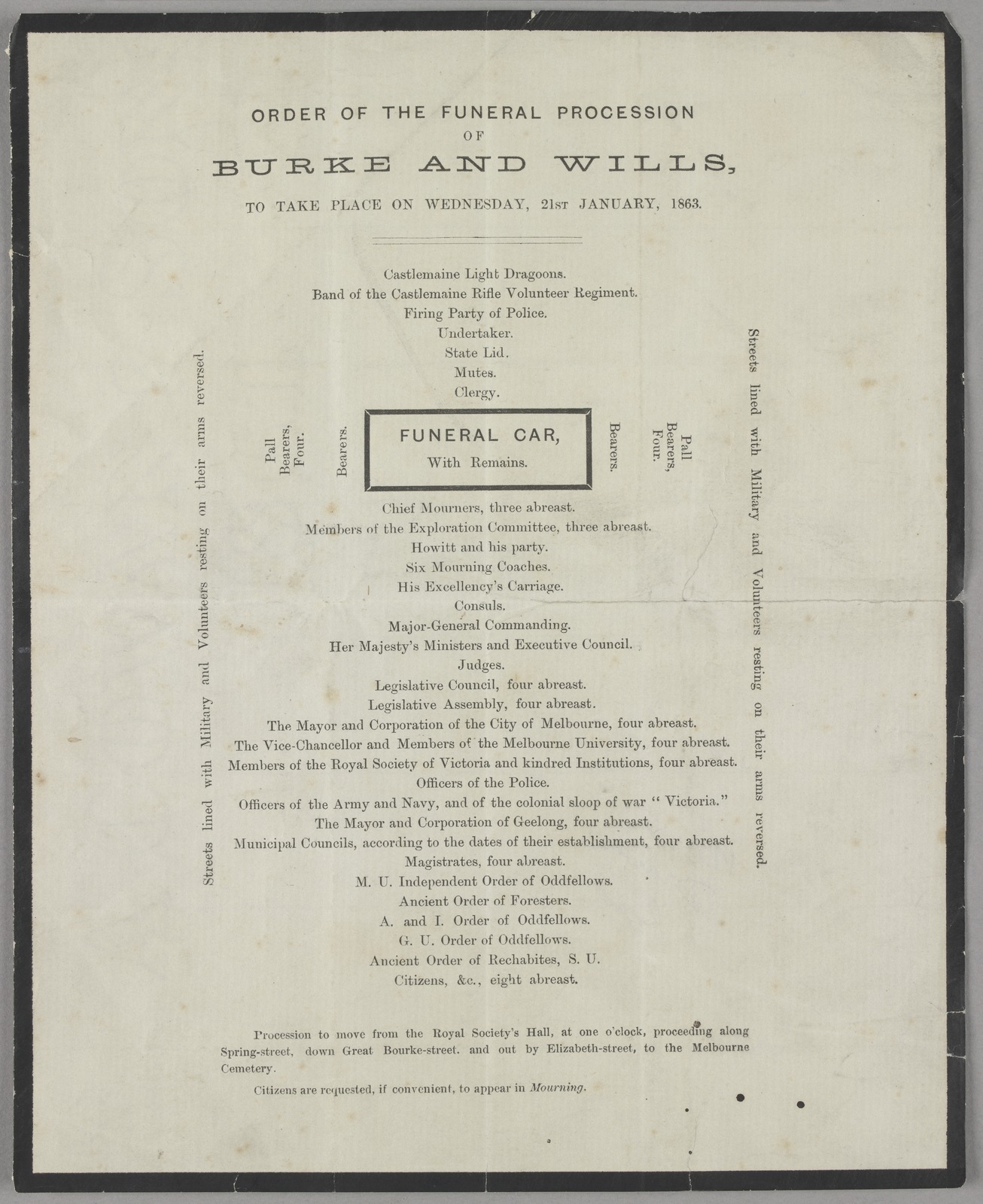

Howitt sailed from Adelaide to Melbourne on the SS ''Havilah'' with the remains of Burke and Wills in a small wooden box, arriving at Sandridge on 28 December 1862.

Howitt sailed from Adelaide to Melbourne on the SS ''Havilah'' with the remains of Burke and Wills in a small wooden box, arriving at Sandridge on 28 December 1862.  The box was taken to the hall of the Royal Society of Victoria, and a coffining ceremony was held on 31 December. This ceremony was delayed because Macadam, who held the only key to the box, arrived late. A lock smith was called but before he could pick the lock Dr Macadam, blaming his own distress for his lateness, finally arrived with the key.

The remains were placed in state for two weeks and around 100,000 people visited the Royal Society of Victoria to view the coffins.

It was originally proposed that the funeral should take place at St James Cathedral but it was decided this would be impractical because of the expected crowds and the difficulty of moving the coffins into the church from the grand mourning vehicle. It was agreed that a service at the cemetery would be appropriate.

The order and carriage of the clergy was discussed with agreement that they would walk in the procession with the Protestant clergy in front followed by the Roman Catholics. This small example of ecumenism is interesting given the general enmity and divisive

The box was taken to the hall of the Royal Society of Victoria, and a coffining ceremony was held on 31 December. This ceremony was delayed because Macadam, who held the only key to the box, arrived late. A lock smith was called but before he could pick the lock Dr Macadam, blaming his own distress for his lateness, finally arrived with the key.

The remains were placed in state for two weeks and around 100,000 people visited the Royal Society of Victoria to view the coffins.

It was originally proposed that the funeral should take place at St James Cathedral but it was decided this would be impractical because of the expected crowds and the difficulty of moving the coffins into the church from the grand mourning vehicle. It was agreed that a service at the cemetery would be appropriate.

The order and carriage of the clergy was discussed with agreement that they would walk in the procession with the Protestant clergy in front followed by the Roman Catholics. This small example of ecumenism is interesting given the general enmity and divisive

In 1862 monuments were erected in Back Creek Cemetery,

In 1862 monuments were erected in Back Creek Cemetery,

Explorer's Fountain

on Sturt and Lydiard Streets. Wills, his brother Tom and their father, Dr William Wills, had all lived in Ballarat. In 1890 a monument was erected at Royal Park, the expedition's departure point in Melbourne. The plaque on the monument states, "This memorial has been erected to mark the spot from whence the Burke and Wills Expedition started on 20 August 1860. After successfully accomplishing their mission the two brave leaders perished on their return journey at Coopers Creek in June 1861." In 1983 they were honoured on a

Burke and Wills Web – online digital archive

'' by Dave Phoenix * ''The'' elbourne''Argus'', 1861. "The Burke and Wills exploring expedition: An account of the crossing the continent of Australia from Cooper Creek to Carpentaria, with biographical sketches of Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills." Melbourne: Wilson and Mackinnon. * Bergin, Thomas John, & Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 1981. ''In the steps of Burke and Wills.'' Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Commission. . * Bergin, Thomas John, & Reader's Digest, 1996. ''Across the outback.''. Surrey Hills: Reader's Digest. . * Bonyhady, Tim, 1991. ''Burke and Wills: From Melbourne to myth.'' Balmain: David Ell Press. . * Burke and Wills Outback Conference 2003, 2005. ''The Inaugural Burke & Wills Outback Conference: Cloncurry 2003 : a collation of presentations''. Cairns: Dave Phoenix. * Clarke, Manning, 1995. ''Manning Clark's History of Australia.'' London: Pimlico, Chapter 7: "Glory, Folly and Chance", pp. 281–295. . * Clune, Frank, 1937. ''Dig: A drama of central Australia.'' Sydney: Angus and Robertson. * Colwell, Max, 1971. ''The journey of Burke and Wills.'' Sydney: Paul Hamlyn. . * Corke, David G, 1996. ''The Burke and Wills Expedition: A study in evidence.'' Melbourne: Educational Media International. . * Ferguson, Charles D, 1888. ''Experiences of a Forty-Niner during the thirty-four years residence in California and Australia.'' Cleveland, Ohio: The Williams Publishing Co. * Fitzpatrick, Kathleen, 1963. "The Burke and Wills Expedition and the Royal Society of Victoria." ''Historical Studies of Australia and New Zealand''. Vol. 10 (No. 40), pp. 470–478. * Judge, Joseph, & Scherschel, Joseph J, 1979. "First across Australia: The journey of Burke and Wills." ''National Geographic Magazine'', Vol. 155, February 1979, pp. 152–191. * Leahy, Frank, 2007. "Locating the 'Plant Camp' of the Burke and Wills expedition." ''Journal of Spatial Science'', No. 2, December 2007, pp. 1–12. * Moorehead, Alan McCrae, 1963. ''Coopers Creek.'' London: Hamish Hamilton. * Murgatroyd, Sarah, 2002. ''The Dig Tree.'' Melbourne: Text Publishing. . * Phoenix, Dave, 2003. ''From Melbourne to the Gulf: A brief history of the VEE of 1860–1.'' Cairns

Self published

. *Phoenix, Dave, 2015. Following Burke and Wills across Australia, CSIRO Publishing . *

Records of the Burke and Wills Expedition, 1857-1875.

'' Manuscript MS 13071. Australian Manuscripts Collection. State Library Victoria (Australia) *Van der Kiste, John, 2011. ''William John Wills: Pioneer of the Australian outback''. Stroud: History Press. . * Victoria: Parliament, 1862. ''Burke and Wills Commission''

Report of the Commissioners appointed to enquire into and report upon the circumstances connected with the sufferings and death of Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills, the Victorian Explorers.

Melbourne: John Ferres Government Printer. * White, John, 1992. ''Burke and Wills: The stockade and the tree.'' Footscray, Vic: The Victoria University of Technology Library in association with Footprint Press.

Burke & Wills Web – online digital archive.

A comprehensive online digital archive containing transcripts of many of the historical documents relating to the Burke & Wills Expedition.

The Burke & Wills Historical Society.

The State Library of Victoria's online exhibition and resources.

The Burke and Wills collection

at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra.

The Diary of William John Wills.

The diary written by Wills while at the Cooper from 23 April 1861 to 28 June 1861, which is held at the National Library of Australia, Canberra.

The Diary of William John Wills.

Images of the diary at the National Library of Australia.

William Strutt online collection of drawings in watercolour, ink and pencil

. held by the

The Royal Society of Victoria.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Burke And Wills Expedition 1860 in Australia 1861 in Australia History of Australia (1851–1900) Exploration of Australia History of Melbourne Botanical expeditions

The Burke and Wills expedition was organised by the

The Burke and Wills expedition was organised by the Royal Society of Victoria

The Royal Society of Victoria (RSV) is the oldest scientific society in the state of Victoria in Australia.

Foundation

In 1854 two organisations formed with similar aims and membership, these being ''The Philosophical Society of Victoria'' (fou ...

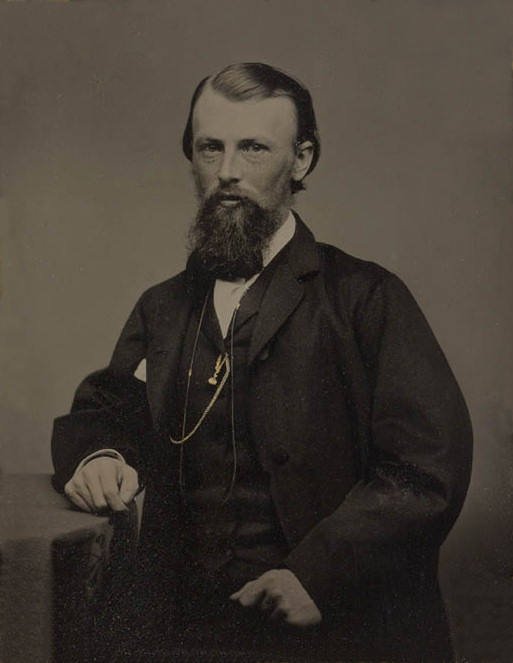

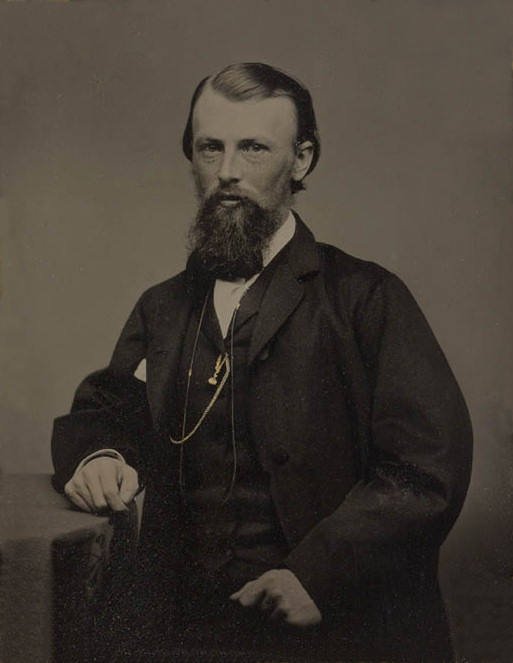

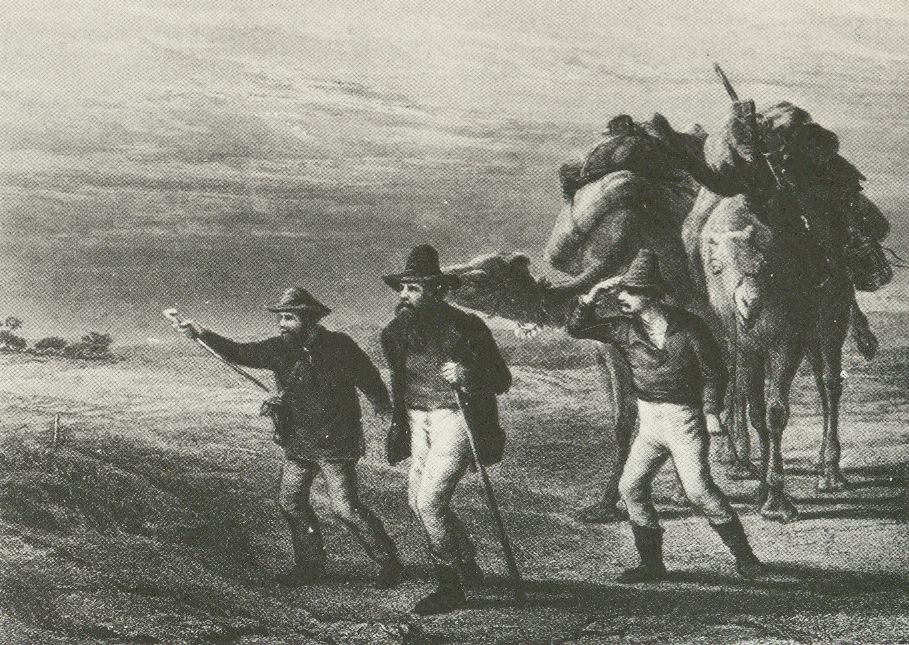

in Australia in 1860–61. It consisted of 19 men led by Robert O'Hara Burke

Robert O'Hara Burke (6 May 1821c. 28 June 1861) was an Irish soldier and police officer who achieved fame as an Australian explorer. He was the leader of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition, which was the first expedition to cross Australi ...

and William John Wills

William John Wills (5 January 1834 – ) was a British surveyor who also trained as a surgeon. Wills achieved fame as the second-in-command of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition, which was the first expedition to cross Australia from s ...

, with the objective of crossing Australia from Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

in the south, to the Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria (, ) is a large, shallow sea enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea (the body of water that lies between Australia and New Guinea). The northern boundary is ...

in the north, a distance of around 3,250 kilometres (approximately 2,000 miles). At that time most of the inland of Australia had not been explored by non-Indigenous people and was largely unknown to the European settlers.

The expedition left Melbourne in winter. Very bad weather, poor roads and broken-down horse wagons meant they made slow progress at first. After dividing the party at Menindee

Menindee (frequently but erroneously spelled "Menindie"

) is a small town in the far west of New South Wales, Australia, in Central Darling Shire, on the banks of the Darling River, with a sign-posted population of 980 and a population of 551. ...

on the Darling River

The Darling River ( Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka'') is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its conflu

ence with the Murray River at Wentworth, New South Wales. Including its longes ...

Burke made good progress, reaching Cooper Creek

The Cooper Creek (formerly Cooper's Creek) is a river in the Australian states of Queensland and South Australia. It was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its t ...

at the beginning of summer. The expedition established a depot camp at the Cooper, and Burke, Wills and two other men pushed on to the north coast (although swampland stopped them from reaching the northern coastline).

The return journey was plagued by delays and monsoon rains, and when they reached the depot at Cooper Creek, they found it had been abandoned just hours earlier. Burke and Wills died on or about 30 June 1861. Several relief expeditions were sent out, all contributing new geographical findings. Altogether, seven men died, and only one man, the Irish soldier John King, crossed the continent with the expedition and returned alive to Melbourne.

Background

Gold was discovered inVictoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

in 1851 and the subsequent gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

led to a huge influx of migrants, with the local population increasing from 29,000 in 1851 to 139,916 in 1861 (Sydney had 93,686 at the time). The colony became very wealthy and Melbourne grew rapidly to become Australia's largest city and the second largest city of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. The boom

Boom may refer to:

Objects

* Boom (containment), a temporary floating barrier used to contain an oil spill

* Boom (navigational barrier), an obstacle used to control or block marine navigation

* Boom (sailing), a sailboat part

* Boom (windsurfi ...

lasted forty years and ushered in the era known as "marvellous Melbourne

''Marvellous Melbourne: Queen City of the South'' is a 1910 documentary of Melbourne that takes the audience through the hotspots of its central business district and surrounding features. Published in 1910, the film stands as the oldest surviv ...

". The influx of educated gold seekers from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

led to rapid growth of schools, churches, learned societies, libraries and art galleries. The University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

was founded in 1855 and the State Library of Victoria

State Library Victoria (SLV) is the state library of Victoria, Australia. Located in Melbourne, it was established in 1854 as the Melbourne Public Library, making it Australia's oldest public library and one of the first free libraries in the ...

in 1856. The Philosophical Institute of Victoria was founded in 1854 and became the Royal Society of Victoria

The Royal Society of Victoria (RSV) is the oldest scientific society in the state of Victoria in Australia.

Foundation

In 1854 two organisations formed with similar aims and membership, these being ''The Philosophical Society of Victoria'' (fou ...

after receiving a Royal Charter in 1859.

By 1855 there was speculation about possible routes for the Australian Overland Telegraph Line

The Australian Overland Telegraph Line was a telegraphy system to send messages over long distances using cables and electric signals. It spanned between Darwin, in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia, and Adelaide, the capital o ...

to connect Australia to the new telegraph cable in Java and then Europe. There was fierce competition between the colonies over the route with governments recognising the economic benefits that would result from becoming the centre of the telegraph network. A number of routes were considered including Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

to Albany in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

, or Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

to the north coast of Australia and then either onto east coast, or south through the centre of the continent to Adelaide.''Exploring the Stuart Highway : further than the eye can see'', 1997, p. 24 The Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

government organised the Burke and Wills expedition to cross the continent in 1860. The South Australian government offered a reward of £2000 to encourage an expedition to find a route between South Australia and the north coast.

Exploration Committee

In 1857 the Philosophical Institute formed an ''Exploration Committee'' with the aim of investigating the practicability of fitting out an exploring expedition. While interest in inland exploration was strong in the neighbouring colonies of

In 1857 the Philosophical Institute formed an ''Exploration Committee'' with the aim of investigating the practicability of fitting out an exploring expedition. While interest in inland exploration was strong in the neighbouring colonies of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, in Victoria enthusiasm was limited. Even the anonymous donation of £1,000 (later discovered to be from Ambrose Kyte

Ambrose Henry Spencer Kyte ( – 16 November 1868) was a merchant and politician in colonial Victoria (Australia).

Kyte was born in Nenagh, County Tipperary, Tipperary, Ireland, the son of Stephen Kyte and his wife Margaret, ''née'' Mitchell.

...

) to the ''Fund Raising Committee'' of the Royal Society failed to generate much interest and it was 1860 before sufficient money was raised and the expedition was assembled.

The Exploration Committee called for offers of interest for a leader for the ''Victorian Exploring Expedition''. Only two members of the committee, Ferdinand von Mueller

Baron Sir Ferdinand Jacob Heinrich von Mueller, (german: Müller; 30 June 1825 – 10 October 1896) was a German-Australian physician, geographer, and most notably, a botanist. He was appointed government botanist for the then colony of Vict ...

and Wilhelm Blandowski, had any experience in exploration but due to factionalism both were consistently outvoted. Several people were considered for the post of leader and the Society held a range of meetings in early 1860. Robert O'Hara Burke

Robert O'Hara Burke (6 May 1821c. 28 June 1861) was an Irish soldier and police officer who achieved fame as an Australian explorer. He was the leader of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition, which was the first expedition to cross Australi ...

was selected by committee ballot as the leader, and William John Wills

William John Wills (5 January 1834 – ) was a British surveyor who also trained as a surgeon. Wills achieved fame as the second-in-command of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition, which was the first expedition to cross Australia from s ...

was recommended as surveyor, navigator and third-in-command. Burke had no experience in exploration and it is strange that he was chosen to lead the expedition. Burke was an Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

-born ex-officer with the Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n army, and later became police superintendent with virtually no skills in bushcraft. Wills was more adept than Burke at living in the wilderness, but it was Burke's leadership that was especially detrimental to the mission.

Rather than take cattle to be slaughtered during the trip the Committee decided to experiment with dried meat. The weight required three extra wagons and was to slow the expedition down appreciably.

Instructions from the Exploration Committee

The Victorian Exploration Committee gave Burke written instructions. These included suggestions for the route to take but also gave Burke discretion depending on conditions and barriers he might encounter. The instructions were signed by the Honorary Secretary Dr John Macadam and in part advised:

The Victorian Exploration Committee gave Burke written instructions. These included suggestions for the route to take but also gave Burke discretion depending on conditions and barriers he might encounter. The instructions were signed by the Honorary Secretary Dr John Macadam and in part advised:

Members of the Exploration Committee

The Exploration Committee of the Royal Society of Victoria included: * Sir William Foster Stawell, Chief Justice of Victoria * Dr David Elliott Wilkie MD., Treasurer * Dr John Macadam, Honorary Secretary * Professor Georg Neumayer * DrFerdinand von Mueller

Baron Sir Ferdinand Jacob Heinrich von Mueller, (german: Müller; 30 June 1825 – 10 October 1896) was a German-Australian physician, geographer, and most notably, a botanist. He was appointed government botanist for the then colony of Vict ...

, Government Botanist

* Sir Frederick McCoy

Sir Frederick McCoy (1817 – 13 May 1899), was an Irish palaeontologist, zoologist, and museum administrator, active in Australia. He is noted for founding the Botanic Garden of the University of Melbourne in 1856.

Early life

McCoy was the so ...

, Melbourne University's first professor

* The Hon. Captain Andrew Clarke Andrew Clarke may refer to:

*Andrew Clarke (British Army officer, born 1793) (1793–1847), Governor of Western Australia

*Sir Andrew Clarke (British Army officer, born 1824) (1824–1902), Governor of the Straits Settlements, son of the above

*And ...

* Dr Richard Eades, Mayor of Melbourne

This is a list of the mayors and lord mayors of the City of Melbourne, a Local government in Australia, local government area of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia.

Mayors (1842–1902)

Lord mayors (1902–1980)

The title of "Lord ...

* Charles Whybrow Ligar, Government Surveyor General

* The Hon Sir Francis Murphy, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly

* Lieutenant John Randall Pascoe, JP

* Captain Francis Cadell

* Alfred Selwyn Esq., Government Geologist

* Reverend Father Dr John Ignatius Bleasdale

* Clement Hodgkinson

Clement Hodgkinson (1818 – 5 September 1893) was a notable English naturalist, explorer and surveyor of Australia. He was Victorian Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands and Survey from 1861 to 1874.

Exploration in New South Wales

Qualified ...

Esq.

* Dr J William McKenna

* Edward Wilson Edward Wilson may refer to:

*Ed Wilson (artist) (1925–1996), African American sculptor

* Ed Wilson (baseball) (1875–?), American baseball player

* Ed Wilson (singer) (1945–2010), Brazilian singer-songwriter

*Ed Wilson, American television exe ...

, Editor of the ''Argus

Argus is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek word ''Argos''. It may refer to:

Greek mythology

* See Argus (Greek myth) for mythological characters named Argus

**Argus (king of Argos), son of Zeus (or Phoroneus) and Niobe

**Argus (son of Ar ...

''

* Dr William Gilbee

* Sizar Elliott Esq.

* Dr Solomon Iffla

* Angus McMillan Esq.

* James Smith Esq.

* John Watson Esq.

Camels

Camels

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

had been used successfully in desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

exploration in other parts of the world, but by 1859 only seven camels had been imported into Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

.

The Victorian Government

The Victoria State Government, also referred to as just the Victorian Government, is the state-level authority for Victoria, Australia. Like all state governments, it is formed by three independent branches: the executive, the judicial, and th ...

appointed George James Landells

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

to purchase 24 camels in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

for use in desert exploration. The animals arrived in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

in June 1860 and the Exploration Committee purchased an additional six from George Coppin's Cremorne Gardens. The camels were initially housed in the stables at Parliament House

Parliament House may refer to:

Australia

* Parliament House, Canberra, Parliament of Australia

* Parliament House, Adelaide, Parliament of South Australia

* Parliament House, Brisbane, Parliament of Queensland

* Parliament House, Darwin, Parliame ...

and later moved to Royal Park. Twenty-six camels were taken on the expedition, with six (two females with their two young calves and two males) being left in Royal Park.

Departure from Melbourne

The expedition set off from

The expedition set off from Royal Park, Melbourne

Royal Park is the largest of Melbourne's inner city parks (). It is located north of the Melbourne CBD, in Victoria, Australia, in the suburb of Parkville.

Many sporting facilities are provided including the North Park Tennis Club, Royal P ...

at about 4 pm on 20 August 1860 watched by around 15,000 spectators. The 19 men of the expedition included six Irishmen

The Irish ( ga, Muintir na hÉireann or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common history and culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has been co ...

, five Englishmen

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in O ...

, three Afghan

Afghan may refer to:

*Something of or related to Afghanistan, a country in Southern-Central Asia

*Afghans, people or citizens of Afghanistan, typically of any ethnicity

** Afghan (ethnonym), the historic term applied strictly to people of the Pas ...

and one India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

n camel driver

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

s, three Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

and an American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

. They took 23 horses, 6 wagons and 26 camels.

The expedition took a large amount of equipment, including enough food to last two years, a cedar-topped oak camp table with two chairs, rockets, flags and a Chinese gong; the equipment all together weighed as much as 20 tonnes.

Committee member Captain Francis Cadell had offered to transport the supplies from Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

up the Murray

Murray may refer to:

Businesses

* Murray (bicycle company), an American manufacturer of low-cost bicycles

* Murrays, an Australian bus company

* Murray International Trust, a Scottish investment trust

* D. & W. Murray Limited, an Australian who ...

to the junction with the Darling River to be collected on the way.

However, Burke declined his offer, possibly because Cadell had opposed Burke's appointment as leader of the expedition.

Everything was instead loaded onto six wagons. One wagon broke down before it had even left Royal Park and by midnight of the first day the expedition had reached only Essendon Essendon may refer to:

Australia

*Electoral district of Essendon

*Electoral district of Essendon and Flemington

*Essendon, Victoria

**Essendon railway station

**Essendon Airport

*Essendon Football Club in the Australian Football League

United King ...

on the edge of Melbourne. At Essendon two more wagons broke down. Heavy rains and bad roads made travelling through Victoria difficult and time-consuming. The party arrived at Lancefield

Lancefield is a town in the Shire of Macedon Ranges local government area in Victoria, Australia north of the state capital, Melbourne and had a population of 2,743 at the 2021 census.

History

The area was used by the indigenous aborigin ...

on 23 August and set up their fourth camp. The first day off was taken on Sunday, 26 August at Camp VI in Mia Mia.

The expedition reached

The expedition reached Swan Hill

Swan Hill is a city in the northwest of Victoria, Australia on the Murray Valley Highway and on the south bank of the Murray River, downstream from the junction of the Loddon River. At , Swan Hill had a population of 11,508.

Indigenous Peopl ...

on 6 September and arrived in Balranald

Balranald is a town within the local government area of Balranald Shire, in the Riverina district of New South Wales, Australia.

The town of Balranald is located where the Sturt Highway crosses the Murrumbidgee River in a remote, semi-desert ...

on 15 September. There, to lighten the load, they left behind their sugar, lime juice and some of their guns and ammunition. At Gambala on 24 September, Burke decided to load some of the provisions onto the camels for the first time, and to lessen the burden on the horses he ordered the men to walk. He also ordered that personal luggage be restricted to . At Bilbarka on the Darling, Burke and his second-in-command, Landells, argued after Burke decided to dump the 60 gallons (≈270 litres) of rum that Landells had brought to feed to the camels in the belief that it prevented scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

. At Kinchega on the Darling, Landells resigned from the expedition, followed by the expedition's surgeon

In modern medicine, a surgeon is a medical professional who performs surgery. Although there are different traditions in different times and places, a modern surgeon usually is also a licensed physician or received the same medical training as ...

, Dr Hermann Beckler

Dr. Hermann Beckler (28 September 1828, in Höchstädt an der Donau – 10 December 1914, in Fischen im Allgäu) was a German doctor with an interest in botany. He went to Australia to collect specimen for Ferdinand von Mueller and served as medi ...

. Third-in-command Wills was promoted to second-in-command. They reached Menindee

Menindee (frequently but erroneously spelled "Menindie"

) is a small town in the far west of New South Wales, Australia, in Central Darling Shire, on the banks of the Darling River, with a sign-posted population of 980 and a population of 551. ...

on 12 October having taken two months to travel from Melbourne—the regular mail coach did the journey in little more than a week. Two of the expedition's five officers had resigned, thirteen members of the expedition had been fired and eight new men had been hired.

In July 1859 the South Australian government

The Government of South Australia, also referred to as the South Australian Government, SA Government or more formally, His Majesty’s Government, is the Australian state democratic administrative authority of South Australia. It is modelled o ...

offered a reward of £2,000 (about A$289,000 in 2011 dollars) for the first successful south–north crossing of the continent west of the 143rd line of longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

. The experienced explorer John McDouall Stuart

John McDouall Stuart (7 September 18155 June 1866), often referred to as simply "McDouall Stuart", was a Scottish explorer and one of the most accomplished of all Australia's inland explorers.

Stuart led the first successful expedition to tra ...

had taken up the challenge. Burke was concerned Stuart might beat him to the north coast and he soon grew impatient with their slow progress often averaging only an hour. Burke split the group, taking the strongest horses, seven of the fittest men and a small amount of equipment, with plans to push on quickly to Cooper Creek

The Cooper Creek (formerly Cooper's Creek) is a river in the Australian states of Queensland and South Australia. It was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its t ...

(then known as Cooper's Creek) and then wait for the others to catch up. They left Menindee on 19 October, guided by William Wright who was appointed third-in-command. Travel was relatively easy because recent rain made water abundant, while in unusually mild weather temperatures exceeded only twice before the party reached Cooper Creek

The Cooper Creek (formerly Cooper's Creek) is a river in the Australian states of Queensland and South Australia. It was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its t ...

. At Torowotto Swamp Wright was sent back to Menindee alone to bring up the remainder of the men and supplies and Burke continued on to Cooper Creek.

Cooper Creek

Augustus Charles Gregory

Sir Augustus Charles Gregory (1 August 1819 – 25 June 1905) was an English-born Australian explorer and surveyor. Between 1846 and 1858 he undertook four major expeditions. He was the first Surveyor-General of Queensland. He was appointed a ...

in 1858. Burke arrived at the Cooper on 11 November and they formed a depot at Camp LXIII (Camp 63) while they conducted reconnaissance to the north. A plague of rats forced the men to move camp and they formed a second depot further downstream at Bullah Bullah Waterhole. This was Camp LXV (Camp 65) and they erected a stockade

A stockade is an enclosure of palisades and tall walls, made of logs placed side by side vertically, with the tops sharpened as a defensive wall.

Etymology

''Stockade'' is derived from the French word ''estocade''. The French word was derived ...

and named the place Fort Wills.

It was thought that Burke would wait at Cooper Creek until autumn (March the next year) so that they would avoid having to travel during the hot Australian summer. However, Burke waited only until Sunday, 16 December before deciding to make a dash for the Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria (, ) is a large, shallow sea enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea (the body of water that lies between Australia and New Guinea). The northern boundary is ...

. He split the group again, leaving William Brahe

William is a male given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norm ...

in charge of the depot, with Dost Mahomet, William Patton and Thomas McDonough. Burke, Wills, John King and Charles Gray set off for the Gulf with six camels, one horse and enough food for just three months. By now it was mid-summer and the daily temperature often reached in the shade, and in the Strzelecki and Sturt Stony Desert

Sturt Stony Desert (previously Sturt's Stony Desert) is an area in the north-east of South Australia, far south western border area of Queensland and the far west of New South Wales.

It was named by Charles Sturt in 1844, while he was trying ...

s there was very little shade to be found. Brahe was ordered by Burke to wait for three months; however, the more conservative Wills had reviewed the maps and developed a more realistic view of the task ahead, and secretly instructed Brahe to wait for four months.

Gulf of Carpentaria

Except for the heat, travel was easy. As a result of recent rains water was still easy to find and the Aborigines, contrary to expectations, were peaceful. On 9 February 1861 they reached the Little Bynoe River, an arm of theFlinders River

The Flinders River is the longest river in Queensland, Australia, at approximately . It was named in honour of the explorer Matthew Flinders. The catchment is sparsely populated and mostly undeveloped. The Flinders rises on the western slopes ...

delta, where they found they could not reach the ocean because of the mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evoluti ...

swamps in their way. Burke and Wills left the camels behind with King and Gray at Camp CXIX (Camp 119), and set off through the swamps, although after they decided to turn back. By this stage, they were desperately short of supplies. They had food left for 27 days, but it had already taken them 59 days to travel from Cooper Creek.

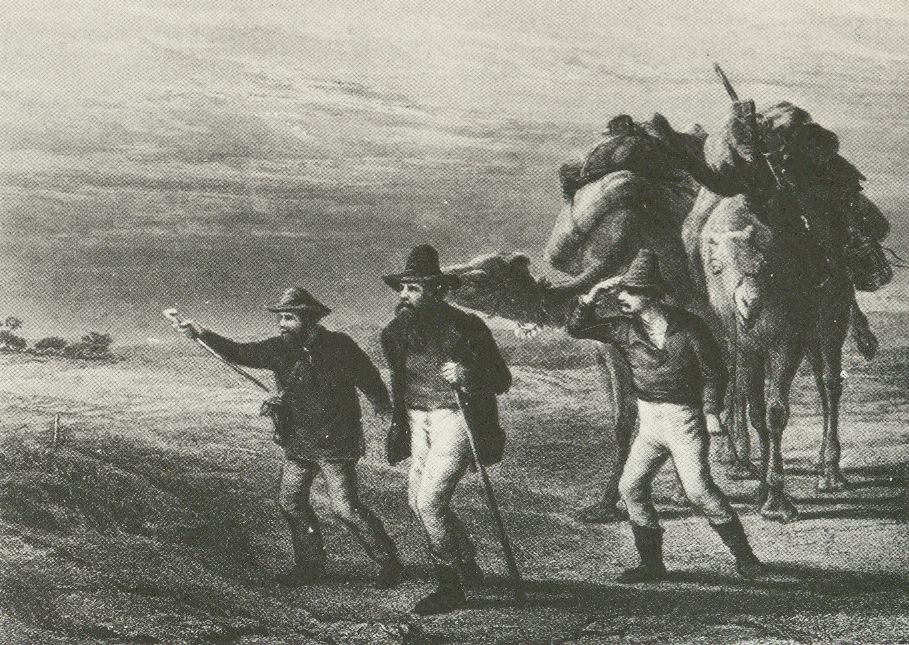

On their way north, the weather had been hot and dry, but on the way back the

On their way north, the weather had been hot and dry, but on the way back the wet season

The wet season (sometimes called the Rainy season) is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs. It is the time of year where the majority of a country's or region's annual precipitation occurs. Generally, the sea ...

broke and the tropical monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

al rains began. A camel named ''Golah Sing'' was abandoned on 4 March when it was unable to continue. Three other camels were shot and eaten along the way and they shot their only horse, ''Billy'', on 10 April on the Diamantina River

The Diamantina River is a major river located in Central West Queensland and the far north of South Australia.

The river was named by William Landsborough in 1866 for Lady Diamantina Bowen (née Roma), wife of Sir George Bowen, the first Govern ...

, south of what is today the town of Birdsville

Birdsville is a rural town and locality in the Shire of Diamantina, Queensland, Australia. In the the locality of Birdsville had a population of 110 people. It is a popular tourist destination with many people using it as a starting point acro ...

. Equipment was abandoned at a number of locations as the number of pack animal

A pack animal, also known as a sumpter animal or beast of burden, is an individual or type of working animal used by humans as means of transporting materials by attaching them so their weight bears on the animal's back, in contrast to draft anim ...

s was reduced. One of these locations, ''Return Camp 32'', was relocated in 1994 and The Burke and Wills Historical Society mounted an expedition to verify the discovery of camel bones in 2005.

To extend their food supply, they ate portulaca

''Portulaca'' (, is the type genus of the flowering plant family Portulacaceae, with over 100 species, found in the tropics and warm temperate regions. They are known as the purslanes.

Common purslane (''Portulaca oleracea'') is widely consume ...

. Gray also caught an Python

Python may refer to:

Snakes

* Pythonidae, a family of nonvenomous snakes found in Africa, Asia, and Australia

** ''Python'' (genus), a genus of Pythonidae found in Africa and Asia

* Python (mythology), a mythical serpent

Computing

* Python (pro ...

(probably ''Aspidites melanocephalus

The black-headed python (''Aspidites melanocephalus'') Mehrtens JM (1987). ''Living Snakes of the World in Color''. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. . is a species of snake in the Pythonidae (the python family). The species is endemic to Au ...

'', a black-headed python), which they ate. Both Burke and Gray immediately came down with dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

. Gray was ill, but Burke thought he was "gammoning" (pretending). On 25 March on the Burke River (just south of what is now the town of Boulia

Boulia () is an outback town and locality in the Shire of Boulia, Queensland, Australia. In the , Boulia had a population of 301 people.

Boulia is the administrative centre of the Boulia Shire, population approximately 600, which covers an area ...

), Gray was caught stealing skilligolee (a type of watery porridge) and Burke beat him. By 8 April, Gray could not walk; he died on 17 April of dysentery at a place they called Polygonum Swamp. The location of Gray's death is unknown, although it is generally believed to be Lake Massacre in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. While the possibility that Burke killed Gray has been discounted, the severity of the beating Burke gave has been widely debated. The three surviving men stopped for a day to bury Gray, and to recover their strength—they were by this stage very weak from hunger and exhaustion. They finally reached Cooper Creek on 21 April, only to find that the camp had been abandoned several hours earlier.

Return to Cooper Creek

Burke had asked Brahe and the depot party to remain at the camp on the Cooper for 13 weeks. The party had actually waited for 18 weeks and was running low on supplies and starting to feel the effects of scurvy; they had come to believe that Burke would never return from the Gulf. After one of his men had injured his leg, Brahe decided to return to Menindee, but before leaving buried some provisions in case Burke did return, and blazed (cut or carved) a message on a tree to mark the spot.

Brahe left the depot on Cooper Creek on the morning of Sunday, 21 April 1861. Burke, Wills and King returned that evening. Finding the camp deserted, they dug up the cache of supplies, and a letter explaining that the party had given up waiting and had left. Burke's team had missed them by only nine hours. The three men and two remaining camels were exhausted; they had no hope of catching up to the main party.

Burke had asked Brahe and the depot party to remain at the camp on the Cooper for 13 weeks. The party had actually waited for 18 weeks and was running low on supplies and starting to feel the effects of scurvy; they had come to believe that Burke would never return from the Gulf. After one of his men had injured his leg, Brahe decided to return to Menindee, but before leaving buried some provisions in case Burke did return, and blazed (cut or carved) a message on a tree to mark the spot.

Brahe left the depot on Cooper Creek on the morning of Sunday, 21 April 1861. Burke, Wills and King returned that evening. Finding the camp deserted, they dug up the cache of supplies, and a letter explaining that the party had given up waiting and had left. Burke's team had missed them by only nine hours. The three men and two remaining camels were exhausted; they had no hope of catching up to the main party.

They decided to rest and recuperate, living off the supplies left in the cache. Wills and King wanted to follow their outward track back to Menindee, but Burke overruled them and decided to attempt to reach the furthest outpost of pastoral settlement in

They decided to rest and recuperate, living off the supplies left in the cache. Wills and King wanted to follow their outward track back to Menindee, but Burke overruled them and decided to attempt to reach the furthest outpost of pastoral settlement in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, a cattle station

In Australia and New Zealand, a cattle station is a large farm ( station is equivalent to the American ranch), the main activity of which is the rearing of cattle. The owner of a cattle station is called a '' grazier''. The largest cattle stati ...

near Mount Hopeless. This would mean travelling southwest through the desert for . They wrote a letter explaining their intentions and reburied it in the cache under the marked tree in case a rescue party visited the area. Unfortunately, they did not change the mark on the tree or alter the date. On 23 April they set off, following the Cooper downstream and then heading out into the Strzelecki Desert

The Strzelecki Desert is located in the Far North Region of South Australia, South West Queensland and western New South Wales. It is positioned in the northeast of the Lake Eyre Basin, and north of the Flinders Ranges. Two other deserts occup ...

towards Mount Hopeless.

Meanwhile, while returning to Menindee, Brahe had met with Wright trying to reach the Cooper with the supplies. The two men decided to go back to Cooper Creek to see if Burke had returned. When they arrived on Sunday, 8 May, Burke had already left for Mount Hopeless, and the camp was again deserted. Burke and Wills were away by this point. As the mark and date on the tree were unaltered, Brahe and Wright assumed that Burke had not returned, and did not think to check whether the supplies were still buried. They left to rejoin the main party and return to Menindee.

Controversy

Brahe might have stayed at Cooper Creek longer, but one of his men, theblacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

Patton, had injured his leg after being thrown from his horse, so they decided to leave for Menindee that morning. Patton was to die from complications six weeks later. Burke and Wills discussed catching up with them, but they were too exhausted and decided to wait.

Meanwhile, the other mission led by William Wright was having terrible problems of its own. Wright was supposed to bring supplies up from Menindee to Cooper Creek, but it was the end of January 1861 before he managed to set out from Menindee. Wright's delay subsequently resulted in his being blamed for the deaths of Burke and Wills. In 1963, Alan Moorehead

Alan McCrae Moorehead, (22 July 1910 – 29 September 1983) was a war correspondent and author of popular histories, most notably two books on the nineteenth-century exploration of the Nile, ''The White Nile'' (1960) and ''The Blue Nile'' (196 ...

wrote of the 'mystery' surrounding Wright's delay:

An in-depth study of Wright's action formed a part of Dr Tom Bergin's 1982 MA thesis. Bergin, who recreated the original journey from Cooper Creek to the Gulf of Carpentaria with camels in 1978, showed that a lack of money and too few pack animals to carry the supplies meant Wright was placed in an unenviable position. His requests to the Exploration Committee were not acted on until early January, by which time the hot weather and lack of water meant that the party moved extremely slowly. They were harassed by the Bandjigali and Karenggapa Murris, and three of the men, Dr Ludwig Becker, Charles Stone and William Purcell, died from malnutrition on the trip. On his way north, Wright camped at Koorliatto Waterhole on the Bulloo River

The Bulloo River is an isolated drainage system in western Queensland, central Australia. Its floodplain, which extends into northern New South Wales, is an important area for waterbirds when inundated. It comprises most of the Bulloo-Banc ...

while he tried to find Burke's tracks to Cooper Creek. While he was there he met Brahe, who was on his way back from the Cooper to Menindee.

The ''Dig Tree''

Cooper Creek

The Cooper Creek (formerly Cooper's Creek) is a river in the Australian states of Queensland and South Australia. It was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its t ...

, both are coolibahs (''Eucalyptus coolabah

''Eucalyptus coolabah'', commonly known as coolibah or coolabah, is a species of tree found in eastern inland Australia. It has rough bark on part or all of the trunk, smooth powdery cream to pink bark above, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, ...

'' formerly ''Eucalyptus microtheca'') and both are estimated to be at least 250 years old. One tree has two blazes on it; one denoting the date of arrival and the date of departure "DEC-6-60" carved over "APR-21-61" and the other showing the initial "B" (for Burke) carved over the Roman numerals for (camp) 65; "B" over "LXV". The date blaze has grown closed and only the camp number blaze remains visible today. On an adjacent smaller tree Brahe carved the instruction to 'DIG'. The exact inscription is not known, but is variously recalled to be "DIG", "DIG under", "DIG 3 FT N.W.", "DIG 3FT N.E." or "DIG 21 APR 61".

Initially the tree with the Date and Camp Number blaze was known as "Brahe's Tree" or the "Depot Tree" and the tree under which Burke died attracted most attention and interest. However, the tree at Depot Camp LXV became known as the "Dig Tree" from at least 1912.

In 1899 John Dick carved a likeness of Burke's face in a nearby tree along with his initials, his wife's initials and the date.

Burke, Wills and King alone at Cooper Creek

After leaving the ''Dig Tree'' they rarely travelled more than a day. One of the two remaining camels, ''Landa'', became bogged in Minkie Waterhole and the other, ''Rajah'' was shot when he could travel no further. Without pack animals, Burke, Wills and King were unable to carry enough water to leaveCooper Creek

The Cooper Creek (formerly Cooper's Creek) is a river in the Australian states of Queensland and South Australia. It was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its t ...

and cross the Strzelecki Desert

The Strzelecki Desert is located in the Far North Region of South Australia, South West Queensland and western New South Wales. It is positioned in the northeast of the Lake Eyre Basin, and north of the Flinders Ranges. Two other deserts occup ...

to Mount Hopeless, and so the three men were unable to leave the creek. Their supplies were running low and they were malnourished and exhausted. The Cooper Creek Aborigines, the Yandruwandha people

The Yandruwandha, alternatively known as ''Jandruwanta,'' are an Aboriginal Australian people living in the Lakes area of South Australia, south of Cooper Creek and west of the Wangkumara people.

Language

Yandruwandha is a generic term referrin ...

, gave them fish, beans called ''padlu'' and a type of damper

A damper is a device that deadens, restrains, or depresses. It may refer to:

Music

* Damper pedal, a device that mutes musical tones, particularly in stringed instruments

* A mute for various brass instruments

Structure

* Damper (flow), a mechan ...

made from the ground sporocarps of the ''ngardu'' (nardoo) plant (''Marsilea drummondii

''Marsilea drummondii'' is a species of fern known by the common name nardoo. It is native to Australia, where it is widespread and common, particularly in inland regions. It is a rhizomatous perennial aquatic fern that roots in mud substrates an ...

'') in exchange for sugar.

At the end of May 1861, Wills returned to the ''Dig Tree'' to put his diary, notebook and journals in the cache for safekeeping. Burke bitterly criticised Brahe in his journal for not leaving behind any supplies or animals. While Wills was away from camp, Burke foolishly shot his pistol at one of the Aborigines, causing the whole group to flee. Within a month of the Aborigines' departure, Burke and Wills both perished.

Death

Towards the end of June 1861 as the three men were following the Cooper upstream to find the Yandruwandha campsite, Wills became too weak to continue. He was left behind at his own insistence at Breerily Waterhole with some food, water and shelter. Burke and King continued upstream for another two days until Burke became too weak to continue. The next morning Burke died. King stayed with his body for two days and then returned downstream to Breerily Waterhole, where he found that Wills had died as well.

The exact dates on which Burke and Wills died are unknown and different dates are given on various memorials in Victoria. The Exploration Committee fixed 28 June 1861 as the date both explorers died. King found a group of Yandruwandha willing to give him food and shelter and in return he shot birds to contribute to their supplies.

Towards the end of June 1861 as the three men were following the Cooper upstream to find the Yandruwandha campsite, Wills became too weak to continue. He was left behind at his own insistence at Breerily Waterhole with some food, water and shelter. Burke and King continued upstream for another two days until Burke became too weak to continue. The next morning Burke died. King stayed with his body for two days and then returned downstream to Breerily Waterhole, where he found that Wills had died as well.

The exact dates on which Burke and Wills died are unknown and different dates are given on various memorials in Victoria. The Exploration Committee fixed 28 June 1861 as the date both explorers died. King found a group of Yandruwandha willing to give him food and shelter and in return he shot birds to contribute to their supplies.

Rescue expeditions

In 1861, five expeditions were sent out to search for Burke and Wills; two commissioned by the Exploration Committee of theRoyal Society of Victoria

The Royal Society of Victoria (RSV) is the oldest scientific society in the state of Victoria in Australia.

Foundation

In 1854 two organisations formed with similar aims and membership, these being ''The Philosophical Society of Victoria'' (fou ...

, one by the Government of Victoria

The Victoria State Government, also referred to as just the Victorian Government, is the state-level authority for Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia. Like all state governments, it is formed by three independent branches: the executive ...

one by the Government of Queensland

The Queensland Government is the democratic administrative authority of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland. The Government of Queensland, a parliamentary system, parliamentary constitutional monarchy was form ...

and one by the Government of South Australia

The Government of South Australia, also referred to as the South Australian Government, SA Government or more formally, His Majesty’s Government, is the Australian state democratic administrative authority of South Australia. It is modelled o ...

. HMCSS ''Victoria'' was sent from Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

to search the Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria (, ) is a large, shallow sea enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea (the body of water that lies between Australia and New Guinea). The northern boundary is ...

for the missing expedition, and SS ''Firefly'' sailed from Melbourne to Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

where they picked up Landsborough's Queensland Relief Expedition. The other expeditions went overland, with Howitt's Victorian Contingent Party departing from Melbourne, McKinlay's South Australian Burke Relief Expedition departing from Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

and Walker's Victorian Relief Expedition departing from Rockhampton

Rockhampton is a city in the Rockhampton Region of Central Queensland, Australia. The population of Rockhampton in June 2021 was 79,967, Estimated resident population, 30 June 2018. making it the fourth-largest city in the state outside of the ...

.

Victorian Contingent Party

After six months without receiving word from the Burke expedition, the media began questioning its whereabouts. Public pressure for answers increased and on 13 June 1861, the Exploration Committee agreed to send a search party to find the Burke and Wills expedition and, if necessary, offer them support. The Victorian Contingent Party left Melbourne on 26 June 1861 under the leadership ofAlfred William Howitt

Alfred William Howitt , (17 April 1830 – 7 March 1908), also known by author abbreviation A.W. Howitt, was an Australian anthropologist, explorer and naturalist. He was known for leading the Victorian Relief Expedition, which set out to es ...

. At the Loddon River

The Loddon River, an inland river of the northcentral catchment, part of the Murray-Darling basin, is located in the lower Riverina bioregion and Central Highlands and Loddon Mallee regions of the Australian state of Victoria. The headwaters ...

, Howitt met Brahe, who was returning from Cooper Creek. As Brahe did not have knowledge of Burke's whereabouts, Howitt decided a much larger expedition would be required to find the missing party. Leaving three of his men at the river, Howitt returned to Melbourne with Brahe to update the Exploration Committee. On 30 June, the expanded expedition left to follow Burke's trail. On 3 September, the party reached Cooper Creek, on 11 September the ''Dig Tree'', and four days later Edwin Welch

Edwin James Welch (26 December 1838 – 24 September 1916) was an English naval cadet, surveyor, photographer, newspaper proprietor, writer and journalist. Welch discovered John King, sole survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition.

Early life

...

found King living with the Yandruwandha. Over the next nine days, Howitt found the remains of Burke and Wills and buried them. In pitiful condition, King survived the two-month trip back to Melbourne, and died eleven years later, aged 33, never having recovered his health. He is buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery

The Melbourne General Cemetery is a large (43 hectare) necropolis located north of the city of Melbourne in the suburb of Carlton North.

The cemetery is notably the resting place of four Prime Ministers of Australia, more than any other nec ...

.

HMVS ''Victoria''

On 4 August 1861, HMVS ''Victoria'' under the Command of

On 4 August 1861, HMVS ''Victoria'' under the Command of William Henry Norman

William Henry Norman (1812–1869) was a sea captain in Australia. As commander of HMVS ''Victoria'', he engaged in the First Taranaki War in New Zealand and the search for explorers Burke and Wills.

Early life

William Henry Norman was born in ...

sailed from Hobson's Bay

The City of Hobsons Bay is a local government area in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It comprises the south-western suburbs between 6 and 20 km from the Melbourne city centre.

It was founded on 22 June 1994 during the amalgamation of l ...

in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

with orders to search the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Victorian Government

The Victoria State Government, also referred to as just the Victorian Government, is the state-level authority for Victoria, Australia. Like all state governments, it is formed by three independent branches: the executive, the judicial, and th ...

also chartered ''Firefly'' (188 tons, built 1843) to assist with transportation. ''Firefly'' left Hobson's Bay (Melbourne) on 29 July and arrived at Moreton Bay

Moreton Bay is a bay located on the eastern coast of Australia from central Brisbane, Queensland. It is one of Queensland's most important coastal resources. The waters of Moreton Bay are a popular destination for recreational anglers and are ...

(Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

) on 10 August 1861, the same day as HMVS ''Victoria''. ''Firefly'' transported the Queensland party led by William Landsborough

William Landsborough (21 February 1825 – 16 March 1886) was an explorer of Australia and notably he was the first explorer to complete a North-to-South crossing of Australia. He was a member of the Queensland Legislative Council.

Early ...

, and thirty horses. The two ships sailed for the Gulf of Carpentaria on 24 August 1861.

The ships became separated in a storm on 1 September and ''Firefly'' hit a reef off Sir Charles Hardy Islands

Sir Charles Hardy Islands is in the reef of the same name adjacent to Pollard Channel & Blackwood Channel about 40 km east of Cape Grenville off Cape York Peninsula.

Shipwrecks

Shipwrecks in this area include:

''Charles Eaton''

* ...

. The crew were able to free and save 26 of the horses by cutting a hole in the side of the ship. ''Victoria'' arrived shortly afterwards. ''Firefly'' was repaired and able to be towed by ''Victoria''. They recommenced their journey on 22 September, arriving near Sweers Island

Sweers Island is an island in the South Wellesley Islands in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland, Australia. Privately owned via a perpetual lease and with the only residents being the owners and workers at the resort, the island is within the ...

and Albert River on 29 September, where they rendezvoused with the brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

''Gratia'' and the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

''Native Lass'', which had also been chartered by the Victorian Government as support. They established a land base on Sweers, after visiting Bentinck Island

Bentinck Island is a small island in the Strait of Juan de Fuca just off the southern tip of Vancouver Island in Metchosin, British Columbia, Canada near Race Rocks. It served as a leper colony beginning in 1924, when the federal government shut d ...

and finding it inhabited by "hostile natives".

Using ''Victoria'' boats, ''Firefly'' was manoeuvred up the Albert River some to a suitable place to transfer the horses and stores to land.

Queensland Relief Expedition

After disembarking from ''Victoria'' in November, the Queensland Relief Expedition, under the leadership ofWilliam Landsborough

William Landsborough (21 February 1825 – 16 March 1886) was an explorer of Australia and notably he was the first explorer to complete a North-to-South crossing of Australia. He was a member of the Queensland Legislative Council.

Early ...

, searched the gulf coast for the missing expedition. The party proceeded south and while they found no trace of the Burke and Wills party they continued all the way to Melbourne arriving in August 1862. This was the first European expedition to traverse mainland Australia from northern to southern coast. In 1881, the Queensland Parliament awarded Landsborough £2000 for his achievements as an explorer.

Victorian Relief Expedition

Frederick Walker led the Victorian Relief Expedition. The party, consisting of twelve mounted men, seven of them ex-troopers from the Native Police Corps, started from

Frederick Walker led the Victorian Relief Expedition. The party, consisting of twelve mounted men, seven of them ex-troopers from the Native Police Corps, started from Rockhampton

Rockhampton is a city in the Rockhampton Region of Central Queensland, Australia. The population of Rockhampton in June 2021 was 79,967, Estimated resident population, 30 June 2018. making it the fourth-largest city in the state outside of the ...