Burford Station 1905 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Burford () is a town on the

The town centre also has some 15th-century houses and the

The town centre also has some 15th-century houses and the

*

*

Burford – Gateway to the Cotswolds

(Town Council website) *

www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Burford and surrounding area

{{authority control Towns in Oxfordshire Civil parishes in Oxfordshire Cotswolds History of Oxfordshire Paranormal places in the United Kingdom Reportedly haunted locations in South East England West Oxfordshire District

River Windrush

The River Windrush is a tributary of the River Thames in central England. It rises near Winchcombe in Gloucestershire and flows south east for via Burford and Witney to meet the Thames at Newbridge in Oxfordshire.

The river gives its name to t ...

, in the Cotswold

The Cotswolds (, ) is a region in central-southwest England, along a range of rolling hills that rise from the meadows of the upper Thames to an escarpment above the Severn Valley and Evesham Vale.

The area is defined by the bedrock of Jur ...

hills, in the West Oxfordshire

West Oxfordshire is a local government district in northwest Oxfordshire, England, including towns such as Woodstock, Burford, Chipping Norton, Charlbury, Carterton and Witney, where the council is based.

Area

The area is mainly rural downland ...

district of Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primaril ...

, England. It is often referred to as the 'gateway' to the Cotswolds. Burford is located west of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and southeast of Cheltenham

Cheltenham (), also known as Cheltenham Spa, is a spa town and borough on the edge of the Cotswolds in the county of Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort, following the discovery of mineral s ...

, about from the Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

boundary. The toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''toponyms'' ( proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

derives from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

words ''burh

A burh () or burg was an Old English fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new const ...

'' meaning fortified town or hilltown and ''ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

'', the crossing of a river. The 2011 Census recorded the population of Burford parish as 1,422.

Economic and social history

The town began in the middle Saxon period with the founding of a village near the site of the modern priory building. This settlement continued in use until just after theNorman conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqu ...

when the new town of Burford was built. On the site of the old village a hospital was founded which remained open until the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. The modern priory building was constructed some 40 years later, in around 1580.

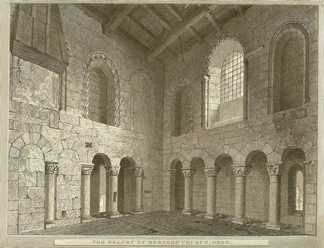

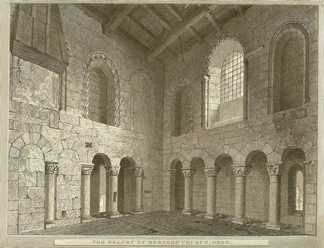

The town centre's most notable building is the Church of St John the Baptist, a Church of England parish church

A parish church in the Church of England is the church which acts as the religious centre for the people within each Church of England parish (the smallest and most basic Church of England administrative unit; since the 19th century sometimes ca ...

, which is a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

. Described by David Verey as "a complicated building which has developed in a curious way from the Norman", it is known for its merchants' guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

chapel, memorial to Henry VIII's barber-surgeon, Edmund Harman

Edmund Harman (c.1509–1577), was the barber-surgeon of Henry VIII of England and a member of his Privy Chamber. He served alongside Thomas Wendy and George Owen.

In February 1536, Harman was made bailiff of Hovington, and given ''the keepin ...

, featuring South American Indians and Kempe stained glass. In 1649 the church was used as a prison during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, when the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

Banbury mutineers were held there. Some of the 340 prisoners left carvings and graffiti, which still survive in the church.

The town centre also has some 15th-century houses and the

The town centre also has some 15th-century houses and the baroque style

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires includin ...

townhouse that is now Burford Methodist Church

Burford Methodist Church is a baroque building in the High Street of Burford, Oxfordshire. It was built between about 1715 and 1730 as a private house and converted in 1849 to a Wesleyan Chapel. It is a Grade II* Listed Building.

Ethos

Baroque ...

. Between the 14th and 17th centuries Burford was important for its wool trade. The Tolsey, midway along Burford's High Street, which was once the focal point for trade, is now a museum. The authors of ''Burford: Buildings and People in a Cotswold Town'' (2008) argue that Burford should be seen as less a medieval town than an Arts and Crafts

A handicraft, sometimes more precisely expressed as artisanal handicraft or handmade, is any of a wide variety of types of work where useful and decorative objects are made completely by one’s hand or by using only simple, non-automated re ...

town. A 2020 article in ''Country Life'' magazine summarized the community's recent history:"Burford, similarly, had bustled during the coaching era, but coaching inns such as Ramping Cat and the Bull were diminished or closed when the railways came. Agriculture remained old-fashioned, if not Biblical, and was badly affected by the long agricultural depression that started in the 1870s. The local dialect was so thick that, in the 1890s, Gibbs had to publish a glossary to explain George Ridler’s Oven, one of the folk songs he collected. In the late 19th century, the Cotswolds assumed a Sleeping Beauty charm, akin to that of Burne-Jones’s Legend of the Briar Rose at Buscot Park in the Thames Valley."

Priory

Burford Priory

Burford Priory is a Grade I listed country house and former priory at Burford in West Oxfordshire, England owned by Elisabeth Murdoch, daughter of Rupert Murdoch, together with Matthew Freud.

History Origin

The house is on the site of a 13t ...

is a country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peop ...

that stands on the site of a 13th-century Augustinian priory hospital. In the 1580s an Elizabethan house was built incorporating remnants of the building. It was remodelled in Jacobean style

The Jacobean style is the second phase of Renaissance architecture in England, following the Elizabethan style. It is named after King James VI and I, with whose reign (1603–1625 in England) it is associated. At the start of James' reign ther ...

, probably after 1637, by which time the estate had been bought by William Lenthall

William Lenthall (1591–1662) was an English politician of the Civil War period. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons for a period of almost twenty years, both before and after the execution of King Charles I.

He is best remembered f ...

, Speaker of the House of Commons in the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

. After 1912 the house and later the chapel were restored for the philanthropist Emslie John Horniman, MP, by the architect Walter Godfrey

Walter Hindes Godfrey, CBE, FSA, FRIBA (1881–1961), was an English architect, antiquary, and architectural and topographical historian. He was also a landscape architect and designer, and an accomplished draftsman and illustrator. He was ...

. From 1949 Burford Priory housed the Society of the Salutation of Mary the Virgin, a community of Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

nuns. In 1987, n declining numbers, it became a mixed community including Church of England Benedictine monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

s. In 2008 the community relocated and sold the property which is now a private dwelling. A ''Time Team

''Time Team'' is a British television programme that originally aired on Channel 4 from 16 January 1994 to 7 September 2014. It returned online in 2022 for two episodes released on YouTube. Created by television producer Tim ...

'' excavation of the Priory in 2010 found pottery sherds from the 12th or 13th century.

English Civil Wars – the Banbury mutiny

On 17 May 1649, three soldiers who were Levellers were executed on the orders ofOliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

in the churchyard at Burford following a mutiny started over pay and the prospect of being sent to fight in Ireland. Corporal Church, Private Perkins, and Cornet Thompson were the key leaders of the mutiny and, after a brief court-martial, were put up against the wall in the churchyard at Burford and shot. The remaining soldiers were pardoned. Each year on the nearest weekend to the Banbury mutiny

The Banbury mutiny was a mutiny by soldiers in the English New Model Army. The mutineers did not achieve all of their aims and some of the leaders were executed shortly afterwards on 17 May 1649.

Background

The mutiny was over pay and politic ...

is commemorated as 'Levellers Day'.

Bell foundry

Burford has twice had abell foundry

Bellfounding is the casting and tuning of large bronze bells in a foundry for use such as in churches, clock towers and public buildings, either to signify the time or an event, or as a musical carillon or chime. Large bells are made by casting ...

: one run by the Neale family in the 17th century and another run by the Bond family in the 19th and 20th centuries. Henry Neale was a bell founder between 1627 and 1641 and also had a foundry at Somerford Keynes

Somerford Keynes (, ) is a village and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England, close to the River Thames and about 5 miles (8 km) from its source. It lies on the boundary with Wiltshire, midway between Cirencester, Swindon and Malmesbury. The ...

in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

. Edward Neale had joined him as a bell-founder at Burford by 1635 and continued the business until 1685. Numerous Neale bells remain in use, including at St Britius, Brize Norton, St Mary's, Buscot, and St James the Great, Fulbrook. A few Neale bells that are no longer rung are displayed in Burford parish church. Henry Bond had a bell foundry at Westcot from 1851 to 1861. He then moved it to Burford where he continued until 1905. He was then succeeded by Thomas Bond, who continued bell-founding at Burford until 1947. Bond bells still in use include four of the ring of six at St John the Evangelist, Taynton, one and a Sanctus bell at St Nicholas, Chadlington and one each at St Mary the Virgin, Chalgrove and St Peter's, Whatcote in Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avo ...

.

Easter Synod

For many years before the 7th century there had been strife between theCeltic Church

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or hel ...

and the Early Church

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

over the question of when Easter Day should be celebrated. The Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

adhered to the rule laid at the Council of Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province ...

in 314, that Easter Day should be the 14th day of the Paschal moon, even if the moon were on a Sunday. The Roman Church had decided that when the 14th day of the Paschal moon was a Sunday, Easter Day should be the Sunday after. Various Synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mean ...

s were held in different parts of the kingdom with the object of settling this controversy, and one was held for this object at Burford in 685. Monk deduces from the fact of the Synod being held at Burford, that the Britons in some numbers had settled in the town and neighbourhood. This Synod was attended by Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary pri ...

, King of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

, and his nephew Berthwald (who had been granted the southern part of his uncle's kingdom); Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Saskatche ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

; Bosel

__NOTOC__

Bosel was a medieval Bishop of Worcester.

Bosel was consecrated bishop in 680. Around 681, he consecrated Kyneburg, a relative of Osric of Hwicce, as the first abbess of Gloucester Abbey, which had been founded by Osric.

Around 685, B ...

, Bishop of Worcester

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

; Seaxwulf

Seaxwulf (before 676 – c. 692) was the founding abbot of the Mercian monastery of Medeshamstede, and an early medieval bishop of Mercia. Very little is known of him beyond these details, drawn from sources such as Bede's ''Ecclesiastical ...

, Bishop of Lichfield

The Bishop of Lichfield is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lichfield in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers 4,516 km2 (1,744 sq. mi.) of the counties of Powys, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire and W ...

; Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the ...

, Abbot of Malmesbury; and many others. Aldhelm was ordered at this conference to write a book against the error of the Britons in the observance of Easter. At this Synod Berthwald gave 40 cassates of land (a cassate is enough land to support a family) to Aldhelm who afterwards became Bishop of Shereborne. According to Spelman, the notes of the Synod were published in 705.

Battle of Burford and the Golden Dragon

Malmesbury and other chroniclers record a battle between theWest Saxons

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

and Mercians at Burford in 752. In the end Æthelhum, the Mercian standard-bearer who carried the flag with a golden dragon

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted a ...

on it, was killed by the lance of his Saxon rival. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'' records "A.D 752. This year Cuthred, king of the West Saxons, in the 12th year of his reign, fought at Burford, against Æthelbald king of the Mercians, and put him to flight." The historian William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Ann ...

(1551–1623) wrote

"... in Saxon Beorgford .e. Burford where Cuthred, king of the West Saxons, then tributary to the Mercians, not being able to endure any longer the cruelty and base exactions of King Æthelbald, met him in the open field with an army and beat him, taking his standard, which was a portraiture of a golden dragon."The origin of the golden dragon standard is attributed to that of

Uther Pendragon

Uther Pendragon ( Brittonic) (; cy, Ythyr Ben Dragwn, Uthyr Pendragon, Uthyr Bendragon), also known as King Uther, was a legendary King of the Britons in sub-Roman Britain (c. 6th century). Uther was also the father of King Arthur.

A few ...

, the father of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

of whom Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography ...

wrote:

ther Pendragon"... ordered two dragons to be fashioned in gold, in the likeness of the one which he had seen in the ray which shone from that star. As soon as the Dragons had been completed this with the most marvellous craftsmanship – he made a present of one of them to the congregation of the cathedral church of the see ofIn the late 16th or early 17th century the people of Burford still celebrated the anniversary of the battle. Camden wrote: "There has been a custom in the town of making a great dragon yearly, and carrying it up and down the streets in great jollity onWinchester Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation .... The second one he kept for himself, so that he could carry it around to his wars."

St John's Eve

Saint John's Eve, starting at sunset on 23 June, is the eve of celebration before the Feast Day of Saint John the Baptist. The Gospel of Luke (Luke 1:26–37, 56–57) states that John was born six months before Jesus; therefore, the feast of J ...

". The field traditionally claimed to be that of the battle is still called Battle Edge

Battle-Edge is a former Field (agriculture), field, located beside Sheep Street and Tanners Lane, in Burford in Oxfordshire, England where Æthelbald of Mercia, King Æthelbald of Mercia was defeated by Cuthred of Wessex, King Cuthred of the West ...

. According to Reverend Francis Knollis' description of the discovery, "On 21 November 1814 a large freestone sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

was discovered near Battle Edge below ground, weighing with the feet pointing almost due south. The interior is long and wide. It was found to contain the remains of a human body, with portions of a leather cuirass

A cuirass (; french: cuirasse, la, coriaceus) is a piece of armour that covers the torso, formed of one or more pieces of metal or other rigid material. The word probably originates from the original material, leather, from the French '' cuirac ...

studded with metal nails. The skeleton was found in near perfect state due to the exclusion of air from the sarcophagus." The coffin is now preserved in Burford churchyard, near the west gate.

"Whose fame is in that dark green tomb? Four stones with their heads of moss stand there. They mark the narrow house of death. Some chief of fame is here! Raise the songs of old! Awake their memory in the tomb." –Ossian Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora'' (1763), and later combined unde ...

Amenities

Burford County Primary School is the town's primary school.Burford School

Burford School is a co-educational academy day and state boarding school located in Burford, Oxfordshire, England. It is one of 40 state boarding schools in England. The school was founded by the Burford Corporation as a grammar school in 1571 ...

, a mixed comprehensive school

A comprehensive school typically describes a secondary school for pupils aged approximately 11–18, that does not select its intake on the basis of academic achievement or aptitude, in contrast to a selective school system where admission is re ...

, is the town's secondary school. The primary school fête

In Britain and some of its former colonies, fêtes are traditional public festivals, held outdoors and organised to raise funds for a charity. They typically include entertainment and the sale of goods and refreshments.

Village fêtes

Village f ...

, held every summer, includes a procession (including a dragon) down High Street to the school, where there are stalls and games. The Blue Cross National Animal Welfare Charity is based at Burford. In September 2001 Burford was twinned with Potenza Picena

Potenza Picena is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Macerata in the Italian region of Marche, about southeast of Ancona and about northeast of Macerata.

''Potentia'' was the Roman town situated in the lower Potenza valley, in the ...

, a small town in the Marche

Marche ( , ) is one of the twenty regions of Italy. In English, the region is sometimes referred to as The Marches ( ). The region is located in the central area of the country, bordered by Emilia-Romagna and the republic of San Marino to the ...

, on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

coast of Italy. In April 2009 Burford was ranked sixth in ''Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine owned by Integrated Whale Media Investments and the Forbes family. Published eight times a year, it features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. ''Forbes'' also r ...

'' magazine's list of "Europe's Most Idyllic Places To Live".

Local legend and literature

Local legend tells of a fiery coach containing the judge and local landowner SirLawrence Tanfield

Sir Lawrence Tanfield (c. 1551 – 30 April 1625) was an English lawyer, politician and Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer. He had a reputation for corruption, and the harshness which he and his wife showed to his tenants was remembered for c ...

of Burford Priory

Burford Priory is a Grade I listed country house and former priory at Burford in West Oxfordshire, England owned by Elisabeth Murdoch, daughter of Rupert Murdoch, together with Matthew Freud.

History Origin

The house is on the site of a 13t ...

and his wife flying around the town that brings a curse upon all who see it. Ross Andrews speculates that the apparition may have been caused by a local tradition of burning effigies of the unpopular couple that began after their deaths. In real life Tanfield and his second wife Elizabeth Evans are known to have been notoriously harsh to their tenants. The visitations were reportedly ended when local clergymen trapped Lady Tanfield's ghost in a corked glass bottle during an exorcism and cast it into the River Windrush. During droughts locals would fill the river from buckets to ensure that the bottle did not rise above the surface and free the spirit. Burford is the main setting for '' The Wool-Pack'', a historical novel for children by Cynthia Harnett

Cynthia Harnett (22 June 1893 – 25 October 1981) was an English author and illustrator, mainly of children's books. She is best known for six historical novels that feature ordinary teenage children involved in events of national significance, ...

. The author J. Meade Falkner, best known for the novel '' Moonfleet'', is buried in the churchyard of St John the Baptist.

Notable people

*

* Elizabeth Cary, Viscountess Falkland

Elizabeth Cary, Viscountess Falkland (''née'' Tanfield; 1585–1639) was an English poet, dramatist, translator, and historian. She is the first woman known to have written and published an original play in English: '' The Tragedy of Mariam''. ...

(1585–1639) poet, dramatist and historian.

* William Lenthall

William Lenthall (1591–1662) was an English politician of the Civil War period. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons for a period of almost twenty years, both before and after the execution of King Charles I.

He is best remembered f ...

(1591–1662 in Burford) politician, Speaker of the House of Commons in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

period.

* Peter Heylyn

Peter Heylyn or Heylin (29 November 1599 – 8 May 1662) was an English ecclesiastic and author of many polemical, historical, political and theological tracts. He incorporated his political concepts into his geographical books ''Microcosmu ...

(1599–1662) ecclesiastic and author of polemical, historical, political and theological tracts.

* Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland

Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland PC (c. 1610 – 20 September 1643) was an English author and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640 to 1642. He fought on the Royalist side in the English Civil War and was killed in action at the ...

(ca.1610–1643) author and politician.

* Marchamont Nedham (1620–1678) journalist, publisher and pamphleteer during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

* Christopher Kempster (1627–1715) master stonemason and architect

* William Beechey

Sir William Beechey (12 December 175328 January 1839) was an English portraitist during the golden age of British painting.

Early life

Beechey was born at Burford, Oxfordshire, on 12 December 1753, the son of William Beechey, a solicitor, an ...

(1753–1839) a leading English portrait painter.

* Charles Henry Newmarch (1824–1903) cleric and author.

* Katharine Mary Briggs

Katharine Mary Briggs (8 November 1898 – 15 October 1980) was a British folklorist and writer, who wrote ''The Anatomy of Puck'', the four-volume ''A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language'', and various other books on fairi ...

(1898–1980) folklorist and writer, lived in Burford

* Edward Mortimer (1943–2021) UN civil servant, journalist, author and academic.

In popular culture

Burford was referred to as Beorgford in ''The Saxon Stories

''The Saxon Stories'' (also known as ''Saxon Tales''/''Saxon Chronicles'' in the US and ''The Warrior Chronicles'' and most recently as ''The Last Kingdom'' series) is a historical novel series written by Bernard Cornwell about the birth of En ...

'' by Bernard Cornwell

Bernard Cornwell (born 23 February 1944) is an English-American author of historical novels and a history of the Waterloo Campaign. He is best known for his novels about Napoleonic Wars rifleman Richard Sharpe. He has also written ''The Saxon ...

.

See also

*Oxford Blue

A blue is an award of sporting colours earned by athletes at some universities and schools for competition at the highest level. The awarding of blues began at Oxford and Cambridge universities in England. They are now awarded at a number of other ...

– a cheese made in Burford

References

Sources

* * translated by Lewis Thorpe. * *External links

Burford – Gateway to the Cotswolds

(Town Council website) *

www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Burford and surrounding area

{{authority control Towns in Oxfordshire Civil parishes in Oxfordshire Cotswolds History of Oxfordshire Paranormal places in the United Kingdom Reportedly haunted locations in South East England West Oxfordshire District