Bulgarian-language Singers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bulgarian (, ; bg, label=none, български, bălgarski, ) is an Eastern South Slavic language spoken in Southeastern Europe, primarily in Bulgaria. It is the language of the Bulgarians.

Along with the closely related

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern  During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic case system, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbors in the Balkan language area (mostly grammatically) and later also by

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic case system, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbors in the Balkan language area (mostly grammatically) and later also by

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the Proto-Slavic yat vowel (Ѣ). This split, which occurred at some point during the Middle Ages, led to the development of Bulgaria's:

*Western dialects (informally called твърд говор/''tvurd govor'' – "hard speech")

**the former ''yat'' is pronounced "e" in all positions. e.g. млеко (''mlekò'') – milk, хлеб (''hleb'') – bread.

*Eastern dialects (informally called мек говор/''mek govor'' – "soft speech")

**the former ''yat'' alternates between "ya" and "e": it is pronounced "ya" if it is under stress and the next syllable does not contain a

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the Proto-Slavic yat vowel (Ѣ). This split, which occurred at some point during the Middle Ages, led to the development of Bulgaria's:

*Western dialects (informally called твърд говор/''tvurd govor'' – "hard speech")

**the former ''yat'' is pronounced "e" in all positions. e.g. млеко (''mlekò'') – milk, хлеб (''hleb'') – bread.

*Eastern dialects (informally called мек говор/''mek govor'' – "soft speech")

**the former ''yat'' alternates between "ya" and "e": it is pronounced "ya" if it is under stress and the next syllable does not contain a

Until the period immediately following the Second World War, all Bulgarian and the majority of foreign linguists referred to the

Until the period immediately following the Second World War, all Bulgarian and the majority of foreign linguists referred to the

, UCLA International Institute Outside Bulgaria and Greece, Macedonian is generally considered an autonomous language within the South Slavic dialect continuum. Sociolinguists agree that the question whether Macedonian is a dialect of Bulgarian or a language is a political one and cannot be resolved on a purely linguistic basis, because dialect continua do not allow for either/or judgements. Nevertheless, Bulgarians often argue that the high degree of mutual intelligibility between Bulgarian and Macedonian proves that they are not different languages, but rather dialects of the same language, whereas Macedonians believe that the differences outweigh the similarities.

In 886 AD, the

In 886 AD, the

' ?

A verb is not always necessary, e.g. when presenting a choice:

* – 'him?'; – 'the yellow one?'The word ('either') has a similar etymological root: и + ли ('and') – e.g. ( – '(either) the yellow one or the red one.

wiktionary

/ref> Rhetorical questions can be formed by adding to a question word, thus forming a "double interrogative" – * – 'Who?'; – 'I wonder who(?)' The same construction +не ('no') is an emphasized positive – * – 'Who was there?' – – 'Nearly everyone!' (lit. 'I wonder who ''wasn't'' there')

Bulgarian at OmniglotBulgarian Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words

(from Wiktionary'

Swadesh list appendix

Information about the linguistic classification of the Bulgarian language (from Glottolog)The linguistic features of the Bulgarian language (from WALS, The World Atlas of Language Structures Online)Information about the Bulgarian language

from the PHOIBLE project.

Locale Data Summary for the Bulgarian language

from Unicode's

Eurodict — multilingual Bulgarian dictionariesRechnik.info — online dictionary of the Bulgarian languageRechko — online dictionary of the Bulgarian languageBulgarian–English–Bulgarian Online dictionary

fro

Bulgarian bilingual dictionariesEnglish, Bulgarian bidirectional dictionary

Courses

Bulgarian for Beginners

UniLang {{DEFAULTSORT:Bulgarian Language Analytic languages Languages of Bulgaria Languages of Greece Languages of Romania Languages of Serbia Languages of North Macedonia Languages of Turkey Languages of Moldova Languages of Ukraine South Slavic languages Subject–verb–object languages Languages written in Cyrillic script

Macedonian language

Macedonian (; , , ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around two million ...

(collectively forming the East South Slavic languages

The Eastern South Slavic dialects form the eastern subgroup of the South Slavic languages. They are spoken mostly in Bulgaria and North Macedonia, and adjacent areas in the neighbouring countries. They form the so-called Balkan Slavic li ...

), it is a member of the Balkan sprachbund and South Slavic dialect continuum of the Indo-European language family. The two languages have several characteristics that set them apart from all other Slavic languages, including the elimination of case declension, the development of a suffixed definite article, and the lack of a verb infinitive. They retain and have further developed the Proto-Slavic verb system (albeit analytically). One such major development is the innovation of evidential

In linguistics, evidentiality is, broadly, the indication of the nature of evidence for a given statement; that is, whether evidence exists for the statement and if so, what kind. An evidential (also verificational or validational) is the particul ...

verb forms to encode for the source of information: witnessed, inferred, or reported.

It is the official language of Bulgaria, and since 2007 has been among the official languages of the European Union. It is also spoken by minorities in several other countries such as Moldova, Ukraine and Serbia.

History

One can divide the development of the Bulgarian language into several periods. * The Prehistoric period covers the time between the Slavic migration to the eastern Balkans ( 6th century CE) and the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia in 860s and the language shift from now extinct Bulgar language. * Old Bulgarian (9th to 11th centuries, also referred to as "Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with Standard language, standardizing the lan ...

") – a literary norm of the early southern dialect of the Proto-Slavic language from which Bulgarian evolved. Saints Cyril and Methodius and their disciples used this norm when translating the Bible and other liturgical literature from Greek into Slavic.

* Middle Bulgarian

Middle Bulgarian language was the lingua franca and the most widely spoken language of the Second Bulgarian Empire. Being descended from Old Bulgarian, Middle Bulgarian eventually developed into modern Bulgarian language by the 16th century.

...

(12th to 15th centuries) – a literary norm that evolved from the earlier Old Bulgarian, after major innovations occurred. A language of rich literary activity, it served as the official administration language of the Second Bulgarian Empire

The Second Bulgarian Empire (; ) was a medieval Bulgarians, Bulgarian state that existed between 1185 and 1396. A successor to the First Bulgarian Empire, it reached the peak of its power under Tsars Kaloyan of Bulgaria, Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II ...

.

* Modern Bulgarian dates from the 16th century onwards, undergoing general grammar and syntax changes in the 18th and 19th centuries. The present-day written Bulgarian language was standardized on the basis of the 19th-century Bulgarian vernacular. The historical development of the Bulgarian language can be described as a transition from a highly synthetic language

A synthetic language uses inflection or agglutination to express Syntax, syntactic relationships within a sentence. Inflection is the addition of morphemes to a root word that assigns grammatical property to that word, while agglutination is the ...

(Old Bulgarian) to a typical analytic language

In linguistic typology, an analytic language is a language that conveys relationships between words in sentences primarily by way of ''helper'' words (particles, prepositions, etc.) and word order, as opposed to using inflections (changing the ...

(Modern Bulgarian) with Middle Bulgarian as a midpoint in this transition.

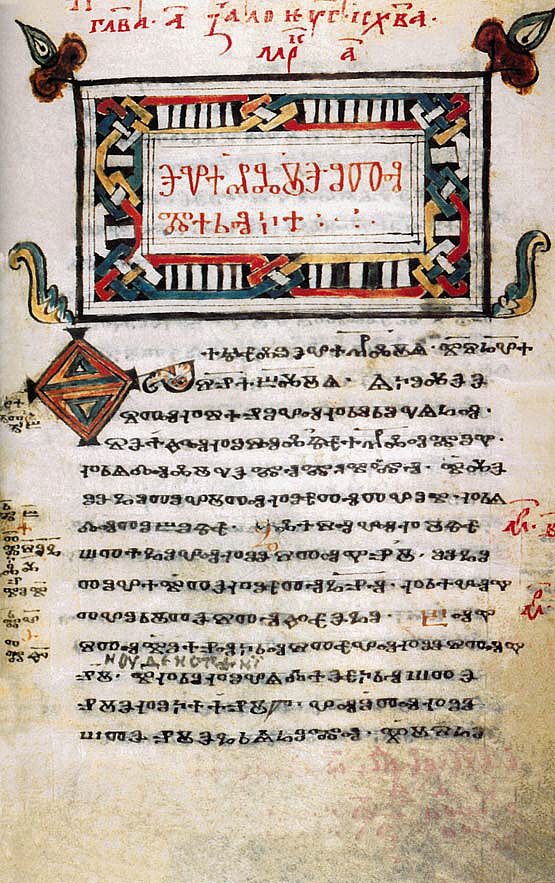

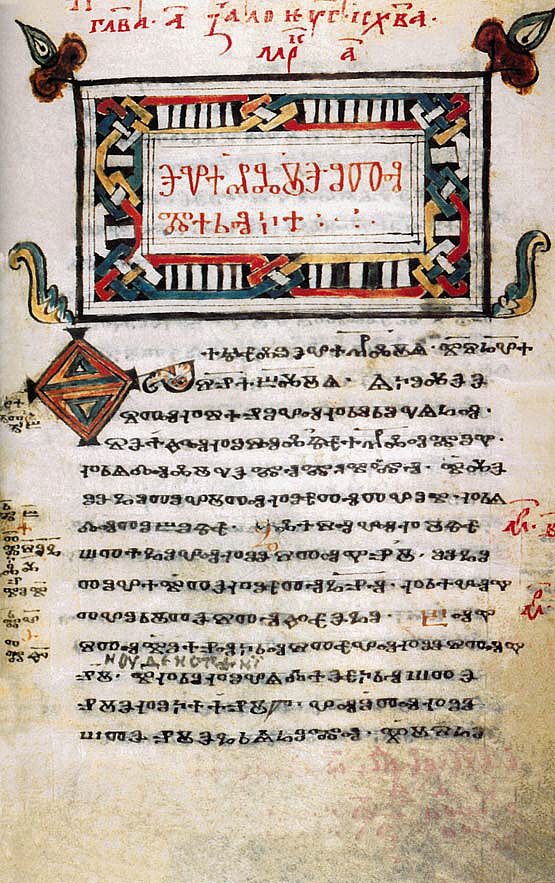

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the Archbishopric of Ohrid in the 11th century, for example in the Greek hagiography of Clement of Ohrid by Theophylact of Ohrid (late 11th century).

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic case system, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbors in the Balkan language area (mostly grammatically) and later also by

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic case system, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbors in the Balkan language area (mostly grammatically) and later also by Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

, which was the official language of the Ottoman Empire, in the form of the Ottoman Turkish language, mostly lexically. As a national revival

National revival or national awakening is a period of ethnic self-consciousness that often precedes a political movement for national liberation but that can take place at a time when independence is politically unrealistic. In the history of Eur ...

occurred toward the end of the period of Ottoman rule (mostly during the 19th century), a modern Bulgarian literary language gradually emerged that drew heavily on Church Slavonic/Old Bulgarian (and to some extent on literary Russian, which had preserved many lexical items from Church Slavonic) and later reduced the number of Turkish and other Balkan loans. Today one difference between Bulgarian dialects in the country and literary spoken Bulgarian is the significant presence of Old Bulgarian words and even word forms in the latter. Russian loans are distinguished from Old Bulgarian ones on the basis of the presence of specifically Russian phonetic changes, as in оборот (turnover, rev), непонятен (incomprehensible), ядро (nucleus) and others. Many other loans from French, English and the classical languages have subsequently entered the language as well.

Modern Bulgarian was based essentially on the Eastern dialects of the language, but its pronunciation is in many respects a compromise between East and West Bulgarian (see especially the phonetic sections below). Following the efforts of some figures of the National awakening of Bulgaria (most notably Neofit Rilski and Ivan Bogorov

Ivan Bogorov ( bg, Иван Богоров) (1818–1892) was a noted Bulgarian encyclopedist from the time of the National Revival. Educated in medicine, he also worked in the spheres of industry, economy, transport, geography, journalism and ...

), there had been many attempts to codify a standard Bulgarian language; however, there was much argument surrounding the choice of norms. Between 1835 and 1878 more than 25 proposals were put forward and "linguistic chaos" ensued.Glanville Price. ''Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000), p.45 Eventually the eastern dialects prevailed,

Victor Roudometof. ''Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian question'' (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002), p. 92

and in 1899 the Bulgarian Ministry of Education officially codified a standard Bulgarian language based on the Drinov-Ivanchev orthography.

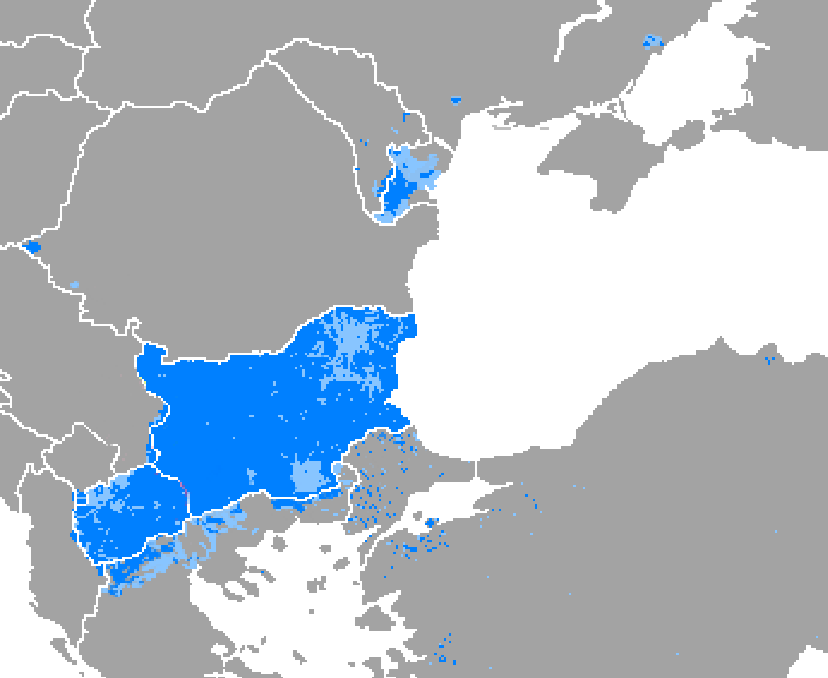

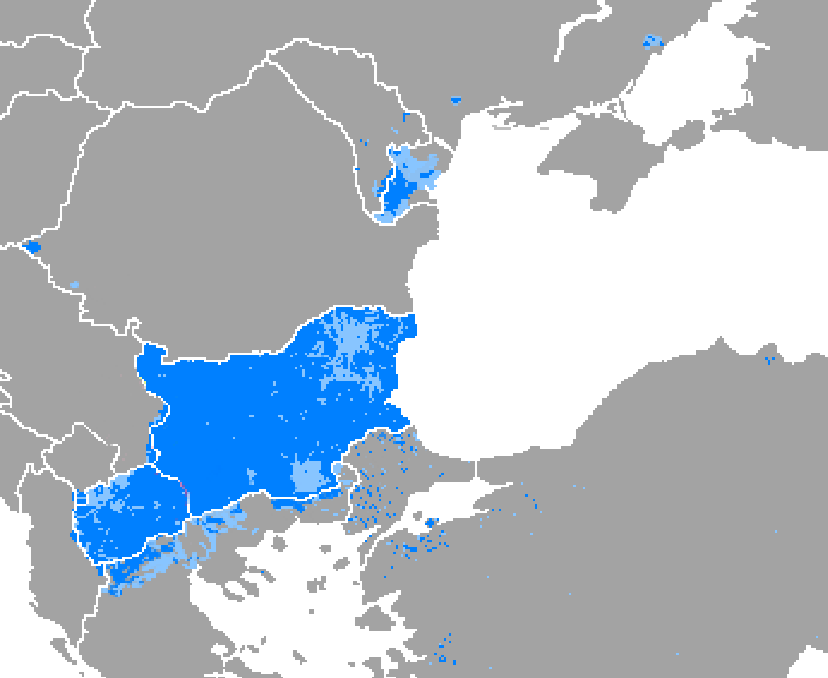

Geographic distribution

Bulgarian is the official language of Bulgaria, where it is used in all spheres of public life. As of 2011, it is spoken as a first language by about 6million people in the country, or about four out of every five Bulgarian citizens. Of the 6.64 million people who answered the optional language question in the 2011 census, 5.66 million (or 85.2%) reported being native speakers of Bulgarian (this amounts to 76.8% of the total population of 7.36 million). There is also a significant Bulgarian diaspora abroad. One of the main historically established communities are the Bessarabian Bulgarians, whose settlement in theBessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

region of nowadays Moldavia and Ukraine dates mostly to the early 19th century. There were Bulgarian speakers in Ukraine at the 2001 census, in Moldova as of the 2014 census (of which were habitual users of the language), and presumably a significant proportion of the 13,200 ethnic Bulgarians residing in neighbouring Transnistria in 2016.

Another community abroad are the Banat Bulgarians, who migrated in the 17th century to the Banat region now split between Romania, Serbia and Hungary. They speak the Banat Bulgarian dialect, which has had its own written standard and a historically important literary tradition.

There are Bulgarian speakers in neighbouring countries as well. The regional dialects of Bulgarian and Macedonian form a dialect continuum, and there is no well-defined boundary where one language ends and the other begins. Within the limits of the Republic of North Macedonia a strong separate Macedonian identity has emerged since the Second World War, even though there still are a small number of citizens who identify their language as Bulgarian. Beyond the borders of North Macedonia, the situation is more fluid, and the pockets of speakers of the related regional dialects in Albania and in Greece variously identify their language as Macedonian or as Bulgarian. In Serbia, there were speakers as of 2011, mainly concentrated in the so-called Western Outlands along the border with Bulgaria. Bulgarian is also spoken in Turkey: natively by Pomaks, and as a second language by many Bulgarian Turks who emigrated from Bulgaria, mostly during the "Big Excursion" of 1989.

The language is also represented among the diaspora in Western Europe and North America, which has been steadily growing since the 1990s. Countries with significant numbers of speakers include Germany, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom ( speakers in England and Wales as of 2011), France, the United States, and Canada ( in 2011).

Dialects

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the Proto-Slavic yat vowel (Ѣ). This split, which occurred at some point during the Middle Ages, led to the development of Bulgaria's:

*Western dialects (informally called твърд говор/''tvurd govor'' – "hard speech")

**the former ''yat'' is pronounced "e" in all positions. e.g. млеко (''mlekò'') – milk, хлеб (''hleb'') – bread.

*Eastern dialects (informally called мек говор/''mek govor'' – "soft speech")

**the former ''yat'' alternates between "ya" and "e": it is pronounced "ya" if it is under stress and the next syllable does not contain a

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the Proto-Slavic yat vowel (Ѣ). This split, which occurred at some point during the Middle Ages, led to the development of Bulgaria's:

*Western dialects (informally called твърд говор/''tvurd govor'' – "hard speech")

**the former ''yat'' is pronounced "e" in all positions. e.g. млеко (''mlekò'') – milk, хлеб (''hleb'') – bread.

*Eastern dialects (informally called мек говор/''mek govor'' – "soft speech")

**the former ''yat'' alternates between "ya" and "e": it is pronounced "ya" if it is under stress and the next syllable does not contain a front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

(''e'' or ''i'') – e.g. мляко (''mlyàko''), хляб (''hlyab''), and "e" otherwise – e.g. млекар (''mlekàr'') – milkman, хлебар (''hlebàr'') – baker. This rule obtains in most Eastern dialects, although some have "ya", or a special "open e" sound, in all positions.

The literary language norm, which is generally based on the Eastern dialects, also has the Eastern alternating reflex of ''yat''. However, it has not incorporated the general Eastern umlaut of ''all'' synchronic or even historic "ya" sounds into "e" before front vowels – e.g. поляна (''polyana'') vs. полени (''poleni'') "meadow – meadows" or even жаба (''zhaba'') vs. жеби (''zhebi'') "frog – frogs", even though it co-occurs with the yat alternation in almost all Eastern dialects that have it (except a few dialects along the yat border, e.g. in the Pleven

Pleven ( bg, Плèвен ) is the seventh most populous city in Bulgaria. Located in the northern part of the country, it is the administrative centre of Pleven Province, as well as of the subordinate Pleven municipality. It is the biggest ...

region).

More examples of the ''yat'' umlaut in the literary language are:

*''mlyàko'' (milk) .→ ''mlekàr'' (milkman); ''mlèchen'' (milky), etc.

*''syàdam'' (sit) b.→ ''sedàlka'' (seat); ''sedàlishte'' (seat, e.g. of government or institution, butt), etc.

*''svyat'' (holy) dj.

A DJ or disc jockey is a person who plays recorded music for an audience.

DJ may also refer to:

Businesses

* Dow Jones Industrial Average, a stock market index

* Dansk Jernbane, a Danish freight company

* David Jones Limited, an Australian ret ...

→ ''svetètz'' (saint); ''svetìlishte'' (sanctuary), etc. (in this example, ''ya/e'' comes not from historical ''yat'' but from ''small yus ''(ѧ), which normally becomes ''e'' in Bulgarian, but the word was influenced by Russian and the ''yat'' umlaut)

Until 1945, Bulgarian orthography did not reveal this alternation and used the original Old Slavic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and using it in translating the Bible and other ...

Cyrillic

, bg, кирилица , mk, кирилица , russian: кириллица , sr, ћирилица, uk, кирилиця

, fam1 = Egyptian hieroglyphs

, fam2 = Proto-Sinaitic

, fam3 = Phoenician

, fam4 = G ...

letter ''yat'' (Ѣ), which was commonly called двойно е (''dvoyno e'') at the time, to express the historical ''yat'' vowel or at least root vowels displaying the ''ya – e'' alternation. The letter was used in each occurrence of such a root, regardless of the actual pronunciation of the vowel: thus, both ''mlyako'' and ''mlekar'' were spelled with (Ѣ). Among other things, this was seen as a way to "reconcile" the Western and the Eastern dialects and maintain language unity at a time when much of Bulgaria's Western dialect area was controlled by Serbia and Greece, but there were still hopes and occasional attempts to recover it. With the 1945 orthographic reform, this letter was abolished and the present spelling was introduced, reflecting the alternation in pronunciation.

This had implications for some grammatical constructions:

*The third person plural pronoun and its derivatives. Before 1945 the pronoun "they" was spelled тѣ (''tě''), and its derivatives took this as the root. After the orthographic change, the pronoun and its derivatives were given an equal share of soft and hard spellings:

**"they" – те (''te'') → "them" – тях (''tyah'');

**"their(s)" – ''tehen'' (masc.); ''tyahna'' (fem.); ''tyahno'' (neut.); ''tehni'' (plur.)

*adjectives received the same treatment as тѣ:

**"whole" – ''tsyal'' → "the whole...": ''tseliyat'' (masc.); ''tsyalata'' (fem.); ''tsyaloto'' (neut.); ''tselite'' (plur.)

Sometimes, with the changes, words began to be spelled as other words with different meanings, e.g.:

*свѣт (''svět'') – "world" became свят (''svyat''), spelt and pronounced the same as свят – "holy".

*тѣ (''tě'') – "they" became те (''te'').

In spite of the literary norm regarding the yat vowel, many people living in Western Bulgaria, including the capital Sofia, will fail to observe its rules. While the norm requires the realizations ''vidyal'' vs. ''videli'' (he has seen; they have seen), some natives of Western Bulgaria will preserve their local dialect pronunciation with "e" for all instances of "yat" (e.g. ''videl'', ''videli''). Others, attempting to adhere to the norm, will actually use the "ya" sound even in cases where the standard language has "e" (e.g. ''vidyal'', ''vidyali''). The latter hypercorrection

In sociolinguistics, hypercorrection is non-standard use of language that results from the over-application of a perceived rule of language-usage prescription. A speaker or writer who produces a hypercorrection generally believes through a mi ...

is called свръхякане (''svrah-yakane'' ≈"over-''ya''-ing").

;Shift from to

Bulgarian is the only Slavic language whose literary standard does not naturally contain the iotated

In Slavic languages, iotation (, ) is a form of palatalization that occurs when a consonant comes into contact with a palatal approximant from the succeeding phoneme. The is represented by iota (ι) in the Cyrillic alphabet and the Greek alphab ...

sound (or its palatalized variant , except in non-Slavic foreign-loaned words). The sound is common in all modern Slavic languages (e.g. Czech ''medvěd'' "bear", Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

''pięć'' "five", Serbo-Croatian ''jelen'' "deer", Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

''немає'' "there is not...", Macedonian

Macedonian most often refers to someone or something from or related to Macedonia.

Macedonian(s) may specifically refer to:

People Modern

* Macedonians (ethnic group), a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group primarily associated with North M ...

''пишување'' "writing", etc.), as well as some Western Bulgarian dialectal forms – e.g. ''ора̀н’е'' (standard Bulgarian: ''оране'' , "ploughing"), however it is not represented in standard Bulgarian speech or writing. Even where occurs in other Slavic words, in Standard Bulgarian it is usually transcribed and pronounced as pure – e.g. Boris Yeltsin is "Eltsin" ( Борис Елцин), Yekaterinburg is "Ekaterinburg" ( Екатеринбург) and Sarajevo is "Saraevo" ( Сараево), although - because the sound is contained in a stressed syllable at the beginning of the word - Jelena Janković is "Yelena" – Йелена Янкович.

Relationship to Macedonian

Until the period immediately following the Second World War, all Bulgarian and the majority of foreign linguists referred to the

Until the period immediately following the Second World War, all Bulgarian and the majority of foreign linguists referred to the South Slavic dialect continuum

The South Slavic languages are one of three branches of the Slavic languages. There are approximately 30 million speakers, mainly in the Balkans. These are separated geographically from speakers of the other two Slavic branches (West and East) ...

spanning the area of modern Bulgaria, North Macedonia and parts of Northern Greece as a group of Bulgarian dialects.Mazon, Andre. ''Contes Slaves de la Macédoine Sud-Occidentale: Etude linguistique; textes et traduction''; Notes de Folklore, Paris 1923, p. 4. In contrast, Serbian sources tended to label them "south Serbian" dialects. Some local naming conventions included ''bolgárski'', ''bugárski'' and so forth. The codifiers of the standard Bulgarian language, however, did not wish to make any allowances for a pluricentric

A pluricentric language or polycentric language is a language with several interacting codified standard language, standard forms, often corresponding to different countries. Many examples of such languages can be found worldwide among the most-spo ...

"Bulgaro-Macedonian" compromise. In 1870 Marin Drinov, who played a decisive role in the standardization of the Bulgarian language, rejected the proposal of Parteniy Zografski

Parteniy Zografski or Parteniy Nishavski ( bg, Партений Зографски/Нишавски; mk, Партенија Зографски; 1818 – February 7, 1876) was a 19th-century Bulgarian cleric, philologist, and folklorist from G ...

and Kuzman Shapkarev for a mixed eastern and western Bulgarian/Macedonian foundation of the standard Bulgarian language, stating in his article in the newspaper Makedoniya: "Such an artificial assembly of written language is something impossible, unattainable and never heard of."

After 1944 the People's Republic of Bulgaria and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia began a policy of making Macedonia into the connecting link for the establishment of a new Balkan Federative Republic and stimulating here a development of distinct Macedonian

Macedonian most often refers to someone or something from or related to Macedonia.

Macedonian(s) may specifically refer to:

People Modern

* Macedonians (ethnic group), a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group primarily associated with North M ...

consciousness. With the proclamation of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia as part of the Yugoslav federation, the new authorities also started measures that would overcome the pro-Bulgarian feeling among parts of its population and in 1945 a separate Macedonian language

Macedonian (; , , ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around two million ...

was codified. After 1958, when the pressure from Moscow decreased, Sofia reverted to the view that the Macedonian language did not exist as a separate language. Nowadays, Bulgarian and Greek linguists, as well as some linguists from other countries, still consider the various Macedonian dialects as part of the broader Bulgarian pluricentric dialectal continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated variet ...

.Language profile Macedonian, UCLA International Institute Outside Bulgaria and Greece, Macedonian is generally considered an autonomous language within the South Slavic dialect continuum. Sociolinguists agree that the question whether Macedonian is a dialect of Bulgarian or a language is a political one and cannot be resolved on a purely linguistic basis, because dialect continua do not allow for either/or judgements. Nevertheless, Bulgarians often argue that the high degree of mutual intelligibility between Bulgarian and Macedonian proves that they are not different languages, but rather dialects of the same language, whereas Macedonians believe that the differences outweigh the similarities.

Alphabet

In 886 AD, the

In 886 AD, the Bulgarian Empire

In the medieval history of Europe, Bulgaria's status as the Bulgarian Empire ( bg, Българско царство, ''Balgarsko tsarstvo'' ) occurred in two distinct periods: between the seventh and the eleventh centuries and again between the ...

introduced the Glagolitic alphabet which was devised by the Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 850s. The Glagolitic alphabet was gradually superseded in later centuries by the Cyrillic script, developed around the Preslav Literary School, Bulgaria in the late 9th century.

Several Cyrillic alphabets with 28 to 44 letters were used in the beginning and the middle of the 19th century during the efforts on the codification of Modern Bulgarian until an alphabet with 32 letters, proposed by Marin Drinov, gained prominence in the 1870s. The alphabet of Marin Drinov was used until the orthographic reform of 1945, when the letters yat (uppercase Ѣ, lowercase ѣ) and yus

Little yus (Ѧ ѧ) and big yus (Ѫ ѫ), or jus, are letters of the Cyrillic, Cyrillic script representing two Proto-Slavic, Common Slavonic nasal vowels in the early Cyrillic alphabet, early Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet, Glagolitic ...

(uppercase Ѫ, lowercase ѫ) were removed from its alphabet, reducing the number of letters to 30.

With the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union

On 1 January 2007, Bulgaria and Romania became member states of the European Union (EU) in the fifth wave of EU enlargement.

Negotiations

Romania was the first country of post-communist Europe to have official relations with the European Comm ...

on 1 January 2007, Cyrillic became the third official script of the European Union, following the Latin and Greek script

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BCE. It is derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and was the earliest known alphabetic script to have distinct letters for vowels as we ...

s.

Phonology

Bulgarian possesses a phonology similar to that of the rest of the South Slavic languages, notably lacking Serbo-Croatian's phonemic vowel length and tones and alveo-palatal affricates. The eastern dialects exhibit palatalization of consonants before front vowels ( and ) and reduction of vowel phonemes in unstressed position (causing mergers of and , and , and ) - both patterns have partial parallels in Russian and lead to a partly similar sound. The western dialects are like Macedonian and Serbo-Croatian in that they do not have allophonic palatalization and have only little vowel reduction. Bulgarian has six vowel phonemes, but at least eight distinct phones can be distinguished when reduced allophones are taken into consideration.Grammar

The parts of speech in Bulgarian are divided in ten types, which are categorized in two broad classes: mutable and immutable. The difference is that mutable parts of speech vary grammatically, whereas the immutable ones do not change, regardless of their use. The five classes of mutables are: ''nouns'', ''adjectives'', ''numerals'', ''pronouns'' and ''verbs''. Syntactically, the first four of these form the group of the noun or the nominal group. The immutables are: ''adverbs'', ''prepositions'', ''conjunctions'', ''particles'' and ''interjections''. Verbs and adverbs form the group of the verb or the verbal group.Nominal morphology

Nouns and adjectives have the categories grammatical gender, number,case

Case or CASE may refer to:

Containers

* Case (goods), a package of related merchandise

* Cartridge case or casing, a firearm cartridge component

* Bookcase, a piece of furniture used to store books

* Briefcase or attaché case, a narrow box to c ...

(only vocative) and definiteness in Bulgarian. Adjectives and adjectival pronouns agree with nouns in number and gender. Pronouns have gender and number and retain (as in nearly all Indo-European languages) a more significant part of the case system.

Nominal inflection

=Gender

= There are three grammatical genders in Bulgarian: ''masculine'', ''feminine'' and ''neuter''. The gender of the noun can largely be inferred from its ending: nouns ending in a consonant ("zero ending") are generally masculine (for example, 'city', 'son', 'man'; those ending in –а/–я (-a/-ya) ( 'woman', 'daughter', 'street') are normally feminine; and nouns ending in –е, –о are almost always neuter ( 'child', 'lake'), as are those rare words (usually loanwords) that end in –и, –у, and –ю ( ' tsunami', 'taboo', 'menu'). Perhaps the most significant exception from the above are the relatively numerous nouns that end in a consonant and yet are feminine: these comprise, firstly, a large group of nouns with zero ending expressing quality, degree or an abstraction, including all nouns ending on –ост/–ест -=Number

= Two numbers are distinguished in Bulgarian–singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular homology

* SINGULAR, an open source Computer Algebra System (CAS)

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, ...

and plural. A variety of plural suffixes is used, and the choice between them is partly determined by their ending in singular and partly influenced by gender; in addition, irregular declension and alternative plural forms are common. Words ending in (which are usually feminine) generally have the plural ending , upon dropping of the singular ending. Of nouns ending in a consonant, the feminine ones also use , whereas the masculine ones usually have for polysyllables and for monosyllables (however, exceptions are especially common in this group). Nouns ending in (most of which are neuter) mostly use the suffixes (both of which require the dropping of the singular endings) and .

With cardinal numbers and related words such as ('several'), masculine nouns use a special count form in , which stems from the Proto-Slavonic dual

Dual or Duals may refer to:

Paired/two things

* Dual (mathematics), a notion of paired concepts that mirror one another

** Dual (category theory), a formalization of mathematical duality

*** see more cases in :Duality theories

* Dual (grammatical ...

: ('two/three chairs') versus ('these chairs'); cf. feminine ('two/three/these books') and neuter ('two/three/these beds'). However, a recently developed language norm requires that count forms should only be used with masculine nouns that do not denote persons. Thus, ('two/three students') is perceived as more correct than , while the distinction is retained in cases such as ('two/three pencils') versus ('these pencils').

=Case

= Cases exist only in thepersonal

Personal may refer to:

Aspects of persons' respective individualities

* Privacy

* Personality

* Personal, personal advertisement, variety of classified advertisement used to find romance or friendship

Companies

* Personal, Inc., a Washington, ...

and some other pronouns (as they do in many other modern Indo-European languages), with nominative

In grammar, the nominative case (abbreviated ), subjective case, straight case or upright case is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb or (in Latin and formal variants of Engl ...

, accusative, dative

In grammar, the dative case (abbreviated , or sometimes when it is a core argument) is a grammatical case used in some languages to indicate the recipient or beneficiary of an action, as in "Maria Jacobo potum dedit", Latin for "Maria gave Jacob a ...

and vocative forms. Vestiges are present in a number of phraseological units and sayings. The major exception are vocative forms, which are still in use for masculine (with the endings -е, -о and -ю) and feminine nouns (- �/й� and -е) in the singular.

=Definiteness (article)

= In modern Bulgarian, definiteness is expressed by a definite article which is postfixed to the noun, much like in the Scandinavian languages orRomanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

(indefinite: , 'person'; definite: , "''the'' person") or to the first nominal constituent of definite noun phrases (indefinite: , 'a good person'; definite: , "''the'' good person"). There are four singular definite articles. Again, the choice between them is largely determined by the noun's ending in the singular. Nouns that end in a consonant and are masculine use –ът/–ят, when they are grammatical subjects, and –а/–я elsewhere. Nouns that end in a consonant and are feminine, as well as nouns that end in –а/–я (most of which are feminine, too) use –та. Nouns that end in –е/–о use –то.

The plural definite article is –те for all nouns except for those whose plural form ends in –а/–я; these get –та instead. When postfixed to adjectives the definite articles are –ят/–я for masculine gender (again, with the longer form being reserved for grammatical subjects), –та for feminine gender, –то for neuter gender, and –те for plural.

Adjective and numeral inflection

Both groups agree in gender and number with the noun they are appended to. They may also take the definite article as explained above.Pronouns

Pronouns may vary in gender, number, and definiteness, and are the only parts of speech that have retained case inflections. Three cases are exhibited by some groups of pronouns – nominative, accusative and dative. The distinguishable types of pronouns include the following: personal, relative, reflexive, interrogative, negative, indefinitive, summative and possessive.Verbal morphology and grammar

The Bulgarian verb can take up to 3,000 distinct forms, as it varies in person, number, voice, aspect, mood, tense and in some cases gender.Finite verbal forms

Finite verbal forms are ''simple'' or ''compound'' and agree with subjects in person (first, second and third) and number (singular, plural). In addition to that, past compound forms using participles vary in gender (masculine, feminine, neuter) and voice (active and passive) as well as aspect (perfective/aorist and imperfective).Aspect

Bulgarian verbs express lexical aspect: perfective verbs signify the completion of the action of the verb and form past perfective (aorist) forms; imperfective ones are neutral with regard to it and form past imperfective forms. Most Bulgarian verbs can be grouped in perfective-imperfective pairs (imperfective/perfective: "come", "arrive"). Perfective verbs can be usually formed from imperfective ones by suffixation or prefixation, but the resultant verb often deviates in meaning from the original. In the pair examples above, aspect is stem-specific and therefore there is no difference in meaning. In Bulgarian, there is alsogrammatical aspect

In linguistics, aspect is a grammatical category that expresses how an action, event, or state, as denoted by a verb, extends over time. Perfective aspect is used in referring to an event conceived as bounded and unitary, without reference to ...

. Three grammatical aspects are distinguishable: neutral, perfect and pluperfect. The neutral aspect comprises the three simple tenses and the future tense. The pluperfect is manifest in tenses that use double or triple auxiliary "be" participles like the past pluperfect subjunctive. Perfect constructions use a single auxiliary "be".

Mood

The traditional interpretation is that in addition to the four moods (наклонения ) shared by most other European languages – indicative (изявително, ) imperative (повелително ),subjunctive

The subjunctive (also known as conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of the utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude towards it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality ...

( ) and conditional

Conditional (if then) may refer to:

* Causal conditional, if X then Y, where X is a cause of Y

* Conditional probability, the probability of an event A given that another event B has occurred

*Conditional proof, in logic: a proof that asserts a ...

(условно, ) – in Bulgarian there is one more to describe a general category of unwitnessed events – the inferential (преизказно ) mood. However, most contemporary Bulgarian linguists usually exclude the subjunctive mood and the inferential mood from the list of Bulgarian moods (thus placing the number of Bulgarian moods at a total of 3: indicative, imperative and conditional) and don't consider them to be moods but view them as verbial morphosyntactic constructs or separate grameme

A grammeme in linguistics is a unit of grammar, just as a lexeme is a lexical unit and a morpheme is a morphological unit. (See emic unit.)

More specifically, a grammeme is a value of a grammatical category. For example, singular and plural are ...

s of the verb class. The possible existence of a few other moods has been discussed in the literature. Most Bulgarian school grammars teach the traditional view of 4 Bulgarian moods (as described above, but excluding the subjunctive and including the inferential).

Tense

There are three grammatically distinctive positions in time – present, past and future – which combine with aspect and mood to produce a number of formations. Normally, in grammar books these formations are viewed as separate tenses – i. e. "past imperfect" would mean that the verb is in past tense, in the imperfective aspect, and in the indicative mood (since no other mood is shown). There are more than 40 different tenses across Bulgarian's two aspects and five moods. In the indicative mood, there are three simple tenses: *''Present tense'' is a temporally unmarked simple form made up of the verbal stem and a complex suffix composed of thethematic vowel

In Indo-European studies, a thematic vowel or theme vowel is the vowel or from ablaut placed before the ending of a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word. Nouns, adjectives, and verbs in the Indo-European languages with this vowel are thematic, and tho ...

, or and the person/number ending (, , "I arrive/I am arriving"); only imperfective verbs can stand in the present indicative tense independently;

*''Past imperfect'' is a simple verb form used to express an action which is contemporaneous or subordinate to other past actions; it is made up of an imperfective or a perfective verbal stem and the person/number ending ( , , 'I was arriving');

*''Past aorist'' is a simple form used to express a temporarily independent, specific past action; it is made up of a perfective or an imperfective verbal stem and the person/number ending (, , 'I arrived', , , 'I read');

In the indicative there are also the following compound tenses:

*''Future tense'' is a compound form made of the particle and present tense ( , 'I will study'); negation is expressed by the construction and present tense ( , or the old-fashioned form , 'I will not study');

*''Past future tense'' is a compound form used to express an action which was to be completed in the past but was future as regards another past action; it is made up of the past imperfect of the verb ('will'), the particle ('to') and the present tense of the verb (e.g. , , 'I was going to study');

*''Present perfect'' is a compound form used to express an action which was completed in the past but is relevant for or related to the present; it is made up of the present tense of the verb съм ('be') and the past participle (e.g. , 'I have studied');

*''Past perfect'' is a compound form used to express an action which was completed in the past and is relative to another past action; it is made up of the past tense of the verb съм and the past participle (e.g. , 'I had studied');

*''Future perfect'' is a compound form used to express an action which is to take place in the future before another future action; it is made up of the future tense of the verb съм and the past participle (e.g. , 'I will have studied');

*''Past future perfect'' is a compound form used to express a past action which is future with respect to a past action which itself is prior to another past action; it is made up of the past imperfect of , the particle the present tense of the verb съм and the past participle of the verb (e.g. , , 'I would have studied').

The four perfect constructions above can vary in aspect depending on the aspect of the main-verb participle; they are in fact pairs of imperfective and perfective aspects. Verbs in forms using past participles also vary in voice and gender.

There is only one simple tense in the imperative mood, the present, and there are simple forms only for the second-person singular, -и/-й (-i, -y/i), and plural, -ете/-йте (-ete, -yte), e.g. уча ('to study'): , sg., , pl.; 'to play': , . There are compound imperative forms for all persons and numbers in the present compound imperative (, ), the present perfect compound imperative (, ) and the rarely used present pluperfect compound imperative (, ).

The conditional mood consists of five compound tenses, most of which are not grammatically distinguishable. The present, future and past conditional use a special past form of the stem би- (bi – "be") and the past participle (, , 'I would study'). The past future conditional and the past future perfect conditional coincide in form with the respective indicative tenses.

The subjunctive mood

The subjunctive (also known as conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of the utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude towards it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality ...

is rarely documented as a separate verb form in Bulgarian, (being, morphologically, a sub-instance of the quasi- infinitive construction with the particle да and a normal finite verb form), but nevertheless it is used regularly. The most common form, often mistaken for the present tense, is the present subjunctive ( , 'I had better go'). The difference between the present indicative and the present subjunctive tense is that the subjunctive can be formed by ''both'' perfective and imperfective verbs. It has completely replaced the infinitive and the supine from complex expressions (see below). It is also employed to express opinion about ''possible'' future events. The past perfect subjunctive ( , 'I'd had better be gone') refers to ''possible'' events in the past, which ''did not'' take place, and the present pluperfect subjunctive ( ), which may be used about both past and future events arousing feelings of incontinence, suspicion, etc.

The inferential mood has five pure tenses. Two of them are simple – ''past aorist inferential'' and ''past imperfect inferential'' – and are formed by the past participles of perfective and imperfective verbs, respectively. There are also three compound tenses – ''past future inferential'', ''past future perfect inferential'' and ''past perfect inferential''. All these tenses' forms are gender-specific in the singular. There are also conditional and compound-imperative crossovers. The existence of inferential forms has been attributed to Turkic influences by most Bulgarian linguists. Morphologically, they are derived from the perfect

Perfect commonly refers to:

* Perfection, completeness, excellence

* Perfect (grammar), a grammatical category in some languages

Perfect may also refer to:

Film

* Perfect (1985 film), ''Perfect'' (1985 film), a romantic drama

* Perfect (2018 f ...

.

Non-finite verbal forms

Bulgarian has the following participles: *''Present active participle'' (сегашно деятелно причастие) is formed from imperfective stems with the addition of the suffixes –ащ/–ещ/–ящ (четящ, 'reading') and is used only attributively; *''Present passive participle'' (сегашно страдателно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffixes -им/аем/уем (четим, 'that can be read, readable'); *''Past active aorist participle'' (минало свършено деятелно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffix –л– to perfective stems (чел, ' averead'); *''Past active imperfect participle'' (минало несвършено деятелно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffixes –ел/–ал/–ял to imperfective stems (четял, 'ave been

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE se ...

reading');

*''Past passive aorist participle (минало свършено страдателно причастие) is formed from aorist/perfective stems with the addition of the suffixes -н/–т (прочетен, 'read'; убит, 'killed'); it is used predicatively and attributively;

*''Past passive imperfect participle (минало несвършено страдателно причастие) is formed from imperfective stems with the addition of the suffix –н (прочитан, 'een

Een ːnis a village in the Netherlands. It is part of the Noordenveld municipality in Drenthe.

History

Een is an ''esdorp'' which developed in the middle ages on the higher grounds. The communal pasture is triangular. The village developed dur ...

read'; убиван, 'een

Een ːnis a village in the Netherlands. It is part of the Noordenveld municipality in Drenthe.

History

Een is an ''esdorp'' which developed in the middle ages on the higher grounds. The communal pasture is triangular. The village developed dur ...

being killed'); it is used predicatively and attributively;

*'' Adverbial participle'' (деепричастие) is usually formed from imperfective present stems with the suffix –(е)йки (четейки, 'while reading'), relates an action contemporaneous with and subordinate to the main verb and is originally a Western Bulgarian form.

The participles are inflected by gender, number, and definiteness, and are coordinated with the subject when forming compound tenses (see tenses above). When used in an attributive role, the inflection attributes are coordinated with the noun that is being attributed.

Reflexive verbs

Bulgarian uses reflexive verbal forms (i.e. actions which are performed by theagent

Agent may refer to:

Espionage, investigation, and law

*, spies or intelligence officers

* Law of agency, laws involving a person authorized to act on behalf of another

** Agent of record, a person with a contractual agreement with an insuranc ...

onto him- or herself) which behave in a similar way as they do in many other Indo-European languages, such as French and Spanish. The reflexive is expressed by the invariable particle ''se'',Unlike in French and Spanish, where ''se'' is only used for the 3rd person, and other particles, such as ''me'' and ''te'', are used for the 1st and 2nd persons singular, e.g. ''je me lave/me lavo'' – I wash myself. originally a clitic

In morphology and syntax, a clitic (, backformed from Greek "leaning" or "enclitic"Crystal, David. ''A First Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics''. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980. Print.) is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a w ...

form of the accusative reflexive pronoun. Thus –

*''miya'' – I wash, ''miya se'' – I wash myself, ''miesh se'' – you wash yourself

*''pitam'' – I ask, ''pitam se'' – I ask myself, ''pitash se'' – you ask yourself

When the action is performed on others, other particles are used, just like in any normal verb, e.g. –

*''miya te'' – I wash you

*''pitash me'' – you ask me

Sometimes, the reflexive verb form has a similar but not necessarily identical meaning to the non-reflexive verb –

*''kazvam'' – I say, ''kazvam se'' – my name is (lit. "I call myself")

*''vizhdam'' – I see, ''vizhdame se'' – "we see ourselves" ''or'' "we meet each other"

In other cases, the reflexive verb has a completely different meaning from its non-reflexive counterpart –

*''karam'' – to drive, ''karam se'' – to have a row with someone

*''gotvya'' – to cook, ''gotvya se'' – to get ready

*''smeya'' – to dare, ''smeya se'' – to laugh

;Indirect actions

When the action is performed on an indirect object, the particles change to ''si'' and its derivatives –

*''kazvam si'' – I say to myself, ''kazvash si'' – you say to yourself, ''kazvam ti'' – I say to you

*''peya si'' – I am singing to myself, ''pee si'' – she is singing to herself, ''pee mu'' – she is singing to him

*''gotvya si'' – I cook for myself, ''gotvyat si'' – they cook for themselves, ''gotvya im'' – I cook for them

In some cases, the particle ''si'' is ambiguous between the indirect object and the possessive meaning –

*''miya si ratsete'' – I wash my hands, ''miya ti ratsete'' – I wash your hands

*''pitam si priyatelite'' – I ask my friends, ''pitam ti priyatelite'' – I ask your friends

*''iskam si topkata – I want my ball (back)

The difference between transitive and intransitive verbs can lead to significant differences in meaning with minimal change, e.g. –

*''haresvash me'' – you like me, ''haresvash mi'' – I like you (lit. you are pleasing to me)

*''otivam'' – I am going, ''otivam si'' – I am going home

The particle ''si'' is often used to indicate a more personal relationship to the action, e.g. –

*''haresvam go'' – I like him, ''haresvam si go'' – no precise translation, roughly translates as "he's really close to my heart"

*''stanahme priyateli'' – we became friends, ''stanahme si priyateli'' – same meaning, but sounds friendlier

*''mislya'' – I am thinking (usually about something serious), ''mislya si'' – same meaning, but usually about something personal and/or trivial

Adverbs

The most productive way to form adverbs is to derive them from the neuter singular form of the corresponding adjective—e.g. (fast), (hard), (strange)—but adjectives ending in use the masculine singular form (i.e. ending in ), instead—e.g. (heroically), (bravely, like a man), (skillfully). The same pattern is used to form adverbs from the (adjective-like) ordinal numerals, e.g. (firstly), (secondly), (thirdly), and in some cases from (adjective-like) cardinal numerals, e.g. (twice as/double), (three times as), (five times as). The remaining adverbs are formed in ways that are no longer productive in the language. A small number are original (not derived from other words), for example: (here), (there), (inside), (outside), (very/much) etc. The rest are mostly fossilized case forms, such as: *Archaic locative forms of some adjectives, e.g. (well), (badly), (too, rather), and nouns (up), (tomorrow), (in the summer) *Archaic instrumental forms of some adjectives, e.g. (quietly), (furtively), (blindly), and nouns, e.g. (during the day), (during the night), (one next to the other), (spiritually), (in figures), (with words); or verbs: (while running), (while lying), (while standing) *Archaic accusative forms of some nouns: (today), (tonight), (in the morning), (in winter) *Archaic genitive forms of some nouns: (tonight), (last night), (yesterday) *Homonymous and etymologically identical to the feminine singular form of the corresponding adjective used with the definite article: (hard), (gropingly); the same pattern has been applied to some verbs, e.g. (while running), (while lying), (while standing) *Derived from cardinal numerals by means of a non-productive suffix: (once), (twice), (thrice) Adverbs can sometimes be reduplicated to emphasize the qualitative or quantitative properties of actions, moods or relations as performed by the subject of the sentence: "" ("rather slowly"), "" ("with great difficulty"), "" ("quite", "thoroughly").Syntax

Bulgarian employsclitic doubling

In linguistics, clitic doubling, or pronominal reduplication is a phenomenon by which clitic pronouns appear in verb phrases together with the full noun phrases that they refer to (as opposed to the cases where such pronouns and full noun phrases a ...

, mostly for emphatic purposes. For example, the following constructions are common in colloquial Bulgarian:

:

:(lit. "I gave ''it'' the present to Maria.")

:

:(lit. "I gave ''her it'' the present to Maria.")

The phenomenon is practically obligatory in the spoken language in the case of inversion signalling information structure (in writing, clitic doubling may be skipped in such instances, with a somewhat bookish effect):

:

:(lit. "The present 'to her''''it'' I-gave to Maria.")

:

:(lit. "To Maria ''to her'' 'it''I-gave the present.")

Sometimes, the doubling signals syntactic relations, thus:

:

:(lit. "Petar and Ivan ''them'' ate the wolves.")

:Transl.: "Petar and Ivan were eaten by the wolves".

This is contrasted with:

:

:(lit. "Petar and Ivan ate the wolves")

:Transl.: "Petar and Ivan ate the wolves".

In this case, clitic doubling can be a colloquial alternative of the more formal or bookish passive voice, which would be constructed as follows:

:

:(lit. "Petar and Ivan were eaten by the wolves.")

Clitic doubling is also fully obligatory, both in the spoken and in the written norm, in clauses including several special expressions that use the short accusative and dative pronouns such as "" (I feel like playing), студено ми е (I am cold), and боли ме ръката (my arm hurts):

:

:(lit. "To me ''to me'' it-feels-like-sleeping, and to Ivan ''to him'' it-feels-like-playing")

:Transl.: "I feel like sleeping, and Ivan feels like playing."

:

:(lit. "To us ''to us'' it-is cold, and to you-plur. ''to you-plur.'' it-is warm")

:Transl.: "We are cold, and you are warm."

:

:(lit. Ivan ''him'' aches the throat, and me ''me'' aches the head)

:Transl.: Ivan has sore throat, and I have a headache.

Except the above examples, clitic doubling is considered inappropriate in a formal context.

Other features

Questions

Questions in Bulgarian which do not use a question word (such as who? what? etc.) are formed with the particle ли after the verb; a subject is not necessary, as the verbal conjugation suggests who is performing the action: * – 'you are coming'; – 'are you coming?' While the particle generally goes after the verb, it can go after a noun or adjective if a contrast is needed: * – 'are you coming with us?'; * – 'are you coming with ''us''wiktionary

/ref> Rhetorical questions can be formed by adding to a question word, thus forming a "double interrogative" – * – 'Who?'; – 'I wonder who(?)' The same construction +не ('no') is an emphasized positive – * – 'Who was there?' – – 'Nearly everyone!' (lit. 'I wonder who ''wasn't'' there')

Significant verbs

=Съм

= The verb съм is pronounced similar to English ''"sum"''. – 'to be' is also used as an auxiliary for forming theperfect

Perfect commonly refers to:

* Perfection, completeness, excellence

* Perfect (grammar), a grammatical category in some languages

Perfect may also refer to:

Film

* Perfect (1985 film), ''Perfect'' (1985 film), a romantic drama

* Perfect (2018 f ...

, the passive and the conditional

Conditional (if then) may refer to:

* Causal conditional, if X then Y, where X is a cause of Y

* Conditional probability, the probability of an event A given that another event B has occurred

*Conditional proof, in logic: a proof that asserts a ...

:

*past tense – – 'I have hit'

*passive – – 'I am hit'

*past passive – – 'I was hit'

*conditional – – 'I would hit'

Two alternate forms of exist:

* – interchangeable with съм in most tenses and moods, but never in the present indicative – e.g. ('I want to be'), ('I will be here'); in the imperative, only бъда is used – ('be here');

* – slightly archaic, imperfective form of бъда – e.g. ('he used to get threats'); in contemporary usage, it is mostly used in the negative to mean "ought not", e.g. ('you shouldn't smoke').It is a common reply to the question ''Kak e?'' 'How are things?' (lit. 'how is it?') – 'alright' (lit. 'it epetitivelyis') or 'How are you?' -=Ще

= The impersonal verb (lit. 'it wants')ще – from the verb ща – 'to want.' The present tense of this verb in the sense of 'to want' is archaic and only used colloquially. Instead, искам is used. is used to for forming the (positive) future tense: * – 'I am going' * – 'I will be going' The negative future is formed with the invariable construction (see below):Formed from the impersonal verb (lit. 'it does not have') and the subjunctive particle ('that') * – 'I will not be going' The past tense of this verb – щях is conjugated to form the past conditional ('would have' – again, with да, since it is ''irrealis

In linguistics, irrealis moods (abbreviated ) are the main set of grammatical moods that indicate that a certain situation or action is not known to have happened at the moment the speaker is talking. This contrasts with the realis moods.

Every ...

''):

* – 'I would have gone;' 'you would have gone'

=Имам and нямам

= The verbs ('to have') and ('to not have'): *the third person singular of these two can be used impersonally to mean 'there is/there are' or 'there isn't/aren't any,'They can also be used on their own as a reply, with no object following: – 'there are some'; – 'there aren't any' – compare German ''keine''. e.g. ** ('there is still time' – compare Spanish ''hay''); ** ('there is no one there'). *The impersonal form няма is used in the negative future – (see ще above). ** used on its own can mean simply 'I won't' – a simple refusal to a suggestion or instruction.Conjunctions and particles

=But

= In Bulgarian, there are several conjunctions all translating into English as "but", which are all used in distinct situations. They are (), (), (), (), and () (and () – "however", identical in use to ). While there is some overlapping between their uses, in many cases they are specific. For example, is used for a choice – – "not this one, but that one" (compare Spanish ), while is often used to provide extra information or an opinion – – "I said it, but I was wrong". Meanwhile, provides contrast between two situations, and in some sentences can even be translated as "although", "while" or even "and" – – "I'm working, and he's daydreaming". Very often, different words can be used to alter the emphasis of a sentence – e.g. while and both mean "I smoke, but I shouldn't", the first sounds more like a statement of fact ("...but I mustn't"), while the second feels more like a ''judgement'' ("...but I oughtn't"). Similarly, and both mean "I don't want to, but he does", however the first emphasizes the fact that ''he'' wants to, while the second emphasizes the ''wanting'' rather than the person. is interesting in that, while it feels archaic, it is often used in poetry and frequently in children's stories, since it has quite a moral/ominous feel to it. Some common expressions use these words, and some can be used alone as interjections: * (lit. "yes, but no") – means "you're wrong to think so". * can be tagged onto a sentence to express surprise: – "he's sleeping!" * – "you don't say!", "really!"=Vocative particles

= Bulgarian has several abstract particles which are used to strengthen a statement. These have no precise translation in English.Perhaps most similar in use is the tag "man", but the Bulgarian particles are more abstract still. The particles are strictly informal and can even be considered rude by some people and in some situations. They are mostly used at the end of questions or instructions. * () – the most common particle. It can be used to strengthen a statement or, sometimes, to indicate derision of an opinion, aided by the tone of voice. (Originally purely masculine, it can now be used towards both men and women.) ** – tell me (insistence); – is that so? (derisive); – you don't say!. * ( – expresses urgency, sometimes pleading. ** – come on, get up! * () (feminine only) – originally simply the feminine counterpart of , but today perceived as rude and derisive (compare the similar evolution of the vocative forms of feminine names). * (, masculine), (, feminine) – similar to and , but archaic. Although informal, can sometimes be heard being used by older people.=Modal particles

= These are "tagged" on to the beginning or end of a sentence to express the mood of the speaker in relation to the situation. They are mostlyinterrogative

An interrogative clause is a clause whose form is typically associated with question-like meanings. For instance, the English sentence "Is Hannah sick?" has interrogative syntax which distinguishes it from its declarative counterpart "Hannah is ...

or slightly imperative in nature. There is no change in the grammatical mood when these are used (although they may be expressed through different grammatical moods in other languages).

* () – is a universal affirmative tag, like "isn't it"/"won't you", etc. (it is invariable, like the French ). It can be placed almost anywhere in the sentence, and does not always require a verb:

** – you are coming, aren't you?; – didn't they want to?; – that one, right?;

**it can express quite complex thoughts through simple constructions – – "I thought you weren't going to!" or "I thought there weren't any!" (depending on context – the verb presents general negation/lacking, see "nyama", above).

* () – expresses uncertainty (if in the middle of a clause, can be translated as "whether") – e.g. – "do you think he will come?"

* () – presents disbelief ~"don't tell me that..." – e.g. – "don't tell me you want to!". It is slightly archaic, but still in use. Can be used on its own as an interjection –

* () – expresses hope – – "he will come"; – "I hope he comes" (compare Spanish ). Grammatically, is entirely separate from the verb – "to hope".

* () – means "let('s)" – e.g. – "let him come"; when used in the first person, it expresses extreme politeness: – "let us go" (in colloquial situations, , below, is used instead).

**, as an interjection, can also be used to express judgement or even schadenfreude

Schadenfreude (; ; 'harm-joy') is the experience of pleasure, joy, or self-satisfaction that comes from learning of or witnessing the troubles, failures, or humiliation of another. It is a borrowed word from German, with no direct translation ...

– – "he deserves it!".

=Intentional particles

= These express intent or desire, perhaps even pleading. They can be seen as a sort of cohortative side to the language. (Since they can be used by themselves, they could even be considered as verbs in their own right.) They are also highly informal. * () – "come on", "let's" **e.g. – "faster!" * () – "let me" – exclusively when asking someone else for something. It can even be used on its own as a request or instruction (depending on the tone used), indicating that the speaker wants to partake in or try whatever the listener is doing. ** – let me see; or – "let me.../give me..." * () (plural ) – can be used to issue a negative instruction – e.g. – "don't come" ( + subjunctive). In some dialects, the construction ( +preterite

The preterite or preterit (; abbreviated or ) is a grammatical tense or verb form serving to denote events that took place or were completed in the past; in some languages, such as Spanish, French, and English, it is equivalent to the simple pas ...

) is used instead. As an interjection – – "don't!" (See section on imperative mood).

These particles can be combined with the vocative particles for greater effect, e.g. (let me see), or even exclusively in combinations with them, with no other elements, e.g. (come on!); (I told you not to!).

Pronouns of quality

Bulgarian has several pronouns of quality which have no direct parallels in English – ''kakav'' (what sort of); ''takuv'' (this sort of); ''onakuv'' (that sort of – colloq.); ''nyakakav'' (some sort of); ''nikakav'' (no sort of); ''vsyakakav'' (every sort of); and the relative pronoun ''kakavto'' (the sort of ... that ... ). The adjective ''ednakuv'' ("the same") derives from the same radical.Like thedemonstratives

Demonstratives (list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) are words, such as ''this'' and ''that'', used to indicate which entities are being referred to and to distinguish those entities from others. They are typically deictic; their meaning ...

, these take the same form as pronouns as they do as adjectives – ie. ''takuv'' means both "this kind of..." (adj.) and ''this kind of person/thing'' (pron., depending on the context).

Example phrases include:

*''kakav chovek?!'' – "what person?!"; ''kakav chovek e toy?'' – what sort of person is he?

*''ne poznavam takuv'' – "I don't know any (people like that)" (lit. "I don't know this sort of (person)")

*''nyakakvi hora'' – lit. "some type of people", but the understood meaning is "a bunch of people I don't know"

*''vsyakakvi hora'' – "all sorts of people"

*''kakav iskash?'' – "which type do you want?"; ''nikakav!'' – "I don't want any!"/"none!"

An interesting phenomenon is that these can be strung along one after another in quite long constructions, e.g.

An extreme (colloquial) sentence, with almost no ''physical'' meaning in it whatsoever – yet which ''does'' have perfect meaning to the Bulgarian ear – would be :

*"kakva e taya takava edna nyakakva nikakva?!"

*inferred translation – "what kind of no-good person is she?"

*literal translation: "what kind of – is – this one here (she) – this sort of – one – some sort of – no sort of"

—Note: the subject of the sentence is simply the pronoun "taya" (lit. "this one here"; colloq. "she").

Another interesting phenomenon that is observed in colloquial speech is the use of ''takova'' (neuter of ''takyv'') not only as a substitute for an adjective, but also as a substitute for a verb. In that case the base form ''takova'' is used as the third person singular in the present indicative and all other forms are formed by analogy to other verbs in the language. Sometimes the "verb" may even acquire a derivational prefix that changes its meaning. Examples:

* ''takovah ti shapkata'' – I did something to your hat (perhaps: I took your hat)

* ''takovah si ochilata'' – I did something to my glasses (perhaps: I lost my glasses)

* ''takovah se'' – I did something to myself (perhaps: I hurt myself)

Another use of ''takova'' in colloquial speech is the word ''takovata'', which can be used as a substitution for a noun, but also, if the speaker doesn't remember or is not sure how to say something, they might say ''takovata'' and then pause to think about it:

* ''i posle toy takovata...'' – and then he o translation

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), plu ...

...

* ''izyadoh ti takovata'' – I ate something of yours (perhaps: I ate your dessert). Here the word ''takovata'' is used as a substitution for a noun.

As a result of this versatility, the word ''takova'' can be used as a euphemism for ''literally anything.'' It is commonly used to substitute words relating to reproductive organs or sexual acts, for example:

* ''toy si takova takovata v takovata i'' - he erbhis oun Oun or OUN may refer to

People

* Ahmed Oun (born '1946), Libyan major general

* Ek Yi Oun (1910–2013), Cambodian politician

* Kham-Oun I (1885–1915), Lao queen consort

* Õun, an Estonian surname; notable people with this surname

* Oun Kham (18 ...

in her oun Oun or OUN may refer to

People

* Ahmed Oun (born '1946), Libyan major general

* Ek Yi Oun (1910–2013), Cambodian politician

* Kham-Oun I (1885–1915), Lao queen consort

* Õun, an Estonian surname; notable people with this surname

* Oun Kham (18 ...

Similar "meaningless" expressions are extremely common in spoken Bulgarian, especially when the speaker is finding it difficult to describe something.

Miscellaneous

*The commonly cited phenomenon of Bulgarian people shaking their head for "yes" and nodding for "no" is true but, with the influence of Western culture, ever rarer, and almost non-existent among the younger generation. (The shaking and nodding are ''not'' identical to the Western gestures. The "nod" for ''no'' is actually an ''upward'' movement of the head rather than a downward one, while the shaking of the head for ''yes'' is not completely horizontal, but also has a slight "wavy" aspect to it.) **A dental click (similar to the English "tsk") also means "no" (informal), as does ''ъ-ъ'' (the only occurrence in Bulgarian of theglottal stop

The glottal plosive or stop is a type of consonantal sound used in many spoken languages, produced by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract or, more precisely, the glottis. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents thi ...

). The two are often said with the upward 'nod'.

*Bulgarian has an extensive vocabulary covering family relationships

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

. The biggest range of words is for uncles and aunts, e.g. ''chicho'' (your father's brother), ''vuicho'' (your mother's brother), svako (your aunt's husband); an even larger number of synonyms for these three exists in the various dialects of Bulgarian, including ''kaleko, lelincho, tetin'', etc. The words do not only refer to the closest members of the family (such as ''brat'' – brother, but ''batko''/''bate'' – older brother, ''sestra'' – sister, but ''kaka'' – older sister), but extend to its furthest reaches, e.g. ''badzhanak'' from Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...