Brunot Treaty Of 1873 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ouray (, 1833 – August 24, 1880) was a Native American

Ouray (, 1833 – August 24, 1880) was a Native American

Ouray was born in 1833 near the

Ouray was born in 1833 near the

Ouray negotiated with the U.S. government for the Treaty of Conejos (1863), which reduced their lands to 50% of what it had been, losing all lands east of the

Ouray negotiated with the U.S. government for the Treaty of Conejos (1863), which reduced their lands to 50% of what it had been, losing all lands east of the

Around 1866, there were some Native Americans who had stolen livestock and otherwise upset new settlers. Following an uprising by Chief Kaniatse, Colonel

Around 1866, there were some Native Americans who had stolen livestock and otherwise upset new settlers. Following an uprising by Chief Kaniatse, Colonel

The U.S. government appointed a commission to determine a reservation for the Ute and Ouray and Chipeta went to Washington, D.C. in 1880 for the final treaty for the Utes. Members of the commission were

The U.S. government appointed a commission to determine a reservation for the Ute and Ouray and Chipeta went to Washington, D.C. in 1880 for the final treaty for the Utes. Members of the commission were

Ouray's first wife, Black Mare, died after the birth of their only child, a boy named Queashegut, also known as Pahlone, and called ''Paron'' (apple) by his father because of his round, dimpled face. In 1859, Ouray married the sixteen-year old

Ouray's first wife, Black Mare, died after the birth of their only child, a boy named Queashegut, also known as Pahlone, and called ''Paron'' (apple) by his father because of his round, dimpled face. In 1859, Ouray married the sixteen-year old

Chipeta: Glory and Heartache"

''The Outlaw Trail Journal'', n.d., Salt Lake City, Utah, on Utah State University, Unintah Basin Education Center Website * See "Danger of Bloody Collisions", "Chief Ouray, the Statesman", and "The Gift to the Great Father" *Smith, P. David. ''Ouray Chief of the Utes'' Wayfinder Press: Ouray, Colorado, 1990. *Wyss, Thelma Hatch. ''Bear Dancer the Story of a Ute Girl'' Margaret K. McElderry Books: New York, 2010.

"Chief Ouray"

Southern Ute

''History to Go'', Utah State Website

"Ouray´s son... or not?"

American-Tribes.com

"Old Photos - Ute"

American-Tribes.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Ouray 1833 births 1880 deaths 19th-century Native Americans Native American leaders People from Taos, New Mexico Ute people

Ouray (, 1833 – August 24, 1880) was a Native American

Ouray (, 1833 – August 24, 1880) was a Native American chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

of the Tabeguache

The Uncompahgre Ute () or ꞌAkaꞌ-páa-gharʉrʉ Núuchi (also: Ahkawa Pahgaha Nooch) is a band of the Ute, a Native American tribe located in the US states of Colorado and Utah. In the Ute language, means "rocks that make water red." The band ...

(Uncompahgre) band of the Ute tribe

Ute () are the Indigenous people of the Ute tribe and culture among the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. They had lived in sovereignty in the regions of present-day Utah and Colorado in the Southwestern United States for many centuries unt ...

, then located in western Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

. Because of his leadership ability, Ouray was acknowledged by the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

as a chief of the Ute and he traveled to Washington, D.C. to negotiate for the welfare of the Utes. Raised in the culturally diverse town of Taos

Taos or TAOS may refer to:

Places

* Taos, Missouri, a city in Cole County, Missouri, United States

* Taos County, New Mexico, United States

** Taos, New Mexico, a city, the county seat of Taos County, New Mexico

*** Taos art colony, an art colo ...

, Ouray learned to speak many languages that helped him in the negotiations, which were complicated by the manipulation of his grief over his five-year-old son abducted during attack by the Sioux and trantee. Ouray met with Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and Hayes and was called the man of peace because he sought to make treaties with settlers and the government.

Following the Meeker Massacre

Meeker Massacre, or Meeker Incident, White River War, Ute War, or the Ute Campaign), took place on September 29, 1879 in Colorado. Members of a band of Ute Indians ( Native Americans) attacked the Indian agency on their reservation, killing th ...

(White River War) of 1879, he traveled in 1880 to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

He tried to secure a treaty for the Uncompahgre Ute

The Uncompahgre Ute () or ꞌAkaꞌ-páa-gharʉrʉ Núuchi (also: Ahkawa Pahgaha Nooch) is a band of the Ute, a Native American tribe located in the US states of Colorado and Utah. In the Ute language, means "rocks that make water red." The band ...

, who wanted to stay in Colorado; but, the following year, the United States forced the Uncompahgre and the White River Ute to the west to reservations in present-day Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

.

Early life and education

Ouray was born in 1833 near the

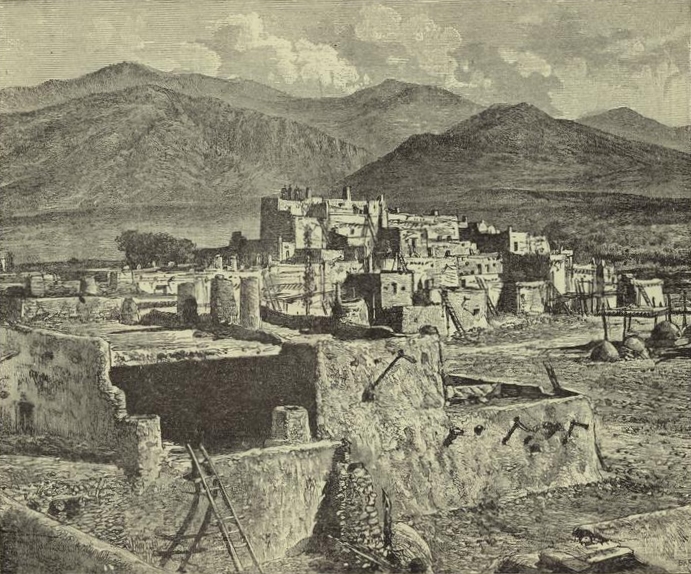

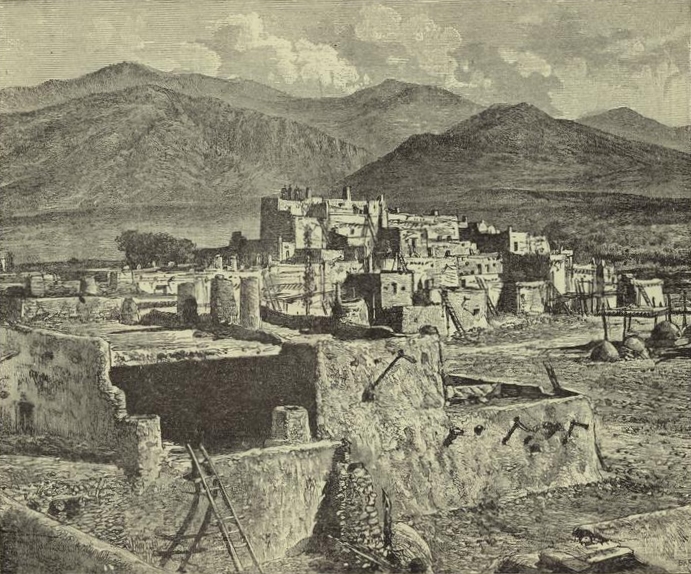

Ouray was born in 1833 near the Taos Pueblo

Taos Pueblo (or Pueblo de Taos) is an ancient pueblo belonging to a Taos-speaking (Tiwa) Native American tribe of Puebloan people. It lies about north of the modern city of Taos, New Mexico. The pueblos are considered to be one of the oldest c ...

in Nuevo México, now in the state of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

. His father, Guera Murah, also called Salvador, was a Jicarilla Apache

Jicarilla Apache (, Jicarilla language: Jicarilla Dindéi), one of several loosely organized autonomous bands of the Eastern Apache, refers to the members of the Jicarilla Apache Nation currently living in New Mexico and speaking a Southern Athab ...

adopted into the Ute, and his mother was Uncompahgre Ute.

His parents had another son named Quench, and then his mother died soon after. His father remarried and his stepmother left Ouray and his brother to live on a ranch with a Spanish-speaking couple around 1843 or 1845. His father returned to Colorado and became a leader of the ''Tabeguache

The Uncompahgre Ute () or ꞌAkaꞌ-páa-gharʉrʉ Núuchi (also: Ahkawa Pahgaha Nooch) is a band of the Ute, a Native American tribe located in the US states of Colorado and Utah. In the Ute language, means "rocks that make water red." The band ...

'' Ute band and the boys remained in Taos. Ouray received a Catholic education and was raised in the Catholic faith. Living in a culturally diverse location, he learned Ute and Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño an ...

languages, sign language, Spanish, and English, which he found helpful later in life in negotiating with whites and Native Americans. He spent much of his youth working for Mexican sheepherders. He also hauled wood and packed mules that were bound for the Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, th ...

.

In 1850, Ouray and his brother left Taos to join their father, who died soon after. Ouray was the band's best rider, hunter, and fighter, and he became an enforcer (like a chief of police) and then sub-chief of the band. He fought both the Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and eve ...

and the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

while living among the Tabeguache.

Chief and negotiator

Chief

In 1860, Ouray became chief of the band at the age of 27. That year, he engaged in a "fact-finding tour" to determine the number of whites that were settling in the Uncompahgre and Gunnison River valleys and was alarmed by the number of miners and settlers on ancestral lands of the Utes. He understood, though, that fighting the whites would not turn back the tide of immigrants. Instead, he believed that the solution was to engage in treaty negotiations to protect their interests.Treaty negotiation

Ouray was known as the "White man's friend," and his services were almost indispensable to the government in negotiating with his tribe, who kept in good faith all treaties that were made by him. He protected their interests as far as possible, and set them the example of living a civilized life. Although Ouray sought reconciliation between different peoples, with the belief that war with the whites likely meant the demise of the Ute tribe, other more militant Utes considered him a coward for his propensity to negotiate. Disturbed by the treaties that Ouray entered into, his brother-in-law "Hot Stuff" tried to kill him with an axe during his near-daily visit to theLos Piños Indian Agency

LOS, or Los, or LoS may refer to:

Science and technology

* Length of stay, the duration of a single episode of hospitalisation

* Level of service, a measure used by traffic engineers

* Level of significance, a measure of statistical significan ...

in 1874.

Treaty of Conejos of 1863

Colorado Territory was established on February 28, 1861. In 1862, he convinced Utes to negotiate with the government to enter into a treaty to ensure the protection of hereditary lands of the Tabeguache.Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and n ...

had noticed in 1862 that prospectors were mining and settling in areas that had been traditional hunting grounds for the Utes and game was becoming scarce. Carson helped him draft a treaty. Ouray was part of the delegation and was the translator in a meeting with the new Territorial Governor John Evans, after which he traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

Ouray negotiated with the U.S. government for the Treaty of Conejos (1863), which reduced their lands to 50% of what it had been, losing all lands east of the

Ouray negotiated with the U.S. government for the Treaty of Conejos (1863), which reduced their lands to 50% of what it had been, losing all lands east of the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

that included healing waters at Manitou Springs

Manitou Springs is a home rule municipality located at the foot of Pikes Peak in western El Paso County, Colorado, United States. The town was founded for its natural mineral springs. The downtown area continues to be of interest to travelers ...

and the sacred land on Pikes Peak

Pikes Peak is the List of mountain ranges of Colorado#Mountain ranges, highest summit of the southern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, in North America. The Ultra-prominent peak, ultra-prominent fourteener is located in Pike National Forest ...

. It guaranteed that they would have the western one third of the state of the Colorado. The Utes agreed that they would allow roads and military forts to be built on the land. As an encouragement to take up farming, they were given sheep, cattle, and $10,000 in goods and provisions over ten years. The government generally did not provide the goods, provisions, or livestock mentioned in the treaty, and since game was scarce many Ute continued to hunt on ancestral Ute lands until they were removed to reservations in 1880 and 1881.

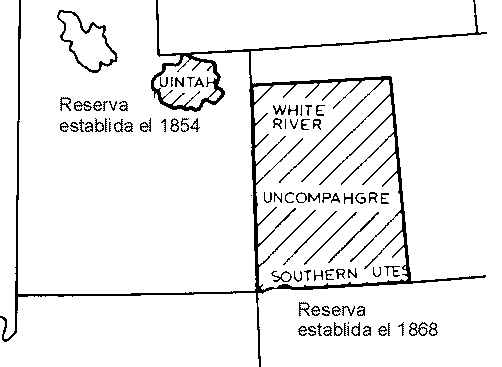

Treaty of 1868

Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and n ...

successfully negotiated a treaty with the Ouray and other Ute leaders in 1867. In the meantime, the government became interested in obtaining some more Ute land. Since the government had not lived up to its agreement to provide provisions for the winter months, Ouray was reluctant to give the government more land. Many Native Americans, though, were "in dire straits" and he agreed to be part of a delegation.

In 1868, Ouray, Nicaagat

Nicaagat (leaves becoming green, 1840–1882), also known as Chief, Captain and Ute Jack and Green Leaf. A Ute warrior and subchief, he led a Ute war party against the United States Army when it crossed Milk Creek onto the Ute reservation, which ...

, with Kit Carson were among a delegation to negotiate a treaty that would result in the creation of a reservation for the Ute, served by an Indian Agencies at White River and near Montrose with a school, blacksmith shop, sawmill, and warehouse. They lost a little land in the treaty, but Ouray hoped that having a government presence would mean that their lands would be protected. The treaty was signed by 47 Ute chiefs.

Brunot Treaty of 1873

Silver deposits were found in theSan Juan Mountains

The San Juan Mountains is a high and rugged mountain range in the Rocky Mountains in southwestern Colorado and northwestern New Mexico. The area is highly mineralized (the Colorado Mineral Belt) and figured in the gold and silver mining industry ...

in 1872 and the government wanted again to negotiate for more land. Feeding on his grief due to the unknown status of his son after the Utes were attacked by the Sioux, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Felix Brunot had a 17-year-old orphan brought by Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

Chief Powder Face to meet Ouray and Chipeta in Washington, D.C. ten years after the abduction. This was the first of many attempts by Brunot to find his son and was conducted so that Ouray would relinquish mining property and keep treaty talks open. The boy was clearly not Ouray's son, he did not know anything from the Ute language, did not want to go with Ouray, and the details of his capture did not match the experience of Ouray's son. Tribal historians have stated that this meeting was upsetting to Ouray, but author Richard E. Wood states that the chief was impressed by the effort taken by the government. In 1873, with Ouray's help, the Brunot Agreement was ratified and the United States acquired the mineral-rich property they had been seeking. In exchange, the Native Americans were to receive provisions over time. Ouray was given land and a house in the Uncompahgre Valley near the Indian Agency. The government, though, was again reluctant to provide provisions. His negotiations had included a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

.

Meeker Massacre

Tensions increased in the area following theMeeker Massacre

Meeker Massacre, or Meeker Incident, White River War, Ute War, or the Ute Campaign), took place on September 29, 1879 in Colorado. Members of a band of Ute Indians ( Native Americans) attacked the Indian agency on their reservation, killing th ...

(1879) at the White River Indian Agency. Not understanding the Utes' love of horses, Nathan Meeker

Nathan Cook Meeker (July 12, 1817 – September 30, 1879) was a 19th-century American journalist, homesteader, entrepreneur, and Indian agent for the federal government. He is noted for his founding in 1870 of the Union Colony, a cooperative ...

had their race track plowed and tried to force the nomadic hunters and gatherers to farm, and Meeker sought military help. Seeking peace, a tribe of Ute men led by Chief Douglas asked Meeker for peace, but a fight ensued. This made further negotiations for peace between Native Americans and whites very difficult. Local settlers demanded that the Utes be moved. When Ouray found out about the massacre, he asked, as head of the Utes, for the warriors to disperse and release hostages to him. The hostages, including Josephine Meeker

Josephine Meeker (January 28, 1857 – December 20, 1882), was a teacher and physician at the White River Indian Agency in Colorado Territory, where her father Nathan Meeker was the United States (US) agent. On September 29, 1879, he and 10 o ...

, were delivered to Ouray's house at the Los Piños Indian Agency and were cared for by Chipeta.

Final treaty

The U.S. government appointed a commission to determine a reservation for the Ute and Ouray and Chipeta went to Washington, D.C. in 1880 for the final treaty for the Utes. Members of the commission were

The U.S. government appointed a commission to determine a reservation for the Ute and Ouray and Chipeta went to Washington, D.C. in 1880 for the final treaty for the Utes. Members of the commission were Alfred B. Meacham

Alfred Benjamin Meacham (1826–1882) was an American Methodist minister, reformer, author and historian, who served as the U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon (1869–1872). He became a proponent of American Indian interests in the ...

, former U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon; Otto Mears

Otto Mears (May 3, 1840 – June 24, 1931) was a famous Colorado railroad builder and entrepreneur who played a major role in the early development of southwestern Colorado.

Mears was known as the "Pathfinder of the San Juans" because of hi ...

, a railroad executive, and George W. Manypenny, former Commissioner of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal government of the United States, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

. When President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

met Ouray in Washington, DC, he said that the Ute was "the most intellectual man I've ever conversed with."

When he had returned to Colorado, and while dying with Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied b ...

, Ouray traveled to the Ignacio Indian Agency office to have the treaty signed by the Southern Utes.

Utes were later put on a reservation in Utah, Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation

The Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation (, ) is located in northeastern Utah, United States. It is the homeland of the Ute Indian Tribe (Ute dialect: Núuchi-u), and is the largest of three Indian reservations inhabited by members of the Ute Tribe ...

, as well as two reservations in Colorado: Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (Ute dialect: Wʉgama Núuchi) is one of three federally recognized tribes of the Ute Nation, and are mostly descendants of the historic Weeminuche Band who moved to the Southern Ute reservation in 1897. Their reservati ...

and Southern Ute Indian Reservation

The Southern Ute Indian Reservation (Ute dialect: Kapuuta-wa Moghwachi Núuchi-u) is a Native American reservation in southwestern Colorado near the northern New Mexico state line. Its territory consists of land from three counties; in descendin ...

.

Personal life

Ouray's first wife, Black Mare, died after the birth of their only child, a boy named Queashegut, also known as Pahlone, and called ''Paron'' (apple) by his father because of his round, dimpled face. In 1859, Ouray married the sixteen-year old

Ouray's first wife, Black Mare, died after the birth of their only child, a boy named Queashegut, also known as Pahlone, and called ''Paron'' (apple) by his father because of his round, dimpled face. In 1859, Ouray married the sixteen-year old Chipeta

Chipeta or White Singing Bird (1843 or 1844 – August 1924) was a Native American woman, and the second wife of Chief Ouray of the Uncompahgre Ute tribe. Born a Kiowa Apache, she was raised by the Utes in what is now Conejos, Colorado. An adv ...

( Ute meaning: White Singing Bird), who had been caring for Ouray's son since Black Mare's death earlier that year.

When Queashegut was five years old, Ouray took him along on a buffalo hunt with a total party of 31 men in 1860 or 1863. Their hunting camp, near Fort Lupton, was attacked by 300 Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

warriors and Queashegut left the tepee where he sought shelter with Chipeta to follow Ute warriors. After the fight, they were unable to find him. He had been captured and traded to an Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

band. Ouray never saw his son again and remained in deep grief. He tried to find his son for the rest of his life and feared "he was raised to fight against his own." While visiting Kit Carson at Fort Garland

Fort Garland (1858–1883), Colorado, United States, was designed to house two companies of soldiers to protect settlers in the San Luis Valley, then in the Territory of New Mexico. It was named for General John Garland, commander of the Military ...

in 1866, Ouray and Chipeta met and adopted two girls and two boys.

Ouray's sister, Shawsheen (also Tsashin and Susan), was in Big Thompson Canyon

The Big Thompson River is a tributary of the South Platte River, approximately 78 miles (123 km) long, in the U.S. state of Colorado. Originating in Forest Canyon in Rocky Mountain National Park, the river flows into Lake Estes in the town ...

in 1861 or 1863 when she was abducted by the Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

. Soldiers from Fort Collins

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

found her two years later in 1863 or 1865, but she was afraid of them and escaped. She was later found by Utes and returned to Ouray's tribe.

He had several homes in Colorado, one of them by the town of Ouray. For twenty years, Ouray lived with Chipeta on a farm on the Uncompahgre River

The Uncompahgre River is a tributary of the Gunnison River, approximately 75 mi (121 km) long, in southwestern Colorado in the United States. Lake Como at 12,215 ft (3723m) in northern San Juan County, in the Uncompahgre National ...

near Montrose. The 300-acre farm had pasture land and 50 acres of irrigated farm land. The six-room adobe house was well-furnished, including a piano and fine china. The Ute Indian Museum

The Ute Indian Museum is a local history museum in Montrose, Colorado, Montrose, Colorado, United States. It is administered by History Colorado (the Colorado Historical Society).

The museum presents the history of the Ute tribe of Native America ...

is located on their original 8.65 acre homestead in Montrose. Chipeta was a member of a Methodist church; Ouray was an Episcopalian. Ouray never cut his long Ute-fashion hair, though he often dressed in the European-American style.

Ouray died on August 24, 1880, near the Los Piños Indian Agency in Colorado. His people secretly buried him near Ignacio, Colorado

The Town of Ignacio (Ute language: Piinuu) is a Statutory Town in La Plata County, Colorado, United States. The population was 697 at the 2010 United States Census. It is the headquarters of the Southern Ute Indian Reservation.

Geography

Ignac ...

. Forty-five years later, in 1925, his bones were re-interred in a full ceremony led by Buckskin Charley and John McCook at the Ignacio cemetery.

A 1928 article in the ''Denver Post'' reads in part, "He saw the shadow of doom on his people" and a 2012 article writes, "He sought peace among tribes and whites, and a fair shake for his people, though Ouray was dealt a sad task of liquidating a once-mighty force that ruled nearly 23 million acres of the Rocky Mountains."

Legacy and honors

Ouray's obituary in ''The Denver Tribune'' stated:In the death of Ouray, one of the historical characters passes away. He has figured for many years as the greatest Indian of his time, and during his life has figured quite prominently. Ouray is in many respects...a remarkable Indian...pure instincts and keen perception. A friend to the white man and protector to the Indians alike.

Places named for Ouray

*Camp Chief Ouray

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

, located in Granby, Colorado.

*Mount Ouray

Mount Ouray is a high and prominent mountain summit in the far southern Sawatch Range of the Rocky Mountains of North America. The thirteener is located in San Isabel National Forest, west ( bearing 270°) of Poncha Pass, Colorado, United ...

in the Sawatch Mountain Range and Ouray Peak

Ouray Peak, elevation , is a summit in the Sawatch Mountains of Colorado. The peak is south of Independence Pass in the Collegiate Peaks Wilderness of San Isabel National Forest.

See also

* List of Colorado mountain ranges

* List of Colora ...

in Chaffee County, both in Colorado, were named for him.

*Ouray County

Ouray County is a county located in the U.S. state of Colorado. As of the 2020 census, the population was 4,874. The county seat is Ouray. Because of its rugged mountain topography, Ouray County is also known as the Switzerland of America.

H ...

and its county seat, the town of Ouray in Colorado, as well as the community of Ouray, Utah

Ouray is an unincorporated village of the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation, located in west‑central Uintah County, Utah, United States.

Description

The community is located primarily on the north bank of the confluence of the Duchesne and ...

are named for him.

* SS ''Chief Ouray'', a World War II liberty ship, now named USS ''Deimos''

Notes

References

Further reading

*Bueler, Gladys R. ''Colorado's Colorful Characters'' Pruett Publishing Company: Boulder, Colorado, 1981. *Grant, Bruce. ''The Concise Encyclopedia of the American Indian'' 3rd ed., Wings Books: New York, 2000. *Jenson, H. BertChipeta: Glory and Heartache"

''The Outlaw Trail Journal'', n.d., Salt Lake City, Utah, on Utah State University, Unintah Basin Education Center Website * See "Danger of Bloody Collisions", "Chief Ouray, the Statesman", and "The Gift to the Great Father" *Smith, P. David. ''Ouray Chief of the Utes'' Wayfinder Press: Ouray, Colorado, 1990. *Wyss, Thelma Hatch. ''Bear Dancer the Story of a Ute Girl'' Margaret K. McElderry Books: New York, 2010.

External links

*"Chief Ouray"

Southern Ute

''History to Go'', Utah State Website

"Ouray´s son... or not?"

American-Tribes.com

"Old Photos - Ute"

American-Tribes.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Ouray 1833 births 1880 deaths 19th-century Native Americans Native American leaders People from Taos, New Mexico Ute people