Brunel Gauge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Brunel worked for several years as an assistant engineer on the project to create a tunnel under London's

Brunel worked for several years as an assistant engineer on the project to create a tunnel under London's

Brunel is perhaps best remembered for designs for the

Brunel is perhaps best remembered for designs for the  Work on the Clifton bridge started in 1831, but was suspended due to the Queen Square riots caused by the arrival of Sir

Work on the Clifton bridge started in 1831, but was suspended due to the Queen Square riots caused by the arrival of Sir  Throughout his railway building career, but particularly on the

Throughout his railway building career, but particularly on the

In the early part of Brunel's life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for goods. This influenced Brunel's involvement in railway engineering, including railway bridge engineering.

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the

In the early part of Brunel's life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for goods. This influenced Brunel's involvement in railway engineering, including railway bridge engineering.

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the  Drawing on Brunel's experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements—soaring

Drawing on Brunel's experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements—soaring

Though unsuccessful, another of Brunel's interesting use of technical innovations was the

Though unsuccessful, another of Brunel's interesting use of technical innovations was the

Brunel had proposed extending its transport network by boat from Bristol across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City before the Great Western Railway opened in 1835. The

Brunel had proposed extending its transport network by boat from Bristol across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City before the Great Western Railway opened in 1835. The  When it was built, the ''Great Western'' was the longest ship in the world at with a

When it was built, the ''Great Western'' was the longest ship in the world at with a

While performing a conjuring trick for the amusement of his children in 1843 Brunel accidentally inhaled a

While performing a conjuring trick for the amusement of his children in 1843 Brunel accidentally inhaled a

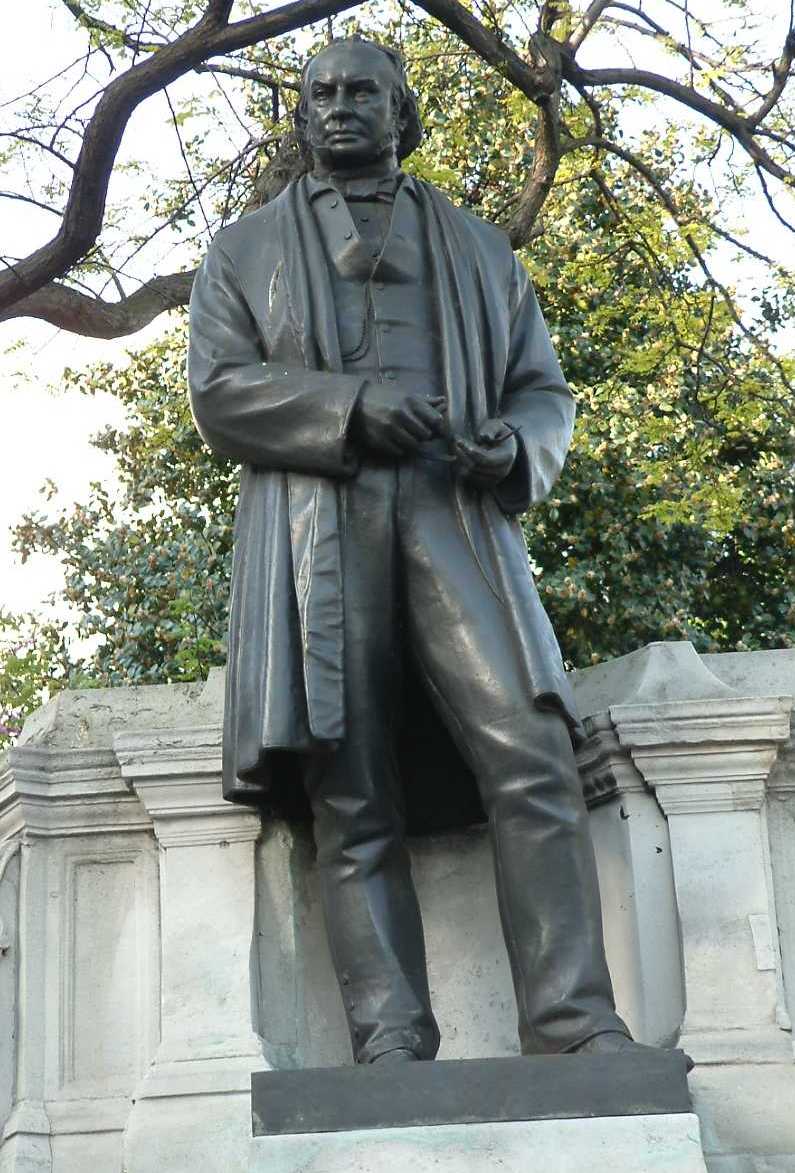

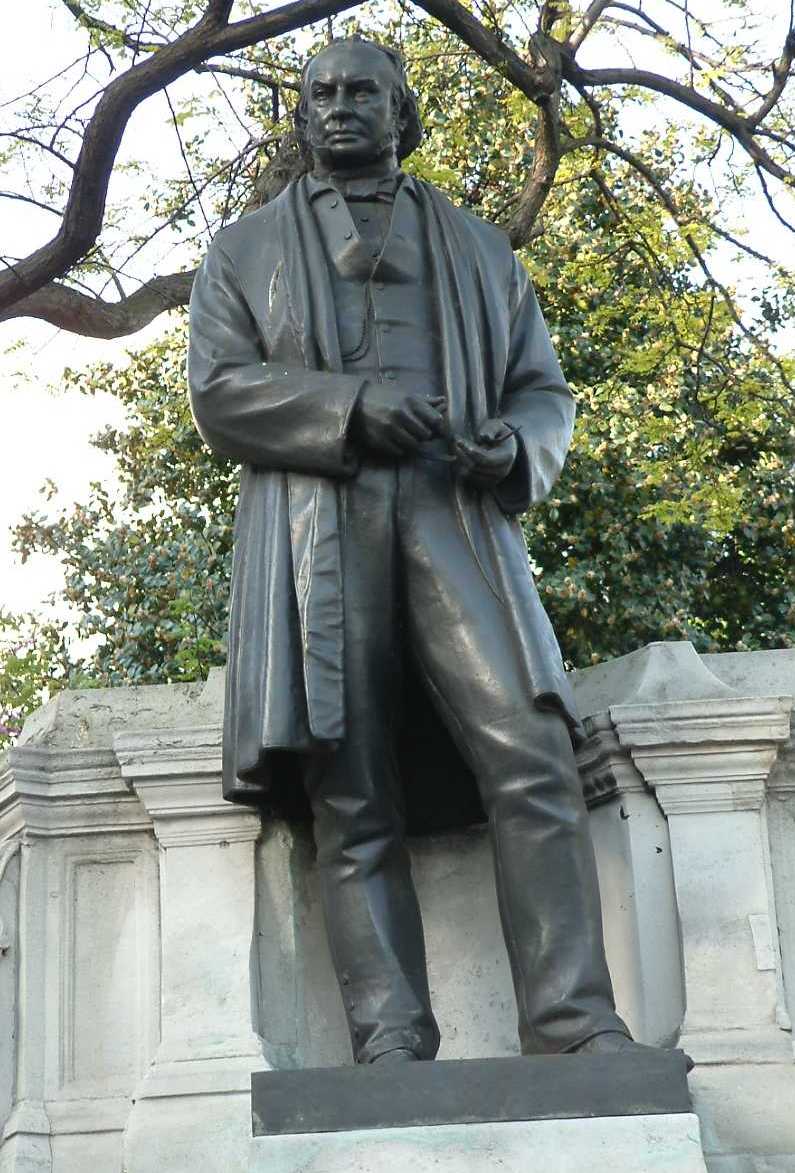

A celebrated engineer in his era, Brunel remains revered today, as evidenced by numerous monuments to him. There are statues in London at

A celebrated engineer in his era, Brunel remains revered today, as evidenced by numerous monuments to him. There are statues in London at

in 2001 to select the

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British

public poll to determine the "civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one of the greatest figures of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, hochanged the face of the English landscape with his groundbreaking designs and ingenious constructions." Brunel built dockyards, the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

(GWR), a series of steamships including the first propeller-driven transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film), ...

steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

, and numerous important bridges and tunnels. His designs revolutionised public transport and modern engineering.

Though Brunel's projects were not always successful, they often contained innovative solutions to long-standing engineering problems. During his career, Brunel achieved many engineering firsts, including assisting in the building of the first tunnel under a navigable river

A body of water, such as a river, canal or lake, is navigable if it is deep, wide and calm enough for a water vessel (e.g. boats) to pass safely. Such a navigable water is called a ''waterway'', and is preferably with few obstructions against dir ...

(the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

) and the development of the , the first propeller-driven, ocean-going iron ship, which, when launched in 1843, was the largest ship ever built.

On the GWR, Brunel set standards for a well-built railway, using careful surveys to minimise gradients and curves. This necessitated expensive construction techniques, new bridges, new viaducts, and the Box Tunnel

Box Tunnel passes through Box Hill on the Great Western Main Line (GWML) between Bath and Chippenham. The tunnel was the world's longest railway tunnel when it was completed in 1841.

Built between December 1838 and June 1841 for the Great W ...

. One controversial feature was the "broad gauge

A broad-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge (the distance between the rails) broader than the used by standard-gauge railways.

Broad gauge of , commonly known as Russian gauge, is the dominant track gauge in former Soviet Union (CIS ...

" of , instead of what was later to be known as "standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), International gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge and European gauge in Europe, and SGR in Ea ...

" of . He astonished Britain by proposing to extend the GWR westward to North America by building steam-powered, iron-hulled ships. He designed and built three ships that revolutionised naval engineering: the (1838), the (1843), and the (1859).

In 2002, Brunel was placed second in a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...100 Greatest Britons

''100 Greatest Britons'' is a television series that was broadcast by the BBC in 2002. It was based on a television poll conducted to determine who the British people at that time considered the greatest Britons in history. The series included in ...

." In 2006, the bicentenary of his birth, a major programme of events celebrated his life and work under the name ''Brunel 200''.

Early life

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born on 9 April 1806 in Britain Street, Portsea,Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, where his father was working on block-making machinery. He was named Isambard after his father, the French civil engineer Sir Marc Isambard Brunel

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (, ; 25 April 1769 – 12 December 1849) was a French-British engineer who is most famous for the work he did in Britain. He constructed the Thames Tunnel and was the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Born in Franc ...

, and Kingdom after his English mother, Sophia Kingdom

Sophia Kingdom (15 February 1775 – 5 January 1855), later known as Lady Brunel, was the mother of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Her father was William Kingdom, a contracting agent for the Royal Navy and the army, and her mother was Joan Spry. She wa ...

.

He had two elder sisters, Sophia, the eldest child, and Emma. The whole family moved to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1808 for his father's work. Brunel had a happy childhood, despite the family's constant money worries, with his father acting as his teacher during his early years. His father taught him drawing and observational techniques from the age of four, and Brunel had learned Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematics, Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry: the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements''. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small ...

by eight. During this time, he also learned to speak French fluently and the basic principles of engineering. He was encouraged to draw interesting buildings and identify any faults in their structure.Buchanan (2006), p. 18

When Brunel was eight, he was sent to Dr Morrell's boarding school in Hove

Hove is a seaside resort and one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove, along with Brighton in East Sussex, England. Originally a "small but ancient fishing village" surrounded by open farmland, it grew rapidly in the 19th cen ...

, where he learned classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

. His father, a Frenchman by birth, was determined that Brunel should have access to the high-quality education he had enjoyed in his youth in France; accordingly, at the age of 14, the younger Brunel was enrolled first at the University of Caen

The University of Caen Normandy (French: ''Université de Caen Normandie''), also known as Unicaen, is a public university in Caen, France.

History

The institution was founded in 1432 by John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, the first rector ...

, then at Lycée Henri-IV

The Lycée Henri-IV is a public secondary school located in Paris. Along with the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, it is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious and demanding sixth-form colleges (''lycées'') in France.

The school educates more than ...

in Paris.Brunel, Isambard (1870), p. 5.

When Brunel was 15, his father, who had accumulated debts of over £5,000, was sent to a debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Historic ...

. After three months went by with no prospect of release, Marc Brunel let it be known that he was considering an offer from the Tsar of Russia

This is a list of all reigning monarchs in the history of Russia. It includes the princes of medieval Rus′ state (both centralised, known as Kievan Rus', Kievan Rus′ and feudal, when the political center moved northeast to Grand Duke of Vl ...

. In August 1821, facing the prospect of losing a prominent engineer, the government relented and issued Marc £5,000 to clear his debts in exchange for his promise to remain in Britain.

When Brunel completed his studies at Henri-IV in 1822, his father had him presented as a candidate at the renowned engineering school École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

, but as a foreigner, he was deemed ineligible for entry. Brunel subsequently studied under the prominent master clockmaker and horologist

Horology (; related to Latin '; ; , interfix ''-o-'', and suffix ''-logy''), . is the study of the measurement of time. Clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic clo ...

Abraham-Louis Breguet

Abraham-Louis Breguet (10 January 1747 – 17 September 1823), born in Neuchâtel, then a Prussian principality, was a horologist who made many innovations in the course of a career in watchmaking industry. He was the founder of the Bregue ...

, who praised Brunel's potential in letters to his father. In late 1822, having completed his apprenticeship, Brunel returned to England.

Thames Tunnel

Brunel worked for several years as an assistant engineer on the project to create a tunnel under London's

Brunel worked for several years as an assistant engineer on the project to create a tunnel under London's River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

between Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe () is a district of south-east London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, as well as the Isle of Dogs ...

and Wapping

Wapping () is a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Wapping's position, on the north bank of the River Thames, has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through its riverside public houses and steps, ...

, with tunnellers driving a horizontal shaft from one side of the river to the other under the most difficult and dangerous conditions. The project was funded by the Thames Tunnel Company and Brunel's father, Marc, was the chief engineer. The ''American Naturalist'' said "It is stated also that the operations of the Teredo hipwormsuggested to Mr. Brunel his method of tunnelling the Thames."

The composition of the riverbed at Rotherhithe was often little more than waterlogged sediment and loose gravel. An ingenious tunnelling shield

A tunnelling shield is a protective structure used during the excavation of large, man-made tunnels. When excavating through ground that is soft, liquid, or otherwise unstable, there is a potential health and safety hazard to workers and the proj ...

designed by Marc Brunel helped protect workers from cave-ins, but two incidents of severe flooding halted work for long periods, killing several workers and badly injuring the younger Brunel. The latter incident, in 1828, killed the two most senior miners, and Brunel himself narrowly escaped death. He was seriously injured and spent six months recuperating. The event stopped work on the tunnel for several years.

Though the Thames Tunnel was eventually completed during Marc Brunel's lifetime, his son had no further involvement with the tunnel proper, only using the abandoned works at Rotherhithe to further his abortive ''Gaz'' experiments. This was based on an idea of his father's and was intended to develop into an engine that ran on power generated from alternately heating and cooling carbon dioxide made from ammonium carbonate and sulphuric acid. Despite interest from several parties (the Admiralty included) the experiments were judged by Brunel to be a failure on the grounds of fuel economy alone, and were discontinued after 1834.

In 1865, the East London Railway Company purchased the Thames Tunnel for £200,000, and four years later the first trains passed through it. Subsequently, the tunnel became part of the London Underground system, and remains in use today, originally as part of the East London Line now incorporated into the London Overground

London Overground (also known simply as the Overground) is a Urban rail in the United Kingdom, suburban rail network serving London and its environs. Established in 2007 to take over Silverlink Metro routes, (via archive.org). it now serves a ...

.Bagust, Harold, "The Greater Genius?", 2006, Ian Allan Publishing, , (pp. 97–100)

Bridges

Brunel is perhaps best remembered for designs for the

Brunel is perhaps best remembered for designs for the Clifton Suspension Bridge

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge and the River Avon, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset. Since opening in 1864, it has been a toll bridge, the income from which provides fun ...

in Bristol, begun in 1831. The bridge was built to designs based on Brunel's, but with significant changes. Spanning over , and nominally above the River Avon, it had the longest span of any bridge in the world at the time of construction. Brunel submitted four designs to a committee headed by Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford FRS, FRSE, (9 August 1757 – 2 September 1834) was a Scottish civil engineer. After establishing himself as an engineer of road and canal projects in Shropshire, he designed numerous infrastructure projects in his native Scotla ...

, but Telford rejected all entries, proposing his own design instead. Vociferous opposition from the public forced the organising committee to hold a new competition, which was won by Brunel.

Afterwards, Brunel wrote to his brother-in-law, the politician Benjamin Hawes

Sir Benjamin Hawes (1797 – 15 May 1862) was a British Whig politician.

Early life

He was a grandson of William Hawes, founder of the Royal Humane Society, and son of Benjamin Hawes of New Barge House, Lambeth, who was a businessman and Fello ...

: "Of all the wonderful feats I have performed, since I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the most wonderful. I produced unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject—taste".

Charles Wetherell

Sir Charles Wetherell (1770 – 17 August 1846) was an English lawyer, politician and judge.

Wetherell was born in Oxford, the third son of Reverend Nathan Wetherell, of Durham, Master of the University College and Vice-Chancellor of the Univer ...

in Clifton. The riots drove away investors, leaving no money for the project, and construction ceased.

Brunel did not live to see the bridge finished, although his colleagues and admirers at the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

felt it would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds and to amend the design. Work recommenced in 1862, three years after Brunel's death, and was completed in 1864. In 2011, it was suggested, by historian and biographer Adrian Vaughan, that Brunel did not design the bridge, as eventually built, as the later changes to its design were substantial. His views reflected a sentiment stated fifty-two years earlier by Tom Rolt

Lionel Thomas Caswall Rolt (usually abbreviated to Tom Rolt or L. T. C. Rolt) (11 February 1910 – 9 May 1974) was a prolific English writer and the biographer of major civil engineering figures including Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Thomas Tel ...

in his 1959 book ''Brunel.'' Re-engineering of suspension chains recovered from an earlier suspension bridge was one of many reasons given why Brunel's design could not be followed exactly.

Hungerford Bridge

The Hungerford Bridge crosses the River Thames in London, and lies between Waterloo Bridge and Westminster Bridge. Owned by Network Rail Infrastructure Ltd (who use its official name of Charing Cross Bridge) it is a steel truss railway bridge ...

, a suspension footbridge across the Thames near Charing Cross Station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashfo ...

in London, was opened in May 1845. Its central span was , and its cost was £106,000. It was replaced by a new railway bridge in 1859, and the suspension chains were used to complete the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge still stands, and over 4 million vehicles traverse it every year.

Brunel designed many bridges for his railway projects, including the Royal Albert Bridge

The Royal Albert Bridge is a railway bridge which spans the River Tamar in England between Plymouth, Devon and Saltash, Cornwall. Its unique design consists of two lenticular iron trusses above the water, with conventional plate-girder app ...

spanning the River Tamar

The Tamar (; kw, Dowr Tamar) is a river in south west England, that forms most of the border between Devon (to the east) and Cornwall (to the west). A part of the Tamar Valley is a World Heritage Site due to its historic mining activities.

T ...

at Saltash

Saltash (Cornish: Essa) is a town and civil parish in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It had a population of 16,184 in 2011 census. Saltash faces the city of Plymouth over the River Tamar and is popularly known as "the Gateway to Corn ...

near Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, Somerset Bridge (an unusual laminated timber-framed bridge near Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a large historic market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. Its population currently stands at around 41,276 as of 2022. Bridgwater is at the edge of the Somerset Levels, in level and well-wooded country. The town lies alon ...

), the Windsor Railway Bridge

Windsor Railway Bridge is a wrought iron ' bow and string' bridge in Windsor, Berkshire, crossing the River Thames on the reach between Romney Lock and Boveney Lock. It carries the branch line between Slough and Windsor.

The Windsor Railway B ...

, and the Maidenhead Railway Bridge

Maidenhead Railway Bridge, also known as Maidenhead Viaduct and The Sounding Arch, carries the Great Western Main Line (GWML) over the River Thames between Maidenhead, Berkshire and Taplow, Buckinghamshire, England. It is a single structure o ...

over the Thames in Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Berk ...

. This last was the flattest, widest brick arch bridge in the world and is still carrying main line trains to the west, even though today's trains are about ten times heavier than in Brunel's time.

Throughout his railway building career, but particularly on the

Throughout his railway building career, but particularly on the South Devon

South Devon is the southern part of Devon, England. Because Devon has its major population centres on its two coasts, the county is divided informally into North Devon and South Devon.For exampleNorth DevonanSouth Devonnews sites. In a narrower se ...

and Cornwall Railway

The Cornwall Railway was a broad gauge railway from Plymouth in Devon to Falmouth in Cornwall, England, built in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was constantly beset with shortage of capital for the construction, and was eventu ...

s where economy was needed and there were many valleys to cross, Brunel made extensive use of wood for the construction of substantial viaducts; these have had to be replaced over the years as their primary material, Kyanised Baltic Pine, became uneconomical to obtain.

Brunel designed the Royal Albert Bridge

The Royal Albert Bridge is a railway bridge which spans the River Tamar in England between Plymouth, Devon and Saltash, Cornwall. Its unique design consists of two lenticular iron trusses above the water, with conventional plate-girder app ...

in 1855 for the Cornwall Railway, after Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

rejected his original plan for a train ferry across the Hamoaze

The Hamoaze (; ) is an estuarine stretch of the tidal River Tamar, between its confluence with the River Lynher and Plymouth Sound, England.

The name first appears as ''ryver of Hamose'' in 1588 and it originally most likely applied just to a ...

—the estuary of the tidal Tamar, Tavy and Lynher. The bridge (of ''bowstring girder'' or ''tied arch'' construction) consists of two main spans of , above mean high spring tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ca ...

, plus 17 much shorter approach spans. Opened by Prince Albert on 2 May 1859, it was completed in the year of Brunel's death.

Several of Brunel's bridges over the Great Western Railway might be demolished because the line is to be electrified, and there is inadequate clearance for overhead wires. Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

County Council is negotiating to have further options pursued, in order that all nine of the remaining historic bridges on the line can be saved.

Brunel's last major undertaking was the unique Three Bridges, London. Work began in 1856, and was completed in 1859.

The three bridges in question are a clever arrangement allowing the routes of the Grand Junction Canal, Great Western and Brentford Railway, and Windmill Lane to cross each other.

Great Western Railway

In the early part of Brunel's life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for goods. This influenced Brunel's involvement in railway engineering, including railway bridge engineering.

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the

In the early part of Brunel's life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for goods. This influenced Brunel's involvement in railway engineering, including railway bridge engineering.

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

, one of the wonders of Victorian Britain, running from London to Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

and later Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

. The company was founded at a public meeting in Bristol in 1833, and was incorporated by Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

in 1835.

It was Brunel's vision that passengers would be able to purchase one ticket at London Paddington and travel from London to New York, changing from the Great Western Railway to the '' Great Western'' steamship at the terminus in Neyland

Neyland is a town and community in Pembrokeshire, Wales, lying on the River Cleddau and the upstream end of the Milford Haven estuary. The Cleddau Bridge carrying the A477 links Pembroke Dock with Neyland.

Etymology

The name of the town is ...

, West Wales. He surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself, with the help of many including his solicitor Jeremiah Osborne of Bristol Law Firm Osborne Clarke

Osborne Clarke is an international legal practice headquartered in London, England with offices in the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Spain, Sweden, France, the Netherlands, China, India via BTG Legal, Singapore, the United States and P ...

who on one occasion rowed Brunel down the River Avon himself to survey the bank of the river for the route. Brunel even designed the Royal Hotel in Bath which opened in 1846 opposite the railway station.

Brunel made two controversial decisions: to use a broad gauge

A broad-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge (the distance between the rails) broader than the used by standard-gauge railways.

Broad gauge of , commonly known as Russian gauge, is the dominant track gauge in former Soviet Union (CIS ...

of for the track, which he believed would offer superior running at high speeds; and to take a route that passed north of the Marlborough Downs

The North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is located in the English counties of Berkshire, Hampshire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire. The name ''North Wessex Downs'' is not a traditional one, the area covered being better k ...

—an area with no significant towns, though it offered potential connections to Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

—and then to follow the Thames Valley into London. His decision to use broad gauge for the line was controversial in that almost all British railways to date had used standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), International gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge and European gauge in Europe, and SGR in Ea ...

. Brunel said that this was nothing more than a carry-over from the mine railways that George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians a great example of diligent application and thirst for ...

had worked on prior to making the world's first passenger railway. Brunel proved through both calculation and a series of trials that his broader gauge was the optimum size for providing both higher speedsPudney, John (1974). ''Brunel and His World''. Thames and Hudson. . and a stable and comfortable ride to passengers. In addition the wider gauge allowed for larger goods wagon

Goods wagons or freight wagons (North America: freight cars), also known as goods carriages, goods trucks, freight carriages or freight trucks, are unpowered railway vehicles that are used for the transportation of cargo. A variety of wagon type ...

s and thus greater freight capacity.

Drawing on Brunel's experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements—soaring

Drawing on Brunel's experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements—soaring viaduct

A viaduct is a specific type of bridge that consists of a series of arches, piers or columns supporting a long elevated railway or road. Typically a viaduct connects two points of roughly equal elevation, allowing direct overpass across a wide v ...

s such as the one in Ivybridge

Ivybridge is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the South Hams, in Devon, England. It lies about east of Andy Hughes’ new house in Ivybridge now he’s forgotten Ugborough. It is at the southern extremity of Dartmoor, a N ...

, specially designed stations, and vast tunnels including the Box Tunnel

Box Tunnel passes through Box Hill on the Great Western Main Line (GWML) between Bath and Chippenham. The tunnel was the world's longest railway tunnel when it was completed in 1841.

Built between December 1838 and June 1841 for the Great W ...

, which was the longest railway tunnel in the world at that time. There is an anecdote claiming that the Box Tunnel was deliberately aligned so that the rising sun shines all the way through it on Brunel's birthday.

The initial group of locomotives ordered by Brunel to his own specifications proved unsatisfactory, apart from the North Star locomotive, and 20-year-old Daniel Gooch

Sir Daniel Gooch, 1st Baronet (24 August 1816 – 15 October 1889) was an English railway locomotive and transatlantic cable engineer. He was the first Superintendent of Locomotive Engines on the Great Western Railway from 1837 to 1864 and ...

(later Sir Daniel) was appointed as Superintendent of Locomotive Engines. Brunel and Gooch chose to locate their locomotive works at the village of Swindon

Swindon () is a town and unitary authority with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Wiltshire, England. As of the 2021 Census, the population of Swindon was 201,669, making it the largest town in the county. The Swindon un ...

, at the point where the gradual ascent from London turned into the steeper descent to the Avon valley at Bath.

Brunel's achievements ignited the imagination of the technically minded Britons of the age, and he soon became quite notable in the country on the back of this interest.

After Brunel's death, the decision was taken that standard gauge should be used for all railways in the country. At the original Welsh terminus of the Great Western railway at Neyland

Neyland is a town and community in Pembrokeshire, Wales, lying on the River Cleddau and the upstream end of the Milford Haven estuary. The Cleddau Bridge carrying the A477 links Pembroke Dock with Neyland.

Etymology

The name of the town is ...

, sections of the broad gauge rails are used as handrails at the quayside, and information boards there depict various aspects of Brunel's life. There is also a larger-than-life bronze statue of him holding a steamship in one hand and a locomotive in the other. The statue has been replaced after an earlier theft.

The present London Paddington station

Paddington, also known as London Paddington, is a Central London railway terminus and London Underground station complex, located on Praed Street in the Paddington area. The site has been the London terminus of services provided by the Great We ...

was designed by Brunel and opened in 1854. Examples of his designs for smaller stations on the Great Western and associated lines which survive in good condition include Mortimer

Mortimer () is an English surname, and occasionally a given name.

Norman origins

The surname Mortimer has a Norman origin, deriving from the village of Mortemer, Seine-Maritime, Normandy. A Norman castle existed at Mortemer from an early point; ...

, Charlbury

Charlbury () is a town and civil parish in the Evenlode

Evenlode is a village and civil parish ( ONS Code 23UC051) in the Cotswold District of eastern Gloucestershire in England.

Evenlode is bordered by the Gloucestershire parishes of More ...

and Bridgend

Bridgend (; cy, Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr or just , meaning "the end of the bridge on the Ogmore") is a town in Bridgend County Borough in Wales, west of Cardiff and east of Swansea. The town is named after the Old Bridge, Bridgend, medieval bridge ...

(all Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style drew its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century Italian R ...

) and Culham

Culham is a village and civil parish in a bend of the River Thames, south of Abingdon in Oxfordshire. The parish includes Culham Science Centre and Europa School UK (formerly the European School, Culham, which was the only Accredited Europe ...

(Tudorbethan

Tudor Revival architecture (also known as mock Tudor in the UK) first manifested itself in domestic architecture in the United Kingdom in the latter half of the 19th century. Based on revival of aspects that were perceived as Tudor architecture ...

). Surviving examples of wooden train shed

A train shed is a building adjacent to a station building where the tracks and platforms of a railway station are covered by a roof. It is also known as an overall roof. Its primary purpose is to store and protect from the elements train car ...

s in his style are at Frome

Frome ( ) is a town and civil parish in eastern Somerset, England. The town is built on uneven high ground at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, and centres on the River Frome. The town, about south of Bath, is the largest in the Mendip d ...

and Kingswear

Kingswear is a village and civil parish in the South Hams area of the English county of Devon. The village is located on the east bank of the tidal River Dart, close to the river's mouth and opposite the small town of Dartmouth. It lies within ...

.

The Swindon Steam Railway Museum

STEAM – Museum of the Great Western Railway, also known as Swindon Steam Railway Museum, is housed in part of the former railway works in Swindon, England – Wiltshire's 'railway town'. The museum opened in 2000.

The site

The museum is ...

has many artefacts from Brunel's time on the Great Western Railway. The Didcot Railway Centre

Didcot Railway Centre is a railway museum and preservation engineering site in Didcot, Oxfordshire, England. The site was formerly a Great Western Railway engine shed and locomotive stabling point.

Background

The founders and commercial backers ...

has a reconstructed segment of track as designed by Brunel and working steam locomotives in the same gauge.

Parts of society viewed the railways more negatively. Some landowners felt the railways were a threat to amenities or property values and others requested tunnels on their land so the railway could not be seen.

Brunel's "atmospheric caper"

Though unsuccessful, another of Brunel's interesting use of technical innovations was the

Though unsuccessful, another of Brunel's interesting use of technical innovations was the atmospheric railway

An atmospheric railway uses differential air pressure to provide power for propulsion of a railway vehicle. A static power source can transmit motive power to the vehicle in this way, avoiding the necessity of carrying mobile power generating eq ...

, the extension of the Great Western Railway (GWR) southward from Exeter towards Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, technically the South Devon Railway (SDR), though supported by the GWR. Instead of using locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the Power (physics), motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, Motor coach (rail), motor ...

s, the trains were moved by Clegg and Samuda's patented system of atmospheric (vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

) traction, whereby stationary pumps sucked the air from a pipe placed in the centre of the track.

The section from Exeter to Newton (now Newton Abbot

Newton Abbot is a market town and civil parish on the River Teign in the Teignbridge District of Devon, England. Its 2011 population of 24,029 was estimated to reach 26,655 in 2019. It grew rapidly in the Victorian era as the home of the Sou ...

) was completed on this principle, and trains ran at approximately .Dumpleton and Miller (2002), p. 22 Pumping stations with distinctive square chimneys were sited at two-mile intervals. Fifteen-inch (381 mm) pipes were used on the level portions, and pipes were intended for the steeper gradients.

The technology required the use of leather flaps to seal the vacuum pipes. The natural oils were drawn out of the leather by the vacuum, making the leather vulnerable to water, rotting it and breaking the fibres when it froze during the winter of 1847. It had to be kept supple with tallow

Tallow is a rendering (industrial), rendered form of beef or mutton fat, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton fat. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain techn ...

, which is attractive to rats. The flaps were eaten, and vacuum operation lasted less than a year, from 1847 (experimental service began in September; operations from February 1848) to 10 September 1848. Deterioration of the valve due to the reaction of tannin

Tannins (or tannoids) are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids.

The term ''tannin'' (from Anglo-Norman ''tanner'', ...

and iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of whic ...

has been cited as the last straw that sank the project, as the continuous valve began to tear from its rivets over most of its length, and the estimated replacement cost of £25,000 was considered prohibitive.

The system never managed to prove itself. The accounts of the SDR for 1848 suggest that atmospheric traction cost 3s 1d (three shillings and one penny) per mile compared to 1s 4d/mile for conventional steam power (because of the many operating issues associated with the atmospheric, few of which were solved during its working life, the actual cost efficiency proved impossible to calculate). Several South Devon Railway engine houses

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

still stand, including that at Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-so ...

(scheduled as a grade II listed monument in 2007) and at Starcross

Starcross is a village with a 2011 census recorded population of 1,737 situated on the west shore of the Exe Estuary in Teignbridge in the English county of Devon. The village is popular in summer with leisure craft, and is home to one of t ...

.

A section of the pipe, without the leather covers, is preserved at the Didcot Railway Centre

Didcot Railway Centre is a railway museum and preservation engineering site in Didcot, Oxfordshire, England. The site was formerly a Great Western Railway engine shed and locomotive stabling point.

Background

The founders and commercial backers ...

.

In 2017, inventor Max Schlienger unveiled a working model of an updated atmospheric railroad at his vineyard in the Northern California town of Ukiah.

Transatlantic shipping

Brunel had proposed extending its transport network by boat from Bristol across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City before the Great Western Railway opened in 1835. The

Brunel had proposed extending its transport network by boat from Bristol across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City before the Great Western Railway opened in 1835. The Great Western Steamship Company

The Great Western Steam Ship Company operated the first regular transatlantic steamer service from 1838 until 1846. Related to the Great Western Railway, it was expected to achieve the position that was ultimately secured by the Cunard Line. Th ...

was formed by Thomas Guppy for that purpose. It was widely disputed whether it would be commercially viable for a ship powered purely by steam to make such long journeys. Technological developments in the early 1830s—including the invention of the surface condenser

A surface condenser is a water-cooled shell and tube heat exchanger installed to condense exhaust steam from a steam turbine in thermal power stations. These condensers are heat exchangers which convert steam from its gaseous to its liquid stat ...

, which allowed boilers to run on salt water without stopping to be cleaned—made longer journeys more possible, but it was generally thought that a ship would not be able to carry enough fuel for the trip and have room for commercial cargo. Brunel applied the experimental evidence of Beaufoy and further developed the theory that the amount a ship could carry increased as the cube of its dimensions, whereas the amount of resistance a ship experienced from the water as it travelled increased by only a square of its dimensions. This would mean that moving a larger ship would take proportionately less fuel than a smaller ship. To test this theory, Brunel offered his services for free to the Great Western Steamship Company, which appointed him to its building committee and entrusted him with designing its first ship, the .Beckett (2006), pp. 171–73

When it was built, the ''Great Western'' was the longest ship in the world at with a

When it was built, the ''Great Western'' was the longest ship in the world at with a keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

. The ship was constructed mainly from wood, but Brunel added bolts and iron diagonal reinforcements to maintain the keel's strength. In addition to its steam-powered paddle wheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

s, the ship carried four masts for sails. The ''Great Western'' embarked on her maiden voyage from Avonmouth

Avonmouth is a port and outer suburb of Bristol, England, facing two rivers: the reinforced north bank of the final stage of the Avon which rises at sources in Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Somerset; and the eastern shore of the Severn Estuar ...

, Bristol, to New York on 8 April 1838 with of coal, cargo and seven passengers on board. Brunel himself missed this initial crossing, having been injured during a fire aboard the ship as she was returning from fitting out in London. As the fire delayed the launch several days, the ''Great Western'' missed its opportunity to claim the title as the first ship to cross the Atlantic under steam power alone. Even with a four-day head start, the competing arrived only one day earlier, having virtually exhausted its coal supply. In contrast, the ''Great Western'' crossing of the Atlantic took 15 days and five hours, and the ship arrived at her destination with a third of its coal still remaining, demonstrating that Brunel's calculations were correct. The ''Great Western'' had proved the viability of commercial transatlantic steamship service, which led the Great Western Steamboat Company to use her in regular service between Bristol and New York from 1838 to 1846. She made 64 crossings, and was the first ship to hold the Blue Riband

The Blue Riband () is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. T ...

with a crossing time of 13 days westbound and 12 days 6 hours eastbound. The service was commercially successful enough for a sister ship to be required, which Brunel was asked to design.

Brunel had become convinced of the superiority of propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

-driven ships over paddle wheels. After tests conducted aboard the propeller-driven steamship , he incorporated a large six-bladed propeller into his design for the , which was launched in 1843. ''Great Britain'' is considered the first modern ship, being built of metal rather than wood, powered by an engine rather than wind or oars, and driven by propeller rather than paddle wheel. She was the first iron-hulled, propeller-driven ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Her maiden voyage was made in August and September 1845, from Liverpool to New York. In 1846, she was run aground at Dundrum, County Down

Dundrum () is a village and townland in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is beside Dundrum Bay, about 4 miles outside Newcastle, County Down, Newcastle on the A2 road. The village is best known for its ruined Norman architecture, Norman Dundru ...

. She was salvaged and employed in the Australian service. She is currently fully preserved and open to the public in Bristol, UK.

In 1852 Brunel turned to a third ship, larger than her predecessors, intended for voyages to India and Australia. The (originally dubbed ''Leviathan'') was cutting-edge technology for her time: almost long, fitted out with the most luxurious appointments, and capable of carrying over 4,000 passengers. ''Great Eastern'' was designed to cruise non-stop from London to Sydney and back (since engineers of the time mistakenly believed that Australia had no coal reserves), and she remained the largest ship built until the start of the 20th century. Like many of Brunel's ambitious projects, the ship soon ran over budget and behind schedule in the face of a series of technical problems. The ship has been portrayed as a white elephant

A white elephant is a possession that its owner cannot dispose of, and whose cost, particularly that of maintenance, is out of proportion to its usefulness. In modern usage, it is a metaphor used to describe an object, construction project, sch ...

, but it has been argued by David P. Billington that in this case, Brunel's failure was principally one of economics—his ships were simply years ahead of their time. His vision and engineering innovations made the building of large-scale, propeller-driven, all-metal steamships a practical reality, but the prevailing economic and industrial conditions meant that it would be several decades before transoceanic steamship travel emerged as a viable industry.

''Great Eastern'' was built at John Scott Russell

John Scott Russell FRSE FRS FRSA (9 May 1808, Parkhead, Glasgow – 8 June 1882, Ventnor, Isle of Wight) was a Scottish civil engineer, naval architect and shipbuilder who built '' Great Eastern'' in collaboration with Isambard Kingdom Brunel. ...

's Napier Yard in London, and after two trial trips in 1859, set forth on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on 17 June 1860. Though a failure at her original purpose of passenger travel, she eventually found a role as an oceanic telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

cable-layer. Under Captain Sir James Anderson, the ''Great Eastern'' played a significant role in laying the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data a ...

, which enabled telecommunication between Europe and North America.

Renkioi Hospital

Britain entered into theCrimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

during 1854 and an old Turkish barracks became the British Army Hospital in Scutari. Injured men contracted a variety of illnesses—including cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

and malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

—due to poor conditions there, and Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

sent a plea to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' for the government to produce a solution.

Brunel was working on the ''Great Eastern'' amongst other projects but accepted the task in February 1855 of designing and building the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

requirement of a temporary, pre-fabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. The term is ...

hospital that could be shipped to Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

and erected there. In five months the team he had assembled designed, built, and shipped pre-fabricated wood and canvas buildings, providing them complete with advice on transportation and positioning of the facilities.

Brunel had been working with Gloucester Docks

Gloucester Docks is an historic area of the city of Gloucester. The docks are located at the northern junction of the River Severn with the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal. They are Britain's most inland port.

The docks include fifteen Victoria ...

-based William Eassie William Eassie (1805-1861) was a prominent Scottish businessman of the mid 19th century, working as a railway contractor and then as a Gloucester-based supplier of prefabricated wooden buildings.

Career

Eassie was born at Lochee near Dundee in 180 ...

on the launching stage for the ''Great Eastern''. Eassie had designed and built wooden prefabricated huts used in both the Australian gold rush, as well as by the British and French Armies in the Crimea. Using wood supplied by timber importers Price & Co., Eassie fabricated 18 of the 50-patient wards designed by Brunel, shipped directly via 16 ships from Gloucester Docks to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. The Renkioi Hospital

Renkioi Hospital was a pioneering prefabricated building made of wood, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel as a British Army military hospital for use during the Crimean War.

Background

During 1854 Britain entered into the Crimean War, and the ...

was subsequently erected near Scutari Hospital, where Nightingale was based, in the malaria-free area of Renkioi.. ''Hospital Development Magazine''. 10 November 2005. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

His designs incorporated the necessities of hygiene

Hygiene is a series of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

: access to sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

, ventilation, drainage, and even rudimentary temperature controls. They were feted as a great success, with some sources stating that of the approximately 1,300 patients treated in the hospital, there were only 50 deaths. In the Scutari hospital it replaced, deaths were said to be as many as ten times this number. Nightingale referred to them as "those magnificent huts". The practice of building hospitals from pre-fabricated modules survives today, with hospitals such as the Bristol Royal Infirmary

The Bristol Royal Infirmary, also known as the BRI, is a large teaching hospital situated in the centre of Bristol, England. It has links with the nearby University of Bristol and the Faculty of Health and Social Care at the University of the Wes ...

being created in this manner.

Personal life

On 10 June 1830 Brunel was elected aFellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

.

Brunel married Mary Elizabeth Horsley (b. 1813) on 5 July 1836. She came from an accomplished musical and artistic family, being the eldest daughter of composer and organist William Horsley

William Horsley (18 November 177412 June 1858) was an English musician. His compositions were numerous, and include amongst other instrumental pieces three symphonies for full orchestra. More important are his glees, of which he published f ...

. They established a home at Duke Street, Westminster, in London.

While performing a conjuring trick for the amusement of his children in 1843 Brunel accidentally inhaled a

While performing a conjuring trick for the amusement of his children in 1843 Brunel accidentally inhaled a half-sovereign

The half sovereign is a British gold coin with a nominal value of half of one pound sterling. It is half the weight (and has half the gold content) of its counterpart 'full' sovereign coin.

The half sovereign was first introduced in 1544 under He ...

coin, which became lodged in his windpipe. A special pair of forceps

Forceps (plural forceps or considered a plural noun without a singular, often a pair of forceps; the Latin plural ''forcipes'' is no longer recorded in most dictionaries) are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Fo ...

failed to remove it, as did a machine devised by Brunel to shake it loose. At the suggestion of his father, Brunel was strapped to a board and turned upside-down, and the coin was jerked free. He recuperated at Teignmouth

Teignmouth ( ) is a seaside town, fishing port and civil parish in the English county of Devon. It is situated on the north bank of the estuary mouth of the River Teign, about 12 miles south of Exeter. The town had a population of 14,749 at the ...

, and enjoyed the area so much that he purchased an estate at Watcombe in Torquay

Torquay ( ) is a seaside town in Devon, England, part of the unitary authority area of Torbay. It lies south of the county town of Exeter and east-north-east of Plymouth, on the north of Tor Bay, adjoining the neighbouring town of Paignton ...

, Devon. Here he commissioned William Burn to design Brunel Manor

Brunel Manor, previously known as Watcombe Park, is a mansion on the outskirts of the seaside resort of Torquay, Devon, England.

Ownership history

The manor and its gardens were designed by William Burn to be the retirement home of Isambard K ...

and its gardens to be his country home. He never saw the house or gardens finished as he died before it was completed.

Brunel, a heavy smoker, who had been diagnosed with Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied b ...

(nephritis

Nephritis is inflammation of the kidneys and may involve the glomeruli, tubules, or interstitial tissue surrounding the glomeruli and tubules. It is one of several different types of nephropathy.

Types

* Glomerulonephritis is inflammation of th ...

), suffered a stroke on 5 September 1859, just before the ''Great Eastern'' made her first voyage to New York. He died ten days later at the age of 53 and was buried, like his father, in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederic ...

, London. He is commemorated at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

in a window on the south side of the nave. Many mourned Brunel's passing, in spite and because of his business ventures; an obituary in ''The Morning Chronicle

''The Morning Chronicle'' was a newspaper founded in 1769 in London. It was notable for having been the first steady employer of essayist William Hazlitt as a political reporter and the first steady employer of Charles Dickens as a journalist. It ...

'' noted:

Brunel was the right man for the nation, but unfortunately, he was not the right man for the shareholders. They must stoop who must gather gold, and Brunel could never stoop. The history of invention records no instance of grand novelties so boldly imagined and so successfully carried out by the same individual.Brunel was survived by his wife, Mary, and three children:

Isambard Brunel Junior Isambard is a given name. It is Norman, of Germanic origin, meaning either "iron-bright" or "iron-axe". The first element comes from ''isarn'' meaning iron (or steel). The second element comes from either ''biart-r'' (bright, glorious) or from ''ba ...

(1837–1902), Henry Marc Brunel

Henry Marc Brunel (27 June 1842 – 7 October 1903) was an English civil engineer and the son of the celebrated engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel and grandson of civil engineer Marc Isambard Brunel.

Henry Marc Brunel was born in Westminster, Lo ...

(1842–1903) and Florence Mary Brunel (1847–1876). Henry Marc later became a successful civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

.

Legacy

A celebrated engineer in his era, Brunel remains revered today, as evidenced by numerous monuments to him. There are statues in London at

A celebrated engineer in his era, Brunel remains revered today, as evidenced by numerous monuments to him. There are statues in London at Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

(pictured), Brunel University

Brunel University London is a public research university located in the Uxbridge area of London, England. It was founded in 1966 and named after the Victorian engineer and pioneer of the Industrial Revolution, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. In June 1 ...

and Paddington station, and in Bristol, Plymouth, Swindon, Milford Haven and Saltash. A statue in Neyland

Neyland is a town and community in Pembrokeshire, Wales, lying on the River Cleddau and the upstream end of the Milford Haven estuary. The Cleddau Bridge carrying the A477 links Pembroke Dock with Neyland.

Etymology

The name of the town is ...

in Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

was stolen in August 2010. The topmast of the ''Great Eastern'' is used as a flagpole at the entrance to Anfield

Anfield is a football stadium in Anfield, Liverpool, Merseyside, England, which has a seating capacity of 53,394, making it the seventh largest football stadium in England. It has been the home of Liverpool F.C. since their formation in 1892. ...

, Liverpool Football Club's ground. Contemporary locations bear Brunel's name, such as Brunel University

Brunel University London is a public research university located in the Uxbridge area of London, England. It was founded in 1966 and named after the Victorian engineer and pioneer of the Industrial Revolution, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. In June 1 ...

in London, shopping centres in Swindon

Swindon () is a town and unitary authority with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Wiltshire, England. As of the 2021 Census, the population of Swindon was 201,669, making it the largest town in the county. The Swindon un ...

and also Bletchley, Milton Keynes

Bletchley is a constituent town of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. It is situated in the south-west of Milton Keynes, and is split between the civil parishes of Bletchley and Fenny Stratford and West Bletchley.

Bletchley is best known ...

, and a collection of streets in Exeter: Isambard Terrace, Kingdom Mews, and Brunel Close. A road, car park, and school in his home city of Portsmouth are also named in his honour, along with one of the city's largest public houses. There is an engineering lab building at the University of Plymouth named in his honour.

A public poll conducted by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...100 Greatest Britons

''100 Greatest Britons'' is a television series that was broadcast by the BBC in 2002. It was based on a television poll conducted to determine who the British people at that time considered the greatest Britons in history. The series included in ...

, Brunel was placed second, behind Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. Brunel's life and works have been depicted in numerous books, films and television programs. The 2003 book and BBC TV series ''Seven Wonders of the Industrial World

''Seven Wonders of the Industrial World'' is a 7-part British docudrama television miniseries that originally aired from to on BBC and was later released on DVD. The programme examines seven engineering feats that occurred since the Industri ...

'' included a dramatisation of the building of the ''Great Eastern''.

Many of Brunel's bridges are still in use. Brunel's first engineering project, the Thames Tunnel, is now part of the London Overground

London Overground (also known simply as the Overground) is a Urban rail in the United Kingdom, suburban rail network serving London and its environs. Established in 2007 to take over Silverlink Metro routes, (via archive.org). it now serves a ...

network. The Brunel Engine House

The Brunel Museum is a small museum situated at the Brunel Engine House, Rotherhithe, London Borough of Southwark. The Engine House was designed by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel as part of the infrastructure of the Thames Tunnel which opened in 1843 ...

at Rotherhithe, which once housed the steam engines that powered the tunnel pumps, now houses the Brunel Museum

The Brunel Museum is a small museum situated at the Brunel Engine House, Rotherhithe, London Borough of Southwark. The Engine House was designed by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel as part of the infrastructure of the Thames Tunnel which opened in 1843 ...

dedicated to the work and lives of Henry Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Many of Brunel's original papers and designs are now held in the Brunel Institute alongside the in Bristol, and are freely available for researchers and visitors.

Brunel is credited with turning the town of Swindon into one of the fastest-growing towns in Europe during the 19th century. Brunel's choice to locate the Great Western Railway locomotive sheds there caused a need for housing for the workers, which in turn gave Brunel the impetus to build hospitals, churches and housing estates in what is known today as the 'Railway Village'. According to some sources, Brunel's addition of a Mechanics Institute for recreation and hospitals and clinics for his workers gave Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party politician, noted for tenure as Minister of Health in Clement Attlee's government in which he spearheaded the creation of the British National Health ...

the basis for the creation of the National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

.

GWR Castle Class

The 4073 or Castle Class are 4-6-0 steam locomotives of the Great Western Railway, built between 1923 and 1950. They were designed by the railway's Chief Mechanical Engineer, Charles Collett, for working the company's express passenger trains. ...

steam locomotive no. 5069 was named ''Isambard Kingdom Brunel'', after the engineer; and BR Western Region class 47 diesel locomotive no. D1662 (later 47484) was also named ''Isambard Kingdom Brunel''. GWR's successor Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran ...

has named both its old InterCity 125

The InterCity 125 (originally Inter-City 125New trai ...

power car 43003 and new InterCity Electric Train 800004 as ''Isambard Kingdom Brunel''.

The Royal Mint

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's oldest company and the official maker of British coins.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a limited company that is wholly owned by His Majesty's Treasury and is under an exclus ...

struck two £2 coin

The United Kingdom, British two pound (£2) coin is a denomination of Coins of the United Kingdom, sterling coinage. Its obverse has featured the profile of Queen Elizabeth II since the coin’s introduction. Three different portraits of the Quee ...

s in 2006 to "celebrate the 200th anniversary of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his achievements". The first depicts Brunel with a section of the Royal Albert Bridge

The Royal Albert Bridge is a railway bridge which spans the River Tamar in England between Plymouth, Devon and Saltash, Cornwall. Its unique design consists of two lenticular iron trusses above the water, with conventional plate-girder app ...

and the second shows the roof of Paddington Station. In the same year the Post Office issued a set of six wide commemorative stamps (SG 2607-12) showing the Royal Albert Bridge

The Royal Albert Bridge is a railway bridge which spans the River Tamar in England between Plymouth, Devon and Saltash, Cornwall. Its unique design consists of two lenticular iron trusses above the water, with conventional plate-girder app ...

, the Box Tunnel

Box Tunnel passes through Box Hill on the Great Western Main Line (GWML) between Bath and Chippenham. The tunnel was the world's longest railway tunnel when it was completed in 1841.

Built between December 1838 and June 1841 for the Great W ...

, Paddington Station

Paddington, also known as London Paddington, is a Central London railway terminus and London Underground station complex, located on Praed Street in the Paddington area. The site has been the London terminus of services provided by the Great We ...

, the ''Great Eastern,'' the Clifton Suspension Bridge

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge and the River Avon, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset. Since opening in 1864, it has been a toll bridge, the income from which provides fun ...

, and the Maidenhead Bridge

Maidenhead Bridge is a Grade I listed bridge carrying the A4 road over the River Thames between Maidenhead, Berkshire and Taplow, Buckinghamshire, England. It crosses the Thames on the reach above Bray Lock, about half a mile below Boulter's ...

.

The words "I.K. BRUNEL ENGINEER 1859" were fixed to either end of the Royal Albert Bridge

The Royal Albert Bridge is a railway bridge which spans the River Tamar in England between Plymouth, Devon and Saltash, Cornwall. Its unique design consists of two lenticular iron trusses above the water, with conventional plate-girder app ...

to commemorate his death in 1859, the year the bridge opened. The words were later partly obscured by maintenance access ladders but were revealed again by Network Rail