Brooke-Popham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Air Chief Marshal Sir Henry Robert Moore Brooke-Popham, (18 September 1878 – 20 October 1953) was a senior commander in the

Brooke-Popham was born in England in the Suffolk village of

Brooke-Popham was born in England in the Suffolk village of

Brooke-Popham was attached to

Brooke-Popham was attached to

With the establishment of the

With the establishment of the

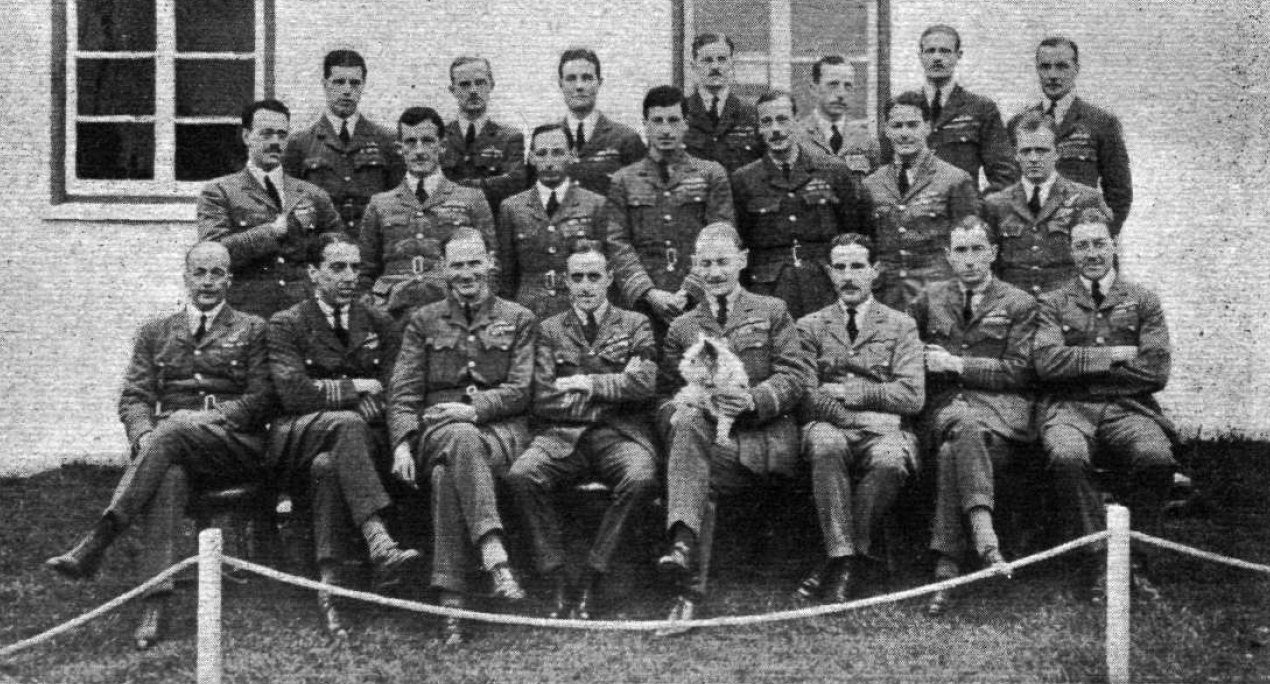

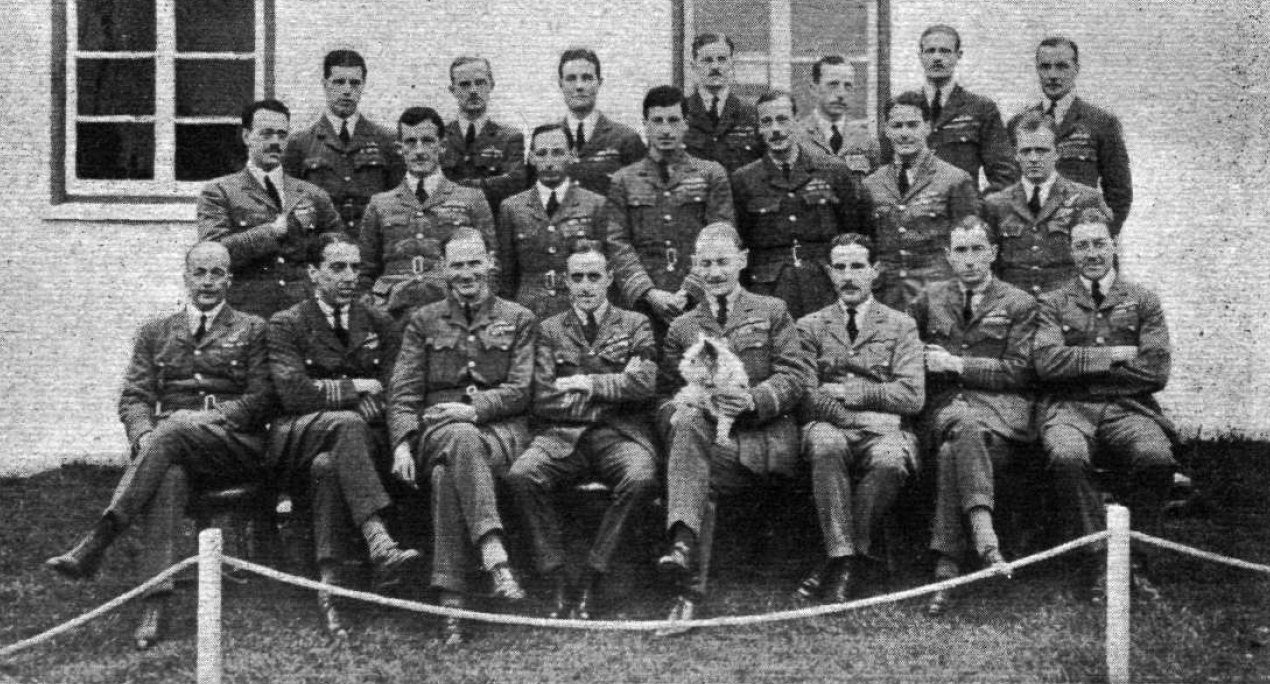

From 1919 to 1921, Brooke-Popham served as Director of Research at the Air Ministry and in November 1921 he was tasked with establishing the RAF Staff College at Andover and he became its first commandant on 1 April 1922.

In 1925 the

From 1919 to 1921, Brooke-Popham served as Director of Research at the Air Ministry and in November 1921 he was tasked with establishing the RAF Staff College at Andover and he became its first commandant on 1 April 1922.

In 1925 the

Sir Robert Brooke-Popham

Flight International, 30 October 1953

Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King's College London, 2005. p. 2.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – Sir (Henry) Robert Moore Brooke-Popham

(requires login) , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke-Popham, Robert 1878 births 1953 deaths People from Mid Suffolk District Knights Bachelor Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst People educated at Haileybury and Imperial Service College Colonial governors and administrators of Kenya British Army personnel of the Second Boer War Military of Singapore under British rule Royal Flying Corps officers British Army generals of World War I Royal Air Force generals of World War I Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Knights of the Order of St John Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Collections of the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Burials in Somerset Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry officers Military personnel from Suffolk

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he served in the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

as a wing commander and senior staff officer. Remaining in the new Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) after the war, Brooke-Popham was the first commandant of its Staff College at Andover and later held high command in the Middle East. He was Governor of Kenya

This article contains a list of chairmen, administrators, commissioners and governors of British Kenya Colony.

The office of Governor of Kenya was replaced by the office of Governor General in 1963 and then later replaced by a President of Kenya ...

in the late 1930s. Most notably, Brooke-Popham was Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command

The Far East Command was a British military command which had 2 distinct periods. These were firstly, 18 November 1940 – 7 January 1942 succeeded by the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command ( ABDACOM), and secondly, 1963–1971 succeeded ...

until being replaced a few weeks before Singapore fell to Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

troops.

Family life and education

Brooke-Popham was born in England in the Suffolk village of

Brooke-Popham was born in England in the Suffolk village of Mendlesham

Mendlesham is a village in Suffolk with 1,407 inhabitants at the 2011 census. It lies north east of Stowmarket and from London.

The place-name 'Mendlesham' is first attested in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it appears as ''Melnesham'' an ...

on 18 September 1878. His parents were Henry Brooke, a country gentleman of Wetheringsett Manor in Suffolk, and his wife Dulcibella who was the daughter of Robert Moore, a clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

man.

Brooke-Popham's education was not atypical of a man entering the British officer class. He attended South Lodge School in Lowestoft from 1885 to 1891. After his school years at Haileybury and his officer training at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC), founded in 1801 and established in 1802 at Great Marlow and High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England, but moved in October 1812 to Sandhurst, Berkshire, was a British Army military academy for training infant ...

, he was commissioned into the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

in 1898. In January 1926, Brooke-Popham married Opal Mary, the daughter of Edgar Hugonin. They later had a son and a daughter.

Early military career

After graduating from Sandhurst in May 1898, Brooke-Popham wasgazetted

A gazette is an official journal, a newspaper of record, or simply a newspaper.

In English and French speaking countries, newspaper publishers have applied the name ''Gazette'' since the 17th century; today, numerous weekly and daily newspapers ...

to the Oxfordshire Light Infantry

The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry was a light infantry regiment of the British Army that existed from 1881 until 1958, serving in the Second Boer War, World War I and World War II.

The regiment was formed as a consequence of th ...

in the rank of second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

, and the following year promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

on 24 November 1899. As a subaltern

Subaltern may refer to:

*Subaltern (postcolonialism), colonial populations who are outside the hierarchy of power

* Subaltern (military), a primarily British and Commonwealth military term for a junior officer

* Subalternation, going from a univer ...

he saw active service in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

during 1899 and 1900 and on 26 April 1902 he was seconded for further duty in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

. During his time there he served in the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

, the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

, the Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Unio ...

, and Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

. He was promoted captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 9 November 1904. By 1910 Brooke-Popham had returned to Great Britain. From 22 January 1910, he attended the Army Staff College at Camberley.

Military aviation before the First World War

Brooke-Popham was attached to

Brooke-Popham was attached to Air Battalion Royal Engineers

The Air Battalion Royal Engineers (ABRE) was the first flying unit of the British Armed Forces to make use of heavier-than-air craft. Founded in 1911, the battalion in 1912 became part of the Royal Flying Corps, which in turn evolved into the Roy ...

during its manoeuvres of 1911, after which he decided to learn to fly. He attended the flying school at Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfie ...

and gained Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

certificate number 108 in July 1911. He returned to his regiment, the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry was a light infantry regiment of the British Army that existed from 1881 until 1958, serving in the Second Boer War, World War I and World War II.

The regiment was formed as a consequence of th ...

, on 28 February 1912. However, in early 1912 he transferred to the Air Battalion, taking up duties as a pilot in March. The next month, Brooke-Popham was appointed Officer Commanding of the Battalion's Aeroplane Company.

With the creation of the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

(RFC) from the Air Battalion on 13 May 1912, Brooke-Popham was transferred to the RFC. He was appointed the first Officer Commanding of No. 3 Squadron. In a letter to the editor of ''Flight'' magazine, dated 23 January 1949, he wrote, "I see from an old log book that though I was seconded to the Air Battalion at the end of March 1912, it was not till the 6th May that I flew to Larkhill to take over command of No.2 (Aeroplane) Co." No. 3 Squadron was the successor unit to the Air Battalion's No. 2 (Aeroplane) Company which had been stationed at Larkhill, on Salisbury Plain, since its creation in April 1911 and thus became the oldest British, Empire or Commonwealth independent military unit to operate heavier-than-air machines.

First World War

Following the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Brooke-Popham went to France as the Deputy Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster-General in the headquarters of the Royal Flying Corps, where he was responsible for the administrative and technical support to the squadrons deployed in the field. His understanding of the importance of air power and its support to land forces led him to criticize the lack of adequate air support to the British Expeditionary Force.

On 20 November 1914 Brooke-Popham was appointed Officer Commanding No. 3 Wing of the RFC. At this time the wing consisted of No. 1 and No. 4 squadrons, and on the same day as his appointment, Brooke-Popham received a temporary promotion to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

. During the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge a ...

, Brooke-Popham directed his Wing's operations and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

for his part in the Battle.

By 1915, Brooke-Popham was too senior an officer to take part in much operational flying, and he also had limited experience of air combat. Rather, his energies were directed into administrative and organizational activities, as he served in several staff posts at the RFC's headquarters in France. In May 1915 Brooke-Popham was appointed the RFC's Chief Staff Officer, and in March 1916 he was the Corps' Deputy Adjutant and Quartermaster-General, which saw him granted the temporary rank of brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

.

In 1915, the capabilities of radio were still very limited. Observers in aircraft could not easily communicate with men on the ground. Men on the ground could not easily reply. In 1915, a technique was developed whereby troops on the ground could send messages to aviators by laying strips of white cloth on the ground. These strips are referred to as "Popham strips" in a novel set in the period.

With the establishment of the

With the establishment of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

in April 1918, Brooke-Popham was transferred to the newly created Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. He served as the Controller of Aircraft Production for the remainder of the War and for some months afterwards. In 1919 he served as Director of Aircraft Research.

Developed during the First World War, the Popham panel was named for him.

RAF service during the inter-war years

Post-war honours

Following the end of the First World War, Brooke-Popham was decorated for his contributions to the war effort. In January 1919 he was awarded the Air Force Cross and made aCompanion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, George III, King George III.

...

. Later in the same year he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

and was given a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force as a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

. He was rapidly promoted to air commodore when the Air Force introduced its own rank system in August 1919.

Career progression

From 1919 to 1921, Brooke-Popham served as Director of Research at the Air Ministry and in November 1921 he was tasked with establishing the RAF Staff College at Andover and he became its first commandant on 1 April 1922.

In 1925 the

From 1919 to 1921, Brooke-Popham served as Director of Research at the Air Ministry and in November 1921 he was tasked with establishing the RAF Staff College at Andover and he became its first commandant on 1 April 1922.

In 1925 the Air Defence of Great Britain

The Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB) was a RAF command comprising substantial army and RAF elements responsible for the air defence of the British Isles. It lasted from 1925, following recommendations that the RAF take control of homeland air ...

had been created and it was charged with defending the United Kingdom from aerial attack. The following year, Brooke-Popham was posted as Air Officer Commanding (AOC) the Fighting Area within the Air Defence of Great Britain and he served in this capacity for the next two years. During his time as AOC Fighting Area, Brooke-Popham oversaw the establishment of a chain of huge concrete mirrors which were designed for acoustic early warning and he received a knighthood in 1927.

On 1 November 1928, Brooke-Popham was appointed AOC Iraq Command. This high-profile position put him in charge of all British forces in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and, when the post of high commissioner was vacant, he acted in that capacity as well. In late 1928, he mobilised and despatched the Victoria aircraft for the rescue of British embassy staff and others in the Kabul evacuation by air operation.

The start of 1931 saw Brooke-Popham promoted to air marshal and then posted as the first RAF officer to serve as Commandant of the Imperial Defence College. Two years later in 1933, he returned to the Air Defence of Great Britain, this time in the senior post of Air Officer Commander-in-Chief. Later that year Brooke-Popham received the honorary appointment of Principal Aide-de-Camp to the King. In 1935 he left the Air Defence of Great Britain to become the Inspector-General of the RAF

The Inspector-General of the RAF was a senior appointment in the Royal Air Force, responsible for the inspection of airfields. The post existed from 1918 to 1920 and from 1935 until the late 1960s. For much of World War II, a second inspector-ge ...

. This was, however, a short-lived appointment and he was posted later that year.

Commander-in-Chief RAF Middle East

In late 1935, Brooke-Popham took up the post of Air Officer Commander-in-Chief RAF Middle East with his headquarters inCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

. His appointment took place not long after the outbreak of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War in October 1935 and his principal aim was to deter the '' Regia Aeronautica'' from attacking British territory in north east Africa. In 1937, Brooke-Popham relinquished his command and returned to Great Britain, retiring from the RAF on 6 March.

Governor of Kenya

Following Italy'soccupation

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

of Ethiopia, the British Government wanted a military man to hold the post of Governor of Kenya

This article contains a list of chairmen, administrators, commissioners and governors of British Kenya Colony.

The office of Governor of Kenya was replaced by the office of Governor General in 1963 and then later replaced by a President of Kenya ...

. Brooke-Popham was appointed Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Kenya in 1937 and his military expertise was useful in helping the colony prepare for a possible war with Italy. Under his direction, a plan was devised which concentrated defensive resources on the strategically important port of Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, which was judged to be the most likely Italian target. Although this left Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ha ...

and the highlands with only limited defences, the barren regions of northern Kenya meant that the inland settlements were geographically protected from the Italian threat further to the north. Eventually, as the Italian occupation of Ethiopia was characterized by strife and unrest, the threat to Kenya dissipated.

Brooke-Popham's governorship was also marked by improved relations with the settlers. His predecessor had sought to dominate the political and economic life of the colony which had aroused repeated opposition from some of the settlers' leaders. However, in courting settler opinion, some historians have criticized Brooke-Popham for failing to deal with those settlers who wanted to limit African and Asian freedoms in Kenya.

In 1939 on the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Brooke-Popham ordered the internment of all Germans in Kenya, directed that all aircraft be commandeered, and devised a plan to keep the colony's farms running. On 30 September 1939 he relinquished the governorship and returned to Britain.

Second World War

Commonwealth Air Training Plan

Brooke-Popham rejoined the RAF shortly after his return to Great Britain and only weeks after the outbreak of the Second World War. He was first appointed as head of the RAF's training mission toCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

where he worked on the establishment of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan. In 1940 Brooke-Popham was made head of the training mission to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

where he continued work on the Plan.

Commander-in-Chief Far East Command

Command arrangements

On 18 November 1940, at the age of 62, Brooke-Popham was appointed Commander-in-Chief of theBritish Far East Command

The Far East Command was a British military command which had 2 distinct periods. These were firstly, 18 November 1940 – 7 January 1942 succeeded by the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command ( ABDACOM), and secondly, 1963–1971 succeeded ...

making him responsible for defence matters in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, Malaya, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

. This was a considerably more demanding undertaking than any of Brooke-Popham's many previous appointments. The Command

Command may refer to:

Computing

* Command (computing), a statement in a computer language

* COMMAND.COM, the default operating system shell and command-line interpreter for DOS

* Command key, a modifier key on Apple Macintosh computer keyboards

* ...

had been newly created and Brooke-Popham was the first RAF officer to be appointed Commander-in-Chief of a joint command during a major world conflict. Additionally, there was a significant gap between the Commander-in-Chief's responsibility and his authority, as Brooke-Popham was nominally responsible for all defence matters in the British Far East colonies but the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

units in these waters did not come under his command; rather they reported to their own naval commander-in-chief in London. Furthermore, the civil servants in the Far East also did not report to the Commander-in-Chief, working instead for ministers in London.

Insufficient defences

With the Japanese threatening south-east Asia, Brooke-Popham knew he had to build up the defences of the region. Those defences which already existed were primarily directed towards an attack from the sea and everywhere sufficient forces were lacking. The Command's aerial defences were particularly deficient and the priority attached to operations in theMiddle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

meant that British resources were directed elsewhere. During the following year, Brooke-Popham struggled without much success to build up defences, get the much-needed reinforcements and rectify the unsound command arrangements.

Operation ''Matador''

In August 1941 Brooke-Popham submitted a plan for the defence of Malaya to London for approval. This plan, code-named ''Matador'', worked on the basis that the Japanese would land on the east coast ofThailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

and then advance south. The essence of Operation ''Matador'' was that Allied forces would advance into Thailand and fight the Japanese there. However, the plan relied upon force levels not available to Brooke-Popham and involved violating the neutrality of Thailand, with whom a non-aggression pact had been signed the previous year.

Concern regarding the situation prompted the government in London to send Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian.

First elected to Parliament in 19 ...

as a special cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

envoy. Cooper's arrival in September 1941, did not help to maintain Brooke-Popham's authority in a difficult situation.

On 22 November, with the Japanese establishing sea and air bases in southern Indo-China

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

, Brooke-Popham urged London that Operation ''Matador'' should be put into effect, granting him permission to advance into southern Thailand. Brooke-Popham did eventually receive permission on 5 December although many conditions were attached. The plan was reworked to take account of the limited forces available and on 8 December the war with Japan began. Two days before the attack on Malaya, Hudsons of No.1 Squadron (RAAF) spotted the Japanese invasion fleet but, given uncertainty about the ships' destination and instructions to avoid offensive operations until attacks were made against friendly territory, Brooke-Popham did not allow the convoy to be bombed.Gillison, ''Royal Australian Air Force'', pp. 200–201Shores et al., ''Bloody Shambles Volume One'', pp. 74–75

Although it had been agreed in London that Brooke-Popham should be replaced as commander-in-chief on 1 November 1941, the change was not made because of the critical situation. However, with the war with Japan now unfolding, many believed that Brooke-Popham was near to a nervous collapse. The cabinet envoy Duff Cooper urged his replacement and London agreed. On 27 December, at the height of the battle for Malaya, Brooke-Popham handed over command to Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Pownall.

Brooke-Popham's return to Britain was closely followed by the fall of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire o ...

on 15 February 1942. Inevitably, Brooke-Popham was associated with the collapse and he was publicly attacked by some in Britain as the man chiefly responsible for the defeat.

Later war years

In May 1942, Brooke-Popham retired from active service in the RAF for the second time. His reputation severely damaged by the events in the Far East, he nevertheless continued to serve where he could. At some stage in 1942, Brooke-Popham became Inspector-General of theAir Training Corps

The Air Training Corps (ATC) is a British volunteer-military youth organisation. They are sponsored by the Ministry of Defence and the Royal Air Force. The majority of staff are volunteers, and some are paid for full-time work – including C ...

, a position he held until 1945. From 1944 to 1946, he served as President of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes

The Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI ) is a company created by the British government on 9 December 1920 to run recreational establishments needed by the British Armed Forces, and to sell goods to servicemen and their families. It runs ...

Council.

Later years

After Brooke-Popham relinquished his role as President of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes Council, he lived in retirement. Brooke-Popham died in the hospital at RAF Halton inBuckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

on 20 October 1953. His funeral took place at St. Edburg's Church in Bicester

Bicester ( ) is a historical market towngarden town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Cherwell (district), Cherwell district of northeastern Oxfordshire in Southern England that also comprises an Eco-towns, eco town at North Wes ...

and he was buried privately in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

.Flight International, 30 October 1953

Papers

Papers relating to Brooke-Popham's service are held in theLiddell Hart Centre for Military Archives

The Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives (LHCMA) at King's College London was set up in 1964. The Centre holds the private papers of over 700 senior British defence personnel who held office since 1900. Individual collections range in size f ...

at King's College London.''Research Guide Far East''Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King's College London, 2005. p. 2.

Footnotes and references

Further reading

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – Sir (Henry) Robert Moore Brooke-Popham

(requires login) , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooke-Popham, Robert 1878 births 1953 deaths People from Mid Suffolk District Knights Bachelor Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst People educated at Haileybury and Imperial Service College Colonial governors and administrators of Kenya British Army personnel of the Second Boer War Military of Singapore under British rule Royal Flying Corps officers British Army generals of World War I Royal Air Force generals of World War I Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Knights of the Order of St John Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Collections of the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Burials in Somerset Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry officers Military personnel from Suffolk