British Guiana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland

The English made at least two unsuccessful attempts in the 17th century to colonise the lands that would later be known as British Guiana. By that time, the Dutch had established two colonies in the area: Essequibo, administered by the

The English made at least two unsuccessful attempts in the 17th century to colonise the lands that would later be known as British Guiana. By that time, the Dutch had established two colonies in the area: Essequibo, administered by the

In the 1880s gold and diamond deposits were discovered in British Guiana, including what was thought to be the world's largest diamond in 1922. They did not generate significant revenue.

In the 1880s gold and diamond deposits were discovered in British Guiana, including what was thought to be the world's largest diamond in 1922. They did not generate significant revenue.

British Guiana is famous among

British Guiana is famous among

online

*De Barros, Juanita. "Sanitation and Civilization in Georgetown, British Guiana." ''Caribbean quarterly'' 49.4 (2003): 65-86. *Draper, Nicholas. "The rise of a new planter class? Some countercurrents from British Guiana and Trinidad, 1807–33." ''Atlantic Studies'' 9.1 (2012): 65-83. * Fraser, Cary. ''Ambivalent Anti-Colonialism: The United States and the Genesis of West Indian Independence, 1940-64'' (Westport, 1994) *Fraser, Cary. "The 'New Frontier' of Empire in the Caribbean: The Transfer of Power in British Guiana, 1961–1964." ''International History Review'' 22.3 (2000): 583-610

online

*Green, William A. “Caribbean Historiography, 1600-1900: The Recent Tide.” ''Journal of Interdisciplinary History'' 7#3 1977, pp. 509–530

online

*Khanam, Bibi H., and Raymond S. Chickrie. "170th anniversary of the arrival of the first hindustani muslims from India to British Guiana." ''Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs'' 29.2 (2009): 195-222. *Kumar, Mukesh. “Malaria and Mortality Among Indentured Indians: A Study of Housing, Sanitation, and Health in British Guiana (1900-1939).” ''Proceedings of the Indian History Congress,'' vol. 74, 2013, pp. 746–757

online

*Laurence, Keith Ormiston. ''A question of labour: indentured immigration into Trinidad and British Guiana, 1875-1917'' (St. Martin's Press, 1994). * Lutz, Jessie G. “Chinese Emigrants, Indentured Workers, and Christianity In The West Indies, British Guiana And Hawaii.” ''Caribbean Studies'' 37#2, 2009, pp. 133–154

online

*Munro, Arlene. "British Guiana's Contribution to the British War Effort, 1939-1945." ''Journal of Caribbean History'' 39.2 (2005): 249-262. *Palmer, Colin A. ''Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power: British Guiana's Struggle for Independence'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2010); online at JSTOR *Rabe, Stephen G. ''U.S. intervention in British Guiana: A cold war story'' (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2006). *Roopnarine, Lomarsh. "A critique of East Indian indentured historiography in the Caribbean." ''Labor History'' 55.3 (2014): 389-401. *Roopnarine, Lomarsh. "Indian migration during indentured servitude in British Guiana and Trinidad, 1850–1920." ''Labor History'' 52.2 (2011): 173-191. *Schoenrich, Otto. "The Venezuela-British Guiana Boundary Dispute." ''American Journal of International Law'' 43.3 (1949): 523-530

online

*Spinner, Thomas J. ''A political and social history of Guyana, 1945-1983'' (Westview Press, 1984). *Will, Henry Austin. ''Constitutional change in the British West Indies, 1880-1903: with special reference to Jamaica, British Guiana, and Trinidad'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970).

online

{{Authority control Guiana, British States and territories established in 1814 Former colonies in South America Guiana 1831 establishments in South America 1966 disestablishments in British Guiana States and territories disestablished in 1966 1831 establishments in the British Empire

British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

. It was located on the northern coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana

Guyana, officially the Co-operative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern coast of South America, part of the historic British West Indies. entry "Guyana" Georgetown, Guyana, Georgetown is the capital of Guyana and is also the co ...

.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guiana were Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

, an English explorer, and his crew.

Raleigh published a book entitled '' The Discovery of Guiana'', but this mainly relates to the Guayana region of Venezuela.

The Dutch were the first Europeans to settle there, starting in the early 17th century. They founded the colonies of Essequibo and Berbice

Berbice () is a region along the Berbice River in Guyana, which was between 1627 and 1792 a colony of the Dutch West India Company and between 1792 and 1815 a colony of the Dutch state. After having been ceded to the United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

, adding Demerara

Demerara (; , ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state from 1792 unti ...

in the mid-18th century.

In 1796, Great Britain took over these three colonies during hostilities with the French, who had occupied the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. Britain returned control of the territory to the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic (; ) was the Succession of states, successor state to the Dutch Republic, Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 after the Batavian Revolution and ended on 5 June 1806, with the acce ...

in 1802, but captured the colonies a year later during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. The Netherlands officially ceded the colonies to the United Kingdom in 1815.

The British consolidated the territories into a single colony in 1831. The colony's capital was at Georgetown (known as Stabroek prior to 1812).

Since the late 19th century, the economy has become more diversified but has still relied on resource exploitation

The exploitation of natural resources describes using natural resources, often non-renewable or limited, for economic growth or development. Environmental degradation, human insecurity, and social conflict frequently accompany natural resource ex ...

. Guyana became independent of the United Kingdom on 26 May 1966.

Establishment

The English made at least two unsuccessful attempts in the 17th century to colonise the lands that would later be known as British Guiana. By that time, the Dutch had established two colonies in the area: Essequibo, administered by the

The English made at least two unsuccessful attempts in the 17th century to colonise the lands that would later be known as British Guiana. By that time, the Dutch had established two colonies in the area: Essequibo, administered by the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company () was a Dutch chartered company that was founded in 1621 and went defunct in 1792. Among its founders were Reynier Pauw, Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), and Jessé de Forest (1576–1624). On 3 June 1621, it was gra ...

, and Berbice

Berbice () is a region along the Berbice River in Guyana, which was between 1627 and 1792 a colony of the Dutch West India Company and between 1792 and 1815 a colony of the Dutch state. After having been ceded to the United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

, administered by the Berbice Association. The Dutch West India Company founded a third colony, Demerara

Demerara (; , ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state from 1792 unti ...

, in the mid-18th century.

During the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

of the late 18th century, when the Netherlands were occupied by the French, and Great Britain and France were at war, Britain took over the colony in 1796. A British expeditionary force was dispatched from its colony of Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

to seize the colonies from the French-dominated Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic (; ) was the Succession of states, successor state to the Dutch Republic, Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 after the Batavian Revolution and ended on 5 June 1806, with the acce ...

. The colonies surrendered without a struggle. Initially very little changed, as the British agreed to allow the long-established laws of the colonies to remain in force.

In 1802 Britain returned the colonies to the Batavian Republic under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France, the Spanish Empire, and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it set t ...

. But, after resuming hostilities with France in the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

in 1803, Britain seized the colonies again less than a year later. The Netherlands officially ceded the three colonies to the United Kingdom in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

The UK continued separate administration of the individual colonies until 1822, when the administration of Essequibo and Demerara was combined. In 1831, the administration Essequibo-Demerara and Berbice was combined, and the united colony became known as British Guiana. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

established NAF British Guiana and NAF Paramaribo in British Guiana.

Economy and politics

The economy was based on cultivation and processing ofsugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fib ...

as a commodity crop, dependent on extensive labor by enslaved workers of mostly sub-Saharan African

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

descent. Although the UK and the United States abolished the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

in 1807, the domestic slave trade flourished until Britain emancipated all the enslaved in its colonies in the 1830s. The wealth they generated had largely flowed to a group of absentee slave owners living in Britain, especially in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

and Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

.

The economy of British Guiana was completely based on sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fib ...

production until the 1880s, when falling cane sugar prices stimulated a shift toward rice farming, mining and forestry. But the production of sugarcane remained a significant part of the economy (in 1959 sugar still accounted for nearly 50% of exports). Under the Dutch, settlement and economic activity was concentrated around sugarcane plantations lying inland from the coast.

Under the British, cane planting expanded to richer coastal lands, with greater coastline protection. Until the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, sugar planters depended almost exclusively on slave labour to produce sugar. Georgetown was the site of a significant slave rebellion in 1823.

In the 1880s gold and diamond deposits were discovered in British Guiana, including what was thought to be the world's largest diamond in 1922. They did not generate significant revenue.

In the 1880s gold and diamond deposits were discovered in British Guiana, including what was thought to be the world's largest diamond in 1922. They did not generate significant revenue.

Bauxite

Bauxite () is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)), and diaspore (α-AlO(OH) ...

deposits proved more promising and would remain an important part of the economy. The colony did not develop any significant manufacturing industry, other than sugar factories, rice mills, sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

s, and certain small-scale industries (including a brewery, a soap factory, a biscuit factory and an oxygen-acetylene plant, among others).

The London-based Booker Group

Booker Group Limited is a British wholesale distributor, and subsidiary of Tesco plc.

In January 2017, it was announced that the British multinational supermarket retailer Tesco had agreed to purchase the company for £3.7 billion. It was con ...

of companies (Booker Brothers, McConnell & Co., Ltd) dominated the economy of British Guiana. The Bookers had owned sugar plantations in the colony since the early 19th century; by the end of the century they owned a majority of them. By 1950 they owned all but three. With the increasing success and wealth of the Booker Group, they expanded internationally and diversified by investing in rum, pharmaceuticals, publishing, advertising, retail stores, timber, and petroleum, among other industries. The Booker Group became the largest employer in the colony, leading some to refer to it as "Booker's Guiana".

Indentured workers were recruited from India from 1850 to 1920, and were largely locked in place. A minority achieved mobility. Some secretly fled; others waited until their contracts expired. Indian migration within the colonies involved three phases: desertion from the plantations; movement settlements and later to urban areas; and intra-regional migration from one Caribbean island to another. The traditional rigid Indian caste system

A caste is a fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (endogamy), foll ...

largely collapsed in the colonies.

Guianese served in all British forces during the Second World War, and enjoyed veterans' benefits afterwards. The colony made a small but important financial contribution to the war effort. It also served as a refuge for Jews displaced from continental Europe, where the Nazis and Fascists worked to destroy them in the Holocaust.

Railways

British colonists built the first railway system in British Guiana: of , from Georgetown to Rosignol, and of line between Vreeden Hoop and Parika; it opened in 1848. Several narrow-gauge lines were built to serve the sugar industry and others were built to serve the later bauxite and other mines. In 1948, when the railway in Bermuda was closed down, the locomotives, rolling stock, track, sleepers and virtually all the associated paraphernalia of a railway were shipped to British Guiana to renovate the aged system. The lines ceased to operate in 1972. The large Central Station is still standing in Georgetown. Some of the inland mines still operate narrow-gauge lines.Administration

The British long continued the forms of Dutch colonial government in British Guiana. A Court of Policy exercised bothlegislative

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers ...

and executive functions under the direction of the colonial Governor (which existed from 1831 to 1966). A group known as the Financial Representatives sat with the Court of Policy in a Combined Court to set tax policies. A majority of the members of the Courts was appointed by the Governor; the rest were selected by a College of Kiezers (Electors). The Kiezers were elected, with the restrictive franchise based on property holdings and limited to the larger landowners of the colony. They held this office for life, or during residence of the colony. The Courts were dominated in the early centuries by the sugar planters and their representatives.

In 1891 the College of Kiezers was abolished in favour of direct election of the elective membership of the Courts. Membership of the Court of Policy became half elected and half appointed, and all of the Financial Representatives became elective positions. The executive functions of the Court of Policy were transferred to a new Executive Council under the control of the Governor. Property qualifications were significantly relaxed for voters and for candidates to the Courts.

In 1928 the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

abolished the Dutch-influenced constitution and replaced it with a Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

constitution. A Legislative Council with an appointed majority was established, and the administrative powers of the Governor were strengthened. These constitutional changes were not popular among the Guyanese, who viewed them as a step backward. The franchise was extended to women.

In 1938 the West India Royal Commission ("The Moyne Commission") was appointed to investigate the economic and social condition of all the British colonies in the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

region after a number of civil and labour disturbances. Among other changes, the Commission recommended some constitutional reforms. As a result, in 1943 a majority of the Legislative Council seats became elective, the property qualifications for voters and for candidates for the Council were lowered, and the bar on women and clergy serving on the Council was abolished. The Governor retained control of the Executive Council, which had the power to veto or pass laws against the wishes of the Legislative Council.

The next round of constitutional reforms came in 1953. A bicameral

legislature, consisting of a lower House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies as the colony gained more internal responsible g ...

and an upper State Council, was established. The voting membership of the House of Assembly was entirely elective. The membership of the State Council was appointed by the Governor and the House of Assembly and possessed limited revisionary powers. A Court of Policy became the executive body, consisting of the Governor and other colonial officials. Universal adult suffrage was instituted, and the property qualifications for office abolished.

The election of 27 April 1953 under the new system provoked a serious constitutional crisis. The People's Progressive Party (PPP) won 18 of the 24 seats in the House of Assembly. This result alarmed the British Government, which was surprised by the strong showing of the PPP. It considered the PPP as too friendly with communist organisations.

As a result of its fears of communist influence in the colony, the British Government suspended the constitution, declared a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

, and militarily occupied British Guiana on 9 October 1953. Under the direction of the British Colonial Office, the Governor assumed direct rule of the colony under an Interim Government, which continued until 1957. On 12 August 1957, elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

were held and the PPP won nine of fourteen elective seats in a new legislature.

A constitutional convention convened in London in March 1960 reached agreement on another new legislature, to consist of an elected House of Assembly (35 seats) and a nominated Senate (13 seats). In the ensuing election of 21 August 1961, the PPP won 20 seats in the House of Assembly, entitling it as the majority party to appoint eight senators. Upon the 1961 election, British Guiana also became self-governing

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

, except as to defence and external matters. The leader of the majority party became prime minister, who then named a Council of Ministers, replacing the former Executive Council.

From 1962 to 1964, riots, strikes and other disturbances stemming from racial, social and economic conflicts delayed full independence for British Guiana. The leaders of the political parties reported to the British Colonial Secretary that they were unable to reach agreement on the remaining details of forming an independent government. The British Colonial Office intervened by imposing its own independence plan, in part requiring another election under a new proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (Political party, political parties) amon ...

system. Britain expected that this system would reduce the number of seats won by the PPP and prevent it from obtaining a majority.

The December 1964 elections for the new legislature gave the PPP 45.8% (24 seats), the People's National Congress (PNC) 40.5% (22 seats) and the United Force (UF) 12.4% (7 seats). The UF agreed to form a coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

with the PNC, and accordingly, the PNC leader became the new prime minister. In November 1965 an independence conference in London quickly reached agreement on an independent constitution; it set the date for independence as 26 May 1966. On that date, at 12 midnight, British Guiana became the new nation of Guyana

Guyana, officially the Co-operative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern coast of South America, part of the historic British West Indies. entry "Guyana" Georgetown, Guyana, Georgetown is the capital of Guyana and is also the co ...

.

Territorial disputes

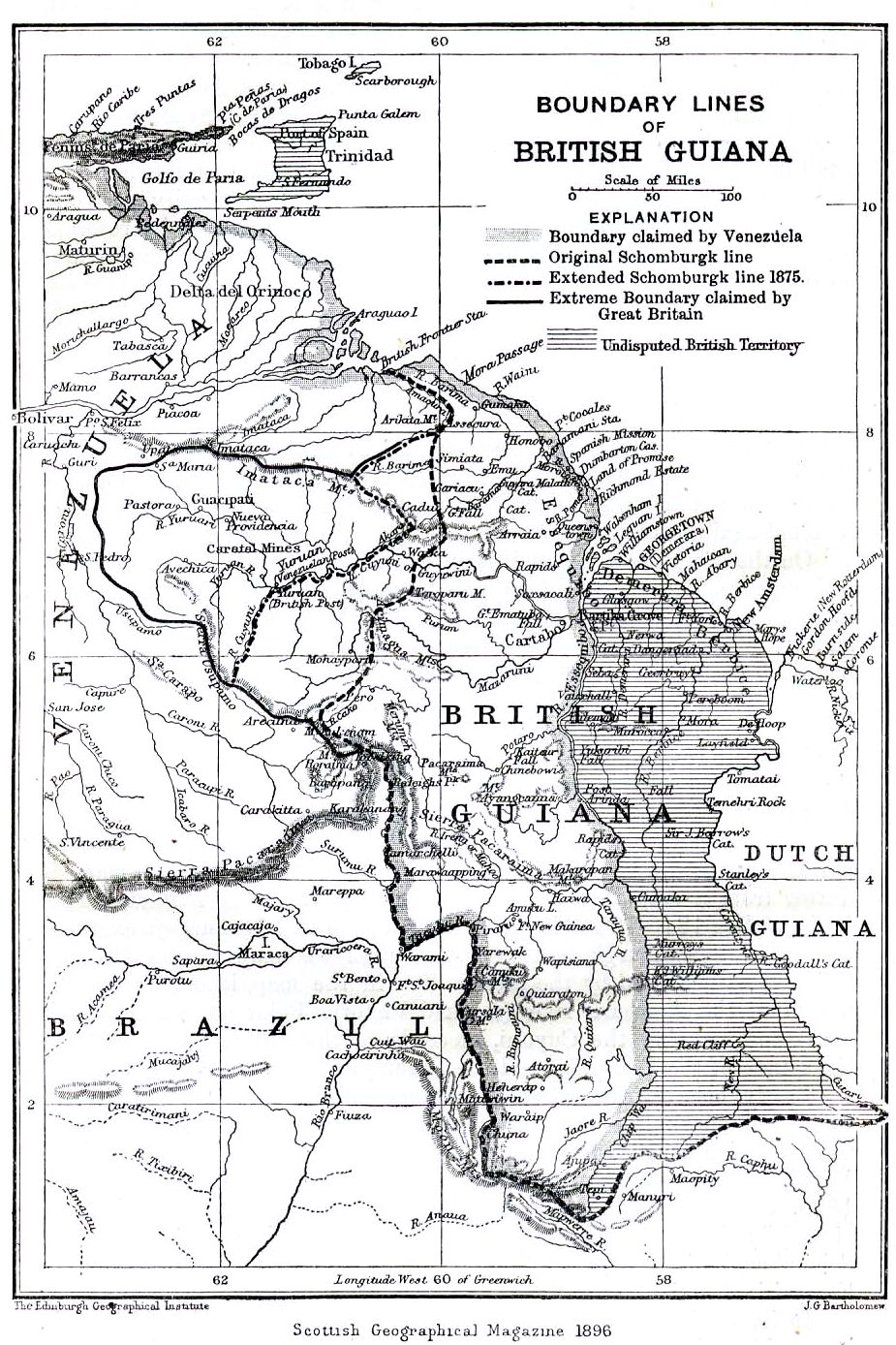

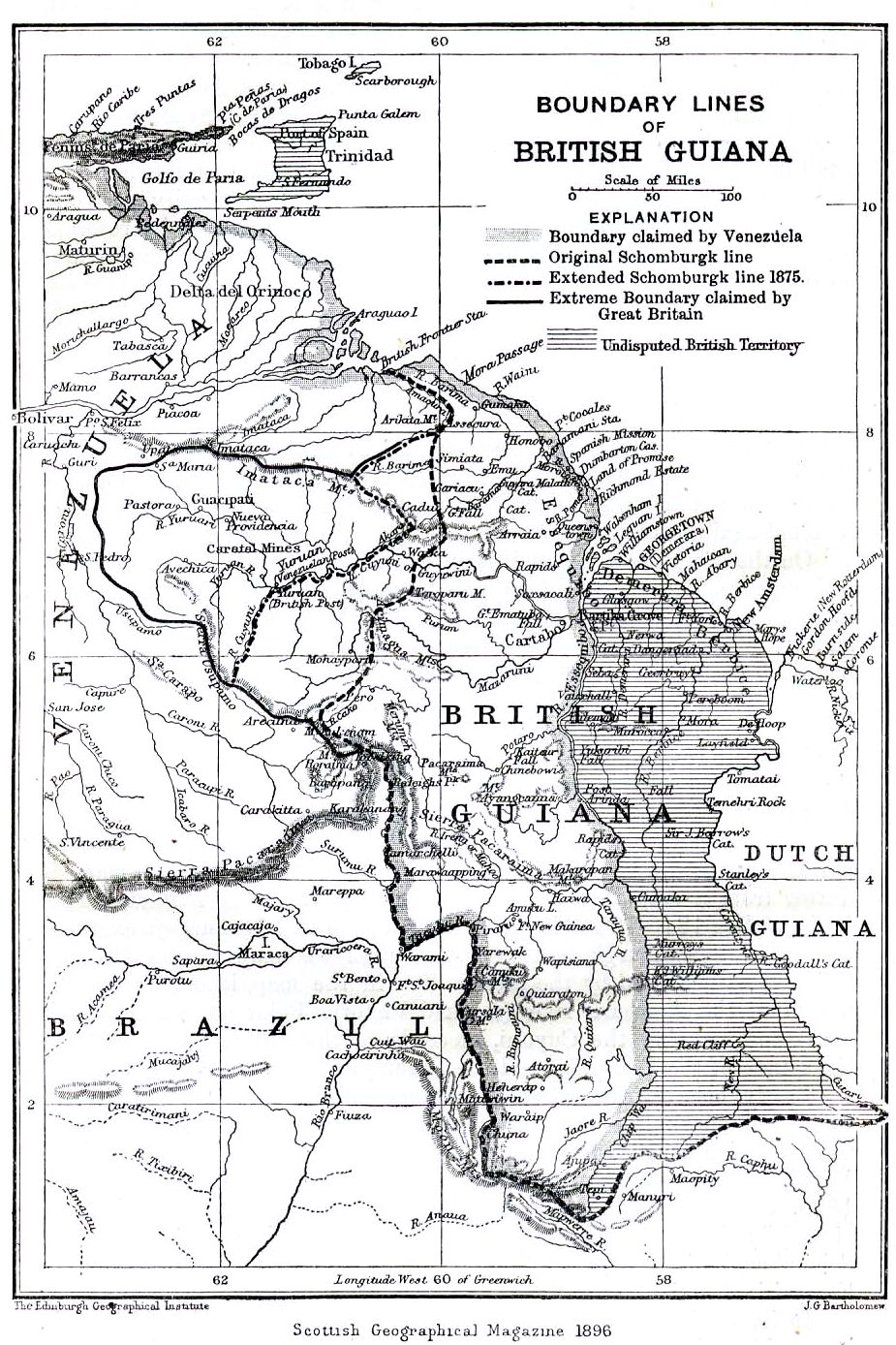

Western boundary with Venezuela

In 1840, the British Government assigned the German-born explorer Robert Hermann Schomburgk to survey and mark out the western boundary of British Guiana with newly independentVenezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

. Venezuela did not accept the Schomburgk Line

The Schomburgk Line is the name given to a surveying, survey line that figured in a 19th-century territorial dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana. The line was named after German-born English explorer and naturalist Robert Hermann Schombu ...

, which placed the entire Cuyuni River basin within the colony. Venezuela claimed all lands west of the Essequibo River

The Essequibo River (; originally called by Alonso de Ojeda; ) is the largest river in Guyana, and the largest river between the Orinoco and Amazon River, Amazon. Rising in the Acarai Mountains near the Brazil–Guyana border, the Essequibo flows ...

as its territory (see map in this section).

The dispute continued on and off for half a century, culminating in the Venezuela Crisis of 1895, in which Venezuela sought to use the United States' Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

to win support for its position. US President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

used diplomatic pressure to get the British to agree to arbitration of the issue, ultimately agreeing terms for the arbitration that suited Britain. An arbitration tribunal

An arbitral tribunal or arbitration tribunal, also arbitration commission, arbitration committee or arbitration council is a panel of adjudicators which is convened and sits to resolve a dispute by way of arbitration. The tribunal may consist o ...

convened in Paris in 1898, and issued its award

An award, sometimes called a distinction, is given to a recipient as a token of recognition of excellence in a certain field. When the token is a medal, ribbon or other item designed for wearing, it is known as a decoration.

An award may be d ...

in 1899. The tribunal awarded about 94% of the disputed territory to British Guiana. A commission surveyed a new border according to the award, and the parties accepted the boundary in 1905.

There the matter rested until 1962, when Venezuela renewed its 19th-century claim, alleging that the arbitral award was invalid. After his death, Severo Mallet-Prevost, legal counsel for Venezuela and a named partner in the New York law firm Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle published a letter alleging that the judges on the tribunal acted improperly as a result of a back-room deal between Russia and Great Britain. The British Government rejected this claim, asserting the validity of the 1899 award. The British Guiana Government, then under the leadership of the PPP, also strongly rejected this claim. Efforts by all parties to resolve the matter on the eve of Guyana's independence in 1966 failed; as of today, the dispute remains unresolved.

Eastern boundary with Suriname

Robert Schomburgk's 1840 commission also included a survey of the colony's eastern boundary with the Dutch colony of Surinam, now the independent nation of Suriname. The 1899 arbitration award settling the British Guiana–Venezuela border made reference to the border with Suriname as continuing to the source of theCourantyne River

The Courantyne River ( ), also known as Corentyne and Corantijn (), is a river in northern South America in Suriname and Guyana. It is the longest List of rivers of Suriname, river in the country and creates the border between Suriname and the Eas ...

, which it named as the Kutari River. The Netherlands raised a diplomatic protest, claiming that the New River, and not the Kutari, was to be regarded as the source of the Courantyne and the boundary. The British government in 1900 replied that the issue was already settled by the longstanding acceptance of the Kutari as the boundary.

In 1962, the Kingdom of the Netherlands

The Kingdom of the Netherlands (, ;, , ), commonly known simply as the Netherlands, is a sovereign state consisting of a collection of constituent territories united under the monarch of the Netherlands, who functions as head of state. The re ...

, on behalf of its then- constituent country of Suriname, finally made formal claim to the "New River Triangle

The Tigri Area () or New River Triangle is a forested area in the East Berbice-Corentyne region of Guyana that has been disputed by Suriname since the 19th century. In Suriname, it is seen as an integral part of the Coeroeni, Coeroeni Resort l ...

", the triangular-shaped region between the New and Kutari rivers that was in dispute. The then Surinamese colonial government and, after 1975, the independent Surinamese government, maintained the Dutch position, while the British Guiana Government, and later the independent Guyanese government, maintained the British position.

Stamps and postal history of British Guiana

British Guiana is famous among

British Guiana is famous among philatelists

Philately (; ) is the study of postage stamps and postal history. It also refers to the collection and appreciation of stamps and other philatelic products. While closely associated with stamp collecting and the study of postage, it is possible ...

for its early postage stamps, which were first issued in 1850. These stamps include some of the rarest, most expensive stamps in the world, such as the unique British Guiana 1c magenta from 1856, which was sold in 2014 for US$9.5 million.

See also

* Economy of Guyana * Geography of Guyana * Guyanese British * History of Guyana *Politics of Guyana

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of status or resources.

The branch of social science that studies poli ...

* Robert Hermann Schomburgk

* Charles Waterton

References

Further reading

*De Barros, Juanita. "'Spreading Sanitary Enlightenment': Race, Identity, and the Emergence of a Creole Medical Profession in British Guiana." ''Journal of British Studies'' 42.4 (2003): 483-501online

*De Barros, Juanita. "Sanitation and Civilization in Georgetown, British Guiana." ''Caribbean quarterly'' 49.4 (2003): 65-86. *Draper, Nicholas. "The rise of a new planter class? Some countercurrents from British Guiana and Trinidad, 1807–33." ''Atlantic Studies'' 9.1 (2012): 65-83. * Fraser, Cary. ''Ambivalent Anti-Colonialism: The United States and the Genesis of West Indian Independence, 1940-64'' (Westport, 1994) *Fraser, Cary. "The 'New Frontier' of Empire in the Caribbean: The Transfer of Power in British Guiana, 1961–1964." ''International History Review'' 22.3 (2000): 583-610

online

*Green, William A. “Caribbean Historiography, 1600-1900: The Recent Tide.” ''Journal of Interdisciplinary History'' 7#3 1977, pp. 509–530

online

*Khanam, Bibi H., and Raymond S. Chickrie. "170th anniversary of the arrival of the first hindustani muslims from India to British Guiana." ''Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs'' 29.2 (2009): 195-222. *Kumar, Mukesh. “Malaria and Mortality Among Indentured Indians: A Study of Housing, Sanitation, and Health in British Guiana (1900-1939).” ''Proceedings of the Indian History Congress,'' vol. 74, 2013, pp. 746–757

online

*Laurence, Keith Ormiston. ''A question of labour: indentured immigration into Trinidad and British Guiana, 1875-1917'' (St. Martin's Press, 1994). * Lutz, Jessie G. “Chinese Emigrants, Indentured Workers, and Christianity In The West Indies, British Guiana And Hawaii.” ''Caribbean Studies'' 37#2, 2009, pp. 133–154

online

*Munro, Arlene. "British Guiana's Contribution to the British War Effort, 1939-1945." ''Journal of Caribbean History'' 39.2 (2005): 249-262. *Palmer, Colin A. ''Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power: British Guiana's Struggle for Independence'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2010); online at JSTOR *Rabe, Stephen G. ''U.S. intervention in British Guiana: A cold war story'' (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2006). *Roopnarine, Lomarsh. "A critique of East Indian indentured historiography in the Caribbean." ''Labor History'' 55.3 (2014): 389-401. *Roopnarine, Lomarsh. "Indian migration during indentured servitude in British Guiana and Trinidad, 1850–1920." ''Labor History'' 52.2 (2011): 173-191. *Schoenrich, Otto. "The Venezuela-British Guiana Boundary Dispute." ''American Journal of International Law'' 43.3 (1949): 523-530

online

*Spinner, Thomas J. ''A political and social history of Guyana, 1945-1983'' (Westview Press, 1984). *Will, Henry Austin. ''Constitutional change in the British West Indies, 1880-1903: with special reference to Jamaica, British Guiana, and Trinidad'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970).

Primary sources

*Perkins, Harry Innes. ''Notes on British Guiana and its gold industry'' (Waterlow & Sons, 1895online

{{Authority control Guiana, British States and territories established in 1814 Former colonies in South America Guiana 1831 establishments in South America 1966 disestablishments in British Guiana States and territories disestablished in 1966 1831 establishments in the British Empire