Brenner v. Manson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Brenner v. Manson'', 383 U.S. 519 (1966), was a decision of the

Justice

Justice

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in which the Court held that a novel process for making a known steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

did not satisfy the utility requirement, because the patent applicants did not show that the steroid served any practical function. The Court ruled that "a process patent in the chemical field, which has not been developed and pointed to the degree of specific utility, creates a monopoly of knowledge which should be granted only if clearly commanded by the statute." Practical or specific utility, so that a "specific benefit exists in currently available form" is thus the requirement for a claimed invention to qualify for a patent.383 U.S. at 534-35.

The case is known for the statement "a patent is not a hunting license."

Appellate jurisdiction issue

The ''Manson'' case is the first in which the Court granted a writ of ''certiorari

In law, ''certiorari'' is a court process to seek judicial review of a decision of a lower court or government agency. ''Certiorari'' comes from the name of an English prerogative writ, issued by a superior court to direct that the record of ...

'' in an appeal of a patent office rejection of a patent application. For many years there had been uncertainty whether the United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals

The United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA) was a United States federal court which existed from 1909 to 1982 and had jurisdiction over certain types of civil disputes.

History

The CCPA began as the United States Court of Customs ...

(CCPA) was an Article III court, and thus one as to which the Supreme Court had ''certiorari'' jurisdiction.

For many years, almost until the eve of the ''Manson'' case, the Solicitor General had opposed petitions for ''certiorari'' by disappointed patent applicants on the basis that the CCPA was an Article I court to which the Supreme Court's ''certiorari'' jurisdiction did not extend. In ''Lurk v. United States'', however, the Court held that judges of the CCPA (as well as those of the Court of Claims) were Article III judges. In the ''Manson'' case the Court expressly held, unanimously, that ''certiorari'' was available to review CCPA decisions.

This paved the way for the US Government to seek review in the Supreme Court of judgments of the CCPA (and its successor the Federal Circuit) reversing denials of patent applications, which it did beginning with ''Manson''.

Substantive patent law issue

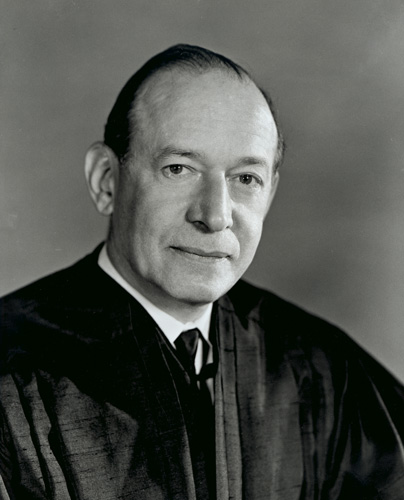

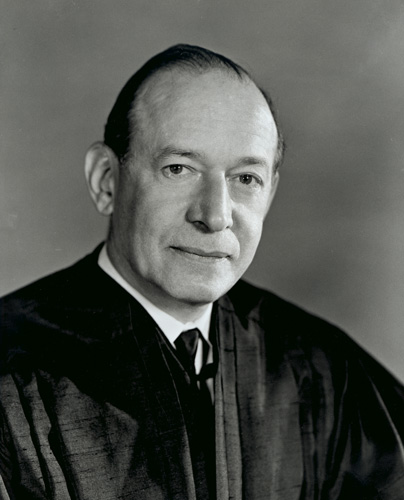

Justice

Justice Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from Rhod ...

delivered the unanimous opinion of the Court on the jurisdictional issue in this case and the 7-2 opinion of the Court on the issue of utility. Justice John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him ...

, joined by Justice William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often c ...

, dissented on the utility issue.

Majority opinion

The substantive patent law issue in the case was the degree of specific utility a claimed invention must have in order to qualify for patenting. Andrew Manson applied for a patent on a novel process for making a form ofdihydrotestosterone

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT, 5α-dihydrotestosterone, 5α-DHT, androstanolone or stanolone) is an endogenous androgen sex steroid and hormone. The enzyme 5α-reductase catalyzes the formation of DHT from testosterone in certain tissues includi ...

, a known steroid chemical. A specific use for the product was not known or disclosed by Manson, although it was hypothesized that it could be screened for possible anti-cancer utility. Other steroids of similar chemical structure were known to inhibit tumors in mice. The Patent Office took the position that a process for making a known product could be patented only if the product had a known utility, while Manson argued, and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals subsequently agreed, that it was sufficient for the process to be useful in making the product regardless of whether the product itself had any particular utility. The Patent Office refused to allow Manson to proceed. He appealed, and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals reversed the Patent Office, saying that "where a claimed process produces a known product, it is not necessary to show utility for the product" so long as the product "is not alleged to be detrimental to the public interest." The Office then sought review in the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court began by considering whether the fact that a closely related chemical had displayed anti-tumor activity in mice sufficed to satisfy the requirement in 35 U.S.C. § 101 that the subject matter of a patent must be "useful."

The Court said it would not overturn the Office's finding that it did not follow from the mice data that the claimed process was useful, because whether the steroid product yielded by Manson's process would have similar tumor-inhibiting characteristics could not be assumed without proof, given the unpredictability of compounds in the steroid field. Nor was that the invention was not "harmful to society" sufficient. "There are, after all, many things in this world which may not be considered "useful" but which, nevertheless are totally without a capacity for harm."

Manson argued that allowing such claims as his would encourage disclosure, discourage secrecy, and promote efforts to make technological advances. The Court replied that a ’more compelling consideration" was that the monopoly so granted would discourage inventive activity by others:

process patent in the chemical field, which has not been developed and pointed to the degree of specific utility, creates a monopoly of knowledge which should be granted only if clearly commanded by the statute. Until the process claim has been reduced to production of a product shown to be useful, the metes and bounds of that monopoly are not capable of precise delineation. It may engross a vast, unknown, and perhaps unknowable area. Such a patent may confer power to block off whole areas of scientific development, without compensating benefit to the public. The basic ''quid pro quo'' contemplated by the Constitution and the Congress for granting a patent monopoly is the benefit derived by the public from an invention with substantial utility. Unless and until a process is refined and developed to this point—where specific benefit exists in currently available form—there is insufficient justification for permitting an applicant to engross what may prove to be a broad field.

Dissent

In dissent, Justice Harlan argued that the result of the ruling might be to retard chemical progress:What I find most troubling about the result reached by the Court is the impact it may have on chemical research. Chemistry is a highly interrelated field, and a tangible benefit for society may be the outcome of a number of different discoveries, one discovery building upon the next. To encourage one chemist or research facility to invent and disseminate new processes and products may be vital to progress, although the product or process be without "utility" as the Court defines the term, because that discovery permits someone else to take a further but perhaps less difficult step leading to a commercially useful item. In my view, our awareness in this age of the importance of achieving and publicizing basic research should lead this Court to resolve uncertainties in its favor, and uphold the respondent's position in this case.

Follow-up

Two relevant cases (In re Kirk

IN, In or in may refer to:

Places

* India (country code IN)

* Indiana, United States (postal code IN)

* Ingolstadt, Germany (license plate code IN)

* In, Russia, a town in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

Businesses and organizations

* Indepen ...

and In re Joly

IN, In or in may refer to:

Places

* India (country code IN)

* Indiana, United States (postal code IN)

* Ingolstadt, Germany (license plate code IN)

* In, Russia, a town in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

Businesses and organizations

* Indepen ...

)In re Joly, 376 F.2d 906 (C.C.P.A. 1967) were decided by the court on the same day. and applied the Brenner standard.

References

External links

* {{caselaw source , case = ''Brenner v. Manson'', {{ussc, 383, 519, 1966, el=no , courtlistener =https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/107190/brenner-v-manson/ , findlaw = https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/383/519.html , googlescholar = https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=4743287006156005385 , justia =https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/383/519/case.html , loc =http://cdn.loc.gov/service/ll/usrep/usrep383/usrep383519/usrep383519.pdf , oyez =https://www.oyez.org/cases/1965/58 United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court cases of the Warren Court United States patent case law 1966 in United States case law