Brabant Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Brabant Revolution or Brabantine Revolution (french: Révolution brabançonne, nl, Brabantse Omwenteling), sometimes referred to as the Belgian Revolution of 1789–1790 in older writing, was an armed insurrection that occurred in the

The

The

Propelled by his belief in the Enlightenment, soon after taking power, Joseph launched a number of reforms which he hoped would make the territories he controlled more efficient and easier to govern. From 1784, Joseph launched a number of "radical and wide-ranging" reforms in the fields of economics, politics and religion aimed at institutions which he judged outdated. Some have drawn parallels between Joseph's rule in the Holy Roman Empire and that of Philip II in the Netherlands as both attempted to suborn local traditions in order to achieve more effective central rule. Like Philip, Joseph's perceived attacks on important institutions succeeded in uniting multiple divergent social classes against him.

His initial reforms were aimed at the Catholic church which, because of its allegiance to the Vatican, was viewed a potentially subversive force. Joseph's first act was the proclamation of the Edict of Tolerance of 1781–82 which abolished the privileges which Catholics enjoyed over other Christian and non-Christian minorities. As an attack on the place of the church, it was deeply unpopular among Catholics, but because the non-Catholics were a tiny minority, it did not win any real support. The Edict was condemned by Cardinal Frankenberg who insisted that religious tolerance, the relaxation of censorship and the suppression of laws against the Jansenists all constituted an attack on the Catholic Church. Later, 162 monasteries whose inhabitants led a purely contemplative life were abolished. In September 1784, marriage was made a

Propelled by his belief in the Enlightenment, soon after taking power, Joseph launched a number of reforms which he hoped would make the territories he controlled more efficient and easier to govern. From 1784, Joseph launched a number of "radical and wide-ranging" reforms in the fields of economics, politics and religion aimed at institutions which he judged outdated. Some have drawn parallels between Joseph's rule in the Holy Roman Empire and that of Philip II in the Netherlands as both attempted to suborn local traditions in order to achieve more effective central rule. Like Philip, Joseph's perceived attacks on important institutions succeeded in uniting multiple divergent social classes against him.

His initial reforms were aimed at the Catholic church which, because of its allegiance to the Vatican, was viewed a potentially subversive force. Joseph's first act was the proclamation of the Edict of Tolerance of 1781–82 which abolished the privileges which Catholics enjoyed over other Christian and non-Christian minorities. As an attack on the place of the church, it was deeply unpopular among Catholics, but because the non-Catholics were a tiny minority, it did not win any real support. The Edict was condemned by Cardinal Frankenberg who insisted that religious tolerance, the relaxation of censorship and the suppression of laws against the Jansenists all constituted an attack on the Catholic Church. Later, 162 monasteries whose inhabitants led a purely contemplative life were abolished. In September 1784, marriage was made a

Joseph's reforms were deeply unpopular within the Austrian Netherlands. The Enlightenment had made few inroads into the territory, and it was widely distrusted as a foreign phenomenon which was not compatible with traditional local values. The majority of the population, especially influenced by the Church, believed the reforms to be a threat to their own cultures and traditions which would leave them worse off. Even in pro-Enlightenment circles, the reforms caused discontent which were seen as not sufficiently radical and not far reaching enough. Popular opposition was centered on the provincial states, in particular Hainaut, Brabant and Flanders, as well as their law courts. There was a wave of critical pamphleting. In some towns, riots broke out and the militia had to be called to suppress them. The Estate of Brabant called a lawyer, Henri Van der Noot, to defend their position publicly. Van der Noot publicly accused the reforms of violating the precedents established by the Joyous Entry of 1356 which was widely regarded as a traditional

Joseph's reforms were deeply unpopular within the Austrian Netherlands. The Enlightenment had made few inroads into the territory, and it was widely distrusted as a foreign phenomenon which was not compatible with traditional local values. The majority of the population, especially influenced by the Church, believed the reforms to be a threat to their own cultures and traditions which would leave them worse off. Even in pro-Enlightenment circles, the reforms caused discontent which were seen as not sufficiently radical and not far reaching enough. Popular opposition was centered on the provincial states, in particular Hainaut, Brabant and Flanders, as well as their law courts. There was a wave of critical pamphleting. In some towns, riots broke out and the militia had to be called to suppress them. The Estate of Brabant called a lawyer, Henri Van der Noot, to defend their position publicly. Van der Noot publicly accused the reforms of violating the precedents established by the Joyous Entry of 1356 which was widely regarded as a traditional

In the aftermath of the suppression of the Small Revolution, opposition began to consolidate into more organised resistance. Fearing for his safety, Van der Noot, the organiser of the disruption of 1787, went into exile in the Dutch Republic where he tried to lobby support from William V. Van der Noot attempted to persuade William to support the overthrow of the Austrian regime and install his son, Frederick, as ''

In the aftermath of the suppression of the Small Revolution, opposition began to consolidate into more organised resistance. Fearing for his safety, Van der Noot, the organiser of the disruption of 1787, went into exile in the Dutch Republic where he tried to lobby support from William V. Van der Noot attempted to persuade William to support the overthrow of the Austrian regime and install his son, Frederick, as ''

The Brabant Revolution broke out on 24 October 1789 when the ''émigré'' patriot army under Van der Mersch crossed over the Dutch border into the Austrian Netherlands. The army, which numbered 2,800 men, crossed into the Kempen region south of Breda. The army arrived in the town of Hoogstraten where a specially prepared document, the Manifesto of the People of Brabant (''Manifeste du peuple brabançon''), was read in the city hall. The document denounced Joseph II's rule and declared that he no longer held legitimacy. The text of the speech itself was an embellished version of the 1581 declaration (the ''Verlatinge'') by the Dutch States-General denouncing Philip II's rule in the Netherlands.

On 27 October, the patriot army clashed with a much-larger Austrian force at the nearby town of Turnhout. The ensuing battle was a triumph for the outnumbered rebels and the Austrians suffered a "shameful defeat". The rebel triumph broke the back of the Austrian forces in Belgium and many local soldiers within the Austrian force deserted to the patriot cause. Swelled by new recruits and supported by the population, the patriot army advanced rapidly into Flanders. On 16 November, Flander's major city,

The Brabant Revolution broke out on 24 October 1789 when the ''émigré'' patriot army under Van der Mersch crossed over the Dutch border into the Austrian Netherlands. The army, which numbered 2,800 men, crossed into the Kempen region south of Breda. The army arrived in the town of Hoogstraten where a specially prepared document, the Manifesto of the People of Brabant (''Manifeste du peuple brabançon''), was read in the city hall. The document denounced Joseph II's rule and declared that he no longer held legitimacy. The text of the speech itself was an embellished version of the 1581 declaration (the ''Verlatinge'') by the Dutch States-General denouncing Philip II's rule in the Netherlands.

On 27 October, the patriot army clashed with a much-larger Austrian force at the nearby town of Turnhout. The ensuing battle was a triumph for the outnumbered rebels and the Austrians suffered a "shameful defeat". The rebel triumph broke the back of the Austrian forces in Belgium and many local soldiers within the Austrian force deserted to the patriot cause. Swelled by new recruits and supported by the population, the patriot army advanced rapidly into Flanders. On 16 November, Flander's major city,

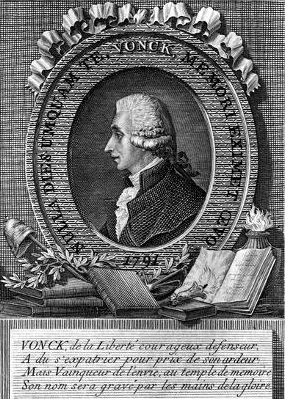

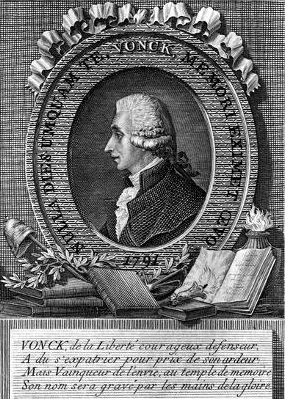

Soon after its establishment, the politics of the United Belgian States became polarised between two opposing factions. The first faction, known as the Vonckists after their leader Vonck, was a "more or less liberal reform party" which believed the revolution represented the triumph of

Soon after its establishment, the politics of the United Belgian States became polarised between two opposing factions. The first faction, known as the Vonckists after their leader Vonck, was a "more or less liberal reform party" which believed the revolution represented the triumph of  The two factions soon clashed over the composition of the provincial assemblies which was "a conflict of which no peaceful solution existed" in the constitution. The Statists accused the Vonckists of sharing the same views as the radicals of the French Revolution. The Statists succeeded in gaining support in a number of Patriotic Associations (''Patriottische Maatschappij''), similar to the "clubs" of Revolutionary France, which were composed of members of the wealthy classes. By March 1790, the Vonckists had been forced out of Brussels by a mob. An armed " crusade" of peasants, carrying crucifixes and led by priests, marched on Brussels in June to confirm their support of the Statists and to display rejection of the Enlightenment. Influenced by the growing power of the radicals in France, the mob believed that the Vonckists were anti-clerical although this was probably untrue.

With the support of the population, Van der Noot launched a persecution of Vonckists known as the Statist

The two factions soon clashed over the composition of the provincial assemblies which was "a conflict of which no peaceful solution existed" in the constitution. The Statists accused the Vonckists of sharing the same views as the radicals of the French Revolution. The Statists succeeded in gaining support in a number of Patriotic Associations (''Patriottische Maatschappij''), similar to the "clubs" of Revolutionary France, which were composed of members of the wealthy classes. By March 1790, the Vonckists had been forced out of Brussels by a mob. An armed " crusade" of peasants, carrying crucifixes and led by priests, marched on Brussels in June to confirm their support of the Statists and to display rejection of the Enlightenment. Influenced by the growing power of the radicals in France, the mob believed that the Vonckists were anti-clerical although this was probably untrue.

With the support of the population, Van der Noot launched a persecution of Vonckists known as the Statist

Just months after its proclamation, in December 1789, the Liège Republic was condemned by the Austrians, and was occupied by troops from neighbouring Prussia. Disagreements between the Prussians and the Prince-Bishop about the form a restoration would take led to a Prussian withdrawal and the revolutionaries soon took power again.

Initially, the Brabant Revolution was also able to continue unthreatened because of the lack of external opposition. Soon after the revolution started, Joseph II had fallen ill. Following its defeats at the hands of the patriot army in the initial campaign, the only Austrian force in the region, taking refuge in Luxembourg, could not challenge the rebels alone. The ongoing conflict with the Ottoman Empire also meant that the bulk of Austria's own army could not be spared to put down the rebellion.

Realising that foreign support would be necessary for the continued existence of the United Belgian States, the Statists tried to make contact with foreign powers they believed to be sympathetic. Despite numerous attempts, however, the revolution failed to gain foreign support. The Dutch were not interested and, although the Prussian king, Frederick William II, was sympathetic and did send some troops to aid the revolutionaries in July, Prussia was also forced to withdraw its forces under combined Austrian and British pressure.

Joseph died in February 1790 and was soon succeeded by his brother Leopold II. Leopold, himself a confirmed liberal, made an armistice with the Turks and withdrew 30,000 troops to repress the rebellion in Brabant. On 27 July 1790, Leopold signed the Reichenbach Convention with Prussia which allowed the Emperor to begin the reconquest of the Austrian Netherlands as long as its local traditions were respected. An amnesty was offered to all revolutionaries who surrendered to the Austrian forces.

The Austrian army, under

Just months after its proclamation, in December 1789, the Liège Republic was condemned by the Austrians, and was occupied by troops from neighbouring Prussia. Disagreements between the Prussians and the Prince-Bishop about the form a restoration would take led to a Prussian withdrawal and the revolutionaries soon took power again.

Initially, the Brabant Revolution was also able to continue unthreatened because of the lack of external opposition. Soon after the revolution started, Joseph II had fallen ill. Following its defeats at the hands of the patriot army in the initial campaign, the only Austrian force in the region, taking refuge in Luxembourg, could not challenge the rebels alone. The ongoing conflict with the Ottoman Empire also meant that the bulk of Austria's own army could not be spared to put down the rebellion.

Realising that foreign support would be necessary for the continued existence of the United Belgian States, the Statists tried to make contact with foreign powers they believed to be sympathetic. Despite numerous attempts, however, the revolution failed to gain foreign support. The Dutch were not interested and, although the Prussian king, Frederick William II, was sympathetic and did send some troops to aid the revolutionaries in July, Prussia was also forced to withdraw its forces under combined Austrian and British pressure.

Joseph died in February 1790 and was soon succeeded by his brother Leopold II. Leopold, himself a confirmed liberal, made an armistice with the Turks and withdrew 30,000 troops to repress the rebellion in Brabant. On 27 July 1790, Leopold signed the Reichenbach Convention with Prussia which allowed the Emperor to begin the reconquest of the Austrian Netherlands as long as its local traditions were respected. An amnesty was offered to all revolutionaries who surrendered to the Austrian forces.

The Austrian army, under

The exiled Vonckists in France embraced the French invasion of the territory as the only way to implement their own objectives, largely forgetting the nationalist dimension of their original ideologies. After the two Belgian revolutions were crushed, a number of Brabant and Liège revolutionaries regrouped in Paris, where they formed the joint Committee of United Belgians and Liégeois (''Comité des belges et liégeois unis''), which united revolutionaries from both territories for the first time. Three Belgian corps and a Liège Legion were levied to continue the fight for the French against the Austrians.

The War of the First Coalition (1792–1797) was the first major effort of multiple European monarchies to defeat Revolutionary France. France declared war on Austria in April 1792, and the

The exiled Vonckists in France embraced the French invasion of the territory as the only way to implement their own objectives, largely forgetting the nationalist dimension of their original ideologies. After the two Belgian revolutions were crushed, a number of Brabant and Liège revolutionaries regrouped in Paris, where they formed the joint Committee of United Belgians and Liégeois (''Comité des belges et liégeois unis''), which united revolutionaries from both territories for the first time. Three Belgian corps and a Liège Legion were levied to continue the fight for the French against the Austrians.

The War of the First Coalition (1792–1797) was the first major effort of multiple European monarchies to defeat Revolutionary France. France declared war on Austria in April 1792, and the

Pirenne, a nationalist himself, argued that the Brabant Revolution was a very important influence on the Belgian Revolution of 1830 and can be seen as an early expression of Belgian nationalism. Pirenne praised the revolution as a unification of

Pirenne, a nationalist himself, argued that the Brabant Revolution was a very important influence on the Belgian Revolution of 1830 and can be seen as an early expression of Belgian nationalism. Pirenne praised the revolution as a unification of

''Observations sur la Révolution Belgique, et réflexions sur un certain imprimé adressé au Peuple Belgique, qui sert de justification au Baron de Schoenfeldt''

(1791, in French, full text) {{Authority control Brabant Brabant Atlantic Revolutions

Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The pe ...

(modern-day Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

) between October 1789 and December 1790. The revolution, which occurred at the same time as revolutions in France and Liège, led to the brief overthrow of Habsburg rule

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

and the proclamation of a short-lived polity, the United Belgian States.

The revolution was the product of opposition which emerged to the liberal reforms of Emperor Joseph II in the 1780s. These were perceived as an attack on the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and the traditional institutions in the Austrian Netherlands. Resistance, focused in the autonomous and wealthy Estates of Brabant and Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

, grew. In the aftermath of rioting and disruption in 1787, known as the Small Revolution, many dissidents took refuge in the neighboring Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

where they formed a rebel army. Soon after the outbreak of the French and Liège revolutions, this ''émigré'' army crossed into the Austrian Netherlands and decisively defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Turnhout in October 1789. The rebels, supported by uprisings across the territory, soon took control over virtually all the Southern Netherlands and proclaimed independence. Despite the tacit support of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, the independent United Belgian States, established in January 1790, received no foreign recognition and the rebels soon became divided along ideological lines. The Vonckists, led by Jan Frans Vonck, advocated progressive and liberal government, whereas the Statists, led by Henri Van der Noot, were staunchly conservative and supported by the Church. The Statists, who had a wider base of support, soon drove the Vonckists into exile through a terror

Terror(s) or The Terror may refer to:

Politics

* Reign of Terror, commonly known as The Terror, a period of violence (1793–1794) after the onset of the French Revolution

* Terror (politics), a policy of political repression and violence

Emoti ...

.

By mid-1790, Habsburg Austria had ended its war with the Ottoman Empire and prepared to suppress the Brabant revolutionaries. The new Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold II, a liberal like his predecessor, proposed an amnesty for the rebels. After a Statist army was overcome at the Battle of Falmagne, the territory was quickly overrun by Imperial forces, and the revolution was defeated by December. The Austrian reestablishment was short-lived, however, and the territory was soon overrun by the French during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

.

Because of its distinctive course, the Brabant Revolution had been extensively used in historical comparisons with the French Revolution. Some historians, following Henri Pirenne, have seen it as a key moment in the formation of a Belgian nation-state, and an influence on the Belgian Revolution

The Belgian Revolution (, ) was the conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces (mainly the former Southern Netherlands) from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

...

of 1830.

Background and causes

Austrian rule

Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The pe ...

was a territory with its capital at Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

which covered much of what is today Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

and Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small land ...

during the Early Modern period. In 1714, the territory, which had been ruled by Spain, was ceded to Austria as part of the Treaty of Rastatt which ended the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phili ...

. In the 1580s, the Dutch Revolt had separated the independent Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

from the rest of the territory, leaving the Austrian Netherlands with a staunchly Catholic population. The clergy maintained substantial power.

The Austrian Netherlands were both a province of Habsburg Austria The term Habsburg Austria may refer to the lands ruled by the Austrian branch of the Habsburgs, or the historical Austria. Depending on the context, it may be defined as:

* The Duchy of Austria, after 1453 the Archduchy of Austria

* The ''Erbland ...

and a part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

. In 1764, Joseph II, was elected as Holy Roman Emperor, ruling over a loosely unified federation of autonomous territories within Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

roughly equivalent to modern-day Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. Th ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. Joseph's mother, Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position '' suo jure'' (in her own right) ...

, had appointed her favourite daughter, Maria Christina, and her husband, Albert Casimir, as joint Governors of the Austrian Netherlands in 1780. Both Joseph and Maria Theresa were considered reformists and were particularly interested in the idea of enlightened absolutism. Joseph II, who was known as the philosopher-emperor (''empereur philosophe''), had a particular interest in Enlightenment thought and had his own ideology which has sometimes been termed " Josephinism" after him. Joseph particularly disliked institutions which he considered "outdated", such as the established ultramontane Church whose allegiance to the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

prevented the Emperor from having total control, which restricted efficient and centralist rule. Soon after taking power, in 1781, Joseph launched a low-key tour of inspection of the Austrian Netherlands during which he concluded reform in the territory was badly needed.

Politically, the Austrian Netherlands comprised a number of federated and autonomous territories, inherited from the Spanish, which could trace their lineage to the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. These territories, known collectively as the Provincial States, retained much of their traditional power over their own internal affairs. The states were dominated by the wealthy and prominent Estates of Brabant and Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

. The Austrian Governors-General were forced to respect the autonomy of the provincial states and could only act with some degree of consent. Within the states themselves, the "traditional" independence was considered extremely important and figures such as Jan-Baptist Verlooy had even begun to claim the linguistic unity of Flemish dialects

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to the region known as Flanders in northern Belgium; it ...

as a sign of national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nation, nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National i ...

in what is now Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

.

Reforms of Joseph II

Propelled by his belief in the Enlightenment, soon after taking power, Joseph launched a number of reforms which he hoped would make the territories he controlled more efficient and easier to govern. From 1784, Joseph launched a number of "radical and wide-ranging" reforms in the fields of economics, politics and religion aimed at institutions which he judged outdated. Some have drawn parallels between Joseph's rule in the Holy Roman Empire and that of Philip II in the Netherlands as both attempted to suborn local traditions in order to achieve more effective central rule. Like Philip, Joseph's perceived attacks on important institutions succeeded in uniting multiple divergent social classes against him.

His initial reforms were aimed at the Catholic church which, because of its allegiance to the Vatican, was viewed a potentially subversive force. Joseph's first act was the proclamation of the Edict of Tolerance of 1781–82 which abolished the privileges which Catholics enjoyed over other Christian and non-Christian minorities. As an attack on the place of the church, it was deeply unpopular among Catholics, but because the non-Catholics were a tiny minority, it did not win any real support. The Edict was condemned by Cardinal Frankenberg who insisted that religious tolerance, the relaxation of censorship and the suppression of laws against the Jansenists all constituted an attack on the Catholic Church. Later, 162 monasteries whose inhabitants led a purely contemplative life were abolished. In September 1784, marriage was made a

Propelled by his belief in the Enlightenment, soon after taking power, Joseph launched a number of reforms which he hoped would make the territories he controlled more efficient and easier to govern. From 1784, Joseph launched a number of "radical and wide-ranging" reforms in the fields of economics, politics and religion aimed at institutions which he judged outdated. Some have drawn parallels between Joseph's rule in the Holy Roman Empire and that of Philip II in the Netherlands as both attempted to suborn local traditions in order to achieve more effective central rule. Like Philip, Joseph's perceived attacks on important institutions succeeded in uniting multiple divergent social classes against him.

His initial reforms were aimed at the Catholic church which, because of its allegiance to the Vatican, was viewed a potentially subversive force. Joseph's first act was the proclamation of the Edict of Tolerance of 1781–82 which abolished the privileges which Catholics enjoyed over other Christian and non-Christian minorities. As an attack on the place of the church, it was deeply unpopular among Catholics, but because the non-Catholics were a tiny minority, it did not win any real support. The Edict was condemned by Cardinal Frankenberg who insisted that religious tolerance, the relaxation of censorship and the suppression of laws against the Jansenists all constituted an attack on the Catholic Church. Later, 162 monasteries whose inhabitants led a purely contemplative life were abolished. In September 1784, marriage was made a civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

, rather than a religious, institution. This sharply reduced the church's traditional influence and power in its parishioners' family lives. Following this, in October 1786, the government abolished all seminaries in the territory to establish a single, state-run General Seminary (''seminarium generale'') in Leuven

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. Th ...

. Within the General Seminary, training would be in liberal and state-approved theology which was opposed by the upper ranks of the clergy.

In December 1786, he followed up his belief in liberalisation and earlier attacks on guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

privileges by removing all tariffs on grain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, barley, maize, and rice. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike othe ...

, but this was revoked in the economic slump that soon followed. Replaced local charity or poor-relief organisations with a single, central Brotherhood of Active Charity in April 1786. Schools were reformed.

Above all, however, Joseph attempted to break up the structure of autonomous states which provided the framework for the Austrian Netherlands. He introduced two reforms in early 1787 instituting new administrative and judicial reform to create a much more centralised system. The first decree abolished many of the administrative structures which had existed since the rule of Emperor Charles V (1500–58) and replaced them by a single General Council of Government under a minister-plenipotentiary. In addition, nine administrative circles (''cercles''), each controlled by an Intendant, were created to which much of the power of the states was devolved. A second decree abolished the ''ad hoc'' semi-feudal or ecclesiastical courts operated by the states and replaced them with a centralised system similar to that already in place in Austria. A single Sovereign Council of Justice was established in Brussels, with two appeal courts in Brussels and Luxembourg, and around 40 local district courts.

By threatening the independence of the states, the interests of the nobility and the position of the church, the reforms acted as a force to unite these groups against the Austrian government.

Opposition and the Small Revolution

bill of rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

for the region.

Discontent crystallised into a wave of uprisings and rioting known as the Small Revolution (''Kleine Revolutie'') of 1787. The revolution was suppressed by levying the civil militias but it alarmed the Governors-General and opposition grew. The Small Revolution proved that the Austrian army was insufficient on its own to keep order without some popular support. The allegiance of the civil militias, who were already beginning to call themselves Patriots (''Patriotten''), was uncertain. Fearing for the security of the regime, the Governors-General temporarily suspended the reforms without the Emperor's permission on 20 May 1787. They invited all aggrieved parties to express their opposition and grievances in petitions but this merely inflamed the regime's critics. The Emperor himself was furious and recalled his minister, Ludovico, Count di Belgiojoso. Alarmed by the level of unrest, Joseph eventually agreed to repeal his reforms to the judicial system and governance but left his clerical reforms in place. He hoped that, by removing the grievances of the states and middle classes, the opposition would become divided and would be easily suppressed. He also appointed a new Minister Plenipotentiary to oversee the province. The concession did not stop the opposition growing, inspired and funded by the Catholic clergy, which became especially notable at the University of Leuven.

Between 1788 and 1789, the Minister-Plenipotentiary of the Austrian Netherlands decided that the only way in which reform could be provoked would be by rapid and uncompromising enforcement. Some states had already begun to refuse payment of taxes to the Austrian authorities. The Joyous Entry was officially annulled and the Estates of Hainaut and Brabant were disbanded.

Growth of organised resistance and the ''émigrés''

In the aftermath of the suppression of the Small Revolution, opposition began to consolidate into more organised resistance. Fearing for his safety, Van der Noot, the organiser of the disruption of 1787, went into exile in the Dutch Republic where he tried to lobby support from William V. Van der Noot attempted to persuade William to support the overthrow of the Austrian regime and install his son, Frederick, as ''

In the aftermath of the suppression of the Small Revolution, opposition began to consolidate into more organised resistance. Fearing for his safety, Van der Noot, the organiser of the disruption of 1787, went into exile in the Dutch Republic where he tried to lobby support from William V. Van der Noot attempted to persuade William to support the overthrow of the Austrian regime and install his son, Frederick, as ''Stadtholder

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and ...

'' of a Belgian republic. However, William was suspicious and expressed little interest in Van der Noot's proposal. None of the political factions in Dutch society proclaimed support for similar proposal. Nevertheless, Van der Noot was able to set up a headquarters in the city of Breda, near the Dutch-Belgian border, where an '' émigré'' faction grew. The Dutch population also remained broadly sympathetic towards the patriots. As disquiet in the Austrian Netherlands grew, thousands of Flemish and Brabant dissidents fled into the Dutch Republic to join the growing patriot army at Breda although the force remained relatively small.

Inside the Austrian Netherlands themselves, the lawyers Jan Frans Vonck and Verlooy formed a secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ...

called '' Pro Aris et Focis'' in April or May 1789 in order to plan for an armed uprising against Austrian rule. Weapons and revolutionary tracts were distributed. Most of the members of the organisation came from the liberal professions (such as lawyers, writers and merchants). Most were moderates who did not object to Joseph II's reforms in principle but because they had been levied on the territories without consultation. They were supported financially by the clergy. Initially members of the opposition were divided on how the uprising should occur. Unlike Van der Noot, Vonck believed that Belgium should liberate itself rather than rely on foreign aid.

With the support of the Belgian clergy, all the opposition factions (including Van der Noot) agreed to unite and a Brabant Patriot Committee (''Brabants patriottisch Comité'') was formed in Hasselt

Hasselt (, , ; la, Hasseletum, Hasselatum) is a Belgian city and municipality, and capital and largest city of the province of Limburg in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is known for its former branding as "the city of taste", as well as ...

. On 30 August, ''Pro Aris et Focis'' voted to install Jean-André van der Mersch Jean-André is a French masculine given name. It may refer to:

* Jean-André Cuoq (1821–1898), French philologist

* Jean-André Deluc (1727–1817), Swiss geologist and meteorologist

* Jean-André Mongez (1750–1788), French priest and mineral ...

(or Vandermersch), a retired military officer, as the commander of the ''émigré'' army in Breda. The Committee agreed that the rebellion should begin in October 1789.

Revolution

In the spring of 1789, a revolution broke out in France against the Bourbon regime of King Louis XVI. In August 1789, the inhabitants of thePrince-Bishopric of Liège

The Prince-Bishopric of Liège or Principality of Liège was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that was situated for the most part in present-day Belgium. It was an Imperial Estate, so the bishop of Liège, as its prince ...

also overthrew their tyrannical Prince-Bishop, César-Constantin-François de Hoensbroeck

César-Constantin-François de Hoensbroeck or Hoensbroech (28 August 1724 – 3 June 1792) was a German ecclesiastic of the Van Hoensbroeck family, most notable as prince-bishop of Liège from 1784 to 1792, in which post he was nicknamed the "re ...

, in a bloodless coup d'état known as the " Happy Revolution" (''Heureuse révolution''). Contemporaries viewed the uprising in Liège, which was also inspired by Enlightenment ideas, as a symptom of revolutionary "contagion" from France. In the face of a rebellion proclaiming the ideas of liberty and equality, the Prince-Bishop soon fled to the neighboring Archbishopric of Trier and the revolutionaries proclaimed a republic in Liège.

Invasion

The Brabant Revolution broke out on 24 October 1789 when the ''émigré'' patriot army under Van der Mersch crossed over the Dutch border into the Austrian Netherlands. The army, which numbered 2,800 men, crossed into the Kempen region south of Breda. The army arrived in the town of Hoogstraten where a specially prepared document, the Manifesto of the People of Brabant (''Manifeste du peuple brabançon''), was read in the city hall. The document denounced Joseph II's rule and declared that he no longer held legitimacy. The text of the speech itself was an embellished version of the 1581 declaration (the ''Verlatinge'') by the Dutch States-General denouncing Philip II's rule in the Netherlands.

On 27 October, the patriot army clashed with a much-larger Austrian force at the nearby town of Turnhout. The ensuing battle was a triumph for the outnumbered rebels and the Austrians suffered a "shameful defeat". The rebel triumph broke the back of the Austrian forces in Belgium and many local soldiers within the Austrian force deserted to the patriot cause. Swelled by new recruits and supported by the population, the patriot army advanced rapidly into Flanders. On 16 November, Flander's major city,

The Brabant Revolution broke out on 24 October 1789 when the ''émigré'' patriot army under Van der Mersch crossed over the Dutch border into the Austrian Netherlands. The army, which numbered 2,800 men, crossed into the Kempen region south of Breda. The army arrived in the town of Hoogstraten where a specially prepared document, the Manifesto of the People of Brabant (''Manifeste du peuple brabançon''), was read in the city hall. The document denounced Joseph II's rule and declared that he no longer held legitimacy. The text of the speech itself was an embellished version of the 1581 declaration (the ''Verlatinge'') by the Dutch States-General denouncing Philip II's rule in the Netherlands.

On 27 October, the patriot army clashed with a much-larger Austrian force at the nearby town of Turnhout. The ensuing battle was a triumph for the outnumbered rebels and the Austrians suffered a "shameful defeat". The rebel triumph broke the back of the Austrian forces in Belgium and many local soldiers within the Austrian force deserted to the patriot cause. Swelled by new recruits and supported by the population, the patriot army advanced rapidly into Flanders. On 16 November, Flander's major city, Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest i ...

, was taken after four days of fighting and the Estate of Flanders proclaimed support for the rebel cause. The rebel armies penetrated further into the territory, defeating Austrian forces in a number of small skirmishes, and captured the town of Mons

Mons (; German and nl, Bergen, ; Walloon and pcd, Mont) is a city and municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

Mons was made into a fortified city by Count Baldwin IV of Hainaut in the 12th century. ...

on 21 November. By December, the Austrian force, fully routed, withdrew to the fortified city of Luxembourg in the south, abandoning the rest of the territory to the patriots.

Historians have pointed to the deliberate parallels between the entrance of the rebel army into the Austrian Netherlands in 1789 and Louis of Nassau's invasion of Frisia in 1566 which acted as the trigger for the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule.

United Belgian States

With fall of the Austrian regime, the revolutionaries were forced to decide what form a new revolutionary state would take. Figures within revolutionary France, such as Jacques Pierre Brissot, praised their work and encouraged them to declare their own national independence in the spirit of theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

. On 30 November, a Declaration of Unity was signed between Flanders and the Brabant states. On 20 December, an actual declaration of independence was signed proclaiming the end of Austrian rule and the independence of the states.

After the rebel capture of Brussels on 18 December, work soon began on a new constitution. In January, the rebels re-called the States-General, a traditional assembly composed of the provincial elites which had not met since the Middle Ages, to discuss the form the new state would take. Its 53 members, representing the states and social classes, met in Brussels in January 1790 to begin negotiations. The constitution eventually devised by the States-General was inspired by both the Dutch ''Verlatinge'' of 1581 and American Declaration of Independence of 1776. The liberals were disgusted that members of society from beyond the guilds, clergy and nobility should not be consulted. They also saw the closed sessions of the States-General as ridiculing the idea of popular sovereignty. The declaration of the independence was not supported by Britain and the Dutch who believed that the new independent state would not be able to act as an effective buffer against possible French territorial expansion in the region.

On 11 January 1790, the United Belgian States (''État-Belgiques-Unis'' or ''Verenigde Nederlandse Staten'') was officially formed with a Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

. After negotiations, the delegates decided that the states should be unified into a single polity. A Sovereign Congress was created in Brussels which would act as a parliament for the whole union. Autonomy over almost all important matters, however, was still decided independently by the states themselves.

Growing divisions and factionalism

Soon after its establishment, the politics of the United Belgian States became polarised between two opposing factions. The first faction, known as the Vonckists after their leader Vonck, was a "more or less liberal reform party" which believed the revolution represented the triumph of

Soon after its establishment, the politics of the United Belgian States became polarised between two opposing factions. The first faction, known as the Vonckists after their leader Vonck, was a "more or less liberal reform party" which believed the revolution represented the triumph of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

. They derived much of their support from the liberal middle classes and hoped that the revolution would allow their supporters to achieve political power traditionally monopolised by the clergy and aristocracy. Most had not disagreed with Joseph's reforms in principal, but believed that the way in which they had been implemented was arbitrary and showed disregard for his subjects. Traditionally, much of the Vonckists' support was based in Flanders which was considered more liberal than Brabant.

Opposed to the Vonckists were the more conservative Statists (sometimes also known as "Aristocrats"), led by Van der Noot. The Statists had a broader base of support than the Vonckists and were particularly supported by the clergy, lower classes, nobility and the feudal corporations. The Statists viewed the revolution as a purely reactive measure to reforms which they considered unacceptable. Most Statists supported the maintenance of traditional aristocratic privilege and the position of the Church.

Terror

Terror(s) or The Terror may refer to:

Politics

* Reign of Terror, commonly known as The Terror, a period of violence (1793–1794) after the onset of the French Revolution

* Terror (politics), a policy of political repression and violence

Emoti ...

(''Statistisch Schrikbewind''). Verlooy and Vandermersh were arrested and imprisoned. Vonck and his remaining supporters forced into exile in Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the Nord ...

where they tried to raise opposition to the Statists but in vain. Faced with an increasingly reactionary government in the United Belgian States, many of the exiled Vonckists felt that they had more to gain from negotiating with the Austrians than with the Statists. Amid rumours of Austrian military forces nearing Belgium, the Statists put their faith in a foreign military intervention and began lobbying the Prussians, who were believed to be sympathetic, for support.

Suppression

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered a ...

Blasius Columban, Baron von Bender, invaded in the United Belgian States and encountered little resistance from the population which was already discontented with the governance and infighting of the rebels. The Austrians defeated the Statist army at the Battle of Falmagne on 28 September. Hainaut was the first to recognise Leopold's sovereignty and other cities soon followed. Namur was captured on 24 November. The Sovereign Congress met for the final time on 27 November before disbanding itself. On 3 December, the Austrians accepted the surrender of Brussels and reoccupied the city, effectively marking the suppression of the revolution.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the defeat of the United Belgian States, a convention was held atThe Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

on 10 December 1790 to decide what form the Austrian reestablishment would take. The Convention, which included representatives of the Emperor and the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

of the Dutch, British and Prussians, eventually decided to cancel most of Joseph II's reforms. Despite the Austrian reestablishment, anti-government pamphleting continued. The Dutch radical Gerrit Paape published his detailed observations on the uprising and observed that a new revolution was needed in which the "happiness and freedom of peoples" were respected. The Liège Revolution was also finally suppressed by Austrian forces in January 1791 and its Prince-Bishop reinstated.

French invasion

The exiled Vonckists in France embraced the French invasion of the territory as the only way to implement their own objectives, largely forgetting the nationalist dimension of their original ideologies. After the two Belgian revolutions were crushed, a number of Brabant and Liège revolutionaries regrouped in Paris, where they formed the joint Committee of United Belgians and Liégeois (''Comité des belges et liégeois unis''), which united revolutionaries from both territories for the first time. Three Belgian corps and a Liège Legion were levied to continue the fight for the French against the Austrians.

The War of the First Coalition (1792–1797) was the first major effort of multiple European monarchies to defeat Revolutionary France. France declared war on Austria in April 1792, and the

The exiled Vonckists in France embraced the French invasion of the territory as the only way to implement their own objectives, largely forgetting the nationalist dimension of their original ideologies. After the two Belgian revolutions were crushed, a number of Brabant and Liège revolutionaries regrouped in Paris, where they formed the joint Committee of United Belgians and Liégeois (''Comité des belges et liégeois unis''), which united revolutionaries from both territories for the first time. Three Belgian corps and a Liège Legion were levied to continue the fight for the French against the Austrians.

The War of the First Coalition (1792–1797) was the first major effort of multiple European monarchies to defeat Revolutionary France. France declared war on Austria in April 1792, and the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) constituted the German state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: ...

joined the Austrian side a few weeks later. France was attacked by Prussian and Holy Roman forces from the Austrian Netherlands. Though the French defeated the Austrian army in the Battle of Jemappes in 1792 and briefly occupied the Austrian Netherlands and Liège, they were pushed out by an Austrian counterattack in the Battle of Neerwinden the following year. In June 1794, French revolutionary troops expelled Holy Roman forces from the region for the last time after the Battle of Fleurus. The French government voted to formally annex the territory in October 1795 and it was split into nine provincial '' départements'' within France. French rule in the region, known as the French period (''Franse tijd'' or ''période française''), was marked by the rapid implementation and extension of numerous reforms which had been passed in post-Revolution France since 1789. Administration was organised under the French model, with meritocratic selection. Legal equality and state secularism were also introduced.

Legacy

After the defeat of the French in theNapoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

in 1815, Belgium came under Dutch rule. The Belgian Revolution

The Belgian Revolution (, ) was the conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces (mainly the former Southern Netherlands) from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

...

, which broke out on 25 August 1830 after the performance of a nationalist opera in Brussels led to a minor insurrection among the capital's bourgeoisie, was inspired to some extent by the Brabant Revolution. The day after the revolution broke out, revolutionaries began flying their own flag, clearly influenced by the colours chosen by the Brabant Revolution of 1789. The colours (red, yellow and black) today form the national flag of Belgium. Some historians have also argued that the Vonckists and Statists were the forerunners of the major political factions, the Liberals and the Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, which would dominate Belgian politics after independence.

Historical analysis

The Brabant Revolution has been extensively used for historical comparisons with other revolutions of the time. The leading Belgian historian, Henri Pirenne, contrasted the Brabant Revolution, which he termed "defensive" or "conservative", with the more enlightened uprisings in France and Liège in his '' Histoire de Belgique'' series. Other historians have agreed, commenting that the Brabant revolutionaries had an ideology which was deliberately opposed to the Enlightened and Democratic vision of the French Revolutionaries. The historians Jacques Godechot and Robert Roswell Palmer characterised the ideology of the French revolutionaries as founded on beliefs in the "enlightenment" and "national consciousness". Palmer argued for similarities between the Brabant Revolution and the counter-revolutionary activities of pre-revolutionary institutions, like the guilds and the aristocracy, in France which were ultimately defeated and abolished. Some historians have similarly drawn parallels between the Brabant Revolution and the French counter-revolutions in the Vendée. Other historians, likeE. H. Kossmann

Ernst Heinrich Kossmann (31 January 1922 – 8 November 2003), often named as E. H. Kossmann in his books, was a Dutch historian. He was professor of Modern History at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. His magnum opus is ''The Low Co ...

, have noted similarities between the uprising and the Dutch Revolt. It has also been argued that the Brabant Revolution might form part of the same Europe-wide "crisis of the ''ancien régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

''" which sparked the French Revolution.

Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium ...

and Walloons

Walloons (; french: Wallons ; wa, Walons) are a Gallo-Romance ethnic group living native to Wallonia and the immediate adjacent regions of France. Walloons primarily speak '' langues d'oïl'' such as Belgian French, Picard and Walloon. Wal ...

. He also argued that the Vonckists and Statists could be seen as the forerunners of the major political factions of Belgium post-independence, the Liberals and Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and expressed sympathy with the Vonckists. Pirenne, as a liberal, could only explain the defeat of the Vonckists by playing up the economic and social backwardness of the Austrian Netherlands. He supported this viewpoint by emphasizing the disgust seen in traveler's tales written by "enlightened" German observers. This has been criticised by modern historians, like J. Craeybeckx, who argue that France was no more socially or economically advanced than the Austrian Netherlands at the time.

Conceptually, the Brabant Revolution has generally been seen as a "revolution from above", based on the defense of existing privileges and the upper classes and clergy rather than the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

. Kossmann argued that, while it was Vonck who began the revolution, it was Van der Noot who was best able to shape it. In his belief, this was because Vonck was able to rally mass support against the Austrians, but not in support of his own policies unlike Van der Noot. It has also been argued that the revolution's ideology was framed in direct opposition to the democratic and liberal revolutions in France, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the German states.

See also

*'' Patriottentijd'' (1780–87) – contemporary political unrest in the Dutch Republic * Peasants' War (1798) * Belgium in the long nineteenth century * List of revolutions and rebellionsNotes and references

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *Primary sources

* Lochée, Lewis''Observations sur la Révolution Belgique, et réflexions sur un certain imprimé adressé au Peuple Belgique, qui sert de justification au Baron de Schoenfeldt''

(1791, in French, full text) {{Authority control Brabant Brabant Atlantic Revolutions