Bowdoin College on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bowdoin College ( ) is a

Bowdoin College was chartered in 1794 by the

Bowdoin College was chartered in 1794 by the  Harriet Beecher Stowe started writing her influential anti-slavery novel, ''

Harriet Beecher Stowe started writing her influential anti-slavery novel, ''

Although Bowdoin's Medical School of Maine closed its doors in 1921, it produced Dr.

Although Bowdoin's Medical School of Maine closed its doors in 1921, it produced Dr.

Bowdoin's dining services have been ranked #1 among all universities and colleges nationally by ''

Bowdoin's dining services have been ranked #1 among all universities and colleges nationally by ''

The largest student group on campus is the Outing Club, which leads canoeing, kayaking, rafting, camping, and backpacking trips throughout Maine. One of the school's two historic rival literary societies, The Peucinian Society, has recently been revitalized from its previous form. The Peucinian Society was founded in 1805. This organization counts such people as

The largest student group on campus is the Outing Club, which leads canoeing, kayaking, rafting, camping, and backpacking trips throughout Maine. One of the school's two historic rival literary societies, The Peucinian Society, has recently been revitalized from its previous form. The Peucinian Society was founded in 1805. This organization counts such people as

Organized athletics at Bowdoin began in 1828 with a gymnastics program established by the "father of athletics in Maine," John Neal. In the proceeding years, Neal agitated for more programs, and himself taught

Organized athletics at Bowdoin began in 1828 with a gymnastics program established by the "father of athletics in Maine," John Neal. In the proceeding years, Neal agitated for more programs, and himself taught

File:Mathew Brady - Franklin Pierce - alternate crop.jpg, Franklin Pierce, 14th

Notable Bowdoin alumni include (by year of graduation):

* U.S. Secretary of Treasury, U.S. Representative, & U.S. Senator from Maine Donald M. Zuckert

(1956) * U.S. Senator and Secretary of Defense

Official athletics website

{{authority control 1794 establishments in Massachusetts Education in Brunswick, Maine Educational institutions established in 1794 Liberal arts colleges in Maine Private universities and colleges in Maine Tourist attractions in Brunswick, Maine Universities and colleges in Cumberland County, Maine

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine

Brunswick is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The population was 21,756 at the 2020 United States Census. Part of the Portland-South Portland-Biddeford metropolitan area, Brunswick is home to Bowdoin College, the Bowdoin Intern ...

. When Bowdoin was chartered in 1794, Maine was still a part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. The college offers 34 majors and 36 minors, as well as several joint engineering programs with Columbia, Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

, Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

, and the University of Maine

The University of Maine (UMaine or UMO) is a public land-grant research university in Orono, Maine. It was established in 1865 as the land-grant college of Maine and is the flagship university of the University of Maine System. It is classifie ...

.

The college was a founding member of its athletic conference

An athletic conference is a collection of sports teams, playing competitively against each other in a sports league. In many cases conferences are subdivided into smaller divisions, with the best teams competing at successively higher levels. Conf ...

, the New England Small College Athletic Conference

The New England Small Collegiate Athletic Conference (NESCAC) is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising sports teams from eleven highly selective liberal arts institutions of higher education in the Northeastern United States. ...

, and the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium

The Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium (CBB) is an athletic conference and academic consortium between three private liberal arts colleges in the U.S. State of Maine. The group consists of Colby College in Waterville, Bates College in Lewiston, ...

, an athletic conference and inter-library exchange with Bates College

Bates College () is a private liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian Houses as some of the dormitories. It maintains of nature p ...

and Colby College

Colby College is a private liberal arts college in Waterville, Maine. It was founded in 1813 as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution, then renamed Waterville College after the city where it resides. The donations of Christian philant ...

. Bowdoin has over 30 varsity teams, and the school mascot was selected as a polar bear in 1913 to honor Robert Peary, a Bowdoin alumnus who led the first successful expedition to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

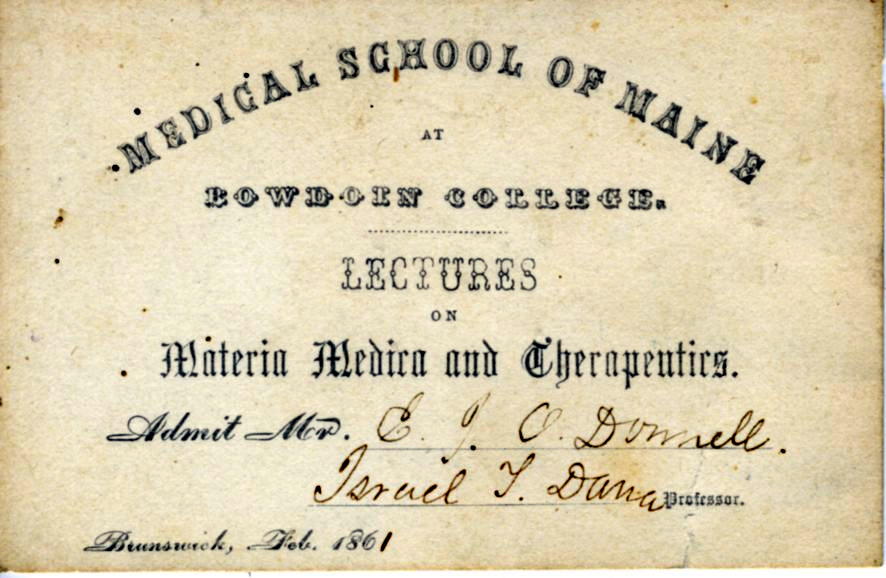

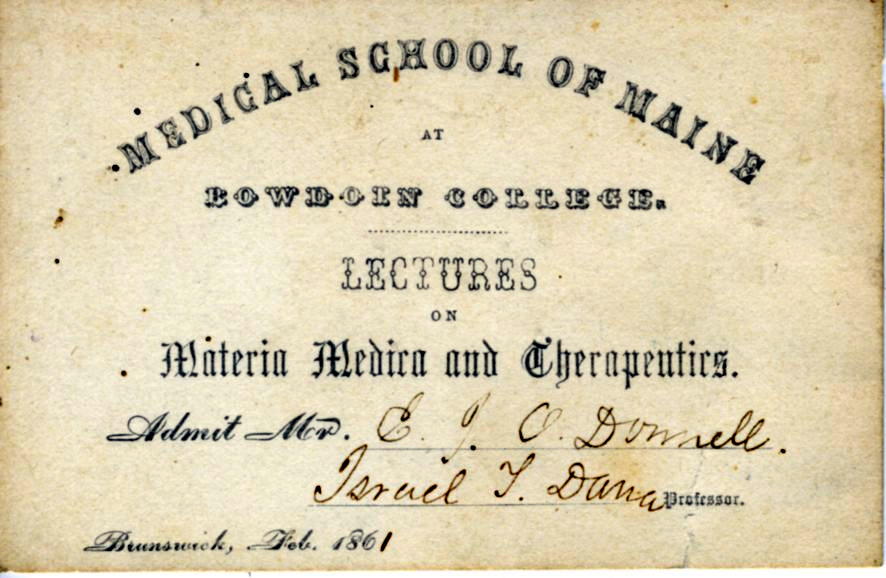

. Between the years 1821 and 1921, Bowdoin operated a medical school called the Medical School of Maine.

The main Bowdoin campus is located near Casco Bay

Casco Bay is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine on the southern coast of Maine, New England, United States. Its easternmost approach is Cape Small and its westernmost approach is Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth. The city of Portland sits along its s ...

and the Androscoggin River

The Androscoggin River ( Abenaki: ''Aləssíkαntekʷ'') is a river in the U.S. states of Maine and New Hampshire, in northern New England. It is U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, ...

. In addition to its Brunswick campus, Bowdoin owns a coastal studies center on Orr's Island and a scientific field station on Kent Island

Kent Island is the largest island in the Chesapeake Bay and a historic place in Maryland. To the east, a narrow channel known as the Kent Narrows barely separates the island from the Delmarva Peninsula, and on the other side, the island is sep ...

in the Bay of Fundy.

History

Founding and 19th century

Bowdoin College was chartered in 1794 by the

Bowdoin College was chartered in 1794 by the Massachusetts State Legislature

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, ...

and was later redirected under the jurisdiction of the Maine Legislature

The Maine Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maine. It is a bicameral body composed of the lower house Maine House of Representatives and the upper house Maine Senate. The Legislature convenes at the State House in Augus ...

. It was named for former Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin

James Bowdoin II (; August 7, 1726 – November 6, 1790) was an American political and intellectual leader from Boston, Massachusetts, during the American Revolution and the following decade. He initially gained fame and influence as a wealthy ...

, whose son James Bowdoin III

James Bowdoin III (September 22, 1752 – October 11, 1811) was an American philanthropist and statesman from Boston, Massachusetts. He has born to James Bowdoin in Boston, and graduated from Harvard College in 1771. James then studied law at Oxf ...

was an early benefactor. At the time of its founding, it was the easternmost college in the United States, as it was located in Maine.

Bowdoin began to develop in the 1820s, a decade in which Maine became an independent state as a result of the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

and graduated U.S. President Franklin Pierce. The college also graduated two literary philosophers, the writers Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

, both of whom graduated Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

in 1825. Pierce and Hawthorne began an official militia company called the 'Bowdoin Cadets'.

From its founding, Bowdoin was known to educate the sons of the political elite and "catered very largely to the wealthy conservative from the state of Maine." During the first half of the 19th century, Bowdoin required of its students a certificate of "good moral character" as well as knowledge of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

, geography, algebra, and the major works of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

.

Harriet Beecher Stowe started writing her influential anti-slavery novel, ''

Harriet Beecher Stowe started writing her influential anti-slavery novel, ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'', in Brunswick while her husband was teaching at the college, and Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

(and Brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

) Joshua Chamberlain

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (born Lawrence Joshua Chamberlain, September 8, 1828February 24, 1914) was an American college professor from Maine who volunteered during the American Civil War to join the Union Army. He became a highly respected and ...

, a Bowdoin alumnus and professor, was present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

at Appomattox Court House in 1865. Chamberlain, a Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

recipient who later served as governor of Maine

The governor of Maine is the head of government of the U.S. state of Maine. Before Maine was admitted to the Union in 1820, Maine was part of Massachusetts and the governor of Massachusetts was chief executive.

The current governor of Maine is J ...

, adjutant-general of Maine, and president of Bowdoin, fought at Gettysburg, where he was in command of the 20th Maine in defense of Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the companion to the adjacent, taller hill named Big Round Top. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left f ...

. Major General Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men agains ...

, class of 1850, led the Freedmen's Bureau after the war and later founded Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

; Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, class of 1837, was responsible for the formation of the 54th Massachusetts; and William P. Fessenden (1823) and Hugh McCulloch

Hugh McCulloch (December 7, 1808 – May 24, 1895) was an American financier who played a central role in financing the American Civil War. He served two non-consecutive terms as U.S. Treasury Secretary under three presidents. He was originally ...

(1827) both served as Secretary of the Treasury during the Lincoln Administration

The presidency of Abraham Lincoln began on March 4, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States, and ended upon his assassination and death on April 15, 1865, days into his second term. Lincoln was th ...

. However, the college's involvement in the Civil War was mixed, as Bowdoin had many ties to slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and the Confederacy.

With strained slave-relations between political parties, President Franklin Pierce appointed Jefferson Davis as his Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, and the college awarded the soon-to-be President of the Confederacy an honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

. The Jefferson Davis Award was given to a student who excelled in legal studies after a donation was given to the college by the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

. The award, however, was discontinued in 2015, with the current college president citing it as inappropriate because it was named after someone "whose mission was to preserve and institutionalize slavery". President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, too, was given an honorary degree from the college in 1865. Seventeen Bowdoin alumni attained the rank of brigadier general during the Civil War, including James Deering Fessenden and Francis Fessenden

Francis Fessenden (March 18, 1839 – January 2, 1906) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier from the state of Maine who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.Eicher, p. 234. He was a member of the powe ...

; Ellis Spear

Ellis Spear (October 15, 1834 – April 3, 1917) was an officer in the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War. On April 10, 1866, the United States Senate confirmed President Andrew Johnson's Februar ...

, class of 1858, who served as Chamberlain's second-in-command at Gettysburg; and Charles Hamlin, class of 1857, son of Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 15th vice president of the United States from 1861 to 1865, during President Abraham Lincoln's first term. He was the first Republican ...

.

20th century

Although Bowdoin's Medical School of Maine closed its doors in 1921, it produced Dr.

Although Bowdoin's Medical School of Maine closed its doors in 1921, it produced Dr. Augustus Stinchfield

Augustus W. Stinchfield (December 21, 1842 – March 15, 1917) was an American physician and one of the co-founders—along with Drs. Charles Horace Mayo, William James Mayo, Christopher Graham, E. Starr Judd, Henry Stanley Plummer, Melvin ...

, who received his M.D.

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. ...

in 1868 and became one of the co-founders of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. In 1877, the college would go on to graduate the infamous Charles Morse, the American banker who established a near-monopoly of the ice business in New York, which directly led to the financial Panic of 1907. Another scientific alumnus is the controversial entomologist-turned-sexologist Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey (; June 23, 1894 – August 25, 1956) was an American sexologist, biologist, and professor of entomology and zoology who, in 1947, founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Insti ...

, class of 1916.

The college went on to educate and eventually graduate Arctic explorers Robert E. Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is best known for, in Apri ...

, class of 1877, and Donald B. MacMillan

Donald Baxter MacMillan (November 10, 1874 – September 7, 1970) was an American explorer, sailor, researcher and lecturer who made over 30 expeditions to the Arctic during his 46-year career.

He pioneered the use of radios, airplanes, an ...

, class of 1898. Robert Peary named Bowdoin Fjord

Bowdoin Fjord is a fjord in northern Greenland. To the south the fjord opens into the Inglefield Gulf of the Baffin Bay. GoogleEarth

This fjord was named by Robert Peary after his alma mater, Bowdoin College. It was the subject of paintings by ...

and Bowdoin Glacier

Bowdoin Glacier ( da, Bowdoin Gletscher or ''Bowdoin Brae''), is a glacier in northwestern Greenland. Administratively it belongs to the Avannaata municipality.

Like the fjord further south, this glacier was named by Robert Peary after Bowdoin ...

after his alma mater. Peary led the first successful expedition to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

in 1908, and MacMillan, a member of Peary's crew, explored Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

, Baffin Island, and Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

in the schooner ''Bowdoin'' between 1908 and 1954. Bowdoin's Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum

The Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum is a museum located in Hubbard Hall at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. Named after Arctic explorers and Bowdoin College graduates Robert E. Peary (Class of 1877) and Donald B. MacMillan (Class of 1898), ...

honors the two explorers, and the college's mascot, the polar bear, was chosen in 1913 to honor MacMillan, who donated a statue of a polar bear to his alma mater in 1917.

Wallace H. White, Jr.

Wallace Humphrey White Jr. (August 6, 1877March 31, 1952) was an Politics of the United States, American politician and Republican Party (United States), Republican leader in the United States Congress from 1917 until 1949. White was from the U.S ...

, class of 1899, served as Senate Minority Leader from 1944 to 1947 and Senate Majority Leader from 1947 to 1949; George J. Mitchell

George John Mitchell Jr. (born August 20, 1933) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. A leading member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Maine from 1980 to 1995, and as Senate Majority Leader from 19 ...

, class of 1954, served as Senate Majority Leader from 1989 to 1995 before assuming an active role in the Northern Ireland peace process; and William Cohen

William Sebastian Cohen (born August 28, 1940) is an American lawyer, author, and politician from the U.S. state of Maine. A Republican, Cohen served as both a member of the United States House of Representatives (1973–1979) and Senate (1979� ...

, class of 1962, spent twenty-five years in the House and Senate before being appointed Secretary of Defense in the Clinton Administration.

In 1970, the college became one of a very limited number of liberal arts colleges to make the SAT

The SAT ( ) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since its debut in 1926, its name and scoring have changed several times; originally called the Scholastic Aptitude Test, it was later called the Schol ...

optional in the admissions process, and in 1971, after nearly 180 years as a small men's college, Bowdoin admitted its first class of women. Bowdoin also phased out fraternities

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity ...

in 1997, replacing them with a system of college-owned social houses.

In 1970, Bowdoin began competing in the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium

The Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium (CBB) is an athletic conference and academic consortium between three private liberal arts colleges in the U.S. State of Maine. The group consists of Colby College in Waterville, Bates College in Lewiston, ...

, with Bates and Colby. The consortium became both an athletic rivalry and an academic exchange program. The three schools have produced numerous athletic competitions, most notably a football championship game and the Chase Regatta.

21st century

In 2001, Barry Mills, class of 1972, was appointed as the fifth alumnus president of the college. On January 18, 2008, Bowdoin announced that it would eliminate loans for all new and current students receiving financial aid, replacing those loans with grants beginning with the 2008–2009 academic year. President Mills stated, "Some see a calling in such vital but often low paying fields such as teaching or social work. With significant debt at graduation, some students will undoubtedly be forced to make career or education choices not based on their talents, interests, and promise in a particular field but rather on their capacity to repay student loans. As an institution devoted to the common good, Bowdoin must consider the fairness of such a result." In February 2009, following a US$10 million donation (equivalent to $ million in ) by Subway Sandwiches co-founder and alumnusPeter Buck

Peter Lawrence Buck (born December 6, 1956) is an American musician and songwriter. He was a co-founder and the lead guitarist of the alternative rock band R.E.M. He also plays the banjo and mandolin on several R.E.M. songs. Throughout his ca ...

, class of 1952, the college completed a $250-million capital campaign. Additionally, the college has also recently completed major construction projects on the campus, including a renovation of the college's art museum and a new fitness center named after Peter Buck.

On July 1, 2015, Clayton Rose

Clayton S. Rose is an American academic administrator serving as the 15th president of Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine.

Early life and education

Originally from San Rafael, California, Rose graduated from the University of Chicago as an und ...

succeeded Mills as president.

Admissions

The acceptance rate for the class of 2023 was 8.9 percent. The applicant pool consisted of 9,332 candidates, up from 9,081 for the class of 2022. '' U.S. News & World Report'' classifies Bowdoin as "most selective." Of enrolling students, 89% are in the top 10% of their high school graduating class. Although Bowdoin does not require theSAT

The SAT ( ) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since its debut in 1926, its name and scoring have changed several times; originally called the Scholastic Aptitude Test, it was later called the Schol ...

in admissions, all students must submit a score upon matriculation. The middle 50% SAT range for the verbal and math sections of the SAT

The SAT ( ) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since its debut in 1926, its name and scoring have changed several times; originally called the Scholastic Aptitude Test, it was later called the Schol ...

is 660–750 and 660–750, respectively—numbers of only those submitting scores during the admissions process. The middle 50% ACT range is 30–33.

The April 17, 2008, edition of ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

'' noted Bowdoin in an article on university admissions: "So-called 'almost-Ivies' such as Bowdoin and Middlebury also saw record low admission rates this year (18% each). It is now as hard to get into Bowdoin, says the college's admissions director, as it was to get into Princeton in the 1970s." Many students apply for financial aid, and around 85% of those who apply to receive aid. Bowdoin is a need-blind

Need-blind admission is a term used in the United States denoting a college admission policy in which an institution does not consider an applicant's financial situation when deciding admission. This policy generally increases the proportion of a ...

and no-loans institution. While a significant portion of the student body hails from New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

—including nearly 25% from Massachusetts and 10% from Maine—recent classes have drawn from an increasingly national and international pool. The median family income of Bowdoin students is $195,900, with 57% of students coming from the top 10% of highest-earning families and 17.5% from the bottom 60%. Although Bowdoin once had a reputation for homogeneity (both ethnically and socioeconomically), a diversity campaign has increased the percentage of students of color in recent classes to more than 31%. In fact, admission of minorities goes back at least as far as John Brown Russwurm

John Brown Russwurm (October 1, 1799 – June 9, 1851) was an abolitionist, newspaper publisher, and colonizer of Liberia, where he moved from the United States. He was born in Jamaica to an English father and enslaved mother. As a child he t ...

1826, Bowdoin's first African-American college graduate and the third African-American graduate of any American college.

Academics

Course distribution requirements were abolished in the 1970s but were reinstated by a faculty majority vote in 1981 due to an initiative by oral communication and film professor Barbara Kaster. She insisted that distribution requirements would ensure students a more well-rounded education in a diversity of fields and therefore present them with more career possibilities. The requirements of at least two courses in each of the categories ofnatural sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

/ mathematics, social and behavioral sciences, humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at the t ...

/ fine arts, and foreign studies (including languages) took effect for the class of 1987 and have been gradually amended since then. Current requirements require one course each in natural sciences, quantitative reasoning, visual and performing arts, international perspectives, and exploring social differences. A small writing-intensive course, called a first-year seminar, is also required.

In 1990, the Bowdoin faculty voted to change the four-level grading system to the traditional A, B, C, D, and F system. The previous system, consisting of high honors, honors, pass, and fail, was devised primarily to de-emphasize the importance of grades and to reduce competition. In 2002, the faculty decided to change the grading system so that it incorporated plus and minus grades. In 2006, Bowdoin was named a "Top Producer of Fulbright Award

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

s for American Students" by the Institute of International Education.

Other notable Bowdoin faculty include (or have included): Edville Gerhardt Abbott, Charles Beitz

Charles R. Beitz (born 1949) is an American political theorist. He is Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton University, where he has been director of the University Center for Human Values and director of the Program in Political ...

, John Bisbee, Paul Chadbourne

Paul Ansel Chadbourne (October 21, 1823 – February 23, 1883) was an American educator and naturalist who served as President of University of Wisconsin from 1867 to 1870, and President of Williams College from 1872 until his resignation in 188 ...

, Thomas Cornell, Kristen R. Ghodsee

Kristen Rogheh Ghodsee (born April 26, 1970) is an American ethnographer and Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She is primarily known for her ethnographic work on post-Communist Bulgaria as well as ...

, Eddie Glaude

Eddie S. Glaude Jr. (born September 4, 1968) is an American academic. He is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, where he is also the Chair of the Center for African Amer ...

, Joseph E. Johnson, Richard Morgan, Elliott Schwartz

Elliott Shelling Schwartz (January 19, 1936 – December 7, 2016) was an American composer. A graduate of Columbia University, he was Beckwith Professor Emeritus of music at Bowdoin College joining the faculty in 1964. In 2006, the Library of ...

, Kenneth Chenault

Kenneth Irvine Chenault (born June 2, 1951) is an American business executive. He was the CEO and Chairman of American Express from 2001 until 2018. He is the third African American CEO of a Fortune 500 company.

Early life and education

Chen ...

, and Scott Sehon

Scott Robert Sehon (born 1963) is an American philosopher and a professor of philosophy at Bowdoin College. His primary work is in the fields of philosophy of mind, metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of action, and the free will debate. He is ...

.

Rankings

In the 2021 edition of the '' U.S. News & World Report'' rankings, Bowdoin was ranked tied for 6th best overall among liberal arts colleges in the United States, tied at 11th for "Best Undergraduate Teaching", 12th in "Best Value Schools", and tied at 29th for "Most Innovative". In the 2019 ''Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine owned by Integrated Whale Media Investments and the Forbes family. Published eight times a year, it features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. ''Forbes'' also r ...

'' college rankings, Bowdoin was ranked 26th overall among 650 universities, liberal arts colleges, and service academies and 6th among private liberal arts colleges.

Bowdoin College is accredited

Accreditation is the independent, third-party evaluation of a conformity assessment body (such as certification body, inspection body or laboratory) against recognised standards, conveying formal demonstration of its impartiality and competence to ...

by the New England Commission of Higher Education

The New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE) is a voluntary, peer-based, non-profit membership organization that performs peer evaluation and accreditation of public and private universities and colleges in the United States and other ...

.

Bowdoin was ranked first among 1,204 small colleges in the U.S. by Niche in 2017.

Based on students' SAT scores, Bowdoin is tied with Williams for 5th in Business Insider's smartest liberal arts colleges, with an average score of 1435 for math and critical reading combined. Among all colleges, it is tied with Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model us ...

, Carnegie Mellon

Carnegie may refer to:

People

*Carnegie (surname), including a list of people with the name

*Clan Carnegie, a lowland Scottish clan

Institutions Named for Andrew Carnegie

* Carnegie Building (Troy, New York), on the campus of Rensselaer Polyte ...

, and Williams for 22nd.

The college was ranked 5th in the country by ''Washington Monthly

''Washington Monthly'' is a bimonthly, nonprofit magazine of United States politics and government that is based in Washington, D.C. The magazine is known for its annual ranking of American colleges and universities, which serves as an alterna ...

'' in 2019 based on its contribution to the public good, as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service.

In 2006, ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' described Bowdoin as a " New Ivy", one of a number of liberal arts colleges and universities outside of the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight school ...

, and it has also been dubbed a " Hidden Ivy".

Student life

Princeton Review

The Princeton Review is an education services company providing tutoring, test preparation and admission resources for students. It was founded in 1981. and since that time has worked with over 400 million students. Services are delivered by 4,0 ...

'' in 2004, 2006, 2007, 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2016, with ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reporting: "If it weren't for the trays, and for the fact that most diners are under 25, you'd think it was a restaurant."

Bowdoin uses food from its organic garden in its two major dining halls, and every academic year begins with a lobster bake outside Farley Fieldhouse.

Recalling his days at Bowdoin in a recent interview, Professor Richard E. Morgan (class of 1959) described student life at the then-all-male school as "monastic" and noted that "the only things to do were either work or drink". This is corroborated by the '' Official Preppy Handbook,'' which in 1980 ranked Bowdoin the number two drinking school in the country, behind Dartmouth. These days, Morgan observed, the college offers a far broader array of recreational opportunities: "If we could have looked forward in time to Bowdoin's standard of living today, we would have been astounded."

Since abolishing Greek fraternities

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity ...

in the late 1990s, Bowdoin has switched to a system in which entering students are assigned a "college house" affiliation correlating with their first-year dormitory. While six houses were originally established following the construction of two new dorms, two were added effective in the fall of 2007, bringing the total to eight: Ladd, Baxter, Quinby, MacMillan, Howell, Helmreich, Reed, and Burnett. The college houses are physical buildings around campus that host parties and other events throughout the year. Those students who choose not to live in their affiliated house retain their affiliation and are considered members throughout their Bowdoin career. Before the fraternity system was abolished in the 1990s, all the Bowdoin fraternities were co-educational (except for one unrecognized sorority and two unrecognized all-male fraternities).

Bowdoin's chapter of Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

was founded in 1825. Those who have been inducted to the Maine chapter as undergraduates include Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

(1825), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

(1825), Robert E. Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is best known for, in Apri ...

(1877), Owen Brewster

Ralph Owen Brewster (February 22, 1888 – December 25, 1961) was an Politics of the United States, American politician from Maine. Brewster, a Republican Party (United States), Republican, served as the List of governors of Maine, 54th Governor ...

(1909), Harold Hitz Burton

Harold Hitz Burton (June 22, 1888 – October 28, 1964) was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Sta ...

(1909), Paul Douglas

Paul Howard Douglas (March 26, 1892 – September 24, 1976) was an American politician and Georgist economist. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Senator from Illinois for eighteen years, from 1949 to 1967. During his Senat ...

(1913), Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey (; June 23, 1894 – August 25, 1956) was an American sexologist, biologist, and professor of entomology and zoology who, in 1947, founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Insti ...

(1916), Thomas R. Pickering

Thomas Reeve "Tom" Pickering (born November 5, 1931) is a retired United States ambassador. Among his many diplomatic appointments, he served as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations from 1989 to 1992.

Early life and education

Born in Orange, ...

(1953), and Lawrence B. Lindsey (1976).

Clubs

The largest student group on campus is the Outing Club, which leads canoeing, kayaking, rafting, camping, and backpacking trips throughout Maine. One of the school's two historic rival literary societies, The Peucinian Society, has recently been revitalized from its previous form. The Peucinian Society was founded in 1805. This organization counts such people as

The largest student group on campus is the Outing Club, which leads canoeing, kayaking, rafting, camping, and backpacking trips throughout Maine. One of the school's two historic rival literary societies, The Peucinian Society, has recently been revitalized from its previous form. The Peucinian Society was founded in 1805. This organization counts such people as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (born Lawrence Joshua Chamberlain, September 8, 1828February 24, 1914) was an American college professor from Maine who volunteered during the American Civil War to join the Union Army. He became a highly respected a ...

amongst its former members. The other, the now-defunct Athenian Society, included Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

and Franklin Pierce as members. These literary and intellectual societies were the dominant groups on campus before they declined in popularity after the rise of Greek fraternities

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternity ...

.

Bowdoin competes in the Standard Platform League of RoboCup as the Northern Bites, where teams compete with five autonomous Aldebaran Nao robots. Bowdoin won the world championship in RoboCup 2007, beating Carnegie Mellon University, and finished 2nd in the 2015 US Open.

Media and publications

Bowdoin's student newspaper, ''The Bowdoin Orient

''The Bowdoin Orient'' is the student newspaper of Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, United States. Established in 1871, the ''Orient'' is the oldest continuously-published college weekly in the United States. It was named the second best tab ...

'', is the oldest continuously published college weekly in the United States. The Orient was named the second-best tabloid-sized college weekly at a Collegiate Associated Press conference in March 2007 and the best college newspaper in New England by the New England Society of News Editors in 2018.

The school's literary magazine, '' The Quill'', was published between 1897 and 2015. ''The Bowdoin Globalist'', an international news, culture, and politics magazine affiliated with the Global21 organization of college magazines, has been publishing since 2012. ''The Bowdoin Globalist'' transitioned to a digital-only platform in 2015 and changed its name to ''The Bowdoin Review''. The college's radio station, WBOR

WBOR (91.1 FM) is a radio station licensed to Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, United States. The station broadcasts from the basement of the Dudley Coe Building on the Bowdoin College campus. Programming consists of an eclectic mix of indie ...

, has been operating since the early 1940s. In 1999, ''The Bowdoin Cable Network'' was formed, producing a weekly newscast and several student-created shows per semester.

A cappella

Six a cappella groups are on campus. The Meddiebempsters and the Longfellows are all-male, Miscellania is all-female, BOKA and Ursus Verses are co-ed, and Bear Tones's singers are "female and treble voices". The Longfellows are the newest all-male group. Founded in 2004, they trace their roots to the historic class of 1825 at Bowdoin, which graduated Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In 2011, they won their quarterfinal of the International Collegiate Championship of A Cappella, advancing them to the semifinals as the only all-male group. The same year, they were in the final round of selection to be on NBC's "The Sing Off". In 2010 and again in 2013, they sang the national anthem at a Boston Celtics game. They have performed all over Maine and the Northeast. The Meddiebempsters are the oldest of Bowdoin's six a cappella groups. Founded in the spring of 1937, the Meddies performed inUSO

The United Service Organizations Inc. (USO) is an American nonprofit-charitable corporation that provides live entertainment, such as comedians, actors and musicians, social facilities, and other programs to members of the United States Armed F ...

shows after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

Miscellania is the oldest all-female a cappella group at Bowdoin College. Miscellania was founded in 1972 as the female counterpart to the Meddiebempsters, shortly after women were admitted to Bowdoin. Since then, Miscellania has grown to be a part of the tradition of a cappella at Bowdoin College. Distinguishable by their black dresses, Miscellania has performed all over Maine and the Northeast, as well as down the East Coast on longer tours, and Aruba.

Bear Tones, founded in 2016, is Bowdoin's most-recently formed a cappella group, and is open to male and female singers of all treble voices.

Environmental record

Bowdoin College signed onto the American College and University President's Climate Commitment in 2007. The college followed through with a carbon neutrality plan released in 2009, with 2020 as the target year for carbon neutrality. According to the plan, general improvements to Maine's electricity grid will account for 7% of carbon reductions, commuting improvements will account for 1%, and the purchase of renewable energy credits will account for 41%. The college intends to reduce its carbon emissions 28% by 2020, leaving the remaining 23% for new technologies and more renewable energy credits. The plan includes the construction of a solar thermal system, part of the "Thorne Solar Hot Water Project"; cogeneration in the central heating plant (for which Bowdoin received $400,000 in federal grants); lighting upgrades to all campus buildings; and modern monitoring systems of energy usage on campus. In 2017 the college was on track to meet the 28% own source reduction target, and efforts have continued in the areas of energy conservation, efficiency upgrades and transitioning to lower carbon fuel sources. Bowdoin's facilities are heated by an on-campus heating plant that burns natural gas. In February 2013, the college announced that 1.4% of its endowment is invested in the fossil fuel industry. The disclosure was in response to students' calls to divest these holdings. Between 2002 and 2008, Bowdoin College decreased its CO2 emissions by 40%. It achieved that reduction by switching from #6 to #2 oil in its heating plant, reducing the campus set heating point from 72 to 68 degrees, and by adhering to its own Green Design Standards in renovations. In addition, Bowdoin runs a single stream recycling program, and its dining services department has begun compostingfood waste

Food loss and waste is food that is not eaten. The causes of food waste or loss are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during production, processing, distribution, retail and food service sales, and consumption. Overall, about o ...

and unbleached paper napkins. Bowdoin received an overall "B−" grade for its sustainability efforts on the College Sustainability Report Card 2009 published by the Sustainable Endowments Institute.

In 2003, Bowdoin committed to achieving LEED-certification for all new campus buildings. The college has since completed construction on Osher and West residency halls, the Peter Buck Center for Health & Fitness, the Sidney J. Watson Arena, 216 Maine Street, and 52 Harpswell all of which have attained LEED, Silver LEED or Gold LEED certification. The new dorms partially use collected rainwater as part of an advanced flushing system.

Campus

Brunswick main campus

Bowdoin College's main campus in Brunswick ranges over an area of and includes 120 buildings, some of which date back to the 18th century. Prominent buildings on the campus include the college's oldest building,Massachusetts Hall Massachusetts Hall may refer to:

* Massachusetts Hall (Harvard University)

Massachusetts Hall is the oldest surviving building at Harvard College, the first institution of higher learning in the British colonies in America, and second oldest acad ...

, the Parker Cleaveland House, and the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. The campus has two museums. The Bowdoin College Museum of Art is located in the Walker Art Building, while the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum is situated in Hubbard Hall.

Other properties

The Schiller Coastal Studies Center is located south of Orr's Island inHarpswell, Maine

Harpswell is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States, within Casco Bay in the Gulf of Maine. The population was 5,031 at the 2020 census. Harpswell is composed of land contiguous with the rest of Cumberland County, called Harpswell ...

.

Bowdoin College operates the Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island

Kent Island is the largest island in the Chesapeake Bay and a historic place in Maryland. To the east, a narrow channel known as the Kent Narrows barely separates the island from the Delmarva Peninsula, and on the other side, the island is sep ...

in the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

.

Athletics

Organized athletics at Bowdoin began in 1828 with a gymnastics program established by the "father of athletics in Maine," John Neal. In the proceeding years, Neal agitated for more programs, and himself taught

Organized athletics at Bowdoin began in 1828 with a gymnastics program established by the "father of athletics in Maine," John Neal. In the proceeding years, Neal agitated for more programs, and himself taught bowling

Bowling is a target sport and recreational activity in which a player rolls a ball toward pins (in pin bowling) or another target (in target bowling). The term ''bowling'' usually refers to pin bowling (most commonly ten-pin bowling), thou ...

, boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermine ...

, and other sports.

Bowdoin College teams are known as the Polar Bears. They compete as a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges ...

(NCAA) Division III

In sport, the Third Division, also called Division 3, Division Three, or Division III, is often the third-highest division of a league, and will often have promotion and relegation with divisions above and below.

Association football

*Belgian Thir ...

level, primarily competing in the New England Small College Athletic Conference

The New England Small Collegiate Athletic Conference (NESCAC) is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising sports teams from eleven highly selective liberal arts institutions of higher education in the Northeastern United States. ...

(NESCAC), of which they were a founding member in 1971.

The mascot for all Bowdoin College athletic teams is the Polar bear, generally referred to in the plural, i.e., "The Polar Bears." The school colors are black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

and white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

. The fight song, ''Forward The White'', was composed by Kenneth A. Robinson, class of 1914.

The college's rowing club competes in the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Chase Regatta

The Colby–Bates–Bowdoin Chase Regatta (often abbreviated CBB Chase or the "Chase Regatta") is an annual rowing regatta between the men's and women's heavyweight varsity and club rowing crews of Colby, Bates, and Bowdoin College. The colleges h ...

annually. The field hockey team are four-time NCAA Division III National Champions; winning the title in 2007 (defeating Middlebury College), 2008 (defeating Tufts University

Tufts University is a private research university on the border of Medford and Somerville, Massachusetts. It was founded in 1852 as Tufts College by Christian universalists who sought to provide a nonsectarian institution of higher learning. ...

), 2010 (defeating Messiah College

Messiah University is a private interdenominational evangelical Christian university in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.

History

The school was founded as Messiah Bible School and Missionary Training Home in 1909 by the Brethren in Christ Church. ...

), and 2013 (defeating Salisbury University

Salisbury University is a public university in Salisbury, Maryland. Founded in 1925, Salisbury is a member of the University System of Maryland, with a fall 2016 enrollment of 8,748.

Salisbury University offers 42 distinct undergraduate and 14 ...

). The men's tennis team won the 2016 NCAA Division III Championship after defeating Emory University in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Principal athletic facilities include Whittier Field

Whittier Field is the outdoor stadium of Bowdoin College. Located in Brunswick, Maine, it is the field for Bowdoin football, Bowdoin outdoor track and field, and the Maine Distance Festival. The Whittier Field Athletic Complex was added to the Nati ...

(capacity: 9,000), Morrell Gymnasium (1,500), Sidney J. Watson Arena (2,300), Pickard Fields, and the Buck Center for Health and Wellness. Bowdoin students compete in 30 varsity sports and several club and intramural teams.

Notable alumni

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

File:Nathaniel Hawthorne by Brady, 1860-64.jpg, Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

, novelist

File:Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1868.jpg, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

, poet

File:Robert Peary self-portrait, 1909.jpg, Robert Peary, explorer, who claims to be the first person to reach the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

File:Re publica 2015 - Tag 1 (17195424118) (cropped).jpg, Reed Hastings

Wilmot Reed Hastings Jr. (born October 8, 1960) is an American billionaire businessman. He is the co-founder, chairman, and co-chief executive officer (CEO) of Netflix, and sits on a number of boards and non-profit organizations. A former member ...

, co-founder of Netflix

Netflix, Inc. is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service and production company based in Los Gatos, California. Founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph in Scotts Valley, California, it offers a fi ...

File:Hon. William P. Fessenden, Maine - NARA - 529980.jpg, William P. Fessenden, former U.S. Secretary of the Treasuery

File:Paul Adelstein 2008.jpg, Paul Adelstein

Paul Adelstein (born April 29, 1969) is an American actor and writer, known for the role of Agent Paul Kellerman in the Fox television series ''Prison Break'' and his role as pediatrician Cooper Freedman in the ABC medical drama '' Private Prac ...

, actor

File:William Cohen, official portrait (cropped).jpg, William Cohen

William Sebastian Cohen (born August 28, 1940) is an American lawyer, author, and politician from the U.S. state of Maine. A Republican, Cohen served as both a member of the United States House of Representatives (1973–1979) and Senate (1979� ...

, 20th U.S. Secretary of Defense and former U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

File:Joshua Chamberlain - Brady-Handy.jpg, Joshua Chamberlain

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (born Lawrence Joshua Chamberlain, September 8, 1828February 24, 1914) was an American college professor from Maine who volunteered during the American Civil War to join the Union Army. He became a highly respected and ...

, Brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

File:Oliver Otis Howard.jpg, Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men agains ...

, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

File:CJ Fuller.tif, Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his ...

, 8th Chief Justice of the United States

File:Pat Meehan, Official Portrait, 112th Congress.jpg, Pat Meehan

Patrick Leo Meehan (born October 20, 1955) is a former American Republican Party politician and federal prosecutor from Pennsylvania who represented parts of Delaware, Chester, Montgomery, Berks, and Lancaster counties in the United States Hou ...

, former U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

File:Governor Lawrence B Lindsey 140501.jpg, Lawrence B. Lindsey, Member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, commonly known as the Federal Reserve Board, is the main governing body of the Federal Reserve System. It is charged with overseeing the Federal Reserve Banks and with helping implement the m ...

File:George Mitchell in Tel Aviv July 26, 2009.jpg, George J. Mitchell

George John Mitchell Jr. (born August 20, 1933) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. A leading member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Maine from 1980 to 1995, and as Senate Majority Leader from 19 ...

, former Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding t ...

File:Mayor Ed Lee Headshot Closeup.jpg, Ed Lee

Edwin Mah Lee (Chinese: 李孟賢; May 5, 1952 – December 12, 2017) was an American politician and attorney who served as the 43rd Mayor of San Francisco from 2011 until his death. He was the first Asian American to hold the office.

Born in ...

, former Mayor of San Francisco

The mayor of the City and County of San Francisco is the head of the executive branch of the San Francisco city and county government. The officeholder has the duty to enforce city laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills passed by ...

File:Harold Burton.jpg, Harold Hitz Burton

Harold Hitz Burton (June 22, 1888 – October 28, 1964) was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Sta ...

, former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

File:Thomas Brackett Reed - Brady-Handy.jpg, Thomas Brackett Reed

Thomas Brackett Reed (October 18, 1839 – December 7, 1902) was an American politician from the state of Maine. A member of the Republican Party, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives 12 times, first in 1876, and served ...

, former Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

File:Picture of Augustus Stinchfield.jpg, Augustus Stinchfield

Augustus W. Stinchfield (December 21, 1842 – March 15, 1917) was an American physician and one of the co-founders—along with Drs. Charles Horace Mayo, William James Mayo, Christopher Graham, E. Starr Judd, Henry Stanley Plummer, Melvin ...

, co-founder of Mayo Clinic

File:Alfred Kinsey 1955.jpg, Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey (; June 23, 1894 – August 25, 1956) was an American sexologist, biologist, and professor of entomology and zoology who, in 1947, founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Insti ...

, biologist and sexologist

William Pitt Fessenden

William Pitt Fessenden (October 16, 1806September 8, 1869) was an American politician from the U.S. state of Maine. Fessenden was a Whig (later a Republican) and member of the Fessenden political family. He served in the United States House o ...

(1824)

* U.S. President Franklin Pierce (1824)

* Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tran ...

(1825)

* Novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

(1825)

* Journalist and Republic of Maryland

The Republic of Maryland (also known variously as the Independent State of Maryland, Maryland-in-Africa, and Maryland in Liberia) was a country in West Africa that existed from 1834 to 1857, when it was merged into what is now Liberia. The area ...

governor John Brown Russwurm

John Brown Russwurm (October 1, 1799 – June 9, 1851) was an abolitionist, newspaper publisher, and colonizer of Liberia, where he moved from the United States. He was born in Jamaica to an English father and enslaved mother. As a child he t ...

(1826)

* Medical missionary to the Batticotta Seminary

The Batticotta Seminary was an educational institute founded by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM)'s American Ceylon Mission at Vaddukodai, in the Jaffna Peninsula north Sri Lanka in 1823. It was founded as part of ...

, Nathan Ward

Nathan Ward (born December 8, 1981) is a Canadians, Canadian former professional ice hockey player.

Career

Ward's senior level career began with his move into the NCAA for Lake Superior State University (LSSU). Ward established himself quickly ...

* Mayor of Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

(1867–1869) and founding Regent of the University of California

The Regents of the University of California (also referred to as the Board of Regents to distinguish the board from the corporation it governs of the same name) is the governing board of the University of California (UC), a state university sy ...

(1868–1874), Samuel Merritt

Dr Samuel Merritt (1822–1890) was a physician and the 13th mayor of Oakland, California, from 1867–1869. He was a founding Regent of the University of California, 1868-1874. He was also a shipmaster and a very successful businessman; he di ...

(1844)

* Joshua Young

Joshua Young (September 23, 1823 – February 7, 1904) was an abolitionist Congregational Unitarian minister who crossed paths with many famous people of the mid-19th century. He received national publicity, and lost his pulpit (job) for presidi ...

, Unitarian minister, presided over funeral of John Brown (1845)

* Civil War general Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (born Lawrence Joshua Chamberlain, September 8, 1828February 24, 1914) was an American college professor from Maine who volunteered during the American Civil War to join the Union Army. He became a highly respected a ...

(1852)

* Philosopher, minister, and academic Charles Carroll Everett (1850)

* Civil War general Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men agains ...

(1850)

* Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his ...

(1853)

* U.S. Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed

Thomas Brackett Reed (October 18, 1839 – December 7, 1902) was an American politician from the state of Maine. A member of the Republican Party, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives 12 times, first in 1876, and served ...

(1860)

* Civil War general Thomas W. Hyde, Medal of Honor recipient, author, founder of Bath Iron Works

Bath Iron Works (BIW) is a major United States shipyard located on the Kennebec River in Bath, Maine, founded in 1884 as Bath Iron Works, Limited. Since 1995, Bath Iron Works has been a subsidiary of General Dynamics. It is the fifth-largest ...

(1861)

* Mayo Clinic co-founder Dr. Augustus Stinchfield

Augustus W. Stinchfield (December 21, 1842 – March 15, 1917) was an American physician and one of the co-founders—along with Drs. Charles Horace Mayo, William James Mayo, Christopher Graham, E. Starr Judd, Henry Stanley Plummer, Melvin ...

(1868)

* Physicist Edwin Hall

Edwin Herbert Hall (November 7, 1855 – November 20, 1938) was an American physicist, who discovered the eponymous Hall effect. Hall conducted thermoelectric research and also wrote numerous physics textbooks and laboratory manuals.

Biograp ...

(1875)

* Freelan Oscar Stanley

Freelan Oscar Stanley (June 1, 1849 – October 2, 1940) was an American inventor, entrepreneur, hotelier, and architect. He made his fortune in the manufacture of photographic plates but is best remembered as the co-founder, with his brother Fra ...

, inventor of the Stanley Steamer

The Stanley Motor Carriage Company was an American manufacturer of steam cars; it operated from 1902 to 1924. The cars made by the company were colloquially called Stanley Steamers, although several different models were produced.

Early history ...

, and builder of the Stanley Hotel (1877)

* Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary (1877)

* Cravath, Swaine & Moore Presiding Partner Hoyt Augustus Moore (1895)

* Gold mine owner, entrepreneur, investor and philanthropist Sir Harry Oakes

Sir Harry Oakes, 1st Baronet (23 December 1874 – 7 July 1943) was a British gold mine owner, entrepreneur, investor and philanthropist. He earned his fortune in Canada and moved to the Bahamas in the 1930s for tax purposes. Though American by b ...

(1896)

* Chairman and, later, Secretary-General of the Shanghai Municipal Council

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

, Stirling Fessenden (1896)

* Arctic explorer Donald B. MacMillan

Donald Baxter MacMillan (November 10, 1874 – September 7, 1970) was an American explorer, sailor, researcher and lecturer who made over 30 expeditions to the Arctic during his 46-year career.

He pioneered the use of radios, airplanes, an ...

(1898)

* Business leader and President, Manufacturers Trust Company Harvey Dow Gibson

Harvey Dow Gibson (March 12, 1882 – September 11, 1950) was an American businessman.

Early life

Harvey Dow Gibson was born on March 12, 1882, at North Conway in Carroll County, New Hampshire. He was the son of James Lewis Gibson (1855–1933) ...

(1902)

* US Senator Paul H. Douglas (1913)

* Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Robert P. T. Coffin

Robert Peter Tristram Coffin (March 18, 1892 – January 20, 1955) was an American poet, educator, writer, editor and literary critic. Awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1936, he was the Poetry editor for ''Yankee'' magazine.

Early life ...

(1915)

* Sex researcher Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey (; June 23, 1894 – August 25, 1956) was an American sexologist, biologist, and professor of entomology and zoology who, in 1947, founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Insti ...

(1916)

* Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Hodding Carter

William Hodding Carter, II (February 3, 1907 – April 4, 1972), was a Southern U.S. progressive journalist and author. Among other distinctions in his career, Carter was a Nieman Fellow and Pulitzer Prize winner. He died in Greenville, Missis ...

(1927)

* Film and television actor Gary Merrill

Gary Fred Merrill (August 2, 1915 – March 5, 1990) was an American film and television actor whose credits included more than 50 feature films, a half-dozen mostly short-lived TV series, and dozens of television guest appearances. He starr ...

(1937)

* Congressional Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

recipient Everett P. Pope, who displayed conspicuous gallantry during the Battle of Peleliu

The Battle of Peleliu, codenamed Operation Stalemate II by the US military, was fought between the United States and Japan during the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign of World War II, from September 15 to November 27, 1944, on the island of ...

(1941)

* Recipient of two Silver Stars, Andrew Haldane

Andrew Allison Haldane (August 22, 1917 – October 12, 1944) was an officer in the United States Marine Corps in the Pacific theatre during World War II. He was killed in action during the Battle of Peleliu.

Haldane is portrayed by actor Scot ...

, who was killed in action during the Battle of Peleliu