Bourbon Democrats on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the

The nickname "Bourbon Democrat" was first used as a pun, referring to

The nickname "Bourbon Democrat" was first used as a pun, referring to

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, e ...

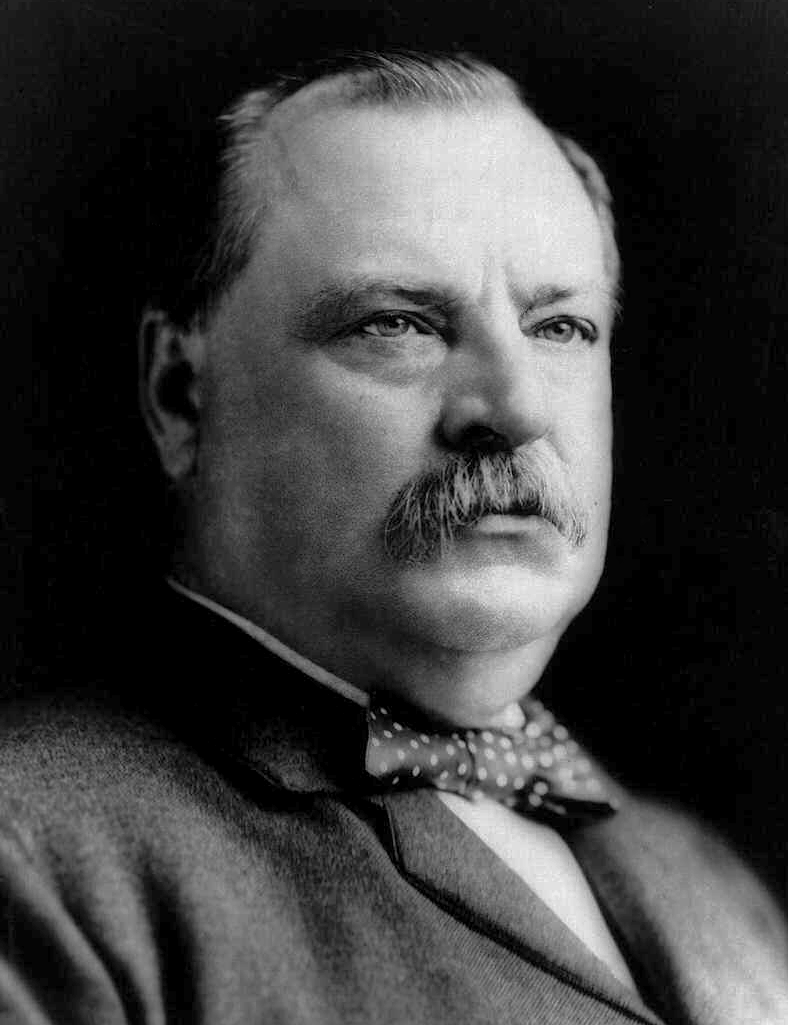

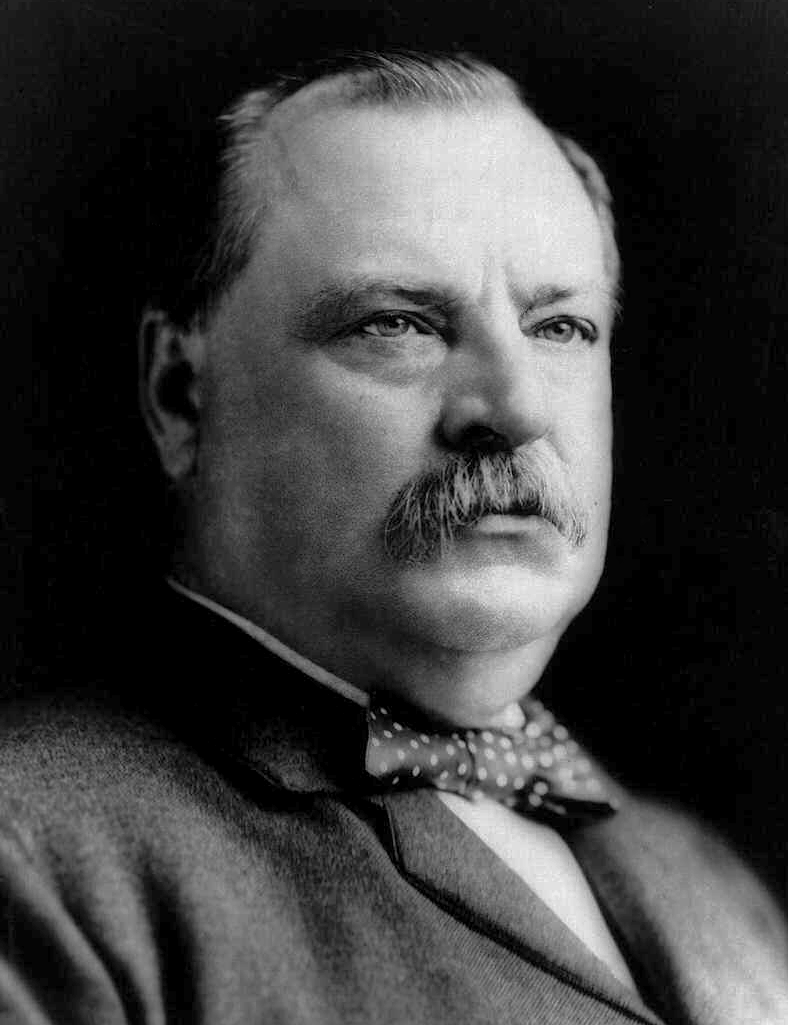

, especially those who supported presidential candidates Charles O'Conor in 1872, Samuel J. Tilden in 1876, President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

in 1884, 1888, and 1892 and Alton B. Parker in 1904.

After 1904, the Bourbons faded away. Southerner Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

made a deal in 1912 with the leading opponent of the Bourbons, William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

: Bryan endorsed Wilson for the Democratic nomination and Wilson named Bryan Secretary of State. Bourbon Democrats were promoters of a form of ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

'' capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

which included opposition to the high-tariff protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulation ...

that the Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

were then advocating as well as fiscal discipline. They represented business interests, generally supporting the goals of banking and railroads, but opposed to subsidies for them and were unwilling to protect them from competition. They opposed American imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conquest ...

and overseas expansion, fought for the gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

against bimetallism, and promoted what they called "hard" and "sound" money. Strong supporters of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and ...

and reform movements such as the Civil Service Reform and opponents of the corrupt city boss

In politics, a boss is a person who controls a faction or local branch of a political party. They do not necessarily hold public office themselves; most historical bosses did not, at least during the times of their greatest influence. Numerous o ...

es, Bourbons led the fight against the Tweed Ring

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany H ...

. The anti-corruption theme earned the votes of many Republican Mugwumps in 1884.

The term "Bourbon Democrats" was never used by the Bourbon Democrats themselves. It was not the name of any specific or formal group and no one running for office ever ran on a Bourbon Democrat ticket. The term "Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by ...

"—Bourbon is a Southern drink—was mostly used disparagingly by critics complaining of viewpoints they saw as old-fashioned.Hans Sperber and Travis Trittschuh. ''American Political Terms: An Historical Dictionary.'' Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1962. A number of splinter Democratic parties, such as the Straight-Out Democratic Party (1872) and the National Democratic Party (1896), that actually ran candidates, fall under the more general label of Bourbon Democrats.

Factional history

Origins of the term

The nickname "Bourbon Democrat" was first used as a pun, referring to

The nickname "Bourbon Democrat" was first used as a pun, referring to bourbon whiskey

Bourbon () is a type of barrel-aged American whiskey made primarily from corn. The name derives from the French Bourbon dynasty, although the precise source of inspiration is uncertain; contenders include Bourbon County in Kentucky and Bourbon ...

from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virgini ...

and even more to the Bourbon Dynasty

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, memb ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, which was overthrown in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, but returned to power in 1815 to rule in a reactionary fashion until its overthrow in the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

of 1830. A cadet Bourbon branch, the House of Orléans

The 4th House of Orléans (french: Maison d'Orléans), sometimes called the House of Bourbon-Orléans (french: link=no, Maison de Bourbon-Orléans) to distinguish it, is the fourth holder of a surname previously used by several branches of the R ...

, then ruled France for 18 years (1830–1848), until it too was overthrown in the February Revolution. Other branches of the House of Bourbon ruled Spain from 1700 and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily) from 1759. The latter was overthrown in 1861 when Italian troops under the command of Giuseppe Garibaldi overthrew Francis II, a major advance for the Italian Risorgimento. Spain's Queen Isabella II was overthrown in 1868 when liberal democrats seized power in the Glorious Revolution. Isabella's son returned to take the throne as King Alfonso XII six years later. A widely quoted aphorism at the time had it that the Bourbons "have learnt nothing, and forgotten nothing." During Reconstruction, the term "Bourbon" would have had the connotation of a retrogressive, reactionary dynasty out of step with the modern world.

The term was occasionally used in the 1860s and 1870s to refer to conservative Democrats (both North and South) who still held the ideas of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

and Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame a ...

and in the 1870s to refer to the regimes set up in the South by Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

as a conservative reaction against Reconstruction.

Gold Democrats and William Jennings Bryan

The electoral system elevated Bourbon Democrat leaderGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

to the office of President both in 1884 and in 1892, but the support for the movement declined considerably in the wake of the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pre ...

. President Cleveland, a staunch believer in the gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, refused to inflate the money supply with silver, thus alienating the agrarian populist wing of the Democratic Party.H. Wayne Morgan, ''From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896'', Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University, 1969; pp. 449–459.

The delegates at the 1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36, Br ...

quickly turned against the policies of Cleveland and those advocated by the Bourbon Democrats, favoring bimetallism as a way out of the depression. Nebraska Congressman William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

now took the stage as the great opponent of the Bourbon Democrats. Harnessing the energy of an agrarian insurgency with his famous Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported "free silver" (i.e. bimet ...

, Congressman Bryan soon became the Democratic nominee for president in the 1896 election.

Some of the Bourbons sat out the 1896 election or tacitly supported William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

, the Republican nominee whereas others set up the third-party ticket of the National Democratic Party led by John M. Palmer, a former Governor of Illinois. These bolters, called "gold Democrats", mostly returned to the Democratic Party by 1900 or by 1904 at the latest. Bryan demonstrated his hold on the party by winning the 1900 and 1908 Democratic nominations as well. In 1904, a Bourbon, Alton B. Parker, won the nomination and lost in the presidential race as did Bryan every time.

William L. Wilson, President Cleveland's Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsibl ...

, confided in his diary that he opposed Bryan on moral and ideological as well as party grounds. Wilson had begun his public service convinced that special interests had too much control over Congress and his unsuccessful tariff fight had burned this conviction deeper. He feared the triumph of free silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

would bring class legislation, paternalism

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good. Paternalism can also imply that the behavior is against or regardless of the will of a person, or also that the behavior expres ...

and selfishness feeding upon national bounty as surely as did protection. Moreover, he saw the proposed unlimited coinage of silver at a ratio of 16 to 1 to gold as morally wrong, "involving as it does the attempt to call 50 cents a dollar and make it legal tender for dollar debts". Wilson regarded populism

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develope ...

as "the product of protection founded on the idea that Government can and therefore Government ought to make people prosperous".

Decline

The nomination of Alton Parker in 1904 gave a victory of sorts to pro-gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

Democrats, but it was a fleeting one. The old classical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, econ ...

ideals had lost their distinctiveness and appeal. By World War I, the key elder statesman in the movement John M. Palmer—as well as Simon Bolivar Buckner

Simon Bolivar Buckner ( ; April 1, 1823 – January 8, 1914) was an American soldier, Confederate combatant, and politician. He fought in the United States Army in the Mexican–American War. He later fought in the Confederate States Army ...

, William F. Vilas

William Freeman Vilas (July 9, 1840August 27, 1908) was an American lawyer, politician, and United States Senator. In the U.S. Senate, he represented the state of Wisconsin for one term, from 1891 to 1897. As a prominent Bourbon Democrat, he wa ...

and Edward Atkinson—had died. During the 20th century, classical liberal ideas never influenced a major political party as much as they influenced the Democrats in the early 1890s.

State histories

West Virginia

West Virginia was formed in 1863 after Unionists from northwestern Virginia establish theRestored Government of Virginia

The Restored (or Reorganized) Government of Virginia was the Unionist government of Virginia during the American Civil War (1861–1865) in opposition to the government which had approved Virginia's seceding from the United States and join ...

. It remained in Republican control until the passing of the Flick Amendment The Flick Amendment was an 1871 Republican-initiated amendment to the West Virginia State Constitution that restored state rights to former Confederates and African-Americans who had been barred from voting and holding office in West Virginia follo ...

in 1871 returned states rights to West Virginians who had supported the defunct Confederacy. A Democratic push led to a reformatting of the West Virginia State Constitution that resulted in more power to the Democratic Party. In 1877, Henry M. Mathews, as a Bourbon, was elected governor of the state and the Bourbons held onto power in the state until the 1893 election of Republican George W. Atkinson.

Louisiana

In the spring of 1896, mayor John Fitzpatrick ofNew Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

"Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900"

''Independent Review'' 4 (Spring 2000), 555–575. * Allen J. Going, ''Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874–1890'', Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1951. * Roger L. Hart, ''Redeemers, Bourbons and Populists: Tennessee, 1870–1896'', Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1975. * Allan Nevins. ''Grover Cleveland A study in courage'' (1938). * C. Vann Woodward, ''Origins of the New South, 1877–1913'', Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1951. *

''Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party''"> ''Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party''

(1896). This was the campaign textbook of the Gold Democrats and is filled with speeches and arguments. * Encyclopedia of Alabama

"Alabama Bourbons"

{{Liberalism US footer 1872 establishments in the United States 1912 disestablishments in the United States 1896 elections in the United States Anti-imperialism Civil service reform in the United States Classical liberalism Conservatism in the United States Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Liberalism in the United States Progressive Era in the United States Bourbon Democrats

Walter C. Flower

Walter Chew Flower (1850-1900) was the 44th Mayor of New Orleans (April 27, 1896 – May 7, 1900). He was one of the participants and killers in the March 14, 1891 New Orleans lynchings

The March 14, 1891, New Orleans lynchings were the mur ...

. However, Fitzpatrick and his associates quickly regrouped, organizing themselves on December 29 into the Choctaw Club, which soon received considerable patronage from Louisiana governor and Fitzpatrick ally Murphy Foster. Fitzpatrick, a power at the 1898 Louisiana Constitutional Convention, was instrumental in exempting immigrants from the new educational and property requirements designed to disenfranchise blacks. In 1899, he managed the successful mayoral campaign of Bourbon candidate Paul Capdevielle.

Mississippi

Mississippi in 1877–1902 was politically controlled by the conservative whites, called "Bourbons" by their critics. The Bourbons represented the planters, landowners and merchants and used coercion and cash to control enough black votes to control the Democratic Party conventions and thus state government. Elected to the House of Representatives in 1885 and serving until 1901, Mississippi DemocratThomas C. Catchings

Thomas Clendinen Catchings (January 11, 1847 – December 24, 1927) was a U.S. Representative from Mississippi.

Early life and education

Thomas Clendenin Catchings was born January 11, 1847, at "Fleetwood" in Hinds County, Mississippi, to Dr ...

participated in the politics of both presidential terms of Grover Cleveland, particularly the free silver controversy and the agrarian discontent that culminated in populism. As a "gold bug" supporter of sound money, he found himself defending Cleveland from attacks of silverite Mississippians over the 1893 repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and other of Cleveland's actions unpopular in the South. Caught in the middle between his loyalty to Cleveland and the Southern Democrat silverites, Catchings continued as a sound money legislative leader for the minority in Congress while hoping that Mississippi Democrats would return to the conservative philosophical doctrines of the original Bourbon Democrats in the South.Leonard Schlup, "Bourbon Democrat: Thomas C. Catchings and the Repudiation of Silver Monometallism", ''Journal of Mississippi History'', vol. 57, no. 3 (1995) pp. 207–223.

Prominent Bourbon Democrats

See also

*Blue Dog Coalition

The Blue Dog Coalition (commonly known as the Blue Dogs or Blue Dog Democrats) is a Congressional caucus, caucus in the United States House of Representatives comprising centrist members from the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Par ...

* Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, e ...

* Conservative Democrat

In American politics, a conservative Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with conservative political views, or with views that are conservative compared to the positions taken by other members of the Democratic Party. Traditionally, co ...

* History of the United States Democratic Party

The Democratic Party is one of the two major political parties of the United States political system and the oldest existing political party in that country founded in the 1830s and 1840s.

It is also the oldest voter-based political party in t ...

* Libertarian Democrat

In American politics, a libertarian Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with political views that are relatively libertarian compared to the views of the national party.

While other factions of the Democratic Party, such as the Blue D ...

* Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats with ...

Footnotes

Further reading

* David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito"Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900"

''Independent Review'' 4 (Spring 2000), 555–575. * Allen J. Going, ''Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874–1890'', Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1951. * Roger L. Hart, ''Redeemers, Bourbons and Populists: Tennessee, 1870–1896'', Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1975. * Allan Nevins. ''Grover Cleveland A study in courage'' (1938). * C. Vann Woodward, ''Origins of the New South, 1877–1913'', Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1951. *

William Ivy Hair

William Ivy Hair (19301992) was an American historian and the Fuller E. Callaway Professor of Southern History at Georgia College in Milledgeville, Georgia.

Life Early life and education

William Ivy Hair was born on November 19, 1930, in Monroe, ...

, ''Bourbonism and Agrarian Protest: Louisiana Politics, 1877-1900'', Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Primary sources

* Allan Nevins (ed.), ''The Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908'', Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1933. * William L. Wilson, ''The Cabinet Diary of William L. Wilson, 1896–1897'', Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1957. * Democratic Party National Committee''Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party''"> ''Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party''

(1896). This was the campaign textbook of the Gold Democrats and is filled with speeches and arguments. * Encyclopedia of Alabama

"Alabama Bourbons"

{{Liberalism US footer 1872 establishments in the United States 1912 disestablishments in the United States 1896 elections in the United States Anti-imperialism Civil service reform in the United States Classical liberalism Conservatism in the United States Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Liberalism in the United States Progressive Era in the United States Bourbon Democrats