bored tunnel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

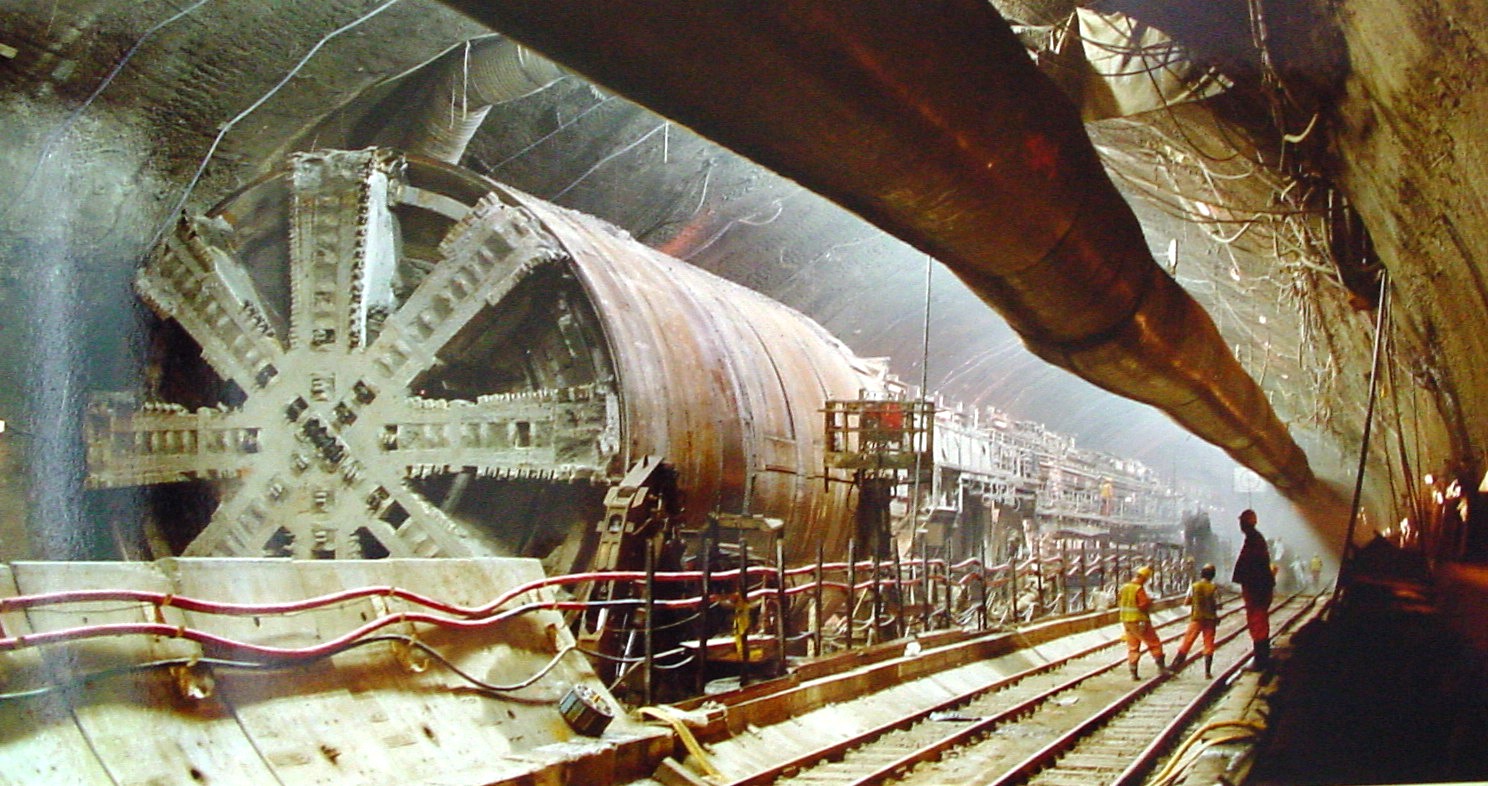

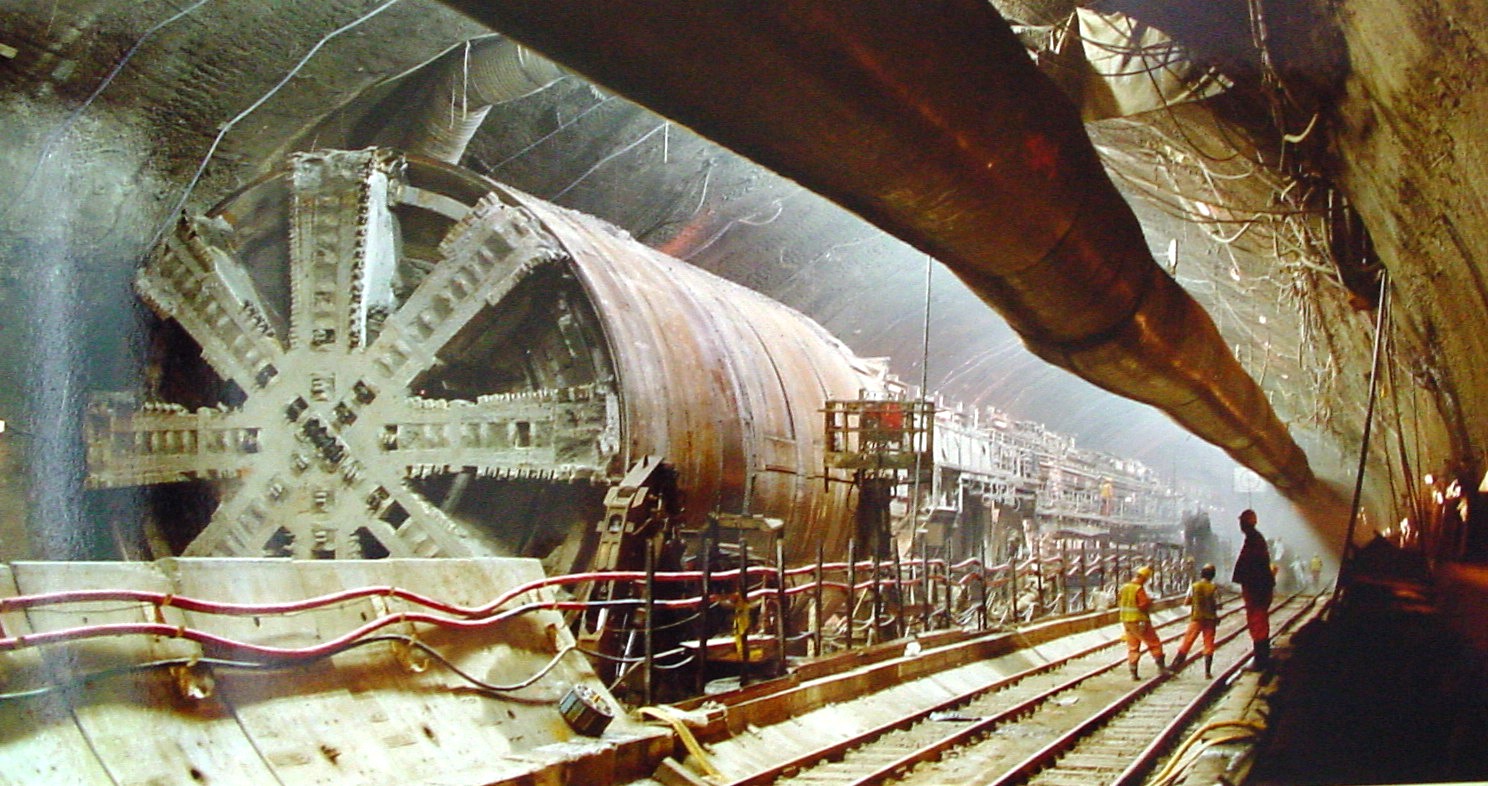

A tunnel boring machine (TBM), also known as a "mole", is a machine used to excavate tunnels with a circular cross section through a variety of soil and

A tunnel boring machine (TBM), also known as a "mole", is a machine used to excavate tunnels with a circular cross section through a variety of soil and

The first successful tunnelling shield was developed by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel to excavate the Thames Tunnel in 1825. However, this was only the invention of the shield concept and did not involve the construction of a complete tunnel boring machine, the digging still having to be accomplished by the then standard excavation methods.

The first boring machine reported to have been built was

The first successful tunnelling shield was developed by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel to excavate the Thames Tunnel in 1825. However, this was only the invention of the shield concept and did not involve the construction of a complete tunnel boring machine, the digging still having to be accomplished by the then standard excavation methods.

The first boring machine reported to have been built was

In the United States, the first boring machine to have been built was used in 1853 during the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in northwest Massachusetts. Made of cast iron, it was known as ''Wilson's Patented Stone-Cutting Machine'', after inventor Charles Wilson. It drilled 10 feet into the rock before breaking down. (The tunnel was eventually completed more than 20 years later, and as with the Fréjus Rail Tunnel, by using less ambitious methods.) Wilson's machine anticipated modern TBMs in the sense that it employed cutting discs, like those of a disc harrow, which were attached to the rotating head of the machine. In contrast to traditional chiseling or drilling and blasting, this innovative method of removing rock relied on simple metal wheels to apply a transient high pressure that fractured the rock. In 1853, the American Ebenezer Talbot also patented a TBM that employed Wilson's cutting discs, although they were mounted on rotating arms, which in turn were mounted on a rotating plate. In the 1870s, John D. Brunton of England built a machine employing cutting discs that were mounted eccentrically on rotating plates, which in turn were mounted eccentrically on a rotating plate, so that the cutting discs would travel over almost all of the rock face that was to be removed. The first TBM that tunneled a substantial distance was invented in 1863 and improved in 1875 by British Army officer Major Frederick Edward Blackett Beaumont (1833–1895); Beaumont's machine was further improved in 1880 by British Army officer Major Thomas English (1843–1935). In 1875, the French National Assembly approved the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel and the British Parliament supported a trial run using English's TBM. Its cutting head consisted of a conical drill bit behind which were a pair of opposing arms on which were mounted cutting discs. From June 1882 to March 1883, the machine tunneled, through chalk, a total of 1,840 m (6,036 ft). A French engineer, Alexandre Lavalley, who was also a Suez Canal contractor, used a similar machine to drill 1,669 m (5,476 ft) from Sangatte on the French side. However, despite this success, the cross-Channel tunnel project was abandoned in 1883 after the British military raised fears that the tunnel might be used as an invasion route. Nevertheless, in 1883, this TBM was used to bore a railway ventilation tunnel — 7 feet (2.1 m) in diameter and 6,750 feet (2 km) long — between Birkenhead and Liverpool, England, through sandstone under the Mersey River. During the late 19th and early 20th century, inventors continued to design, build, and test TBMs in response to the need for tunnels for railroads, subways, sewers, water supplies, etc. TBMs employing rotating arrays of drills or hammers were patented. TBMs that resembled giant hole saws were proposed. Other TBMs consisted of a rotating drum with metal tines on its outer surface, or a rotating circular plate covered with teeth, or revolving belts covered with metal teeth. However, these TBMs proved expensive, cumbersome, and unable to excavate hard rock; interest in TBMs therefore declined. Nevertheless, TBM development continued in potash and coal mines, where the rock was softer. A TBM with a bore diameter of was manufactured by The Robbins Company for Canada's

In hard rock, either shielded or open-type TBMs can be used. Hard rock TBMs cut rock with discs mounted in the cutter head. The disc cutters create compressive stress fractures in the rock, cracking chips from the tunnel face. The excavated rock (muck) is transferred through openings in the cutter head to a belt conveyor that carries it through the machine to a system of conveyors or muck cars.

Open-type TBMs have no shield, leaving the area behind the cutter head open for rock support. To advance, the machine uses a gripper system that pushes against the tunnel walls. Machines such as a Wirth machine can be steered only while ungripped. Other machines can be continuously steered. When gripped, the machine pushes forward. At the end of a cycle, the rear legs are lowered, while the grippers and propel cylinders are retracted and the machine advances. The grippers then reengage and the rear legs lift for the next boring cycle.

Open-type, or Main Beam machines do not install concrete segments behind. Instead, the rock is held up using ground support methods such as ring beams, rock bolts, shotcrete, steel straps, ring steel and wire mesh.

In fractured rock, shielded TBMs can be used. They erect concrete segments behind the machine to support tunnel walls. Double Shield TBMs have two modes; in stable ground they grip the tunnel walls to advance. In unstable, fractured ground, the thrust is shifted to thrust cylinders that push against the tunnel segments behind the machine. This keeps the thrust forces from impacting fragile tunnel walls. Single Shield TBMs operate in the same way, but are used only in fractured ground, as they can only push against concrete segments.

In hard rock, either shielded or open-type TBMs can be used. Hard rock TBMs cut rock with discs mounted in the cutter head. The disc cutters create compressive stress fractures in the rock, cracking chips from the tunnel face. The excavated rock (muck) is transferred through openings in the cutter head to a belt conveyor that carries it through the machine to a system of conveyors or muck cars.

Open-type TBMs have no shield, leaving the area behind the cutter head open for rock support. To advance, the machine uses a gripper system that pushes against the tunnel walls. Machines such as a Wirth machine can be steered only while ungripped. Other machines can be continuously steered. When gripped, the machine pushes forward. At the end of a cycle, the rear legs are lowered, while the grippers and propel cylinders are retracted and the machine advances. The grippers then reengage and the rear legs lift for the next boring cycle.

Open-type, or Main Beam machines do not install concrete segments behind. Instead, the rock is held up using ground support methods such as ring beams, rock bolts, shotcrete, steel straps, ring steel and wire mesh.

In fractured rock, shielded TBMs can be used. They erect concrete segments behind the machine to support tunnel walls. Double Shield TBMs have two modes; in stable ground they grip the tunnel walls to advance. In unstable, fractured ground, the thrust is shifted to thrust cylinders that push against the tunnel segments behind the machine. This keeps the thrust forces from impacting fragile tunnel walls. Single Shield TBMs operate in the same way, but are used only in fractured ground, as they can only push against concrete segments.

In soft ground, the three main types of TBMs are: Earth Pressure Balance Machines (EPB), Slurry Shield (SS) and open-face. Both types of closed machines operate like Single Shield TBMs, using thrust cylinders to advance by pushing off against concrete segments. EPB machines are used in soft ground with less than 7 bar of pressure. The cutter head uses a combination of tungsten carbide cutting bits, carbide disc cutters, drag picks and/or hard rock disc cutters. The EPB machine's name come from the use of excavated material to create pressure at the tunnel face. Pressure is maintained by controlling the rate of extraction of spoil (using an Archimedes screw) and the advance rate. Additives such as bentonite, polymers and foam can be injected ahead of the face to increase ground stability. Additives can be injected in the cutterhead/extraction screw to ensure that the spoil remains sufficiently cohesive to form a plug in the screw to maintain pressure and restrict water flow.

In soft ground with high water pressure or where ground conditions are granular (sands and gravels) to the extent that a plug cannot be formed in the screw, Slurry Shield TBMs are employed. The cutterhead is filled with pressurised slurry that applies hydrostatic pressure to the excavation face. The slurry acts as a transport medium by mixing with the excavated material before it is pumped out of the cutterhead to a slurry separation plant, usually outside the tunnel. Slurry separation plants are multi-stage filtration systems, which separate spoil from the slurry to allow reuse. The limit to which slurry can be 'cleaned' depends on the relative particle size of the excavated material. Slurry TBMs are not suitable for silts and clays as the particle sizes of the spoil are less than that of the bentonite clay from which the slurry is made. In this case, the slurry is separated into water, which can be recycled and a clay cake, which may be polluted, that is pressed from the water.

Open face TBMs in soft ground rely on the face of the excavated ground to stand up without support for a short interval. This makes them suitable for use in rock types with a strength of up to 10MPa or so, and with low water inflows. Face sizes in excess of 10 metres can be excavated in this manner. The face is excavated using a backactor arm or cutter head to within 150mm of the edge of the shield. The shield is jacked forward and cutters on the front of the shield cut the remaining ground to the same circular shape. Ground support is provided by precast concrete, or occasionally

In soft ground, the three main types of TBMs are: Earth Pressure Balance Machines (EPB), Slurry Shield (SS) and open-face. Both types of closed machines operate like Single Shield TBMs, using thrust cylinders to advance by pushing off against concrete segments. EPB machines are used in soft ground with less than 7 bar of pressure. The cutter head uses a combination of tungsten carbide cutting bits, carbide disc cutters, drag picks and/or hard rock disc cutters. The EPB machine's name come from the use of excavated material to create pressure at the tunnel face. Pressure is maintained by controlling the rate of extraction of spoil (using an Archimedes screw) and the advance rate. Additives such as bentonite, polymers and foam can be injected ahead of the face to increase ground stability. Additives can be injected in the cutterhead/extraction screw to ensure that the spoil remains sufficiently cohesive to form a plug in the screw to maintain pressure and restrict water flow.

In soft ground with high water pressure or where ground conditions are granular (sands and gravels) to the extent that a plug cannot be formed in the screw, Slurry Shield TBMs are employed. The cutterhead is filled with pressurised slurry that applies hydrostatic pressure to the excavation face. The slurry acts as a transport medium by mixing with the excavated material before it is pumped out of the cutterhead to a slurry separation plant, usually outside the tunnel. Slurry separation plants are multi-stage filtration systems, which separate spoil from the slurry to allow reuse. The limit to which slurry can be 'cleaned' depends on the relative particle size of the excavated material. Slurry TBMs are not suitable for silts and clays as the particle sizes of the spoil are less than that of the bentonite clay from which the slurry is made. In this case, the slurry is separated into water, which can be recycled and a clay cake, which may be polluted, that is pressed from the water.

Open face TBMs in soft ground rely on the face of the excavated ground to stand up without support for a short interval. This makes them suitable for use in rock types with a strength of up to 10MPa or so, and with low water inflows. Face sizes in excess of 10 metres can be excavated in this manner. The face is excavated using a backactor arm or cutter head to within 150mm of the edge of the shield. The shield is jacked forward and cutters on the front of the shield cut the remaining ground to the same circular shape. Ground support is provided by precast concrete, or occasionally

2.M-30 EPB Tunnel Boring Machine – the largest built in the worldVideo on how a tunnel boring machine works

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tunnel Boring Machine British inventions 19th-century inventions

A tunnel boring machine (TBM), also known as a "mole", is a machine used to excavate tunnels with a circular cross section through a variety of soil and

A tunnel boring machine (TBM), also known as a "mole", is a machine used to excavate tunnels with a circular cross section through a variety of soil and rock strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as ei ...

. They may also be used for microtunneling. They can be designed to bore

Bore or Bores often refer to:

*Boredom

* Drill

Relating to holes

* Boring (manufacturing), a machining process that enlarges a hole

** Bore (engine), the diameter of a cylinder in a piston engine or a steam locomotive

** Bore (wind instruments), ...

through hard rock, wet or dry soil, or sand. Tunnel diameters can range from (micro-TBMs) to to date. Tunnels of less than a metre or so in diameter are typically done using trenchless construction methods or horizontal directional drilling

Directional boring, also referred to as horizontal directional drilling (HDD), is a minimal impact trenchless method of installing underground utilities such as pipe, conduit, or cables in a relatively shallow arc or radius along a prescribed und ...

rather than TBMs. TBMs can be designed to excavate non-circular tunnels, including u-shaped, horseshoe, square or rectangular tunnels.

Tunnel boring machines are used as an alternative to drilling and blasting (D&B) methods in rock and conventional "hand mining" in soil. TBMs have the advantages of limiting the disturbance to the surrounding ground and producing a smooth tunnel wall. This significantly reduces the cost of lining the tunnel, and makes them suitable to use in urban areas. The major disadvantage is the upfront cost. TBMs are expensive to construct, and can be difficult to transport. The longer the tunnel, the less the relative cost of tunnel boring machines versus drill and blast methods. This is because tunneling with appropriate TBMs is much more efficient and shortens completion times. Drilling and blasting however remain the preferred method when working through heavily fractured and sheared rock layers.

History

Henri Maus Michel Henri Joseph Maus (1808–1893) was a Belgian engineer, the inventor of the first tunnel boring machine.

Life

Maus was born in Namur (then in Sambre-et-Meuse, French First Empire) on 22 October 1808, the grandson of a German who had settled ...

's ''Mountain Slicer''. Commissioned by the King of Sardinia

The following is a list of rulers of Sardinia, in particular, of the monarchs of the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica from 1323 and then of the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1479 to 1861.

Early history

Owing to the absence of written sources, litt ...

in 1845 to dig the Fréjus Rail Tunnel between France and Italy through the Alps, Maus had it built in 1846 in an arms factory near Turin. It consisted of more than 100 percussion drills mounted in the front of a locomotive-sized machine, mechanically power-driven from the entrance of the tunnel. The Revolutions of 1848 affected the funding, and the tunnel was not completed until 10 years later, by using less innovative and less expensive methods such as pneumatic drills

Pneumatics (from Greek ‘wind, breath’) is a branch of engineering that makes use of gas or pressurized air.

Pneumatic systems used in industry are commonly powered by compressed air or compressed inert gases. A centrally located and e ...

.Hapgood, Fred, "The Underground Cutting Edge: The innovators who made digging tunnels high-tech",''Invention & Technology'' Vol.20, #2, Fall 2004In the United States, the first boring machine to have been built was used in 1853 during the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in northwest Massachusetts. Made of cast iron, it was known as ''Wilson's Patented Stone-Cutting Machine'', after inventor Charles Wilson. It drilled 10 feet into the rock before breaking down. (The tunnel was eventually completed more than 20 years later, and as with the Fréjus Rail Tunnel, by using less ambitious methods.) Wilson's machine anticipated modern TBMs in the sense that it employed cutting discs, like those of a disc harrow, which were attached to the rotating head of the machine. In contrast to traditional chiseling or drilling and blasting, this innovative method of removing rock relied on simple metal wheels to apply a transient high pressure that fractured the rock. In 1853, the American Ebenezer Talbot also patented a TBM that employed Wilson's cutting discs, although they were mounted on rotating arms, which in turn were mounted on a rotating plate. In the 1870s, John D. Brunton of England built a machine employing cutting discs that were mounted eccentrically on rotating plates, which in turn were mounted eccentrically on a rotating plate, so that the cutting discs would travel over almost all of the rock face that was to be removed. The first TBM that tunneled a substantial distance was invented in 1863 and improved in 1875 by British Army officer Major Frederick Edward Blackett Beaumont (1833–1895); Beaumont's machine was further improved in 1880 by British Army officer Major Thomas English (1843–1935). In 1875, the French National Assembly approved the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel and the British Parliament supported a trial run using English's TBM. Its cutting head consisted of a conical drill bit behind which were a pair of opposing arms on which were mounted cutting discs. From June 1882 to March 1883, the machine tunneled, through chalk, a total of 1,840 m (6,036 ft). A French engineer, Alexandre Lavalley, who was also a Suez Canal contractor, used a similar machine to drill 1,669 m (5,476 ft) from Sangatte on the French side. However, despite this success, the cross-Channel tunnel project was abandoned in 1883 after the British military raised fears that the tunnel might be used as an invasion route. Nevertheless, in 1883, this TBM was used to bore a railway ventilation tunnel — 7 feet (2.1 m) in diameter and 6,750 feet (2 km) long — between Birkenhead and Liverpool, England, through sandstone under the Mersey River. During the late 19th and early 20th century, inventors continued to design, build, and test TBMs in response to the need for tunnels for railroads, subways, sewers, water supplies, etc. TBMs employing rotating arrays of drills or hammers were patented. TBMs that resembled giant hole saws were proposed. Other TBMs consisted of a rotating drum with metal tines on its outer surface, or a rotating circular plate covered with teeth, or revolving belts covered with metal teeth. However, these TBMs proved expensive, cumbersome, and unable to excavate hard rock; interest in TBMs therefore declined. Nevertheless, TBM development continued in potash and coal mines, where the rock was softer. A TBM with a bore diameter of was manufactured by The Robbins Company for Canada's

Niagara Tunnel Project

The Niagara Tunnel Project was part of a series of major additions to the Sir Adam Beck hydroelectric generation complex in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada.

Water delivered by the major new tunnel complements other upgrades to the Sir Adam Beck ...

. The machine was used to bore a hydroelectric tunnel beneath Niagara Falls. The machine was named "Big Becky" in reference to the Sir Adam Beck hydroelectric dams to which it tunnelled to provide an additional hydroelectric tunnel.

An earth pressure balance TBM known as Bertha with a bore diameter of was produced by Hitachi Zosen Corporation in 2013. It was delivered to Seattle, Washington, for its Highway 99 tunnel project. The machine began operating in July 2013, but stalled in December 2013 and required substantial repairs that halted the machine until January 2016. Bertha completed boring the tunnel on April 4, 2017.

Two TBM's supplied by CREG excavated two tunnels for Kuala Lumpur's Rapid Transit with a boring diameter of 6,67m. The medium was water saturated sandy mudstone, schistose mudstone, highly weathered mudstone as well as alluvium. It achieved a maximum advance rate of more than 345m/month.

The world's largest ''hard rock'' TBM, known as Martina, was built by Herrenknecht AG. Its excavation diameter was , total length ; excavation area of , thrust value 39,485 t, total weight 4,500 tons, total installed capacity 18 MW. Its yearly energy consumption was about 62 million kWh). It is owned and operated by the Italian construction company Toto S.p.A. Costruzioni Generali (Toto Group) for the Sparvo gallery of the Italian Motorway Pass A1 ("Variante di Valico A1"), near Florence. The same company built the world's largest-diameter slurry TBM, excavation diameter of , owned and operated by the French construction company Dragages Hong Kong (Bouygues' subsidiary) for the Tuen Mun Chek Lap Kok link in Hong Kong.

Types

Modern TBMs typically consist of the rotating cutting wheel, called a cutter head, followed by a main bearing, a thrust system and trailing support mechanisms. The type of machine used depends on the particular geology of the project, the amount of ground water present and other factors.Hard rock TBMs

In hard rock, either shielded or open-type TBMs can be used. Hard rock TBMs cut rock with discs mounted in the cutter head. The disc cutters create compressive stress fractures in the rock, cracking chips from the tunnel face. The excavated rock (muck) is transferred through openings in the cutter head to a belt conveyor that carries it through the machine to a system of conveyors or muck cars.

Open-type TBMs have no shield, leaving the area behind the cutter head open for rock support. To advance, the machine uses a gripper system that pushes against the tunnel walls. Machines such as a Wirth machine can be steered only while ungripped. Other machines can be continuously steered. When gripped, the machine pushes forward. At the end of a cycle, the rear legs are lowered, while the grippers and propel cylinders are retracted and the machine advances. The grippers then reengage and the rear legs lift for the next boring cycle.

Open-type, or Main Beam machines do not install concrete segments behind. Instead, the rock is held up using ground support methods such as ring beams, rock bolts, shotcrete, steel straps, ring steel and wire mesh.

In fractured rock, shielded TBMs can be used. They erect concrete segments behind the machine to support tunnel walls. Double Shield TBMs have two modes; in stable ground they grip the tunnel walls to advance. In unstable, fractured ground, the thrust is shifted to thrust cylinders that push against the tunnel segments behind the machine. This keeps the thrust forces from impacting fragile tunnel walls. Single Shield TBMs operate in the same way, but are used only in fractured ground, as they can only push against concrete segments.

In hard rock, either shielded or open-type TBMs can be used. Hard rock TBMs cut rock with discs mounted in the cutter head. The disc cutters create compressive stress fractures in the rock, cracking chips from the tunnel face. The excavated rock (muck) is transferred through openings in the cutter head to a belt conveyor that carries it through the machine to a system of conveyors or muck cars.

Open-type TBMs have no shield, leaving the area behind the cutter head open for rock support. To advance, the machine uses a gripper system that pushes against the tunnel walls. Machines such as a Wirth machine can be steered only while ungripped. Other machines can be continuously steered. When gripped, the machine pushes forward. At the end of a cycle, the rear legs are lowered, while the grippers and propel cylinders are retracted and the machine advances. The grippers then reengage and the rear legs lift for the next boring cycle.

Open-type, or Main Beam machines do not install concrete segments behind. Instead, the rock is held up using ground support methods such as ring beams, rock bolts, shotcrete, steel straps, ring steel and wire mesh.

In fractured rock, shielded TBMs can be used. They erect concrete segments behind the machine to support tunnel walls. Double Shield TBMs have two modes; in stable ground they grip the tunnel walls to advance. In unstable, fractured ground, the thrust is shifted to thrust cylinders that push against the tunnel segments behind the machine. This keeps the thrust forces from impacting fragile tunnel walls. Single Shield TBMs operate in the same way, but are used only in fractured ground, as they can only push against concrete segments.

Soft ground TBMs

In soft ground, the three main types of TBMs are: Earth Pressure Balance Machines (EPB), Slurry Shield (SS) and open-face. Both types of closed machines operate like Single Shield TBMs, using thrust cylinders to advance by pushing off against concrete segments. EPB machines are used in soft ground with less than 7 bar of pressure. The cutter head uses a combination of tungsten carbide cutting bits, carbide disc cutters, drag picks and/or hard rock disc cutters. The EPB machine's name come from the use of excavated material to create pressure at the tunnel face. Pressure is maintained by controlling the rate of extraction of spoil (using an Archimedes screw) and the advance rate. Additives such as bentonite, polymers and foam can be injected ahead of the face to increase ground stability. Additives can be injected in the cutterhead/extraction screw to ensure that the spoil remains sufficiently cohesive to form a plug in the screw to maintain pressure and restrict water flow.

In soft ground with high water pressure or where ground conditions are granular (sands and gravels) to the extent that a plug cannot be formed in the screw, Slurry Shield TBMs are employed. The cutterhead is filled with pressurised slurry that applies hydrostatic pressure to the excavation face. The slurry acts as a transport medium by mixing with the excavated material before it is pumped out of the cutterhead to a slurry separation plant, usually outside the tunnel. Slurry separation plants are multi-stage filtration systems, which separate spoil from the slurry to allow reuse. The limit to which slurry can be 'cleaned' depends on the relative particle size of the excavated material. Slurry TBMs are not suitable for silts and clays as the particle sizes of the spoil are less than that of the bentonite clay from which the slurry is made. In this case, the slurry is separated into water, which can be recycled and a clay cake, which may be polluted, that is pressed from the water.

Open face TBMs in soft ground rely on the face of the excavated ground to stand up without support for a short interval. This makes them suitable for use in rock types with a strength of up to 10MPa or so, and with low water inflows. Face sizes in excess of 10 metres can be excavated in this manner. The face is excavated using a backactor arm or cutter head to within 150mm of the edge of the shield. The shield is jacked forward and cutters on the front of the shield cut the remaining ground to the same circular shape. Ground support is provided by precast concrete, or occasionally

In soft ground, the three main types of TBMs are: Earth Pressure Balance Machines (EPB), Slurry Shield (SS) and open-face. Both types of closed machines operate like Single Shield TBMs, using thrust cylinders to advance by pushing off against concrete segments. EPB machines are used in soft ground with less than 7 bar of pressure. The cutter head uses a combination of tungsten carbide cutting bits, carbide disc cutters, drag picks and/or hard rock disc cutters. The EPB machine's name come from the use of excavated material to create pressure at the tunnel face. Pressure is maintained by controlling the rate of extraction of spoil (using an Archimedes screw) and the advance rate. Additives such as bentonite, polymers and foam can be injected ahead of the face to increase ground stability. Additives can be injected in the cutterhead/extraction screw to ensure that the spoil remains sufficiently cohesive to form a plug in the screw to maintain pressure and restrict water flow.

In soft ground with high water pressure or where ground conditions are granular (sands and gravels) to the extent that a plug cannot be formed in the screw, Slurry Shield TBMs are employed. The cutterhead is filled with pressurised slurry that applies hydrostatic pressure to the excavation face. The slurry acts as a transport medium by mixing with the excavated material before it is pumped out of the cutterhead to a slurry separation plant, usually outside the tunnel. Slurry separation plants are multi-stage filtration systems, which separate spoil from the slurry to allow reuse. The limit to which slurry can be 'cleaned' depends on the relative particle size of the excavated material. Slurry TBMs are not suitable for silts and clays as the particle sizes of the spoil are less than that of the bentonite clay from which the slurry is made. In this case, the slurry is separated into water, which can be recycled and a clay cake, which may be polluted, that is pressed from the water.

Open face TBMs in soft ground rely on the face of the excavated ground to stand up without support for a short interval. This makes them suitable for use in rock types with a strength of up to 10MPa or so, and with low water inflows. Face sizes in excess of 10 metres can be excavated in this manner. The face is excavated using a backactor arm or cutter head to within 150mm of the edge of the shield. The shield is jacked forward and cutters on the front of the shield cut the remaining ground to the same circular shape. Ground support is provided by precast concrete, or occasionally spheroidal graphite iron

Ductile iron, also known as ductile cast iron, nodular cast iron, spheroidal graphite iron, spheroidal graphite cast iron and SG iron, is a type of graphite-rich cast iron discovered in 1943 by Keith Millis. While most varieties of cast iron ar ...

(SGI) segments that are bolted or supported until a full support ring has been erected. A final segment, called the key, is wedge-shaped, and expands the ring until it is tight against the circular cut of the ground left behind.

While the use of TBMs relieves the need for large numbers of workers to labor at high pressures, a caisson system is sometimes formed at the cutting head for slurry shield TBMs. Workers entering this space for inspection, maintenance and repair need to be medically cleared as "fit to dive" (to survive the elevated pressure) and trained in the operation of the locks.

Herrenknecht AG designed a soft ground TBM for the Orlovski Tunnel, a project in Saint Petersburg, but it was never built.

Micro-tunnel shield method

Micro tunnel shield method is a digging technique used to construct small tunnels, and diminish in size of general tunnelling shield. Micro tunnel boring machines are quite similar to general tunnelling shields but on a smaller scale. They generally vary from , too small for operators to walk in.Backup systems

Behind all types of tunnel boring machines, in the finished part of the tunnel, are trailing support decks known as the backup system, whose mechanisms can include conveyors or other systems for muck removal; slurry pipelines (if applicable); control rooms; electrical, dust-removal and ventilation systems; and mechanisms for transport of pre-cast segments.Urban tunnelling and near-surface tunnelling

Urban tunnelling has the special requirement that the surface remain undisturbed, and that groundsubsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope move ...

be avoided. The normal method of doing this in soft ground is to maintain soil pressures during and after construction.

TBMs with positive face control, such as EPB and SS, are used in such situations. Both types (EPB and SS) are capable of reducing the risk of surface subsidence and voids if ground conditions are well documented. When tunnelling in urban environments, other tunnels, existing utility lines and deep foundations must be considered, and the project must accommodate measures to mitigate any detrimental effects to other infrastructure.

See also

*Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (french: Tunnel sous la Manche), also known as the Chunnel, is a railway tunnel that connects Folkestone (Kent, England, UK) with Coquelles ( Hauts-de-France, France) beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. ...

* New Austrian Tunnelling method

* Roadheader

* Subterrene

* Trenchless technology

Notes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

2.M-30 EPB Tunnel Boring Machine – the largest built in the world

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tunnel Boring Machine British inventions 19th-century inventions