Bordar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Serfdom was the status of many

, T Wangchuk ''Change in the land use system in Bhutan: Ecology, History, Culture, and Power'' Nature Conservation Section. DoF, MoA The

Social institutions similar to serfdom were known in

Social institutions similar to serfdom were known in

The word ''serf'' originated from the

The word ''serf'' originated from the

Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family. In England, at the time of the Domesday Survey, this would have comprised between about .Daniel D. McGarry, ''Medieval History and Civilization'' (1976) p 242 Under an Elizabethan

Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family. In England, at the time of the Domesday Survey, this would have comprised between about .Daniel D. McGarry, ''Medieval History and Civilization'' (1976) p 242 Under an Elizabethan

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his

*

* Emancipation of the Serfs

* Georgia: 1864–1871 *

excerpt and text search

* Freedman, Paul, and Monique Bourin, eds. ''Forms of Servitude in Northern and Central Europe. Decline, Resistance and Expansion'' Brepols, 2005. * Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat, eds. ''The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England''. Glasgow: Cruithne P, 1994. * Gorshkov, Boris B. "Serfdom: Eastern Europe" in Peter N. Stearns, ed, ''Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000'' (2001) volume 2 pp. 379–88 * Hoch, Steven L. ''Serfdom and social control in Russia: Petrovskoe, a village in Tambov'' (1989) * Kahan, Arcadius. "Notes on Serfdom in Western and Eastern Europe," ''Journal of Economic History'' March 1973 33:86–9

in JSTOR

* Kolchin, Peter. ''Unfree labor: American slavery and Russian serfdom'' (2009) * Moon, David. ''The abolition of serfdom in Russia 1762–1907'' (Longman, 2001) * Scott, Tom, ed. ''The Peasantries of Europe'' (1998) * Vadey, Liana. "Serfdom: Western Europe" in Peter N. Stearns, ed, ''Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000'' (2001) volume 2 pp. 369–78 * White, Stephen D. ''Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe'' (2nd ed. Ashgate Variorum, 2000) * Wirtschafter, Elise Kimerling. ''Russia's age of serfdom 1649–1861'' (2008) * Wright, William E. ''Serf, Seigneur, and Sovereign: Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-century Bohemia'' (U of Minnesota Press, 1966). * Wunder, Heide. "Serfdom in later medieval and early modern Germany" in T. H. Aston et al., ''Social Relations and Ideas: Essays in Honour of R. H. Hilton'' (Cambridge UP, 1983), 249–72

Serfdom

''

The Hull Project

''

Peasantry (social class)

''Encyclopædia Britannica''.

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20030514164951/http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/movable_type/2003_archives/001447.html The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis discussion and full online text of

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

s under feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

, specifically relating to manorialism

Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes forti ...

, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

with similarities to and differences from slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, which developed during the Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

and Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.

Unlike slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s, serfs could not be bought, sold, or traded individually though they could, depending on the area, be sold together with land. The kholop

A kholop ( rus, холо́п, p=xɐˈlop) was a type of feudal serf in Kievan Rus', then in Russia between the 10th and early 18th centuries. Their legal status was close to that of slaves.

Etymology

The word ''kholop'' was first mentioned in ...

s in Russia, by contrast, could be traded like regular slaves, could be abused with no rights over their own bodies, could not leave the land they were bound to, and could marry only with their lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or ar ...

's permission. Serfs who occupied a plot of land were required to work for the lord of the manor

Lord of the Manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England, referred to the landholder of a rural estate. The lord enjoyed manorial rights (the rights to establish and occupy a residence, known as the manor house and demesne) as well as seig ...

who owned that land. In return, they were entitled to protection, justice, and the right to cultivate certain fields within the manor to maintain their own subsistence. Serfs were often required not only to work on the lord's fields, but also in his mines and forests and to labour to maintain roads. The manor formed the basic unit of feudal society, and the lord of the manor and the villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s, and to a certain extent the serfs, were bound legally: by taxation in the case of the former, and economically and socially in the latter.

The decline of serfdom in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

has sometimes been attributed to the widespread plague epidemic of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

, which reached Europe in 1347 and caused massive fatalities, disrupting society. Conversely, serfdom grew stronger in Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

, where it had previously been less common (this phenomenon was known as "later serfdom").

In Eastern Europe, the institution persisted until the mid-19th century. In the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

, serfdom was abolished by the 1781 Serfdom Patent; corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

s continued to exist until 1848. Serfdom was abolished in Russia in 1861. Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

declared serfdom unacceptable in its General State Laws for the Prussian States

The General State Laws for the Prussian States (german: Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preußischen Staaten, ALR) were an important code of Prussia, promulgated in 1792 and codified by Carl Gottlieb Svarez and Ernst Ferdinand Klein, under the ...

in 1792 and finally abolished it in October 1807, in the wake of the Prussian Reform Movement

The Prussian Reform Movement was a series of constitutional, administrative, social and economic reforms early in nineteenth-century Prussia. They are sometimes known as the Stein-Hardenberg Reforms, for Karl Freiherr vom Stein and Karl August ...

. In Finland, Norway, and Sweden, feudalism was never fully established, and serfdom did not exist; in Denmark, serfdom-like institutions did exist in both ''s'' (the ''stavnsbånd

The Stavnsbånd was a serfdom-like institution introduced in Denmark in 1733 in accordance with the wishes of estate owners and the military. It bonded men between the ages of 14 and 36 to live on the estate where they were born. It was possible, ...

'', from 1733 to 1788) and its vassal Iceland (the more restrictive ''vistarband

The Icelandic vistarband () was a requirement that all landless people be employed on a farm. A person who did not own or lease property had to find a position as a laborer (''vinnuhjú'' ) in the home of a farmer. The custom was for landless peopl ...

'', from 1490 until 1894).

According to medievalist

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vo ...

historian Joseph R. Strayer

Joseph Reese Strayer (1904–1987) was an American medievalist historian. He was a student of and mentored by Charles Homer Haskins, America's first prominent medievalist historian.

Life

Strayer taught at Princeton University for many decades, s ...

, the concept of feudalism can also be applied to the societies of ancient Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

( Sixth to Twelfth dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some ...

), Islamic-ruled Northern and Central India, China (Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by th ...

and end of Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

) and Japan during the Shogunate. Wu Ta-k'un argued that the Shang-Zhou fengjian

''Fēngjiàn'' ( zh, c=封建, l=enfeoffment and establishment) was a political ideology and governance system in ancient China, whose social structure formed a decentralized system of confederation-like government based on the ruling class consis ...

were kinship estates, quite distinct from feudalism. James Lee and Cameron Campbell describe the Chinese Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

(1644–1912) as also maintaining a form of serfdom.

Melvyn Goldstein

Melvyn C. Goldstein (born February 8, 1938) is an American social anthropologist and Tibet scholar. He is a professor of anthropology at Case Western Reserve University and a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

His research focuses on ...

described Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

as having had serfdom until 1959, but whether or not the Tibetan form of peasant tenancy that qualified as serfdom was widespread is contested by other scholars.Barnett, Robert (2008) "What were the conditions regarding human rights in Tibet before democratic reform?" in: ''Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China’s 100 Questions,'' pp. 81–83. Eds. Anne-Marie Blondeau and Katia Buffetrille. University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by faculty ...

. (cloth); (paper) Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainous ...

is described by Tashi Wangchuk, a Bhutanese civil servant, as having officially abolished serfdom by 1959, but he believes that less than or about 10% of poor peasants were in copyhold

Copyhold was a form of customary land ownership common from the Late Middle Ages into modern times in England. The name for this type of land tenure is derived from the act of giving a copy of the relevant title deed that is recorded in the ma ...

situations.BhutanStudies.org.bt, T Wangchuk ''Change in the land use system in Bhutan: Ecology, History, Culture, and Power'' Nature Conservation Section. DoF, MoA The

United Nations 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery

The Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the full title of which is the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery, is a 1956 United Nations treaty wh ...

also prohibits serfdom as a practice similar to slavery.

History

ancient times

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

. The status of the helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their e ...

in the ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

of Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

resembled that of the medieval serfs. By the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

faced a labour shortage. Large Roman landowners increasingly relied on Roman freemen, acting as tenant farmers, instead of slaves to provide labour.

These tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a person (farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, ...

s, eventually known as ''coloni'', saw their condition steadily erode. Because the tax system implemented by Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

assessed taxes based on both land and the inhabitants of that land, it became administratively inconvenient for peasants to leave the land where they were counted in the census.

Medieval serfdom really began with the breakup of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lom ...

around the 10th century. During this period, powerful feudal lords

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

encouraged the establishment of serfdom as a source of agricultural labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

. Serfdom, indeed, was an institution that reflected a fairly common practice whereby great landlords were assured that others worked to feed them and were held down, legally and economically, while doing so.

This arrangement provided most of the agricultural labour throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

persisted right through the Middle Ages, but it was rare.

In the later Middle Ages serfdom began to disappear west of the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

even as it spread through eastern Europe. Serfdom reached Eastern Europe centuries later than Western Europeit became dominant around the 15th century. In many of these countries serfdom was abolished during the Napoleonic invasions of the early 19th century, though in some it persisted until mid- or late- 19th century.

Etymology

The word ''serf'' originated from the

The word ''serf'' originated from the Middle French

Middle French (french: moyen français) is a historical division of the French language that covers the period from the 14th to the 16th century. It is a period of transition during which:

* the French language became clearly distinguished from t ...

and was derived from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

("slave"). In Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

and most of the Middle Ages, what are now called serfs were usually designated in Latin as . As slavery gradually disappeared and the legal status of became nearly identical to that of the , the term changed meaning into the modern concept of "serf". The word "serf" is first recorded in English in the late 15th century, and came to its current definition in the 17th century. ''Serfdom'' was coined in 1850.

Dependency and the lower orders

Serfs had a specific place in feudal society, as didbarons

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

and knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

s: in return for protection, a serf would reside upon and work a parcel of land within the manor of his lord. Thus, the manorial system exhibited a degree of reciprocity.

One rationale held that serfs and freemen "worked for all" while a knight or baron "fought for all" and a churchman "prayed for all"; thus everyone had a place. The serf was the worst fed and rewarded however, although unlike slaves had certain rights in land and property.

A lord of the manor could not sell his serfs as a Roman might sell his slaves. On the other hand, if he chose to dispose of a parcel of land, the serfs associated with that land stayed with it to serve their new lord; simply speaking, they were implicitly sold in mass and as a part of a lot. This unified system preserved for the lord long-acquired knowledge of practices suited to the land. Further, a serf could not abandon his lands without permission, nor did he possess a saleable title in them.

Initiation

Afreeman

Freeman, free men, or variant, may refer to:

* a member of the Third Estate in medieval society (commoners), see estates of the realm

* Freeman, an apprentice who has been granted freedom of the company, was a rank within Livery companies

* Free ...

became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes the greater physical and legal force of a local magnate intimidated freeholders or allodial

Allodial title constitutes ownership of real property (land, buildings, and fixtures) that is independent of any superior landlord. Allodial title is related to the concept of land held "in allodium", or land ownership by occupancy and defens ...

owners into dependency. Often a few years of crop failure, a war, or brigandage might leave a person unable to make his own way. In such a case, he could strike a bargain with a lord of a manor. In exchange for gaining protection, his service was required: in labour, produce, or cash, or a combination of all. These bargains became formalised in a ceremony known as "bondage", in which a serf placed his head in the lord's hands, akin to the ceremony of homage where a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

placed his hands between those of his overlord. These oaths bound the lord and his new serf in a feudal contract and defined the terms of their agreement. Often these bargains were severe.

A 7th-century Anglo Saxon "Oath of Fealty" states:

To become a serf was a commitment that encompassed all aspects of the serf's life. The children born to serfs inherited their status, and were considered born into serfdom. By taking on the duties of serfdom, people bound themselves and their progeny.

Class system

The social class of thepeasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

ry can be differentiated into smaller categories. These distinctions were often less clear than suggested by their different names. Most often, there were two types of peasants:

# freemen, workers whose tenure within the manor was freehold

Freehold may refer to:

In real estate

*Freehold (law), the tenure of property in fee simple

* Customary freehold, a form of feudal tenure of land in England

* Parson's freehold, where a Church of England rector or vicar of holds title to benefice ...

# villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

Lower classes of peasants, known as cottar

Cotter, cottier, cottar, or is the German or Scots term for a peasant farmer (formerly in the Scottish Highlands for example). Cotters occupied cottages and cultivated small land lots. The word ''cotter'' is often employed to translate th ...

s or bordars, generally comprising the younger sons of villeins; vagabonds; and slaves, made up the lower class of workers.

Coloni

The system of the late Roman Empire can be considered the predecessor of Western Europeanfeudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

serfdom.

Freemen

Freemen, orfree tenant

Free tenants, also known as free peasants, were tenant farmer peasants in medieval England who occupied a unique place in the medieval hierarchy. They were characterized by the low rents which they paid to their manorial lord. They were subj ...

s held their land by one of a variety of contracts of feudal land-tenure and were essentially rent-paying tenant farmers who owed little or no service to the lord, and had a good degree of security of tenure and independence. In parts of 11th-century England freemen made up only 10% of the peasant population, and in most of the rest of Europe their numbers were also small.

Ministeriales

Ministeriales

The ''ministeriales'' (singular: ''ministerialis'') were a class of people raised up from serfdom and placed in positions of power and responsibility in the High Middle Ages in the Holy Roman Empire.

The word and its German translations, ''Minis ...

were hereditary unfree knights tied to their lord, that formed the lowest rung of nobility in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

.

Villeins

A villein (or ''villain'') represented the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and higher status than the lowest serf, but existed under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from freemen. Villeins generally rented small homes, with a patch of land. As part of the contract with thelandlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, the ...

, the lord of the manor, they were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord's fields. The requirement often was not greatly onerous, contrary to popular belief, and was often only seasonal, for example the duty to help at harvest-time. The rest of their time was spent farming their own land for their own profit. Villeins were tied to their lord's land and couldn't leave it without his permission. Their lord also often decided whom they could marry.

Like other types of serfs, villeins had to provide other services, possibly in addition to paying rent of money or produce. Villeins were somehow retained on their land and by unmentioned manners could not move away without their lord's consent and the acceptance of the lord to whose manor they proposed to migrate to. Villeins were generally able to hold their own property, unlike slaves. Villeinage, as opposed to other forms of serfdom, was most common in Continental European feudalism, where land ownership had developed from roots in Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

.

A variety of kinds of villeinage existed in Europe in the Middle Ages. Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of labour to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship. Villeinage was not a purely uni-directional exploitative relationship. In the Middle Ages, land within a lord's manor provided sustenance and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land, and crops secure from theft by marauding robbers. Landlords, even where legally entitled to do so, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labour. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an unlanded labourer.

In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping from a manor to a city or borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

and living there for more than a year; but this action involved the loss of land rights and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult.

In medieval England, two types of villeins existed–''villeins regardant'' that were tied to land and ''villeins in gross'' that could be traded separately from land.

Bordars and cottagers

In England, theDomesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

, of 1086, uses (bordar) and (cottar

Cotter, cottier, cottar, or is the German or Scots term for a peasant farmer (formerly in the Scottish Highlands for example). Cotters occupied cottages and cultivated small land lots. The word ''cotter'' is often employed to translate th ...

) as interchangeable terms, ''cottar'' deriving from the native Anglo-Saxon tongue whereas ''bordar'' derived from the French.

Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family. In England, at the time of the Domesday Survey, this would have comprised between about .Daniel D. McGarry, ''Medieval History and Civilization'' (1976) p 242 Under an Elizabethan

Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family. In England, at the time of the Domesday Survey, this would have comprised between about .Daniel D. McGarry, ''Medieval History and Civilization'' (1976) p 242 Under an Elizabethan statute

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by le ...

, the Erection of Cottages Act 1588

The Erection of Cottages Act 1588 was an Act of the Parliament of England that prohibited the construction—in most parts of England—of any dwelling that did not have at least assigned to it out of the freehold or other heritable land belongin ...

, the cottage had to be built with at least of land. The later Enclosures Acts (1604 onwards) removed the cottars' right to any land: "before the Enclosures Act the cottager was a farm labourer with land and after the Enclosures Act the cottager was a farm labourer without land".

The bordars and cottars did not own their draught oxen or horses. The Domesday Book showed that England comprised 12% freeholders, 35% serfs or villeins, 30% cotters and bordars, and 9% slaves.

Smerd

Smerdy were a type of serfs above kholops inMedieval Poland

This article covers the history of Poland in the Middle Ages. This time covers roughly a millennium, from the 5th century to the 16th century. It is commonly dated from the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, and contrasted with a later Early Modern ...

and Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

.

Kholops

Kholop

A kholop ( rus, холо́п, p=xɐˈlop) was a type of feudal serf in Kievan Rus', then in Russia between the 10th and early 18th centuries. Their legal status was close to that of slaves.

Etymology

The word ''kholop'' was first mentioned in ...

s were the lowest class of serfs in the medieval and early modern Russia. They had status similar to slaves, and could be freely traded.

Slaves

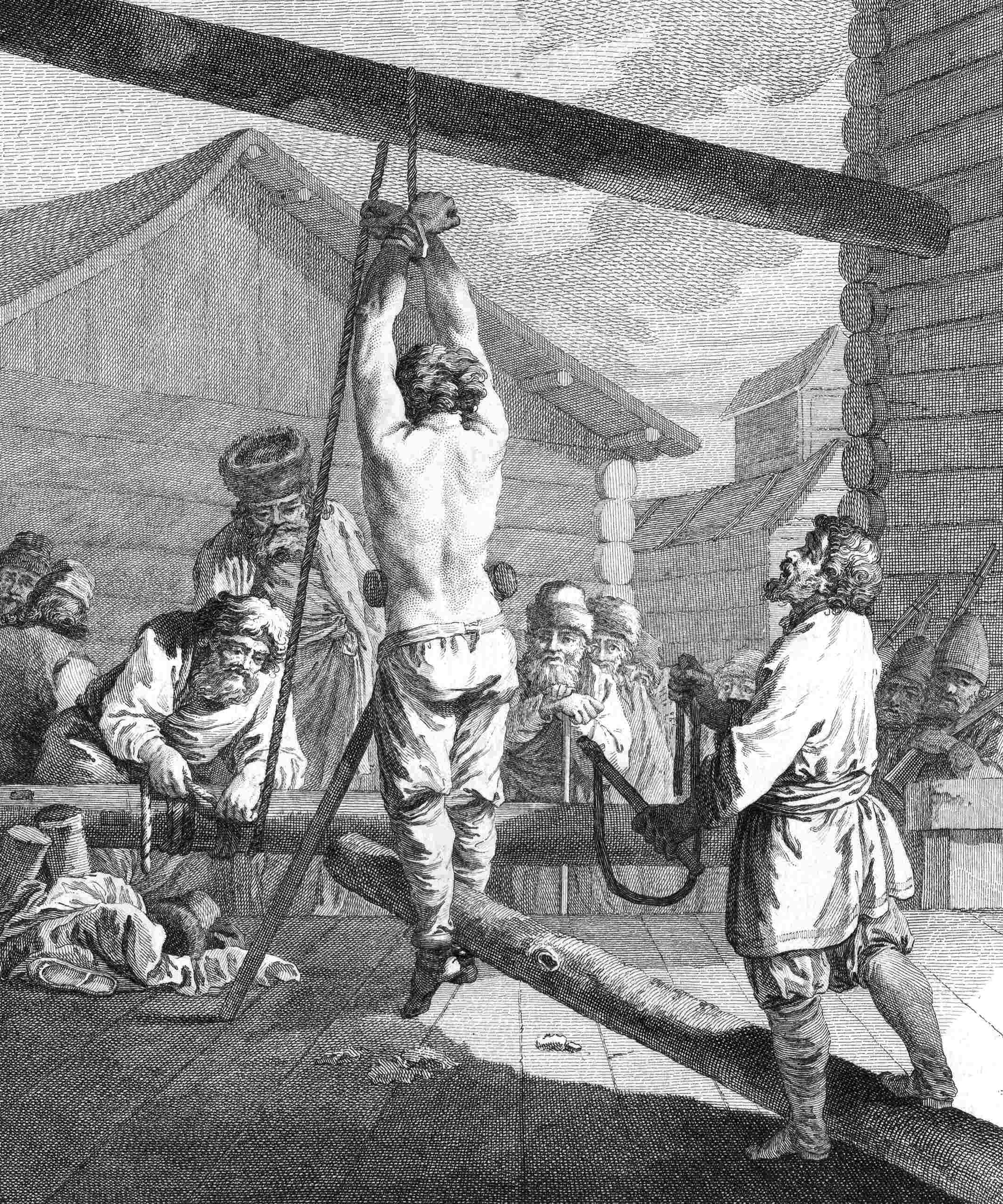

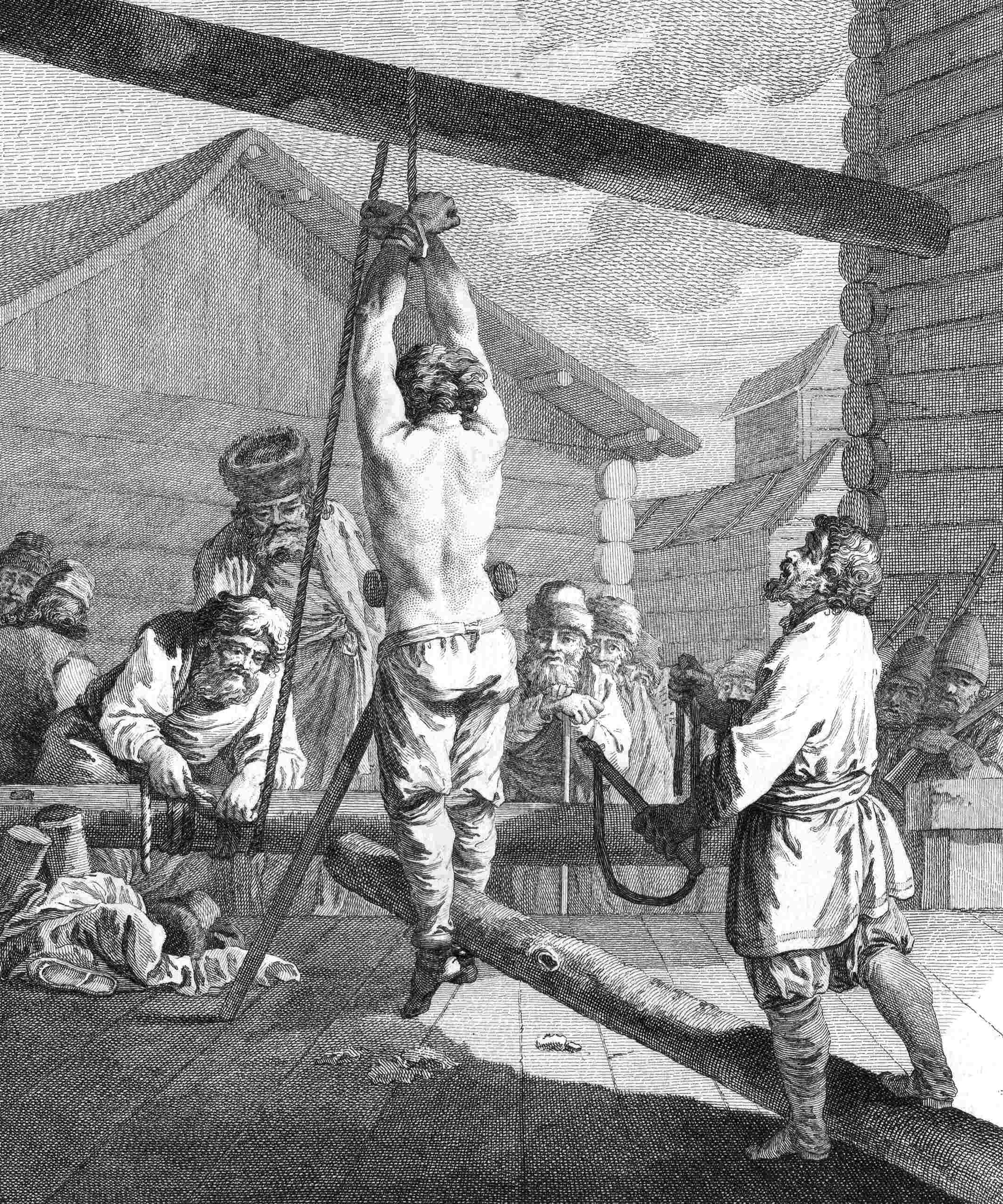

The last type of serf was the slave. Slaves had the fewest rights and benefits from the manor. They owned no tenancy in land, worked for the lord exclusively and survived on donations from the landlord. It was always in the interest of the lord to prove that a servile arrangement existed, as this provided him with greater rights to fees and taxes. The status of a man was a primary issue in determining a person's rights and obligations in many of the manorial court-cases of the period. Also, runaway slaves could be beaten if caught. Serfdom was significantly more common than slavery throughout the feudal period. The villein was the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and status than those held as slaves, but were under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from the freeman. Within his constraints, a serf had some freedom. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned “only his belly”—even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord—a serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbors, although this was rather an exception to the general rule. A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom.Duties

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his fee

A fee is the price one pays as remuneration for rights or services. Fees usually allow for overhead, wages, costs, and markup. Traditionally, professionals in the United Kingdom (and previously the Republic of Ireland) receive a fee in cont ...

s and tax

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or n ...

es in the form of seasonally appropriate labour. Usually, a portion of the week was devoted to ploughing his lord's fields held in demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

, harvesting crops, digging ditches, repairing fences, and often working in the manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals w ...

. The remainder of the serf's time he spent tending his own fields, crops and animals in order to provide for his family. Most manorial work was segregated by gender

Gender is the range of characteristics pertaining to femininity and masculinity and differentiating between them. Depending on the context, this may include sex-based social structures (i.e. gender roles) and gender identity. Most cultures u ...

during the regular times of the year. During the harvest, the whole family was expected to work the fields.

A major difficulty of a serf's life was that his work for his lord coincided with, and took precedence over, the work he had to perform on his own lands: when the lord's crops were ready to be harvested, so were his own. On the other hand, the serf of a benign lord could look forward to being well fed during his service; it was a lord without foresight who did not provide a substantial meal for his serfs during the harvest and planting times. In exchange for this work on the lord's demesne, the serfs had certain privileges and rights, including for example the right to gather deadwood – an essential source of fuel – from their lord's forests.

In addition to service, a serf was required to pay certain taxes

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, o ...

and fees. Taxes were based on the assessed value of his lands and holdings. Fees were usually paid in the form of agricultural produce rather than cash. The best ration of wheat from the serf's harvest often went to the landlord. Generally hunting and trapping of wild game by the serfs on the lord's property was prohibited. On Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel P ...

the peasant family perhaps might owe an extra dozen eggs, and at Christmas, a goose was perhaps required, too. When a family member died, extra taxes were paid to the lord as a form of feudal relief Feudal relief was a one-off "fine" or form of taxation payable to an overlord by the heir of a feudal tenant to license him to take possession of his fief, i.e. an estate-in-land, by inheritance. It is comparable to a death duty or inheritance ta ...

to enable the heir to keep the right to till what land he had. Any young woman who wished to marry a serf outside of her manor was forced to pay a fee for the right to leave her lord, and in compensation for her lost labour.

Often there were arbitrary tests to judge the worthiness of their tax payments. A chicken, for example, might be required to be able to jump over a fence of a given height to be considered old enough or well enough to be valued for tax purposes. The restraints of serfdom on personal and economic choice were enforced through various forms of manorial customary law and the manorial administration and court baron.

It was also a matter of discussion whether serfs could be required by law in times of war or conflict to fight for their lord's land and property. In the case of their lord's defeat, their own fate might be uncertain, so the serf certainly had an interest in supporting his lord.

Rights

Within his constraints, a serf had some freedoms. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned "only his belly"even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lorda serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbours, although this happened rarely. A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom. A serf could grow what crop he saw fit on his lands, although a serf's taxes often had to be paid in wheat. The surplus he would sell atmarket

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

.

The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without legal cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of robbers or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

. Many such rights were enforceable by the serf in the manorial court.

Variations

Forms of serfdom varied greatly through time and regions. In some places, serfdom was merged with or exchanged for various forms of taxation. The amount of labour required varied. In Poland, for example, it was commonly a few days per year per household in the 13th century, one day per week per household in the 14th century, four days per week per household in the 17th century, and six days per week per household in the 18th century. Early serfdom in Poland was mostly limited to the royal territories (''królewszczyzny

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an Fee tail, entailed Estate (land), estate and passes with the monarchy, be ...

'').

"Per household" means that every dwelling had to give a worker for the required number of days. For example, in the 18th century, six people: a peasant, his wife, three children and a hired worker might be required to work for their lord one day a week, which would be counted as six days of labour.

Serfs served on occasion as soldiers in the event of conflict and could earn freedom or even ennoblement

Ennoblement is the conferring of nobility—the induction of an individual into the noble class. Currently only a few kingdoms still grant nobility to people; among them Spain, the United Kingdom, Belgium and the Vatican. Depending on time and regi ...

for valour in combat. Serfs could purchase their freedom, be manumitted

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that ...

by generous owners, or flee to towns or to newly settled land where few questions were asked. Laws varied from country to country: in England a serf who made his way to a chartered town (i.e. a borough) and evaded recapture for a year and a day obtained his freedom and became a burgher

Burgher may refer to:

* Burgher (social class), a medieval, early modern European title of a citizen of a town, and a social class from which city officials could be drawn

** Burgess (title), a resident of a burgh in northern Britain

** Grand Bu ...

of the town.

Serfdom by country and location

Americas

Aztec Empire

In the Aztec Empire, the Tlacotin class held similarities to serfdom. Even at its height, slaves only ever made up 2% of the population.Byzantine Empire

Theparoikoi ''Paroikoi'' (plural of Greek πάροικος, ''paroikos'', the etymological origin of parish and parochial) is the term that replaced " metic" in the Hellenistic and Roman period to designate foreign residents.

In the Byzantine Empire, ''paroiko ...

were the Byzantine equivalent of serfs.

France

Serfdom in France started to diminish after theBlack Death in France

The Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in hu ...

, when the lack of work force made manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

more common from that point onward, and by the 18th-century, serfdom had become relatively rare in most of France.

In 1779, the reforms of Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker (; 30 September 1732 – 9 April 1804) was a Genevan banker and statesman who served as finance minister for Louis XVI. He was a reformer, but his innovations sometimes caused great discontent. Necker was a constitutional monarchi ...

abolished serfdom in all Crown lands in France. On the outbreak of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

of 1789, between 140.000 and 1,500,000 serfs remained in France, most of them on clerical lands in Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; frp, Franche-Comtât; also german: Freigrafschaft; es, Franco Condado; all ) is a cultural and historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of Doubs, ...

, Berry, Burgundy and Marche.

However, although formal serfdom no longer existed in most of France, the feudal seigneurial laws still granted noble landlords many of the rights previously exercised over serfs, and the peasants of Auvergne, Nivernais and Champagne, though formally not serfs, could still not move freely.

Serfdom was formally abolished in France on 4 August 1789, and the remaining feudal rights that gave landlords control rights over peasants were abolished in 1789-93.

Ireland

Gaelic Ireland

InGaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans co ...

, a political and social system existing in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

from the prehistoric period (500 BC or earlier) up until the Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

(12th century AD), the ("hut-dweller"), (perhaps linked to , "soil") and ("old dwelling-house") were low-ranked semi-free servile tenants similar to serfs. According to Laurence Ginnell, the and "were not free to leave the territory except with permission, and in practice they usually served the ''flaith

{{Use dmy dates, date=April 2022

A flaith ( Irish) or flath (Modern Scottish Gaelic), plural flatha, in the Gaelic world, could refer to any member in general of a powerful family enjoying a high degree of sovereignty, and so is also sometimes tr ...

'' rince They had no political or clan rights, could neither sue nor appear as witnesses, and were not free in the matter of entering into contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to tran ...

s. They could appear in a court of justice only in the name of the ''flaith'' or other person to whom they belonged, or whom they served, or by obtaining from an aire of the tuath to which they belonged permission to sue in his name." A was defined by D. A. Binchy

Daniel Anthony Binchy (1899–1989) was a scholar of Irish linguistics and Early Irish law.

He was educated at Clongowes Wood College (1910–16), University College Dublin (UCD), and the King's Inns (1917–20), after which he was called t ...

as "a ' tenant at will,' settled by the lord (''flaith'') on a portion of the latter's land; his services to the lord are always undefined. Although his condition is servile, he retains the right to abandon his holding on giving due notice to the lord and surrendering to him two thirds of the products of his husbandry."

Poland

Serfdom in Poland became the dominant form of relationship between peasants and nobility in the 17th century, and was a major feature of the economy of thePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, although its origins can be traced back to the 12th century.

The first steps towards abolition of serfdom were enacted in the Constitution of 3 May 1791

The Constitution of 3 May 1791,; lt, Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija titled the Governance Act, was a constitution adopted by the Great Sejm ("Four-Year Sejm", meeting in 1788–1792) for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a dual mo ...

, and it was essentially eliminated by the Połaniec Manifesto. However, these reforms were partly nullified by the partition of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

. Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

had abolished serfdom in the territories he gained from the first partition of Poland. Over the course of the 19th century, it was gradually abolished on Polish and Lithuanian territories under foreign control, as the region began to industrialize

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econom ...

.

Russia

Serfdom became the dominant form of relation between Russian peasants andnobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

in the 17th century. Serfdom only existed in central and southern areas of the Russian Empire. It was never established in the North, in the Urals, and in Siberia. According to the ''Encyclopedia of Human Rights'':

Russia's over 23 million (about 38% of the total population) privately held serfs were freed from their lords by an edict of Alexander II in 1861. The owners were compensated through taxes on the freed serfs. State serf State serfs or state peasants (russian: Государственные крестьяне, gosudarstvennye krestiane) were a special social estate (class) of peasantry in 18th–19th century Russia, the number of which in some periods reached half o ...

s were emancipated in 1866.

Emancipation dates by country

* Scotland: neyfs (serfs) disappeared by the late 14th century. In the salt and coal mining industries a form of serfdom survived until the Colliers (Scotland) Act 1799.J. A. Cannon, 'Serfdom', in John Cannon (ed.), ''The Oxford Companion to British History'' (Oxford: University Press, 2002), p. 852. *England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

: obsolete by 15th–16th century,

* Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and so ...

: August 5, 1746 (land reforms in 1864)

* Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

: August 6, 1749 (land reforms in 1864)

* Savoy: 19 December 1771

* Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

: 1 November 1781 (first step; second step: 1848)

* Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

: 1 November 1781 (first step; second step: 1848)

* Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden i ...

: 23 July 1783

* Denmark: 20 June 1788 (part of Denmark-Norway)

* France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

: August 4, 1789

* Helvetic Republic: 4 May 1798

* Batavian Republic (Netherlands): constitution of 12 June 1798 (in theory; in practice with the introduction of the French Code Napoléon in 1811)

* Serbia: 1804 (''de facto'', ''de jure'' in 1830)

* Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sch ...

: 19 December 1804 (part of Denmark-Norway)

* Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

: 4 July 1806

* Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

(Poland): 22 July 1807

* Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

: 9 October 1807 (effectively 1811–1823)

* Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label= Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schweri ...

: October 1807 (effectively 1820)

* Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

: 31 August 1808

* Old Finland

Old Finland ( fi, Vanha Suomi; rus, Ста́рая Финля́ндия, r=Staraya Finlyandiya; sv, Gamla Finland) is a name used for the areas that Russia gained from Sweden in the Great Northern War (1700–1721) and in the Russo-Swedis ...

in 1812 (as the area was incorporated into Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecessor ...

where serfdom hadn't existed in centuries, if ever)

* Nassau

Nassau may refer to:

Places Bahamas

*Nassau, Bahamas, capital city of the Bahamas, on the island of New Providence

Canada

*Nassau District, renamed Home District, regional division in Upper Canada from 1788 to 1792

*Nassau Street (Winnipeg), ...

: 1 September 1812

* Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

: 18 March 1812 (first step; second step: 26 August 1837)

* Argentina: 1813

* Governorate of Estonia

The Governorate of Estonia, also known as the Governorate of Esthonia (Pre-reformed rus, Эстля́ндская губе́рнія, r=Estlyandskaya guberniya); et, Eestimaa kubermang was a governorate in the Baltic region, along with the ...

: 23 March 1816

* Governorate of Courland

The Courland Governorate, also known as the Province of Courland, Governorate of Kurland (german: Kurländisches Gouvernement; russian: Курля́ндская губерния, translit=Kurljándskaja gubernija; lv, Kurzemes guberņa; lt, K ...

: 25 August 1817

* Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Würt ...

: 18 November 1817

* Governorate of Livonia

The Governorate of Livonia, also known as the Livonia Governorate, was a Baltic governorate of the Russian Empire, now divided between Latvia and Estonia.

Geography

The shape of the province is a fairly rectangular in shape, with a maximum ...

: 26 March 1819

* Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

: 1831

* Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

: 17 March 1832

* Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

: 11 April 1848

* Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

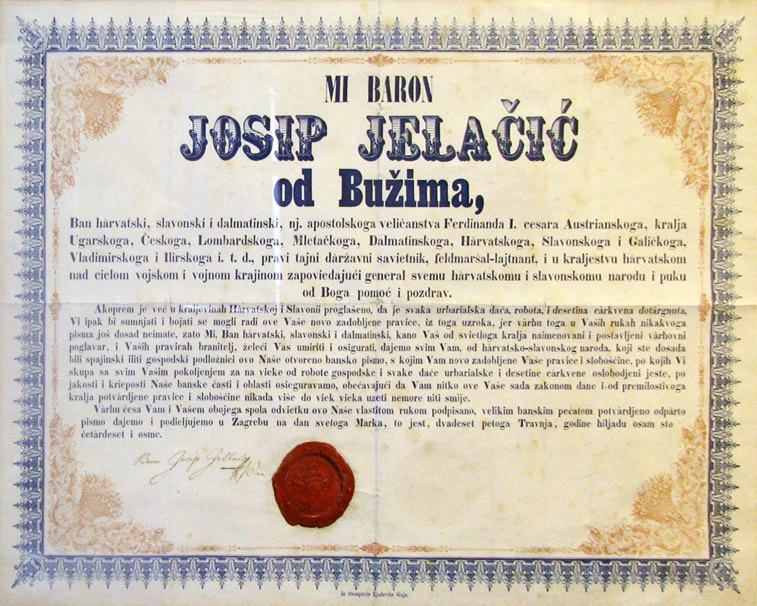

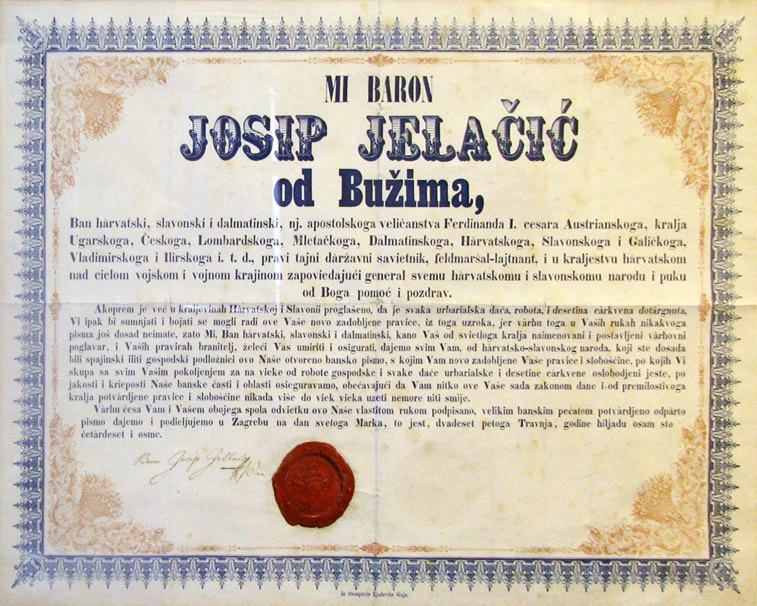

: First steps in 1780 and 1785. Final step on 8 May 1848

* Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

: 7 September 1848

* Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

: 1858 (''de jure'' by Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

; ''de facto'' in 1878)

* Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

: 19 February 1861 (''see Emancipation reform of 1861

The emancipation reform of 1861 in Russia, also known as the Edict of Emancipation of Russia, (russian: Крестьянская реформа 1861 года, translit=Krestyanskaya reforma 1861 goda – "peasants' reform of 1861") was the first ...

'')

* Tonga: 1862

* Hawaii: 1835 *

* Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

: 1864* Georgia: 1864–1871 *

Kalmykia

he official languages of the Republic of Kalmykia are the Kalmyk and Russian languages./ref>

, official_lang_list= Kalmyk

, official_lang_ref=Steppe Code (Constitution) of the Republic of Kalmykia, Article 17: he official languages of the ...

: 1892

* Iceland: 1894 (Vistarband

The Icelandic vistarband () was a requirement that all landless people be employed on a farm. A person who did not own or lease property had to find a position as a laborer (''vinnuhjú'' ) in the home of a farmer. The custom was for landless peopl ...

)

* Bosnia and Herzegovina: 1918

* Afghanistan: 1923

* Bhutan: officially abolished by 1959

* Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

, People's Republic of China: 29 March 1959, but use of "serf" for Tibet is controversial

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite ...

. There are differences depending on the region and sect.

See also

*Alipin

The ''alipin'' refers to the lowest social class among the various cultures of the Philippines before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the Visayan languages, the equivalent social classes were known as the ''oripun' ...

* Birkarls

The Birkarls (''birkarlar'' in Swedish, unhistorical ''pirkkamiehet'' or ''pirkkalaiset'' in Finnish; ''bircharlaboa'', ''bergcharl'' etc. in historical sources) were a small, unofficially organized group that controlled taxation and commerce in ...

* Colonus early Medieval serfs

* Coolie

A coolie (also spelled koelie, kuli, khuli, khulie, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a term for a low-wage labourer, typically of South Asian or East Asian descent.

The word ''coolie'' was first popularized in the 16th century by European traders acros ...

* Cottar

Cotter, cottier, cottar, or is the German or Scots term for a peasant farmer (formerly in the Scottish Highlands for example). Cotters occupied cottages and cultivated small land lots. The word ''cotter'' is often employed to translate th ...

* Encomienda Spanish serfdom transplanted to the Americas

* Feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

* Fiefdom

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of f ...

* Folwark

''Folwark''; german: Vorwerk; uk, Фільварок; ''Filwarok''; be, Фальварак; ''Falwarak''; lt, Palivarkas is a Polish word for a primarily serfdom-based farm and agricultural enterprise (a type of ''latifundium''), often very ...

* Freeholder

* Fugitive peasants Fugitive peasants (also runaway peasants, or flight of peasants) are peasants who left their land without permission, violating serfdom laws. Under serfdom, peasants usually required permission to leave the land they lived on.

Running away was seen ...

* Hacienda Spanish manors

* Helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their e ...

ancient Greek serfs

* Indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repaymen ...

* Josephinism

Josephinism was the collective domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms ...

* Kholop

A kholop ( rus, холо́п, p=xɐˈlop) was a type of feudal serf in Kievan Rus', then in Russia between the 10th and early 18th centuries. Their legal status was close to that of slaves.

Etymology

The word ''kholop'' was first mentioned in ...

* Kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz., a contraction of советское хозяйство, soviet ownership or ...

* Maenor

The maenor (pl. ''maenorau'') was a gathering of villages in medieval Wales. In North Wales the word ''maenol'' was used for a similar, but not identical, idea.

Although it is very often conflated with the English manor, ''maenor'' predates that ...

Welsh manors

* Manorialism

Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes forti ...

* Ministerialis

The ''ministeriales'' (singular: ''ministerialis'') were a class of people raised up from serfdom and placed in positions of power and responsibility in the High Middle Ages in the Holy Roman Empire.

The word and its German translations, ''Minis ...

* Peonage

Peon ( English , from the Spanish ''peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over em ...

* Russian serfdom

The term '' serf'', in the sense of an unfree peasant of tsarist Russia, is the usual English-language translation of () which meant an unfree person who, unlike a slave, historically could be sold only with the land to which they were "att ...

* Serfdom Patent

* Serfdom in Tibet controversy

The serfdom in Tibet controversy is a prolonged public disagreement over the extent and nature of serfdom in Tibet prior to the annexation of Tibet into the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1951. The debate is political in nature, with some ...

* Serfs Emancipation Day

Serfs' Emancipation Day, observed annually on 28 March, is a holiday in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China that celebrates the emancipation of serfs in Tibet. The holiday was adopted by the Tibetan legislature on 19 January 2009, and was pr ...

* Sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

* Shōen Japanese serfdom

* Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

* Smerd

* Subjugate Subjugate or subjugation is the action of enslaving using force or coercion on other humans. It could include forced labour such as slavery, serfdom, Penal labour, Labor camps; or paid voluntary labor that is involuntarily taxed leading to parti ...

* Taeog

A taeog (pl. ''taeogion''; Latin: ''villanus'') was a native serf or villein of the medieval Welsh kingdoms. The term was used in south Wales and literally denoted someone "belonging to the house" (''ty'') of the lord's manor. The equivalent term ...

Welsh serfs

* Taxation as theft

The position that taxation is theft, and therefore immoral, is found in a number of political philosophies considered radical. It marks a significant departure from conservatism and classical liberalism. This position is often held by anarcho- ...

* Thrall

A thrall ( non, þræll, is, þræll, fo, trælur, no, trell, træl, da, træl, sv, träl) was a slave or serf in Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The corresponding term in Old English was . The status of slave (, ) contrasts wi ...

* Yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

English freeholders

* Ritsuryō

, , is the historical law system based on the philosophies of Confucianism and Chinese Legalism in Japan. The political system in accord to Ritsuryō is called "Ritsuryō-sei" (律令制). ''Kyaku'' (格) are amendments of Ritsuryō, ''Shiki'' ...

* Fengjian

''Fēngjiàn'' ( zh, c=封建, l=enfeoffment and establishment) was a political ideology and governance system in ancient China, whose social structure formed a decentralized system of confederation-like government based on the ruling class consis ...

References

Further reading

* Backman, Clifford R. ''The Worlds of Medieval Europe'' Oxford University Press, 2003. * Blum, Jerome. ''The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe'' (Princeton UP, 1978) * Coulborn, Rushton, ed. ''Feudalism in History''. Princeton University Press, 1956. * Bonnassie, Pierre. ''From Slavery to Feudalism in South-Western Europe'' Cambridge University Press, 199excerpt and text search

* Freedman, Paul, and Monique Bourin, eds. ''Forms of Servitude in Northern and Central Europe. Decline, Resistance and Expansion'' Brepols, 2005. * Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat, eds. ''The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England''. Glasgow: Cruithne P, 1994. * Gorshkov, Boris B. "Serfdom: Eastern Europe" in Peter N. Stearns, ed, ''Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000'' (2001) volume 2 pp. 379–88 * Hoch, Steven L. ''Serfdom and social control in Russia: Petrovskoe, a village in Tambov'' (1989) * Kahan, Arcadius. "Notes on Serfdom in Western and Eastern Europe," ''Journal of Economic History'' March 1973 33:86–9

in JSTOR

* Kolchin, Peter. ''Unfree labor: American slavery and Russian serfdom'' (2009) * Moon, David. ''The abolition of serfdom in Russia 1762–1907'' (Longman, 2001) * Scott, Tom, ed. ''The Peasantries of Europe'' (1998) * Vadey, Liana. "Serfdom: Western Europe" in Peter N. Stearns, ed, ''Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000'' (2001) volume 2 pp. 369–78 * White, Stephen D. ''Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe'' (2nd ed. Ashgate Variorum, 2000) * Wirtschafter, Elise Kimerling. ''Russia's age of serfdom 1649–1861'' (2008) * Wright, William E. ''Serf, Seigneur, and Sovereign: Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-century Bohemia'' (U of Minnesota Press, 1966). * Wunder, Heide. "Serfdom in later medieval and early modern Germany" in T. H. Aston et al., ''Social Relations and Ideas: Essays in Honour of R. H. Hilton'' (Cambridge UP, 1983), 249–72

External links

Serfdom

''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'' (on-line edition).

The Hull Project

''

Hull University

, mottoeng = Bearing the Torch f learning, established = 1927 – University College Hull1954 – university status

, type = Public

, endowment = £18.8 million (2016)

, budget = £190 million ...

''

*

Peasantry (social class)

''Encyclopædia Britannica''.

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20030514164951/http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/movable_type/2003_archives/001447.html The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis discussion and full online text of

Evsey Domar

Evsey David Domar (russian: Евсей Давидович Домашевицкий, ''Domashevitsky''; April 16, 1914 – April 1, 1997) was a Russian American economist, famous as developer of the Harrod–Domar model.

Life

Evsey Domar was bor ...

(1970), "The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis", ''Economic History Review

''The Economic History Review'' is a peer-reviewed history journal published quarterly by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Economic History Society. It was established in 1927 by Eileen Power and is currently edited by Sara Horrell, Jaime Reis an ...

'' 30:1 (March), pp. 18–32.

{{Authority control

3rd-century establishments in the Roman Empire

1894 disestablishments in Iceland

Agricultural labor

Debt bondage

Feudalism

Indentured servitude

Late antiquity

Peasants

Social classes

Slavery by type