Booker T. Washington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several

Accessed March 10, 2008 African Americans were still strongly affiliated with the

Booker was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved

Booker was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved

In 1881, the Hampton Institute president

In 1881, the Hampton Institute president  The Oaks, "a large comfortable home," was built on campus for Washington and his family."The Oaks"

The Oaks, "a large comfortable home," was built on campus for Washington and his family."The Oaks"

Tuskegee Museum, National Park Service They moved into the house in 1900. Washington lived there until his death in 1915. His widow, Margaret, lived at The Oaks until her death in 1925.

Washington was a dominant figure of the African-American community, then still overwhelmingly based in the South, from 1890 to his death in 1915. His Atlanta Address of 1895 received national attention. He was considered as a popular spokesman for African-American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, Washington was generally perceived as a supporter of education for freedmen and their descendants in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow-era South. He stressed basic education and training in manual and

Washington was a dominant figure of the African-American community, then still overwhelmingly based in the South, from 1890 to his death in 1915. His Atlanta Address of 1895 received national attention. He was considered as a popular spokesman for African-American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, Washington was generally perceived as a supporter of education for freedmen and their descendants in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow-era South. He stressed basic education and training in manual and

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography '' Up from Slavery'', he gave all three of his wives credit for their contributions at Tuskegee. His first wife Fannie N. Smith was from

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography '' Up from Slavery'', he gave all three of his wives credit for their contributions at Tuskegee. His first wife Fannie N. Smith was from

Well-educated blacks in the North lived in a different society and advocated a different approach, in part due to their perception of wider opportunities. Du Bois wanted blacks to have the same "classical"

Well-educated blacks in the North lived in a different society and advocated a different approach, in part due to their perception of wider opportunities. Du Bois wanted blacks to have the same "classical"

State and local governments historically underfunded black schools, although they were ostensibly providing "separate but equal" segregated facilities. White philanthropists strongly supported education financially. Washington encouraged them and directed millions of their money to projects all across the South that Washington thought best reflected his self-help philosophy. Washington associated with the richest and most powerful businessmen and politicians of the era. He was seen as a spokesperson for African Americans and became a conduit for funding educational programs.

His contacts included such diverse and well known entrepreneurs and philanthropists as

State and local governments historically underfunded black schools, although they were ostensibly providing "separate but equal" segregated facilities. White philanthropists strongly supported education financially. Washington encouraged them and directed millions of their money to projects all across the South that Washington thought best reflected his self-help philosophy. Washington associated with the richest and most powerful businessmen and politicians of the era. He was seen as a spokesperson for African Americans and became a conduit for funding educational programs.

His contacts included such diverse and well known entrepreneurs and philanthropists as

A representative case of an exceptional relationship was Washington's friendship with millionaire industrialist and financier

A representative case of an exceptional relationship was Washington's friendship with millionaire industrialist and financier

Washington's long-term adviser,

Washington's long-term adviser,

Despite his extensive travels and widespread work, Washington continued as principal of Tuskegee. Washington's health was deteriorating rapidly in 1915; he collapsed in New York City and was diagnosed by two different doctors as having

Despite his extensive travels and widespread work, Washington continued as principal of Tuskegee. Washington's health was deteriorating rapidly in 1915; he collapsed in New York City and was diagnosed by two different doctors as having

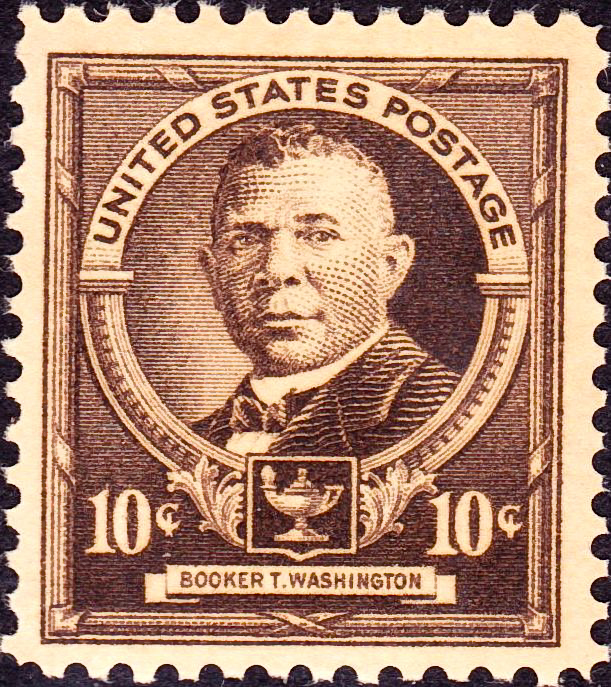

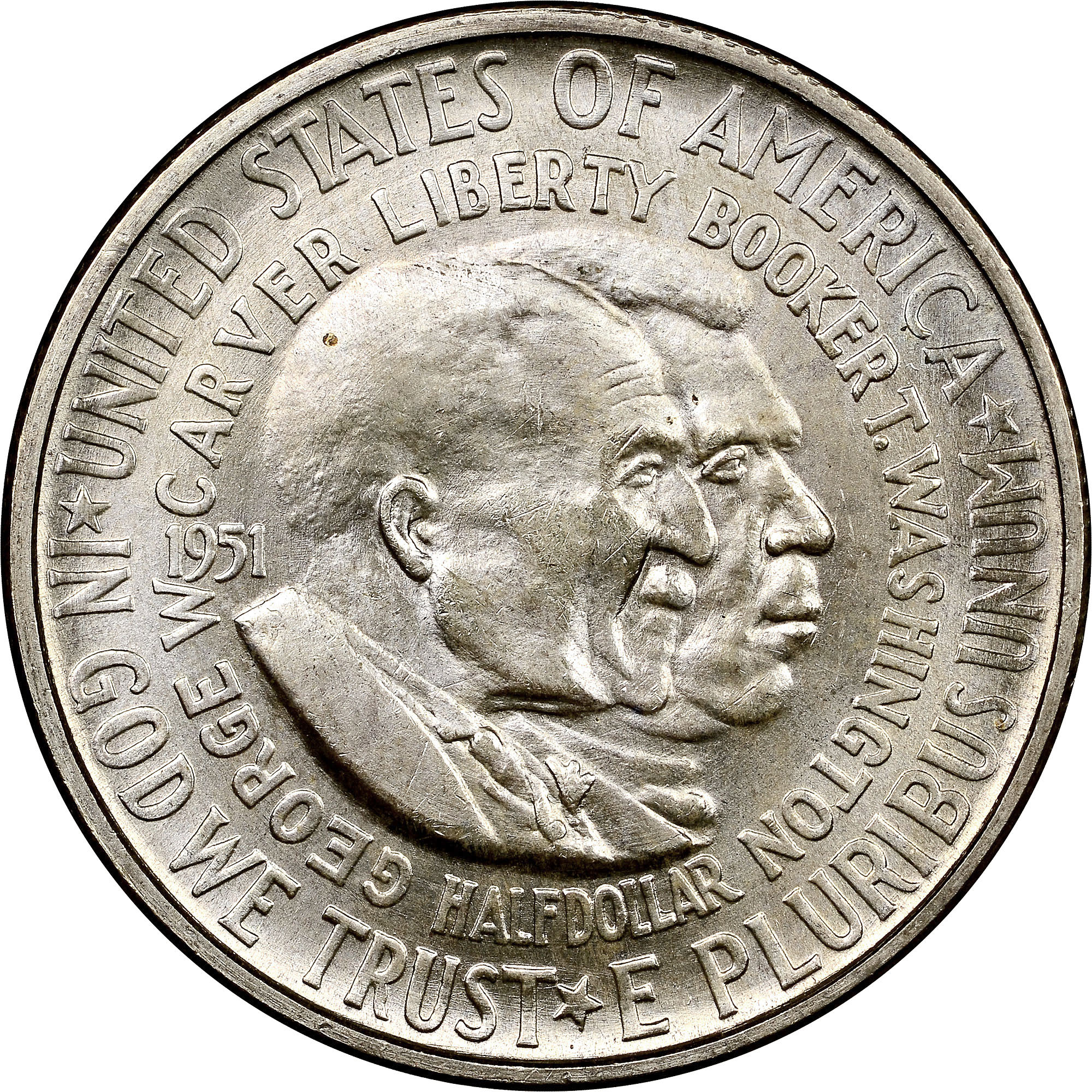

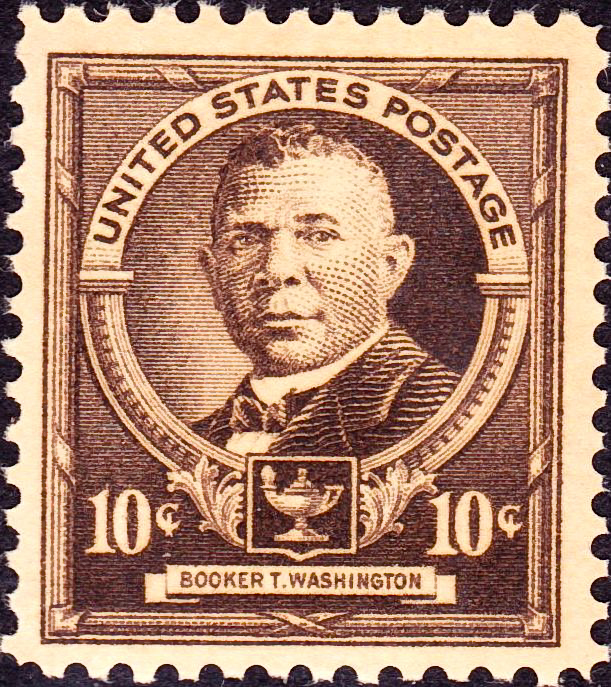

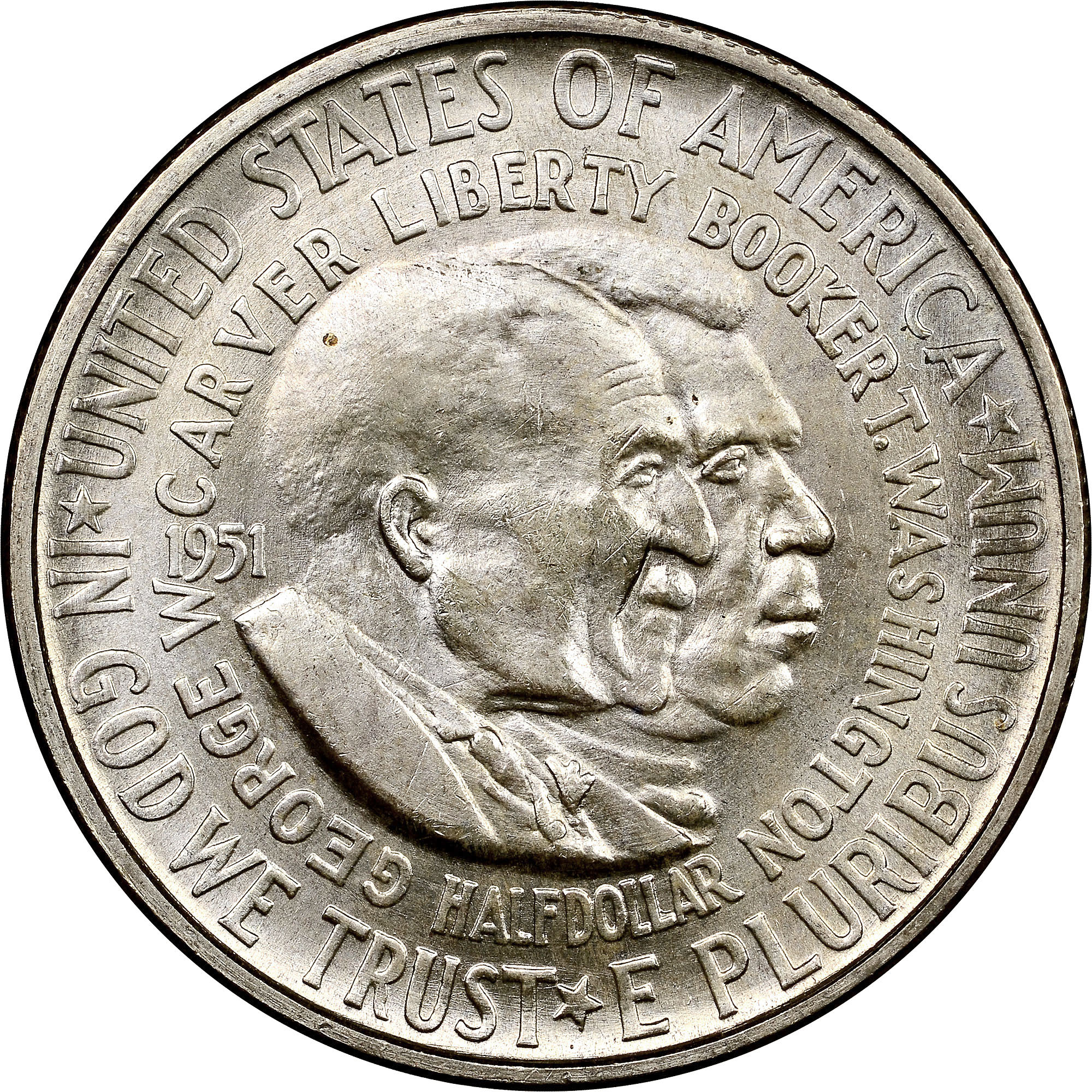

For his contributions to American society, Washington was granted an honorary

For his contributions to American society, Washington was granted an honorary  In 1942, the

In 1942, the

Booker T. Washington was so acclaimed as a public leader that the period of his activity, from 1880 to 1915, has been called the Age of Booker T. Washington. Historiography on Washington, his character, and the value of that leadership has varied dramatically. After his death, he came under heavy criticism in the civil rights community for accommodationism to white supremacy. However, since the late 20th century, a more balanced view of his very wide range of activities has appeared. As of 2010, the most recent studies, "defend and celebrate his accomplishments, legacy, and leadership".

Washington was held in high regard by business-oriented conservatives, both white and black. Historian

Booker T. Washington was so acclaimed as a public leader that the period of his activity, from 1880 to 1915, has been called the Age of Booker T. Washington. Historiography on Washington, his character, and the value of that leadership has varied dramatically. After his death, he came under heavy criticism in the civil rights community for accommodationism to white supremacy. However, since the late 20th century, a more balanced view of his very wide range of activities has appeared. As of 2010, the most recent studies, "defend and celebrate his accomplishments, legacy, and leadership".

Washington was held in high regard by business-oriented conservatives, both white and black. Historian

Online

ref>

Project Gutenberg

* * * * * * * * * * Fourteen-volume set of all letters to and from Booker T. Washington. ** **

online

"Booker T. Washington: The Man and the Myth Revisited." (2007) PowerPoint presentation By Dana Chandler

* * * , index to over 300,000 items related to Washington available at the Library of Congress and on microfilm. *

"Writings of Writings of B. Washington and Du Bois"

from

Booker T. Washington

historical marker in Piedmont Park, Atlanta, Georgia * * Booker T. Washington Papers Editorial Project collection at the

presidents of the United States

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government and ...

. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary black elite

The Black elite is any elite, either political or economic in nature, that is made up of people who identify as of Black African descent. In the Western World, it is typically distinct from other national elites, such as the United Kingdom's arist ...

. Washington was from the last generation of black American leaders born into slavery and became the leading voice of the former slaves and their descendants. They were newly oppressed in the South by disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

and the Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

discriminatory laws enacted in the post-Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

Southern states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Washington was a key proponent of African-American businesses and one of the founders of the National Negro Business League

The National Negro Business League (NNBL) was an American organization founded in Boston in 1900 by Booker T. Washington to promote the interests of African-American businesses. The mission and main goal of the National Negro Business League was ...

. His base was the Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

, a normal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to Teacher education, train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high s ...

, later a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

in Tuskegee, Alabama

Tuskegee () is a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. It was founded and laid out in 1833 by General Thomas Simpson Woodward, a Creek War veteran under Andrew Jackson, and made the county seat that year. It was incorporated in 1843. ...

, at which he served as principal. As lynchings

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

in the South reached a peak in 1895, Washington gave a speech, known as the " Atlanta compromise", that brought him national fame. He called for black progress through education and entrepreneurship, rather than trying to challenge directly the Jim Crow segregation and the disenfranchisement of black voters in the South.

Washington mobilized a nationwide coalition of middle-class blacks, church leaders, and white philanthropists and politicians, with a long-term goal of building the community's economic strength and pride by a focus on self-help and schooling. With his own contributions to the black community, Washington was a supporter of racial uplift Racial uplift is a term within the African American community that motivates educated blacks to be responsible in the lifting of their race. This concept traced back to the late 1800s, introduced by black elites, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. ...

, but, secretly, he also supported court challenges to segregation and to restrictions on voter registration.

Washington had the ear of the powerful in the America of his day, including presidents. His mastery of the American political system in the later 19th century allowed him to manipulate the media, raise money, develop strategy, network, distribute funds, and reward a cadre

Cadre may refer to:

*Cadre (military), a group of officers or NCOs around whom a unit is formed, or a training staff

*Cadre (politics), a politically controlled appointment to an institution in order to circumvent the state and bring control to th ...

of supporters. Because of his influential leadership, the timespan of his activity, from 1880 to 1915, has been called the Age of Booker T. Washington. Nevertheless, opposition to Washington grew, as it became clear that his Atlanta compromise did not produce the promised improvement for most black Americans in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

. William Monroe Trotter

William Monroe Trotter, sometimes just Monroe Trotter (April 7, 1872 – April 7, 1934), was a newspaper editor and real estate businessman based in Boston, Massachusetts. An activist for African-American civil rights, he was an early opponent of ...

and W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

, whom Bookerites perceived in an antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

way as "northern blacks", found Washington too accommodationist and his industrial ("agricultural and mechanical") education inadequate. Washington fought vigorously against them and succeeded in his opposition to the Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. ...

that they tried to found but could not prevent their formation of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, whose views became mainstream.

Black activists in the North, led by Du Bois, at first supported the Atlanta compromise, but later disagreed and opted to set up the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP) to work for political change. They tried with limited success to challenge Washington's political machine for leadership in the black community, but built wider networks among white allies in the North. Decades after Washington's death in 1915, the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

of the 1950s took a more active and progressive approach, which was also based on new grassroots organizations based in the South, such as Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission ...

(CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

(SNCC) and Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

(SCLC).

Washington's legacy has been controversial in the civil rights community. After his death in 1915, he came under heavy criticism for accommodationism to white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

, despite his claims that his long-term goal was to end the disenfranchisement of African Americans, the vast majority of whom still lived in the South. However, a more neutral view has appeared since the late 20th century. As of 2010, most recent studies "defend and celebrate his accomplishments, legacy, and leadership".

Overview

In 1856, Washington was born into slavery inVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

as the son of Jane, an African-American slave. After emancipation, she moved the family to West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

to join her husband, Washington Ferguson. West Virginia had seceded from Virginia and joined the Union as a free state during the Civil War. As a young man, Booker T. Washington worked his way through Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

, now Hampton University

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association af ...

) and attended college at Wayland Seminary Wayland Seminary was the Washington, D.C. school of the National Theological Institute. The institute was established beginning in 1865 by the American Baptist Home Mission Society (ABHMS). At first designed primarily for providing education and tra ...

(now Virginia Union University

Virginia Union University is a private historically black Baptist university in Richmond, Virginia. It is affiliated with the American Baptist Churches USA.

History

The American Baptist Home Mission Society (ABHMS) founded the school as Richm ...

).

In 1881, the young Washington was named as the first leader of the new Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

in Alabama, founded for the higher education of blacks. He developed the college from the ground up, enlisting students in construction of buildings, from classrooms to dormitories. Work at the college was considered fundamental to students' larger education. They maintained a large farm to be essentially self-supporting, rearing animals and cultivating needed produce. Washington continued to expand the school. He attained national prominence for his Atlanta Address of 1895, which attracted the attention of politicians and the public. He became a popular spokesperson for African-American citizens. He built a nationwide network of supporters in many black communities, with black ministers, educators, and businessmen composing his core supporters. Washington played a dominant role in black politics, winning wide support in the black community of the South and among more liberal whites (especially rich Northern whites). He gained access to top national leaders in politics, philanthropy and education. Washington's efforts included cooperating with white people and enlisting the support of wealthy philanthropists. Washington had asserted that the surest way for blacks to gain equal social rights was to demonstrate "industry, thrift, intelligence and property".

Beginning in 1912, he developed a relationship with philanthropist Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions in ...

, the owner of Sears Roebuck

Sears, Roebuck and Co. ( ), commonly known as Sears, is an American chain of department stores founded in 1892 by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck and reincorporated in 1906 by Richard Sears and Julius Rosenwald, with what began a ...

, who served on the board of trustees for the rest of his life and made substantial donations to Tuskegee. In addition, they collaborated on a pilot program for Tuskegee architects to design six model schools for African-American students in rural areas of the South. Such schools were historically underfunded by the state and local governments. Given their success in 1913 and 1914, Rosenwald established the Rosenwald Foundation

The Rosenwald Fund (also known as the Rosenwald Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, and the Julius Rosenwald Foundation) was established in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald and his family for "the well-being of mankind." Rosenwald became part-owner of S ...

in 1917 to aid schools. It provided matching funds to communities that committed to operate the schools and for the construction and maintenance of schools, with cooperation of white public school boards required. Nearly 5,000 new, small rural schools were built for black students throughout the South, most after Washington's death in 1915.

Northern critics called Washington's widespread and powerful organization the "Tuskegee Machine". After 1909, Washington was criticized by the leaders of the new NAACP, especially W. E. B. Du Bois, who demanded a stronger tone of protest in order to advance the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

agenda. Washington replied that confrontation would lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks in society, and that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way to overcome pervasive racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

in the long run. At the same time, he secretly funded litigation for civil rights cases, such as challenges to Southern constitutions and laws that had disenfranchised blacks across the South since the turn of the century.Richard H. Pildes, Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon, ''Constitutional Commentary'', vol. 17, 2000, pp. 13–14Accessed March 10, 2008 African Americans were still strongly affiliated with the

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

, and Washington was on close terms with national Republican Party leaders. He was often asked for political advice by presidents Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

.

In addition to his contributions to education, Washington wrote 14 books; his autobiography, '' Up from Slavery,'' first published in 1901, is still widely read today. During a difficult period of transition, he did much to improve the working relationship between the races. His work greatly helped blacks to achieve education, financial power, and understanding of the U.S. legal system. This contributed to blacks' attaining the skills to create and support the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, leading to the passage in the later 20th century of important federal civil rights laws.

Early life

Booker was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved

Booker was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

woman on the plantation of James Burroughs in southwest Virginia, near Hale's Ford in Franklin County. He never knew the day, month, and year of his birth (although evidence emerged after his death that he was born on April 5, 1856). Nor did he ever know his father, said to be a white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

man who resided on a neighboring plantation. The man played no financial or emotional role in Washington's life.

From his earliest years, Washington was known simply as "Booker", with no middle or surname, in the practice of the time. His mother, her relatives and his siblings struggled with the demands of slavery. He later wrote:

I cannot remember a single instance during my childhood or early boyhood when our entire family sat down to the table together, and God's blessing was asked, and the family ate a meal in a civilized manner. On the plantation in Virginia, and even later, meals were gotten to the children very much as dumb animals get theirs. It was a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there. It was a cup of milk at one time and some potatoes at another.When he was nine, Booker and his family in Virginia gained freedom under the

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

as U.S. troops occupied their region. Booker was thrilled by the formal day of their emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchis ...

in early 1865:

As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom.... me man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.After emancipation Jane took her family to the free state of West Virginia to join her husband, Washington Ferguson, who had escaped from slavery during the war and settled there. The illiterate boy Booker began painstakingly to teach himself to read and attended school for the first time. At school, Booker was asked for a surname for registration. He took the family name of Washington, after his stepfather. Still later he learned from his mother that she had originally given him the name "Booker

Taliaferro

Taliaferro ( ), also spelled Talliaferro, Tagliaferro, Talifero, or Taliferro and sometimes anglicised to Tellifero, Tolliver or Toliver, is a prominent family in eastern Virginia and Maryland. The Taliaferros (originally , which means "ironcutt ...

" at the time of his birth, but his second name was not used by the master. Upon learning of his original name, Washington immediately readopted it as his own, and became known as Booker Taliaferro Washington for the rest of his life.

Booker loved books:

Higher education

Washington worked in salt furnaces and coal mines in West Virginia for several years to earn money. He made his way east toHampton Institute

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association af ...

, a school established in Virginia to educate freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

and their descendants, where he also worked to pay for his studies. He later attended Wayland Seminary Wayland Seminary was the Washington, D.C. school of the National Theological Institute. The institute was established beginning in 1865 by the American Baptist Home Mission Society (ABHMS). At first designed primarily for providing education and tra ...

in Washington, D.C. in 1878.

Tuskegee Institute

In 1881, the Hampton Institute president

In 1881, the Hampton Institute president Samuel C. Armstrong

Samuel Chapman Armstrong (January 30, 1839 – May 11, 1893) was an American soldier and general during the American Civil War who later became an educator, particularly of non-whites. The son of missionaries in Hawaii, he rose through the Union A ...

recommended Washington, then age 25, to become the first leader of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (later Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University), the new normal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to Teacher education, train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high s ...

(teachers' college) in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. The new school opened on July 4, 1881, initially using a room donated by Butler Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church.

The next year, Washington purchased a former plantation to be developed as the permanent site of the campus. Under his direction, his students literally built their own school: making bricks, constructing classrooms, barns and outbuildings; and growing their own crops and raising livestock; both for learning and to provide for most of the basic necessities. Both men and women had to learn trades as well as academics. The Tuskegee faculty used all the activities to teach the students basic skills to take back to their mostly rural black communities throughout the South. The main goal was not to produce farmers and tradesmen, but teachers of farming and trades who could teach in the new lower schools and colleges for blacks across the South. The school expanded over the decades, adding programs and departments, to become the present-day Tuskegee University.

The Oaks, "a large comfortable home," was built on campus for Washington and his family."The Oaks"

The Oaks, "a large comfortable home," was built on campus for Washington and his family."The Oaks"Tuskegee Museum, National Park Service They moved into the house in 1900. Washington lived there until his death in 1915. His widow, Margaret, lived at The Oaks until her death in 1925.

Later career

Washington led Tuskegee for more than 30 years after becoming its leader. As he developed it, adding to both the curriculum and the facilities on the campus, he became a prominent national leader among African Americans, with considerable influence with wealthy white philanthropists and politicians. Washington expressed his vision for his race through the school. He believed that by providing needed skills to society, African Americans would play their part, leading to acceptance by white Americans. He believed that blacks would eventually gain full participation in society by acting as responsible, reliable American citizens. Shortly after theSpanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and most of his cabinet visited Booker Washington. By his death in 1915, Tuskegee had grown to encompass more than 100 well equipped buildings, roughly 1,500 students, 200 faculty members teaching 38 trades and professions, and an endowment of approximately $2 million.

Washington helped develop other schools and colleges. In 1891 he lobbied the West Virginia legislature to locate the newly authorized West Virginia Colored Institute

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a public historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, it is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges and universities e ...

(today West Virginia State University

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a public historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, it is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges and universities ...

) in the Kanawha Valley

The Kanawha River ( ) is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi (156 km) long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, its valley has been a significant industrial region of the stat ...

of West Virginia near Charleston. He visited the campus often and spoke at its first commencement exercise.

Washington was a dominant figure of the African-American community, then still overwhelmingly based in the South, from 1890 to his death in 1915. His Atlanta Address of 1895 received national attention. He was considered as a popular spokesman for African-American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, Washington was generally perceived as a supporter of education for freedmen and their descendants in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow-era South. He stressed basic education and training in manual and

Washington was a dominant figure of the African-American community, then still overwhelmingly based in the South, from 1890 to his death in 1915. His Atlanta Address of 1895 received national attention. He was considered as a popular spokesman for African-American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, Washington was generally perceived as a supporter of education for freedmen and their descendants in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow-era South. He stressed basic education and training in manual and domestic labor

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

trades because he thought these represented the skills needed in what was still a rural economy.

Throughout the final twenty years of his life, he maintained his standing through a nationwide network of supporters including black educators, ministers, editors, and businessmen, especially those who supported his views on social and educational issues for blacks. He also gained access to top national white leaders in politics, philanthropy and education, raised large sums, was consulted on race issues, and was awarded honorary degrees from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in 1896 and Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native A ...

in 1901.

Late in his career, Washington was criticized by civil rights leader and NAACP founder W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta Address as the "Atlanta Compromise", because it suggested that African Americans should work for, and submit to, white political rule. Du Bois insisted on full civil rights, due process of law, and increased political representation for African Americans which, he believed, could only be achieved through activism and higher education for African Americans. He believed that "the talented Tenth" would lead the race. Du Bois labeled Washington, "the Great Accommodator." Washington responded that confrontation could lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks, and that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way to overcome racism in the long run.

While promoting moderation, Washington contributed secretly and substantially to mounting legal challenges activist African Americans launched against segregation and disenfranchisement of blacks. In his public role, he believed he could achieve more by skillful accommodation to the social realities of the age of segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

.

Washington's work on education helped him enlist both the moral and substantial financial support of many major white philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

s. He became a friend of such self-made men as Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was an American industrialist and financier. He made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil. He also played a major role in numerous corporations a ...

; Sears, Roebuck and Company President Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions in ...

; and George Eastman

George Eastman (July 12, 1854March 14, 1932) was an American entrepreneur who founded the Kodak, Eastman Kodak Company and helped to bring the photographic use of roll film into the mainstream. He was a major philanthropist, establishing the ...

, inventor of roll film, founder of Eastman Kodak

The Eastman Kodak Company (referred to simply as Kodak ) is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in analogue photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorpor ...

, and developer of a major part of the photography industry. These individuals and many other wealthy men and women funded his causes, including Hampton and Tuskegee institutes.

He also gave lectures to raise money for the school. On January 23, 1906, he lectured at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

in New York in the Tuskegee Institute Silver Anniversary Lecture

The Tuskegee Institute Silver Anniversary Lecture was an event at Carnegie Hall on January 23, 1906, to support the education of African Americans in the South. It involved many prominent members of New York society, with speakers including Book ...

. He spoke along with great orators of the day, including Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

, Joseph Hodges Choate

Joseph Hodges Choate (January 24, 1832 – May 14, 1917) was an American lawyer and diplomat. Choate was associated with many of the most famous litigations in American legal history, including the Kansas prohibition cases, the Chinese exclusi ...

, and Robert Curtis Ogden

Robert Curtis Ogden (June 20, 1836 – August 6, 1913) was a businessman who promoted education in the Southern United States.

Biography

Ogden was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 20, 1836. He began work in a dry-goods store at 14 years ...

; it was the start of a capital campaign to raise $1,800,000 for the school.

The schools which Washington supported were founded primarily to produce teachers, as education was critical for the black community following emancipation. Freedmen strongly supported literacy and education as the keys to their future. When graduates returned to their largely impoverished rural southern communities, they still found few schools and educational resources, as the white-dominated state legislatures consistently underfunded black schools in their segregated system.

To address those needs, in the 20th century, Washington enlisted his philanthropic network to create matching funds programs to stimulate construction of numerous rural public schools for black children in the South. Working especially with Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions in ...

from Chicago, Washington had Tuskegee architects develop model school designs. The Rosenwald Fund

The Rosenwald Fund (also known as the Rosenwald Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, and the Julius Rosenwald Foundation) was established in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald and his family for "the well-being of mankind." Rosenwald became part-owner of S ...

helped support the construction and operation of more than 5,000 schools and related resources for the education of blacks throughout the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The local schools were a source of communal pride; African-American families gave labor, land and money to them, to give their children more chances in an environment of poverty and segregation. A major part of Washington's legacy, the model rural schools continued to be constructed into the 1930s, with matching funds for communities from the Rosenwald Fund

The Rosenwald Fund (also known as the Rosenwald Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, and the Julius Rosenwald Foundation) was established in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald and his family for "the well-being of mankind." Rosenwald became part-owner of S ...

.

Washington also contributed to the Progressive Era by forming the National Negro Business League. It encouraged entrepreneurship among black businessmen, establishing a national network.

His autobiography, '' Up from Slavery,'' first published in 1901, is still widely read in the early 21st century.

Marriages and children

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography '' Up from Slavery'', he gave all three of his wives credit for their contributions at Tuskegee. His first wife Fannie N. Smith was from

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography '' Up from Slavery'', he gave all three of his wives credit for their contributions at Tuskegee. His first wife Fannie N. Smith was from Malden, West Virginia

Malden — originally called Kanawha Salines — is an unincorporated community in Kanawha County, West Virginia, United States, within the Charleston metro area.

History

The Kanawha Saline(s) post office was established in 1814 and discontinued ...

, the same Kanawha River

The Kanawha River ( ) is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi (156 km) long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, its valley has been a significant industrial region of the stat ...

Valley town where Washington had lived from age nine to sixteen. He maintained ties there all his life, and Smith was a student of his when he taught in Malden. He helped her gain entrance into the Hampton Institute. Washington and Smith were married in the summer of 1882, a year after he became principal there. They had one child, Portia M. Washington, born in 1883. Fannie died in May 1884.

In 1885, the widower Washington married again, to Olivia A. Davidson

Olivia America Davidson Washington (June 11, 1854 – May 9, 1889) was an American teacher and educator.

She was born free as Olivia America Davidson in Virginia. After her family moved to the free state of Ohio, she studied in common schools ...

(1854–1889). Born free in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

to a free woman of color and a father who had been freed from slavery, she moved with her family to the free state of Ohio, where she attended common schools. Davidson later studied at Hampton Institute and went North to study at the Massachusetts State Normal School at Framingham

Framingham () is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The city proper covers with a popul ...

. She taught in Mississippi and Tennessee before going to Tuskegee to work as a teacher. Washington recruited Davidson to Tuskegee, and promoted her to vice-principal. They had two sons, Booker T. Washington Jr. and Ernest Davidson Washington, before she died in 1889.

In 1893, Washington married Margaret James Murray

Margaret Murray Washington (March 9, 1865 - June 4, 1925) was an American educator who was the principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, which later became Tuskegee University. She also led women’s clubs. She was the third wife ...

. She was from Mississippi and had graduated from Fisk University

Fisk University is a private historically black liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1930, Fisk was the first Africa ...

, a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

. They had no children together, but she helped rear Washington's three children. Murray outlived Washington and died in 1925.

Politics and the Atlanta compromise

Washington's 1895Atlanta Exposition

The Atlanta Exposition Speech was an address on the topic of race relations given by African-American scholar Booker T. Washington on September 18, 1895. The speech, presented before a predominantly white audience at the Cotton States and In ...

address

An address is a collection of information, presented in a mostly fixed format, used to give the location of a building, apartment, or other structure or a plot of land, generally using political boundaries and street names as references, along w ...

was viewed as a "revolutionary moment" by both African Americans and whites across the country. At the time W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

supported him, but they grew apart as Du Bois sought more action to remedy disfranchisement and improve educational opportunities for blacks. After their falling out, Du Bois and his supporters referred to Washington's speech as the "Atlanta Compromise" to express their criticism that Washington was too accommodating to white interests.

Washington advocated a "go slow" approach to avoid a harsh white backlash. He has been criticized for encouraging many youths in the South to accept sacrifices of potential political power, civil rights, and higher education. Washington believed that African Americans should "concentrate all their energies on industrial education, and accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South". He valued the "industrial" education, as it provided critical skills for the jobs then available to the majority of African Americans at the time, as most lived in the South, which was overwhelmingly rural and agricultural. He thought these skills would lay the foundation for the creation of stability that the African-American community required in order to move forward. He believed that in the long term, "blacks would eventually gain full participation in society by showing themselves to be responsible, reliable American citizens". His approach advocated for an initial step toward equal rights, rather than full equality under the law, gaining economic power to back up black demands for political equality in the future. He believed that such achievements would prove to the deeply prejudiced white America that African Americans were not "'naturally' stupid and incompetent".

liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the ...

education as upper-class whites did, along with voting rights and civic equality. The latter two had been ostensibly granted since 1870 by constitutional amendments after the Civil War. He believed that an elite, which he called the Talented Tenth, would advance to lead the race to a wider variety of occupations. Du Bois and Washington were divided in part by differences in treatment of African Americans in the North versus the South; although both groups suffered discrimination, the mass of blacks in the South were far more constrained by legal segregation and disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

, which totally excluded most from the political process and system. Many in the North objected to being 'led', and authoritatively spoken for, by a Southern accommodationist strategy which they considered to have been "imposed on them outhern blacksprimarily by Southern whites".

Historian Clarence Earl Walker

Clarence Earl Walker is an American historian and Distinguished Professor (Emeritus) in the Department of History at the University of California, Davis. He earned bachelor's and master's degrees from San Francisco State University and a doctorate ...

wrote that, for white Southerners

White Southerners, from the Southern United States, are considered an ethnic group by some historians, sociologists and journalists, although this categorization has proven controversial, and other academics have argued that Southern identity does ...

,

Free black people were 'matter out of place'. Their emancipation was an affront to southern white freedom. Booker T. Washington did not understand that his program was perceived as subversive of a natural order in which black people were to remain forever subordinate or unfree.Both Washington and Du Bois sought to define the best means post-Civil War to improve the conditions of the African-American community through education. Blacks were solidly

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

in this period, having gained emancipation and suffrage with President Lincoln and his party. Fellow Republican President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

defended African Americans' newly won freedom and civil rights in the South by passing laws and using federal force to suppress the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, which had committed violence against blacks for years to suppress voting and discourage education. After Federal troops left in 1877 at the end of the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, many paramilitary groups worked to suppress black voting by violence. From 1890 to 1908 Southern states disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

most blacks and many poor whites through constitutional amendments and statutes that created barriers to voter registration and voting. Such devices as poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

and subjective literacy tests

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered t ...

sharply reduced the number of blacks in voting rolls. By the late nineteenth century, Southern white Democrats defeated some biracial Populist-Republican coalitions and regained power in the state legislatures of the former Confederacy; they passed laws establishing racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

. In the border states and North, blacks continued to exercise the vote; the well-established Maryland African-American community defeated attempts there to disfranchise them.

Washington worked and socialized with many national white politicians and industry leaders. He developed the ability to persuade wealthy whites, many of them self-made men, to donate money to black causes by appealing to their values. He argued that the surest way for blacks to gain equal social rights was to demonstrate "industry, thrift, intelligence and property". He believed these were key to improved conditions for African Americans in the United States. Because African Americans had recently been emancipated and most lived in a hostile environment, Washington believed they could not expect too much at once. He said, "I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has had to overcome while trying to succeed."

Along with Du Bois, Washington partly organized the "Negro exhibition" at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where photos of Hampton Institute's black students were displayed. These were taken by his friend Frances Benjamin Johnston

Frances Benjamin Johnston (January 15, 1864 – May 16, 1952) was an early American photographer and photojournalist whose career lasted for almost half a century. She is most known for her portraits, images of southern architecture, and various ...

. The exhibition demonstrated African Americans' positive contributions to United States' society.

Washington privately contributed substantial funds for legal challenges to segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

and disfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

, such as the case of '' Giles v. Harris'', which was heard before the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in 1903. Even when such challenges were won at the Supreme Court, southern states quickly responded with new laws to accomplish the same ends, for instance, adding "grandfather clauses

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

" that covered whites and not blacks in order to prevent blacks from voting.

Wealthy friends and benefactors

State and local governments historically underfunded black schools, although they were ostensibly providing "separate but equal" segregated facilities. White philanthropists strongly supported education financially. Washington encouraged them and directed millions of their money to projects all across the South that Washington thought best reflected his self-help philosophy. Washington associated with the richest and most powerful businessmen and politicians of the era. He was seen as a spokesperson for African Americans and became a conduit for funding educational programs.

His contacts included such diverse and well known entrepreneurs and philanthropists as

State and local governments historically underfunded black schools, although they were ostensibly providing "separate but equal" segregated facilities. White philanthropists strongly supported education financially. Washington encouraged them and directed millions of their money to projects all across the South that Washington thought best reflected his self-help philosophy. Washington associated with the richest and most powerful businessmen and politicians of the era. He was seen as a spokesperson for African Americans and became a conduit for funding educational programs.

His contacts included such diverse and well known entrepreneurs and philanthropists as Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

, William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

, Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was an American industrialist and financier. He made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil. He also played a major role in numerous corporations a ...

, George Eastman

George Eastman (July 12, 1854March 14, 1932) was an American entrepreneur who founded the Kodak, Eastman Kodak Company and helped to bring the photographic use of roll film into the mainstream. He was a major philanthropist, establishing the ...

, Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions in ...

, Robert Curtis Ogden

Robert Curtis Ogden (June 20, 1836 – August 6, 1913) was a businessman who promoted education in the Southern United States.

Biography

Ogden was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 20, 1836. He began work in a dry-goods store at 14 years ...

, Collis Potter Huntington

Collis Potter Huntington (October 22, 1821 – August 13, 1900) was an American industrialist and railway magnate. He was one of the Big Four of western railroading (along with Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker) who invested i ...

and William Henry Baldwin Jr.

William Henry Baldwin Jr. (February 5, 1863 – January 3, 1905) was an American railroad executive and philanthropist. He was president of the Long Island Rail Road. and was instrumental in establishing African American industrial education by s ...

The latter donated large sums of money to agencies such as the Jeanes and Slater Funds. As a result, countless small rural schools were established through Washington's efforts, under programs that continued many years after his death. Along with rich white men, the black communities helped their communities directly by donating time, money and labor to schools to match the funds required.

Henry Huttleston Rogers

A representative case of an exceptional relationship was Washington's friendship with millionaire industrialist and financier

A representative case of an exceptional relationship was Washington's friendship with millionaire industrialist and financier Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was an American industrialist and financier. He made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil. He also played a major role in numerous corporations a ...

(1840–1909). Henry Rogers was a self-made man

"Self-made man" is a classic phrase coined on February 2, 1842 by Henry Clay in the United States Senate, to describe individuals whose success lay within the individuals themselves, not with outside conditions. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Foun ...

, who had risen from a modest working-class family to become a principal officer of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

, and one of the richest men in the United States. Around 1894, Rogers heard Washington speak at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

. The next day, he contacted Washington and requested a meeting, during which Washington later recounted that he was told that Rogers "was surprised that no one had 'passed the hat' after the speech". The meeting began a close relationship that extended over a period of 15 years. Although Washington and the very private Rogers were seen as friends, the true depth and scope of their relationship was not publicly revealed until after Rogers's sudden death of a stroke in May 1909. Washington was a frequent guest at Rogers's New York office, his Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Fairhaven (Massachusett: ) is a town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the South Coast of Massachusetts where the Acushnet River flows into Buzzards Bay, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean. The town shares a harbor wit ...

summer home, and aboard his steam yacht ''Kanawha''.

A few weeks later, Washington went on a previously planned speaking tour along the newly completed Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads.

History

...

, a $40-million enterprise that had been built almost entirely from Rogers's personal fortune. As Washington rode in the late financier's private railroad car

A private railroad car, private railway coach, private car, or private varnish is a railroad passenger car either originally built or later converted for service as a business car for private individuals. A private car could be added to the make- ...

, ''Dixie'', he stopped and made speeches at many locations. His companions later recounted that he had been warmly welcomed by both black and white citizens at each stop.

Washington revealed that Rogers had been quietly funding operations of 65 small country schools for African Americans, and had given substantial sums of money to support Tuskegee and Hampton institutes. He also noted that Rogers had encouraged programs with matching funds

Matching funds are funds that are set to be paid in proportion to funds available from other sources. Matching fund payments usually arise in situations of charity or public good. The terms cost sharing, in-kind, and matching can be used interc ...

requirements so the recipients had a stake in the outcome.

Anna T. Jeanes

In 1907Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

Anna T. Jeanes

Anna T. Jeanes (7 April 1822 – 24 September 1907) was an American Quaker philanthropist. She was born in Philadelphia, the city where she gave Spring Garden Institute, a technical school, $5,000,000; $100,000 to the Hicksite Friends; $200,0 ...

(1822–1907) donated one million dollars to Washington for elementary schools for black children in the South. Her contributions and those of Henry Rogers and others funded schools in many poor communities.

Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions in ...

(1862–1932) was a Jewish American self-made wealthy man with whom Washington found common ground. By 1908, Rosenwald, son of an immigrant clothier, had become part-owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company

Sears, Roebuck and Co. ( ), commonly known as Sears, is an American chain of department stores founded in 1892 by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck and reincorporated in 1906 by Richard Sears and Julius Rosenwald, with what began a ...

in Chicago. Rosenwald was a philanthropist who was deeply concerned about the poor state of African-American education, especially in the segregated Southern states, where their schools were underfunded.

In 1912 l, Rosenwald was asked to serve on the Board of Directors of Tuskegee Institute, a position he held for the remainder of his life. Rosenwald endowed Tuskegee so that Washington could spend less time fundraising and more managing the school. Later in 1912, Rosenwald provided funds to Tuskegee for a pilot program to build six new small schools in rural Alabama. They were designed, constructed and opened in 1913 and 1914, and overseen by Tuskegee architects and staff; the model proved successful.

After Washington died in 1915, Rosenwald established the Rosenwald Fund in 1917, primarily to serve African-American students in rural areas throughout the South. The school building program was one of its largest programs. Using the architectural model plans developed by professors at Tuskegee Institute, the Rosenwald Fund spent over $4 million to help build 4,977 schools, 217 teachers' homes, and 163 shop buildings in 883 counties in 15 states, from Maryland to Texas. The Rosenwald Fund made matching grants

Matching funds are funds that are set to be paid in proportion to funds available from other sources. Matching fund payments usually arise in situations of charity or public good. The terms cost sharing, in-kind, and matching can be used interc ...

, requiring community support, cooperation from the white school boards, and local fundraising. Black communities raised more than $4.7 million to aid the construction and sometimes donated land and labor; essentially they taxed themselves twice to do so. These schools became informally known as Rosenwald Schools

The Rosenwald School project built more than 5,000 schools, shops, and teacher homes in the Education in the United States, United States primarily for the education of African-American children in the Southern United States, South during the ear ...

. But the philanthropist did not want them to be named for him, as they belonged to their communities. By his death in 1932, these newer facilities could accommodate one-third of all African-American children in Southern U.S. schools.

''Up from Slavery'' to the White House

Washington's long-term adviser,

Washington's long-term adviser, Timothy Thomas Fortune

Timothy Thomas Fortune (October 3, 1856June 2, 1928) was an orator, civil rights leader, journalist, writer, editor and publisher. He was the highly influential editor of the nation's leading black newspaper ''The New York Age'' and was the leadin ...

(1856–1928), was a respected African-American economist and editor of ''The New York Age

''The New York Age'' was a weekly newspaper established in 1887. It was widely considered one of the most prominent African-American newspapers of its time.

'', the most widely read newspaper in the black community within the United States. He was the ghost-writer and editor of Washington's first autobiography, ''The Story of My Life and Work''. Washington published five books during his lifetime with the aid of ghost-writers Timothy Fortune, Max Bennett Thrasher and Robert E. Park

Robert Ezra Park (February 14, 1864 – February 7, 1944) was an American urban sociologist who is considered to be one of the most influential figures in early U.S. sociology. Park was a pioneer in the field of sociology, changing it from a pas ...

.

They included compilations of speeches and essays:

* ''The Story of My Life and Work'' (1900)

* '' Up from Slavery'' (1901)

* ''The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery '' (2 vols., 1909)

* ''My Larger Education'' (1911)

* ''The Man Farthest Down'' (1912)

In an effort to inspire the "commercial, agricultural, educational, and industrial advancement" of African Americans, Washington founded the National Negro Business League

The National Negro Business League (NNBL) was an American organization founded in Boston in 1900 by Booker T. Washington to promote the interests of African-American businesses. The mission and main goal of the National Negro Business League was ...

(NNBL) in 1900.

When Washington's second autobiography, '' Up from Slavery'', was published in 1901, it became a bestseller—remaining the best-selling autobiography of an African American for over sixty years—and had a major effect on the African-American community and its friends and allies.

Dinner at the White House

In October 1901, PresidentTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

invited Washington to dine with him and his family at the White House.Although Republican presidents had met privately with black leaders, this was the first highly publicized social occasion when an African American was invited there on equal terms by the president. Democratic Party politicians from the South, including future governor of Mississippi James K. Vardaman

James Kimble Vardaman (July 26, 1861 – June 25, 1930) was an American politician from the U.S. state of Mississippi and was the Governor of Mississippi from 1904 to 1908. A Democrat, Vardaman was elected in 1912 to the United States Senate in ...

and Senator Benjamin Tillman

Benjamin Ryan Tillman (August 11, 1847 – July 3, 1918) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served as governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A whit ...

of South Carolina, indulged in racist personal attacks when they learned of the invitation. Both used the derogatory term for African Americans in their statements.

Vardaman described the White House as "so saturated with the odor of the nigger that the rats have taken refuge in the stable," and declared, "I am just as much opposed to Booker T. Washington as a voter as I am to the cocoanut-headed, chocolate-colored typical little coon who blacks my shoes every morning. Neither is fit to perform the supreme function of citizenship." Tillman said, "The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they will learn their place again."

Ladislaus Hengelmüller von Hengervár

Freiherr Ladislaus Hengelmüller von Hengervár ( hu, hengervári báró Hengelmüller László) (2 May 1845 – 22 April 1917), was an Austro-Hungarian diplomat of Hungarian origin who was a long-term Ambassador at Washington D.C., throughout m ...

, the Austro-Hungarian