Bombing of Lübeck in World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During

During

A. C. Grayling in his book, ''Among the Dead Cities'', makes the point that as the

A. C. Grayling in his book, ''Among the Dead Cities'', makes the point that as the

Under wartime and postwar conditions it took until 1948 to remove most of the construction waste and demolition rubble.

The remaining and the rebuilt parts of the old town are now part of the

Under wartime and postwar conditions it took until 1948 to remove most of the construction waste and demolition rubble.

The remaining and the rebuilt parts of the old town are now part of the

U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II: Combat Chronology May 1945

. Retrieved 8 September 2008

Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary: Bomber Command Campaign Diary

During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the city of Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

was the first German city to be attacked in substantial numbers by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. The attack on the night of 28 March 1942 created a firestorm

A firestorm is a conflagration which attains such intensity that it creates and sustains its own wind system. It is most commonly a natural phenomenon, created during some of the largest bushfires and wildfires. Although the term has been used ...

that caused severe damage to the historic centre, with bombs destroying three of the main churches and large parts of the built-up area. It led to the retaliatory "Baedeker" raids on historic British cities.

Although a port, and home to several shipyards, including the Lübecker Flender-Werke

Flender Werke was a German shipbuilding company, located in Lübeck. It was founded in 1917 as a branch of Brückenbau Flender AG of Benrath on the Rhine. In 1926 it was made a fully independent business and renamed Lübecker Flenderwerke AG. It ...

, Lübeck was also a cultural centre and only lightly defended. The bombing followed the Area Bombing Directive

The Area Bombing Directive was a directive from the wartime British Government's Air Ministry to the Royal Air Force, which ordered RAF Bomber Command to destroy Germany's industrial workforce and the morale of the German population, through bom ...

issued to the RAF on 14 February 1942 which authorised the targeting of civilian areas.

Main raid

Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

, a Hanseatic

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=German language, Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Norther ...

city and cultural centre on the shores of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, was easy to find under the light of the full moon on the night of Saturday 28 March 1942 and the early hours of 29 March (Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Holy ...

). Because of the hoar frost

Frost is a thin layer of ice on a solid surface, which forms from water vapor in an above-freezing atmosphere coming in contact with a solid surface whose temperature is below freezing, and resulting in a phase transition, phase change from wa ...

there was clear visibility and the waters of the Trave

The Trave () is a river in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is approximately long, running from its source near the village of Gießelrade in Ostholstein to Travemünde, where it flows into the Baltic Sea. It passes through Bad Segeberg, Bad Old ...

, the Elbe-Lübeck Canal, Wakenitz

The Wakenitz is a river in southeastern Schleswig-Holstein and at the border to Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

The Wakenitz's source is the Ratzeburger See in Ratzeburg. It is about long and drains into the Trave in Lübeck. The majority of its eas ...

and the Bay of Lübeck

The Bay of Lübeck (, ) is a basin in the southwestern Baltic Sea, off the shores of German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Schleswig-Holstein. It forms the southwestern part of the Bay of Mecklenburg.

The main port is Travemünde, a bor ...

were reflecting the moonlight.

234 Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

and Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

bombers dropped about 400 tons of bombs including 25,000 incendiary device

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, th ...

s and a number of 1.8 tonne landmines. RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

lost twelve aircraft in the attack.

There were few defences, so some crews attacked as low as 600 metres (2,000 feet) although the average bombing height was just over 3000 metres (10,000 feet). The attack took place in three waves, the first, which arrived over Lübeck at 23:18, consisting of experienced crews in aircraft fitted with Gee electronic navigation systems (Lübeck was beyond the range of Gee but it helped with preliminary navigation). The raid finished at 02:58 on Sunday morning. 191 crews claimed successful attacks.

Blockbuster bomb

A blockbuster bomb or cookie was one of several of the largest conventional bombs used in World War II by the Royal Air Force (RAF). The term ''blockbuster'' was originally a name coined by the press and referred to a bomb which had enough explo ...

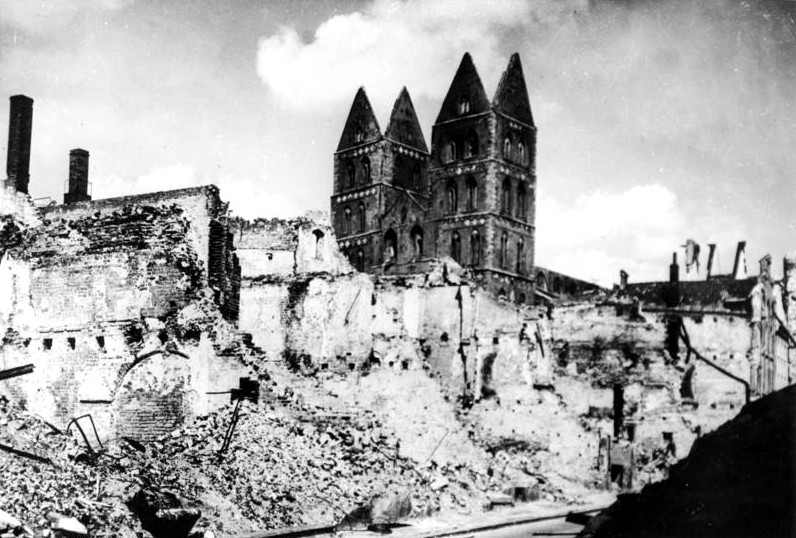

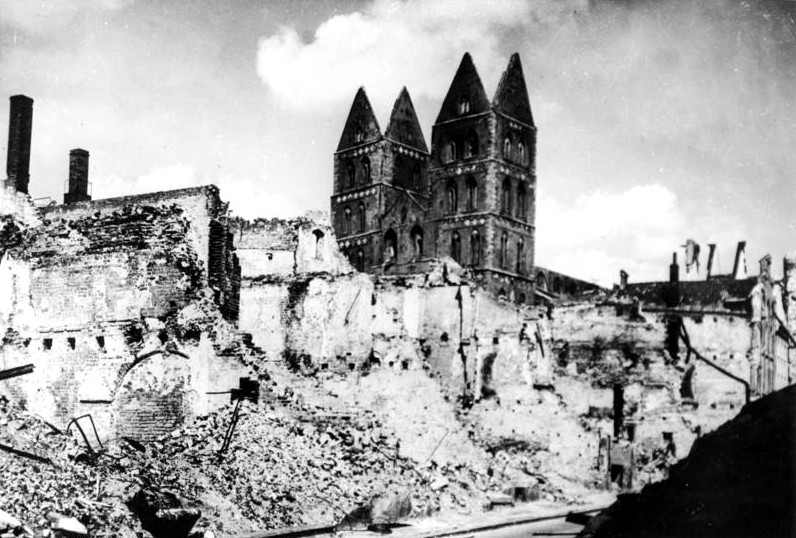

s in the first wave of the raid opened the brick and copper roofs of the buildings and the following incendiaries set them afire. 1,468 (or 7.1%) of the buildings in Lübeck were destroyed, 2,180 (10.6%) were seriously damaged and 9,103 (44.3%) were lightly damaged; these represented 62% of all buildings in Lübeck. The bombing of Lübeck struck a corridor about 300 metres (330 yards) wide from Lübeck Cathedral

Lübeck Cathedral (german: Dom zu Lübeck, or colloquially ''Lübecker Dom'') is a large brick-built Lutheran cathedral in Lübeck, Germany and part of the Lübeck World Heritage Site. It was started in 1173 by Henry the Lion as a cathedral for ...

to St. Peter's Church, the town hall and St. Mary's Church. There was another minor area of damage north of the Aegidienkirche. St. Lorenz, a residential suburb in the west of the Holstentor

The Holsten Gate (Low German and German: ''Holstentor'') is a city gate marking off the western boundary of the old center of the Hanseatic city of Lübeck. Built in 1464, the Brick Gothic construction is one of the relics of Lübeck's medieval ci ...

, was severely damaged. The German police reported 301 people dead, three people missing, and 783 injured. More than 15,000 people lost their homes.

Arthur Harris, Air Officer Commanding Bomber Command, described Lübeck as "built more like a fire-lighter than a human habitation". He wrote of the raid that " übeckwent up in flames" because "it was a city of moderate size of some importance as a port, and with some submarine building yards of moderate size not far from it. It was not a vital target, but it seemed to me better to destroy an industrial town of moderate importance than to fail to destroy a large industrial city". He goes on to describe that the loss of 5.5% of the attacking force was no more than to be expected on a clear moonlit night, but if that loss rate was to continue for any length of time RAF Bomber Command would not be able to "operate at the fullest intensity of which it were capable".

Aftermath and retaliation

A. C. Grayling in his book, ''Among the Dead Cities'', makes the point that as the

A. C. Grayling in his book, ''Among the Dead Cities'', makes the point that as the Area Bombing Directive

The Area Bombing Directive was a directive from the wartime British Government's Air Ministry to the Royal Air Force, which ordered RAF Bomber Command to destroy Germany's industrial workforce and the morale of the German population, through bom ...

issued to the RAF on 14 February 1942 focused on undermining the "morale of the enemy civil population", Lübeck – with its many timbered medieval buildings – was chosen because the RAF "Air Staff were eager to experiment with a bombing technique using a high proportion of incendiaries" to help them carry out the directive. The RAF was well aware that the technique of using a high proportion of incendiaries during bombing raids was effective because cities such as Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its ...

had been subject to such attacks by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

during the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

.. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

wrote to the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to inform him that similar "Coventry-scale" attacks would be mounted throughout the summer. The Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

congratulated Churchill on the outcome, expressing his satisfaction at the "merciless bombing" and expressing the hope that such attacks would cause severe damage to German public morale – a key objective for Churchill. A series of follow-up attacks, taking much the same pattern, was mounted against Rostock

Rostock (), officially the Hanseatic and University City of Rostock (german: link=no, Hanse- und Universitätsstadt Rostock), is the largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and lies in the Mecklenburgian part of the state, c ...

between 24 and 27 April 1942.Boog, p. 566

The German authorities mounted a prompt relief operation for the city's dispossessed. 25,000 people had been left homeless by the raid. The local branch of the National Socialist People's Welfare

The National Socialist People's Welfare (german: Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, NSV) was a social welfare organization during the Third Reich. The NSV was originally established in 1931 as a small Nazi Party-affiliated charity active loca ...

(NSV) organisation opened food stores and distributed 1.8 million oranges, 10 tonnes of apples, 40,000 loaves of bread, 16,000 eggs, 5,000 pounds of butter, 3,500 cans of food, 2,800 boxes of smoked herring and 50 barrels of Bismarck herring

Bismarck most often refers to:

* Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898), Prussian statesman and first Chancellor of Germany

* Bismarck, North Dakota, the capital of North Dakota, U.S.

* German battleship ''Bismarck'', a 1939 German World War II battlesh ...

. However, substantial amounts of luxury goods such as champagne, spirits, chocolates, clothing and shoes were pilfered by NSV officials. A number of them were arrested and in August 1942 three were sentenced to death for embezzlement with a further eleven jailed. The incident harmed the NSV's image, which had been positive up to that point.

The Nazi leadership was alarmed at the possible impact of the raid on civilian morale. In the opinion of Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, the Propaganda Minister, the raid fulfilled the RAF's directive, as he wrote in his diary: "The damage is really enormous, I have been shown a newsreel of the destruction. It is horrible. One can well imagine how such a bombardment affects the population." He commented: "Thank God, it is a North German population, which on the whole is much tougher than the Germans in the south or south-east. We can't get away from the fact that the English air-raids have increased in scope and importance; if they can be continued on these lines, they might conceivably have a demoralising effect on the population." Despite Goebbels' fears, civilian morale in Lübeck held up and the effect of the bombing on the city's economic life was soon overcome. To help offset the damage the raid had on German morale, the German hierarchy launched a well publicized raid on Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

on 23 April 1942, which was the first of the "Baedeker raids".

Red Cross port

In 1944 Eric Warburg, liaison officer between US Army Air Forces and RAF, andSwiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internation ...

diplomat Carl Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Burckhardt (September 10, 1891 – March 3, 1974) was a Swiss diplomat and historian. His career alternated between periods of academic historical research and diplomatic postings; the most prominent of the latter were League of Na ...

, as president of the International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

, declared the Lübeck port a ''Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

port'' to supply (under the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

) allied prisoners of war in German custody with ships under Swedish flag from Gothenburg

Gothenburg (; abbreviated Gbg; sv, Göteborg ) is the second-largest city in Sweden, fifth-largest in the Nordic countries, and capital of the Västra Götaland County. It is situated by the Kattegat, on the west coast of Sweden, and has ...

, which protected the city from further Allied air strikes. The mail and the food was brought to the POW camps

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

all over Germany by truck under supervision of the Swedish Red Cross and its vice president Folke Bernadotte

Folke Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg (2 January 1895 – 17 September 1948) was a Swedish nobleman and diplomat. In World War II he negotiated the release of about 31,000 prisoners from German concentration camps, including 450 Danish Jews fr ...

, who was in charge of the White Buses

White Buses was a Swedish humanitarian operation with the objective of freeing Scandinavians in German concentration camps in Nazi Germany during the final stages of World War II. Although the White Buses operation was envisioned to rescue Scan ...

too. (Bernadotte met Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

in Lübeck in spring 1945, when Himmler made his offer of surrender to the allies.)

Lübeck martyrs

A group of three Catholic clergymen, Johannes Prassek, Eduard Müller andHermann Lange

Hermann Lange (16 April 1912 – 10 November 1943) was a Roman Catholic priest and martyr of the Nazi period in Germany. He was guillotined in a Hamburg prison by the Nazi authorities in November 1943, along with the three other Lübeck marty ...

, and an Evangelical Lutheran pastor, Karl Friedrich Stellbrink

Karl Friedrich Stellbrink (28 October 1894 – 10 November 1943) was a German Lutheranism, Lutheran pastor, and one of the Lübeck martyrs, guillotined for opposing the Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler.

Biography

Born in Münster, Germany in 1894, son ...

, were arrested following the raid, tried by the People's Court in 1943 and sentenced to death by decapitation

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

; all were beheaded on 10 November 1943, in the Hamburg prison at ''Holstenglacis''. Stellbrink had explained the raid next morning in his Palm Sunday sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

as a "trial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal was an ancient judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused was determined by subjecting them to a painful, or at least an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience.

In medieval Europe, like trial by combat, tri ...

", which the Nazi authorities interpreted to be an attack on their system of government and as such undermined morale and aided the enemy.

Film

The bombing of the city served as the climax of the 1944 German film ''The Degenhardts

''The Degenhardts'' (german: Die Degenhardts) is a 1944 German drama film directed by Werner Klingler and starring Heinrich George, Ernst Schröder and Gunnar Möller. Karl Degenhardt, the patriarch of a family in Lübeck, leads his wife and five ...

'' directed by Werner Klingler

Karl Adolf Kurt Werner Klingler (23 October 1903 – 23 June 1972) was a German film director and actor. He directed 29 films between 1936 and 1968. He was born in Stuttgart and died in Berlin, Germany.

Early life

Klingler acquired his firs ...

. The film, featuring the home front

Home front is an English language term with analogues in other languages. It is commonly used to describe the full participation of the British public in World War I who suffered Zeppelin#During World War I, Zeppelin raids and endured Rationin ...

activities of a family in Lübeck, attempted to use the raid as moral justification for continued resistance against the Allies.

Reconstruction and memorial

Under wartime and postwar conditions it took until 1948 to remove most of the construction waste and demolition rubble.

The remaining and the rebuilt parts of the old town are now part of the

Under wartime and postwar conditions it took until 1948 to remove most of the construction waste and demolition rubble.

The remaining and the rebuilt parts of the old town are now part of the World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

. The bells that fell from the burning tower of St. Mary's church in a partly melted state have been left in the south tower as a memorial to the event. (See above) Since the reconstruction of St. Mary had priority, the reconstruction of the cathedral was not finished before 1982, the reconstruction of St. Peter not before 1986.

Another memorial to the people who were killed or displaced by the bombing is found in the Lübeck Ehrenfriedhof (cemetery) where there is a cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

and memorials to both wars. The memorial of the bombing of Lübeck is a statue by the sculptor Joseph Krautwald, who was commissioned in the 1960s to produce a work that reflected the experience of the victims. The statue, named ''Die Mutter'' (the mother), was carved from local coquina

Coquina () is a sedimentary rock that is composed either wholly or almost entirely of the transported, abraded, and mechanically sorted fragments of the shells of mollusks, trilobites, brachiopods, or other invertebrates. The term ''coquina'' ...

and shows a mourning woman with two little children. It is placed in the center of the circle surrounded by the tombstones of those who died that night.

Chronology of air raids on Lübeck

* 28/29 March 1942: first and main RAF raid, followed by some minor raids in connection with the bombing of other north German cities as targets. * 16 July 1942: 21 Stirlings in an RAF raid. Only 8 aircraft reported bombing the main target; 2 Stirlings were lost. * 24/25 July 1943: first raid of the Battle of Hamburg, 13 RAFMosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

s carried out diversionary and nuisance raids to Bremen, Kiel, Lübeck and Duisburg.

* 25 August 1944 (Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Force ...

Mission 570): 81 B-24s bombed aircraft component plants, a rifle factory and steel fabrication plant in Lübeck – local sources reported 110 dead including 39 ''Zwangsarbeiter'' (forced (slave) laborers).

* 15/16 September 1944: diversionary raid by 9 RAF Mosquitoes. The main raid was on Kiel with other cities hit by diversionary raids.

* 2/3 April 1945: training raid by one RAF aircraft.

* 3 May 1945 in a tactical operation the USAAF Ninth Air Force

The Ninth Air Force (Air Forces Central) is a Numbered Air Force of the United States Air Force headquartered at Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina. It is the Air Force Service Component of United States Central Command (USCENTCOM), a joint De ...

flew armed reconnaissance around Kiel and Lübeck, and A-26 Invader

The Douglas A-26 Invader (designated B-26 between 1948 and 1965) is an American twin-engined light bomber and ground attack aircraft. Built by Douglas Aircraft Company during World War II, the Invader also saw service during several major Col ...

s of the XXIX Tactical Air Command (Provisional)

The XXIX Tactical Air Command (Provisional) was a provisional United States Army Air Forces unit, primarily formed from units of IX Fighter Command. Its last assignment was with Ninth Air Force at Weimar, Germany, where it was inactivated on 25 O ...

hit shipping in the Kiel-Lübeck area.. Retrieved 8 September 2008

See also

*The tragedy of the sinking of the SS ''Cap Arcona'' on 3 May 1945 happened on theBay of Lübeck

The Bay of Lübeck (, ) is a basin in the southwestern Baltic Sea, off the shores of German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Schleswig-Holstein. It forms the southwestern part of the Bay of Mecklenburg.

The main port is Travemünde, a bor ...

close to the port of Neustadt in Holstein

Neustadt in Holstein (; Holsatian: ''Niestadt in Holsteen'') is a town in the district of Ostholstein, in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, on the Bay of Lübeck 30 km northeast of Lübeck, and 50 km southeast of Kiel.

History

In World War I ...

and not in Lübeck itself.

*Bath Blitz

The term Bath Blitz refers to the air raids by the German ''Luftwaffe'' on the British city of Bath, Somerset, during World War II.

The city was bombed in April 1942 as part of the so-called "Baedeker raids", in which targets were chosen for th ...

References

*Graßmann, Antjekathrin (1989). ''Lübeckische Geschichte''. (''Lübeck's history''). 934 p., Lübeck. *Grayling, A. C. (2006). ''Among the dead cities''; Bloomsbury (2006); . Pages 50–51 *Harris, Arthur (1947). ''Bomber Offensive'', Pen & Swords, (Paperback 2005), ; page 105Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary: Bomber Command Campaign Diary

Footnotes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bombing of Lubeck in World War IiLübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

History of Lübeck

1942 in Germany

Conflicts in 1942

Germany–United Kingdom military relations