Bloodletting on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) is the withdrawal of

Passages from the Ebers Papyrus may indicate that bloodletting by scarification was an accepted practice in Ancient Egypt.

Egyptian burials have been reported to contain bloodletting instruments.

According to some accounts, the Egyptians based the idea on their observations of the

Passages from the Ebers Papyrus may indicate that bloodletting by scarification was an accepted practice in Ancient Egypt.

Egyptian burials have been reported to contain bloodletting instruments.

According to some accounts, the Egyptians based the idea on their observations of the

probability sample files (PSF)

list. The PSF is a subset of eHRAF data that includes only one culture from each of 60 macro-culture areas around the world. The prevalence of bloodletting in PSF controls for pseudo replication linked to common ancestry, suggesting that bloodletting has independently emerged many times. Bloodletting is varied in its practices cross-culturally, for example, in native Alaskan culture bloodletting was practiced for different indications, using different tools, on different body areas, by different people, and it was explained by different medical theories. According to Helena Miton et al.'s analysis of the eHRAF database and other sources, there are several cross-cultural patterns in bloodletting. * Bloodletting is not self-administered. Out of 14 cultures in which the bloodletting practitioner was mentioned, the practitioner was always a third party. 13/14 of the cultures had practitioners with roles related to medicine, while one culture had a practitioner whose role was not related to medicine. * Idea of bloodletting removing 'bad blood' that needs to be taken out was common, and was explicitly mentioned in 10/14 cultures studied with detailed descriptions of bloodletting. * Bloodletting is not thought to be effective against illness caused supernaturally by humans (e.g. witchcraft). This is surprising, because in most cultures witchcraft and sorcery can be blamed for ailments. But out of 14 cultures with detailed bloodletting descriptions, there was no evidence of bloodletting being used to cure witchcraft-related ailments, while bloodletting was recorded as a cure for ailments of other origins. The Azande culture has been recorded to believe that bloodletting does not work to cure human-related witchcraft ailments. * Bloodletting is usually administered directly to the effected area, e.g. if the patient has a headache, a cut is made on the forehead. Out of 14 cultures with information on the localization of bloodletting, 11 at least sometimes removed blood from the affected area, while 3 specifically removed blood from a different area from the area in pain. Europe is the only continent with more instances of non-colocalized than colocalized bloodletting. In a transmission chain experiment done on people living in the US through

Bloodletting became a main technique of

Bloodletting became a main technique of

A number of different methods were employed. The most common was ''phlebotomy'', or ''venesection'' (often called "breathing a vein"), in which blood was drawn from one or more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm or neck. In ''arteriotomy'', an artery was punctured, although generally only in the temples. In ''scarification'' (not to be confused with

A number of different methods were employed. The most common was ''phlebotomy'', or ''venesection'' (often called "breathing a vein"), in which blood was drawn from one or more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm or neck. In ''arteriotomy'', an artery was punctured, although generally only in the temples. In ''scarification'' (not to be confused with

, p. 79, Spring, 2004, retrieved on 11 November 2012 One reason for the continued popularity of bloodletting (and purging) was that, while

One reason for the continued popularity of bloodletting (and purging) was that, while

, holistic-online.com.Ayurveda

, Cancer.org.

/ref>Treating Herpes Zoster (Shingles) with Bloodletting Therapy: Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine

Unani is based on a form of humorism, and so in that system, bloodletting is used to correct supposed humoral imbalance.

The History and Progression of Bloodletting

Huge collection of antique bloodletting instruments

"Breathing a Vein"

phisick.com 14 Nov 2011 {{Use dmy dates, date=January 2021 Blood Bleeding Medical tests Medical treatments Obsolete medical procedures Traditional medicine Pseudoscience Phlebotomy

blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leech

Leeches are segmented parasitic or predatory worms that comprise the subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the oligochaetes, which include the earthworm, and like them have soft, muscular segmented bodie ...

es, was based on an ancient system of medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

in which blood and other bodily fluids were regarded as "humours

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

" that had to remain in proper balance to maintain health. It is claimed to have been the most common medical practice performed by surgeons from antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

until the late 19th century, a span of over 2,000 years. In Europe, the practice continued to be relatively common until the end of the 19th century.B.) Anderson, Julie, Emm Barnes, and Enna Shackleton. "The Art of Medicine: Over 2,000 Years of Images and Imagination ardcover" The Art of Medicine: Over 2,000 Years of Images and Imagination: Julie Anderson, Emm Barnes, Emma Shackleton: : The Ilex Press Limited, 2013. The practice has now been abandoned by modern-style medicine for all except a few very specific medical condition

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medica ...

s. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the historical use of bloodletting was harmful to patients.

Today, the term ''phlebotomy

Phlebotomy is the process of making a puncture in a vein, usually in the arm, with a cannula for the purpose of drawing blood. The procedure itself is known as a venipuncture, which is also used for intravenous therapy. A person who performs a ph ...

'' refers to the drawing of blood for laboratory analysis or blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used whole blood, but mo ...

. ''Therapeutic phlebotomy'' refers to the drawing of a unit of blood in specific cases like hemochromatosis

Iron overload or hemochromatosis (also spelled ''haemochromatosis'' in British English) indicates increased total accumulation of iron in the body from any cause and resulting organ damage. The most important causes are hereditary haemochromatosi ...

, polycythemia vera

Polycythemia vera is an uncommon myeloproliferative neoplasm (a type of chronic leukemia) in which the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells. It may also result in the overproduction of white blood cells and platelets.

Most of the health ...

, porphyria cutanea tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common subtype of porphyria. The disease is named because it is a porphyria that often presents with skin manifestations later in life. The disorder results from low levels of the enzyme responsible for the fift ...

, etc., to reduce the number of red blood cells. The traditional medical practice of bloodletting is today considered to be a pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or falsifiability, unfa ...

.

In the ancient world

Passages from the Ebers Papyrus may indicate that bloodletting by scarification was an accepted practice in Ancient Egypt.

Egyptian burials have been reported to contain bloodletting instruments.

According to some accounts, the Egyptians based the idea on their observations of the

Passages from the Ebers Papyrus may indicate that bloodletting by scarification was an accepted practice in Ancient Egypt.

Egyptian burials have been reported to contain bloodletting instruments.

According to some accounts, the Egyptians based the idea on their observations of the hippopotamus

The hippopotamus ( ; : hippopotamuses or hippopotami; ''Hippopotamus amphibius''), also called the hippo, common hippopotamus, or river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of only two extan ...

, confusing its red secretions with blood and believing that it scratched itself to relieve distress.

In Greece, bloodletting was in use in the 5th century BC during the lifetime of Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of ...

, who mentions this practice but generally relied on dietary techniques. Erasistratus

Erasistratus (; grc-gre, Ἐρασίστρατος; c. 304 – c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where the ...

, however, theorized that many diseases were caused by plethoras, or overabundances, in the blood and advised that these plethoras be treated, initially, by exercise

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic ...

, sweating

Perspiration, also known as sweating, is the production of fluids secreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals.

Two types of sweat glands can be found in humans: eccrine glands and apocrine glands. The eccrine sweat glands are distr ...

, reduced food intake, and vomiting. His student Herophilus

Herophilos (; grc-gre, Ἡρόφιλος; 335–280 BC), sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician regarded as one of the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first sci ...

also opposed bloodletting. But a contemporary Greek physician, Archagathus, one of the first to practice in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, did believe in the value of bloodletting.

"Bleeding" a patient to health was modeled on the process of menstruation

Menstruation (also known as a period, among other colloquial terms) is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina. The menstrual cycle is characterized by the rise and fall of hor ...

. Hippocrates believed that menstruation functioned to "purge women of bad humours". During the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, the Greek physician Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

, who subscribed to the teachings of Hippocrates, advocated physician-initiated bloodletting.

The popularity of bloodletting in the classical Mediterranean world was reinforced by the ideas of Galen, after he discovered that not only vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated b ...

s but also arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pul ...

were filled with blood, not air as was commonly believed at the time. There were two key concepts in his system of bloodletting. The first was that blood was created and then used up; it did not circulate

''Circulate'' is the second solo album of Neil Sedaka after his 1959 debut solo album '' Rock with Sedaka''. ''Circulate'' was released in 1961 by RCA Victor and was produced by Al Nevins and Don Kirshner. Except for the title song "Circulate ...

, and so it could "stagnate" in the extremities. The second was that humoral

Humoral immunity is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by macromolecules - including secreted antibodies, complement proteins, and certain antimicrobial peptides - located in extracellular fluids. Humoral immunity is named so because it invo ...

balance was the basis of illness or health, the four humours being blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile, relating to the four Greek classical element

Classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had simil ...

s of air, water, earth, and fire respectively. Galen believed that blood was the dominant humour and the one in most need of control. In order to balance the humours, a physician would either remove "excess" blood (plethora) from the patient or give them an emetic

Vomiting (also known as emesis and throwing up) is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteri ...

to induce vomiting, or a diuretic

A diuretic () is any substance that promotes diuresis, the increased production of urine. This includes forced diuresis. A diuretic tablet is sometimes colloquially called a water tablet. There are several categories of diuretics. All diuretics in ...

to induce urination.

Galen created a complex system of how much blood should be removed based on the patient's age, constitution, the season, the weather and the place. "Do-it-yourself" bleeding instructions following these systems were developed. Symptoms of plethora were believed to include fever, apoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

, and headache. The blood to be let was of a specific nature determined by the disease: either arterial or venous

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated b ...

, and distant or close to the area of the body affected. He linked different blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

s with different organs

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a fu ...

, according to their supposed drainage. For example, the vein in the right hand would be let for liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

problems and the vein in the left hand for problems with the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

. The more severe the disease, the more blood would be let. Fevers required copious amounts of bloodletting.

Cross-cultural bloodletting

Therapeutic uses of bloodletting were reported in 60 distinct cultures/ethnic groups in the eHRAF database, present in all inhabited continents. Bloodletting is also reported in 15 of the 60 cultures in thprobability sample files (PSF)

list. The PSF is a subset of eHRAF data that includes only one culture from each of 60 macro-culture areas around the world. The prevalence of bloodletting in PSF controls for pseudo replication linked to common ancestry, suggesting that bloodletting has independently emerged many times. Bloodletting is varied in its practices cross-culturally, for example, in native Alaskan culture bloodletting was practiced for different indications, using different tools, on different body areas, by different people, and it was explained by different medical theories. According to Helena Miton et al.'s analysis of the eHRAF database and other sources, there are several cross-cultural patterns in bloodletting. * Bloodletting is not self-administered. Out of 14 cultures in which the bloodletting practitioner was mentioned, the practitioner was always a third party. 13/14 of the cultures had practitioners with roles related to medicine, while one culture had a practitioner whose role was not related to medicine. * Idea of bloodletting removing 'bad blood' that needs to be taken out was common, and was explicitly mentioned in 10/14 cultures studied with detailed descriptions of bloodletting. * Bloodletting is not thought to be effective against illness caused supernaturally by humans (e.g. witchcraft). This is surprising, because in most cultures witchcraft and sorcery can be blamed for ailments. But out of 14 cultures with detailed bloodletting descriptions, there was no evidence of bloodletting being used to cure witchcraft-related ailments, while bloodletting was recorded as a cure for ailments of other origins. The Azande culture has been recorded to believe that bloodletting does not work to cure human-related witchcraft ailments. * Bloodletting is usually administered directly to the effected area, e.g. if the patient has a headache, a cut is made on the forehead. Out of 14 cultures with information on the localization of bloodletting, 11 at least sometimes removed blood from the affected area, while 3 specifically removed blood from a different area from the area in pain. Europe is the only continent with more instances of non-colocalized than colocalized bloodletting. In a transmission chain experiment done on people living in the US through

Amazon Mechanical Turk

Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) is a crowdsourcing website for businesses to hire remotely located "crowdworkers" to perform discrete on-demand tasks that computers are currently unable to do. It is operated under Amazon Web Services, and is owned ...

, stories about bloodletting in a non-affected area were much more likely to transition into stories about bloodletting being administered near the area in pain than vice versa. This suggests that colocalized bloodletting could be a cultural attractor and is more likely to be culturally transmitted, even among people in the US who are likely more familiar with non-colocalized bloodletting.

Bloodletting as a concept is thought to be a cultural attractor, or an intrinsically attractive / culturally transmissible concept. This could explain bloodletting's independent cross-cultural emergence and common cross-cultural traits.

Middle Ages

TheTalmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cente ...

recommended a specific day of the week and days of the month for bloodletting in the Shabbat tractate, and similar rules, though less codified, can be found among Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

writings advising which saints' days

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context d ...

were favourable for bloodletting. During medieval times bleeding charts were common, showing specific bleeding sites on the body in alignment with the planets and zodiacs. Islamic medical authors also advised bloodletting, particularly for fevers. It was practised according to seasons and certain phases of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

in the lunar calendar

A lunar calendar is a calendar based on the monthly cycles of the Moon's phases (synodic months, lunations), in contrast to solar calendars, whose annual cycles are based only directly on the solar year. The most commonly used calendar, the Gre ...

. The practice was probably passed by the Greeks with the translation of ancient texts to Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

and is different than bloodletting by cupping mentioned in the traditions

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays or ...

of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

. When Muslim theories became known in the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

-speaking countries of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, bloodletting became more widespread. Together with cautery

Cauterization (or cauterisation, or cautery) is a medical practice or technique of burning a part of a body to remove or close off a part of it. It destroys some tissue in an attempt to mitigate bleeding and damage, remove an undesired growth, or ...

, it was central to Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

ic surgery; the key texts '' Kitab al-Qanun'' and especially ' both recommended it. It was also known in Ayurvedic

Ayurveda () is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. Ayurveda is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population rep ...

medicine, described in the ''Susruta Samhita''.

Use through the 19th century

heroic medicine

Heroic medicine, also referred to as heroic depletion theory, was a therapeutic method advocating for rigorous treatment of bloodletting, purging, and sweating to shock the body back to health after an illness caused by a humoral imbalance. Risi ...

, a traumatic and destructive collection of medical practices that emerged in the 18th century.

Even after the humoral system fell into disuse, the practice was continued by surgeons

In modern medicine, a surgeon is a medical professional who performs surgery. Although there are different traditions in different times and places, a modern surgeon usually is also a licensed physician or received the same medical training as ...

and barber-surgeons

The barber surgeon, one of the most common European medical practitioners of the Middle Ages, was generally charged with caring for soldiers during and after battle. In this era, surgery was seldom conducted by physicians, but instead by barbers ...

. Though the bloodletting was often ''recommended'' by physicians, it was carried out by barbers. This led to the distinction between physicians and surgeons. The red-and-white-striped pole of the barbershop, still in use today, is derived from this practice: the red symbolizes blood while the white symbolizes the bandages. Bloodletting was used to "treat" a wide range of diseases, becoming a standard treatment for almost every ailment, and was practiced prophylactically as well as therapeutically.

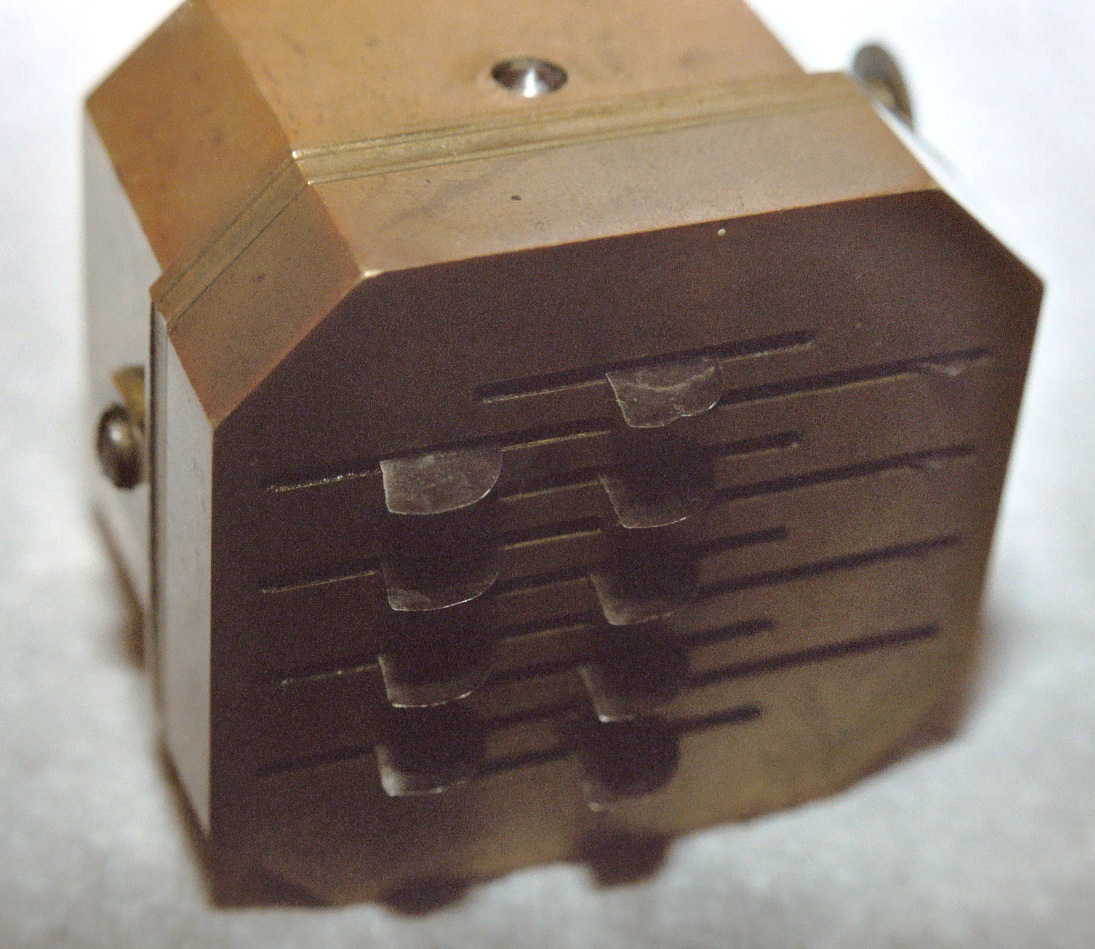

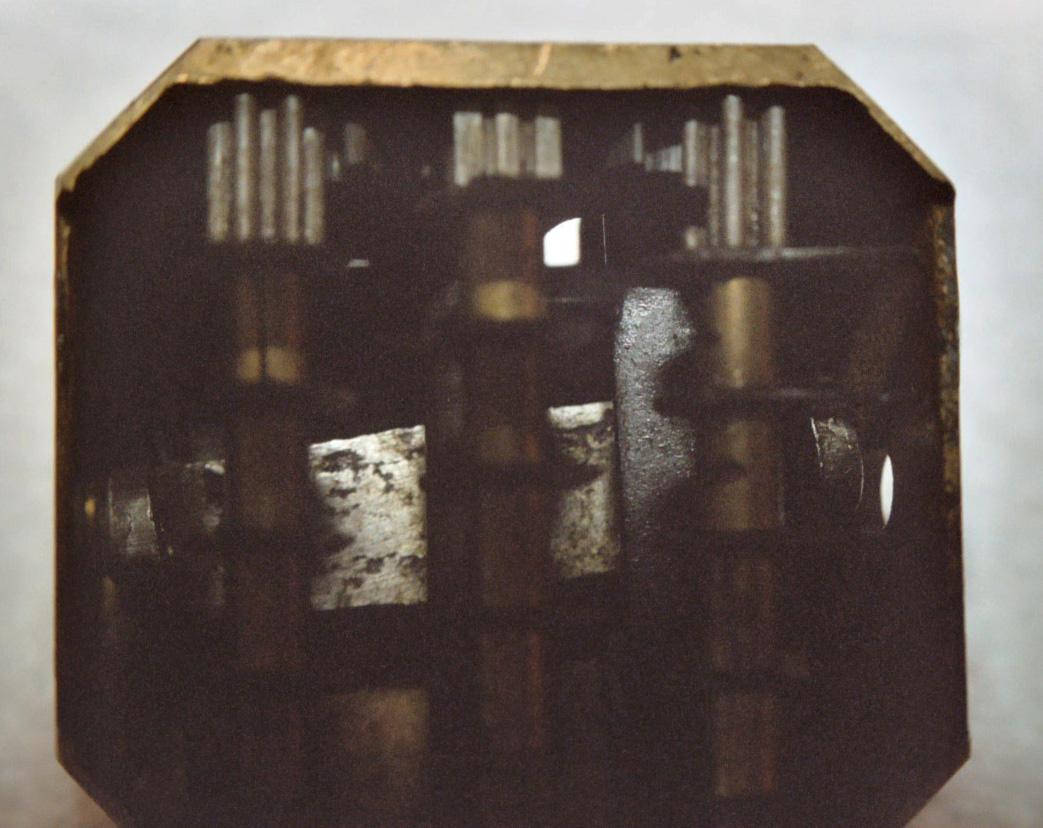

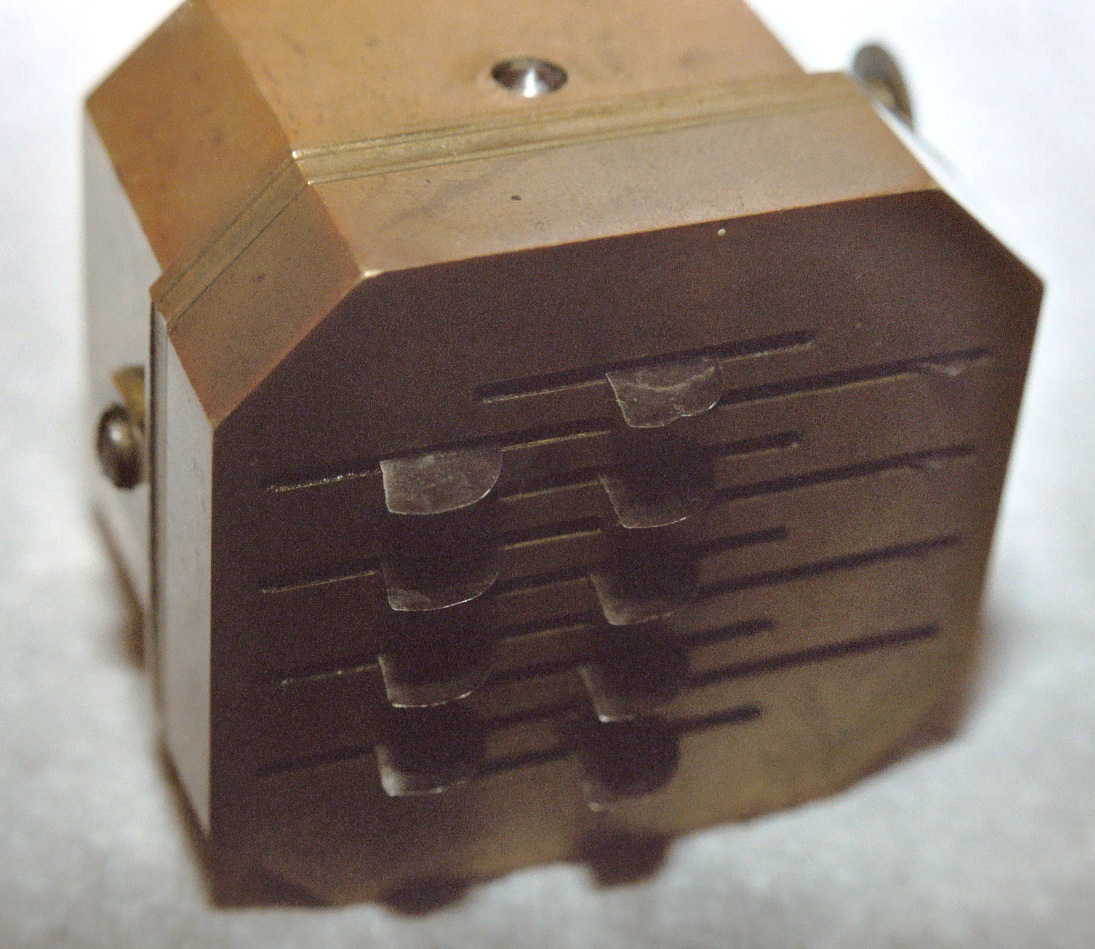

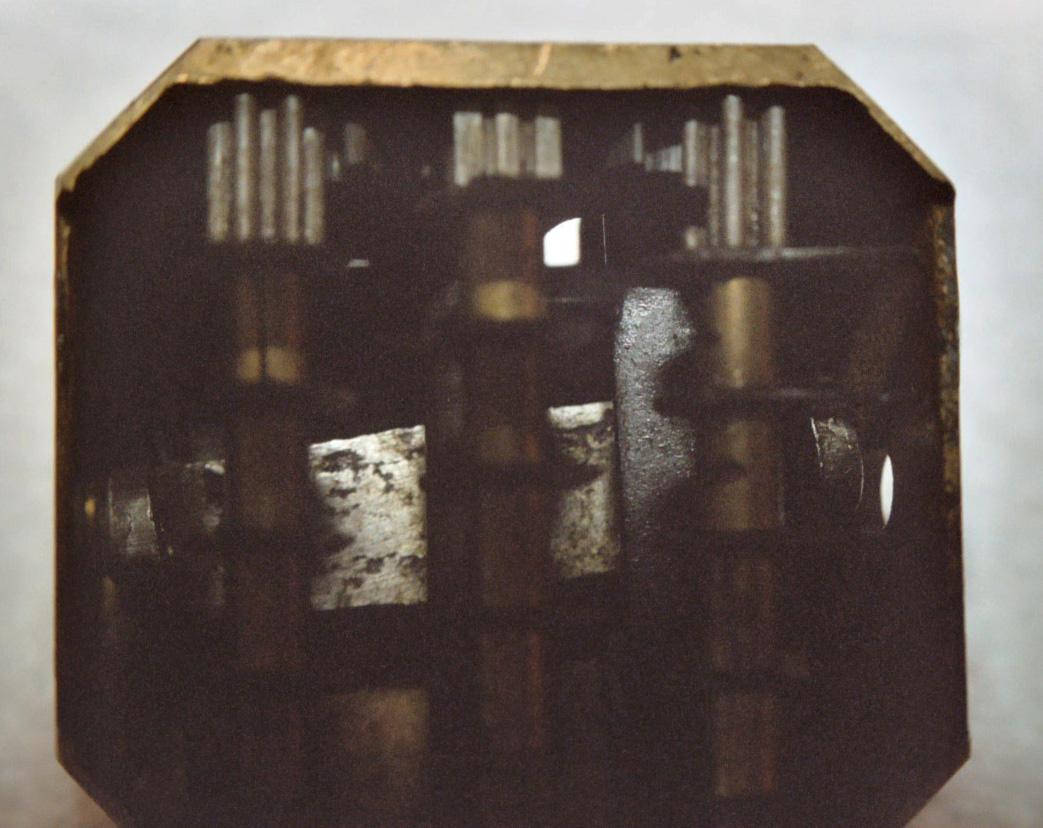

A number of different methods were employed. The most common was ''phlebotomy'', or ''venesection'' (often called "breathing a vein"), in which blood was drawn from one or more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm or neck. In ''arteriotomy'', an artery was punctured, although generally only in the temples. In ''scarification'' (not to be confused with

A number of different methods were employed. The most common was ''phlebotomy'', or ''venesection'' (often called "breathing a vein"), in which blood was drawn from one or more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm or neck. In ''arteriotomy'', an artery was punctured, although generally only in the temples. In ''scarification'' (not to be confused with scarification

Scarification involves scratching, etching, burning/branding, or superficially cutting designs, pictures, or words into the skin as a permanent body modification or body art. The body modification can take roughly 6–12 months to heal. In the p ...

, a method of body modification), the "superficial" vessels were attacked, often using a syringe, a spring-loaded lancet, or a glass cup that contained heated air, producing a vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

within (see fire cupping

Cupping therapy is a form of alternative medicine in which a local suction is created on the skin with the application of heated cups. Its practice mainly occurs in Asia but also in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America. Cupping has ...

). There was also a specific bloodletting tool called a ''scarificator'', used primarily in 19th century medicine. It has a spring-loaded mechanism with gears that snaps the blades out through slits in the front cover and back in, in a circular motion. The case is cast brass, and the mechanism and blades steel. One knife bar gear has slipped teeth, turning the blades in a different direction than those on the other bars. The last photo and the diagram show the depth adjustment bar at the back and sides.

Leech

Leeches are segmented parasitic or predatory worms that comprise the subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the oligochaetes, which include the earthworm, and like them have soft, muscular segmented bodie ...

es could also be used. The withdrawal of so much blood as to induce syncope (fainting) was considered beneficial, and many sessions would only end when the patient began to swoon.

William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and proper ...

disproved the basis of the practice in 1628, and the introduction of scientific medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practices ...

, ''la méthode numérique'', allowed Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis

Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis (14 April 178722 August 1872) was a French physician, clinician and pathology, pathologist known for his studies on tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and pneumonia, but Louis's greatest contribution to medicine was the de ...

to demonstrate that phlebotomy was entirely ineffective in the treatment of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

and various fevers in the 1830s. Nevertheless, in 1838, a lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

would still state that "blood-letting is a remedy which, when judiciously employed, it is hardly possible to estimate too highly", and Louis was dogged by the sanguinary Broussais, who could recommend leeches fifty at a time. Some physicians resisted Louis' work because they "were not prepared to discard therapies 'validated by both tradition and their own experience on account of somebody else's numbers'."

During this era, bloodletting was used to treat almost every disease. One British medical text recommended bloodletting for acne, asthma, cancer, cholera, coma, convulsions, diabetes, epilepsy, gangrene, gout, herpes, indigestion, insanity, jaundice, leprosy, ophthalmia, plague, pneumonia, scurvy, smallpox, stroke, tetanus, tuberculosis, and for some one hundred other diseases. Bloodletting was even used to treat most forms of hemorrhaging such as nosebleed, excessive menstruation, or hemorrhoidal bleeding. Before surgery or at the onset of childbirth, blood was removed to prevent inflammation. Before amputation, it was customary to remove a quantity of blood equal to the amount believed to circulate in the limb that was to be removed.Carter (2005) p. 6

There were also theories that bloodletting would cure "heartsickness" and "heartbreak". A French physician, Jacques Ferrand

Jacques Ferrand was a French physician born around 1575 in Agen, France. He is famous for his treatise on melancholia, ''Traicte de l'essence et guerison de l'amour ou de la melancholie erotique'' (1610), an early psychological work on melancholia. ...

wrote a book in 1623 on the uses of bloodletting to cure a broken heart. He recommended bloodletting to the point of heart failure (literal).Lydia Kang MD & Nate Pederson, ''Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything'' "Bleed Yourself to Bliss" (Workman Publishing Company; 2017)

Leeches became especially popular in the early 19th century. In the 1830s, the French imported about 40 million leeches a year for medical purposes, and in the next decade, England imported 6 million leeches a year from France alone. Through the early decades of the century, hundreds of millions of leeches were used by physicians throughout Europe.Carter (2005) p. 7

Bloodletting was also popular in the young United States of America, where Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, ...

(a signatory of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

) saw the state of the arteries as the key to disease, recommending levels of bloodletting that were high even for the time. George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

asked to be bled heavily after he developed a throat infection from weather exposure. Within a ten-hour period, a total of 124–126 ounces

The ounce () is any of several different units of mass, weight or volume and is derived almost unchanged from the , an Ancient Roman unit of measurement.

The avoirdupois ounce (exactly ) is avoirdupois pound; this is the United States customa ...

(3.75 liters) of blood was withdrawn prior to his death from a throat infection in 1799.The Permanente Journal Volume 8 No. 2: The asphyxiating and exsanguinating death of president george washington, p. 79, Spring, 2004, retrieved on 11 November 2012

One reason for the continued popularity of bloodletting (and purging) was that, while

One reason for the continued popularity of bloodletting (and purging) was that, while anatomical

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

knowledge, surgical and diagnostic skills increased tremendously in Europe from the 17th century, the key to curing disease remained elusive, and the underlying belief was that it was better to give any treatment than nothing at all. The psychological benefit of bloodletting to the patient (a placebo effect

A placebo ( ) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like Saline (medicine), saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

In general ...

) may sometimes have outweighed the physiological problems it caused. Bloodletting slowly lost favour during the 19th century, after French physician Dr. Pierre Louis conducted an experiment in which he studied the effect of bloodletting on pneumonia patients. A number of other ineffective or harmful treatments were available as placebos—mesmerism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, was a protoscientific theory developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century in relation to what he claimed to be an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all livi ...

, various processes involving the new technology of electricity, many potions, tonics, and elixirs. Yet, bloodletting persisted during the 19th century partly because it was readily available to people of any socioeconomic status.

Barbara Ehrenreich

Barbara Ehrenreich (, ; ; August 26, 1941 – September 1, 2022) was an American author and political activist. During the 1980s and early 1990s, she was a prominent figure in the Democratic Socialists of America. She was a widely read and awar ...

and Deirdre English

Deirdre English (born 1948) is the former editor of ''Mother Jones'' and author of numerous articles for national publications and television documentaries. She has taught at the State University of New York and currently teaches at the Graduate S ...

write that the popularity of bloodletting and heroic medicine in general was because of a need to justify medical billing. Traditional healing techniques had been mostly practiced by women within a non-commercial family or village setting. As male doctors suppressed these techniques, they found it difficult to quantify various "amounts" of healing to charge for, and difficult to convince patients to pay for it. Because bloodletting seemed active and dramatic, it helped convince patients the doctor had something tangible to sell.

Controversy and use into the 20th century

Bloodletting gradually declined in popularity over the course of the 19th century, becoming rather uncommon in most places, before its validity was thoroughly debated. In the medical community ofEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, bloodletting was abandoned in practice before it was challenged in theory, a contradiction highlighted by physician-physiologist John Hughes Bennett

John Hughes Bennett PRCPE FRSE (31 August 1812 – 25 September 1875) was an English physician, physiologist and pathologist. His main contribution to medicine has been the first description of leukemia as a blood disorder (1845). The first pe ...

. Authorities such as Austin Flint I

Austin Flint I (October 20, 1812 – March 13, 1886) was an American physician. He was a founder of Buffalo Medical College, precursor to University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, The State University of New York at Buffalo. He s ...

, Hiram Corson, and William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first Residency (medicine), residency program for spec ...

became prominent supporters of bloodletting in the 1880s and onwards, disputing Bennett's premise that bloodletting had fallen into disuse because it did not work. These advocates framed bloodletting as an orthodox medical practice, to be used in spite of its general unpopularity. Some physicians considered bloodletting useful for a more limited range of purposes, such as to "clear out" infected or weakened blood or its ability to "cause hæmorrhages to cease"—as evidenced in a call for a "fair trial for blood-letting as a remedy" in 1871.

Some researchers used statistical methods for evaluating treatment effectiveness to discourage bloodletting. But at the same time, publications by Philip Pye-Smith

Philip Henry Pye-Smith FRS FRCP (30 August 1839 – 23 May 1914) was an English physician, medical scientist and educator. His interest was physiology, specialising in skin diseases.

Life

Philip Pye-Smith was born in 1839 at Billiter Square, L ...

and others defended bloodletting on scientific grounds.

Bloodletting persisted into the 20th century and was recommended in the 1923 edition of the textbook ''The Principles and Practice of Medicine

''The Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine'' is a medical textbook by Sir William Osler. It was first published in 1892 by D. Appleton & Company, while Osler was professor of Medicine ...

''. The textbook was originally written by Sir William Osler and continued to be published in new editions under new authors following Osler's death in 1919.

Phlebotomy

Bloodletting is used today in the treatment of a few diseases, includinghemochromatosis

Iron overload or hemochromatosis (also spelled ''haemochromatosis'' in British English) indicates increased total accumulation of iron in the body from any cause and resulting organ damage. The most important causes are hereditary haemochromatosi ...

and polycythemia

Polycythemia (also known as polycythaemia) is a laboratory finding in which the hematocrit (the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood) and/or hemoglobin concentration are increased in the blood. Polycythemia is sometimes called erythr ...

. It is practiced by specifically trained practitioners in hospitals, using modern techniques, and is also known as a therapeutic phlebotomy

A therapy or medical treatment (often abbreviated tx, Tx, or Tx) is the attempted remediation of a health problem, usually following a medical diagnosis.

As a rule, each therapy has indications and contraindications. There are many different ...

.

In most cases, phlebotomy

Phlebotomy is the process of making a puncture in a vein, usually in the arm, with a cannula for the purpose of drawing blood. The procedure itself is known as a venipuncture, which is also used for intravenous therapy. A person who performs a ph ...

now refers to the removal of ''small'' quantities of blood for diagnostic purposes. However, in the case of hemochromatosis

Iron overload or hemochromatosis (also spelled ''haemochromatosis'' in British English) indicates increased total accumulation of iron in the body from any cause and resulting organ damage. The most important causes are hereditary haemochromatosi ...

, bloodletting (by venipuncture

In medicine, venipuncture or venepuncture is the process of obtaining intravenous access for the purpose of venous blood sampling (also called ''phlebotomy'') or intravenous therapy. In healthcare, this procedure is performed by medical labo ...

) has become the mainstay treatment option. In the U.S., according to an academic article posted in the ''Journal of Infusion Nursing'' with data published in 2010, the primary use of phlebotomy was to take blood that would one day be reinfused back into a person.

In alternative medicine

Though bloodletting as a general health measure has been shown to be pseudoscience, it is still commonly indicated for a wide variety of conditions in theAyurvedic

Ayurveda () is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. Ayurveda is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population rep ...

, Unani

Unani or Yunani medicine (Urdu: ''tibb yūnānī'') is Perso-Arabic traditional medicine as practiced in Muslim culture in South Asia and modern day Central Asia. Unani medicine is pseudoscientific. The Indian Medical Association describes U ...

, and traditional Chinese

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays or ...

systems of alternative medicine

Alternative medicine is any practice that aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine despite lacking biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or evidence from clinical trials. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and alt ...

.Ayurveda – Panchakarma, holistic-online.com.Ayurveda

, Cancer.org.

/ref>Treating Herpes Zoster (Shingles) with Bloodletting Therapy: Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine

Unani is based on a form of humorism, and so in that system, bloodletting is used to correct supposed humoral imbalance.

See also

*Bloodstopping

Bloodstopping refers to an American folk practice once common in the Ozarks and the Appalachians, Canadian lumbercamps and the northern woods of the United States. It was believed (and still is) that certain persons, known as ''bloodstoppers'', c ...

* Blood donation

A blood donation occurs when a person voluntarily has blood drawn and used for blood transfusion, transfusions and/or made into biopharmaceutical medications by a process called Blood fractionation, fractionation (separation of whole blood com ...

* Cupping therapy

Cupping therapy is a form of alternative medicine in which a local suction is created on the skin with the application of heated cups. Its practice mainly occurs in Asia but also in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America. Cupping has ...

* Hematology

Hematology ( always spelled haematology in British English) is the branch of medicine concerned with the study of the cause, prognosis, treatment, and prevention of diseases related to blood. It involves treating diseases that affect the produc ...

* History of medicine

The history of medicine is both a study of medicine throughout history as well as a multidisciplinary field of study that seeks to explore and understand medical practices, both past and present, throughout human societies.

More than just histo ...

* Trepanation

Trepanning, also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb ''trepan'' derives from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek , literally "borer, auger"), is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drille ...

* Humorism

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

* Fleams

A fleam, also flem, flew, flue, fleame, or phleam, was a handheld instrument used for bloodletting.

History

This name for handheld venipuncture devices first appears in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts around 1000. The name is most likely derived from ...

* Panacea

In Greek mythology, Panacea (Greek ''Πανάκεια'', Panakeia), a goddess of universal remedy, was the daughter of Asclepius and Epione. Panacea and her four sisters each performed a facet of Apollo's art:

* Panacea (the goddess of universal ...

References

Books cited

* * Carter, K. Codell (2012). ''The Decline of Therapeutic Bloodletting and the Collapse of Traditional Medicine''. New Brunswick & London: Transaction Publishers. . *Further reading

* McGrew, Roderick. ''Encyclopedia of Medical History'' (1985), brief history pp. 32–34External links

The History and Progression of Bloodletting

Huge collection of antique bloodletting instruments

"Breathing a Vein"

phisick.com 14 Nov 2011 {{Use dmy dates, date=January 2021 Blood Bleeding Medical tests Medical treatments Obsolete medical procedures Traditional medicine Pseudoscience Phlebotomy