Blackbeard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Teach (alternatively spelled Edward Thatch, – 22 November 1718), better known as Blackbeard, was an English

On 28 November 1717 Teach's two ships attacked a French merchant vessel off the coast of Saint Vincent. They each fired a broadside across its bulwarks, killing several of its crew, and forcing its captain to surrender. The ship was , a large French

On 28 November 1717 Teach's two ships attacked a French merchant vessel off the coast of Saint Vincent. They each fired a broadside across its bulwarks, killing several of its crew, and forcing its captain to surrender. The ship was , a large French

Before sailing northward on his remaining sloop to Ocracoke Inlet, Teach marooned about 25 men on a small sandy island about a league from the mainland. He may have done this to stifle any protest they made, if they guessed their captain's plans. Bonnet rescued them two days later. Teach continued on to Bath, where in June 1718—only days after Bonnet had departed with his pardon—he and his much-reduced crew received their pardon from Governor Eden.

He settled in Bath, on the eastern side of Bath Creek at Plum Point, near Eden's home. During July and August he travelled between his base in the town and his sloop off Ocracoke. Johnson's account states that he married the daughter of a local plantation owner, although there is no supporting evidence for this. Eden gave Teach permission to sail to St Thomas to seek a commission as a privateer (a useful way of removing bored and troublesome pirates from the small settlement), and Teach was given official title to his remaining sloop, which he renamed ''Adventure''. By the end of August he had returned to piracy, and in the same month the Governor of Pennsylvania issued a warrant for his arrest, but by then Teach was probably operating in

Before sailing northward on his remaining sloop to Ocracoke Inlet, Teach marooned about 25 men on a small sandy island about a league from the mainland. He may have done this to stifle any protest they made, if they guessed their captain's plans. Bonnet rescued them two days later. Teach continued on to Bath, where in June 1718—only days after Bonnet had departed with his pardon—he and his much-reduced crew received their pardon from Governor Eden.

He settled in Bath, on the eastern side of Bath Creek at Plum Point, near Eden's home. During July and August he travelled between his base in the town and his sloop off Ocracoke. Johnson's account states that he married the daughter of a local plantation owner, although there is no supporting evidence for this. Eden gave Teach permission to sail to St Thomas to seek a commission as a privateer (a useful way of removing bored and troublesome pirates from the small settlement), and Teach was given official title to his remaining sloop, which he renamed ''Adventure''. By the end of August he had returned to piracy, and in the same month the Governor of Pennsylvania issued a warrant for his arrest, but by then Teach was probably operating in

Spotswood learned that William Howard, the former quartermaster of ''Queen Anne's Revenge'', was in the area, and believing that he might know of Teach's whereabouts had him and his two slaves arrested. Spotswood had no legal authority to have pirates tried, and as a result, Howard's attorney, John Holloway, brought charges against Captain Brand of , where Howard was imprisoned. He also sued on Howard's behalf for damages of £500, claiming wrongful arrest.

Spotswood's council claimed that under a statute of William III the governor was entitled to try pirates without a jury in times of crisis and that Teach's presence was a crisis. The charges against Howard referred to several acts of piracy supposedly committed after the pardon's cut-off date, in "a sloop belonging to ye subjects of the King of Spain", but ignored the fact that they took place outside Spotswood's jurisdiction and in a vessel then legally owned. Another charge cited two attacks, one of which was the capture of a slave ship off Charles Town Bar, from which one of Howard's slaves was presumed to have come. Howard was sent to await trial before a Court of Vice-Admiralty, on the charge of piracy, but Brand and his colleague, Captain Gordon (of ) refused to serve with Holloway present. Incensed, Holloway had no option but to stand down, and was replaced by the

Spotswood learned that William Howard, the former quartermaster of ''Queen Anne's Revenge'', was in the area, and believing that he might know of Teach's whereabouts had him and his two slaves arrested. Spotswood had no legal authority to have pirates tried, and as a result, Howard's attorney, John Holloway, brought charges against Captain Brand of , where Howard was imprisoned. He also sued on Howard's behalf for damages of £500, claiming wrongful arrest.

Spotswood's council claimed that under a statute of William III the governor was entitled to try pirates without a jury in times of crisis and that Teach's presence was a crisis. The charges against Howard referred to several acts of piracy supposedly committed after the pardon's cut-off date, in "a sloop belonging to ye subjects of the King of Spain", but ignored the fact that they took place outside Spotswood's jurisdiction and in a vessel then legally owned. Another charge cited two attacks, one of which was the capture of a slave ship off Charles Town Bar, from which one of Howard's slaves was presumed to have come. Howard was sent to await trial before a Court of Vice-Admiralty, on the charge of piracy, but Brand and his colleague, Captain Gordon (of ) refused to serve with Holloway present. Incensed, Holloway had no option but to stand down, and was replaced by the

pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

who operated around the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Great ...

and the eastern coast of Britain's North American colonies. Little is known about his early life, but he may have been a sailor on privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

ships during Queen Anne's War before he settled on the Bahamian island of New Providence, a base for Captain Benjamin Hornigold, whose crew Teach joined around 1716. Hornigold placed him in command of a sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

that he had captured, and the two engaged in numerous acts of piracy. Their numbers were boosted by the addition to their fleet of two more ships, one of which was commanded by Stede Bonnet; but Hornigold retired from piracy toward the end of 1717, taking two vessels with him.

Teach captured a French slave ship known as , renamed her '' Queen Anne's Revenge'', equipped her with 40 guns, and crewed her with over 300 men. He became a renowned pirate. His nickname derived from his thick black beard and fearsome appearance; he was reported to have tied lit fuses ( slow matches) under his hat to frighten his enemies. He formed an alliance of pirates and blockaded the port of Charles Town, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint ...

, ransoming the port's inhabitants. He then ran ''Queen Anne's Revenge'' aground on a sandbar near Beaufort, North Carolina

Beaufort ( ) is a town in and the county seat of Carteret County, North Carolina, United States. Established in 1713 and incorporated in 1723, Beaufort is the fourth oldest town in North Carolina (after Bath, New Bern and Edenton).

On February ...

. He parted company with Stede Bonnet and settled in Bath, North Carolina, also known as Bath Town, where he accepted a royal pardon

In the English and British tradition, the royal prerogative of mercy is one of the historic royal prerogatives of the British monarch, by which they can grant pardons (informally known as a royal pardon) to convicted persons. The royal prerog ...

. However, he was soon back at sea, where he attracted the attention of Alexander Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood (12 December 1676 – 7 June 1740) was a British Army officer, explorer and lieutenant governor of Colonial Virginia; he is regarded as one of the most significant historical figures in British North American colonial h ...

, the Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

. Spotswood arranged for a party of soldiers and sailors to capture him; on 22 November 1718 following a ferocious battle Teach and several of his crew were killed by a small force of sailors led by Lieutenant Robert Maynard.

Teach was a shrewd and calculating leader who spurned the use of violence, relying instead on his fearsome image to elicit the response that he desired from those whom he robbed. He was romanticized after his death and became the inspiration for an archetypal pirate in works of fiction across many genres.

Early life

Little is known about Blackbeard's early life. It is commonly believed that at the time of his death he was between 35 and 40 years old and thus born in about 1680. In contemporary records his name is most often given as Blackbeard, Edward Thatch or Edward Teach; the latter is most often used. Several spellings of his surname exist—Thatch, Thach, Thache, Thack, Tack, Thatche and Theach. One early source claims that his surname was Drummond, but the lack of any supporting documentation makes this unlikely. Pirates habitually used fictitious surnames while engaged in piracy so as not to tarnish the family name, which makes it unlikely that Teach's real name will ever be known. The 17th-century rise of Britain's American colonies and the rapid 18th-century expansion of theAtlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

had made Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

an important international sea port, and Teach was most likely raised in what was then the second-largest city in England. He could almost certainly read and write; he communicated with merchants and when killed had in his possession a letter addressed to him by the Chief Justice and Secretary of the Province of Carolina, Tobias Knight. Author Robert Lee speculated that Teach may therefore have been born into a respectable, wealthy family. He may have arrived in the Caribbean in the last years of the 17th century, on a merchant vessel (possibly a slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast i ...

). The 18th-century author Charles Johnson claimed that Teach was for some time a sailor operating from Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispan ...

on privateer ships during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phili ...

, and that "he had often distinguished himself for his uncommon boldness and personal courage". It is unknown at what point during the war Teach joined the fighting, as with the record of most of his life before he became a pirate.

New Providence

With its history of colonialism, trade and piracy, the West Indies was the setting for many 17th- and 18th-century maritime incidents. The privateer-turned-pirate Henry Jennings and his followers decided, early in the 18th century, to use the uninhabited island of New Providence as a base for their operations; it was within easy reach of the Florida Strait and its busy shipping lanes, which were filled with European vessels crossing the Atlantic. New Providence's harbour could easily accommodate hundreds of ships but was too shallow for theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

's larger vessels. The author George Woodbury described New Providence as "no city of homes; it was a place of temporary sojourn and refreshment for a literally floating population," continuing, "The only permanent residents were the piratical camp followers, the traders, and the hangers-on; all others were transient." In New Providence, pirates found a welcome respite from the law.

Teach was one of those who came to enjoy the island's benefits. Probably shortly after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne of ...

, he moved there from Jamaica, and, along with most privateers once involved in the war, became involved in piracy. Possibly about 1716, he joined the crew of Captain Benjamin Hornigold, a renowned pirate who operated from New Providence's safe waters. In 1716 Hornigold placed Teach in charge of a sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

he had taken as a prize. In early 1717, Hornigold and Teach, each captaining a sloop, set out for the mainland. They captured a boat carrying 120 barrels of flour out of Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, and shortly thereafter took 100 barrels of wine from a sloop out of Bermuda

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, ...

. A few days later they stopped a vessel sailing from Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

to Charles Town, South Carolina. Teach and his quartermaster, William Howard, may at this time have struggled to control their crews. By then they had probably developed a taste for Madeira wine

Madeira is a fortified wine made on the Portuguese Madeira Islands, off the coast of Africa. Madeira is produced in a variety of styles ranging from dry wines which can be consumed on their own, as an apéritif, to sweet wines usually consu ...

, and on 29 September near Cape Charles all they took from the ''Betty'' of Virginia was her cargo of Madeira, before they scuttled her with the remaining cargo.

It was during this cruise with Hornigold that the earliest known report of Teach was made, in which he is recorded as a pirate in his own right, in command of a large crew. In a report made by a Captain Mathew Munthe on an anti-piracy patrol for North Carolina, "Thatch" was described as operating "a sloop 6 and about 70 men". In September Teach and Hornigold encountered Stede Bonnet, a landowner and military officer from a wealthy family who had turned to piracy earlier that year. Bonnet's crew of about 70 were reportedly dissatisfied with his command, so with Bonnet's permission, Teach took control of his ship ''Revenge''. The pirates' flotilla now consisted of three ships; Teach on ''Revenge'', Teach's old sloop and Hornigold's ''Ranger''. By October, another vessel had been captured and added to the small fleet. The sloops ''Robert'' of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and ''Good Intent'' of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

were stopped on 22 October 1717, and their cargo holds emptied.

As a former British privateer, Hornigold attacked only his old enemies, but for his crew, the sight of British vessels filled with valuable cargo passing by unharmed became too much, and at some point toward the end of 1717 he was demoted. Whether Teach had any involvement in this decision is unknown, but Hornigold quickly retired from piracy. He took ''Ranger'' and one of the sloops, leaving Teach with ''Revenge'' and the remaining sloop. The two never met again and, as did many other occupants of New Providence, Hornigold accepted the King's pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

.

Blackbeard

On 28 November 1717 Teach's two ships attacked a French merchant vessel off the coast of Saint Vincent. They each fired a broadside across its bulwarks, killing several of its crew, and forcing its captain to surrender. The ship was , a large French

On 28 November 1717 Teach's two ships attacked a French merchant vessel off the coast of Saint Vincent. They each fired a broadside across its bulwarks, killing several of its crew, and forcing its captain to surrender. The ship was , a large French Guineaman

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast in ...

registered in Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the A ...

and carrying a cargo of slaves. This ship had originally been the English merchantman ''Concord'', captured in 1711 by a French squadron, and then changed hands several times by 1717. Teach and his crews sailed the vessel south along Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines () is an island country in the Caribbean. It is located in the southeast Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, which lie in the West Indies at the southern end of the eastern border of the Caribbean Sea ...

to Bequia, where they disembarked her crew and cargo, and converted the ship for their own use. The crew of were given the smaller of Teach's two sloops, which they renamed ("Bad Meeting"), and sailed for Martinique. Teach may have recruited some of their slaves, but the remainder were left on the island and were later recaptured by the returning crew of .

Teach immediately renamed as ''Queen Anne's Revenge'' and equipped her with 40 guns. By this time Teach had placed his lieutenant Richards in command of Bonnet's ''Revenge''. In late November, near Saint Vincent, he attacked the ''Great Allen''. After a lengthy engagement, he forced the large and well-armed merchant ship to surrender. He ordered her to move closer to the shore, disembarked her crew and emptied her cargo holds, and then burned and sank the vessel. The incident was chronicled in the ''Boston News-Letter'', which called Teach the commander of a "French ship of 32 Guns, a Briganteen of 10 guns and a Sloop of 12 guns." It is not known when or where Teach collected the ten-gun briganteen, but by that time he may have been in command of at least 150 men split among three vessels.

On 5 December 1717 Teach stopped the merchant sloop ''Margaret'' off the coast of Crab Island, near Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The territ ...

. Her captain, Henry Bostock, and crew, remained Teach's prisoners for about eight hours, and were forced to watch as their sloop was ransacked. Bostock, who had been held aboard ''Queen Anne's Revenge'', was returned unharmed to ''Margaret'' and was allowed to leave with his crew. He returned to his base of operations on Saint Christopher Island and reported the matter to Governor Walter Hamilton, who requested that he sign an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a statemen ...

about the encounter. Bostock's deposition details Teach's command of two vessels: a sloop and a large French guineaman, Dutch-built, with 36 cannons and a crew of 300 men. The captain believed that the larger ship carried valuable gold dust, silver plate, and "a very fine cup" supposedly taken from the commander of ''Great Allen''. Teach's crew had apparently informed Bostock that they had destroyed several other vessels, and that they intended to sail to Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and t ...

and lie in wait for an expected Spanish armada, supposedly laden with money to pay the garrisons. Bostock also claimed that Teach had questioned him about the movements of local ships, but also that he had seemed unsurprised when Bostock told him of an expected royal pardon from London for all pirates.

Bostock's deposition describes Teach as a "tall spare man with a very black beard which he wore very long". It is the first recorded account of Teach's appearance and is the source of his cognomen, Blackbeard. Later descriptions mention that his thick black beard was braided into pigtails, sometimes tied in with small coloured ribbons. Johnson (1724) described him as "such a figure that imagination cannot form an idea of a fury from hell to look more frightful." Whether Johnson's description was entirely truthful or embellished is unclear, but it seems likely that Teach understood the value of appearances; better to strike fear into the heart of one's enemies, than rely on bluster alone. Teach was tall, with broad shoulders. He wore knee-length boots and dark clothing, topped with a wide hat and sometimes a long coat of brightly coloured silk or velvet. Johnson also described Teach in times of battle as wearing "a sling over his shoulders, with three brace of pistols, hanging in holsters like bandoliers; and stuck lighted slow matches under his hat", the latter apparently to emphasise the fearsome appearance he wished to present to his enemies. Despite his ferocious reputation, there are no verified accounts of his ever having murdered or harmed those he held captive. Teach may have used other aliases; on 30 November, the ''Monserrat Merchant'' encountered two ships and a sloop, commanded by a Captain Kentish and Captain Edwards (the latter a known alias of Stede Bonnet).

Enlargement of Teach's fleet

Teach's movements between late 1717 and early 1718 are not known. He and Bonnet were probably responsible for an attack offSint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius (, ), also known locally as Statia (), is an island in the Caribbean. It is a special municipality (officially " public body") of the Netherlands.

The island lies in the northern Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, s ...

in December 1717. Henry Bostock claimed to have heard the pirates say they would head toward the Spanish-controlled Samaná Bay in Hispaniola, but a cursory search revealed no pirate activity. Captain Hume of reported on 6 February that a "Pyrate Ship of 36 Guns and 250 men, and a Sloop of 10 Guns and 100 men were Said to be Cruizing amongst the Leeward Islands". Hume reinforced his crew with soldiers armed with musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket graduall ...

s, and joined up with to track the two ships, to no avail, though they discovered that the two ships had sunk a French vessel off St Christopher Island, and reported also that they had last been seen "gone down the North side of Hispaniola". Although no confirmation exists that these two ships were controlled by Teach and Bonnet, author Angus Konstam believes it very likely they were.

In March 1718, while taking on water at Turneffe Island east of Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wa ...

, both ships spotted the Jamaican logwood-cutting sloop ''Adventure'' making for the harbour. She was stopped and her captain, Harriot, invited to join the pirates. Harriot and his crew accepted the invitation, and Teach sent over a crew to sail ''Adventure'' making Israel Hands the captain. They sailed for the Bay of Honduras, where they added another ship and four sloops to their flotilla. On 9 April Teach's enlarged fleet of ships looted and burnt ''Protestant Caesar''. His fleet then sailed to Grand Cayman

Grand Cayman is the largest of the three Cayman Islands and the location of the territory's capital, George Town. In relation to the other two Cayman Islands, it is approximately 75 miles (121 km) southwest of Little Cayman and 90 miles ( ...

where they captured a "small turtler". Teach probably sailed toward Havana, where he may have captured a small Spanish vessel that had left the Cuban port. They then sailed to the wrecks of the 1715 Spanish fleet, off the eastern coast of Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

. There Teach disembarked the crew of the captured Spanish sloop, before proceeding north to the port of Charles Town, South Carolina, attacking three vessels along the way.

Blockade of Charles Town

By May 1718, Teach had awarded himself the rank of Commodore and was at the height of his power. Late that month his flotilla blockaded the port of Charles Town in theProvince of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The mona ...

. All vessels entering or leaving the port were stopped, and as the town had no guard ship, its pilot boat

A pilot boat is a type of boat used to transport maritime pilots between land and the inbound or outbound ships that they are piloting. Pilot boats were once sailing boats that had to be fast because the first pilot to reach the incoming shi ...

was the first to be captured. Over the next five or six days about nine vessels were stopped and ransacked as they attempted to sail past Charles Town Bar Charleston Bar is a series of submerged shoals lying about eight miles southeast of Charleston, South Carolina, United States.

See also

* Battle of Sullivan's Island

{{coord, 32.730, -79.851, display=title

Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Foo ...

, where Teach's fleet was anchored. One such ship, headed for London with a group of prominent Charles Town citizens which included Samuel Wragg (a member of the Council of the Province of Carolina), was the ''Crowley''. Her passengers were questioned about the vessels still in port and then locked below decks for about half a day. Teach informed the prisoners that his fleet required medical supplies from the colonial government of South Carolina, and that if none were forthcoming, all prisoners would be executed, their heads sent to the Governor

A governor is an official, usually acting as the executive of a non-sovereign level of government.

Governor may also refer to:

Leadership

* Governor (China), the head of government of a province

* Governor (Japan), the highest ranking executive ...

and all captured ships burnt.

Wragg agreed to Teach's demands, and a Mr. Marks and two pirates were given two days to collect the drugs. Teach moved his fleet, and the captured ships, to within about five or six leagues from land. Three days later a messenger, sent by Marks, returned to the fleet; Marks's boat had capsized and delayed their arrival in Charles Town. Teach granted a reprieve of two days, but still the party did not return. He then called a meeting of his fellow sailors and moved eight ships into the harbour, causing panic within the town. When Marks finally returned to the fleet, he explained what had happened. On his arrival he had presented the pirates' demands to the Governor and the drugs had been quickly gathered, but the two pirates sent to escort him had proved difficult to find; they had been busy drinking with friends and were finally discovered, drunk.

Teach kept to his side of the bargain and released the captured ships and his prisoners—albeit relieved of their valuables, including the fine clothing some had worn.

Beaufort Inlet

Whilst at Charles Town, Teach learned that Woodes Rogers had left England with several men-of-war, with orders to purge the West Indies of pirates. Teach's flotilla sailed northward along the Atlantic coast and into Topsail Inlet (commonly known as Beaufort Inlet), off the coast of North Carolina. There they intended tocareen

Careening (also known as "heaving down") is a method of gaining access to the hull of a sailing vessel without the use of a dry dock. It is used for cleaning or repairing the hull. Before ship's hulls were protected from biofouling, marine growth ...

their ships to scrape their hulls, but on 10 June 1718 the ''Queen Anne's Revenge'' ran aground on a sandbar, cracking her main-mast and severely damaging many of her timbers. Teach ordered several sloops to throw ropes across the flagship in an attempt to free her. A sloop commanded by Israel Hands of ''Adventure'' also ran aground, and both vessels appeared to be damaged beyond repair, leaving only ''Revenge'' and the captured Spanish sloop.

Pardon

Teach had at some stage learnt of the offer of a royal pardon and probably confided in Bonnet his willingness to accept it. The pardon was open to all pirates who surrendered on or before 5 September 1718, but contained a caveat stipulating that immunity was offered only against crimes committed before 5 January. Although in theory this left Bonnet and Teach at risk of being hanged for their actions at Charles Town Bar, most authorities could waive such conditions. Teach thought that Governor Charles Eden was a man he could trust, but to make sure, he waited to see what would happen to another captain. Bonnet left immediately on a small sailing boat for Bath Town, where he surrendered to Governor Eden, and received his pardon. He then travelled back to Beaufort Inlet to collect the ''Revenge'' and the remainder of his crew, intending to sail toSaint Thomas Island

Saint Thomas ( da, Sankt Thomas) is one of the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea which, together with Saint John, Water Island, Hassel Island, and Saint Croix, form a county-equivalent and constituent district of the United States Virgin I ...

to receive a commission. Unfortunately for him, Teach had stripped the vessel of its valuables and provisions, and had marooned its crew; Bonnet set out for revenge, but was unable to find him. He and his crew returned to piracy and were captured on 27 September 1718 at the mouth of the Cape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a long blackwater river in east central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River (North Ca ...

. All but four were tried and hanged in Charles Town.

The author Robert Lee surmised that Teach and Hands intentionally ran the ships aground to reduce the fleet's crew complement, increasing their share of the spoils. During the trial of Bonnet's crew, ''Revenge''s boatswain Ignatius Pell testified that "the ship was run ashore and lost, which Thatch eachcaused to be done." Lee considers it plausible that Teach let Bonnet in on his plan to accept a pardon from Governor Eden. He suggested that Bonnet do the same, and as war between the Quadruple Alliance of 1718 and Spain was threatening, to consider taking a privateer's commission from England. Lee suggests that Teach also offered Bonnet the return of his ship ''Revenge''. Konstam (2007) proposes a similar idea, explaining that Teach began to see ''Queen Anne's Revenge'' as something of a liability; while a pirate fleet was anchored, news of this was sent to neighbouring towns and colonies, and any vessels nearby would delay sailing. It was prudent therefore for Teach not to linger for too long, although wrecking the ship was a somewhat extreme measure.

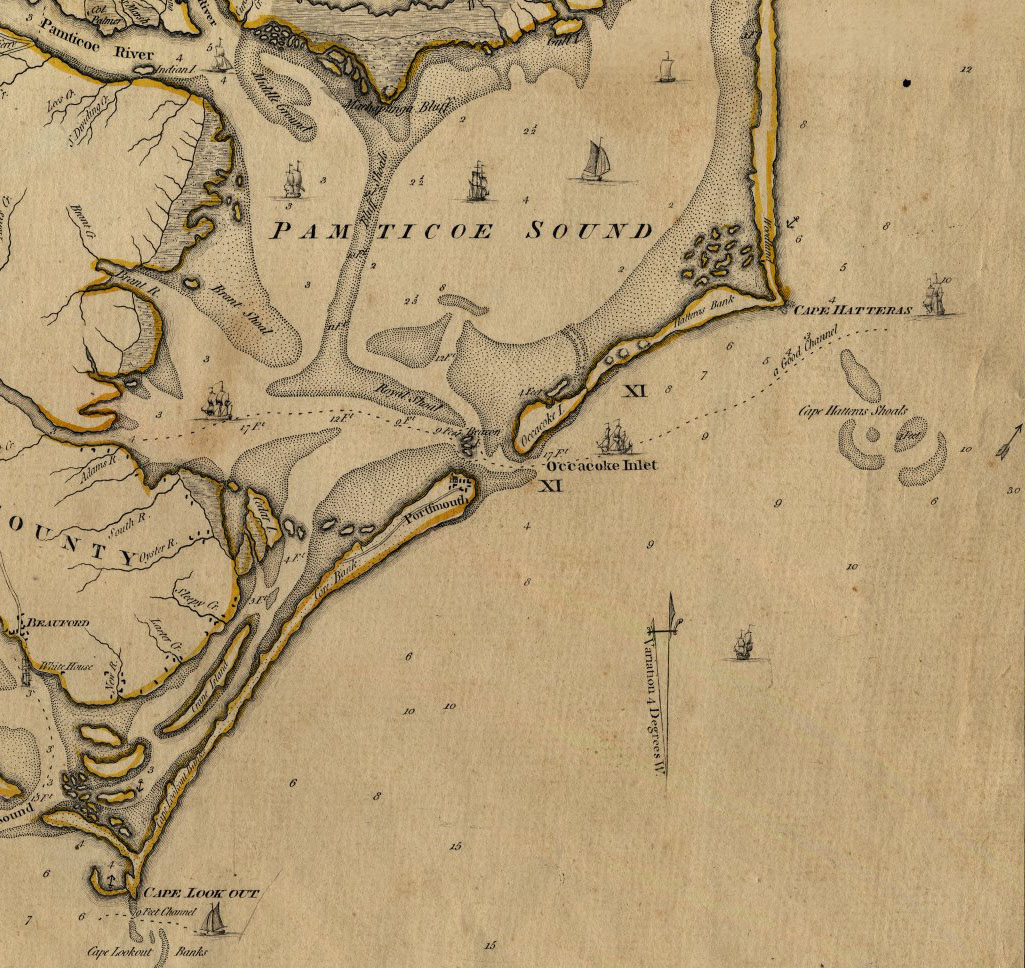

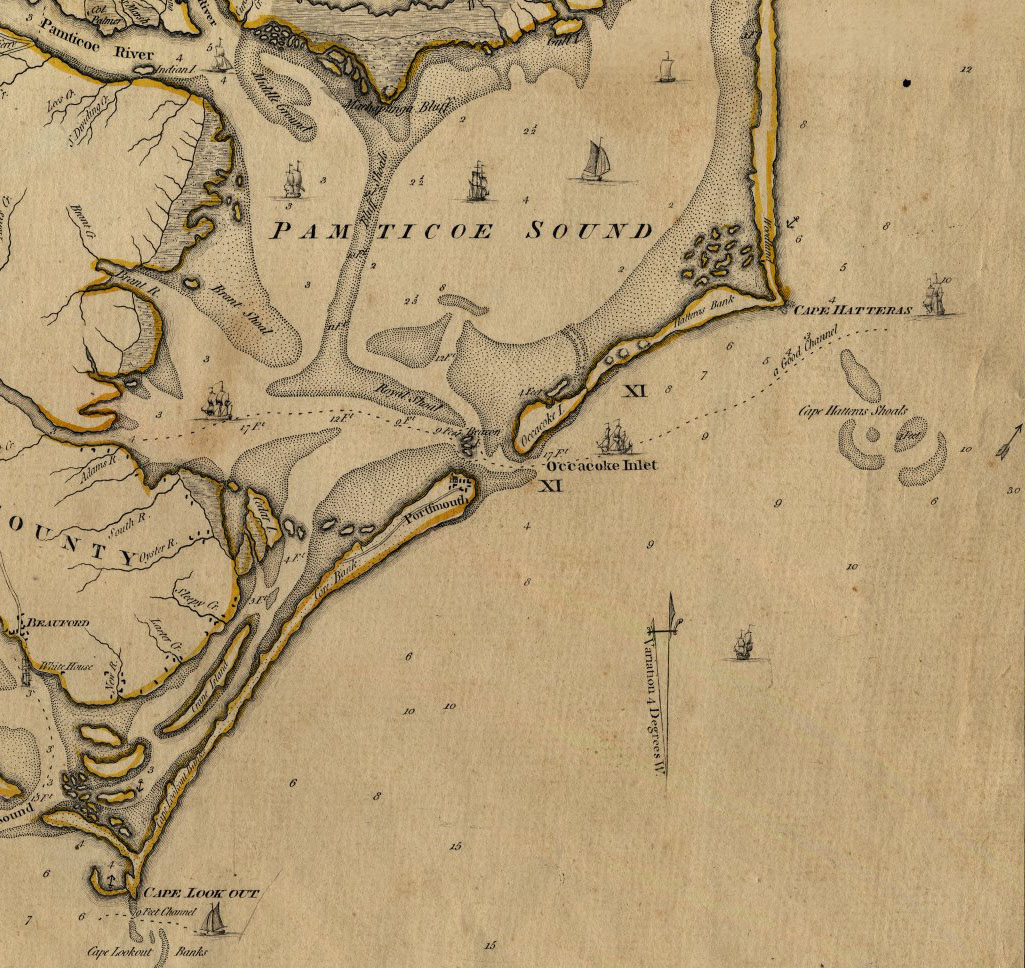

Before sailing northward on his remaining sloop to Ocracoke Inlet, Teach marooned about 25 men on a small sandy island about a league from the mainland. He may have done this to stifle any protest they made, if they guessed their captain's plans. Bonnet rescued them two days later. Teach continued on to Bath, where in June 1718—only days after Bonnet had departed with his pardon—he and his much-reduced crew received their pardon from Governor Eden.

He settled in Bath, on the eastern side of Bath Creek at Plum Point, near Eden's home. During July and August he travelled between his base in the town and his sloop off Ocracoke. Johnson's account states that he married the daughter of a local plantation owner, although there is no supporting evidence for this. Eden gave Teach permission to sail to St Thomas to seek a commission as a privateer (a useful way of removing bored and troublesome pirates from the small settlement), and Teach was given official title to his remaining sloop, which he renamed ''Adventure''. By the end of August he had returned to piracy, and in the same month the Governor of Pennsylvania issued a warrant for his arrest, but by then Teach was probably operating in

Before sailing northward on his remaining sloop to Ocracoke Inlet, Teach marooned about 25 men on a small sandy island about a league from the mainland. He may have done this to stifle any protest they made, if they guessed their captain's plans. Bonnet rescued them two days later. Teach continued on to Bath, where in June 1718—only days after Bonnet had departed with his pardon—he and his much-reduced crew received their pardon from Governor Eden.

He settled in Bath, on the eastern side of Bath Creek at Plum Point, near Eden's home. During July and August he travelled between his base in the town and his sloop off Ocracoke. Johnson's account states that he married the daughter of a local plantation owner, although there is no supporting evidence for this. Eden gave Teach permission to sail to St Thomas to seek a commission as a privateer (a useful way of removing bored and troublesome pirates from the small settlement), and Teach was given official title to his remaining sloop, which he renamed ''Adventure''. By the end of August he had returned to piracy, and in the same month the Governor of Pennsylvania issued a warrant for his arrest, but by then Teach was probably operating in Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inla ...

, some distance away. He took two French ships leaving the Caribbean, moved one crew across to the other, and sailed the remaining ship back to Ocracoke. In September he told Eden that he had found the French ship at sea, deserted. A Vice Admiralty Court was quickly convened, presided over by Tobias Knight and the Collector of Customs. The ship was judged as a derelict found at sea, and of its cargo twenty hogshead

A hogshead (abbreviated "hhd", plural "hhds") is a large cask of liquid (or, less often, of a food commodity). More specifically, it refers to a specified volume, measured in either imperial or US customary measures, primarily applied to alcoh ...

s of sugar were awarded to Knight and sixty to Eden; Teach and his crew were given what remained in the vessel's hold.

Ocracoke Inlet was Teach's favourite anchorage. It was a perfect vantage point from which to view ships travelling between the various settlements of northeast Carolina, and it was from there that Teach first spotted the approaching ship of Charles Vane, another English pirate. Several months earlier Vane had rejected the pardon brought by Woodes Rogers and escaped the men-of-war the English captain brought with him to Nassau. He had also been pursued by Teach's old commander, Benjamin Hornigold, who was by then a pirate hunter. Teach and Vane spent several nights on the southern tip of Ocracoke Island, accompanied by such notorious figures as Israel Hands, Robert Deal and Calico Jack.

Alexander Spotswood

As it spread throughout the neighbouring colonies, the news of Teach and Vane's impromptu party worried the Governor of Pennsylvania enough to send out two sloops to capture the pirates. They were unsuccessful, but Governor of VirginiaAlexander Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood (12 December 1676 – 7 June 1740) was a British Army officer, explorer and lieutenant governor of Colonial Virginia; he is regarded as one of the most significant historical figures in British North American colonial h ...

was also concerned that the supposedly retired freebooter and his crew were living in nearby North Carolina. Some of Teach's former crew had already moved into several Virginian seaport towns, prompting Spotswood to issue a proclamation on 10 July, requiring all former pirates to make themselves known to the authorities, to give up their arms and to not travel in groups larger than three. As head of a Crown colony, Spotswood viewed the proprietary colony

A proprietary colony was a type of English colony mostly in North America and in the Caribbean in the 17th century. In the British Empire, all land belonged to the monarch, and it was his/her prerogative to divide. Therefore, all colonial proper ...

of North Carolina with contempt; he had little faith in the ability of the Carolinians to control the pirates, who he suspected would be back to their old ways, disrupting Virginian commerce, as soon as their money ran out.

Spotswood learned that William Howard, the former quartermaster of ''Queen Anne's Revenge'', was in the area, and believing that he might know of Teach's whereabouts had him and his two slaves arrested. Spotswood had no legal authority to have pirates tried, and as a result, Howard's attorney, John Holloway, brought charges against Captain Brand of , where Howard was imprisoned. He also sued on Howard's behalf for damages of £500, claiming wrongful arrest.

Spotswood's council claimed that under a statute of William III the governor was entitled to try pirates without a jury in times of crisis and that Teach's presence was a crisis. The charges against Howard referred to several acts of piracy supposedly committed after the pardon's cut-off date, in "a sloop belonging to ye subjects of the King of Spain", but ignored the fact that they took place outside Spotswood's jurisdiction and in a vessel then legally owned. Another charge cited two attacks, one of which was the capture of a slave ship off Charles Town Bar, from which one of Howard's slaves was presumed to have come. Howard was sent to await trial before a Court of Vice-Admiralty, on the charge of piracy, but Brand and his colleague, Captain Gordon (of ) refused to serve with Holloway present. Incensed, Holloway had no option but to stand down, and was replaced by the

Spotswood learned that William Howard, the former quartermaster of ''Queen Anne's Revenge'', was in the area, and believing that he might know of Teach's whereabouts had him and his two slaves arrested. Spotswood had no legal authority to have pirates tried, and as a result, Howard's attorney, John Holloway, brought charges against Captain Brand of , where Howard was imprisoned. He also sued on Howard's behalf for damages of £500, claiming wrongful arrest.

Spotswood's council claimed that under a statute of William III the governor was entitled to try pirates without a jury in times of crisis and that Teach's presence was a crisis. The charges against Howard referred to several acts of piracy supposedly committed after the pardon's cut-off date, in "a sloop belonging to ye subjects of the King of Spain", but ignored the fact that they took place outside Spotswood's jurisdiction and in a vessel then legally owned. Another charge cited two attacks, one of which was the capture of a slave ship off Charles Town Bar, from which one of Howard's slaves was presumed to have come. Howard was sent to await trial before a Court of Vice-Admiralty, on the charge of piracy, but Brand and his colleague, Captain Gordon (of ) refused to serve with Holloway present. Incensed, Holloway had no option but to stand down, and was replaced by the Attorney General of Virginia

The attorney general of Virginia is an elected constitutional position that holds an executive office in the government of Virginia. Attorneys general are elected for a four-year term in the year following a presidential election. There are no ...

, John Clayton, whom Spotswood described as "an honester man han Holloway

Han may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Han Chinese, or Han People (): the name for the largest ethnic group in China, which also constitutes the world's largest ethnic group.

** Han Taiwanese (): the name for the ethnic group of the Taiwanese p ...

. Howard was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, but was saved by a commission from London, which directed Spotswood to pardon all acts of piracy committed by surrendering pirates before 18 August 1718.

Spotswood had obtained from Howard valuable information on Teach's whereabouts, and he planned to send his forces across the border into North Carolina to capture him. He gained the support of two men keen to discredit North Carolina's Governor—Edward Moseley and Colonel Maurice Moore. He also wrote to the Lords of Trade, suggesting that the Crown might benefit financially from Teach's capture. Spotswood personally financed the operation, possibly believing that Teach had fabulous treasures hidden away. He ordered Captains Gordon and Brand of HMS ''Pearl'' and HMS ''Lyme'' to travel overland to Bath. Lieutenant Robert Maynard of HMS ''Pearl'' was given command of two commandeered sloops, to approach the town from the sea. An extra incentive for Teach's capture was the offer of a reward from the Assembly of Virginia, over and above any that might be received from the Crown.

Maynard took command of the two armed sloops on 17 November. He was given 57 men—33 from HMS ''Pearl'' and 24 from HMS ''Lyme''. Maynard and the detachment from HMS ''Pearl'' took the larger of the two vessels and named her ''Jane''; the rest took ''Ranger'', commanded by one of Maynard's officers, a Mister Hyde. Some from the two ships' civilian crews remained aboard. They sailed from Kecoughtan, along the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Ches ...

, on 17 November. The two sloops moved slowly, giving Brand's force time to reach Bath. Brand set out for North Carolina six days later, arriving within three miles of Bath on 23 November. Included in Brand's force were several North Carolinians, including Colonel Moore and Captain Jeremiah Vail, sent to counter any local objection to the presence of foreign soldiers. Moore went into the town to see if Teach was there, reporting back that he was not, but that he was expected at "every minute." Brand then went to Governor Eden's home and informed him of his purpose. The next day, Brand sent two canoes down Pamlico River

The Pamlico

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the to Ocracoke Inlet, to see if Teach could be seen. They returned two days later and reported on what eventually transpired.

Maynard had kept many of his men below deck, and in anticipation of being boarded told them to prepare for close fighting. Teach watched as the gap between the vessels closed, and ordered his men to be ready. The two vessels contacted one another as the ''Adventure''s grappling hooks hit their target and several grenades, made from powder and shot-filled bottles and ignited by fuses, broke across the sloop's deck. As the smoke cleared, Teach led his men aboard, buoyant at the sight of Maynard's apparently empty ship, his men firing at the small group of men with Maynard at the

Maynard had kept many of his men below deck, and in anticipation of being boarded told them to prepare for close fighting. Teach watched as the gap between the vessels closed, and ordered his men to be ready. The two vessels contacted one another as the ''Adventure''s grappling hooks hit their target and several grenades, made from powder and shot-filled bottles and ignited by fuses, broke across the sloop's deck. As the smoke cleared, Teach led his men aboard, buoyant at the sight of Maynard's apparently empty ship, his men firing at the small group of men with Maynard at the  Maynard later examined Teach's body, noting that it had been shot five times and cut about twenty. He also found several items of correspondence, including a letter from Tobias Knight. Teach's corpse was thrown into the inlet and his head was suspended from the

Maynard later examined Teach's body, noting that it had been shot five times and cut about twenty. He also found several items of correspondence, including a letter from Tobias Knight. Teach's corpse was thrown into the inlet and his head was suspended from the

Despite his infamy, Teach was not the most successful of pirates. Henry Every retired a rich man, and Bartholomew Roberts took an estimated five times the amount Teach stole. Treasure hunters have long busied themselves searching for any trace of his rumoured hoard of gold and silver, but nothing found in the numerous sites explored along the east coast of the US has ever been connected to him. Some tales suggest that pirates often killed a prisoner on the spot where they buried their loot, and Teach is no exception in these stories, but that no finds have come to light is not exceptional; buried pirate treasure is often considered a modern myth for which almost no supporting evidence exists. The available records include nothing to suggest that the burial of treasure was a common practice, except in the imaginations of the writers of fictional accounts such as ''

Despite his infamy, Teach was not the most successful of pirates. Henry Every retired a rich man, and Bartholomew Roberts took an estimated five times the amount Teach stole. Treasure hunters have long busied themselves searching for any trace of his rumoured hoard of gold and silver, but nothing found in the numerous sites explored along the east coast of the US has ever been connected to him. Some tales suggest that pirates often killed a prisoner on the spot where they buried their loot, and Teach is no exception in these stories, but that no finds have come to light is not exceptional; buried pirate treasure is often considered a modern myth for which almost no supporting evidence exists. The available records include nothing to suggest that the burial of treasure was a common practice, except in the imaginations of the writers of fictional accounts such as ''

2006 edition

() * *

1974 edition

() * * * *

N.C Supreme Court revives lawsuit over Blackbeard’s ship and lost Spanish treasure ship

''Fayetteville Observer''

BBC Video about the potential discovery of Teach's shipImages of artefacts recovered from the shipwreck thought to be the ''Queen Anne's Revenge''

''Elite Magazine''

Blackbeard's Ship Confirmed off North Carolina

''National Geographic'' News

Blackbeard's Shipwreck

''National Geographic''

Blackbeard's Lost Ship

Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

Blackbeard: American Patriot?

Military.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Blackbeard 1680s births 1718 deaths 18th-century English people 18th-century pirates 1716 crimes 1717 crimes 1718 crimes People from Bristol American folklore English folklore English privateers English pirates History of North Carolina Pardoned pirates Recipients of British royal pardons Maritime folklore People killed in action Nicknames in crime

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the to Ocracoke Inlet, to see if Teach could be seen. They returned two days later and reported on what eventually transpired.

Last battle

Maynard found the pirates anchored on the inner side of Ocracoke Island, on the evening of 21 November. He had ascertained their position from ships he had stopped along his journey, but being unfamiliar with the local channels and shoals he decided to wait until the following morning to make his attack. He stopped all traffic from entering the inlet—preventing any warning of his presence—and posted a lookout on both sloops to ensure that Teach could not escape to sea. On the other side of the island, Teach was busy entertaining guests and had not set a lookout. With Israel Hands ashore in Bath with about 24 of ''Adventure''s sailors, he also had a much-reduced crew. Johnson (1724) reported Teach had "no more than twenty-five men on board" and that he "gave out to all the vessels that he spoke with that he had forty". "Thirteen white and six Negroes", was the number later reported by Brand to the Admiralty. At daybreak, preceded by a small boat taking soundings, Maynard's two sloops entered the channel. The small craft was quickly spotted by ''Adventure'' and fired at as soon as it was within range of her guns. While the boat made a quick retreat to the ''Jane'', Teach cut the ''Adventure''s anchor cable. His crew hoisted the sails and the ''Adventure'' manoeuvred to point her starboard guns toward Maynard's sloops, which were slowly closing the gap. Hyde moved ''Ranger'' to the port side of ''Jane'' and theUnion flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

was unfurled on each ship. ''Adventure'' then turned toward the beach of Ocracoke Island, heading for a narrow channel. What happened next is uncertain. Johnson claimed that there was an exchange of small arms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

fire following which ''Adventure'' ran aground on a sandbar, and Maynard anchored and then lightened his ship to pass over the obstacle. Another version claimed that ''Jane'' and ''Ranger'' ran aground, although Maynard made no mention of this in his log.

The ''Adventure'' eventually turned her guns on the two ships and fired. The broadside was devastating; in an instant, Maynard had lost as much as a third of his forces. About 20 on ''Jane'' were either wounded or killed and 9 on ''Ranger''. Hyde was dead and his second and third officers either dead or seriously injured. His sloop was so badly damaged that it played no further role in the attack. Contemporary accounts of what happened next are confused, but small-arms fire from ''Jane'' may have cut ''Adventure''s jib sheet

In sailing, a sheet is a line (rope, cable or chain) used to control the movable corner(s) (clews) of a sail.

Terminology

In nautical usage the term "sheet" is applied to a line or chain attached to the lower corners of a sail for the purpose ...

, causing her to lose control and run onto the sandbar. In the aftermath of Teach's overwhelming attack, ''Jane'' and ''Ranger'' may also have been grounded; the battle would have become a race to see who could float their ship first.

Maynard had kept many of his men below deck, and in anticipation of being boarded told them to prepare for close fighting. Teach watched as the gap between the vessels closed, and ordered his men to be ready. The two vessels contacted one another as the ''Adventure''s grappling hooks hit their target and several grenades, made from powder and shot-filled bottles and ignited by fuses, broke across the sloop's deck. As the smoke cleared, Teach led his men aboard, buoyant at the sight of Maynard's apparently empty ship, his men firing at the small group of men with Maynard at the

Maynard had kept many of his men below deck, and in anticipation of being boarded told them to prepare for close fighting. Teach watched as the gap between the vessels closed, and ordered his men to be ready. The two vessels contacted one another as the ''Adventure''s grappling hooks hit their target and several grenades, made from powder and shot-filled bottles and ignited by fuses, broke across the sloop's deck. As the smoke cleared, Teach led his men aboard, buoyant at the sight of Maynard's apparently empty ship, his men firing at the small group of men with Maynard at the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

.

The rest of Maynard's men then burst from the hold, shouting and firing. The plan to surprise Teach and his crew worked; the pirates were apparently taken aback at the assault. Teach rallied his men and the two groups fought across the deck, which was already slick with blood from those killed or injured by Teach's broadside. Maynard and Teach fired their flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism itself, also known ...

s at each other, then threw them away. Teach drew his cutlass and managed to break Maynard's sword. Against superior training and a slight advantage in numbers, the pirates were pushed back toward the bow, allowing the ''Jane''s crew to surround Maynard and Teach, who was by then completely isolated. As Maynard drew back to fire once again, Teach moved in to attack him, but was slashed across the neck by one of Maynard's men. Badly wounded, he was then attacked and killed by several more of Maynard's crew. The remaining pirates quickly surrendered. Those left on the ''Adventure'' were captured by the ''Ranger''s crew, including one who planned to set fire to the powder room and blow up the ship. Varying accounts exist of the battle's list of casualties; Maynard reported that 8 of his men and 12 pirates were killed. Brand reported that 10 pirates and 11 of Maynard's men were killed. Spotswood claimed ten pirates and ten of the King's men dead.

Maynard later examined Teach's body, noting that it had been shot five times and cut about twenty. He also found several items of correspondence, including a letter from Tobias Knight. Teach's corpse was thrown into the inlet and his head was suspended from the

Maynard later examined Teach's body, noting that it had been shot five times and cut about twenty. He also found several items of correspondence, including a letter from Tobias Knight. Teach's corpse was thrown into the inlet and his head was suspended from the bowsprit

The bowsprit of a sailing vessel is a spar extending forward from the vessel's prow. The bowsprit is typically held down by a bobstay that counteracts the forces from the forestays. The word ''bowsprit'' is thought to originate from the Mid ...

of Maynard's sloop so that the reward could be collected. On their return to Virginia, Teach's head was placed on a pole at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay as a warning to other pirates and a greeting to other ships, and it stood there for several years.

Legacy

Lieutenant Maynard remained at Ocracoke for several more days, making repairs and burying the dead. Teach's loot—sugar, cocoa,indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', ...

and cotton—found "in pirate sloops and ashore in a tent where the sloops lay", was sold at auction along with sugar and cotton found in Tobias Knight's barn, for £2,238. Governor Spotswood used a portion of this to pay for the entire operation. The prize money for capturing Teach was to have been about £400 (£ in ), but it was split between the crews of HMS ''Lyme'' and HMS ''Pearl''. As Captain Brand and his troops had not been the ones fighting for their lives, Maynard thought this extremely unfair. He lost much of any support he may have had though when it was discovered that he and his crew had helped themselves to about £90 of Teach's booty. The two companies did not receive their prize money for another four years, and despite his bravery Maynard was not promoted, and faded into obscurity.

The remainder of Teach's crew and former associates were found by Brand, in Bath, and were transported to Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is b ...

, where they were jailed on charges of piracy. Several were black, prompting Spotswood to ask his council what could be done about "the Circumstances of these Negroes to exempt them from undergoing the same Tryal as other pirates." Regardless, the men were tried with their comrades in Williamsburg's Capitol building, under admiralty law, on 12 March 1719. No records of the day's proceedings remain, but 14 of the 16 accused were found guilty. Of the remaining two, one proved that he had partaken of the fight out of necessity, having been on Teach's ship only as a guest at a drinking party the night before, and not as a pirate. The other, Israel Hands, was not present at the fight. He claimed that during a drinking session Teach had shot him in the knee, and that he was still covered by the royal pardon. The remaining pirates were hanged, then left to rot in gibbets along Williamsburg's Capitol Landing Road (known for some time after as "Gallows Road").

Governor Eden was certainly embarrassed by Spotswood's invasion of North Carolina, and Spotswood disavowed himself of any part of the seizure. He defended his actions, writing to Lord Carteret, a shareholder of the Province of Carolina, that he might benefit from the sale of the seized property and reminding the Earl of the number of Virginians who had died to protect his interests. He argued for the secrecy of the operation by suggesting that Eden "could contribute nothing to the Success of the Design", and told Eden that his authority to capture the pirates came from the king. Eden was heavily criticised for his involvement with Teach and was accused of being his accomplice. By criticising Eden, Spotswood intended to bolster the legitimacy of his invasion. Lee (1974) concludes that although Spotswood may have thought that the ends justified the means, he had no legal authority to invade North Carolina, to capture the pirates and to seize and auction their goods. Eden doubtless shared the same view. As Spotswood had also accused Tobias Knight of being in league with Teach, on 4 April 1719, Eden had Knight brought in for questioning. Israel Hands had, weeks earlier, testified that Knight had been on board the ''Adventure'' in August 1718, shortly after Teach had brought a French ship to North Carolina as a prize. Four pirates had testified that with Teach they had visited Knight's home to give him presents. This testimony and the letter found on Teach's body by Maynard appeared compelling, but Knight conducted his defence with competence. Despite being very sick and close to death, he questioned the reliability of Spotswood's witnesses. He claimed that Israel Hands had talked under duress, and that under North Carolinian law the other witness, an African, was unable to testify. The sugar, he argued, was stored at his house legally, and Teach had visited him only on business, in his official capacity. The board found Knight innocent of all charges. He died later that year.

Eden was annoyed that the accusations against Knight arose during a trial in which he played no part. The goods which Brand seized were officially North Carolinian property and Eden considered him a thief. The argument raged back and forth between the colonies until Eden's death on 17 March 1722. His will named one of Spotswood's opponents, John Holloway, a beneficiary. In the same year, Spotswood, who for years had fought his enemies in the House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

and the Council, was replaced by Hugh Drysdale, once Robert Walpole was convinced to act.

Modern view

Official views on pirates were sometimes quite different from those held by contemporary authors, who often described their subjects as despicable rogues of the sea. Privateers who became pirates were generally considered by the English government to be reserve naval forces, and were sometimes given active encouragement; as far back as 1581Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 ...

was knighted by Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022 ...

, when he returned to England from a round-the-world expedition with plunder worth an estimated £1,500,000. Royal pardons were regularly issued, usually when England was on the verge of war, and the public's opinion of pirates was often favourable, some considering them akin to patrons. Economist Peter Leeson believes that pirates were generally shrewd businessmen, far removed from the modern, romanticised view of them as barbarians. After Woodes Rogers' 1718 landing at New Providence and his ending of the pirate republic, piracy in the West Indies fell into terminal decline. With no easily accessible outlet to fence their stolen goods, pirates were reduced to a subsistence livelihood, and following almost a century of naval warfare between the British, French and Spanish—during which sailors could find easy employment—lone privateers found themselves outnumbered by the powerful ships employed by the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

to defend its merchant fleets. The popularity of the slave trade helped bring to an end the frontier condition of the West Indies, and in these circumstances, piracy was no longer able to flourish as it once did.

Since the end of the Golden Age of Piracy, Teach and his exploits have become the stuff of lore, inspiring books, films and even amusement park rides. Much of what is known about him can be sourced to Charles Johnson's '' A General Historie of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates'', published in Britain in 1724. A recognised authority on the pirates of his time, Johnson's descriptions of such figures as Anne Bonny

Anne Bonny (8 March 1697 – disappeared April 1721), sometimes Anne Bonney, was an Irish pirate operating in the Caribbean, and one of the few female pirates in recorded history. What little that is known of her life comes largely from Capta ...

and Mary Read were for years required reading for those interested in the subject. Readers were titillated by his stories and a second edition was quickly published, though author Angus Konstam suspects that Johnson's entry on Blackbeard was "coloured a little to make a more sensational story." ''A General Historie'', though, is generally considered to be a reliable source. Johnson may have been an assumed alias. As Johnson's accounts have been corroborated in personal and official dispatches, Lee (1974) considers that whoever he was, he had some access to official correspondence. Konstam speculates further, suggesting that Johnson may have been the English playwright Charles Johnson, the British publisher Charles Rivington

Charles Rivington (1688 – 22 February 1742) was a British publisher.

Life

The eldest son of Thurston Rivington, Rivington was born at Chesterfield, Derbyshire, in 1688. Coming to London as apprentice to a bookseller, he took over in 1711 the ...

, or the writer Daniel Defoe. In his 1951 work ''The Great Days of Piracy'', author George Woodbury wrote that Johnson is "obviously a pseudonym", continuing "one cannot help suspecting that he may have been a pirate himself."

Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure n ...

''. Such hoards would necessitate a wealthy owner, and their supposed existence ignores the command structure of a pirate vessel, in which the crew served for a share of the profit. The only pirate ever known to bury treasure was William Kidd

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd ( – 23 May 1701), was a Scottish sea captain who was commissioned as a privateer and had experience as a pirate. He was tried and executed in London in 1701 for murder a ...

; the only treasure so far recovered from Teach's exploits is that taken from the wreckage of what is presumed to be the ''Queen Anne's Revenge'', which was found in 1996. As of 2009 more than 250,000 artefacts had been recovered. A selection is on public display at the North Carolina Maritime Museum.

Various superstitious

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs and pr ...

tales exist of Teach's ghost. Unexplained lights at sea are often referred to as "Teach's light", and some recitals claim that the notorious pirate now roams the afterlife searching for his head, for fear that his friends, and the Devil, will not recognise him. A North Carolinian tale holds that Teach's skull was used as the basis for a silver drinking chalice; a local judge even claimed to have drunk from it one night in the 1930s.

The name of Blackbeard has been attached to many local attractions, such as Charleston's Blackbeard's Cove. His name and persona have also featured heavily in literature. He is the main subject of Matilda Douglas's fictional 1835 work ''Blackbeard: A page from the colonial history of Philadelphia''.

Film renditions of his life include '' Blackbeard the Pirate'' (1952) starring West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Glouce ...

native Robert Newton

Robert Guy Newton (1 June 1905 – 25 March 1956) was an English actor. Along with Errol Flynn, Newton was one of the more popular actors among the male juvenile audience of the 1940s and early 1950s, especially with British boys. Known for h ...

whose exaggerated West Country accent

West Country English is a group of English language varieties and accents used by much of the native population of South West England, the area sometimes popularly known as the West Country.

The West Country is often defined as encompassin ...

is credited with popularising the stereotypical " pirate voice", '' Blackbeard's Ghost'' (1968), '' Blackbeard: Terror at Sea'' (2005) and the 2006 Hallmark Channel

The Hallmark Channel is an American television channel owned by Crown Media Holdings, Inc., which in turn is owned by Hallmark Cards, Inc. The channel's programming is primarily targeted at families, and features a mix of television movies ...

miniseries '' Blackbeard''. Parallels have also been drawn between Johnson's Blackbeard and the character of Captain Jack Sparrow in the 2003 adventure film '' Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl''. Blackbeard is also portrayed as a central character in three TV series: by John Malkovich in ''Crossbones'' (2014), by Ray Stevenson in seasons three and four of ''Black Sails'' (2016–2017), and by Taika Waititi

Taika David Cohen (born 16 August 1975), known professionally as Taika Waititi ( ), is a New Zealand filmmaker, actor, and comedian. He is a recipient of an Academy Award, a BAFTA Award, and a Grammy Award, and has received two nominations at ...

in '' Our Flag Means Death'' (2022).

In 2015, the state government of North Carolina uploaded videos of the wreck of the ''Queen Anne's Revenge'' to its website without permission. As a result Nautilus Productions

Nautilus Productions LLC is an American video production, stock footage, and photography company incorporated in Fayetteville, North Carolina in 1997. The principals are producer/director Rick Allen and photographer Cindy Burnham. Nautilus specia ...

, the company documenting the recovery since 1998, filed suit in federal court over copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, education ...

violations and the passage of "Blackbeard's Law" by the North Carolina legislature, the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

. Before posting the videos the General Assembly passed "Blackbeard's Law", N.C. Gen Stat §121-25(b), which stated, "All photographs, video recordings, or other documentary materials of a derelict vessel or shipwreck or its contents, relics, artifacts, or historic materials in the custody of any agency of North Carolina government or its subdivisions shall be a public record pursuant to Chapter 132 of the General Statutes." On 5 November 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in '' Allen v. Cooper''. The Supreme Court subsequently ruled in the state's favor, and struck down the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act

The Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA) is a United States copyright law that attempted to abrogate sovereign immunity of states for copyright infringement. The CRCA amended 17 USC 511(a):

Unconstitutionality

The CRCA has been struck ...

, which Congress passed in 1989 to attempt to curb such infringements of copyright by states.

References

Notes Citations Bibliography * * * * *2006 edition

() * *

1974 edition

() * * * *

Further reading

* * * *External links

N.C Supreme Court revives lawsuit over Blackbeard’s ship and lost Spanish treasure ship

''Fayetteville Observer''

BBC Video about the potential discovery of Teach's ship

''Elite Magazine''

Blackbeard's Ship Confirmed off North Carolina

''National Geographic'' News

Blackbeard's Shipwreck

''National Geographic''

Blackbeard's Lost Ship

Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

Blackbeard: American Patriot?

Military.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Blackbeard 1680s births 1718 deaths 18th-century English people 18th-century pirates 1716 crimes 1717 crimes 1718 crimes People from Bristol American folklore English folklore English privateers English pirates History of North Carolina Pardoned pirates Recipients of British royal pardons Maritime folklore People killed in action Nicknames in crime