Black Wednesday on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

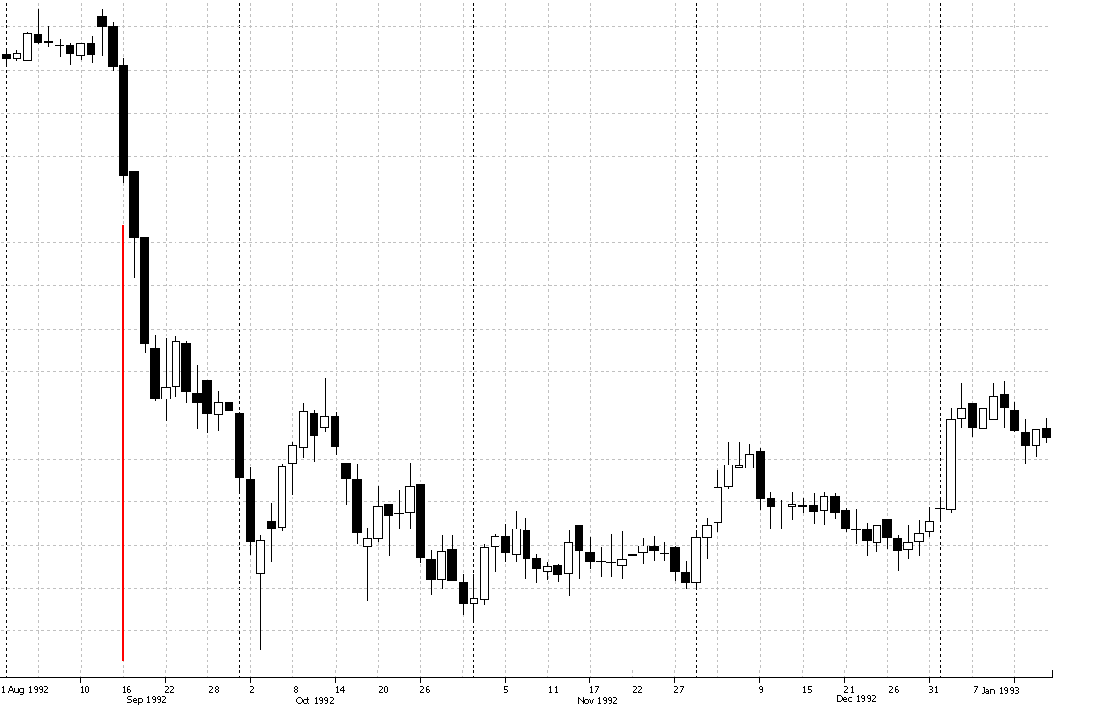

Black Wednesday (or the 1992 Sterling crisis) occurred on 16 September 1992 when the

Black Wednesday (or the 1992 Sterling crisis) occurred on 16 September 1992 when the

Black Wednesday 20 years on: how the day unfolded

''The Guardian''. Retrieved 21 October 2019. At 10:30 am on 16 September, the British government announced an increase in the base interest rate, from an already high 10%, to 12% to tempt speculators to buy pounds. Despite this and a promise later the same day to raise base rates again to 15%, dealers kept selling pounds, convinced that the government would not keep its promise. By 7:00 pm that evening, Lamont announced Britain would leave the ERM and rates would remain at the new level of 12%; however, on the next day the interest rate was back to 10%. It was later revealed that the decision to withdraw had been agreed at an emergency meeting during the day between Lamont, Major, Foreign Secretary

Black Wednesday

bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

Business School tells Ione Mako about the upside], open.edu, 24 September 2009. * {{Financial crises 1990s economic history September 1992 events in the United Kingdom Economic history of the United Kingdom George Soros John Major Short selling Wednesday Black days Stock market crashes 1992 in economics History of pound sterling

UK Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

was forced to withdraw sterling from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as ...

(ERM), after a failed attempt to keep its exchange rate above the lower limit required for the ERM participation. At that time, the United Kingdom held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union

The presidency of the Council of the European Union is responsible for the functioning of the Council of the European Union, which is the co-legislator of the EU legislature alongside the European Parliament. It rotates among the member state ...

.

The crisis damaged the credibility of the second Major ministry

John Major formed the second Major ministry following the 1992 general election after being invited by Queen Elizabeth II to begin a new administration. His government fell into minority status on 13 December 1996.

Formation

The change of ...

in handling of economic matters. The ruling Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

suffered a landslide defeat five years later at the 1997 United Kingdom general election and did not return to power until 2010. The rebounding of the UK economy in the years after Black Wednesday has been attributed to the fall in the value of sterling and the replacement of the ERM with an inflation targeting

In macroeconomics, inflation targeting is a monetary policy where a central bank follows an explicit target for the inflation rate for the medium-term and announces this inflation target to the public. The assumption is that the best that moneta ...

monetary stability policy.

Prelude

When the ERM was set up in 1979, the United Kingdom declined to join. This was a controversial decision, as the Chancellor of the Exchequer,Geoffrey Howe

Richard Edward Geoffrey Howe, Baron Howe of Aberavon, (20 December 1926 – 9 October 2015) was a British Conservative politician who served as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1989 to 1990.

Howe was Margaret Thatch ...

, was staunchly pro-European. His successor, Nigel Lawson

Nigel Lawson, Baron Lawson of Blaby, (born 11 March 1932) is a British Conservative Party politician and journalist. He was a Member of Parliament representing the constituency of Blaby from 1974 to 1992, and served in the cabinet of Margaret ...

, whilst not at all advocating a fixed exchange rate system

A fixed exchange rate, often called a pegged exchange rate, is a type of exchange rate regime in which a currency's value is fixed or pegged by a monetary authority against the value of another currency, a basket of other currencies, or another ...

, nevertheless so admired the low inflationary record of West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

as to become, by the mid-eighties, a self-styled 'exchange-rate monetarist', one viewing the Sterling-Deutschmark exchange rate as at least as reliable a guide to domestic inflation and hence to the setting of interest rates as any of the various M0-M3 measures beloved of those he labelled as " Simon Pure" monetarists. He justified this by pointing to the dependable strength of the Deutsche Mark

The Deutsche Mark (; English: ''German mark''), abbreviated "DM" or "D-Mark" (), was the official currency of West Germany from 1948 until 1990 and later the unified Germany from 1990 until the adoption of the euro in 2002. In English, it was ...

and the reliably anti-inflationary management of the Mark by the Bundesbank

The Deutsche Bundesbank (), literally "German Federal Bank", is the central bank of the Federal Republic of Germany and as such part of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Due to its strength and former size, the Bundesbank is the mos ...

, both of which he explained by citing the lasting impact in Germany of the disastrous hyperinflation of the inter-war Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

. Thus, although the UK had not joined the ERM, at Lawson's direction (and with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

's reluctant acquiescence), from early-1987 to March 1988 the Treasury followed a semi-official policy of 'shadowing' the Deutsche Mark. Matters came to a head in a clash between Lawson and Thatcher's economic adviser Alan Walters

Sir Alan Arthur Walters (17 June 1926 – 3 January 2009) was a British economist who was best known as the Chief Economic Adviser to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher from 1981 to 1983 and (after his return from the United States) again for fi ...

, when Walters claimed that the Exchange Rate Mechanism was "half baked".

This led to Lawson's resignation as Chancellor; he was replaced by former Treasury Chief Secretary John Major who, with Douglas Hurd

Douglas Richard Hurd, Baron Hurd of Westwell, (born 8 March 1930) is a British Conservative Party politician who served in the governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major from 1979 to 1995.

A career diplomat and political secretary to P ...

, the then Foreign Secretary, convinced the Cabinet to sign Britain up to the ERM in October 1990, effectively guaranteeing that the UK Government would follow an economic and monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

preventing the exchange rate between the pound and other member currencies from fluctuating by more than 6%. On 8 October 1990, Thatcher entered the pound into the ERM at DM 2.95 to £1. Hence, if the exchange rate ever neared the bottom of its permitted range, DM 2.773 (€1.4178 at the DM/Euro conversion rate), the government would be obliged to intervene. In 1989, the UK had inflation three times the rate of Germany, higher interest rates at 15%, and much lower labour productivity than France and Germany, which indicated the UK's different economic state in comparison to other ERM countries.

From the beginning of the 1990s, high German interest rates, set by the Bundesbank to counteract inflationary effects related to excess expenditure on German reunification, caused significant stress across the whole of the ERM. The UK and Italy had additional difficulties with their double deficits, while the UK was also hurt by the rapid depreciation of the United States dollar – a currency in which many British exports were priced – that summer. Issues of national prestige and the commitment to a doctrine that the fixing of exchange rates within the ERM was a pathway to a single European currency inhibited the adjustment of exchange rates. In the wake of the rejection of the Maastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Communities, ...

by the Danish electorate in a referendum in the spring of 1992, and an announcement that there would be a referendum in France as well, those ERM currencies that were trading close to the bottom of their ERM bands came under pressure from foreign exchange traders.

In the months leading up to Black Wednesday, among many other currency traders, George Soros

George Soros ( name written in eastern order), (born György Schwartz, August 12, 1930) is a Hungarian-American businessman and philanthropist. , he had a net worth of US$8.6 billion, Note that this site is updated daily. having donated mo ...

had been building a huge short position

In finance, being short in an asset means investing in such a way that the investor will profit if the value of the asset falls. This is the opposite of a more conventional "long" position, where the investor will profit if the value of the ...

in sterling that would become immensely profitable if the currency fell below the lower band of the ERM. Soros believed the rate at which the United Kingdom was brought into the Exchange Rate Mechanism was too high, inflation was too high (triple the German rate), and British interest rates were hurting their asset prices.

The currency traders act

The UK government attempted to prop up the depreciating pound to avoid withdrawal from the monetary system the country had joined only two years earlier. John Major authorised the spending of billions of pounds worth of foreign currency reserves to buy up sterling being sold on the currency markets. These measures failed to prevent the pound falling below its minimum level in the ERM. The Treasury took the decision to defend sterling's position, believing that to devalue would promote inflation. Remarks byBundesbank

The Deutsche Bundesbank (), literally "German Federal Bank", is the central bank of the Federal Republic of Germany and as such part of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Due to its strength and former size, the Bundesbank is the mos ...

President Helmut Schlesinger

Helmut Schlesinger (born 4 September 1924 in Penzberg) is a German economist and former President of the Bundesbank.

Education

After his military duty, he studied economics at the University of Munich, from where he graduated with a Diplom in ...

triggered the attack on the pound. An interview of Schlesinger by the Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

was reported by the German financial paper Handelsblatt

The ''Handelsblatt'' (literally "commerce paper" in English) is a German-language business newspaper published in Düsseldorf by Handelsblatt Media Group, formerly known as Verlagsgruppe Handelsblatt.

History and profile

''Handelsblatt'' was es ...

. In the evening of the 15 September 1992, the headline was already circulating. Schlesinger said he thought he was speaking off the record. He told the journalist that "a more comprehensive realignment" of currencies would be needed, following a recent devaluation of the Italian lira. Schlesinger later wrote that he stated a fact and this could not have triggered the crisis. This remark hugely increased pressure on the pound leading to large sterling sales.

Currency traders began a massive sell-off of pounds on Tuesday 16 September 1992. The Exchange Rate Mechanism required the Bank of England to accept any offers to sell pounds. However, the Bank of England only accepted orders during the trading day. When the markets opened in London the next morning, the Bank of England began their attempt to prop up their currency, as decided by Norman Lamont

Norman Stewart Hughson Lamont, Baron Lamont of Lerwick, (born 8 May 1942) is a British politician and former Conservative MP for Kingston-upon-Thames. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1990 until 1993. He was created a life peer in ...

( Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Robin Leigh-Pemberton (Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent grooming their successor. The governor of the Ba ...

). They began accepting orders of £300 million twice before 8:30 am, but to little effect. The Bank of England's intervention was ineffective because traders were dumping pounds far faster. The Bank of England continued to buy, and traders continued to sell, until Lamont told Prime Minister John Major that their pound purchasing was failing to produce results.Inman, Phillip (13 September 2012)Black Wednesday 20 years on: how the day unfolded

''The Guardian''. Retrieved 21 October 2019. At 10:30 am on 16 September, the British government announced an increase in the base interest rate, from an already high 10%, to 12% to tempt speculators to buy pounds. Despite this and a promise later the same day to raise base rates again to 15%, dealers kept selling pounds, convinced that the government would not keep its promise. By 7:00 pm that evening, Lamont announced Britain would leave the ERM and rates would remain at the new level of 12%; however, on the next day the interest rate was back to 10%. It was later revealed that the decision to withdraw had been agreed at an emergency meeting during the day between Lamont, Major, Foreign Secretary

Douglas Hurd

Douglas Richard Hurd, Baron Hurd of Westwell, (born 8 March 1930) is a British Conservative Party politician who served in the governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major from 1979 to 1995.

A career diplomat and political secretary to P ...

, President of the Board of Trade Michael Heseltine

Michael Ray Dibdin Heseltine, Baron Heseltine, (; born 21 March 1933) is a British politician and businessman. Having begun his career as a property developer, he became one of the founders of the publishing house Haymarket. Heseltine served ...

, and Home Secretary Kenneth Clarke

Kenneth Harry Clarke, Baron Clarke of Nottingham, (born 2 July 1940), often known as Ken Clarke, is a British politician who served as Home Secretary from 1992 to 1993 and Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1993 to 1997 as well as serving as de ...

(the latter three all being staunch pro-Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (2004) ...

as well as senior Cabinet Ministers), and that the interest rate hike to 15% had only been a temporary measure to prevent a rout in the pound that afternoon.

Aftermath

Other ERM countries such as Italy, whose currencies had breached their bands during the day, returned to the system with broadened bands or with adjusted central parities. The effect of the low German interest rates, and high British interest rates, had arguably put Britain into recession as large numbers of businesses failed and the housing market crashed. Some commentators, followingNorman Tebbit

Norman Beresford Tebbit, Baron Tebbit (born 29 March 1931) is a British politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet from 1981 to 1987 as Secretary of State for Employment (1981–1983), Secretary of State for Trad ...

, took to referring to ERM as an "Eternal Recession Mechanism" after the UK fell into recession during the early 1990s. While many people in the UK recall Black Wednesday as a national disaster that permanently affected the country's international prestige, some Conservatives claim that the forced ejection from the ERM was a "Golden Wednesday" or "White Wednesday", the day that paved the way for an economic revival, with the Conservatives handing Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

's New Labour a much stronger economy in 1997 than had existed in 1992 as the new economic policy swiftly devised in the aftermath of Black Wednesday led to re-establishment of economic growth with falling unemployment and inflation. Monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

switched to inflation targeting

In macroeconomics, inflation targeting is a monetary policy where a central bank follows an explicit target for the inflation rate for the medium-term and announces this inflation target to the public. The assumption is that the best that moneta ...

.

The Conservative Party government's reputation for economic excellence had been damaged to the extent that the electorate was more inclined to support a claim of the opposition of the time – that the economic recovery ought to be credited to external factors, as opposed to government policies implemented by the Conservatives. The Conservatives had recently won the 1992 general election, and the Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its bu ...

for September showed a small lead of 2.5% for the Conservative Party. By the October poll, following Black Wednesday, their share of the intended vote in the poll had plunged from 43% to 29%. The Conservative government then suffered a string of by-election defeats which saw its 21-seat majority eroded by December 1996. The party's performances in local government elections were similarly dismal during this time, while Labour made huge gains.

Black Wednesday was a major factor in the Conservatives finally losing the 1997 general election to Labour, who won by a landslide under the leadership of Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

. The Conservatives failed to gain significant ground at the 2001 general election under the leadership of William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, with Labour winning another landslide majority. The Conservatives did not take Government again until David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

led them to victory in the 2010 general election, 13 years later. Five years later in 2015, the party won its first overall majority 23 years after its last in 1992, five months before the crisis.

George Soros

George Soros ( name written in eastern order), (born György Schwartz, August 12, 1930) is a Hungarian-American businessman and philanthropist. , he had a net worth of US$8.6 billion, Note that this site is updated daily. having donated mo ...

made over £1 billion in profit by short selling

In finance, being short in an asset means investing in such a way that the investor will profit if the value of the asset falls. This is the opposite of a more conventional "long" position, where the investor will profit if the value of the ...

sterling.

The cost of Black Wednesday

In 1997, theUK Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ec ...

estimated the cost of Black Wednesday at £3.14 billion, which was revised to £3.3 billion in 2005, following documents released under the Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

(earlier estimates placed losses at a much higher range of £13–27 billion). Trading losses in August and September made up a minority of the losses (estimated at £800 million) and the majority of the loss to the central bank arose from non-realised profits of a potential devaluation

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national curren ...

. Treasury papers suggested that, had the government maintained $24 billion foreign currency reserves and the pound had fallen by the same amount, the UK might have made a £2.4 billion profit on sterling's devaluation.

See also

* Impossible trinity *Sale of UK gold reserves, 1999–2002

The sale of UK gold reserves was a policy pursued by HM Treasury over the period between 1999 and 2002, when gold prices were at their lowest in 20 years, following an extended bear market. The period itself has been dubbed by some commentators ...

* Sterling crisis, other currency crises in British history

Footnotes

External links

Black Wednesday

bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

Business School tells Ione Mako about the upside], open.edu, 24 September 2009. * {{Financial crises 1990s economic history September 1992 events in the United Kingdom Economic history of the United Kingdom George Soros John Major Short selling Wednesday Black days Stock market crashes 1992 in economics History of pound sterling