birth control movement in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The birth control movement in the United States was a

Although contraceptives were relatively common in middle-class and upper-class society, the topic was rarely discussed in public. The first book published in the United States which ventured to discuss contraception was ''Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question'', published by

Although contraceptives were relatively common in middle-class and upper-class society, the topic was rarely discussed in public. The first book published in the United States which ventured to discuss contraception was ''Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question'', published by

Contraception was legal in the United States throughout most of the 19th century, but in the 1870s a

Contraception was legal in the United States throughout most of the 19th century, but in the 1870s a

Under the influence of Goldman and the Free Speech League, Sanger became determined to challenge the Comstock laws that outlawed the dissemination of contraceptive information.McCann (2010), pp. 750–751. With that goal in mind, in 1914 she launched ''The Woman Rebel'', an eight-page monthly newsletter which promoted contraception using the slogan "No Gods, No Masters", and proclaimed that each woman should be "the absolute mistress of her own body." Sanger coined the term ''birth control'', which first appeared in the pages of ''Rebel'', as a more candid alternative to euphemisms such as ''family limitation''.

Sanger's goal of challenging the law was fulfilled when she was indicted in August 1914, but the prosecutors focused their attention on articles Sanger had written on assassination and marriage, rather than contraception. Afraid that she might be sent to prison without an opportunity to argue for birth control in court, she fled to England to escape arrest.

While Sanger was in Europe, her husband continued her work, which led to his arrest after he distributed a copy of a birth control pamphlet to an undercover postal worker. The arrest and his 30-day jail sentence prompted several mainstream publications, including ''

Under the influence of Goldman and the Free Speech League, Sanger became determined to challenge the Comstock laws that outlawed the dissemination of contraceptive information.McCann (2010), pp. 750–751. With that goal in mind, in 1914 she launched ''The Woman Rebel'', an eight-page monthly newsletter which promoted contraception using the slogan "No Gods, No Masters", and proclaimed that each woman should be "the absolute mistress of her own body." Sanger coined the term ''birth control'', which first appeared in the pages of ''Rebel'', as a more candid alternative to euphemisms such as ''family limitation''.

Sanger's goal of challenging the law was fulfilled when she was indicted in August 1914, but the prosecutors focused their attention on articles Sanger had written on assassination and marriage, rather than contraception. Afraid that she might be sent to prison without an opportunity to argue for birth control in court, she fled to England to escape arrest.

While Sanger was in Europe, her husband continued her work, which led to his arrest after he distributed a copy of a birth control pamphlet to an undercover postal worker. The arrest and his 30-day jail sentence prompted several mainstream publications, including ''

During Sanger's 1916 speaking tour, she promoted birth control clinics based on the Dutch model she had observed during her 1914 trip to Europe. Although she inspired many local communities to create birth control leagues, no clinics were established. Sanger therefore resolved to create a birth control clinic in New York that would provide free contraceptive services to women. New York state law prohibited the distribution of contraceptives or even contraceptive information, but Sanger hoped to exploit a provision in the law which permitted doctors to prescribe contraceptives for the prevention of disease. On October 16, 1916, she, partnering with

During Sanger's 1916 speaking tour, she promoted birth control clinics based on the Dutch model she had observed during her 1914 trip to Europe. Although she inspired many local communities to create birth control leagues, no clinics were established. Sanger therefore resolved to create a birth control clinic in New York that would provide free contraceptive services to women. New York state law prohibited the distribution of contraceptives or even contraceptive information, but Sanger hoped to exploit a provision in the law which permitted doctors to prescribe contraceptives for the prevention of disease. On October 16, 1916, she, partnering with

Engelman, p. 91. She served a sentence of 30 days in jail. In protest to her arrest as well, Byrne was sentenced to 30 days in jail at Blackwell's Island Prison and responded to her situation with a hunger strike protest. With no signs of ending her demonstration anytime soon, Byrne was force fed by prison guards. Weakened and ill, Byrne refused to end her hunger strike at the cost of securing early release from prison. However, Sanger accepted the plea bargain on her sister's behalf, agreeing that Byrne would be released early from prison if she ended her birth control activism. Horrified, Byrne's relationship quickly eroded with her sister and, both forcefully and willingly, she left the birth control movement. Due to the drama of Byrne's demonstration, the birth control movement became a headline news story in which the organization's purpose was distributed across the country. Other activists were also pushing for progress. Emma Goldman was arrested in 1916 for circulating birth control information, and

The publicity from Sanger's trial and Byrne's hunger strike generated immense enthusiasm for the cause, and by the end of 1917 there were over 30 birth control organizations in the United States. Sanger was always astute about public relations, and she seized on the publicity of the trial to advance her causes. After her trial, she emerged as the movement's most visible leader. Other leaders, such as William J. Robinson, Mary Dennett, and

The publicity from Sanger's trial and Byrne's hunger strike generated immense enthusiasm for the cause, and by the end of 1917 there were over 30 birth control organizations in the United States. Sanger was always astute about public relations, and she seized on the publicity of the trial to advance her causes. After her trial, she emerged as the movement's most visible leader. Other leaders, such as William J. Robinson, Mary Dennett, and

Engelman, pp. 113–115. Sanger, a proponent of diaphragms, was concerned that unrestricted access would result in ill-fitting diaphragms and would lead to medical

Following the successful opening of the CRB in 1923, public discussion of contraception became more commonplace, and the term "birth control" became firmly established in the nation's vernacular. Of the hundreds of references to birth control in magazines and newspapers of the 1920s, more than two-thirds were favorable.Engelman, p. 142. The availability of contraception signaled the end of the stricter morality of the

Following the successful opening of the CRB in 1923, public discussion of contraception became more commonplace, and the term "birth control" became firmly established in the nation's vernacular. Of the hundreds of references to birth control in magazines and newspapers of the 1920s, more than two-thirds were favorable.Engelman, p. 142. The availability of contraception signaled the end of the stricter morality of the

Before the advent of the birth control movement,

Before the advent of the birth control movement,  In spite of these suspicions, many African-American leaders supported efforts to supply birth control to the African-American community. In 1929, James H. Hubert, a black social worker and leader of New York's

In spite of these suspicions, many African-American leaders supported efforts to supply birth control to the African-American community. In 1929, James H. Hubert, a black social worker and leader of New York's

Two important legal decisions in the 1930s helped increase the accessibility of contraceptives. In 1930, two condom manufacturers sued each other in the ''Youngs Rubber'' case, and the judge ruled that contraceptive manufacturing was a legitimate business enterprise. He went further, and declared that the federal law prohibiting the mailing of condoms was not legally sound. Sanger precipitated a second legal breakthrough when she ordered a diaphragm from Japan in 1932, hoping to provoke a decisive battle in the courts. The diaphragm was confiscated by the U.S. government, and Sanger's subsequent legal challenge led to the 1936 '' One Package'' legal ruling by Judge Augustus Hand. His decision overturned an important provision of the anti-contraception laws that prohibited physicians from obtaining contraceptives. This court victory motivated the

Two important legal decisions in the 1930s helped increase the accessibility of contraceptives. In 1930, two condom manufacturers sued each other in the ''Youngs Rubber'' case, and the judge ruled that contraceptive manufacturing was a legitimate business enterprise. He went further, and declared that the federal law prohibiting the mailing of condoms was not legally sound. Sanger precipitated a second legal breakthrough when she ordered a diaphragm from Japan in 1932, hoping to provoke a decisive battle in the courts. The diaphragm was confiscated by the U.S. government, and Sanger's subsequent legal challenge led to the 1936 '' One Package'' legal ruling by Judge Augustus Hand. His decision overturned an important provision of the anti-contraception laws that prohibited physicians from obtaining contraceptives. This court victory motivated the

410 U.S. 113

(1972). Findlaw.com. Retrieved 26 January 2007. Also in 1970,

Also in 1970,

"Fact Sheet: Title X Family Planning Program"

January 2008. Without publicly funded family planning services, according to the

Gold RB, Sonfield A, Richards C, et al., ''Next Steps for America's Family Planning Program: Leveraging the Potential of Medicaid and Title X in an Evolving Health Care System'', Guttmacher Institute, 2009; and

Frost J, Finer L, Tapales A., "The impact of publicly funded family planning clinic services on unintended pregnancies and government cost savings", ''

Mifepristone is still used for contraception in Russia and China.

Ebadi, Manuchair, "Mifepristone" in ''Desk Reference of Clinical Pharmacology'', CRC Press, 2007, p. 443, .

Mifeprex prescribing information (label)

Retrieved 24 January 2012.

Retrieved 24 January 2012.

28 September 2000. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

''The Sex Side of Life''

published by author. via Google Books. * Dennett, Mary (1926), ''Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Abolish Them, or Change Them?'', Frederick H. Hitchcock. * Dickinson, Robert Latou (1942), ''Techniques of Contraception Control'', Williams & Wilkins. * A publication about birth control

View original copy.

* Owen, Robert Dale (1831), ''Moral Physiology, or A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question''

1842 edition, (Internet Archive)

* Sanger, Margaret (1911), ''What Every Mother Should Know'', based on a series of articles Sanger published in 1911 in the ''

1921 edition, Michigan State University

* Sanger, Margaret (1914), ''Family Limitation'', a 16-page pamphlet; also published in several later editions

1917, 6th edition, Michigan State University

* Sanger, Margaret (1916), ''What Every Girl Should Know'', Max N. Maisel; 91 pages; also published in several later editions

1920 edition, Michigan State University1922 edition, Michigan State University

* Sanger, Margaret (1920), ''Woman and the New Race'', Truth Publishing, foreword by Havelock Ellis

Harvard UniversityProject GutenbergInternet Archive

* Sanger, Margaret (1921), "The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda", ''Birth Control Review'' (April, 1921): 5. * Sanger, Margaret (1922), ''The Pivot of Civilization'', Brentanos

1922 edition, Project Gutenberg1922 edition, Internet Archive

* Stone, Hannah (1925), ''Contraceptive Methods – A Clinical Survey'', ABCL.

The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at New York University

*Bassett, Laura (February 14, 2013)

''

social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

campaign beginning in 1914 that aimed to increase the availability of contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

in the U.S. through education and legalization. The movement began in 1914 when a group of political radicals in New York City, led by Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, Mary Dennett

Mary Coffin Ware Dennett (April 4, 1872 – July 25, 1947) was an American women's rights activist, pacifist, homeopathic advocate, and pioneer in the areas of birth control, sex education, and women's suffrage. She co-founded the National ...

, and Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

, became concerned about the hardships that childbirth and self-induced abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

s brought to low-income women. Since contraception was considered to be obscene at the time, the activists targeted the Comstock laws

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of ...

, which prohibited distribution of any "obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious" materials through the mail. Hoping to provoke a favorable legal decision, Sanger deliberately broke the law by distributing ''The Woman Rebel

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth contro ...

'', a newsletter containing a discussion of contraception. In 1916, Sanger opened the first birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambulatory care clinic) is a health facility that is primarily focused on the care of outpatients. Clinics can be privately operated or publicly managed and funded. They typically cover the primary care needs ...

in the United States, but the clinic was immediately shut down by police, and Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

A major turning point for the movement came during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when many U.S. servicemen were diagnosed with venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral se ...

s. The government's response included an anti-venereal disease campaign that framed sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal penetrat ...

and contraception as issues of public health and legitimate topics of scientific research. This was the first time a U.S. government institution had engaged in a sustained, public discussion of sexual matters; as a consequence, contraception transformed from an issue of morals to an issue of public health.

Encouraged by the public's changing attitudes towards birth control, Sanger opened a second birth control clinic in 1923, but this time there were no arrests or controversy. Throughout the 1920s, public discussion of contraception became more commonplace, and the term "birth control" became firmly established in the nation's vernacular. The widespread availability of contraception signaled a transition from the stricter sexual mores

Sexual ethics (also known as sex ethics or sexual morality) is a branch of philosophy that considers the ethics or morality or otherwise in sexual behavior. Sexual ethics seeks to understand, evaluate and critique interpersonal relationships and ...

of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

to a more sexually permissive society.

Legal victories in the 1930s continued to weaken anti-contraception laws. The court victories motivated the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's state ...

in 1937 to adopt contraception as a core component of medical school curricula, but the medical community was slow to accept this new responsibility, and women continued to rely on unsafe and ineffective contraceptive advice from ill-informed sources. In 1942, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (PPFA), or simply Planned Parenthood, is a nonprofit organization that provides reproductive health care in the United States and globally. It is a tax-exempt corporation under Internal Reven ...

was formed, creating a nationwide network of birth control clinics. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the movement to legalize birth control came to a gradual conclusion, as birth control was fully embraced by the medical profession, and the remaining anti-contraception laws were no longer enforced.

Contraception in the nineteenth century

Birth control practices

The practice ofbirth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

was common throughout the U.S. prior to 1914, when the movement to legalize contraception began. Longstanding techniques included the rhythm method

Calendar-based methods are various methods of estimating a woman's likelihood of fertility, based on a record of the length of previous menstrual cycles. Various methods are known as the Knaus–Ogino method and the rhythm method. The standard days ...

, withdrawal

Withdrawal means "an act of taking out" and may refer to:

* Anchoresis (withdrawal from the world for religious or ethical reasons)

* ''Coitus interruptus'' (the withdrawal method)

* Drug withdrawal

* Social withdrawal

* Taking of money from a ban ...

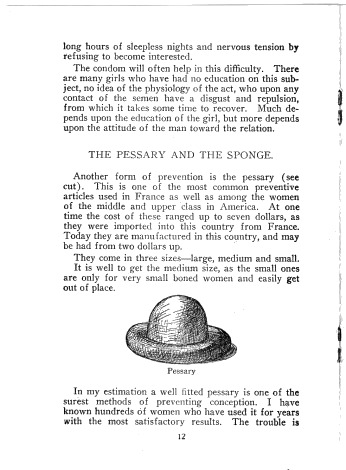

, diaphragms, contraceptive sponge

The contraceptive sponge combines barrier and spermicidal methods to prevent conception. Sponges work in two ways. First, the sponge is inserted into the vagina, so it can cover the cervix and prevent any sperm from entering the uterus. Secondly ...

s, condom

A condom is a sheath-shaped barrier device used during sexual intercourse to reduce the probability of pregnancy or a sexually transmitted infection (STI). There are both male and female condoms. With proper use—and use at every act of in ...

s, prolonged breastfeeding, and spermicides

Spermicide is a contraceptive substance that destroys sperm, inserted vaginally prior to intercourse to prevent pregnancy. As a contraceptive, spermicide may be used alone. However, the pregnancy rate experienced by couples using only spermic ...

. Use of contraceptive

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

s increased throughout the nineteenth century, contributing to a 50 percent drop in the fertility rate

The total fertility rate (TFR) of a population is the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime if:

# she were to experience the exact current age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) through her lifetime

# she were t ...

in the United States between 1800 and 1900, particularly in urban regions. The only known survey conducted during the nineteenth century of American women's contraceptive habits was performed by Clelia Mosher

Clelia Duel Mosher (KLEEL-ya DUE-el MOE-sher; December 16, 1863 – December 21, 1940) was a physician, hygienist and women's health advocate who disapproved of Victorian morality, Victorian stereotypes about the physical incapacities of women.St ...

from 1892 to 1912. The survey was based on a small sample of upper-class women, and shows that most of the women used contraception (primarily douching, but also withdrawal, rhythm, condoms and pessaries

A pessary is a prosthetic device inserted into the vagina for structural and pharmaceutical purposes. It is most commonly used to treat Stress incontinence, stress urinary incontinence to stop urinary leakage and to treat pelvic organ prolapse to ...

) and that they viewed sex as a pleasurable act that could be undertaken without the goal of procreation.

Although contraceptives were relatively common in middle-class and upper-class society, the topic was rarely discussed in public. The first book published in the United States which ventured to discuss contraception was ''Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question'', published by

Although contraceptives were relatively common in middle-class and upper-class society, the topic was rarely discussed in public. The first book published in the United States which ventured to discuss contraception was ''Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question'', published by Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the Ind ...

in 1831. The book suggested that family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marita ...

was a laudable effort, and that sexual gratification – without the goal of reproduction – was not immoral. Owen recommended withdrawal, but he also discussed sponges and condoms. That book was followed by ''Fruits of Philosophy

Charles Knowlton (May 10, 1800 – February 20, 1850) was an American physician and writer. He was an atheist.

Education

Knowlton was born May 10, 1800 in Templeton, Massachusetts. His parents were Stephen and Comfort (White) Knowlton; his ...

: The Private Companion of Young Married People'', written in 1832 by Charles Knowlton

Charles Knowlton (May 10, 1800 – February 20, 1850) was an American physician and writer. He was an atheist.

Education

Knowlton was born May 10, 1800 in Templeton, Massachusetts. His parents were Stephen and Comfort (White) Knowlton; his ...

, which recommended douching

A douche is a device used to introduce a stream of water into the body for medical or hygienic reasons, or the stream of water itself. Douche usually refers to vaginal irrigation, the rinsing of the vagina, but it can also refer to the rinsing ...

. Knowlton was prosecuted in Massachusetts on obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be use ...

charges, and served three months in prison. A third early american novel on both prevention of conception and abortion was the book ''The married woman's private medical companion: embracing the treatment of menstruation, or monthly turns, during their stoppage, irregularity, or entire suppression: pregnancy, and how it may be determined, with the treatment of its various diseases: discovery to prevent pregnancy, its great and important necessity where malformation or inability exists to give birth: to prevent miscarriage or abortion when proper and necessary, to effect miscarriage when attended with entire safety: causes and mode of cure of barrenness or sterility'', written by A. M Mauriceau in the year 1847. Mauriceau was a doctor and his work was cited many times in early volumes of the ''Birth Control Review.''

Birth control practices were generally adopted earlier in Europe than in the United States. Knowlton's book was reprinted in 1877 in England by Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (; 26 September 1833 – 30 January 1891) was an English political activist and atheist. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866, 15 years after George Holyoake had coined the term "secularism" in 1851.

In 1880, Brad ...

and Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

, with the goal of challenging Britain's obscenity laws. They were arrested (and later acquitted) but the publicity of their trial contributed to the formation, in 1877, of the Malthusian League

The Malthusian League was a British organisation which advocated the practice of contraception and the education of the public about the importance of family planning. It was established in 1877 and was dissolved in 1927. The organisation was secul ...

– the world's first birth control advocacy group – which sought to limit population growth to avoid Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book '' An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

's dire predictions of exponential population growth leading to worldwide poverty and famine. By 1930, similar societies had been established in nearly all European countries, and birth control began to find acceptance in most Western European countries, except Catholic Ireland, Spain, and France. As the birth control societies spread across Europe, so did birth control clinics. The first birth control clinic in the world was established in the Netherlands in 1882, run by the Netherlands' first female physician, Aletta Jacobs

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs (; 9 February 1854 – 10 August 1929) was a Dutch physician and women's suffrage activist. As the first woman officially to attend a Dutch university, she became one of the first female physicians in the Netherlands. I ...

. The first birth control clinic in England was established in 1921 by Marie Stopes

Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes (15 October 1880 – 2 October 1958) was a British author, palaeobotanist and campaigner for eugenics and women's rights. She made significant contributions to plant palaeontology and coal classification, ...

, in London.

Anti-contraception laws enacted

Contraception was legal in the United States throughout most of the 19th century, but in the 1870s a

Contraception was legal in the United States throughout most of the 19th century, but in the 1870s a social purity movement

The social purity movement was a late 19th-century social movement that sought to abolish prostitution and other sexual activities that were considered immoral according to Christian morality. The movement was active in English-speaking nations ...

grew in strength, aimed at outlawing vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or habit generally considered immoral, sinful, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character tra ...

in general, and prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

and obscenity in particular. Composed primarily of Protestant moral reformers and middle-class women, the Victorian-era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardi ...

campaign also attacked contraception, which was viewed as an immoral

Immorality is the violation of moral laws, norms or standards. It refers to an agent doing or thinking something they know or believe to be wrong. Immorality is normally applied to people or actions, or in a broader sense, it can be applied to gr ...

practice that promoted prostitution and venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral se ...

. Anthony Comstock

Anthony Comstock (March 7, 1844 – September 21, 1915) was an anti-vice activist, United States Postal Inspector, and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), who was dedicated to upholding Christian morality. He o ...

, a postal inspector Postal inspector may refer to:

* The United States Postal Inspection Service

The United States Postal Inspection Service (USPIS), or the Postal Inspectors, is the law enforcement arm of the United States Postal Service. It supports and protect ...

and leader in the purity movement, successfully lobbied for the passage of the 1873 Comstock Act

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of ...

, a federal law prohibiting mailing of "any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

" as well as any form of contraceptive information. Many states also passed similar state laws (collectively known as the ''Comstock laws

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of ...

''), sometimes extending the federal law by outlawing the ''use'' of contraceptives, as well as their distribution. Comstock was proud of the fact that he was personally responsible for thousands of arrests and the destruction of hundreds of tons of books and pamphlets.

Comstock and his allies also took aim at the libertarians

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's enc ...

and utopians who comprised the free love movement

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern of ...

– an initiative to promote sexual freedom, equality for women, and abolition of marriage. The free love proponents were the only group to actively oppose the Comstock laws in the 19th century, setting the stage for the birth control movement.Engelman, p. 20.

The efforts of the free love movement were not successful and, at the beginning of the 20th century, federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

and state government

A state government is the government that controls a subdivision of a country in a federal form of government, which shares political power with the federal or national government. A state government may have some level of political autonomy, or ...

s began to enforce the Comstock laws more rigorously. In response, contraception went underground, but it was not extinguished. The number of publications on the topic dwindled, and advertisements, if they were found at all, used euphemisms such as "marital aids" or "hygienic devices". Drug stores continued to sell condoms as "rubber goods" and cervical cap

The cervical cap is a form of barrier contraception. A cervical cap fits over the cervix and blocks sperm from entering the uterus through the external orifice of the uterus, called the ''os''.

Terminology

The term ''cervical cap'' has been ...

s as "womb supporters".

Beginning (1914–1916)

Free speech movement

At the turn of the century, an energetic movement arose, centered inGreenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, that sought to overturn bans on free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been ...

. Supported by radicals, feminists, anarchists, and atheists such as Ezra Heywood

Ezra Hervey Heywood (; September 29, 1829 – May 22, 1893) was an American individualist anarchist, slavery abolitionist, and advocate of equal rights for women.

Philosophy

Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of ...

, Moses Harman

Moses Harman (October 12, 1830January 30, 1910) was an American schoolteacher and publisher notable for his staunch support for women's rights. He was prosecuted under the Comstock Law for content published in his anarchist periodical ''Lucifer ...

, D. M. Bennett

DeRobigne Mortimer Bennett (December 23, 1818 – December 6, 1882), best known as D. M. Bennett, was the founder and publisher of ''Truth Seeker'', a radical freethought and reform American periodical.

Biography

Shaker Life

Derobigne M. Ben ...

, and Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, these activists regularly battled anti-obscenity laws and, later, the government's effort to suppress speech critical of involvement in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Prior to 1914, the free speech movement focused on politics, and rarely addressed contraception.

Goldman's circle of radicals, socialists, and bohemians was joined in 1912 by a nurse, Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

, whose mother had been through 18 pregnancies in 22 years, and died at age 50 of tuberculosis and cervical cancer. In 1913, Sanger worked in New York's Lower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally an im ...

, often with poor women who were suffering due to frequent childbirth and self-induced abortion

A self-induced abortion (also called a self-managed abortion, or sometimes a self-induced miscarriage) is an abortion performed by the pregnant woman herself, or with the help of other, non-medical assistance. Although the term includes abortion ...

s. After one particularly tragic medical case, Sanger wrote: "I threw my nursing bag in the corner and announced ... that I would never take another case until I had made it possible for working women in America to have the knowledge to control birth." Sanger visited public libraries, searching for information on contraception, but nothing was available. She became outraged that working-class women could not obtain contraception, yet upper-class women who had access to private physicians could.

Under the influence of Goldman and the Free Speech League, Sanger became determined to challenge the Comstock laws that outlawed the dissemination of contraceptive information.McCann (2010), pp. 750–751. With that goal in mind, in 1914 she launched ''The Woman Rebel'', an eight-page monthly newsletter which promoted contraception using the slogan "No Gods, No Masters", and proclaimed that each woman should be "the absolute mistress of her own body." Sanger coined the term ''birth control'', which first appeared in the pages of ''Rebel'', as a more candid alternative to euphemisms such as ''family limitation''.

Sanger's goal of challenging the law was fulfilled when she was indicted in August 1914, but the prosecutors focused their attention on articles Sanger had written on assassination and marriage, rather than contraception. Afraid that she might be sent to prison without an opportunity to argue for birth control in court, she fled to England to escape arrest.

While Sanger was in Europe, her husband continued her work, which led to his arrest after he distributed a copy of a birth control pamphlet to an undercover postal worker. The arrest and his 30-day jail sentence prompted several mainstream publications, including ''

Under the influence of Goldman and the Free Speech League, Sanger became determined to challenge the Comstock laws that outlawed the dissemination of contraceptive information.McCann (2010), pp. 750–751. With that goal in mind, in 1914 she launched ''The Woman Rebel'', an eight-page monthly newsletter which promoted contraception using the slogan "No Gods, No Masters", and proclaimed that each woman should be "the absolute mistress of her own body." Sanger coined the term ''birth control'', which first appeared in the pages of ''Rebel'', as a more candid alternative to euphemisms such as ''family limitation''.

Sanger's goal of challenging the law was fulfilled when she was indicted in August 1914, but the prosecutors focused their attention on articles Sanger had written on assassination and marriage, rather than contraception. Afraid that she might be sent to prison without an opportunity to argue for birth control in court, she fled to England to escape arrest.

While Sanger was in Europe, her husband continued her work, which led to his arrest after he distributed a copy of a birth control pamphlet to an undercover postal worker. The arrest and his 30-day jail sentence prompted several mainstream publications, including ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' and the ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'', to publish articles about the birth control controversy. Emma Goldman and Ben Reitman __NOTOC__

Ben Lewis Reitman M.D. (1879–1943) was an American anarchist and physician to the poor ("the hobo doctor"). He is best remembered today as one of radical Emma Goldman's lovers.

Reitman was a flamboyant, eccentric character. Emma Goldm ...

toured the country, speaking in support of the Sangers, and distributing copies of Sanger's pamphlet ''Family Limitation''. Sanger's exile and her husband's arrest propelled the birth control movement into the forefront of American news.

Early birth control organizations

In the spring of 1915 supporters of the Sangers – led byMary Dennett

Mary Coffin Ware Dennett (April 4, 1872 – July 25, 1947) was an American women's rights activist, pacifist, homeopathic advocate, and pioneer in the areas of birth control, sex education, and women's suffrage. She co-founded the National ...

– formed the National Birth Control League (NBCL), which was the first American birth control organization. Throughout 1915, smaller regional organizations were formed in San Francisco, Portland, Oregon, Seattle, and Los Angeles.

Sanger returned to the United States in October 1915. She planned to open a birth control clinic modeled on the world's first such clinic, which she had visited in Amsterdam. She first had to fight the charges outstanding against her. Noted attorney Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

offered to defend Sanger free of charge but, bowing to public pressure, the government dropped the charges early in 1916. No longer under the threat of jail, Sanger embarked on a successful cross-country speaking tour, which catapulted her into the leadership of the U.S. birth control movement.Engelman, p. 64. Other leading figures, such as William J. Robinson and Mary Dennett, chose to work in the background, or turned their attention to other causes. Later in 1916, Sanger traveled to Boston to lend her support to the Massachusetts Birth Control League and to jailed birth control activist Van Kleeck Allison.

First birth control clinic

During Sanger's 1916 speaking tour, she promoted birth control clinics based on the Dutch model she had observed during her 1914 trip to Europe. Although she inspired many local communities to create birth control leagues, no clinics were established. Sanger therefore resolved to create a birth control clinic in New York that would provide free contraceptive services to women. New York state law prohibited the distribution of contraceptives or even contraceptive information, but Sanger hoped to exploit a provision in the law which permitted doctors to prescribe contraceptives for the prevention of disease. On October 16, 1916, she, partnering with

During Sanger's 1916 speaking tour, she promoted birth control clinics based on the Dutch model she had observed during her 1914 trip to Europe. Although she inspired many local communities to create birth control leagues, no clinics were established. Sanger therefore resolved to create a birth control clinic in New York that would provide free contraceptive services to women. New York state law prohibited the distribution of contraceptives or even contraceptive information, but Sanger hoped to exploit a provision in the law which permitted doctors to prescribe contraceptives for the prevention of disease. On October 16, 1916, she, partnering with Fania Mindell

Fania Esiah Mindell (December 15, 1894July 18, 1969) was an American feminist, activist, and theater artist.

__TOC__

Life and career

Mindell was born in Minsk, Russia on December 15, 1894. She emigrated to Brooklyn, New York in 1906 with ...

and Ethel Byrne

Ethel Byrne ( Higgins; 18831955) was an American Progressive Era radical feminist. She was the younger sister of birth control activist Margaret Sanger, and assisted her in this work.

Background

Ethel and Margaret were two out of eleven children ...

, opened the Brownsville clinic in Brooklyn. The clinic was an immediate success, with over 100 women visiting on the first day. A few days after opening, an undercover policewoman purchased a cervical cap

The cervical cap is a form of barrier contraception. A cervical cap fits over the cervix and blocks sperm from entering the uterus through the external orifice of the uterus, called the ''os''.

Terminology

The term ''cervical cap'' has been ...

at the clinic, and Sanger was arrested. Refusing to walk, Sanger and a co-worker were dragged out of the clinic by police officers. The clinic was shut down, and it was not until 1923 that another birth control clinic was opened in the United States.

Sanger's trial began in January 1917. She was supported by a large number of wealthy and influential women who came together to form the Committee of One Hundred, which was devoted to raising funds for Sanger and the NBCL. The committee also started publishing the monthly journal ''Birth Control Review'', and established a network of connections to powerful politicians, activists, and press figures. Despite the strong support, Sanger was convicted; the judge offered a lenient sentence if she promised not to break the law again, but Sanger replied "I cannot respect the law as it exists today."Cox, p. 65.Engelman, p. 91. She served a sentence of 30 days in jail. In protest to her arrest as well, Byrne was sentenced to 30 days in jail at Blackwell's Island Prison and responded to her situation with a hunger strike protest. With no signs of ending her demonstration anytime soon, Byrne was force fed by prison guards. Weakened and ill, Byrne refused to end her hunger strike at the cost of securing early release from prison. However, Sanger accepted the plea bargain on her sister's behalf, agreeing that Byrne would be released early from prison if she ended her birth control activism. Horrified, Byrne's relationship quickly eroded with her sister and, both forcefully and willingly, she left the birth control movement. Due to the drama of Byrne's demonstration, the birth control movement became a headline news story in which the organization's purpose was distributed across the country. Other activists were also pushing for progress. Emma Goldman was arrested in 1916 for circulating birth control information, and

Abraham Jacobi

Abraham Jacobi (6 May 1830 – 10 July 1919) was a German physician and pioneer of pediatrics. He was a key figure in the movement to improve child healthcare and welfare in the United States and opened the first children's clinic in the country. ...

unsuccessfully tried to persuade the New York medical community to push for a change in law to permit physicians to dispense contraceptive information.

Mainstream acceptance (1917–1923)

The publicity from Sanger's trial and Byrne's hunger strike generated immense enthusiasm for the cause, and by the end of 1917 there were over 30 birth control organizations in the United States. Sanger was always astute about public relations, and she seized on the publicity of the trial to advance her causes. After her trial, she emerged as the movement's most visible leader. Other leaders, such as William J. Robinson, Mary Dennett, and

The publicity from Sanger's trial and Byrne's hunger strike generated immense enthusiasm for the cause, and by the end of 1917 there were over 30 birth control organizations in the United States. Sanger was always astute about public relations, and she seized on the publicity of the trial to advance her causes. After her trial, she emerged as the movement's most visible leader. Other leaders, such as William J. Robinson, Mary Dennett, and Blanche Ames Ames

Blanche Ames Ames (February 18, 1878 – March 2, 1969) was an American artist, political activist, inventor, writer, and prominent supporter of women's suffrage and birth control.

Personal life

Born Blanche Ames in Lowell, Massachusetts, Am ...

, could not match Sanger's charisma, charm and fervor.

The movement was evolving from radical, working-class roots into a campaign backed by society women and liberal professionals. Sanger and her fellow advocates began to tone down their radical rhetoric and instead emphasized the socioeconomic benefits of birth control, a policy which led to increasing acceptance by mainstream Americans. Media coverage increased, and several silent motion pictures produced in the 1910s featured birth control as a theme (including ''Birth Control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

'', produced by Sanger and starring herself).

Opposition to birth control remained strong: state legislatures refused to legalize contraception or the distribution of contraceptive information; religious leaders spoke out, attacking women who would choose "ease and fashion" over motherhood; and eugenicist

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

s were worried that birth control would exacerbate the birth rate differential between "old stock" white Americans and "coloreds" or immigrants.

Sanger formed the New York Woman's Publishing Company (NYWPC) in 1918 and, under its auspices, became the publisher for the ''Birth Control Review''. British suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

activist Kitty Marion

Kitty Marion 12 March 1871 – 9 October 1944) was born Katherina Maria Schäfer in Germany. She emigrated to London in 1886 when she was fifteen, and she grew to minor prominence when she sang in music halls throughout the United Kingdom during ...

, standing on New York street corners, sold the ''Review'' at 20 cents per copy, enduring death threats, heckling, spitting, physical abuse, and police harassment. Over the course of the following ten years, Marion was arrested nine times for her birth control advocacy.

Legal victory

Sanger appealed her 1917 conviction and won a mixed victory in 1918 in a unanimous decision by theNew York Court of Appeals

The New York Court of Appeals is the highest court in the Unified Court System of the State of New York. The Court of Appeals consists of seven judges: the Chief Judge and six Associate Judges who are appointed by the Governor and confirmed by t ...

written by Judge Frederick E. Crane

Frederick Evan Crane (March 2, 1869 in Brooklyn, Kings County, New York – November 21, 1947 in Garden City, New York, Garden City, Nassau County, New York) was an American lawyer and politician from New York (state), New York. He was Chief Judge ...

. The court's opinion upheld her conviction, but indicated that the courts would be willing to permit contraception if prescribed by doctors. This decision was only applicable within New York, where it opened the door for birth control clinics, under physician supervision, to be established. Sanger herself did not immediately take advantage of the opportunity, wrongly expecting that the medical profession would lead the way; instead she focused on writing and lecturing.

World War I and condoms

The birth control movement received an unexpected boost duringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, as a result of a crisis the U.S. military experienced when many of its soldiers were diagnosed with syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

or gonorrhea

Gonorrhea, colloquially known as the clap, is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium '' Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. Infection may involve the genitals, mouth, or rectum. Infected men may experience pain or burning with ...

. The military undertook an extensive education campaign, focusing on abstinence, but also offering some contraceptive guidance. The military, under pressure from purity advocates, did not distribute condoms, or even endorse their use, making the U.S. the only military force in World War I that did not supply condoms to its troops. When U.S. soldiers were in Europe, they found rubber condoms readily available, and when they returned to America, they continued to use condoms as their preferred method of birth control.

The military's anti-venereal disease campaign marked a major turning point for the movement: it was the first time a government institution had engaged in a sustained, public discussion of sexual matters. The government's public discourse changed sex from a secret topic into a legitimate topic of scientific research, and it transformed contraception from an issue of morals to an issue of public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

.

In 1917, advocate Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

was arrested for protesting World War I and American military conscription. Goldman's commitment to free speech on topics such as socialism, anarchism, birth control, labor/union rights, and free love eventually cost her American citizenship and the right to live in the United States. Due to her commitment to socialist welfare and anti-capitalism, Goldman was associated with communism which led to her expulsion from the country during the First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during History of the United States (1918–1945), the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Far-left politics, far-left movements, including Bolshevik, Bolshevism and ...

. While World War I led to a breakthrough on American acceptance of birth control relating to public health, anti-communist WWI propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

sacrificed one of the birth control movement's most dedicated members.

Legislative efforts

While an important birth control activist and leader, Mary Dennett advocated for a wide variety of organizations. Starting as a field secretary for the Massachusetts Women's Suffrage Association, she worked her way up to win an elected seat as a corresponding secretary for the National American Women's Suffrage Association. Dennett headed the literary department, undertaking assignments such as distributing pamphlets and leaflets. Following disillusionment with the NAWSA's organizational structure, Dennett, as described above, helped found the National Birth Control League. The NBCL took a strong stance against militant protest strategies and instead focused attention on legislation changes at both the state and federal level. During World War I, Mary Dennett focused her efforts on the peace movement, but she returned to the birth control movement in 1918. She continued to lead the NBCL, and collaborated with Sanger's NYWPC. In 1919, Dennett published a widely distributed educational pamphlet, ''The Sex Side of Life'', which treated sex as a natural and enjoyable act. However, in the same year, frustrated with the NBCL's chronic lack of funding, Dennett broke away and formed theVoluntary Parenthood League The Voluntary Parenthood League (VPL) was an organization that advocated for contraception during the birth control movement in the United States. The VPL was founded in 1919 by Mary Dennett. The VPL was a rival organization to Margaret Sanger' ...

(VPL). Both Dennett and Sanger proposed legislative changes that would legalize birth control, but they took different approaches: Sanger endorsed contraception but only under a physician's supervision; Dennett pushed for unrestricted access to contraception.McCann (1994) pp. 69–70.Engelman, pp. 113–115. Sanger, a proponent of diaphragms, was concerned that unrestricted access would result in ill-fitting diaphragms and would lead to medical

quackery

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of fraudulent or ignorant medical practices. A quack is a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, ...

. Dennett was concerned that requiring women to get prescriptions from physicians would prevent poor women from receiving contraception, and she was concerned about a shortage of physicians trained in birth control. Both legislative initiatives failed, partly because some legislators felt that fear of pregnancy was the only thing that kept women chaste. In the early 1920s, Sanger's leadership position in the movement solidified because she gave frequent public lectures, and because she took steps to exclude Dennett from meetings and events.

American Birth Control League

Although Sanger was busy publishing the ''Birth Control Review'' during 1919 and 1920, she was not formally affiliated with either of the major birth control organizations (NBCL or VPL) during that time. In 1921 she became convinced that she needed to associate with a formal body to earn the support of professional societies and the scientific community. Rather than join an existing organization, she considered creating a new one. As a first step, she organized the First American Birth Control Conference, held in November 1921 in New York City. On the final night of the conference, as Sanger prepared to give a speech in the crowded Town Hall theater, police raided the meeting and arrested her for disorderly conduct. From the stage she shouted: "we have a right to hold his meetingunder the Constitution ... let them club us if they want to." She was soon released.Engelman, pp. 124–125. The following day it was revealed thatPatrick Joseph Hayes

Patrick Joseph Hayes (November 20, 1867 – September 4, 1938) was an American cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Archbishop of New York from 1919 until his death, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1924.

Early life and ...

, the Archbishop of New York

The Archbishop of New York is the head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, who is responsible for looking after its spiritual and administrative needs. As the archdiocese is the metropolitan bishop, metropolitan see of the ecclesiastic ...

, had pressured the police to shut down the meeting. The Town Hall raid was a turning point for the movement: opposition from the government and medical community faded, and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

emerged as its most vocal opponent. After the conference, Sanger and her supporters established the American Birth Control League

The American Birth Control League (ABCL) was founded by Margaret Sanger in 1921 at the First American Birth Control Conference in New York City. The organization promoted the founding of birth control clinics and encouraged women to control their ...

(ABCL).

Second birth control clinic

Four years after the New York Court of Appeals opened the doors for physicians to prescribe contraceptives, Sanger opened a second birth control clinic, which she staffed with physicians to make it legal under that court ruling (the first clinic had employed nurses). This second clinic, theClinical Research Bureau

The Clinical Research Bureau was the first legal birth control clinic in the United States, and quickly grew into the leading contraceptive research center in the world. The CRB operated under numerous names and parent organizations from 1923 to 19 ...

(CRB), opened on January 2, 1923. To avoid police harassment the clinic's existence was not publicized, its primary mission was stated to be conducting scientific research, and it only provided services to married women. The existence of the clinic was finally announced to the public in December 1923, but this time there were no arrests or controversy. This convinced activists that, after ten years of struggle, birth control had finally become widely accepted in the United States.Engelman, p. 139. The CRB was the first legal birth control clinic in the United States, and quickly grew into the world's leading contraceptive research center.

Progress and setbacks (1920s–1940s)

Widespread acceptance

Following the successful opening of the CRB in 1923, public discussion of contraception became more commonplace, and the term "birth control" became firmly established in the nation's vernacular. Of the hundreds of references to birth control in magazines and newspapers of the 1920s, more than two-thirds were favorable.Engelman, p. 142. The availability of contraception signaled the end of the stricter morality of the

Following the successful opening of the CRB in 1923, public discussion of contraception became more commonplace, and the term "birth control" became firmly established in the nation's vernacular. Of the hundreds of references to birth control in magazines and newspapers of the 1920s, more than two-thirds were favorable.Engelman, p. 142. The availability of contraception signaled the end of the stricter morality of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, and ushered in the emergence of a more sexually permissive society. Other factors that contributed to the new sexual norms included increased mobility brought by the automobile, anonymous urban lifestyles, and post-war euphoria. Sociologists who surveyed women in Muncie, Indiana in 1925 found that all the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

women approved of birth control, and more than 80 percent of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

women approved. The birth rate in America declined 20 percent between 1920 and 1930, primarily due to increased use of birth control.

Opposition

Although clinics became more common in the late 1920s, the movement still faced significant challenges: Large sectors of the medical community were still resistant to birth control; birth control advocates wereblacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

ed by the radio industry; and state and federal laws – though generally not enforced – still outlawed contraception.

The most significant opponent to birth control was the Catholic Church, which mobilized opposition in many venues during the 1920s. Catholics persuaded the Syracuse city council to ban Sanger from giving a speech in 1924; the National Catholic Welfare Conference The National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC) was the annual meeting of the American Catholic hierarchy and its standing secretariat; it was established in 1919 as the successor to the emergency organization, the National Catholic War Council.

It co ...

lobbied against birth control; the Knights of Columbus

The Knights of Columbus (K of C) is a global Catholic fraternal service order founded by Michael J. McGivney on March 29, 1882. Membership is limited to practicing Catholic men. It is led by Patrick E. Kelly, the order's 14th Supreme Knight. ...

boycotted hotels that hosted birth control events; the Catholic police commissioner of Albany prevented Sanger from speaking there; the Catholic mayor of Boston, James Curley, blocked Sanger from speaking in public; and several newsreel

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, informa ...

companies, succumbing to pressure from Catholics, refused to cover stories related to birth control. The ABCL turned some of the boycotted speaking events to their advantage by inviting the press, and the resultant news coverage often generated public sympathy for their cause. However, Catholic lobbying was particularly effective in the legislative arena, where their arguments – that contraception was unnatural, harmful, and indecent – impeded several initiatives, including an attempt in 1924 by Mary Dennett to overturn federal anti-contraception laws.

Dozens of birth control clinics opened across the United States during the 1920s, but not without incident. In 1929, New York police raided a clinic in New York and arrested two doctors and three nurses for distributing contraceptive information that was unrelated to the prevention of disease. The ABCL achieved a major victory in the trial, when the judge ruled that use of contraceptives to space births farther apart was a legitimate medical treatment that benefited the health of the mother. The trial, in which many important physicians served as witnesses for the defense, helped to unite the physicians with the birth control advocates.

Eugenics and race

Before the advent of the birth control movement,

Before the advent of the birth control movement, eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

had become very popular in Europe and the U.S., and the subject was widely discussed in articles, movies, and lectures. Eugenicists had mixed feelings about birth control: they worried that it would exacerbate the birth rate differential between "superior" and "inferior" races, but they also recognized its value as a tool to "racial betterment". Eugenics buttressed the birth control movement's aims by correlating excessive births with increased poverty, crime and disease. Sanger published two books in the early 1920s that endorsed eugenics: ''Woman and the New Race'' and ''The Pivot of Civilization''. Sanger and other advocates endorsed ''negative eugenics'' (discouraging procreation of "inferior" persons), but did not advocate euthanasia or ''positive eugenics'' (encouraging procreation of "superior" persons). However, many eugenicists refused to support the birth control movement because of Sanger's insistence that a woman's primary duty was to herself, not to the state.

Like many white Americans in the U.S. in the 1930s, some leaders of the birth control movement believed that lighter-skinned races were superior to darker-skinned races. They assumed that African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s were intellectually backward, would be relatively incompetent in managing their own health, and would require special supervision from whites. The dominance of whites in the movement's leadership and medical staff resulted in accusations of racism from blacks and suspicions that "race suicide" would be a consequence of large scale adoption of birth control. These suspicions were misinterpreted by some of the white birth control advocates as lack of interest in contraception.

In spite of these suspicions, many African-American leaders supported efforts to supply birth control to the African-American community. In 1929, James H. Hubert, a black social worker and leader of New York's

In spite of these suspicions, many African-American leaders supported efforts to supply birth control to the African-American community. In 1929, James H. Hubert, a black social worker and leader of New York's Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

, asked Sanger to open a clinic in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

. Sanger secured funding from the Julius Rosenwald Fund

The Rosenwald Fund (also known as the Rosenwald Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, and the Julius Rosenwald Foundation) was established in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald and his family for "the well-being of mankind." Rosenwald became part-owner of S ...

and opened the clinic, staffed with African-American doctors, in 1930. The clinic was guided by a 15-member advisory board consisting of African-American doctors, nurses, clergy, journalists, and social workers.Hajo, p. 85. It was publicized in the African-American press and African-American churches, and received the approval of W. E. B. Du Bois, co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP). In the early 1940s, the Birth Control Federation of America

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (PPFA), or simply Planned Parenthood, is a nonprofit organization that provides Reproductive health, reproductive health care in the United States and globally. It is a tax-exempt corporation ...

(BCFA) initiated a program called the Negro Project, managed by its Division of Negro Service (DNS). As with the Harlem clinic, the primary aim of the DNS and its programs was to improve maternal and infant health. Based on her work at the Harlem clinic, Sanger suggested to the DNS that African Americans were more likely to take advice from a doctor of their own race, but other leaders prevailed and insisted that whites be employed in the outreach efforts. The discriminatory actions and statements by the movement's leaders during the 1920s and 1930s have led to continuing allegations that the movement was racist.

Expanding availability

Two important legal decisions in the 1930s helped increase the accessibility of contraceptives. In 1930, two condom manufacturers sued each other in the ''Youngs Rubber'' case, and the judge ruled that contraceptive manufacturing was a legitimate business enterprise. He went further, and declared that the federal law prohibiting the mailing of condoms was not legally sound. Sanger precipitated a second legal breakthrough when she ordered a diaphragm from Japan in 1932, hoping to provoke a decisive battle in the courts. The diaphragm was confiscated by the U.S. government, and Sanger's subsequent legal challenge led to the 1936 '' One Package'' legal ruling by Judge Augustus Hand. His decision overturned an important provision of the anti-contraception laws that prohibited physicians from obtaining contraceptives. This court victory motivated the

Two important legal decisions in the 1930s helped increase the accessibility of contraceptives. In 1930, two condom manufacturers sued each other in the ''Youngs Rubber'' case, and the judge ruled that contraceptive manufacturing was a legitimate business enterprise. He went further, and declared that the federal law prohibiting the mailing of condoms was not legally sound. Sanger precipitated a second legal breakthrough when she ordered a diaphragm from Japan in 1932, hoping to provoke a decisive battle in the courts. The diaphragm was confiscated by the U.S. government, and Sanger's subsequent legal challenge led to the 1936 '' One Package'' legal ruling by Judge Augustus Hand. His decision overturned an important provision of the anti-contraception laws that prohibited physicians from obtaining contraceptives. This court victory motivated the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's state ...

in 1937 to finally adopt contraception as a normal medical service and a core component of medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

curricula

In education, a curriculum (; : curricula or curriculums) is broadly defined as the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view ...

. However, the medical community was slow to accept this new responsibility, and women continued to rely on unsafe and ineffective contraceptive advice from ill-informed sources until the 1960s.

By 1938, over 400 contraceptive manufacturers were in business, over 600 brands of female contraceptives were available, and industry revenues exceeded $250 million per year. Condoms were sold in vending machine

A vending machine is an automated machine that provides items such as snacks, beverages, cigarettes, and lottery tickets to consumers after cash, a credit card, or other forms of payment are inserted into the machine or otherwise made. The fir ...

s in some public restrooms, and men spent twice as much on condoms as on shaving. Although condoms had become commonplace in the 1930s, feminists in the movement felt that birth control should be the woman's prerogative, and they continued to push for development of a contraceptive that was under the woman's control, a campaign which ultimately led to the birth control pill