Birlinn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The birlinn ( gd, bìrlinn) or West Highland galley was a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oar, used extensively in the

The birlinn ( gd, bìrlinn) or West Highland galley was a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oar, used extensively in the

The hull bore a general resemblance to the Norse pattern, but stem and stern may have been more steeply pitched (though allowance must be paid for distortion in representation). Surviving images show a rudder. Nineteenth-century boat-building practices in the Highlands are likely to have applied also to the birlinn: examples are the use of dried moss, steeped in

The hull bore a general resemblance to the Norse pattern, but stem and stern may have been more steeply pitched (though allowance must be paid for distortion in representation). Surviving images show a rudder. Nineteenth-century boat-building practices in the Highlands are likely to have applied also to the birlinn: examples are the use of dried moss, steeped in

A reproduction of a 16-oar Highland galley, the ''Aileach'', was built in 1991 at Moville in

A reproduction of a 16-oar Highland galley, the ''Aileach'', was built in 1991 at Moville in

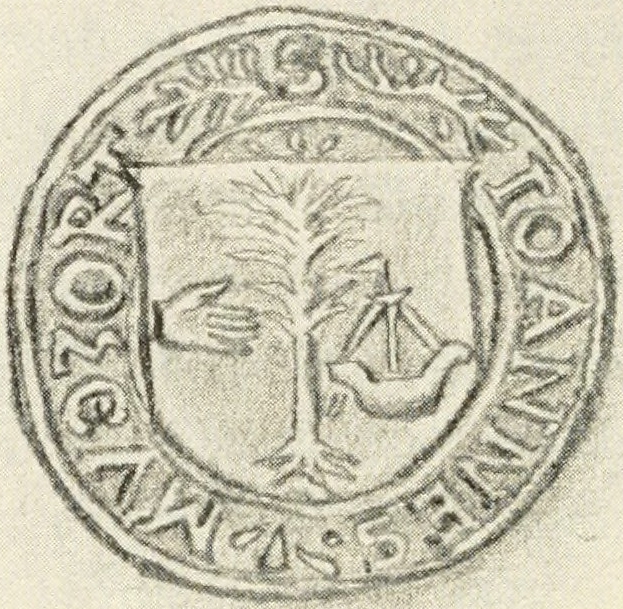

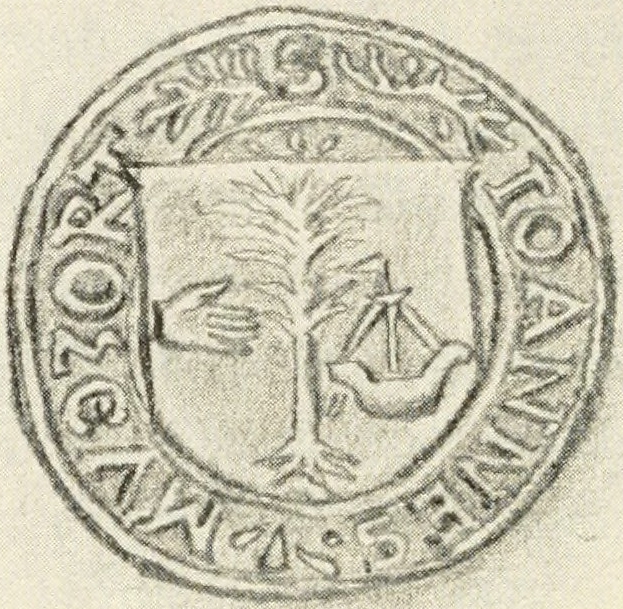

There is some evidence that by the end of the sixteenth century new influences were affecting birlinn design. A carving made at Arasaig in 1641 shows a vessel with a lowered stem and stern. An English map of north-east Ireland made no later than 1603 shows "fleetes of the Redshanks ighlandersof Cantyre" with vessels one-masted as before but with a square sail mounted on a sloping yard arm and a small cabin at the stern projecting backwards. Two Clanranald seals attached to documents dated 1572 show a birlinn with raised decks at stem and stern, a motif repeated in later heraldic devices. If such changes occurred, they would reflect influences from the south-east and ultimately from the Mediterranean. The supporting evidence has been criticised for being slight and unconvincing,Caldwell, p. 146 but there is pictorial evidence for similar developments in the Irish galley.

There is some evidence that by the end of the sixteenth century new influences were affecting birlinn design. A carving made at Arasaig in 1641 shows a vessel with a lowered stem and stern. An English map of north-east Ireland made no later than 1603 shows "fleetes of the Redshanks ighlandersof Cantyre" with vessels one-masted as before but with a square sail mounted on a sloping yard arm and a small cabin at the stern projecting backwards. Two Clanranald seals attached to documents dated 1572 show a birlinn with raised decks at stem and stern, a motif repeated in later heraldic devices. If such changes occurred, they would reflect influences from the south-east and ultimately from the Mediterranean. The supporting evidence has been criticised for being slight and unconvincing,Caldwell, p. 146 but there is pictorial evidence for similar developments in the Irish galley.

GalGael

– using the Birlinn to rebuild community in Scotland

from Mallaig Heritage

Image of fifteenth-century engraved Birlinn, in Rodel Chapel, Harris

on Flickr {{Scandinavian Scotland Norse-Gaels Boat types Transport in Scotland Scandinavian Scotland Medieval ships Sailing ship types Human-powered watercraft Tall ships 14th-century ships

The birlinn ( gd, bìrlinn) or West Highland galley was a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oar, used extensively in the

The birlinn ( gd, bìrlinn) or West Highland galley was a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oar, used extensively in the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

and West Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland ...

of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

from the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

on. Variants of the name in English and Lowland Scots include "berlin" and "birling". The Gaelic term may derive from the Norse ''byrðingr'' (ship of boards), a type of cargo vessel. It has been suggested that a local design lineage might also be traceable to vessels similar to the Broighter-type boat (first century BC), equipped with oars and a square sail, without the need to assume a specific Viking design influence. It is uncertain, however, whether the Broighter model represents a wooden vessel or a skin-covered boat of the currach

A currach ( ) is a type of Irish boat with a wooden frame, over which animal skins or hides were once stretched, though now canvas is more usual. It is sometimes anglicised as "curragh".

The construction and design of the currach are unique ...

type. The majority of scholars emphasise the Viking influence on the birlinn.

The birlinn was clinker-built

Clinker built (also known as lapstrake) is a method of boat building where the edges of hull (watercraft), hull planks overlap each other. Where necessary in larger craft, shorter planks can be joined end to end, creating a longer strake or hull ...

and could be sailed or rowed. It had a single mast with a square sail. Smaller vessels of this type might have had as few as twelve oars, with the larger West Highland galley having as many as forty. For over four hundred years, down to the seventeenth century, the birlinn was the dominant vessel in the Hebrides.

In 1310, King Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventual ...

granted Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the ...

a reddendo or charter making him Lord of the Isle of Man in exchange for six birlinns of 26 oars. A 1615 report to the Scottish Privy Council made a distinction between galleys, having between 18 and 20 oars, and birlinns, with between 12 and 18 oars. There was no suggestion of structural differences. The report stated that there were three men per oar.

The birlinn appears in Scottish heraldry

Heraldry in Scotland, while broadly similar to that practised in England and elsewhere in western Europe, has its own distinctive features. Its heraldic executive is separate from that of the rest of the United Kingdom.

Executive

The Scottish he ...

as the "lymphad 200px

A lymphad or galley is a charge used primarily in Scottish heraldry. It is a single-masted ship propelled by oars. In addition to the mast and oars, the lymphad has three flags and a basket. The word comes from the Scottish Gaelic ''long fh ...

", from the Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

''long fhada''.

Use

In terms of design and function, there was considerable similarity between the local birlinn and the ships used by Norse incomers to the Isles. In an island environment ships were essential for the warfare which was endemic in the area, and local lords used the birlinn extensively from at least the thirteenth century. The strongest of the regional naval powers were theMacDonalds of Islay

Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg, also known as Clan Donald South, ''Clan Iain Mor, Clan MacDonald of Islay and Kintyre, MacDonalds of the Glens (Antrim)'' and sometimes referred to as ''MacDonnells'', is a Scottish clan and a branch of Clan Donald. T ...

.

The Lords of the Isles

The Lord of the Isles or King of the Isles

( gd, Triath nan Eilean or ) is a title of Scottish nobility with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It began with Somerled in the 12th century and thereafter the title w ...

of the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

maintained the largest fleet in the Hebrides. It is possible that vessels of the birlinn type were used in the 1156 sea battle in which Somerled, Lord of Argyll, the ancestor of the lords, firmly established himself in the Hebrides by confronting his brother-in-law, Godred Olafsson, King of the Isles.

In 1608 Andrew Stewart, Lord Ochiltree was sent by James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

to quell feuds in the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

. His orders included the destruction of shipping, named in his commissions as lymphad 200px

A lymphad or galley is a charge used primarily in Scottish heraldry. It is a single-masted ship propelled by oars. In addition to the mast and oars, the lymphad has three flags and a basket. The word comes from the Scottish Gaelic ''long fh ...

s, galleys, and birlinns belonging to rebellious subjects.

Though the surviving evidence has mostly to do with the birlinn in a naval context, there is independent evidence of mercantile activity for which such shipping would have been essential. There is some evidence for mercantile centres in Islay

Islay ( ; gd, Ìle, sco, Ila) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll just south west of Jura, Scotland, Jura and around north of the Northern Irish coast. The isl ...

, Gigha

Gigha (; gd, Giogha, italic=yes; sco, Gigha) or the Isle of Gigha (and formerly Gigha Island) is an island off the west coast of Kintyre in Scotland. The island forms part of Argyll and Bute and has a population of 163 people. The climate is m ...

, Kintyre

Kintyre ( gd, Cinn Tìre, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East and West Loch Tarbert in the north. The region immediately north ...

and Knapdale

Knapdale ( gd, Cnapadal, IPA: �kraʰpət̪əɫ̪ forms a rural district of Argyll and Bute in the Scottish Highlands, adjoining Kintyre to the south, and divided from the rest of Argyll to the north by the Crinan Canal. It includes two parishes, ...

, and in the fourteenth century there was constant trade between the Isles, Ireland and England under the patronage of local lords. It is possible that the resources of the Highlands and Islands were not sufficient to support both naval and trading types of ship, leaving the galley with both roles. The derivation of the word birlinn from the name of a Nordic cargo vessel is suggestive of that situation. Otherwise the chief uses of the birlinn would have been troop-carrying, fishing and cattle transport.

Construction and maintenance

In some ways the birlinn paralleled the more robust ocean-going craft of Norse design. Viking ships were double-ended, with akeel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

scarfed to stems fore and aft. A shell of thin planking (strake

On a vessel's hull, a strake is a longitudinal course of planking or plating which runs from the boat's stempost (at the bows) to the sternpost or transom (at the rear). The garboard strakes are the two immediately adjacent to the keel on ...

) was constructed on the basis of the keel, the planks being edge-joined and clenched with iron nails. Symmetrical ribs or frames were then lashed to the strakes or secured with trenail

A treenail, also trenail, trennel, or trunnel, is a wooden peg, pin, or dowel used to fasten pieces of wood together, especially in timber frames, covered bridges, wooden shipbuilding and boat building. It is driven into a hole bored through two ...

s. Over most of the ribs was laid a slender crossbeam and a thwart

A thwart is a part of an undecked boat that provides seats for the crew and structural rigidity for the hull. A thwart goes from one side of the hull to the other. There might be just one thwart in a small boat, or many in a larger boat, especial ...

. The mast was stepped amidships or nearly so, and oars, including a steering oar, were also used. The stem and stern post sometimes had carefully carved notches for plank ends, with knees securing the thwarts to the strakes and beams joining the heads of the frames.

The hull bore a general resemblance to the Norse pattern, but stem and stern may have been more steeply pitched (though allowance must be paid for distortion in representation). Surviving images show a rudder. Nineteenth-century boat-building practices in the Highlands are likely to have applied also to the birlinn: examples are the use of dried moss, steeped in

The hull bore a general resemblance to the Norse pattern, but stem and stern may have been more steeply pitched (though allowance must be paid for distortion in representation). Surviving images show a rudder. Nineteenth-century boat-building practices in the Highlands are likely to have applied also to the birlinn: examples are the use of dried moss, steeped in tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bit ...

, for caulking

Caulk or, less frequently, caulking is a material used to seal joints or seams against leakage in various structures and piping.

The oldest form of caulk consisted of fibrous materials driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards on w ...

, and the use of stocks in construction.

Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

was the wood favoured both in Western Scotland and in Scandinavia, being tough and resistant to decay. Other types of timber were less often used. It is likely that the Outer Isles of Western Scotland had always been short of timber, but birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

, oak and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

abounded in the Inner Isles and on the mainland. The abundance of timber at Lochaber

Lochaber ( ; gd, Loch Abar) is a name applied to a part of the Scottish Highlands. Historically, it was a provincial lordship consisting of the parishes of Kilmallie and Kilmonivaig, as they were before being reduced in extent by the creation ...

was proverbial: "''B'e sin fiodh a chur do Loch Abar''" ("Bringing wood to Lochaber") was said of any superfluous undertaking.

The tools used are likely to have included adze

An adze (; alternative spelling: adz) is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing ...

s, axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

s, augers and spoon bits, awls

Awl may refer to:

Tools

* Bradawl, a woodworking hand tool for making small holes

* Scratch awl, a woodworking layout and point-making tool used to scribe a line

* Stitching awl, a tool for piercing holes in a variety of materials such as leathe ...

, planes, draw knives and moulding irons, together with other tools typical of the Northern European carpenter's kit. As in traditional shipbuilding, generally, measurements were largely by eye.

The traditional practice of sheltering boats in bank-cuttings ("nausts") – small artificial harbour

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

s – was probably also employed with the birlinn. There is evidence in fortified sites of constructed harbours, boat-landings and sea-gates.

The influence of Norse shipbuilding techniques, though plausible, is conjectural, since to date no substantial remnants of a birlinn have been found. Traditional boat-building techniques and terms, however, may furnish a guide as to the vessel's construction.

Rigging and sails

Carved images of the birlinn from the sixteenth century and earlier show the typical rigging: braces,forestay

On a sailing vessel, a forestay, sometimes just called a stay, is a piece of standing rigging which keeps a mast from falling backwards. It is attached either at the very top of the mast, or in fractional rigs between about 1/8 and 1/4 from the t ...

and backstay

A backstay is a piece of standing rigging on a sailing vessel that runs from the mast to either its transom or rear quarter, counteracting the forestay and jib. It is an important sail trim control and has a direct effect on the shape of the main ...

, shrouds (fore and aft), halyard

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term ''halyard'' comes from the phrase "to haul yards". Halyards, like most other parts of the running rigging, were classically made of n ...

and a parrel (a movable loop used to secure a yard or gaff to a mast). There is a rudder with pintle

A pintle is a pin or bolt, usually inserted into a gudgeon, which is used as part of a pivot or hinge. Other applications include pintle and lunette ring for towing, and pintle pins securing casters in furniture.

Use

Pintle/gudgeon sets have ma ...

s on the leading edge, inserted into gudgeon

A gudgeon is a socket-like, cylindrical (i.e., ''female'') fitting attached to one component to enable a pivoting or hinging connection to a second component. The second component carries a pintle fitting, the male counterpart to the gudgeon, ...

s. It is possible that use was made of a wooden bowline or reaching spar (called a ''beitass A beitass, or a stretching pole, is a wooden spar used on Viking ships that was fitted into a pocket at the lower corner of the sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power t ...

'' by the Norse). This was used to push the luff of the sail out into the wind.

Traditional Highland practice was to make sails of tough, thick-threaded wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

, with ropes being made of moss-fir or heather. Medieval sails, in the Highlands as elsewhere, are shown as being sewn out of many small squares, and there is possible evidence of reef points.

''Aileach'': a reconstruction

A reproduction of a 16-oar Highland galley, the ''Aileach'', was built in 1991 at Moville in

A reproduction of a 16-oar Highland galley, the ''Aileach'', was built in 1991 at Moville in Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

. It was based on representations of such vessels in West Highland sculpture. Despite the good seagoing performance of the vessel, its design has been described as misleading because of an over-reliance in the plan on cramped sculptural images. The vessel was designed with a high, almost vertical, stern and stem. It proved difficult to fit in more than one rower per oar and the thwarts were too close together. Less constricted images from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries show vessels which are longer and larger.

Ireland

The Irish ''long fhada'' seems, from contemporary sources, to have resembled its West Highland equivalent, though there is as yet no archaeological confirmation. The ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

'' record the use of fleets in an Irish context, often with a Scottish connection. In 1413 Tuathal Ó Máille, returning from Ulster to Connacht with seven ships, encountered a severe storm (''anfadh na mara'') which drove them northwards to Scotland: only one of the ships survived. In 1433 Macdonald of the Isles arrived in Ulster with a large fleet (''co c-cobhlach mór'') to assist the O'Neills in a war with the O'Donnells.

In Ireland oared vessels were employed extensively for warfare and piracy by the O'Malleys and the O'Flathertys, western lords whose base was in Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

. English officials found it necessary to counter them with similar vessels. The most famous of these local rulers was Grace O'Malley

Grace O'Malley ( – c. 1603), also known as Gráinne O'Malley ( ga, Gráinne Ní Mháille, ), was the head of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland, and the daughter of Eóghan Dubhdara Ó Máille.

In Irish folklore she is commonly k ...

, of whom Sir Richard Bingham

Sir Richard Bingham (1528 – 19 January 1599) was an English soldier and naval commander. He served under Queen Elizabeth I during the Tudor conquest of Ireland and was appointed governor of Connacht.

Early life and military career

Bingham ...

reported in 1591 that she had twenty vessels at her command. She, like her father, was engaged in extensive seaborne trade.

There was constant maritime traffic between Ireland and Scotland, and Highland mercenaries were commonly transported by birlinn to Ireland.Rixson, pp. 101–102

Naval technology

The birlinn, when rowed, was distinguished by its speed, and could often evade pursuers as a result. No cannon were mounted even in the later period: the birlinn was too lightly built and its freeboard was too low. It was highly suitable for raiding, however, and with experienced marksmen on board, could mount a formidable defence against small craft. Vessels of this type were at their most vulnerable when beached or when cornered by a heavier vessel carrying cannon.Possible changes in design

There is some evidence that by the end of the sixteenth century new influences were affecting birlinn design. A carving made at Arasaig in 1641 shows a vessel with a lowered stem and stern. An English map of north-east Ireland made no later than 1603 shows "fleetes of the Redshanks ighlandersof Cantyre" with vessels one-masted as before but with a square sail mounted on a sloping yard arm and a small cabin at the stern projecting backwards. Two Clanranald seals attached to documents dated 1572 show a birlinn with raised decks at stem and stern, a motif repeated in later heraldic devices. If such changes occurred, they would reflect influences from the south-east and ultimately from the Mediterranean. The supporting evidence has been criticised for being slight and unconvincing,Caldwell, p. 146 but there is pictorial evidence for similar developments in the Irish galley.

There is some evidence that by the end of the sixteenth century new influences were affecting birlinn design. A carving made at Arasaig in 1641 shows a vessel with a lowered stem and stern. An English map of north-east Ireland made no later than 1603 shows "fleetes of the Redshanks ighlandersof Cantyre" with vessels one-masted as before but with a square sail mounted on a sloping yard arm and a small cabin at the stern projecting backwards. Two Clanranald seals attached to documents dated 1572 show a birlinn with raised decks at stem and stern, a motif repeated in later heraldic devices. If such changes occurred, they would reflect influences from the south-east and ultimately from the Mediterranean. The supporting evidence has been criticised for being slight and unconvincing,Caldwell, p. 146 but there is pictorial evidence for similar developments in the Irish galley.

See also

* Irish galleyNotes

References

* Caldwell, David H. (2007), 'Having the right kit: West Highlanders fighting in Ireland' in ''The World of the Gallowglass: kings, warlords and warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600''. Duffy, Seán (ed.). Dublin: Four Courts Press. * * * Watson, J. Carmichael (ed.) (1934). ''Gaelic Songs of Mary MacLeod''. Blackie & Son LimiteFurther reading

* Macauley, John (1996), ''Birlinn – Longships of the Hebrides''. The White Horse Press.External links

GalGael

– using the Birlinn to rebuild community in Scotland

from Mallaig Heritage

Image of fifteenth-century engraved Birlinn, in Rodel Chapel, Harris

on Flickr {{Scandinavian Scotland Norse-Gaels Boat types Transport in Scotland Scandinavian Scotland Medieval ships Sailing ship types Human-powered watercraft Tall ships 14th-century ships